I was in the City earlier this month and had a couple of free hours in the afternoon, so I headed to the church of St Stephen Walbrook, a church I have not been inside for a number of years.

The church is located just south of the Bank junction of Poultry, Princess Street, Threadneedle Street, Cornhill and King William Street. Located just behind the Mansion House, the church includes the name of one of the City’s lost rivers, and faces onto a street with the same name, Walbrook.

Walking down from the Bank junction, this is the view of the tower of St Stephen Walbrook:

St Stephen Walbrook has a long history, however the church is not on its original site.

The River Walbrook originally ran slightly to the west of the street, and it was on the western side of the River Walbrook that the first church was established. Foundations of the original church were found during excavation of the site that today is occupied by the offices of Bloomberg, also the original location of the Roman Temple to Mithras.

According to Walter Thornbury writing in Old and New London, “Eudo, Steward of the Household to King Henry I (1100- 1135) gave the church of St Stephen, which stood on the west side of Walbrook, to the Monastery of St John at Colchester.”

The church probably dates from around the 11th century, but is probably older.

There is very little written evidence of this first church, however in the History of the Ward of Walbrook of the City of London (1904), J.G. White states:

“It possessed a Steeple with Bells and Belfry, as, from an inventory made, it appears that at the time of building the new Church, three bells, with their wheels, &c., were removed from the old building, and fixed in the new Steeple; also that it contained a belfry is evident from the fact that there is in the Coroner’s Roll for 1278 an entry, that on the 1st May in that year information was given that on the previous Sunday, about mid-day, William Clarke ascended the belfry to look for a pigeon’s nest, and in climbing from beam to beam he missed his hold and fell, dying as soon as he came to the ground. There was also a Chancel, there being in the year 1300 an Inquisition taken to enquire who was liable to repair the watercourse of the Walbrook over against the Chancel Wall of the Church.”

Around 1428, this original location of the church, and its associated graveyard was considered too small to support the parish, so a new location was required.

A plot of land was given by Robert Chicheley, a member of The Worshipful Company of Grocers, on the opposite side of Walbrook street, roughly 20 metres to the east of the original location, and the new church was built between 1429 and 1439.

This church would last just under 240 years as the church of St Stephen Walbrook would be one of those destroyed in the Great Fire of 1666.

Rebuilding commenced in December 1672, with Wren as the architect. St Stephen Walbrook was probably his local church as at the time he was living in Walbrook.

It was a difficult location for the new church as houses were built up against the church, including the area around where the tower would be built.

The area north of the church, now the site of the Mansion House was originally occupied by a market in fish and flesh know as the Stocks Market. Part of the original design for completion of St Stephen Walbrook was a colonnaded replacement for the pre-fire Stocks Market, which would have extended north from the church, This did not get built.

The church was ready to use in 1679, although the tower appears to have been completed later.

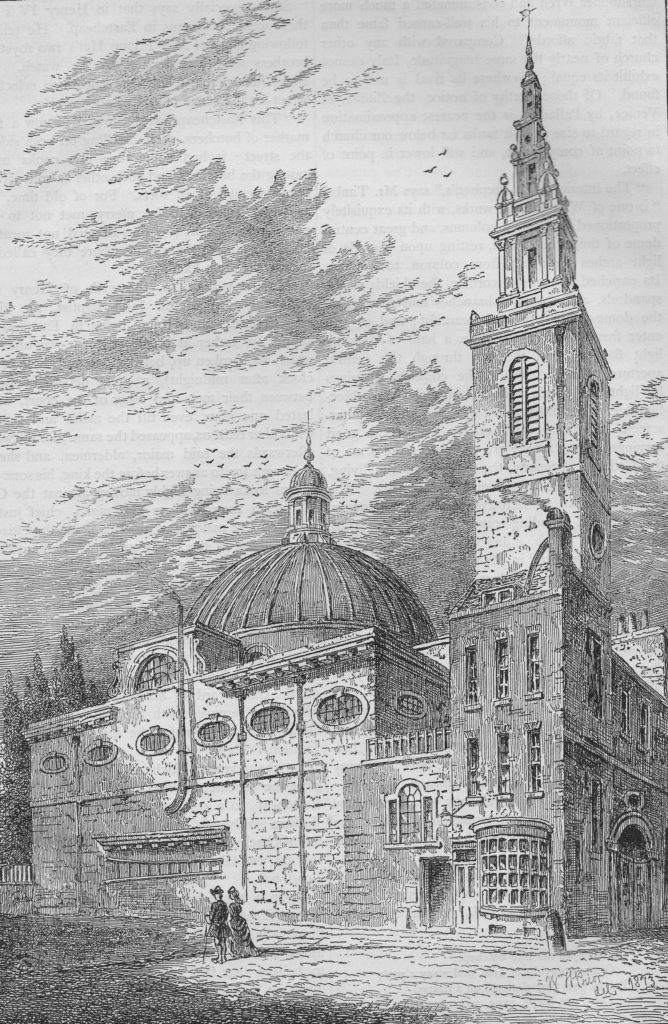

The following print from Old and New London shows the church soon after completion. The print also highlights the houses that clustered immediately around the tower.

The above drawing from Old and New London is dated 1700, however I suspect this is wrong. The drawing shows the spire on top of the tower, however the spire was not added until 1713-1715.

Remove the houses in front of the church, and as the following photo demonstrates, the appearance of the church is much the same today. It was not possible to replicate the above drawing as the Mansion House presses in to the left of the church, occupying the space that was the Stocks Market.

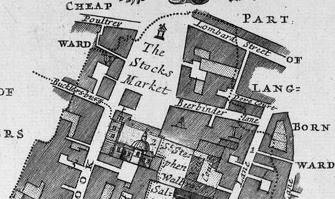

The following extract from a 1720 Ward map shows the church of St Stephen Walbrook, with the Stocks Market occupying the land to the north.

Time for a look inside the church. A set of steps rise up from street level to the interior of the church.

The interior of St Stephen Walbrook from the entrance:

The interior has an unusual layout for a City church. The wooden reredos is at the far end of the church where the altar would traditionally have been located, however following restoration work carried out between 1978 and 1987, the traditional altar was replaced by a central circular altar carved from Travertine by Henry Moore.

The new altar and additional restoration work throughout the church was commissioned and supported by the fund-raising efforts of Lord Peter Palumbo who was Churchwarden from 1953 to 2003.

Restoration work at the time was essential as the church was suffering from subsidence, possibly due to the long-term impact of the River Walbrook.

The location of the altar does prevent an ideal photograph of one of the main features of Wren’s designs – the large dome located above the central square of the church.

Multiple references refer to the dome as being Wren’s practice for the dome of St Paul’s Cathedral, however whilst the overall shape is similar, a dome with lantern on top, the size and construction method is very different.

Whilst the dome of St Paul’s has the inner false dome, with the layer of supports between inner and outer dome to transfer the load of the large stone lantern through to the body of the cathedral, the dome of St Stephen is a much more straightforward construction, however that does not detract anything from the beauty of a magnificent dome, designed in the 17th century on a City parish church.

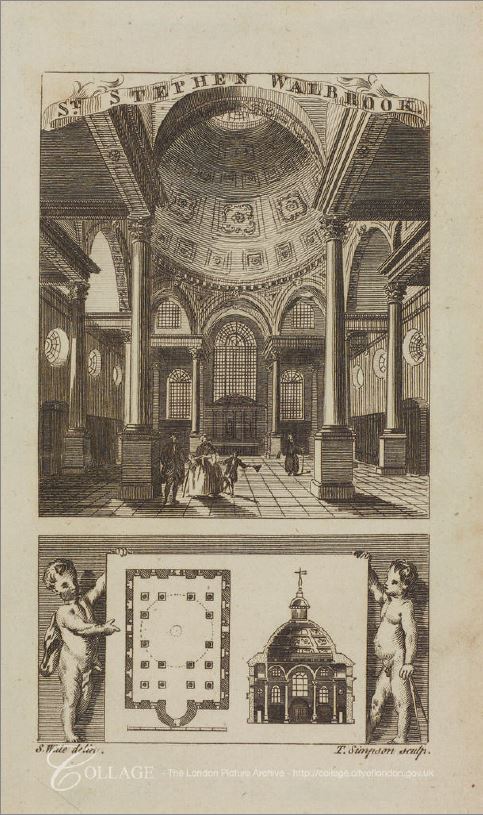

The following drawing from 1770 shows a view of the interior of the church, with below a cut away diagram of the dome’s construction and a floor plan of the church.

The interior of the church also shows another of Wren’s innovations. Rather than the weight of the dome being carried on a large pier at each corner, there are three slender columns at each corner. These have the effect of opening out the corners, rather than these spaces being occupied by a large load bearing pillar.

Note in the floor plan above that the tower is missing. The tower was added after the church had opened, and perhaps Wren’s idea was to have a rectangular church with no tower, where the dome rising above the church would have been the dominating feature.

When the exterior of the church is viewed today, the dome of the church is somewhat hidden to the rear with the tower dominating – perhaps not Wren’s original intention.

Whilst many writers praised St Stephen Walbrook as one of Wren’s best City churches, there were other views, for example in Curiosities of London (1867), John Timbs writes:

“This church, unquestionably elegant, has been overpraised. The rich dome is considered by John Carter to be Wren’s attempt to ‘set up a dome, a comparative imitation (though on a diminutive scale) of the Pantheon at Rome, and which, no doubt, was a kind of probationary trial previous to his gigantic operation of fixing one on his octangular superstructure in the centre of the new St Paul’s’. Mr J. Gwilt says of St Stephen’s ‘Compared with any other church of nearly the same magnitude, Italy cannot exhibit its equal, elsewhere its rival is not to be found. Of those worthy notice, the Zitelle at Venice (by Palladio), is the present approximation in regard to size, but it ranks far below our church in point of composition, and still lower in point of effect.’

Again, had its materials and volume been as durable and as extensive as those of St Paul’s Cathedral, Sir Christopher Wren had consummated (in St Stephen’s) a much more efficient monument to his well-earned fame than this fabric affords.”

The church suffered significant damage during the war. the following photo shows the interior of the church with parts of the dome collapsed onto the floor of the church.

Image credit: London Metropolitan Archives, City of London: catalogue ref: M0019488CL

A view of the damage to the dome can be seen in the following drawing by Dennis Flanders in June 1941.

Dennis Flanders was a freelance artists who recorded bomb damage to London. He sold some of his work to the War Artists Advisory Committee, including the drawing of St Stephen’s.

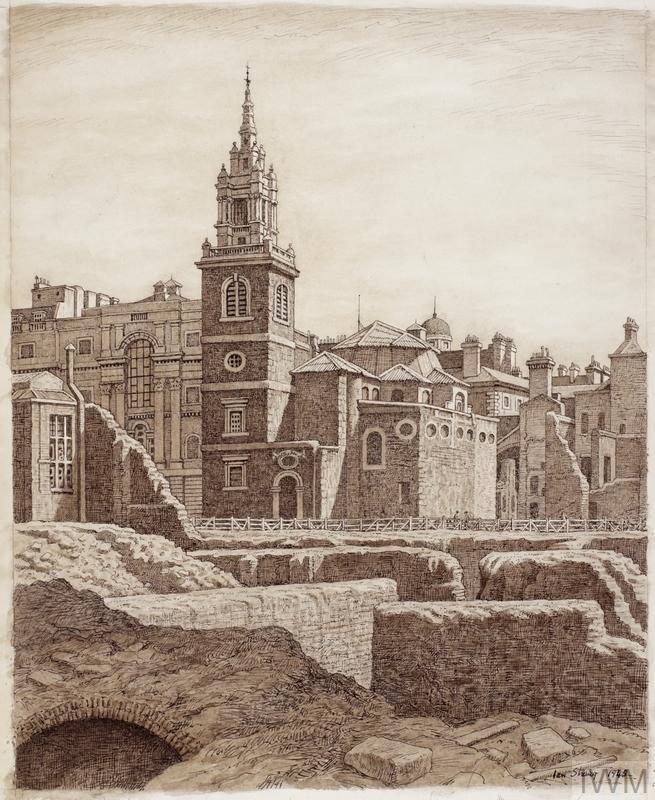

Another drawing purchased by the War Artists Advisory Committee was the following by Ian Strang, dated 1945.

Note the temporary wooden cover in the place of the dome.

In the foreground are the foundations of the bombed buildings that occupied the space now occupied by the Bloomberg building. Excavation in the space during 1954 would reveal the Roman Temple of Mithras.

There is a wonderful model of the church to be seen inside the church:

The model allows the overall design of the church to be appreciated, not easy when viewed from outside.

Looking at the model, the tower and buildings along the front of the church do look separate to the main body of the church (the smaller building to the right of the row on the front is a Starbucks).

Remove the tower and the buildings along the front and the church would be of rectangular design with a magnificent dome dominating the view of the church – perhaps Wren’s original intention.

The spire on top of the church is very similar to two other City churches, St Michael Paternoster Royal and St James Garlickhithe, which is shown in the following photo taken by my father in 1953.

The spire was added to St Stephen Walbrook between 1713 and 1715, and the spires to the other two churches were added in the same period. They are possibly to a design by Hawksmoor.

Looking back towards the entrance to the church with a rather magnificent organ case above the door. This dates from 1765.

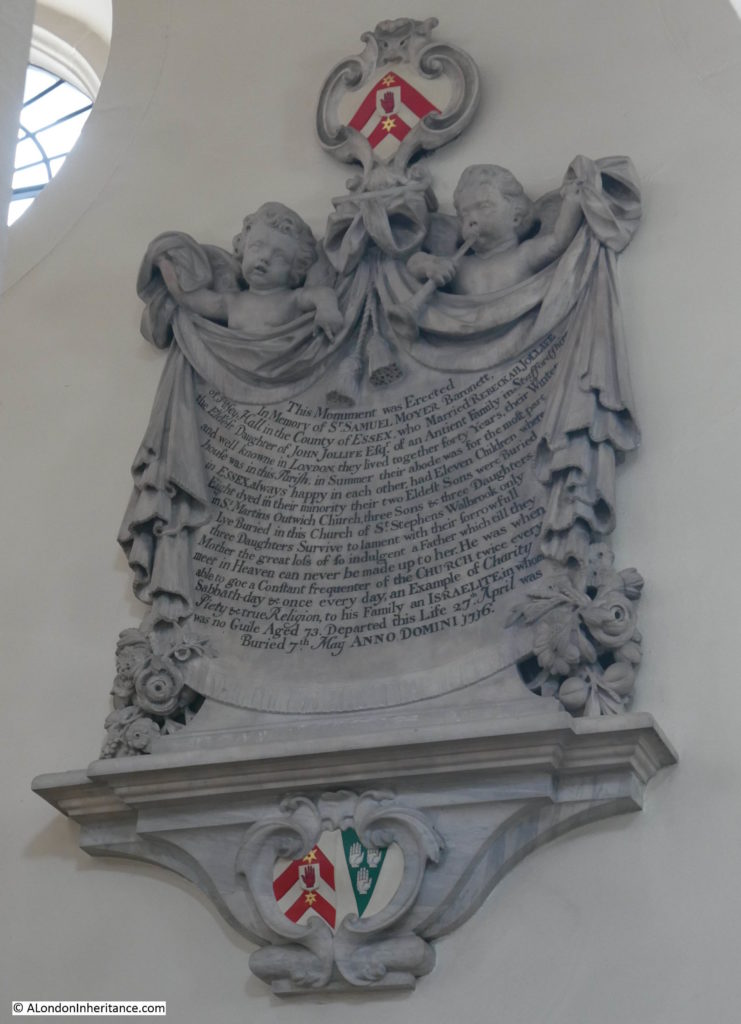

There are a number of monuments on the walls of the church, including the following to Samuel Moyer dated 1716:

Many of these tablets provide an insight into the dreadful child mortality rates of earlier centuries, even for those who were affluent.

The tablet states that Samuel Moyer was a Baronet. He must have had money as the tablet states the family spent the summer at their home at Pitsey Hall in Essex and the winters in the parish of St Stephen Walbrook.

A Baronet, who could afford homes in Essex and London still suffered numerous child deaths, Of their eleven children, eight died in their minority, with only three daughters surviving to “lament with their sorrowful mother, the great loss of so indulgent a father”.

It was not just the high rates of child mortality, but also what this level of child-birth did to women. The risks to women during childbirth were very high, and for Rebeckah Jollife, Moyer’s wife, surviving eleven must have been traumatic.

Also, with eleven births, for a significant period of her life, Rebeckah must have been in a state of almost continuous pregnancy.

St Stephen Walbrook also has a rather nice sword rest dating from 1710. This apparently came from the church of St Ethelburga.

Back outside the church and this is the view of St Stephen Walbrook from the south.

Today, a Starbuck’s occupies the corner space between tower and body of the church.

The dome of the church and lantern is just visible from the street.

The side view of the church shows the rough building materials used in the construction of the church – probably because other buildings were up against the side of the church so there was no need for expensive stone dressing to the side walls.

Close up view of the dome and lantern:

A longer view looking along Walbrook from the south. The Bloomberg building is on the left:

This is such a fascinating area. In the above photo, the River Walbrook once ran roughly from where I am standing to take the photo, up and parallel to the existing street. The original church was on the left, prior to moving across the street and the river. The Roman Temple of Mithras is under the Bloomberg building on my left.

St Stephen Walbrook still dominates the northern part of the street, however if you walk along the street, look behind the tower and admire Wren’s dome.

Very interesting as usual another one on the bucket list.

And well worth a visit on Friday lunchtimes for the organ recitals!

Excellent review. I especially liked the older pictures you used.

Interesting.

I used to work in Walbrook, just opposite St Stevens, in a pub called “Deacons” (IIRC), which was on the ground floor of the building which was situated where the Bloomberg building is now. (it may have been Bucklersbury House – I can’t remember)

Also, Chad Varah was the rector of St. Stevens for many years, and the founder of the Samaritans.

I worked in Buckersbury House and drank in Deacons often…

Another interesting post, thank you

Another hidden gem. I wish I had done more exploring in the early 1970`s when I lived in London …the ignorance of youth I`m afraid !!!

Stunning! Thank you

Regretfully, the Temple of Mithras seems to be under a Temple of Midas.

I’m guessing “Pitsey” is modern Pitsea, which has “Pitsea Hall Lane” running down from the A13 into the marshes – a notoriously unhealthy area even within my own lifetime. It’s now part of Basildon New Town and the site of a major rubbish tip serving all of South Essex.

The Hall is still there, close to the railways station, but known now as “Cromwell Manor” and used for weddings etc.

Not far up towards London is Rainham, where I once took a short cut through the churchyard and noticed how exceptionally short, even for historical days, the lifespans of the inhabitants were.

The whole area, right round the Thames Estuary and all up the Essex coastal estuaries and marshes, was a hotbed of malarial mosquitoes – if this family spent any time at their Manor I’m only surprised the parents lived as long as they did!

Thank you. This is one of my favorite spots when in the City on business. The church has a quiet meditation with a brief homily that runs ~ 20 minutes on certain weekday mornings most of the year. The space is exquisite, Moore’s altar fits in nicely in my opinion, and the fact that the Walbrook ran right in front down to the Thames is a further feature I enjoy as I imagine what it looked many centuries ago. I drop by here in the mornings before my meetings begin at 9-9:30 nearby. I also enjoy walking the periphery of the site, too. It has a small garden in back, which is open only a lunchtime. I’ve never visited it but it looks lovely.

The Temple of Mithras across Walbrook, in the basement of the Bloomberg Building, which opened last year, is also well worth visiting. The reconstruction and space were well done and an accompanying exhibit explains the cult of Mithras and the history of the site. One needs to book tickets in advance, but it’s easy to do online and the entire visit takes no more than 30-45 minutes.

My ancestor, Stephen Williams, a linen draper and calico printer, lived at no.27 Poultry from the mid-18th century until his death in 1797. The building was on the corner with the Walbrook. He leased the property from the Corporation of London and in the 1740s he employed the architect George Dance snr to draw up plans for the improvement of the property which had earlier been broken into. These plans can be seen at the London Metropolitan Archives. While his calico printing works were in Stratford, Essex, he carried out his wholesale linen business from no.27. When he died, his estate consisted of several leases and freeholds in the City and in Stratford which he bequeathed to his Williams and Burford nephews, his own children having pre-deceased him. He passed on the business and around £30,000, making several large bequests to non-conformist charities, and a staggering £10,000 to the Bank of England for the Government’s Loyalty Loan. I have yet to discover whether or it not it was ever repaid! By the time my great grandmother was born a hundred years later, the family were in very reduced circumstances, living in Bow where her father worked as a timber porter.