Continuing my series of posts, tracking down all the City of London’s blue plaques, here are another selection of the wide range of people and places commemorated across the City, starting with:

Mrs. Elizabeth Fry – Prison Reformer

Where Poultry meets the Bank junction, there is a plaque on a side wall recording that Mrs. Elizabeth Fry, Prison Reformer, lived here between 1800 and 1809:

Elizabeth Gurney, as she was before marriage, was born in Norwich in 1780. Her parents were Quaker’s, which probably influenced her future work.

She came to London in 1800, the same year that she had married Joseph Fry, so the plaque commemorates her first London home.

Her prison reform campaigning started around 1813 following a visit to Newgate prison. This visit was described in the book Prison Discipline by Sir Thomas Powell Buxton, and it really must have been a shocking sight:

“She found the female side in a situation which no language can describe – nearly three hundred women, sent there for every graduation of crime, some untried, and some under sentence of death, were crowded together in the two yards and the two cells.

Here they saw their friends and kept their multitude of children, and they had no other place for cooking, washing, eating and sleeping. They slept on the floor, at times one hundred and twenty on one ward, without so much as a mat for bedding, and many of them were nearly naked.

She saw them openly drinking spirits, and her ears were offended by the most terrible imprecations. Every thing was filthy to excess, and the smell was quite disgusting. Every one, even the Governor was reluctant to go amongst them. He persuaded her to leave her watch in the office, telling her that his presence would not prevent its being torn from her.

She saw enough to convince her that everything bad was going on. In giving me this account, she repeatedly said ‘all I tell thee is a faint picture of the reality; the filth, the closeness of the rooms, the ferocious manners and expressions of the women towards each other, and the abandoned wickedness which everything bespoke, are quite indescribable’. Two women were observed in the act of stripping a dead child, for the purpose of clothing a living one.”

As a result of this visit, Elizabeth Fry started to campaign for improved conditions for women prisoners. She started bible lessons in Newgate and in 1817 formed the Association for Improving the Condition of Female Prisoners in Newgate”. It was initially assumed that the association was doomed to failure and that prisoners in Newgate could not be reformed, however the association pushed forward. As well as the women, their concern was the condition of the children who were imprisoned with their mothers. The Association opened a school dedicated to children within the prison.

The Association’s work gradually brought about change:

“The efforts of the committee to induce order soon began to produce visible effects. It even excited surprise to watch their rapid progress to an almost total change of scene. The demeanour of the prisoners is now quiet and orderly, their habits industrious, their persons clean, their very countenances changed and softened. The governesses of the schools for children, and for adults, are themselves prisoners, whose steadiness and good conduct procured their selection, and have justified the preference.”

As well as work within Newgate, Elizabeth Fry campaigned for change in how prisoners were managed and in 1823 prison reform legislation was introduced in Parliament.

Her work expanded. She would sit with those who were condemned for execution, she visited convicts in prison ships prior to their being transported to Australia, and provided items such as blankets to provide some comfort during the voyage. She visited many other prisons to inspect their conditions and campaign for change. This included prisons across England and Scotland as well as France.

She corresponded with those in power across Europe, including the King of Prussia and the Dowager Empress of Russia.

Many people went to visit Newgate to see the improved conditions, and watch the work of Elizabeth Fry. Prince Albert and the Duke of Wellington met with her.

She was also interested in causes outside of prison reform, for example she also sent bibles and reading material to isolated coastguard stations across the country. She also campaigned for improved conditions for working women, improved housing for the poor, and she established a number of soup kitchens.

From 1809 to 1829 Elizabeth Fry lived in East Ham at Plashet House, then moved to a house in West Ham, where she lived until 1844. She then possibly moved to Kent as a year later she died at Upton, Ramsgate in Kent.

She was buried in the Friends burying ground in Barking.

Portrait of Elizabeth Fry (© The Trustees of the British Museum):

Elizabeth Fry apparently lived in St Mildred’s Court. I cannot find an exact location, however another blue plaque, a very short distance away indicates where the name of the court would have come from.

St. Mildred’s Church

Facing onto Poultry is another blue plaque:

Recalling the site of St Mildred’s church, demolished in 1872:

St Mildred’s church was one of the many City churches demolished during the second half of the 19th century. The City had been rapidly developing as a commercial centre. This reduced the number of residents and the size of church congregations. Space was also needed for road widening, additional office and commercial space, so many City churches, such as St Mildred’s were demolished.

An article in the Morning Post on the 18th of May 1872 provides some background to the church:

“The church of St. Mildred, Poultry, built by Sir Christopher Wren, is about to be sacrificed to the widening of the thoroughfare. It was erected in 1676 in the place of a decayed fabric which had dated from 1420, and which had superseded another of great antiquity that had fallen into dilapidation.

Previous to the first erection of the church, Thomas Morstead, surgeon to King Henry IV, V and VI, gave a piece of land adjoining the church, 45ft long and 35ft wide, for a burial ground.

Among persons of interest buried in the old church was Thomas Tusser, born in 1515, who wrote a book called ‘Points of Husbandrie’ which passed through 12 editions in 50 years. He is said to have led a wandering and unsettled life, being at one time a chorister, then a farmer, and afterwards a singing master. A quaint epitaph in verse commemorated his name and services. Previous to suppression of religious houses St Mildred’s belonged to the priory and canons of St. Mary Overy.

The length of the fabric now about to be taken down is 56ft, the width 42ft and the height 36ft. the tower is 75ft in height and is surmounted by a gilt ship in full sail.”

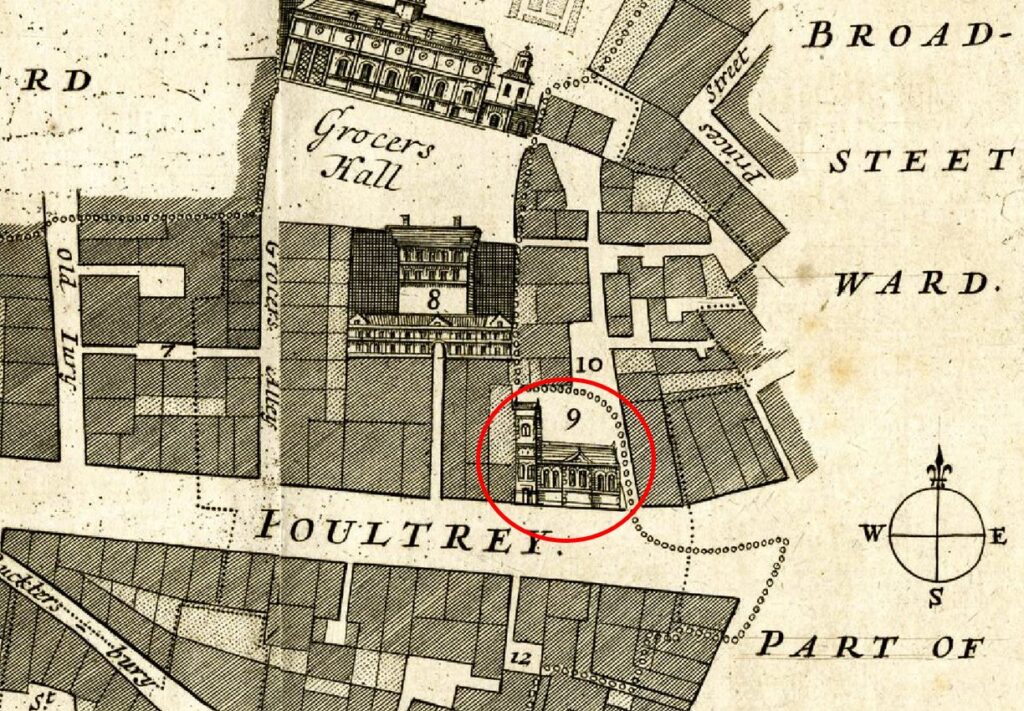

St. Mildred’s was shown on a 1754 map of Cheape Ward. I have circled the church in red in the following extract from the map:

In the above map, number 9 refers to St. Mildred’s church, and number 10 to Scalding Alley. I cannot find St Mildred’s Court on a map, so wonder if this was the alley by the side of the church.

When the church was demolished, the dead were relocated to the City of London cemetery at Ilford, Poultry was widened and new commercial buildings constructed on the site.

A short walk from Poultry, we find Tokenhouse Yard, a turnoff from Lothbury, where there is a plaque to:

Charles Brooking – Marine Painter

At the entrance to Tokenhouse Yard is a plaque to Charles Brooking who lived near the site of the plaque.

Not that much is known of the life of Charles Brooking. It is believed that he was born in Greenwich and he died at the relatively young age of 36. The plaque gives the years of his (assumed) birth (1723) and death (1759), not the years that he lived near the site of the plaque, and I cannot find when he did live near the site, or for how long.

The Illustrated London News provided some additional background on Charles Brooking at the time of an exhibition of his work at the Paul Mellon Foundation for British Art in 1966:

“A meticulous knowledge of shipping and a poetic lyricism in his observation of natural phenomena combine to make Charles Brooking the greatest of all marine painters. Born as he was in the 18th century his talents were perfectly fitted to satisfy the chauvinism engendered by Britain’s naval supremacy. What is remarkable is that Brooking’s painting avoids all forms of brashness and conceit which one almost expect. His high proficiency in technical detail and his emotional restraint are even alien to much of modern taste, which is a possible reason why Brooking has become a classic example of the great painter overlooked.

Brooking’s extraordinary technical ability in painting all kinds of naval gear make it reasonable to accept the inconclusive literary evidence that he came from Deptford and was trained in the dockyard there as the son of a master-craftsman at Greenwich Hospital. Seventeen twenty-three is an acceptable date for his birth, as he is known to have died in 1759 and was very probably 36 at the time.”

Most references to Charles Brooking put the brilliance of his work down to his early years being spent in and around Greenwich where he would have seen so much of the multitude of different types of ships in use during the early decades of the 18th century.

The following image shows one of Brooking’s works, dated from around 1755 and titled “Shipping in the English Channel”:

Source: Charles Brooking, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Tokenhouse Yard is an interesting little street. Built during the reign of Charles I on the site of a house and garden owned by the Earl of Arundel. The name comes from a building in the vicinity where the tokens issued by small traders as a replacement for small value coins, could be exchanged for legal tender

At the far end of Tokenhouse Yard, a small alley leads through the buildings at the end of the street through to Telegraph Street / Copthall Buildings:

Tokenhouse Yard, and the surrounding streets deserve a dedicated post, however the plaque to Charles Brooking at the entrance to the street does provide a reminder of a brilliant marine artist, who captured naval scenes during a couple of decades at the first half of the 18th century.

Also in Lothbury, is the site of the next plaque, to:

Founder’s Hall

Where Founders Court joins Lothbury there is a plaque recording that Founder’s Hall stood in the Court between 1531 and 1845:

Founder’s Hall was the hall of the Worshipful Company of Founders, one of the old Company’s of the City of London, dating back to 1365, when “In 1365 the men of the mistery of founders presented a petition to the mayor and aldermen stating that some of the mistery made ‘works of false metal and false solder’ and requesting that ordinances be approved to regulate the trade”.

The company may have been in existence prior to 1365, but it is this date which seems to be the accepted date for when the company came into existence, as a company that had powers to regulate aspects of their members trade.

Founders worked in brass, alloys of brass and tin, and produced articles such as candle sticks, stirrups for horses, pots etc. The basic materials of everyday life.

Their hall was built in 1531 when members of the Company purchased a number of houses and a garden in Lothbury, and constructed their hall.

Lothbury seems to have been the location of many who worked in the founders trade. Stow goes so far as to say that the name Lothbury comes from the number of founders who worked along the street, with their noise being found loathsome to those walking on the street, with the street attracting the name of Lothberie.

A Dictionary of London does not place much faith in Stow’s explanation, and suggests that the name comes from “lode” (a cut or drain leading into a large stream), with Lothbury leading over the Walbrook, or more probable the name coming from a personal name of Lod, or Loda.

The area around Lothbury has long been part of London’s populated history, as a Roman tessellated pavement was found opposite Founder’s Court at a depth of 12ft, along with a Roman pavement. Copper bowls were also found nearby at a depth of 10 ft. in wet, boggy soil.

I cannot find much about why the Founder’s vacated Founders Court. I did find a couple of newspaper articles from 1847 which hint at why they moved “TELEGRAPHIC CENTRAL STATION – The whole of the extensive buildings, including Founders Hall and Chapel in Founders Court, Lothbury, fronting the Bank of England, are being demolished, the Electric Telegraph Company having purchased the property for the formation of their central metropolitan station”.

The Electric Telegraph Company had been founded in the previous year, 1846, and was the world’s first public telegraph company.

Prior to the founding of the Electric Telegraph Company, the telegraph as a technology had mainly been used by the railways with wires being strung along railway lines in order to send messages between stations.

The Electric Telegraph Company was formed to offer the technology to potential users across business and the public. The Electric Telegraph Company could be compared with the earliest Internet service providers such as Compuserve, AOL, DELPHI and Earthlink, who took a technology that was used by a limited research and scientific community and opened it up to the wider public.

Some of the earliest users of the Electric Telegraph Company were the newspapers who suddenly had a means of receiving news at almost the instant it was happening. Initial use of this service was reported with some care, for example in a report in 1848, newspapers were detailing news of rebellions in Ireland, and included:

“The Electric Telegraph Company vouched for its arrival in Liverpool. On the whole, therefore, we did not feel justified in refusing to publish it. we inserted it just as it reached us, giving the authority, and at the same time stating that we have received nothing of the sort from our own correspondents”.

This statement from the papers of 1848 is a fascinating foretaste of what was to come, when new technology would continue to grow exponentially, the ability for news to flow in, before any trusted authority had been able to verify the source and factual basis of the news.

The Electric Telegraph Company grew during the following years, and merged with similar companies, eventually becoming part of the Post Office, and today, British Telecom.

The Founder’s then seem to have moved around a bit. Their next hall was in St Swithin’s Lane, and the current hall, dating from 1987, is located in Cloth Fair, opposite the Hand and Shears pub.

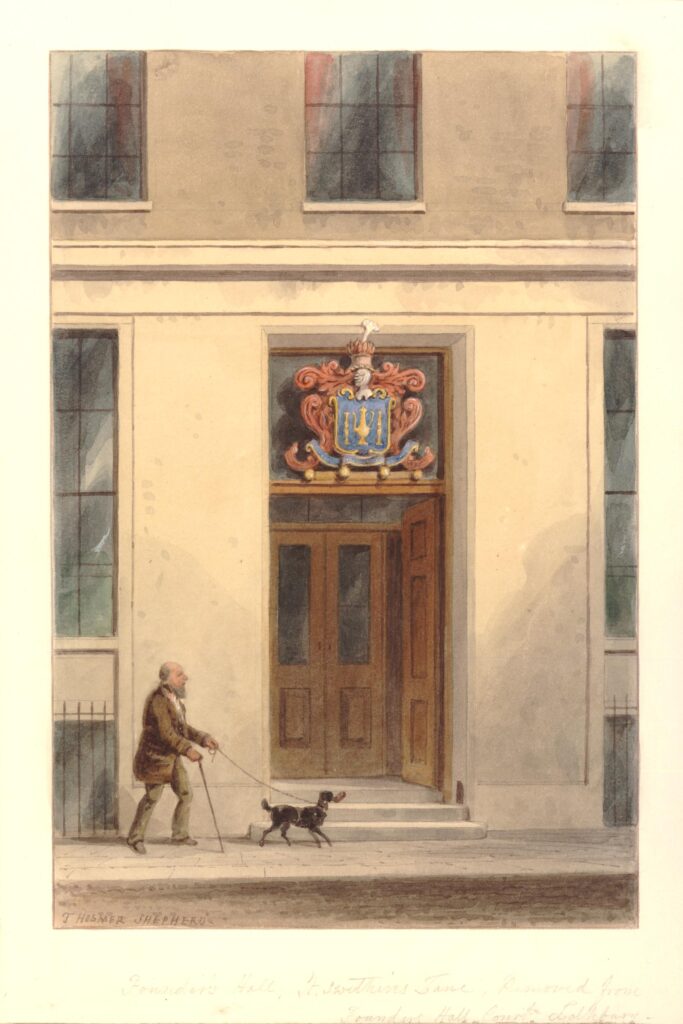

The following print, dating from 1855 shows the new Founder’s Hall in St Swithin’s Lane (© The Trustees of the British Museum):

Above the door is the coat of arms of the Founder’s, which consists of two taper candlesticks on either side of a laverpot (a container for filling a washing bowl) – both being examples of the Founder’s art.

Four more plaques which commemorate some of the people that have lived in the City and the buildings that have often been on the streets for centuries, but are now just recorded by a plaque on a wall.

Once again I read and learn so much from your interesting posts. Thank you for your time and effort most appreciated by me and many others.

Thanks once more for a very interesting post. My wife worked at Bart’s in the late 80s/early 90s, so would occasionally pick her up there, and use one of the Smithfield pubs. The Hand and Shears was always well used by staff from the hospital. However I’m afraid that I failed to notice the Founders Hall! As I recall Cloth Fair was where John Betjeman lived for a time. The only time I saw him in person was as a boy at St Barnabas church Pimlico, where I was in the choir in the late 50s. He attended services there on two or three occasions

What horrific conditions at Newgate prison awful life for people at the margins of society.

Trying to find out more about the Bank of England Club that used to be at 19 Tokenhouse Yard in at least the early-mid 1900s – so difficult to find information about it! But interesting to see photos of the laneway at least. Thank you for your interesting posts.