City churches are interesting, not just the history of the church, but also for the artifacts that London’s churches seem to accumulate. St Martin Ludgate, or to give the full name St Martin Within Ludgate is a church I have not visited for a while, so on a rather grey day I went for another look inside the church.

St Martin Ludgate is on the northern side of Ludgate Hill. I suspect that the church suffers from the fact that St Paul’s Cathedral is at the top of Ludgate Hill and the cathedral tends to attract the gaze, rather than the historic church along the side of the street.

The view looking down Ludgate Hill with the church and spire of St Martin Ludgate on the right:

St Martin is an old City church, with written evidence dating the church to the 12th century, however Geoffrey of Monmouth writing in the 12th century claims that the church was founded by the Welsh King Cadwallader in the 7th century. Given that this was 500 years before Geoffrey of Monmouth, I doubt very much whether this was based on any truth or factual record.

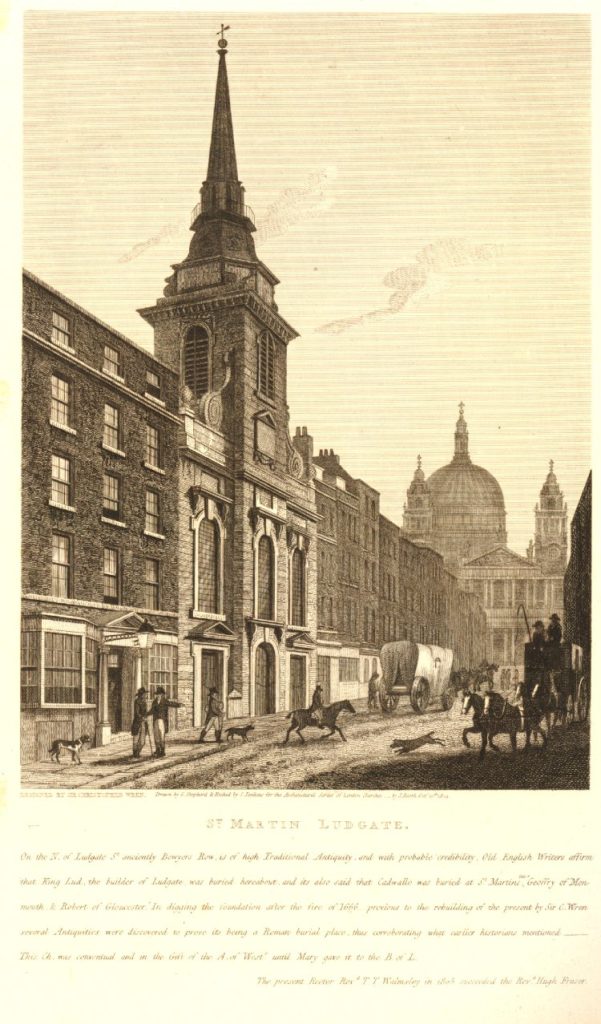

The claim was embellished in the text with the following print from 1814 which shows the tower and steeple of St Martin Ludgate standing clear from the surrounding houses. The author adds that Cadwallo was buried here. The text included evidence that the site was ancient as “several antiquities were discovered to prove it being a Roman burial-place”.

The location was certainly interesting, being adjacent to Lud Gate and the Roman Wall. Travelers from the west would have approached the City along what is now the Strand. Crossing over the River Fleet, then a short distance up the hill to the Lud Gate, with the location of St Martins just inside the wall on the left.

The current church dates from between 1677 and 1686 when it was rebuilt by Wren following the destruction of the previous church in the Great Fire of London, although there is a possibility that rather than Wren, it was Robert Hooke who was responsible for the church.

The original church was slightly clear of the Roman Wall, however the new church was moved slightly to the west and included the Roman Wall in the foundations of the church. Ludgate Hill was also widened at this time, so the new church was also set slightly further back

The spire of the church was designed to be a counterpoint to the dome of St Paul’s Cathedral.

Through the entrance to the church and there is a wide corridor running the width of the building before entering the church proper. This was an attempt to sound proof the church from the noise on Ludgate Hill which must have been one of the busier and noisier streets in the City.

Entering the church and we can see a typical Wren designed City church of the 17th century.

The organ loft above the font:

The font dates from 1673 and was a gift to the rebuilt church from one Thomas Morley.

Behind and to the right of the font is an information panel that confirms that this wall of the church was the original western limit of the Roman City, and below the floor and wall are the foundations of the original Roman Wall, along with remains of the later Medieval Wall.

The full name of the church St Martin within Ludgate indicates that the church was within the City walls.

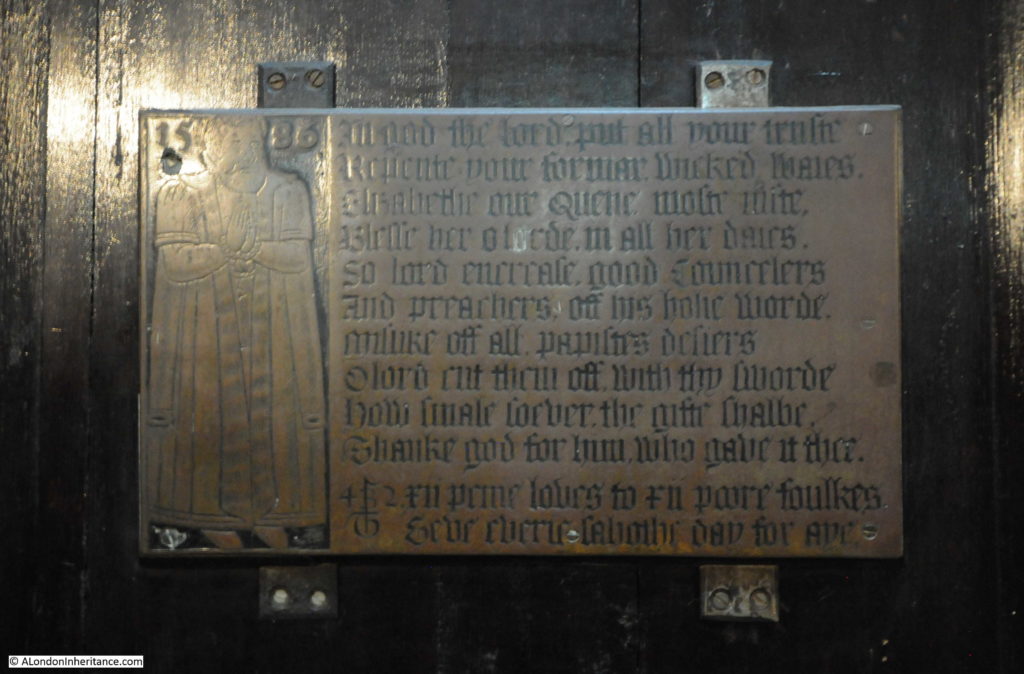

There is an interesting plaque in the church, which holds a hidden message in the text. A brass plaque, now in St Martin’s was originally in St Mary Magdalene’s on Old Fish Street. A serious fire severely damaged much of St Mary in 1886, and as a number of City churches were closing and being demolished under the Union of Benefices Act (an Act to reduce the number of City churches as the population of the City had decreased), the decision was taken not to rebuild St Mary and a number of artifacts were moved to St Martin Ludgate.

The plaque is shown in the following photo and dates from 1586.

The plaque records a charity set up by Elizabethan fish monger Thomas Berry, or Beri. He is seen on the left of the plaque, and to the right are ten lines of text, followed by two lines which describe the charity:

“XII Penie loaves, to XI poor foulkes. Gave every Sabbath Day for aye”

The plaque is dated 1586, and the charity was set up in his will of 1601 which left his property in Edward Street, Southwark to St Mary Magdalen, with the instruction that the rent should be used to fund the loaves. The recipients of the charity were not in London, but were in Walton-on-the-Hill (now a suburb of Liverpool), a village that Berry seems to have had some connection with. The charity included an additional sum of 50s a year to fund a dinner for all the married people and householders of the town of Bootle.

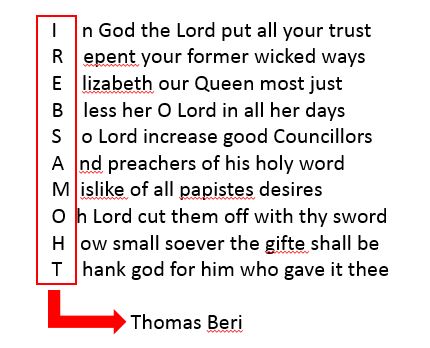

The interesting lines of text are above those which describe the charity. Thomas seems to have spelled his last name either Berry or Beri and these ten lines of anti-papist verse include his concealed name.

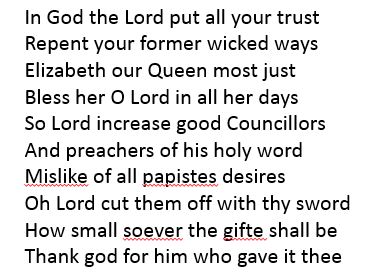

The ten lines are shown below (thankfully “If Stones Could Speak” by F. St Aubyn-Brisbane (1929) have the transcribed text as it was hard to read from the plaque):

If you take the first letter from each sentence and read from the last sentence, you get the name Tomas Beri.

The parish church in Walton-on-the-Hill had a similar brass plaque, however it was badly damaged when the church was destroyed in the Liverpool Blitz in May 1941. The Walton church was rebuilt after the war, and a replica plaque can now be seen.

Unlike the Walton church, St Martin Ludgate suffered the least damage of any City church during the last war, with only a single incendiary bomb damaging the roof.

A closer view of the font. The wall behind the font marks the limit of the original Roman City, and remains of the Roman Wall are below the wall of the church.

City churches tend to accumulate objects, not just from other City churches, but from across the world. For some reason, St Martin Ludgate has a large chandelier from the 18th century which was originally in St Vincent’s Cathedral in the West Indies.

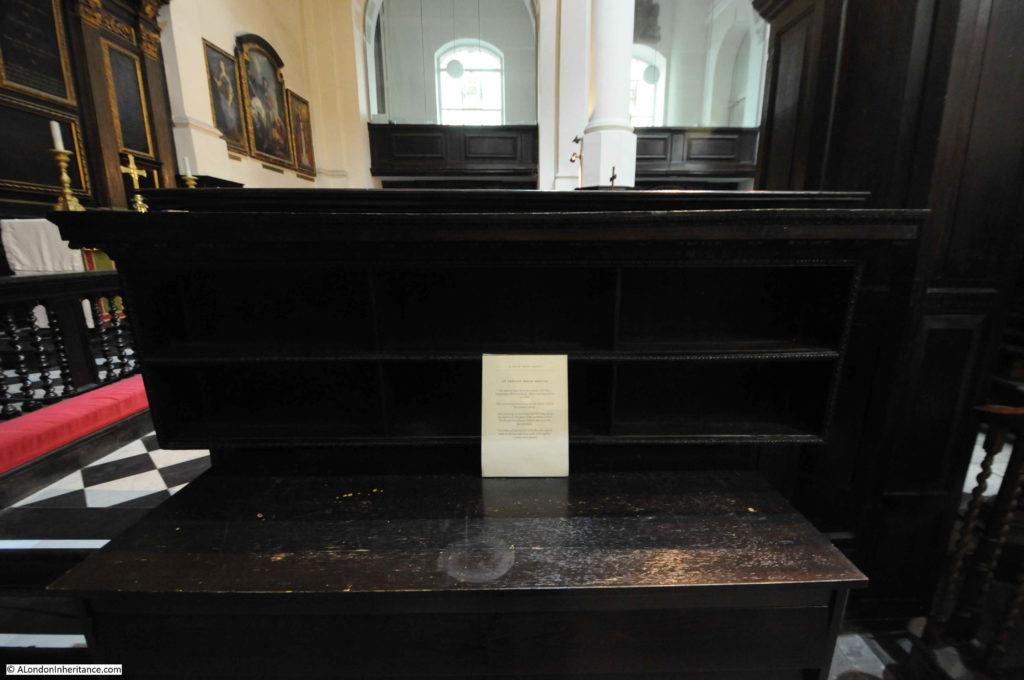

The chandelier is unusual as the majority of objects in the church appear to have come from St Mary Magdalen, including these bread shelves:

On display within the church is one of the bells from the post Great Fire rebuild. The bell dates from 1683 and was a “Gift of William Warne, Scrivener to the Parish of St Martin’s Ludgate”:

In a side room of the church is an interesting 17th century carved pelican:

The symbol of the pelican feeding its young is a very early Christian representation of Jesus. It comes from a pre-Christian legend that in times of famine, a mother pelican would pierce her breast, allowing her young to feed on her blood, thereby avoiding starvation.

Apart from the slender spire, there is nothing remarkable about the building of St Martin Ludgate, and the church is over shadowed by the much larger cathedral a bit further up Ludgate Hill.

The key though with City churches is that despite the ever-changing City, they are stable reference points, providing the same function for over 900 years.

St Martin Ludgate has the added bonus that the west wall of the church marks the western boundary of the original Roman city, and the Roman wall.

And whilst pondering the Roman city, we can also wonder why Thomas Beri decided to conceal his name in the plaque, or what game he was playing with the future back in 1586.

Many thanks for another very interesting story.

I love this church and I love Ludgate Hill as well, such a fine street. When I build my time machine (not long, I hope) I will hop back to London in the very early years of the 19th century and take a good look around at the place before the capitalists decided to descend and transform. That’s a great image from 1814.

One of the things that has always fascinated me about this church, is that unusually it’s not free standing like most churches, but part of the terrace of buildings, perhaps more like you might find in Italy or elsewhere.

Fascinating information as always

Once again a fascinating insight into a single building which I have visited a number of times on group excursions into London. Adjacent to the church is Ye Olde London public house, now run by Greene King. Descend to the basement level and exit into their “Beer Garden” where you will find a number of Gravestones which one must assume are directly associated with the church alongside.

Fascinating! Thank you especially for deciphering the Thomas Beri, and for the history of the Church’s relationship to the Roman wall.

Great article,thankyou. I visited St Martins some years ago and I remember a connection with Pennsylvania USA. Am I right in saying that William Penn was Christened here or were his parents married in St. Martins?

Beautiful church with a great history.

Joseph, his parents were indeed married in St Martin in 1643

Thank you for another fascinating insight.

I took a number of photos of the area in 2014, and several are of St Martin’s facade, including one that shows bit St Martin’s and St Paul’s. They’re here:

https://www.flickr.com/photos/irontongue/albums/72157645194063154

Lisa

Great pictures – your attention to detail is remarkable.

Thank you, Mike!

The most original & complete of the Wren churches in London. The pulpit dates from this time for example. The architect would ascend the spire of St. Martin Ludgate to view progress on St. Paul’s cathedral.

Very good. This church is one of the handful in the City I haven’t visited yet, but only because it’s been under lock and key every time I’ve had a go. Unlucky I guess, but one of these days…

I have been in the church many times without knowing anything of the history certainly enlightened now -thanks

Great story, fabulous building. I especially enjoyed the Thomas Beri plaque.

I wish I’d known this when I went to the church. I visited St Martin’s during London Open Garden Squares weekend (which alongside Open House is one of my favourite weekends of the year) as it is now managed by The Stationers’ Company, whose livery hall and garden are immediately behind the church: https://www.stationers.org/company/history-and-heritage/the-church-of-st-martin-within-ludgate-1092019

Thomas Beri’s monumental brass was once considered lost, damaged amongst the items stored at St Pauls during the war.

It was eventually found in the back of a safe – with the dark wooden back facing out – so it wasn’t noticeable, and was only looked for once they church realised they had a missing brass. The instigator of the search, who had the replica created at Walton-on-the-Hill, was informed by a phone call which just said “Luke 15:9” (rejoice for that which was lost is now found).

The Walton-on-the-Hill replica was made from a rubbing taken in the 1930s.

While the 2 brass are close to identical, there are a number of differences in the spelling of some words, and a few minor details in the figure, which allows you to work out which church the rubbing came from.

Thomas was originally from Liverpool, moving to London as a fishmonger – the endowment to the Parish still exists to this day, with the local school presenting a “Beri Prize”, although the 12 penny loaves goes towards bread for the vicarage and a local foodbank.

What a wonderful and informative talk on the less known Churches of the City of London. I will certainly make a point of looking out for these Churches next time I visit London.

In this interesting post, you write, “The text included evidence that the site was ancient as ‘several antiquities were discovered to prove it being a Roman burial-place’.” The tombstone of Vivius Marcianus, believed to have been a Roman Centurion, was found in the ruins of St. Martin’s after the Great Fire and is on display in the Museum of London.

‘there is a possibility that rather than Wren, it was Robert Hooke who was responsible for the church’. Is it possible to elaborate on this please? Thank you…

You do not mention a remarkable feature of the font at St Martins,namely the Greek palindrome round its rim.

This reads tripson anomeema me monan opsin,meaning Cleanse thy sins,not merely thy outward self.

Though now resident in NZ I was born in London and well remember my father fire-watchng at St Mart ins during WW2.he worked in St Pauls Churchyard

Could you help identify the exact location (in relation to present-day Ludgate Hill) of the shop of John Harvey & Son (drapers) in Ludgate Hill ? The Harvey family ran this shop from about 1810 to about 1865. The shop fronted on to Ludgate Hill, and behind it were older buildings in which lodged skilled workers who made haberdashery items for sale in the shop. The skills, and this location for these craftspeople, probably long predated the Harvey’s shop. When the shop was burnt out in the Ludgate Hill fire (sometime around 1830, I think) the shop re-opened with the first plate glass window in London. The building was called Gloucester House, and I think it was probably demolished some time in the 20th century. By the time the shop closed (which it did after the death of John Harvey who I think lived to about 80 years old) the business had expanded to a include mail order department.