Before exploring Alderman Stairs, a quick thanks for all the feedback to last week’s post regarding the statue in Catherine Place – I will be updating the post with some of the additional information and possibilities as to the meaning of the statue.

I was recently walking along St. Katherine’s Way, heading towards Thomas More Street to find the location of one of my father’s photo. I walked by Alderman Stairs, and as the tide was out, as I have many times before, I walked down to the foreshore.

I find the river stairs that remain fascinating. They provide a connection between the land and the river, and are a reminder of when the river was a bustling place of trade and passenger transport.

Today, they are frequently quiet. I very rarely see anyone else on the foreshore at Alderman Stairs.

It is interesting to imagine everything that has happened over the centuries, centered around these stairs – all the people who have arrived or departed, everything that has happened in the Thames adjacent to the stairs.

I thought it would be interesting to research back through newspaper articles for references to Alderman Stairs, and use these to tell the story of Life and Death at Alderman Stairs.

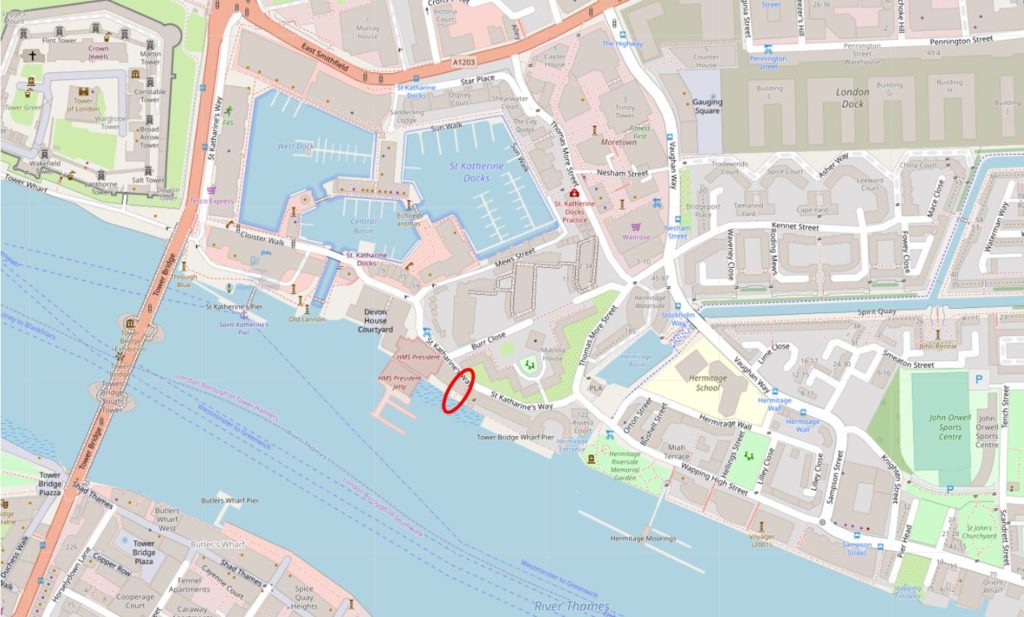

Alderman Stairs are along St. Katherine’s Way, just east of what were St. Katherine Docks. I have marked the location of the stairs with a red oval in the following map (© OpenStreetMap contributors) :

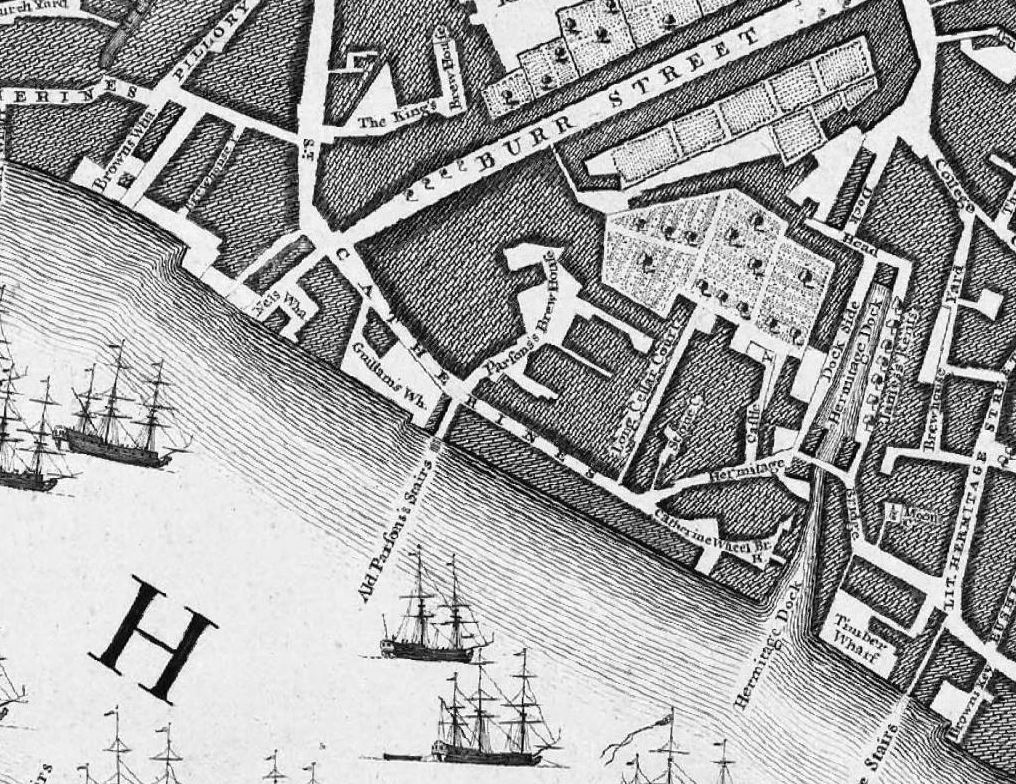

The stairs are old. Henry Harben in A Dictionary of London states that the first mention of the stairs was by John Rocque in 1746. The stairs had a number of names, including Alderman Stairs, Alderman Parsons Stairs and Lady Parson’s Stairs.

The name possibly derives from a former owner, Sir John Parsons who was an Alderman of Portsoken Ward in 1687. There are also references to Humphrey Parsons, Alderman between 1721 and 1741, and Sir John Parsons, Fishmonger described as the son of Parsons of St. Katherine’s.

Although I have seen references to Alderman Parsons Stairs in newspaper reports, the majority of references are just to Alderman Stairs, so over time the name was probably abbreviated down to the form we see today.

John Rocque’s map of 1746 shows Alderman Parsons’s Stairs leading down into the river from what looks to be Catherine Street, with Parsons’s Brew House across the street.

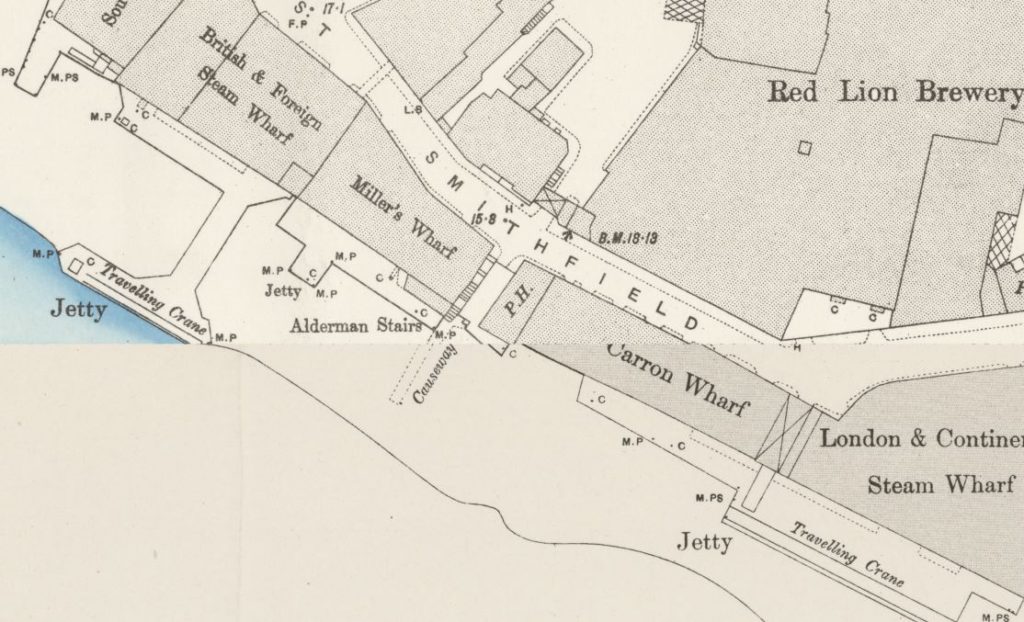

Catherine Street is today St. Katherine’s Way, but between these two names it was also called Lower East Smithfield (see the 1895 OS extract later in the post).

Walking between the two high buildings on either side, through to Alderman Stairs:

Alderman Stairs is just a single place in the whole of London, and based on my visits, the stairs and foreshore do not receive many other visitors, however exploring what happened here can tell us so much about life in London and life on the River Thames.

So here is a sample of Life and Death at Alderman Stairs.

The river has always been a dangerous place, but the sheer number of deaths in and along the river and the apparent casual acceptance in the way these are reported is remarkable from a 21st century viewpoint.

The Illustrated London News on the 7th June 1851 reports on one single day on the River Thames, including Alderman Stairs:

“FATAL RIVER ACCIDENTS – On Tuesday, Captain Artus, of the brig Melbourne, lying in Bugsby’s Hole, in attempting to ascend the side, missed his hold, fell into the water, and was drowned. Almost at the same time, (twelve o’clock), Captain Downie, of the ship mentor, lying off Stone-stairs, Wapping, fell overboard and perished. About 3 o’clock, P.M. a boat, containing two men and a woman, was swamped near Alderman Stairs; the men were saved, but the female, Mrs Coghlan, residing in Old Gravel-lane, was drowned.”

That is three deaths in one single day.

On the 5th November 1842:

“FATAL ACCIDENT – Tuesday night, a few minutes before twelve, John Dunlevy, cook on board the steam-packet City of Limerick, lying off the Alderman’s-stairs, Lower East Smithfield, while proceeding on board the steamer, and having just effected a landing on the accommodation ladder, fell into the river, and was carried away by the strong flood tide at the time, and was drowned. He was partially intoxicated. the body has not been found.”

On the 10th September 1842:

“On Saturday morning a large sailing barge, navigated by two men and a boy, while coming up the river, was sunk by the heavy swell caused by several vessels going down the river at full speed. She went down nearly opposite the St. Katherine Dock entrance. The people in her were saved by the watermen, who rowed from Alderman’s Stairs to their assistance. The barge was laden with 70 tons of coal. The damage sustained is estimated at £300.”

A report in the Illustrated Police News dated the 10th October 1903 highlights the risks that waterman working from Alderman Stairs endured when crossing the river:

“NEARLY DROWNED – AN EXCITING SCENE ON THE THAMES. At the Southwark County Court his Honour Judge Addison and a jury heard an action in which Henry George Wilson, an aged waterman, sought to recover damages from Arthur Gamman, of Holborn Wharf, Chatham, for personal injuries sustained.

Plaintiff said that on April 17 he was rowing his boat across from Alderman Stairs to Mills Stairs, Bermondsey, when he saw a steam hoy nearly on top of him. Without a word of warning from those on board she came on, and catching his boat amidships, smashed her to pieces, going right over the wreckage. He went under her and was much scratched and bruised. On rising to the surface almost exhausted he heard a cry of ‘Strike out Harry, there’s a boat coming’. Being a cold day he was heavily clad and sinking when somebody clutched him, and he eventually found himself being brought round on a ship.

Mr Thompson said it was only fair to the captain of the hoy to say that when he saw what had happened he very gallantly jumped overboard in his full rig and secured Wilson just as he was going down.

Charles Wady, the captain, said he signaled to Wilson to stop rowing. He did so, but started again, and witness could not stop in time to avoid the boat. When he saw Wilson go under the hoy he stopped the screw, which was reversing, fearing that he would be cut up.

His Honour warmly complimented Wady on his plucky behaviour.

The jury found in favour of the plaintiff, awarding him £25, for which amount and costs judgement was entered.”

I took the following photo from the top of Alderman Stairs, looking down to the river. Fortunately the tide was out.

In the introduction to the post, I mentioned that the stairs were also called Lady Parsons’s Stairs. The use of the Parsons name in the name of the stairs is mainly concentrated in the first half of the 19th century and earlier. A typical example is from this report in the Morning Chronicle of the 12th February 1818:

“Yesterday morning the body of a young woman, apparently about 21 years of age, was found by a waterman, who was rowing near Lady Parsons stairs, in the river Thames, lying in the mud near the stairs.”

Another reference to Parsons’s Stairs records one of the very many tragic stories of those found in the river. From the London Courier and Evening Gazette on the 1st August 1801:

“Thursday night, about eight o’clock, was found floating in the Thames, at Parsons’s stairs, the body of a young woman, and brought to Aldgate Workhouse, Nightingale-lane. She was decently dressed in a cotton gown, brown ground, with white running sprig and leaf, modern pattern; a cambric sprig-netted shawl; had only one pocket on, in which there was nothing but one glove and tie, and a white pocket handkerchief. She appears to have been drowned upwards of a week, and appears to be about 20 or 30 years of age.”

The Parsons name also comes up in a reference to a possible bridge across the Thames before Tower Bridge was built. The Morning Advertiser of the 30th March 1824 listed petitions being presented at the House of Commons. One of these was:

“Mr T. Wilson presented Petitions from Watermen of St. Katherine’s Stairs, Old Parson’s Stairs, and the Tower Stairs, against the St. Katherine’s Suspension Bridge Bill.”

The St. Katherine’s Suspension bridge was a proposal for a bridge to improve access between St Katherine’s Dock and the proposed South London Docks. There were many objections to the bridge, including from the City of London. The bridge was not built.

There has always been immigration into London and on the 24th April 1847, the Illustrated London News reported on arrivals at Alderman Stairs:

” IRISH IMMIGRATION INTO LONDON – The importation of Irish paupers, so much complained of in Liverpool and Glasgow, begins to wear a threatening aspect in London. On Sunday, the Prussian Eagle, from Cork, and the Limerick, from Dublin, landed 1200 Irish Paupers at Alderman’s Stairs, Lower East Smithfield. The new comers, who were in the most wretched state of distress, were forthwith distributed over the eastern part of the metropolis. The same vessels landed 1200 Irish paupers on Sunday week.”

After walking down the stairs, I crossed over onto the foreshore. The following photo is looking to the west. The stones of the stairs running into the Thames.

The pier of HMS President the Royal Naval Reserve unit associated with London is adjacent to Alderman Stairs.

If you look at old maps of east London, along the River Thames, adjacent to many of the river stairs was a public house. Probably this should not be a surprise as being next to where people were boarding or arriving on ships, was a good place to attract trade.

Sailors or passengers arriving after a long journey would probably welcome a quick stay in a pub after arriving onshore.

Adjacent to Alderman Stairs was the Cock and Lion public house, The pub had been next to the stairs from the 18th century to some point in the 1920s when it was demolished.

It is shown in the following extract from the 1895 Ordnance Survey map, just to the right of Alderman Stairs:

Credit: ‘Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland’

The pub is mentioned in a number of articles, including the Public Ledger and Daily Advertiser, dated the 1st September 1832, where a sailor, his shipmate and two women landed at Alderman Stairs from the Amity passage vessel and went straight into the Cock and Lion public house.

It was when he was in the pub that the sailor found his pocket book was missing, and accused the two women of stealing it.

One of the women asked a waterman to then row them across to the Europa Tavern at Rotherhithe, where one of the women asked the landlord to change a £5 note. Suspecting that this had been stolen from the sailor, the waterman snatched the £5 note, and both women were taken into custody.

This report, along with so many others highlight a way in which we see the north and south banks of the river has changed.

Today, the north and south banks are considered part of north and south London and therefore different. Reading books and newspapers from the 18th and 19th centuries, this separation was not that apparent – north and south banks were seen as part of the river environment rather than as different parts of London.

Numerous reports of events at Alderman Stairs, include casual crossings of the river, as in the example above, where it was probably thought very normal to cross the river from a pub on the north, to a pub on the south bank – all part of the same river ecosystem.

The river was full, not only with passenger and cargo ships, but also with waterman, the river based taxi services of the time, offering quick transport across and along the river.

Not so easy today, however a couple of Saturday’s ago I was in the Gun on the Isle of Dogs for late afternoon, followed by the Angel at Rotherhithe for the evening. Rather than a waterman, the Jubilee Line provided cross river transport between the two.

The following photo shows the view looking east. The pier extending into the river is where the Thames pathway returns to the water edge.

The boats in the river are at Hermitage Moorings.

Alderman Stairs were a reference point for the ships mooring in the river, and there are many records of the arrivals by the stairs.

From the Illustrated London News on the 23rd December 1843:

“CHRISTMAS FARE – On Sunday night the Dublin Steam Navigation Company’s steam-packet Royal William, Captain Swainson, arrived at her moorings off the Alderman-stairs, Lower East Smithfield from Dublin, Falmouth and Plymouth. She brought a miscellaneous cargo, part of which consisted of a large quantity of geese, turkeys, and other Christmas fare, for the metropolitan markets. In the course of Saturday and Sunday a number of steam-packets arrived in the river with large quantities of geese, turkeys, and other kinds of poultry, for Christmas cheer. Last week, several vessels arrived at Fresh-wharf, London-bridge with cargoes of varied fruits. Most of the stage-coaches which arrived in the metropolis on Tuesday and during the week brought very large quantities of geese, turkeys, hares, &c.”

The following photo shows the view looking back from the bottom of Alderman Stairs:

The stairs consist of the steps up to street level and a paved stretch along the foreshore that runs into the river. This paved stretched raises the stairs above the foreshore to provide a flat walkway and without the mud, sand and random debris that litters the foreshore.

Alderman Stairs were also a departure point for regular shipping routes for both passengers and parcels. Departures and routes were regularly advertised in the newspapers, for example, in the Shipping and Mercantile Gazette on the 18th April 1838, the St. George Steam Packet Company were advertising that:

“Vessels sail regularly from off Alderman-stairs, below the Tower for:

PLYMOUTH, FALMOUTH and CORK, and taking goods and passengers for Liverpool, every Saturday morning at 8 o’clock.

EXETER, calling off Deal, Ryde and Cowes (weather permitting), every Wednesday morning, at 8 o’clock.

BOSTON – The SCOTIA, on Tuesday morning, the 10th April , at 4 o’clock, and every succeeding Tuesday at the same hour.

STOCKTON (at reduced fares), calling off Scarborough and Whitby, weather permitting – The EMERALD ISLE, every Saturday night at 12 o’clock, returning every Wednesday.

Goods to be sent to the St. George Steam-wharf, Lower East Smithfield.”

Passengers arriving off Alderman Stairs ran the risk of being overcharged for their transport between ship and shore, as this article from the Morning Post on the 29th September 1847 reports:

“MONSTROUS OVERCHARGE BY A WATERMAN – Yesterday, John Thomas Jones, a waterman, appeared before Mr Yardley, to answer the complaint of Mr. Edward Sole Munico, wine merchant of Trinity-square, for making the following grievous overcharge.

On Sunday the 29th of August, Mr Munico, a lady, and a gentleman, were passengers in the AJAX, a Cork steamer, which arrived that day off the Alderman’s Stairs, Lower East Smithfield. After the vessel was moored, the defendant, who was in his boat alongside, came on board, and was engaged by Mr. Munico to convey him and his friends and luggage which consisted of seven packages not exceeding five cwt, to the Alderman’s Stairs exactly opposite. The party was no sooner afloat that the defendant, who had a partner with him, said he could not land his fare at the Alderman’s Stairs, but would row to the Tower Stairs, or any other place. Mr. Munico then directed him to row to the Dublin Wharf, adjoining the Alderman’s Stairs, where the complainant wished to deposit some of his luggage, intended to be shipped to India. No landing could be effected at Dublin Wharf because it was a Sunday, and the boat was rowed into Alderman’s Stairs, where the defendant demanded 12s 6d as his fare, and would not allow Mr. Munico and his friends to land till it was paid. Mr. Munico expostulated with him for some time, but with little effect; at last he reduced his claim to 8s 6d, which was paid to him and the passengers and luggage were landed. the utmost that the defendant was entitled to claim was 3d per each passenger only, and they were entitled to carry 56lbs weight of luggage each. Beyond that the quantity the waterman was entitled to charge 1s per cwt, which would make the total amount of his fare only 4s 3d.”

The report then states that the waterman had no right to ply on a Sabbath between the steamer and Alderman’s Stairs, as that privilege belonged to the Sunday ferrymen, who rented it off the Watermen’s Company. The defendant was fined 20s, however Mr. Munico interceded on behalf of the waterman, on which the penalty was reduced to 10s and costs.

A lesson which also applies today, to agree a fare before getting into a river boat, or a taxi.

A report in the Evening Chronicle on the 30th October 1840 also highlights the risk to travelers arriving in London by Alderman Stairs.

The report was about another waterman, a certain William Vallance, who was a member of the ‘Jacob-street gang of steam boat rangers’. In the reported case, Vallance had been directed to meet the Dublin steam-ships when they arrived off Alderman Stairs, however the members of the Jacobs Street gang would persuade their passengers to be taken to another landing point where they could be charged significantly more. The Jacob Street gang would also “on arrival of a steam ship the Jacob-street gang managed to board the vessel while the crew were busily engaged in mooring the vessel, and seized any luggage they could lay their hands on, which they lowered into a boat, generally having a fellow of very questionable character ready to receive it and stow it away”.

Theft of goods from the ships moored on the Thames and from the warehouses that lined the river was a continuous problem, and had led to the formation of the Thames River Police,

The Thames river Police would frequently question people carrying goods along the river, on land, or at the river stairs. If they could not give a satisfactory explanation for why they were in possession of the goods, they would be arrested for theft. Newspapers often carried long lists of those arrested, and the goods they were found with. On the 3rd September 1821, the Public Ledger and Daily Advertiser included a “E. Bateman who was found with 1lb of sugar at Alderman Stairs” without being able to give any satisfactory explanation of why he was in possession of the sugar.

The remains of old piers can still be seen:

Ships moored off Alderman Stairs could also be purchased. On the 12th of January 1809, you could have bought the “good Brig LITTLE WILLIAM, square stern, foreign built, and free; burthen 84 tons per register, is abundantly found in good stores, and can be sent to sea at a very trifling expense; is well adapted for the Mediterranean or any other Trade her burthen may suit. Now lying off Alderman’s-stairs, John Gofton, Master.”

The view looking west, under the decked area in frount of the converted warehouse to the west of Alderman Stairs:

Reports involving Alderman Stairs also highlighted the dangers of passenger shipping, for example this article from the Evening Chronicle on the 17th October 1838:

“DREADFUL STEAM-PACKET COLLISION – The non-arrival of the Dublin Steam Packet Company’s vessel Shannon, Captain Pym, at her mooring of the St. Katherine’s Dock, on Sunday, or yesterday morning from Dublin, Falmouth and Plymouth, excited considerable apprehensions for her safety,and that of the passengers and crew.

These fears were still more heightened, owing to the recent heavy gales which she must have encountered at sea; and in consequence of information having been received at the company’s office, St. John’s-street, Minories, by yesterday morning’s mail, from Portsmouth, that the steam-ship Thames, Captain Williams, belonging to the same company, which sailed from the river for Dublin on Saturday morning last, with a great number of passengers, had put into that port (Portsmouth) early on Sunday morning, with extensive damage, having been in violent contact with a large steam-vessel off Brighton, about twelve o-clock on Saturday night. When the collision took place both vessels were proceeding at full speed, although the night was dark and stormy.

As might be expected, the consternation among the passengers most of whom were in their berths, was frightful in the extreme – doubtless rendered the more so on account of the recent dreadful loss of the Forfarshire, and other steam packet disasters. The steam-ship with which the Thames was in collision was believed to be the Shannon, from Dublin for London, although this could not be correctly ascertained, the steamer having proceeded on her voyage, and not again seen.

These particulars were received in the city by the Portsmouth mail yesterday morning, and soon spread through the metropolis to the distress of those who expected relatives or friends to be on board, the Shannon not having at that time arrived; and the belief in consequence being entertained that after the collision with the Thames she had gone down with all on board.

Yesterday, soon after noon, these evil forebodings were happily dispelled; the Shannon having arrived at her moorings off the Alderman-stairs, Lower East Smithfield.”

A final look back up the stairs:

These stairs are so quiet today. There are no waterman rowing their passengers across the river. Sea going passenger and cargo ships no longer travel this far up the river (apart from the cruise ships berthing alongside HMS Belfast), but stand on the Thames foreshore, look up the stairs, and imagine the countless thousands of people who have used Alderman Stairs as their gateway to the river.

Fascinating, thank you. It is a wonderful reflection of the moments in countless lives (and deaths) taking place on and near the unassuming little stairway to the water, over hundreds of years.

I was particularly struck by the plight of the 1200 ‘Irish paupers’ (desperate to escape the Potato Famine?) and hope that London was kind to them.

Absolutely fascinating article, as always. So much information, I could spend the rest of the day clicking on links and exploring the surrounding areas by internet! As you say/write, so much has taken place on this landing, so many pairs of feet on those stones.

By pure coincidence happened across Alderman Stairs last week and took a walk down. I used to live in the Isle of Dogs in the the late 70s so walked along the north bank area for the first time in at least 40 years. How it’s changed even in my lifetime. Recommend the Dockland’s Museum for reminding us how London has changed and always changes.

Another fascinating post with really interesting stories. The comments reported at the time in the press about the “Irish paupers” are similar to those often heard in relation to eastern Europeans during the Brexit campaign. Some of these paupers may well have been involved in the construction of some of the docks to the east of Wapping and other infrastructure in London and beyond. I grew up in Wapping and there were two distinct groupings of Cof E and Roman Catholic people who attended separate churches and schools but lived side-by-side fairly happily.

Thank you again

Love these posts.

I am descended from the Wilson`s who were watermen and lived in Wapping.

Couldn`t unerstand how my ancestor Archibald Wilson born late 1700`s a mariner from Plymouth ended up in the East End of london but see a steam packet ran from Plymouth at one time….Question solved perhaps ??

Been there many times but unaware of the importance of the level of migration to London in particular, great stuff.

Another extremely interesting post. Thank you.

It is amazing that such an innocuous set of steps should be associated with such a rich history of both life and death.

Very interesting article, with the well told stories from the papers of the times.

Yet another interesting piece on London history. If only the Alderman Stairs could talk……………………………….

Very interesting. Many thanks for the post. Your pictures capture so well the contrast between the tidy modern entrance and the slime-covered foreshore, which invites thoughts of the past. I have been estimating the risks of death when boarding vessels in modern ports, so the accounts of life and death on the stairs are intriguing. I wonder how many people would have used the stairs, especially before Tower Bridge? The mention of 1200 in one shipload suggests it could have been as busy as Tower Bridge is today. Did you notice in your research any estimate of how many people would have landed on or departed from the stairs on an average day?

In my ancestor’s travel journal from 1852, he too reports a porter who was unloading s steamship missing his footing and falling into the river – in this case the Mississippi, under the ship’s screw and not surfacing again. Working life was dangerous in the 18th century.

my gg uncle ewings groat drowned off st katherines docks.he sighned on in the navy in 1861.

he lived in portsea island portsmouth.i would like to know if he drowned in 1861. he was born 1832 wick scotland; any help i appreciate thank you

barbara.

I just came across this article doing some research for a book. Wonderful website!! This reminds me of a hunt for the Old Wapping Stairs that was sparked off by a photo my husband and I were looking at which was hanging up at the 72nd Street Pub in Seattle. We looked at that, noticed The Town of Ramsgate pub, and next time we were staying in London, went off in search of it. No other reason but curiosity. I carried with me my Georgian A to Z (Rocque’s map) for a ‘now and then’ look. We had a pint at the pub, then sat on the stairs and looked out onto the river. It was a quiet ‘soft’ day, and we saw a few people mudlarking on the bank of the Thames at low tide (which I do when I can).

This is very interesting. My 4gts-uncle was the licenced victualler at the ‘Black Boy’ pub – no 88 Lower East Smithfield …….. so just a few metres east of the stairs – between 1861 and 1866. I imagine he used these steps frequently.

I came across this location from an Instagram post on hidden places in London. Then for fairly obvious reasons, (my surname!) I looked it up further on line and came across this article. Absolutely fascinating tales of a time long past (Somehow some traits still go on, thieves and unscrupulous transport operators over charging but thankfully the world of shipping is much safer now.) I live in London and have been close to this spot previously totally unaware. We shall visit at some stage and imagine the past that has been so brilliantly detailed in this article. Thank you.

A footnote..

of course the 1200 Irish immigrants is the most startling reminder of how things haven’t changed in today’s world. And the nature of their crossings can’t be deemed to be safer either. Apologies for this previous ommission.

Thanks for this fascinating piece. I’m always intrigued by how people (who needed to) got around the country before the railways were built and roads improved. Of course there were stage coach services but the idea of packet ships taking passengers along the coast to and from the North and the South West was one I hadn’t considered. I wonder what the relative costs were.

I have been particularly interested in your references to the Cock & Lion Public House adjacent to the stairs until the 1920s. My 2nd. great grandfather, William Scull is listed as the Licensee for the Cock & Lion from 1848 to 1860 and the 1851 census would indicate that William (53), Maria (46), eight children and one grandchild were resident over this period. Family occupations revolved around victualling and shipping and included shipping clerk, merchant seamen and lighterman occupations. It is interesting to contemplate William’s life and times and your article helps paint an increasingly vivid picture played out beside the Thames and under the shadow of the Tower of London. Would be great to have a pint with William and delve into the tough and shadowy side of dock life and press ganging etc.

I stumbled upon the Stairs randomly while roaming London on a visit. It is such a a tiny and lonely place, blink and you miss it– I had no idea it was so laden with history and impact.

I visited during high tide, apparently, and saw mysterious steps just leading into the dark water. But your words and images brought them to life for me. Wonderful article.