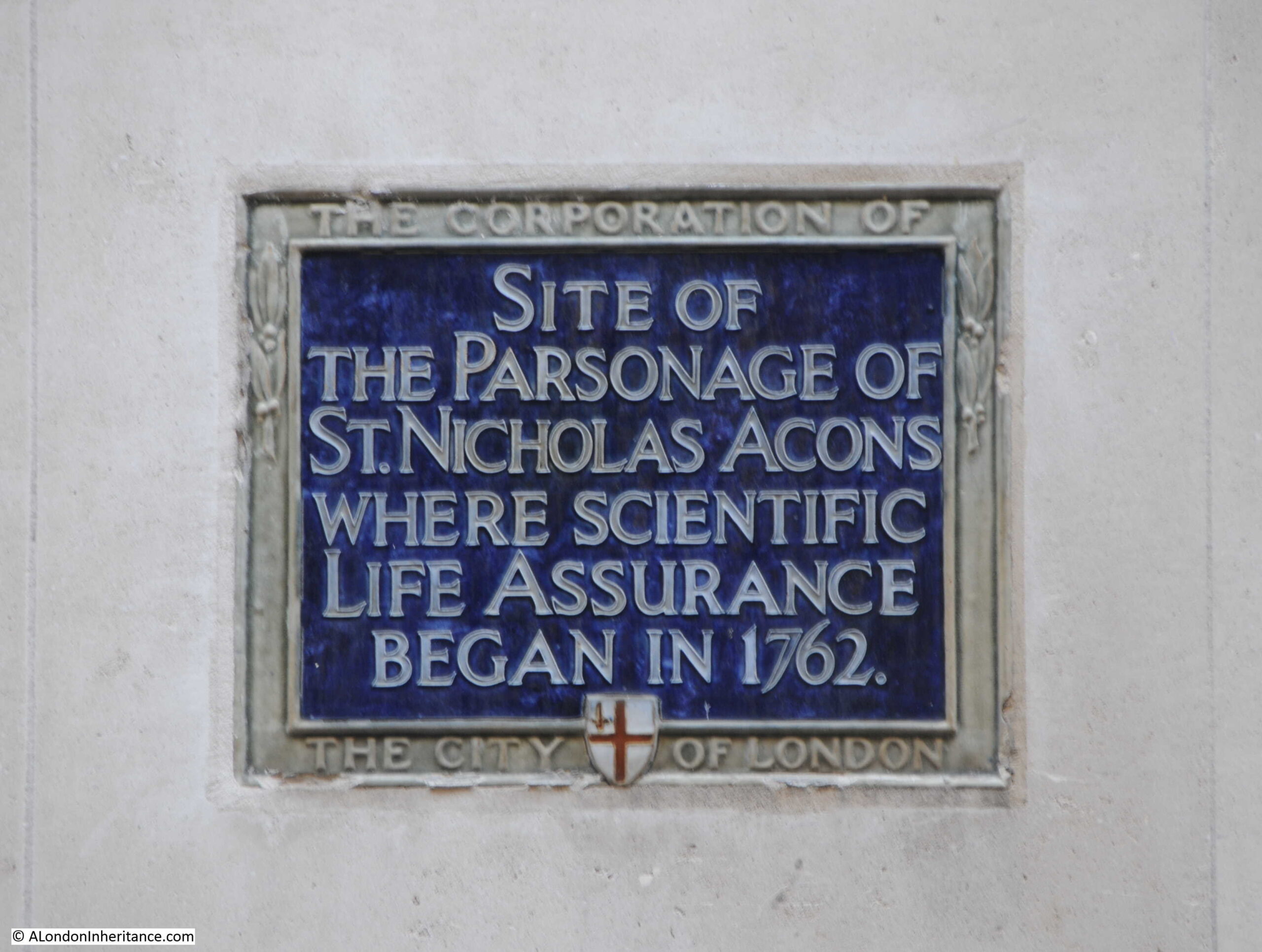

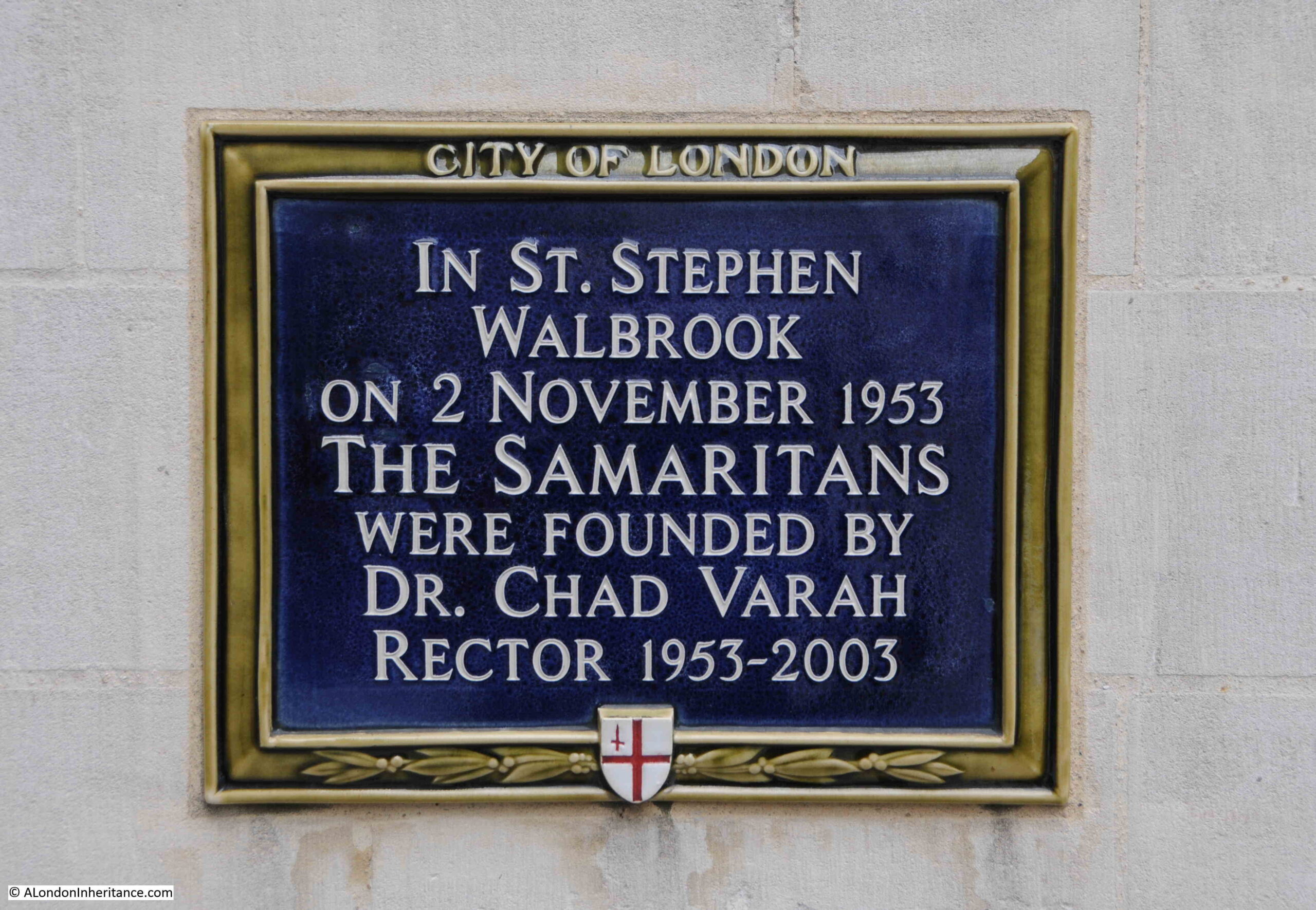

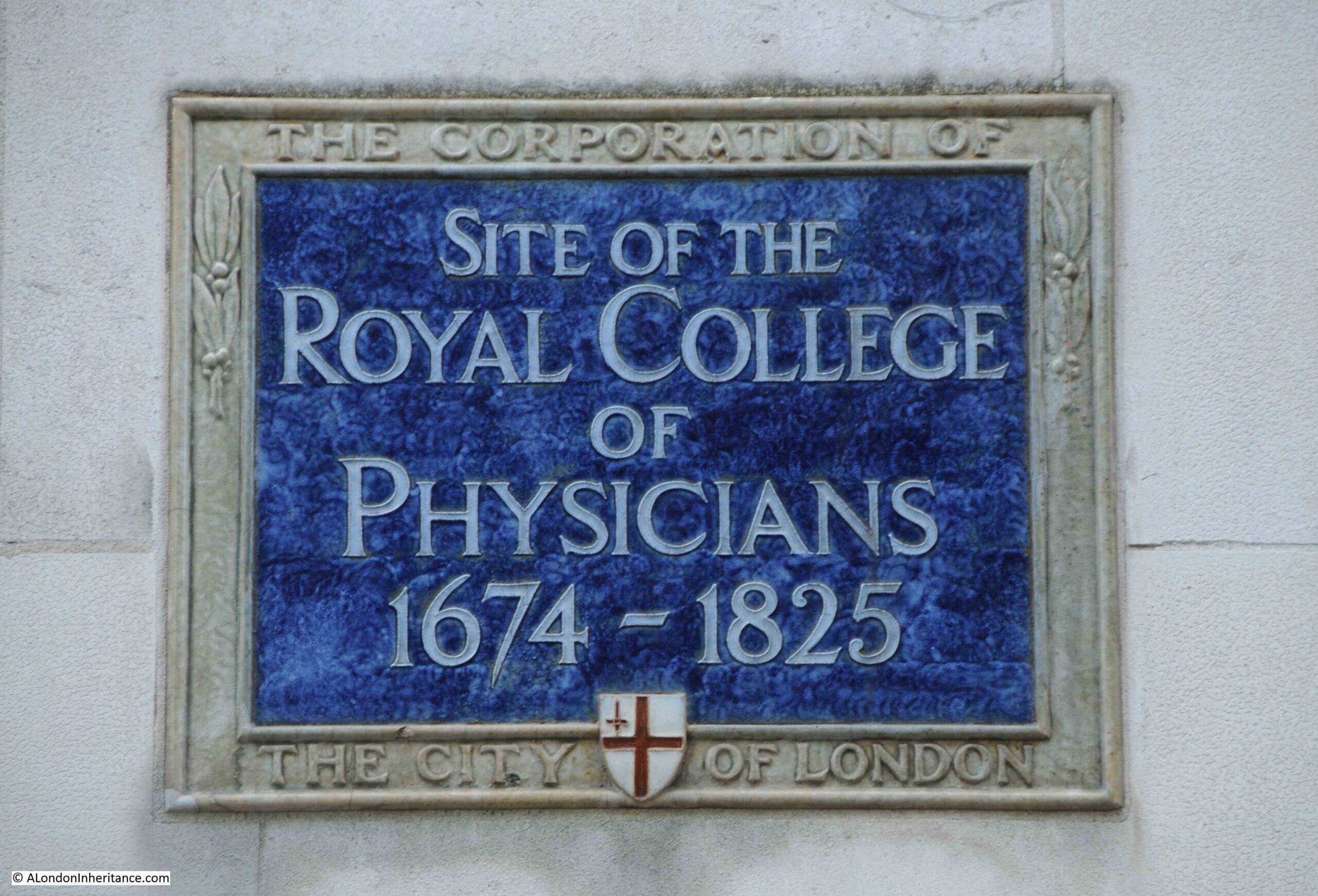

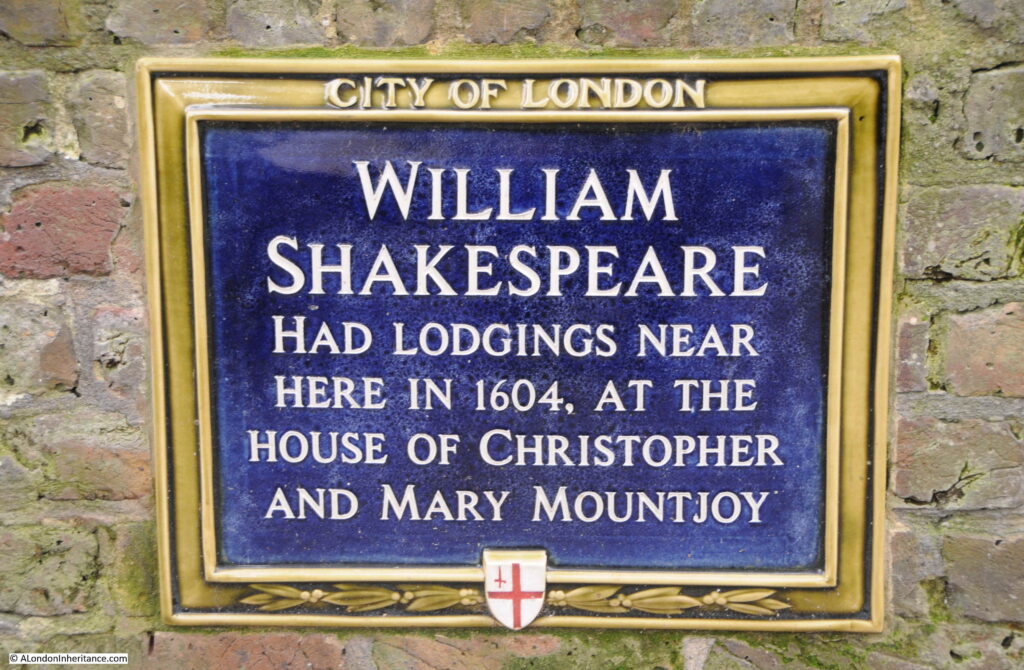

For this week’s post, I am returning to the plaques that can be found around the City of London. I originally started this series of posts with just the City Blue Plaques, however there are so many interesting stories to be found in other types of monuments and plaques around the City of London, that I have since broadened the scope of these posts.

Today’s post starts with a monument to Admiral Arthur Phillip, who provides the connection that is the title of the post – From Bread Street to Australia.

Admiral Arthur Phillip, R.N. Citizen of London

If you walk to the western end of Watling Street in the City of London, towards St. Paul’s Cathedral, you will come to an open space, with gardens on the left and the shops of One New Change on the right.

Tucked in the southern part of the space, up against the gardens is a small monument:

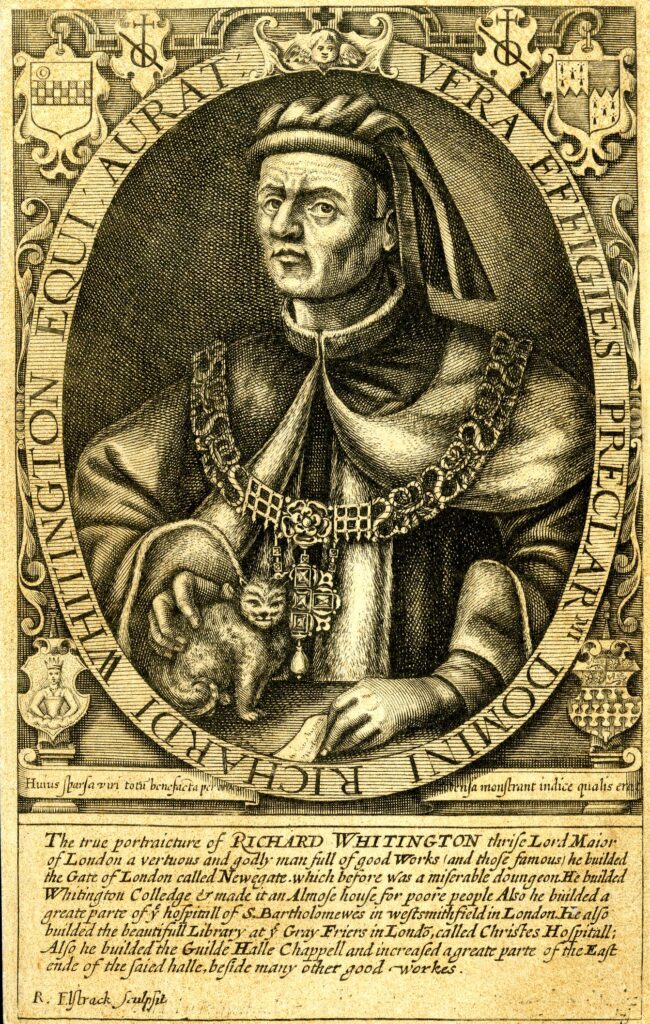

The monument is to Admiral Arthur Phillip, Royal Navy, and it is a bronze bust of Phillip that sits at the top of the monument. The bust was rescued from the church of St. Mildred, Bread Street, after the church had been destroyed by bombing in 1941.

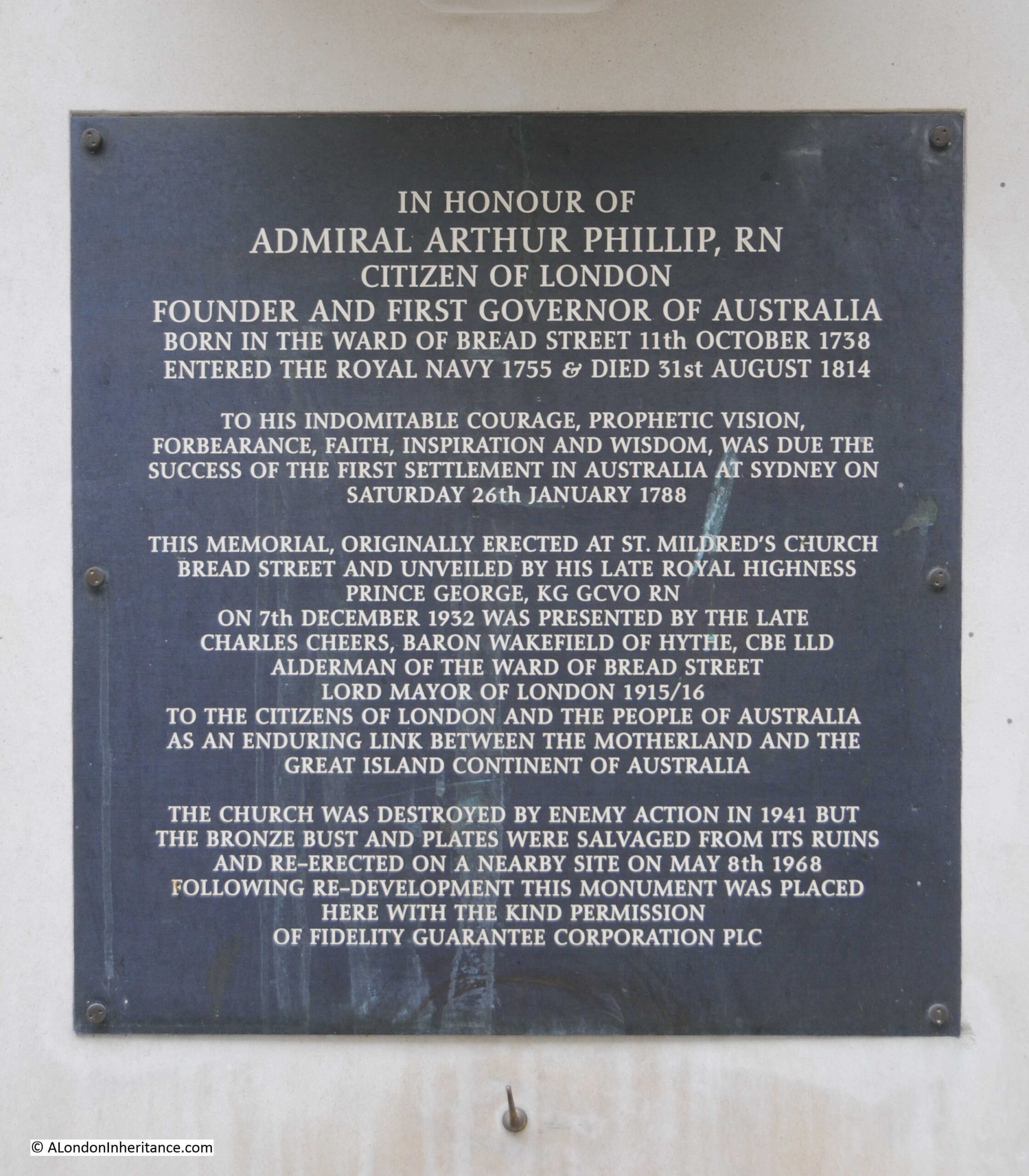

A plaque below the bust provides some background:

As the plaque states, Admiral Arthur Phillip was born in the ward of Bread Street on the 11th of October 1738. He went to the Royal Hospital School at Greenwich, and joined the Royal Navy in 1755.

In his time in the Navy, he was involved in the Battle of Menorca and the Battle of Havana, but after these battles he was left without a ship, and as was the custom at the time, naval officers had to find other sources of employment and Arthur Phillip took up farming in Hampshire.

In 1769, he rejoined the Royal Navy, and in the following years was involved in a number of battles around the world.

Although his time in the Navy appears to have been successful, if he had not been appointed the first Governor of Port Jackson, which he also named Sydney, after his friend Lord Sydney, his name would probably have been very little known today, and not commemorated in the City of London.

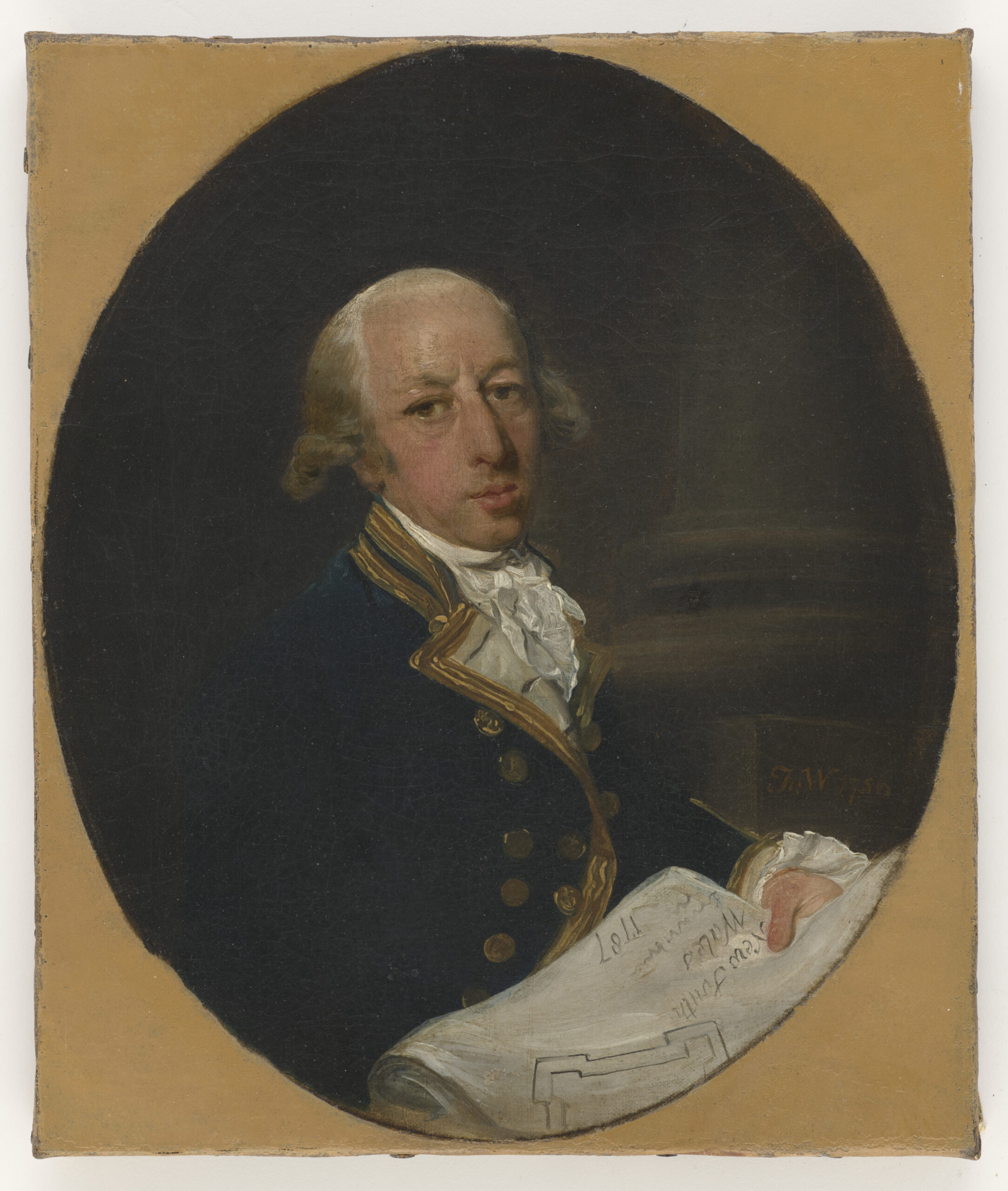

The following portrait shows Captain Arthur Phillip, as he was in 1786. The portrait is by Francis Wheatley:

I found a newspaper report from 1936 regarding a commemoration service to be held in St. Mildred’s, Bread Street for Admiral Arthur Phillip, and the article provides some additional information on his expedition to Australia, and the founding of the settlement at Port Jackson, which would later become part of the city of Sydney.

“Admiral Arthur Phillip, for whom a commemoration service will be held at St. Mildred’s Church, Bread Street, London on Tuesday, commanded the Sirius on an expedition to New South Wales some years after it had been discovered in 1770 by Captain Cook.

The expedition, which first arrived at Botany Bay, consisted of an armed trader, three store ships, and six transports. The persons on board the fleet included 40 women, 202 marines of various ranks, five doctors, a few mechanics, and 756 convicts. The live stock included cows, a bull, a stallion, three mares, some sheep, goats, pigs, and a large number of fowl. Seeds of all descriptions were provided for planting in the strange land, but Botany Bay was found unsuitable for settling upon. The expedition finally ended at Port Jackson, near the present site of Sydney.

Later on, other convict ships arrived, and in 1793 came the first free settlers, who were presented with grants of land.

The memorial service in London to the admiral will be attended by the Lord and Lady Mayoress of London, Lord Wakefield of Hythe, and the Sheriffs of the City, while Sir Archibald Weigall, Governor of South Australia from 1920 to 1922, will give the address”.

As the plaque states, St. Mildred’s, Bread Street, was destroyed during the Second World War, and was not rebuilt.

Although the original church has been lost, the memorial service continues to this day, and is currently held annually in St. Mary-le-Bow, Cheapside.

Arthur Phillip was in charge of the first fleet of convicts that had sailed from England to start the first colony in Australia.

The first fleet was the result of ideas that had been put forward for how Australia should be colonised, and what to do with the numbers of convicts which were seen to be a cost to the state, and how they could be usefully employed.

The following newspaper extract is from the 5th of November 1784:

“A plan has been presented to the minister, and is now before the cabinet, for instituting a new colony in New Holland. In this vast tract of land, which is so extensive as to participate of all the different temperaments or climates which affect the globe, every sort of produce and improvement, of which the various soils of the earth are capable, may be expected.

It is therefore proposed to send out the convicts to this place, under such regulations as may tend to the establishment of a new colony.

The only inhabitants which are thought to possess New Holland, are a few tribes of harmless uncultivated people, who loiter on the shore, and are only to be found in some creeks which seem convenient at once for shelter and provision, so that from there the European can have but little to fear, especially as it may be supposed no settlement will be attempted without sufficient force, at least in the first instance, to protect it from every species of surprise or depredation.”

It is horrendous to read, 240 years later, the lack of any interest in the history and culture of the indigenous population, and to understand what their fate would be over the years after the first fleet’s arrival.

The name New Holland in the above article is the first European name given to the continent of Australia in 1644 by the Dutch explorer Able Tasman who was employed by the Dutch East India Company, and after whom the island of Tasmania would be named.

There are a couple of reliefs on the monument, one on each side. The following shows “The discovery and fixing of the site of Sydney on Wednesday 23rd January 1783. Reading from left to right, Surg. J, White, R.N. Capt. Arthur Phillip, R.N. Founder, Leut. George Johnston, Marines, A.D.C. Capt. John Hunter, R.N. and Capt. David Collins, Marines”.

The second relief shows “The founding of Australia at Sydney on Saturday, 26th January 1788. Figures in rowing boat leaving H.M.S. Supply are Capt. Arthur Phillip, R.N. Lieut. P. Gidley King, R.N. and Lieut. George Johnston, Marines A.D.C.”:

Whilst the reliefs show a heroic view of the arrival at Port Jackson / Sydney, the reality of living at the settlement in the years after was rather challenging.

The following letter is from the Kentish Gazette on the 2nd of June, 1789. It provides a very honest view of the terrible conditions of the first settlers, and also their interaction with the indigenous population, who are described as “savages”.

“The following from Port Jackson, is written by a female pen; and as from a particular circumstance it seems an upright picture of the place, we lay it before our readers.”

The letter was written in Port Jackson on the 14th of November, 1789, and the author of the letter is not named.

“I take the first opportunity that has been given us, to acquaint you with our disconsolate situation in the solitary waste of the creation. Our passage, you may have heard by the first ships, was tolerably favourable; but the inconveniences since have suffered for want of shelter, bedding &c. are not to be imagined by any stranger. However, we have now two streets, if four rows of the most miserable huts you can possibly conceive, deserve the name; windows they have none, as from the Governor’s house, &c. now nearly finished, no glass could be spared; so that lattices of twigs are made by our people to supply their places.

At the extremity of the lines, where, since our arrival, the dead are buried, there is a place called The Church Yard; but we hear as soon as a sufficient quantity of bricks can be made, a church is to be built, and named, St. Philip’s after the Governor’s namesake. Notwithstanding all out presents, the savages still continue to do us all the injury they can, which makes the soldiers duty very hard, and much dissatisfaction among the officers. I know not how many people have been killed. As for the distress of the women, they are past description, as they are deprived of tea and other things they were indulged in, in the voyage by the seamen; and as they are all totally unprovided with clothes, those with young children are quite wretched. Besides this, though a number of marriages have taken place, several women who became pregnant on the voyage, and are since left by their partners, who are returned to England, are not likely, even here, to form any fresh connections.

We are comforted with the hopes of a supply of tea from China, and flattered with getting riches when the settlement is complete, and the hemp the place produces is brought to perfection. Our Kangaroo cats are like mutton, but is much leaner; and here is a king of chickweed so much in taste like our spinach, that no difference can be discerned. Something like ground ivy is used for tea; but a scarcity of salt and sugar makes our best meals insipid. The separation of several of us to an uninhabited island was like a second transportation. In short, every one is so taken up with their own misfortunes that they have no pity to bestow on others. All our letters are examined by an officer; but a friend takes this for me privately. The ships sail tonight.”

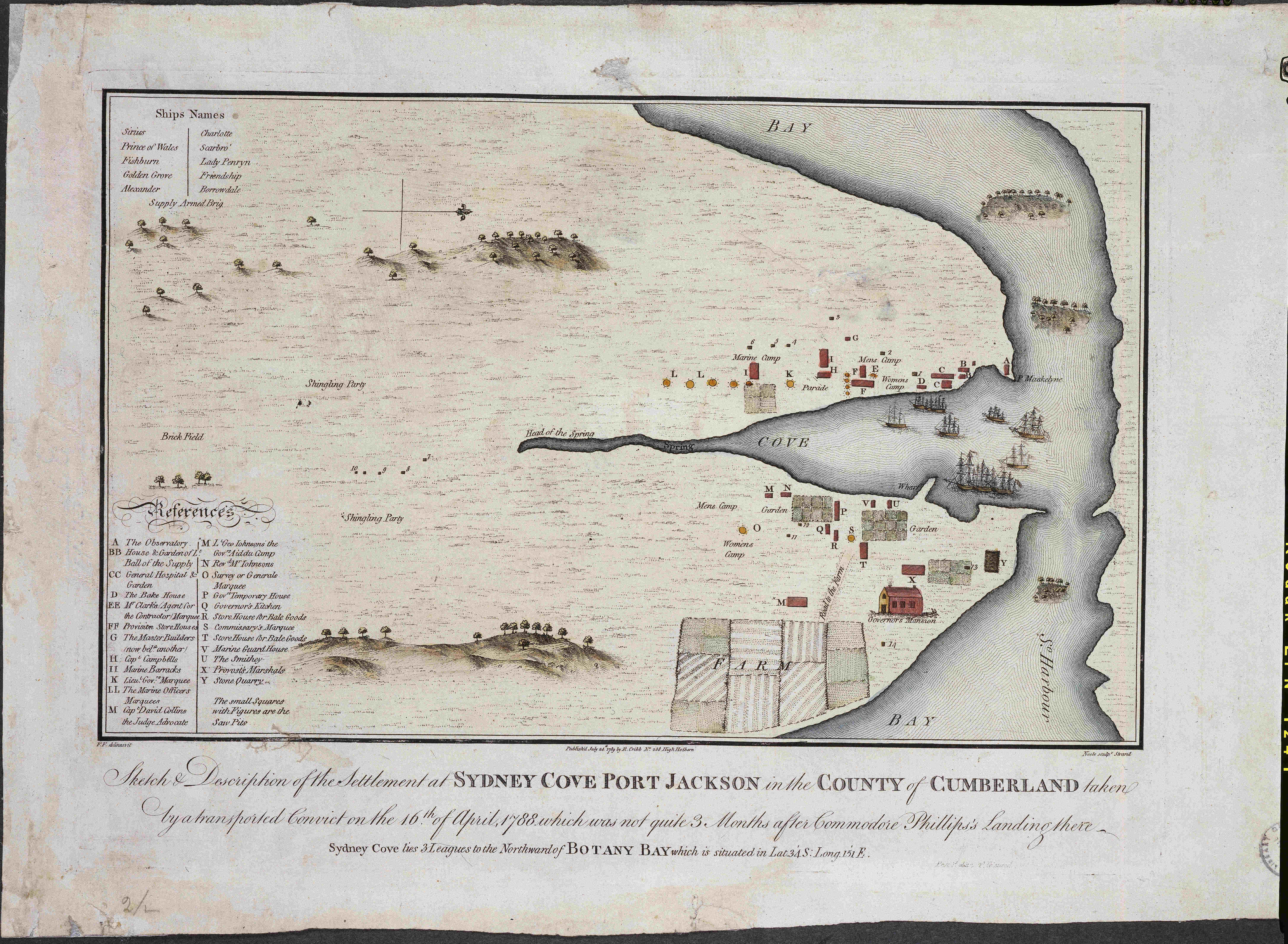

The following map is from 1789, the same year as the above letter, and shows how small the settlement at Sydney Cove Port Jackson was, and features from the letter can be seen in the map. Arthur Phillip’s ship, the Sirius, is shown in the bay. The ships are numbered and identified at top left.

Map source: State Library of New South Wales

The description to the map is “Sketch & description of the settlement at Sydney Cove Port Jackson in the County of Cumberland taken by a transported convict on the 16th of April, 1788, which was not quite 3 months after Commodore Phillips’s landing there”.

When looking at the above map, it is remarkable that this small settlement developed into what is now the city of Sydney.

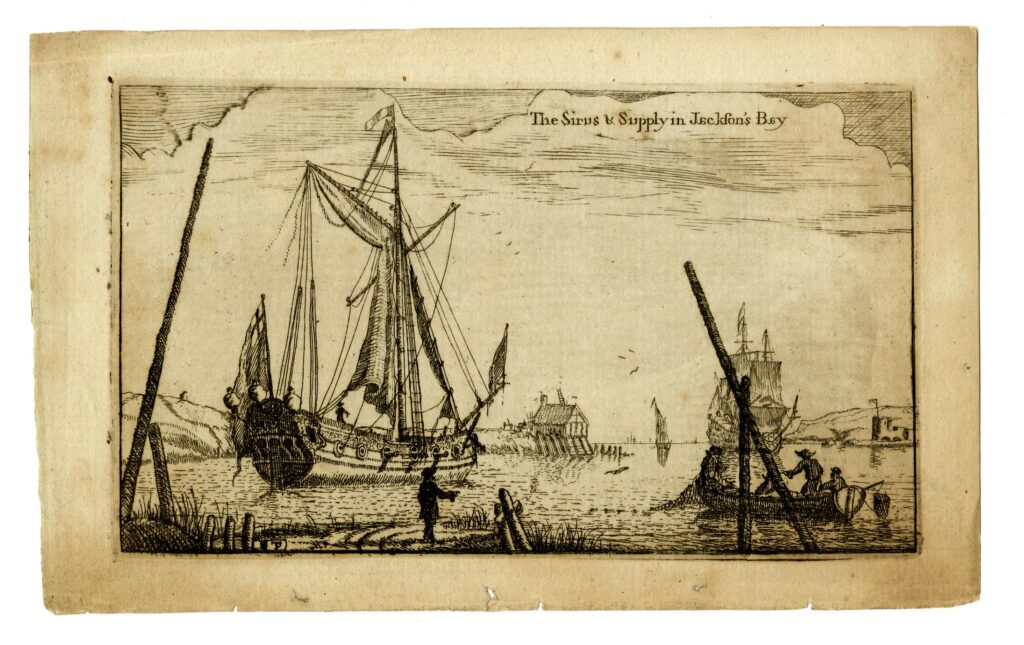

The following print shows H.M.S. Sirius and Supply, the ships of the First Fleet to arrive at Jackson’s Bay ( © The Trustees of the British Museum):

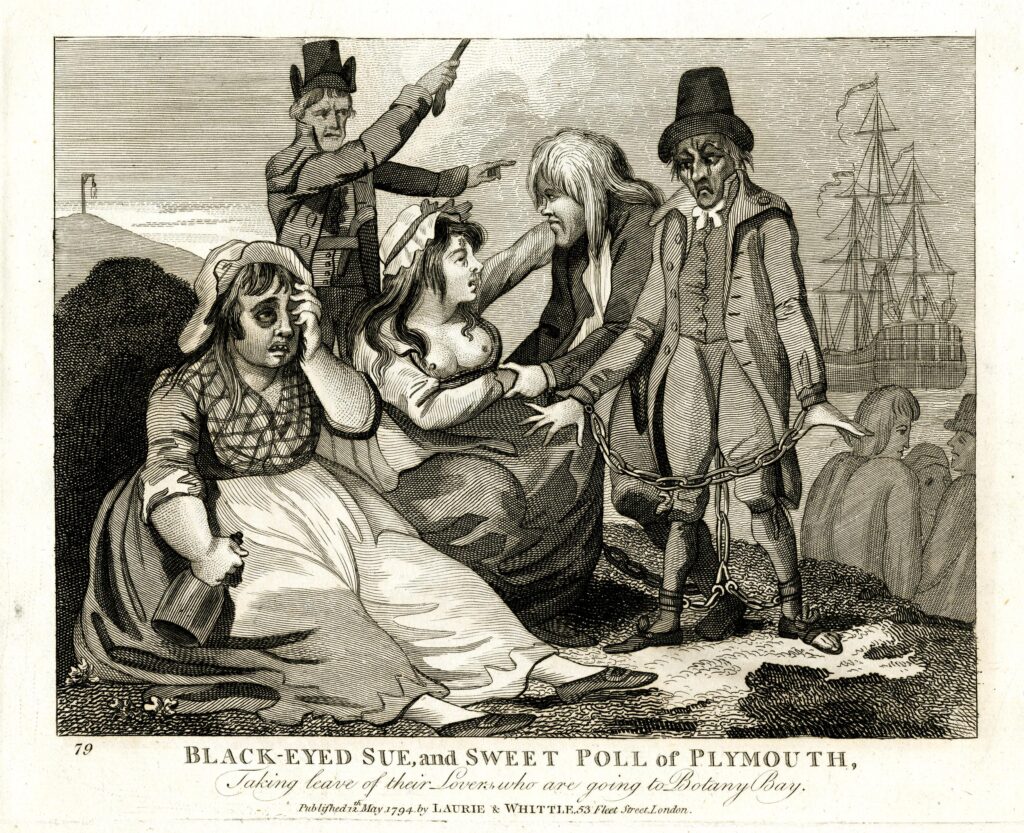

The majority of people arriving in the new settlement in the years at the end of the 18th century were convicts, and these featured in many prints of the time.

The following print shows “Black-Eyed Sue and Sweet Poll of Plymouth, taking leave of their lovers who are going to Botany Bay” ( © The Trustees of the British Museum):

In the print, the jailer is shown urging the two convicts to get on the ship which will take them to Australia, and perhaps to remind them of what they have escaped, there is a gallows on a hill in the background.

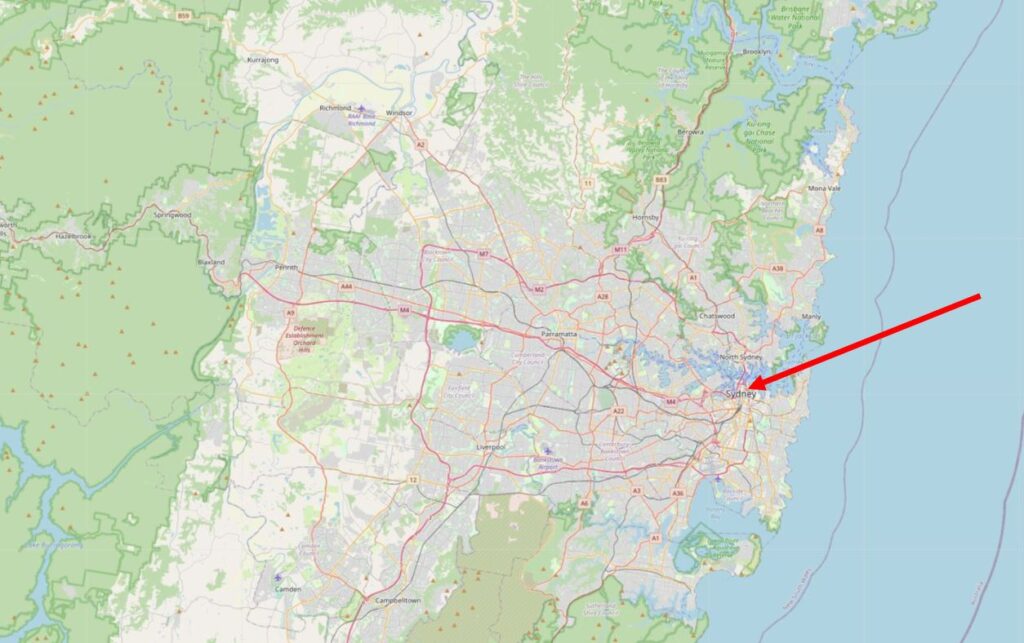

After a challenging start for the colony at Port Jackson, the rest of Australia would gradually be colonised, and the original site of Port Jackson would grow into the city of Sydney that we see today.

The following map shows the size of the city of Sydney, and I have marked the location of the original colony in the area around Sydney Opera House and the Sydney Bridge (© OpenStreetMap contributors):

In just under two weeks time, on January the 26th it will be Australia Day, which commemorates the landing of the First Fleet, and the day on which Arthur Phillip from Bread Street in the City of London raised the Union flag at the first colony.

St. John the Evangelist, Friday Street

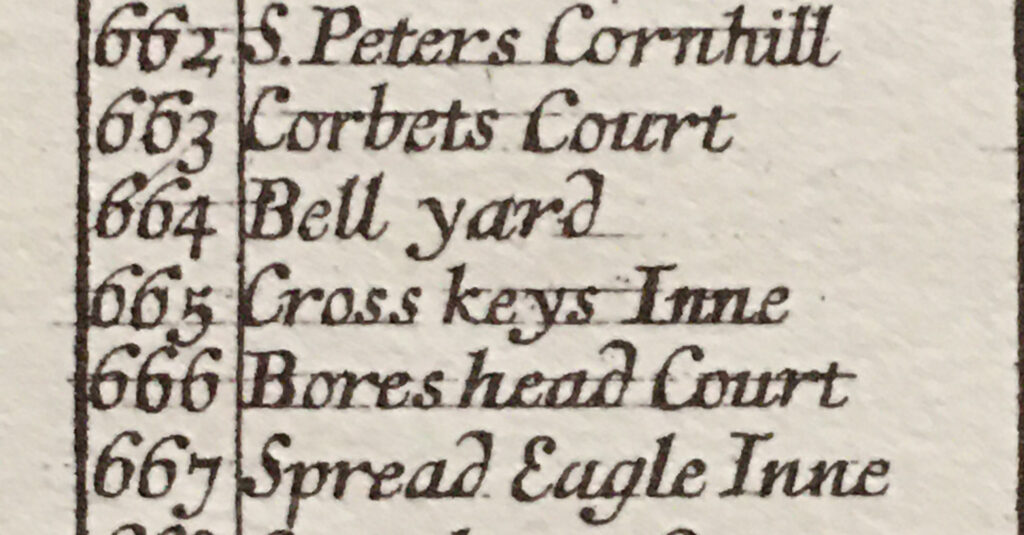

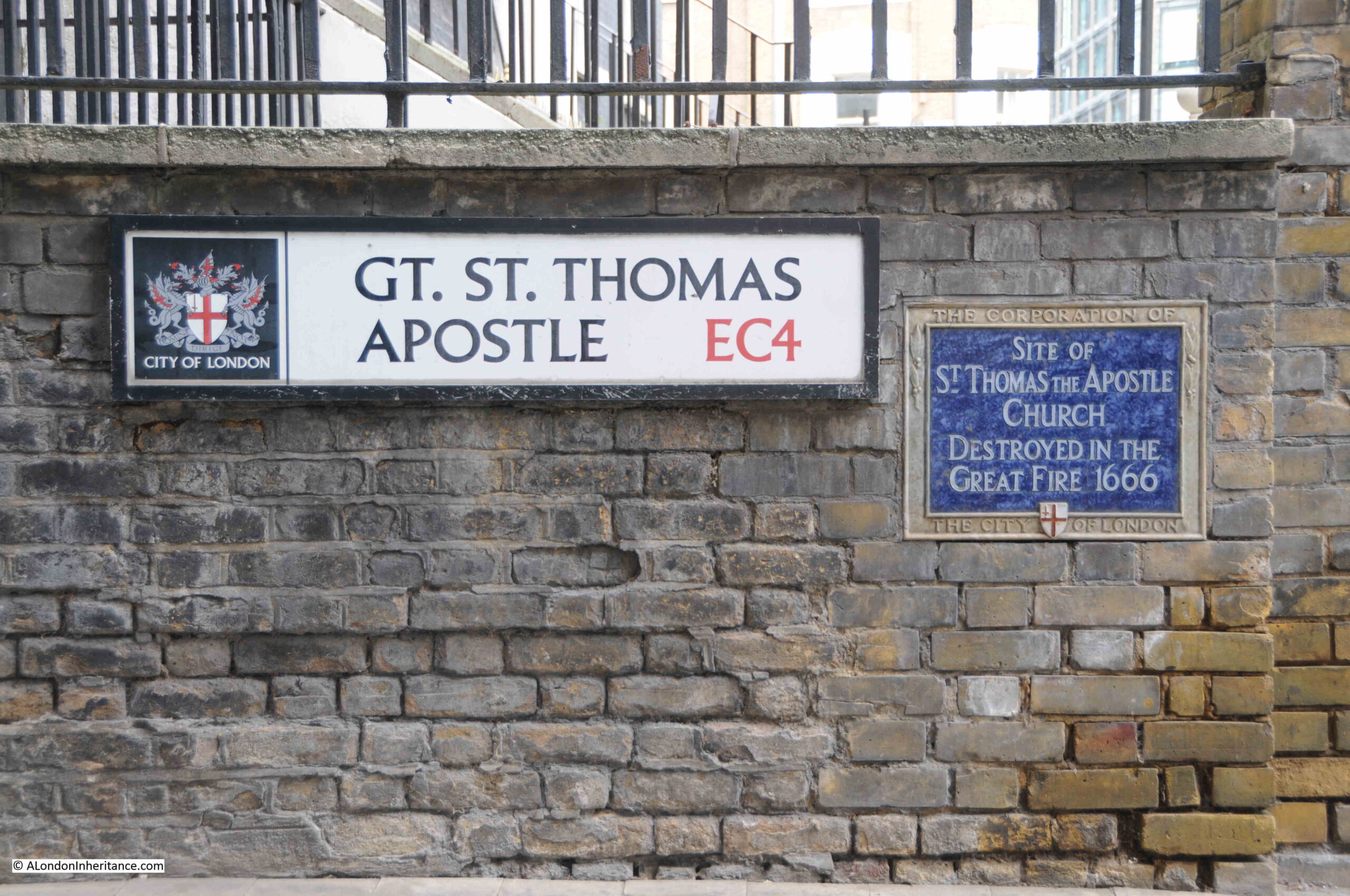

Next to the monument to Arthur Phillip is one of the City of London blue plaques, recording that it was the site of the church of St. John the Evangelist on Friday Street, and that the church was destroyed in the Great Fire of 1666:

There is not much to be found about the history of the church. In “London Churches Before The Great Fire” by Wilberforce Jenkinson (1917), there is the following paragraph about the church:

“At the end of Friday Street, at the corner of Watling Street, stood the church of St. john the Evangelist, one of those known as a ‘Peculiar’. In 1361 a chantry was founded by William de Augre. The first rector was Joh. Hanvile, who retired in 1354. The income of the benefice was returned in 1636 as £76, 10 shillings. After the Fire the parish was annexed to that of All Hallows, Bread Street. A small portion of the churchyard at the corner of Watling Street may still be seen.”

The church was known as a ‘Peculiar’, and the book gives the following definition:

“Peculiars were exempt from ordinary jurisdiction. The name of Peculiar was given to thirteen churches, of which Bow Church was the chief, and signified that they were exempt from the jurisdiction of the Bishop of London and were under the Archbishop of Canterbury”.

The plaque can be seen in the following photo on the wall on the right. One New Change is the building in the background, and the monument to Arthur Phillip is on the left, behind the greenery.

The church stood in Friday Street, and according to “London Past and Present” by Henry Wheatley (1891), the origin of the name is:

“So called, says Stow of fish mongers dwelling there, and serving Friday’s market.”

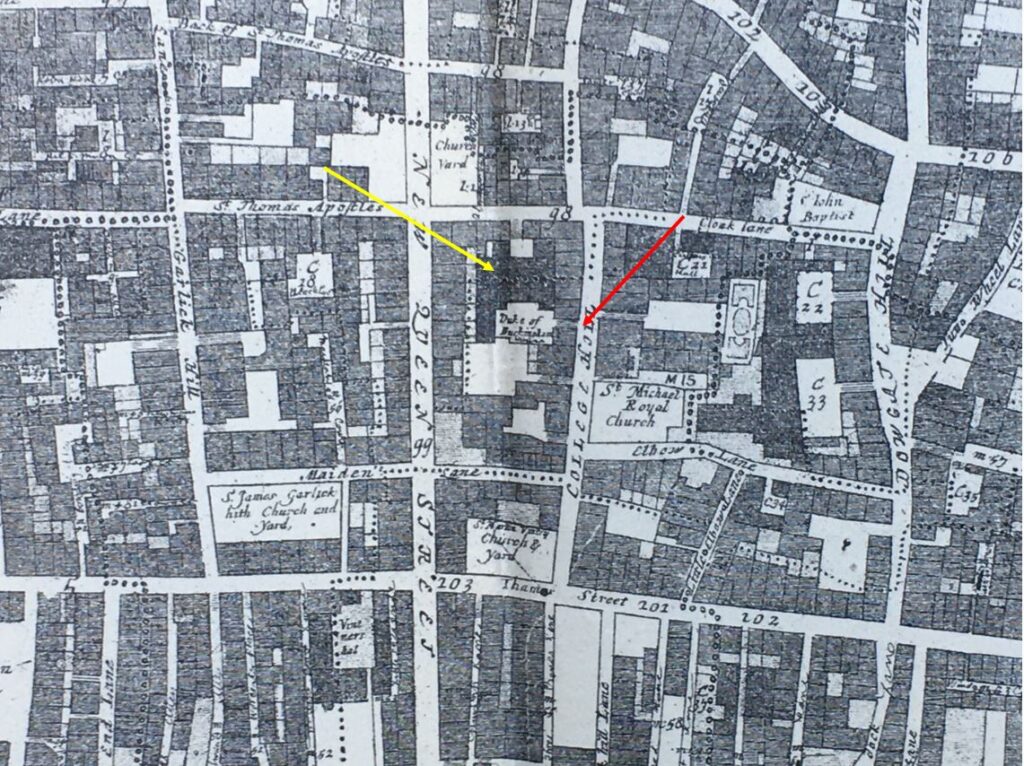

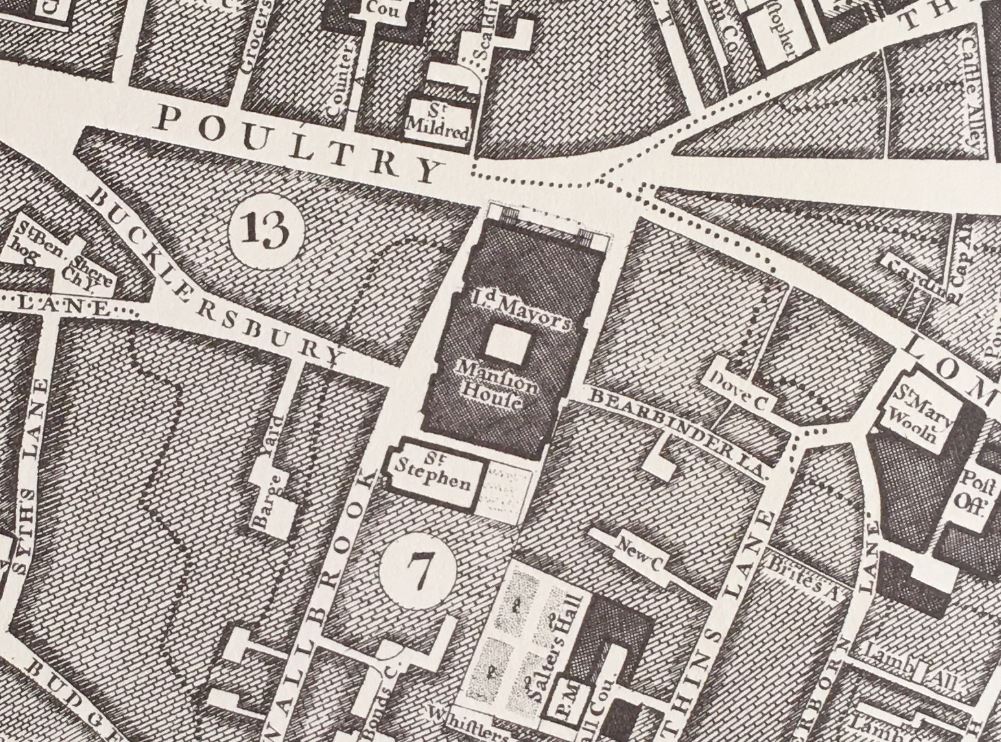

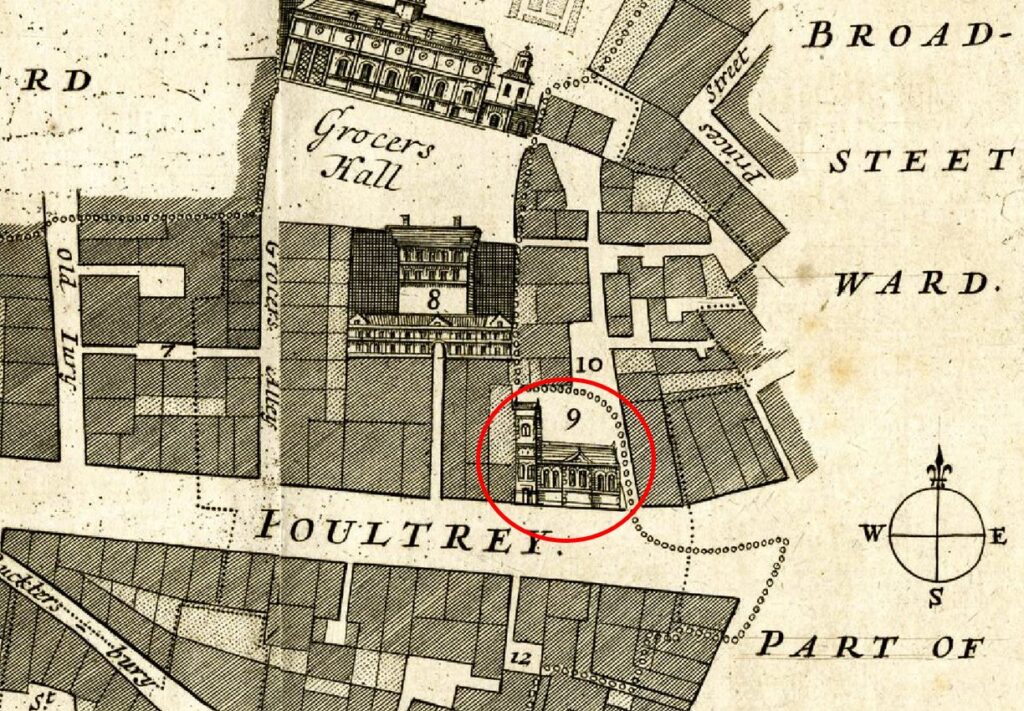

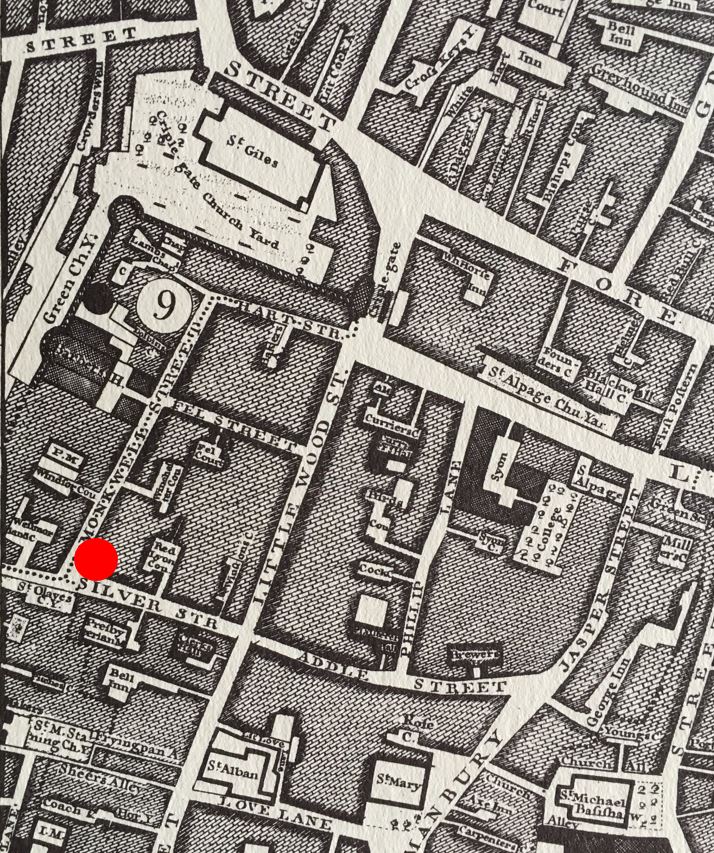

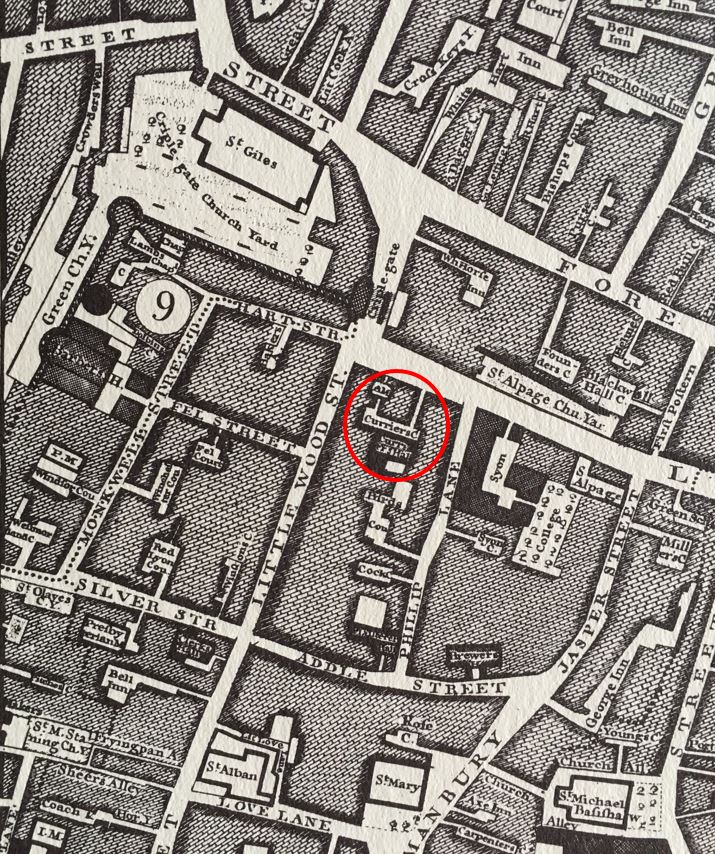

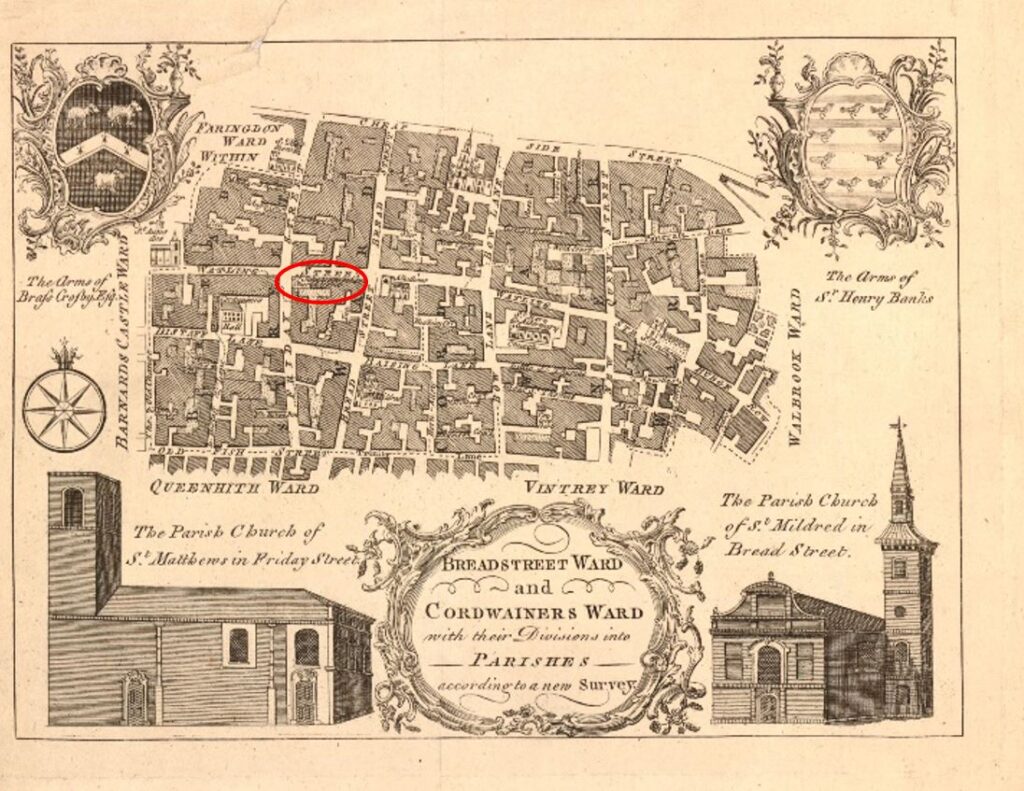

The location of the church was still marked in this 1772 Ward map of Breadstreet and Cordwainer’s Wards:

In the lower right corner of the above map is a view of St. Mildred’s, Bread Street. This was the church that was bombed during the last war, and from where the bust of Arthur Phillip was recovered from the ruins.

St. Paul’s School, Founded by Dean Colet

A very short walk to the west from the site of the above monument and plaque is the street New Change, and on the western side of this street is the following plaque, recording that St. Paul’s School, stood near the site of the plaque, from 1512 to 1884:

Although the plaque states 1512, there has been a school associated with the cathedral for many centuries before the 16th century.

Some form of school where those who sung in the cathedral were taught was probably in existance at some point after the cathedral’s founding in the early 7th century.

In the early 12th century, a Choir School was established where boy choristers were taught. The boys were typically those in need, and as well as being taught, the Choir School provided them with food and a place to live. The boys in the Choir School would have sung in the Cathedral.

As the school developed, two forms of education emerged. There was the Choir School and a Grammar School, the later concentrating less on the teaching of singing.

This is where Dean Collet comes in, and where the plaque may need a bit more detail for those casually looking at it.

Dean was not a first name. The plaque refers to John Colet who was Dean of St. Paul’s Cathedral. John Colet was the son of Sir Henry Colet, who had been the Lord Mayor of London for two terms.

On Sir Henry Colet’s death, John inherited a substantial fortune, and with part of this inheritance, endowed and refounded the Grammar School at St Paul’s.

Dean Collet’s refounding of the church is interesting as he seems to have taken a very “renaissance” approach to education and governance of the school.

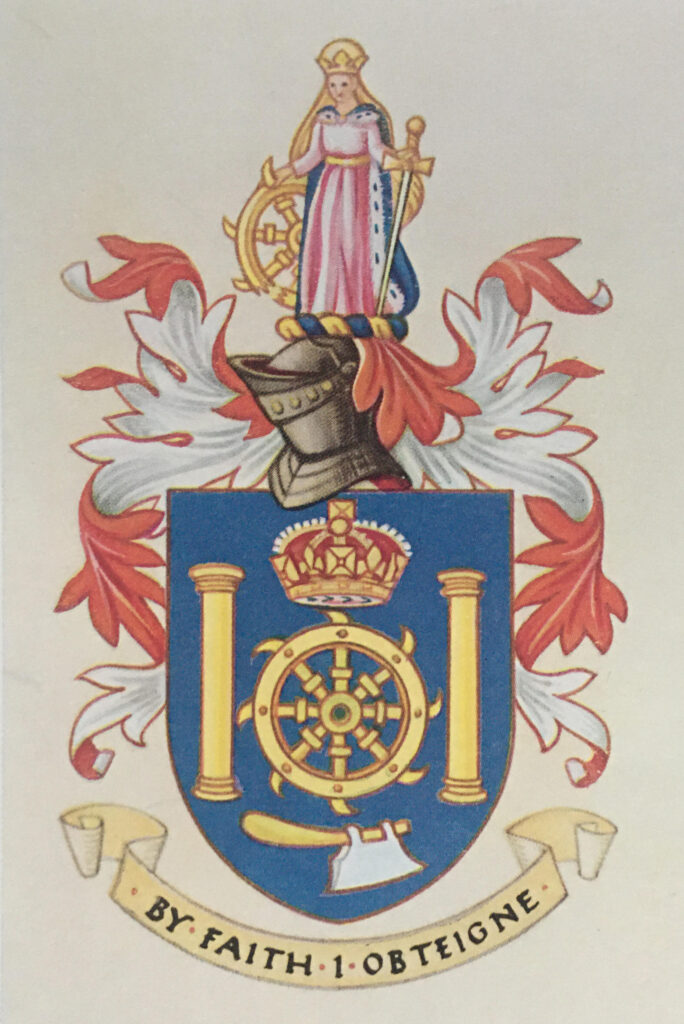

As would have been expected, education was based on Christian principles, but also employed a humanist approach. He also started a separation of the school from the Cathedral, as he chose members from “the most honest and faithful fellowship of the mercers of London” as school governors, rather than clergy from St. Pauls.

The choir and grammar schools continued to diverge and have separate premises, and today, the school founded by Dean Collect has been based in Barnes, West London since 1968.

The location of the plaque is shown in the following photo:

Although St. Paul’s School has moved to Barnes, the building where the plaque can be found is still as school, as the St. Paul’s Cathedral School, which is the school that the original Choir School has evolved into.

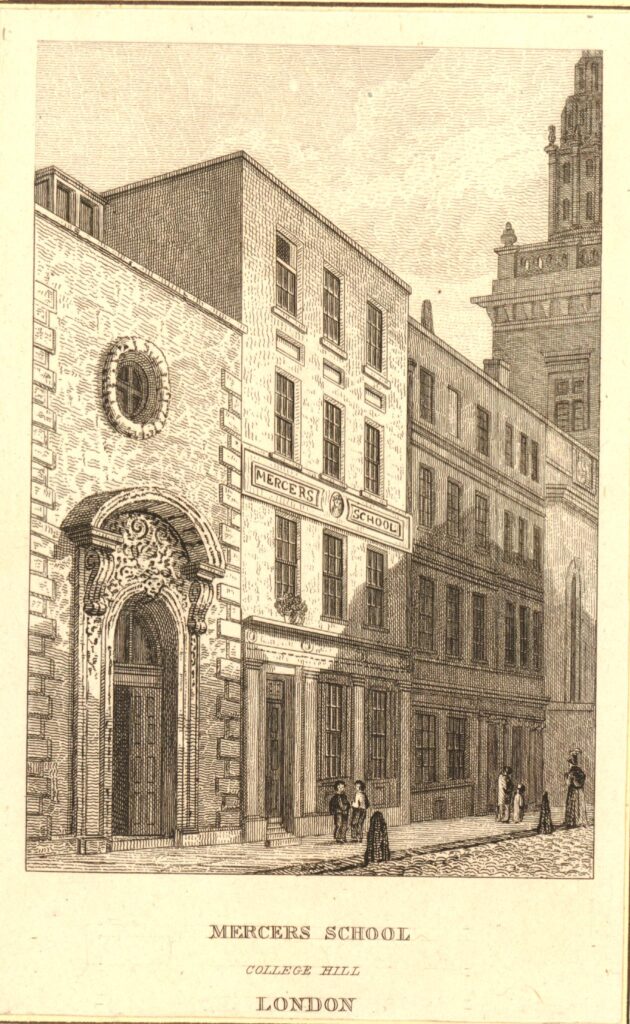

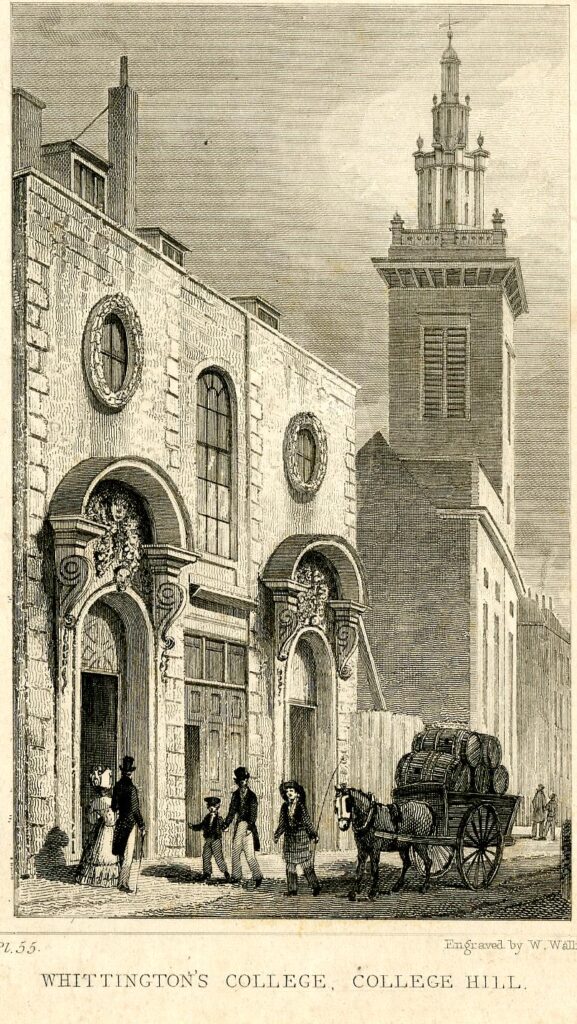

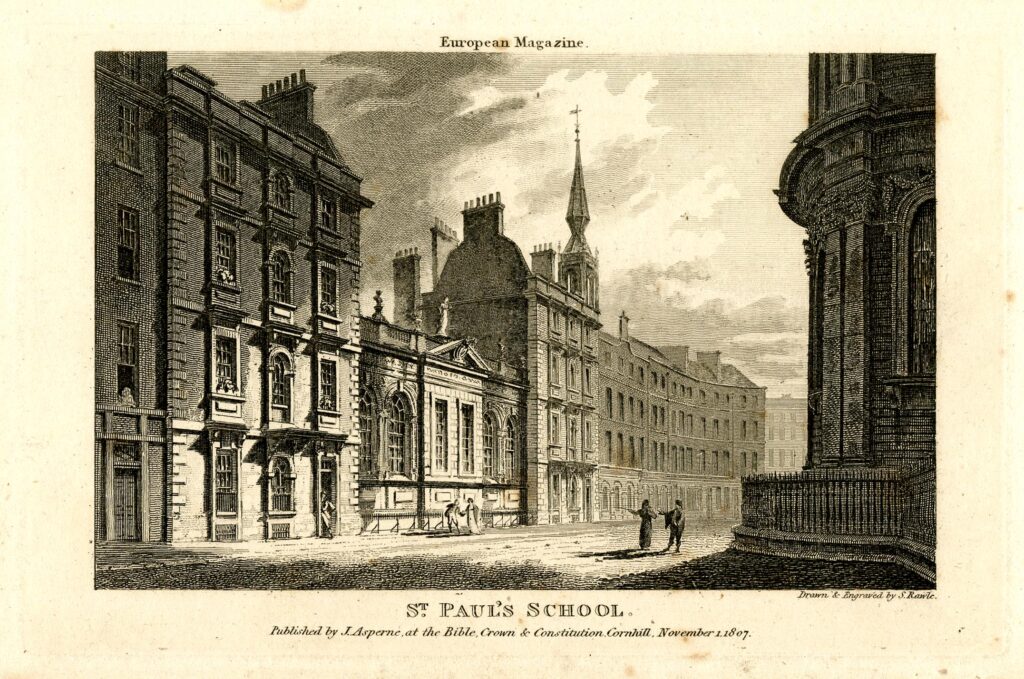

St. Paul’s School in 1807 is shown in the following print, looking across St. Paul’s Churchyard (part of the cathedral is on the right):

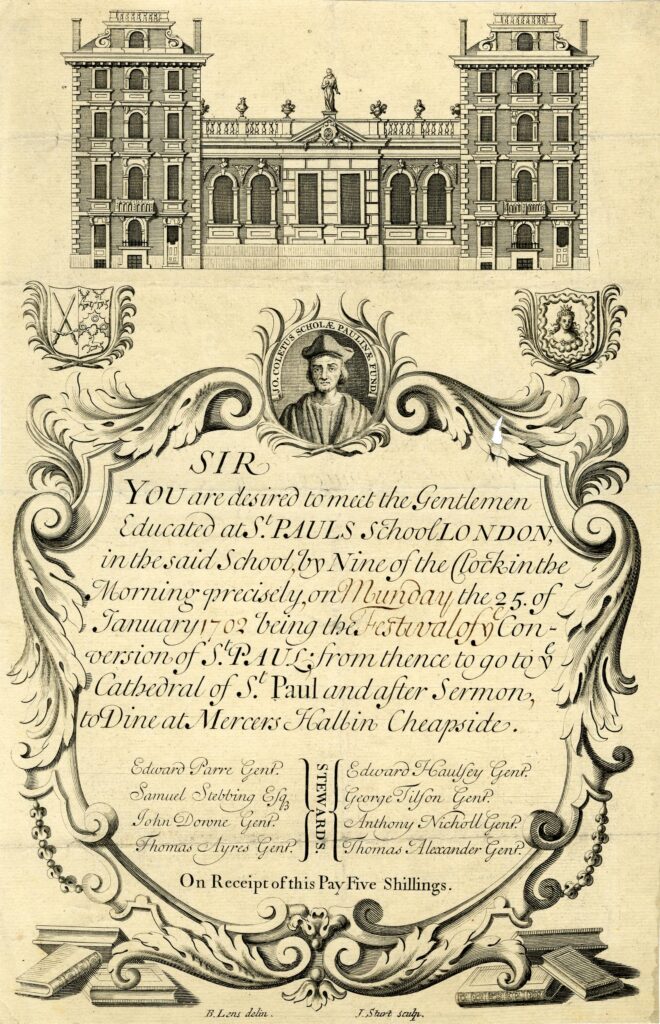

I believe that the school shown in the above photo is that founded by Dean Colet, as the following invitation to an event involving the school shows the same buildings, and the final part of the event is to “Dine at Mercers Hall in Cheapside”, and it was Dean Colet who employed members of the Mercers Company as Governors of the school ( © The Trustees of the British Museum):

Although Dean Colet’s school has moved to west London, the survival of a school on the site, associated with the Cathedral, is one of the places of centuries long continuity that can be found across the City.

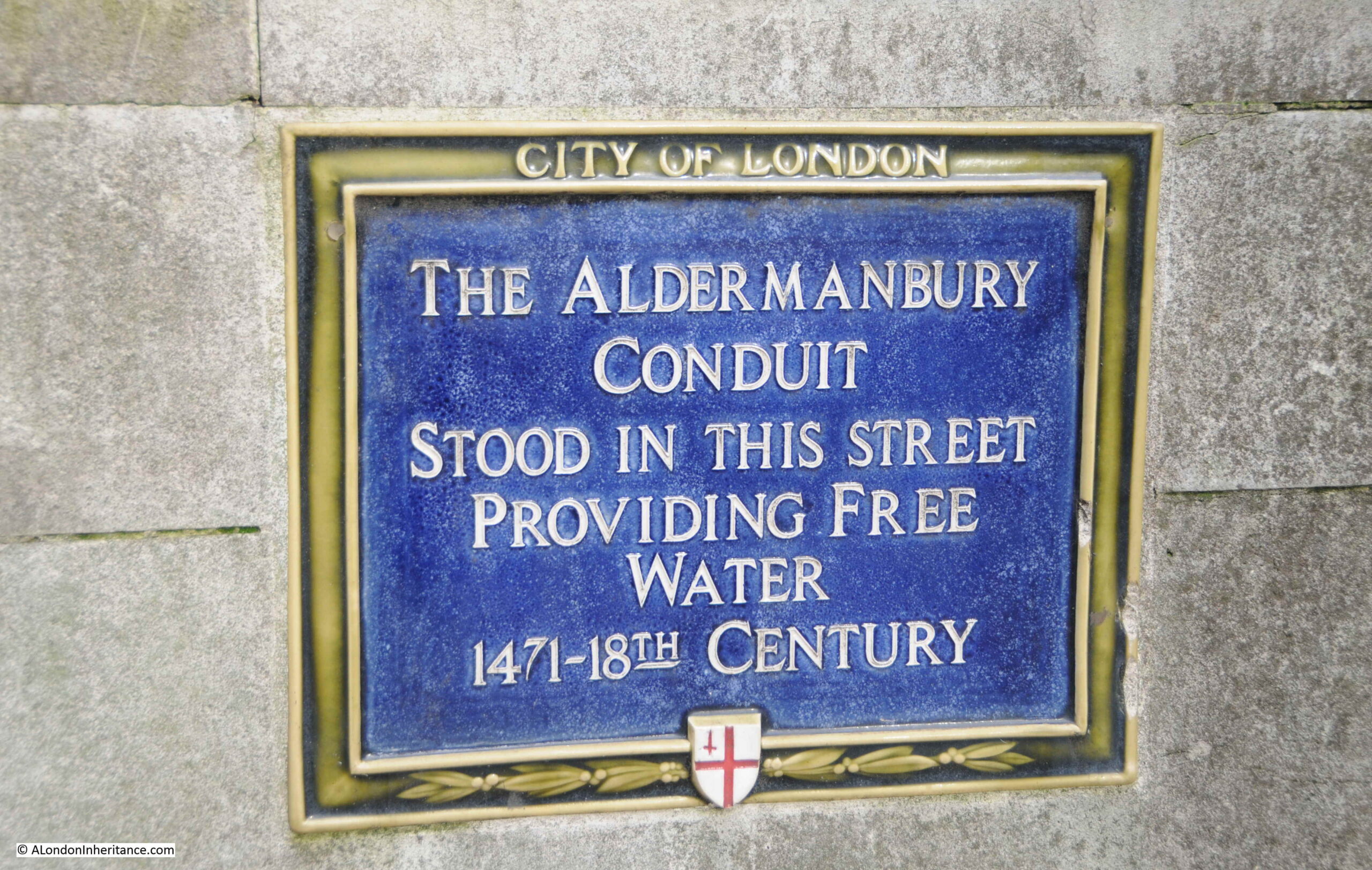

Water Fountain by the Company of Gardeners of London

If you walk from the location of the plaque to Dean Colet’s school, you will find to the south east of St. Paul’s Cathedral a grassed area, with fountains, surrounded by paving and seats:

Set into the surrounding wall is a plaque that records that the wall fountain was the gift of the “Master Wardens, Assistants and Commonality of the Company of Gardeners of London – 1951”.

The year of 1951 should offer a clue as to why the gardens are here. They were part of efforts to improve the post-war environment of the City, and their completion was timed to coordinate with the Festival of Britain, which is why they are called Festival Gardens.

The following photo shows the gardens soon after opening in 1951:

The street at the top of the above photo that runs to the right was St. Paul’s Churchyard, and this street, along with the circular feature at the very top of the photo, have since disappeared in the creation of gardens running along the south side of the cathedral.

Another street that has been lost is also recorded:

Site of Old Change – A City Street Dating From 1293

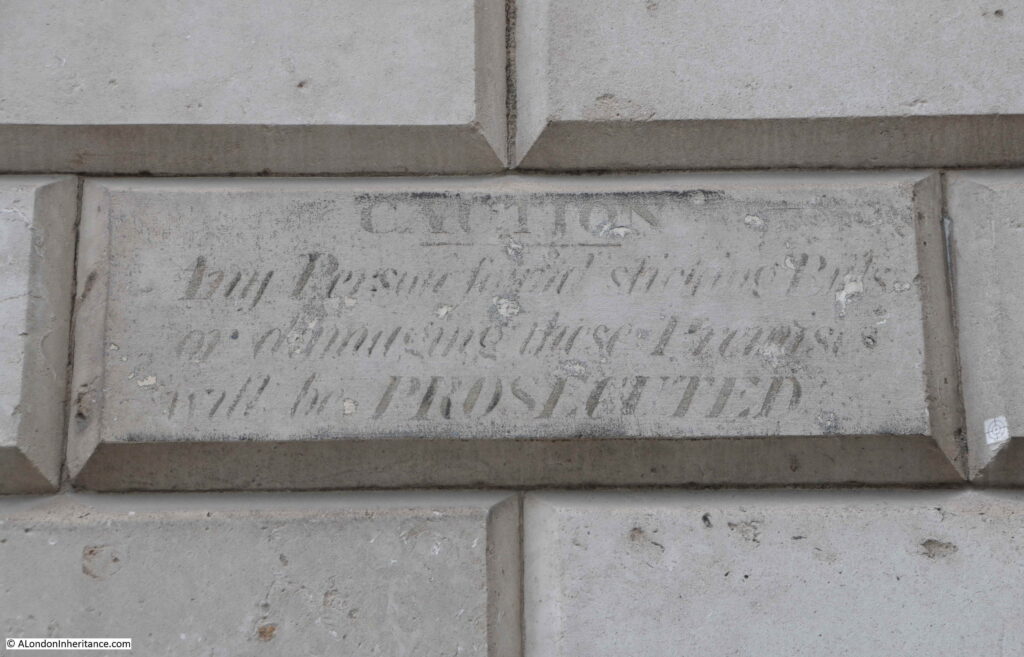

At the western end of the gardens is a wall, with fountains facing onto the grassed area. At the back of this wall there is a plaque on the northern corner of the wall:

The plaque records that this was the site of Old Change, a city street dating from 1293, and as you walk along the paved area to the side of the wall and plaque, in the lower right of the above photo, you are walking along part of the original route of Old Change:

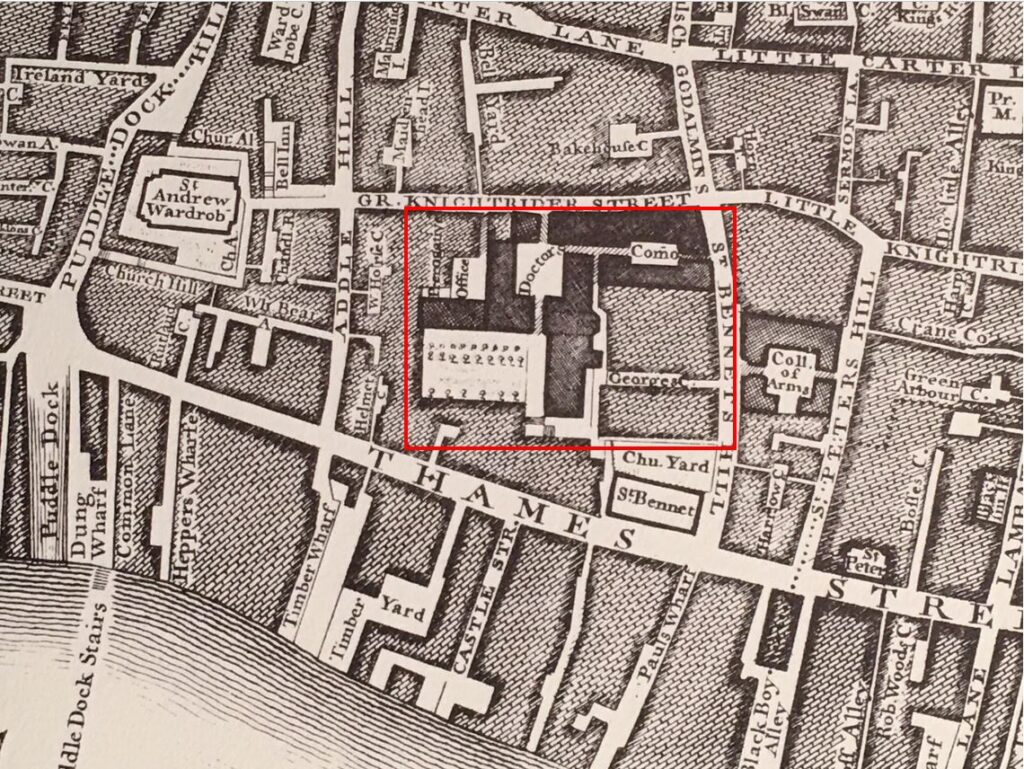

“London Past and Present” Henry Wheatley (1891), provides some historical background to the street, along with its original name, and the source of the name:

“Old Change, Cheapside to Knightrider Street, properly Old Exchange, but known by its present name since the early part of the 17th century.

Old Exchange, a street so called of the King’s Exchange there kept, which was for the receipt of bullion to be coined. Stow, p.129.

The celebrated Lord Herbert of Cherbury lived in the reign of James I, in a ‘house among the gardens near the Old Exchange’. At the beginning of the last century the place was chiefly inhabited by Armenian merchants. At present (1890) it is principally occupied by silk, woolen and Manchester warehousemen. On the west side were formerly St. Paul’s School and the church of St. Mary Magdalen, on the east is the church of St. Augustin.”

As I have mentioned before on the blog, it is always difficult to know what is really true. The above extract states that the name Old Change applied from the early part of the 17th century, however the reference to the street in “A Dictionary of London” by Henry Harben (1918) states that “First mention ‘Old Change’ 1292-4”, however Harben’s book does confirm the name Old Exchange also applied, and that the name came from the Kings Exchange, which was “situated in the middle of the street”.

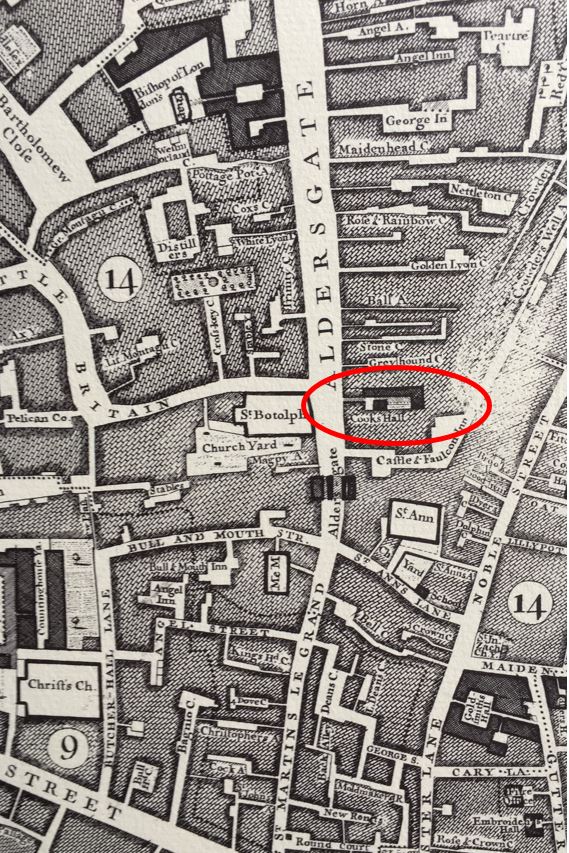

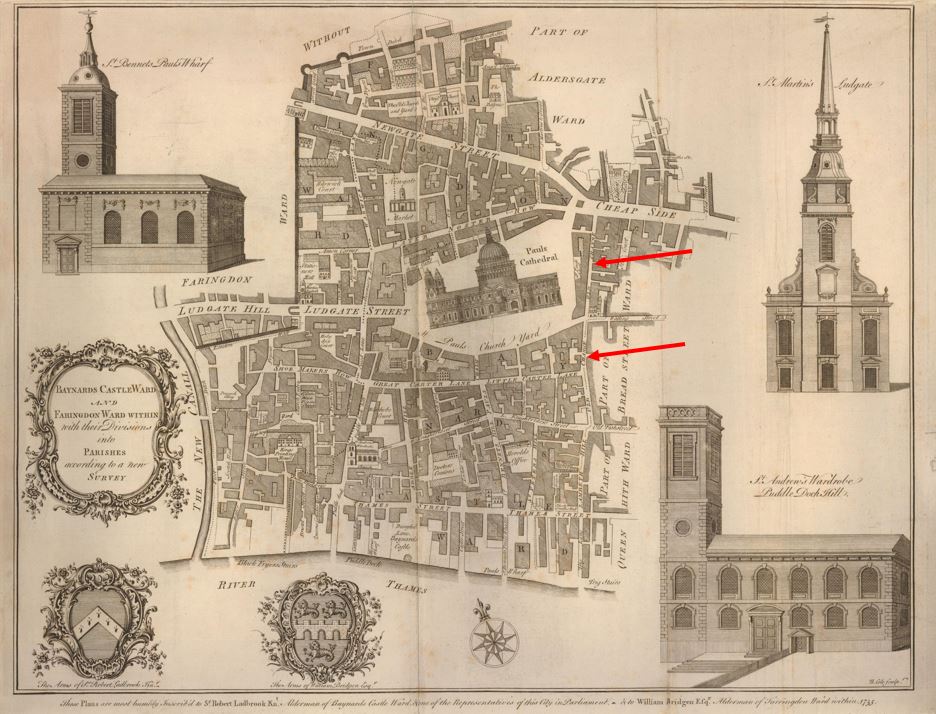

I have marked the location of Old Change in this ward map from 1755.

The uppermost red arrow shows the section from Watling Street to Cheapside, and the lower arrow shows the section from Watling Street down to the junction of Old Fish Street and Knightrider Street.

The map shows how built up the area immediately surrounding the cathedral was, and which lasted until the post-war development, which opened up some of the surroundings of the cathedral.

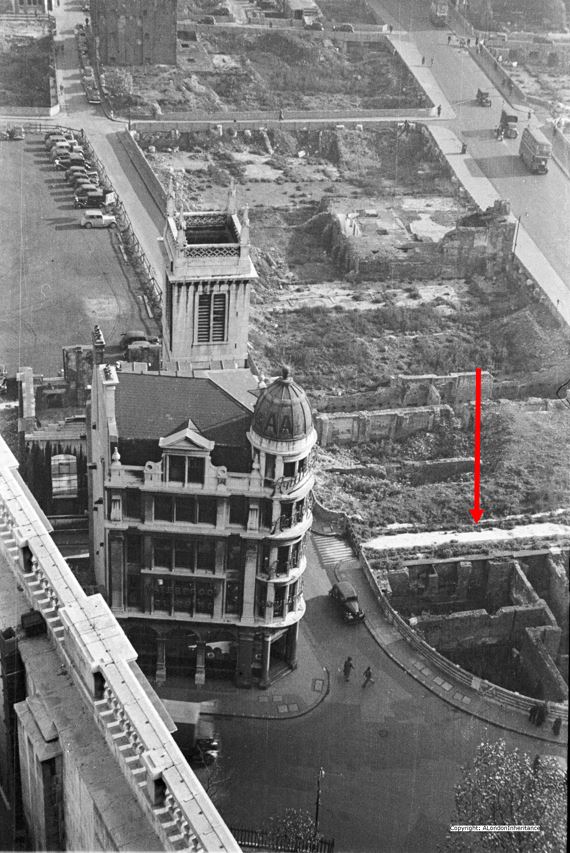

I have marked the location of Old Change in the following photo which is from my father’s series of post-war photos from the Stone Gallery of St. Paul’s Cathedral:

The wall at the back of the fountain on which the plaque is mounted is along the side of the street at the position of the arrow head in the above photo.

The plaques and monuments to be found across the City of London tell some remarkable stories of the City’s history, and of those who were born and have lived in the City.

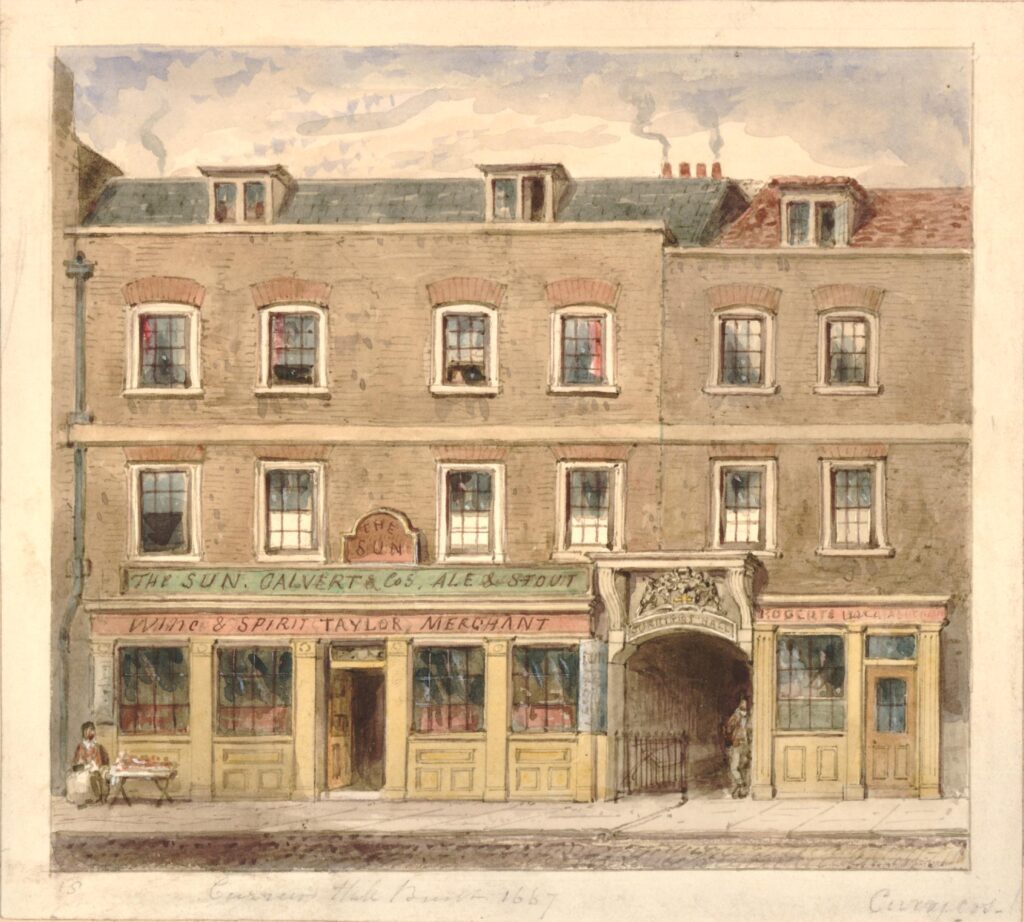

Well worth more than a quick glance when walking the City’s streets.