The London County Council (LCC) along with the metropolitan boroughs, transformed London.

The LCC was responsible for the coordination and provision of a wide range of services across London, for example the growth of council provided housing, education, provision of medical services, parks and gardens, infrastructure and consumer services. The LCC, along with authorities such as the Metropolitan Water Board, the London Passenger Transport Board, the London Fire Brigade and the Metropolitan Borough Councils transformed London from the 19th century city to the city we recognise today.

The London County Council produced a considerable number of publications on almost any aspect of the running and organisation of a major city that you could imagine. Within these publications there is a common theme – a considerable pride in the city and the services that the LCC provided to Londoners.

Much of this can look strange from a 21st century viewpoint – too intrusive, too organising, too much “authority knows best”. However with austerity, drastic reductions in council services, library closures, funding challenges for the NHS, Police and Education, the past can look deceptively attractive, but dig deeper and comparisons are never simple.

I have collected a wide range of LCC publications over the years, they provide considerable insight into the development of the city from the formation of the LCC in 1889 until the transfer to the Greater London Council in 1965.

For this week’s post, I would like to feature a publication which provides an overview of all the services provided by the LCC and other London authorities. A snapshot in one specific year – 1937.

This is London In Pictures – Municipal London Illustrated.

London in Pictures is a guide-book, but a guide-book with a difference as the foreward to the book describes:

“Many London guide books are published every year and many picture books illustrating the external beauties of London streets and street scenes and buildings of architectural and historic interest. None of these publications, however, devotes adequate attention, even if any notice at all be given, to the municipal interests of London”

The guide-book was targeted at visitors to, and those on holiday in London, and the foreward goes on to explain that if the visitor can understand the government of the city and how London is delivering municipal activities, they can take back this knowledge to help solve problems in their own town or city. Possibly a very limited readership, but again, this demonstrates the LCC’s pride in the way that London was administered and the services provided to the city’s inhabitants.

The book is divided into sections focusing on a specific aspect of the LCCs services, so lets start with – Block Dwellings built by the Council.

In 1937 the LCC owned around 25,000 flats across London. These were typically in estates with blocks of flats to a common design, however many designs were unique and still look good today.

One of these was the Oaklands Estate in Clapham. This estate occupied around 3 acres and provided 185 dwellings with a total of 582 rooms. The estate was built between 1935 and 1936 and the following photo is of Eastman House on the Oaklands Estate.

The Clapham Park Estate is of the more traditional London County Council design. This is a view of Lycett and Cotton Houses on the estate which was built between 1930 and 1936, with the overall estate comprising 759 dwellings.

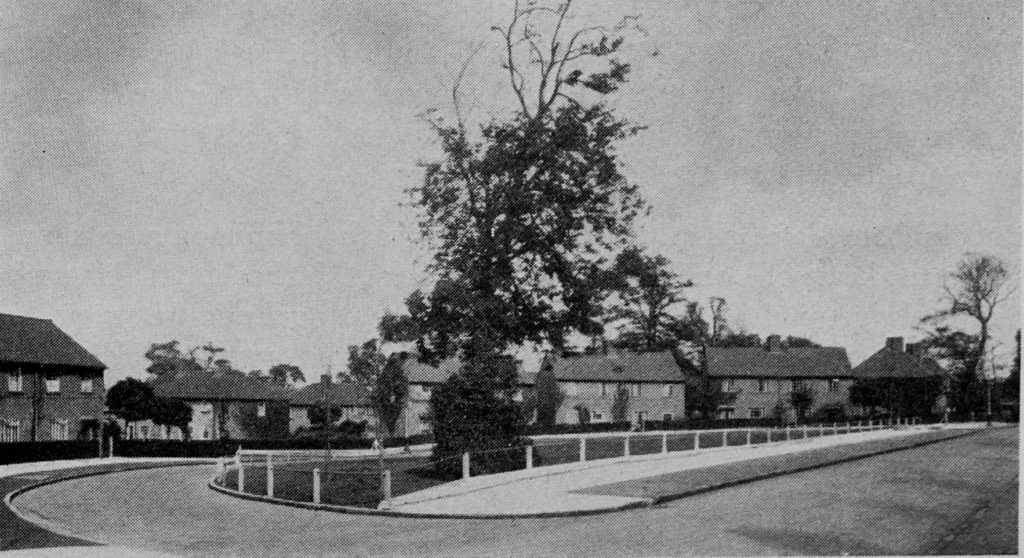

The LCC also developed Council Cottage Estates. These estates consisted of houses and smaller flats, providing a low-rise appearance and reduced housing density. This is the Old Oak Estate – the estate which is located between Westway (the A40 road) and Wormwood Scrubs.

In 1937 the Old Oak Estate consisted of 1,055 houses and flats.

Occupying around 202 acres of land across Chislehurst and Sidcup districts was the Mottingham Estate. In 1937 the estate consisted of 2,356 houses and flats with further growth planned by the reservation of space for a cinema, shops, schools and a church and 25.5 acres of open space.

Londoners also needed education and the London County Council designed new school buildings with large windows for natural lighting, assembly halls, gymnasium, libraries and rooms designed for specific subjects such as science and art. The book highlights that LCC schools were provided with hot water facilities (with the implication that earlier schools lacked this feature).

This is the King’s Park School in Eltham. The senior school in the two storey block with the single storey infant school to the right.

As well as education, health care was important, and in 1937 the NHS was still a distant dream. In 1930 the LCC took over responsibility for hospitals controlled by Boards of Guardians and the Metropolitan Asylums Board. This allowed the council to start a programme of modernisation and standardisation of health services across the city and in 1937 there were 43 general hospitals and 31 special hospitals controlled by the LCC.

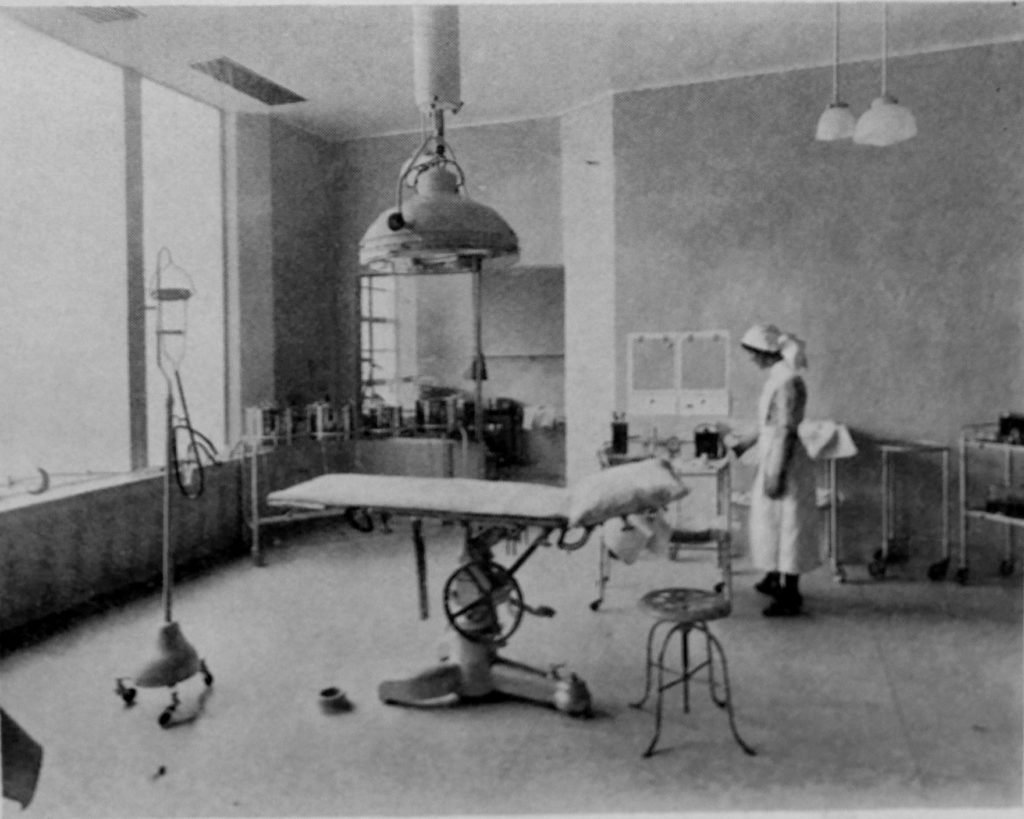

This is the Operating Theatre and X-Ray Unit completed in 1936 at St. Mary Abbots Hospital, Kensington.

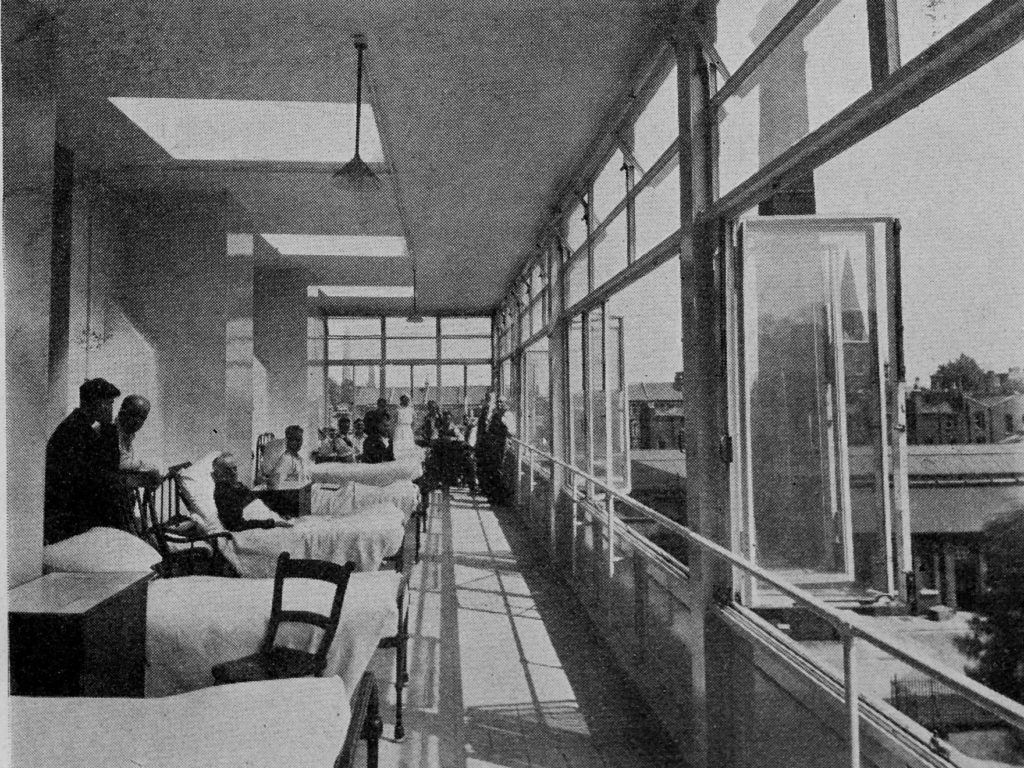

As with new schools, LCC designed hospitals also featured large windows to maximise natural lighting and a belief in the importance of fresh air to aid recovery. This is the Sun Balcony at St. Olave’s Hospital:

As with new schools, LCC designed hospitals also featured large windows to maximise natural lighting and a belief in the importance of fresh air to aid recovery. This is the Sun Balcony at St. Olave’s Hospital:

One of the departments within the London County Council was the rather 1984 Orwellian named “Public Control Department”.

This department had a wide range of services which today would be included within the scope of departments such as Trading Standards.

The Public Control Department was responsible for services such as for weights and measures, testing of gas meters, control and storage of petrol, licensing employment agencies and massage establishments, administration of the Shops Act, diseases of animals, sale of fertilizers and animal feed stuffs and the registration of theatrical employees.

The following three photos from the book show the type of activities carried out by the Public Control Department. The first is testing a weighbridge:

Measuring the weight of a sack of coal to ensure that the contents met the specified and charged for weight:

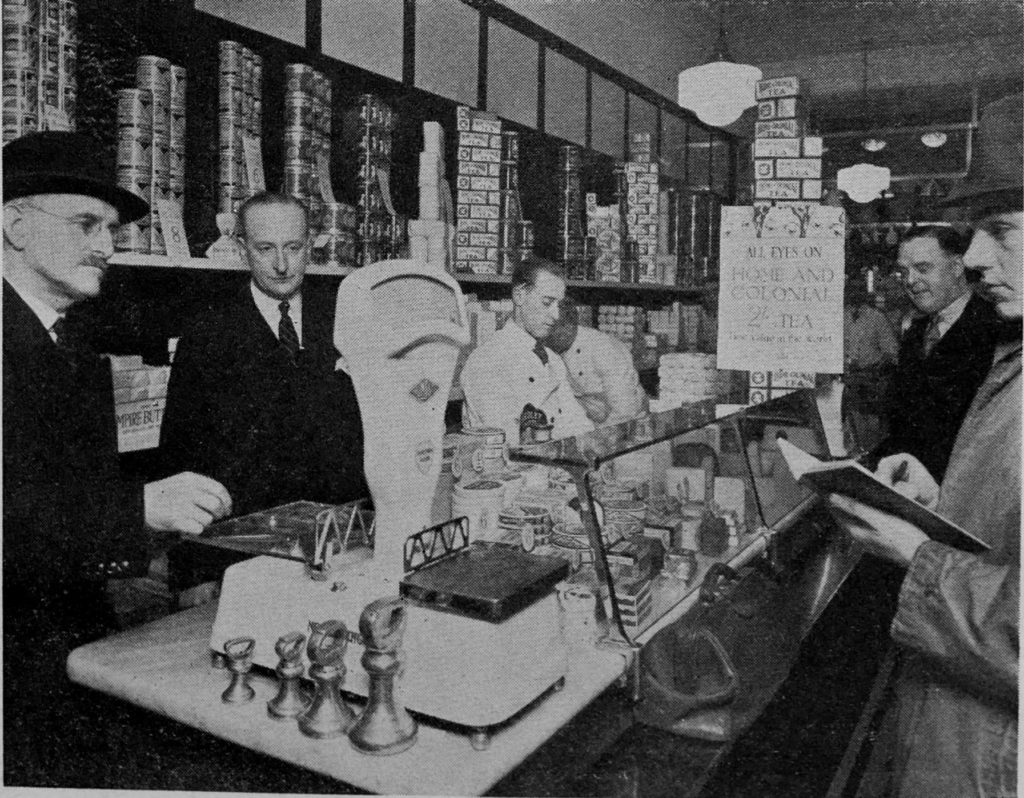

Checking the weights and measures in a shop:

The London County Council became the local education authority for London in 1904, and was responsible for:

- To co-ordinate the activities of its predecessors, the School Board for London and the Technical Education Board,

- To place those elementary schools provided by voluntary bodies on the same basis as regards maintenance as those provided by the Council itself,

- To establish a system of secondary schools linked to the elementary schools by a scholarship scheme,

- To reorganise the former ‘night schools’ into a comprehensive system of continuative education,

- To expand technical, commercial and art education,

- To build up a system of school medical inspection and treatment, and of special schools for children with physical and mental defects.

In 1937 the LCC was responsible for nearly 800,000 pupils. 512,000 under the age of 14, with 125,000 between 14 and 18 and a further 163,000 in adult education.

An annual nativity play by junior boys and girls:

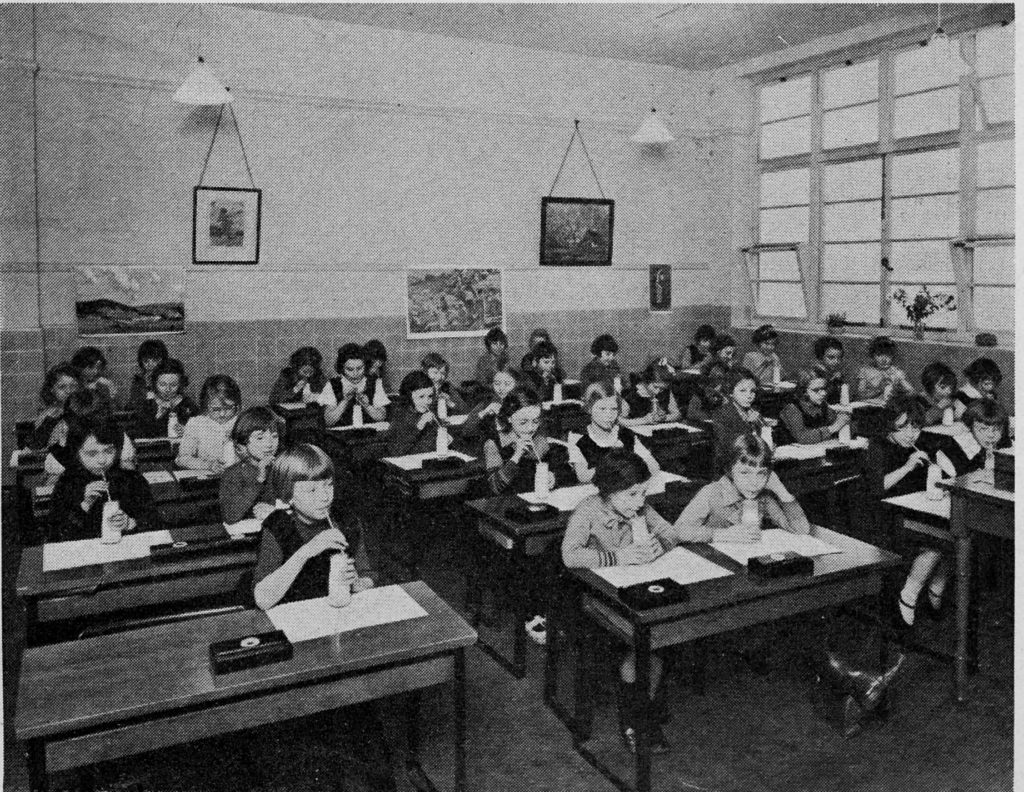

Mid-morning milk at a junior school:

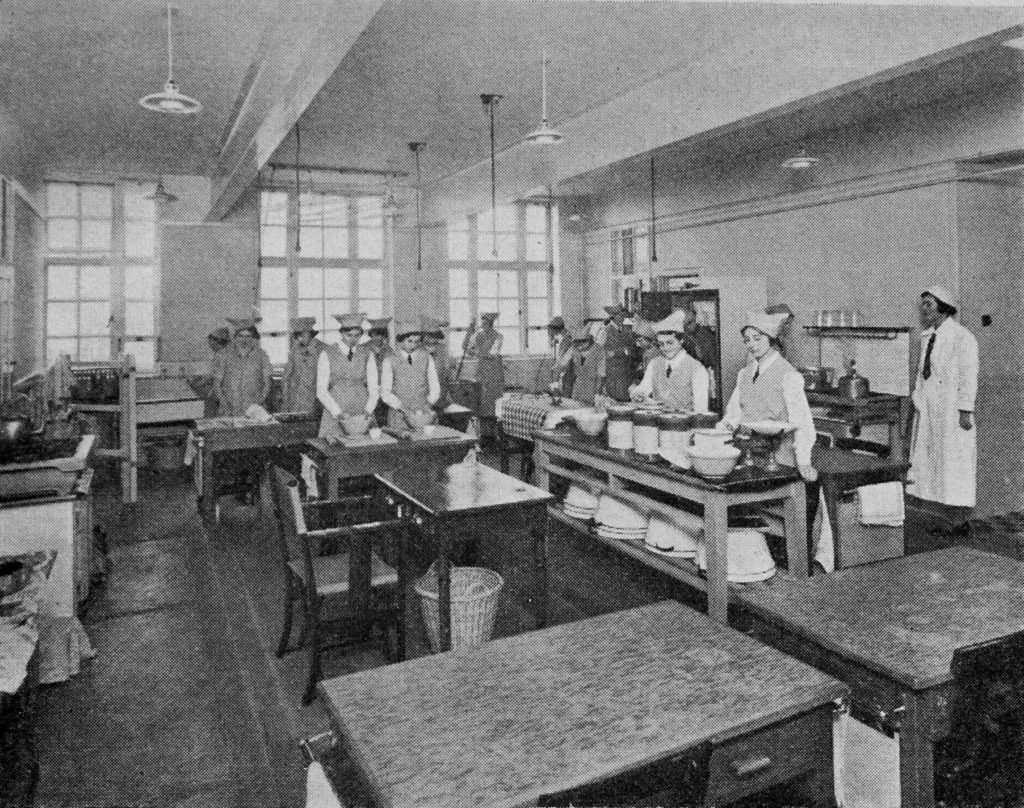

Practical work – Domestic Subjects:

Residential schools in camp:

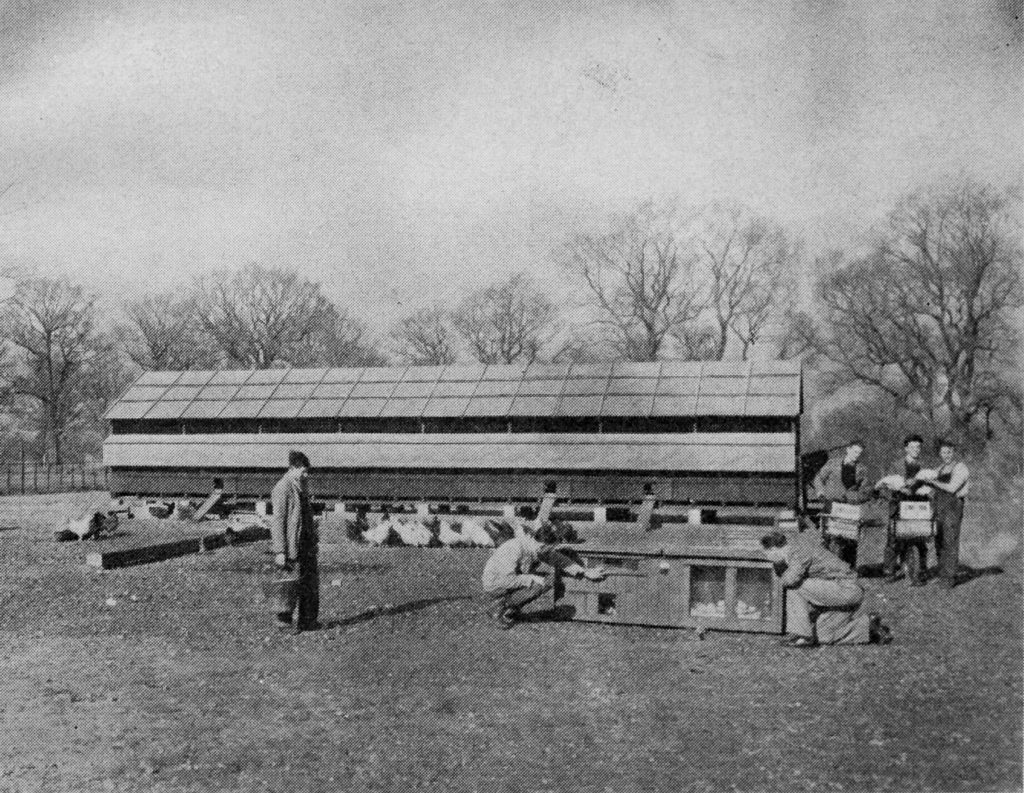

The scope of education covered by the London County Council included training colleges which focused on specific subjects and skill sets. These colleges included teacher training colleges and in the photo below, poultry farming:

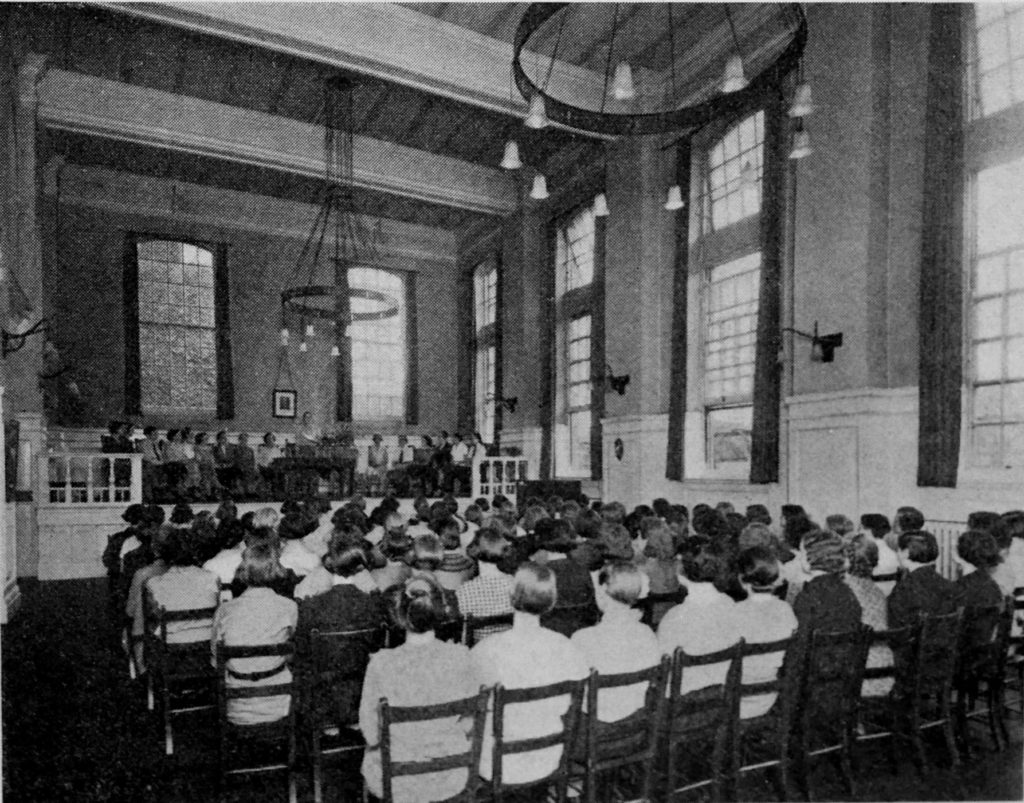

A teacher training college:

The London County Council was also responsible of the main drainage services for London, which in 1937 meant servicing the needs of 5.5 million people.

The main treatment works were at Beckton, which dealt with 280 million gallons of sewage a day, with effluent being discharged into the river, and 2 million tons a year of solid matter being dumped at sea by a fleet of four, wonderfully named “sludge vessels”.

This view is of part of the 7.5 miles of aeration channels at Beckton:

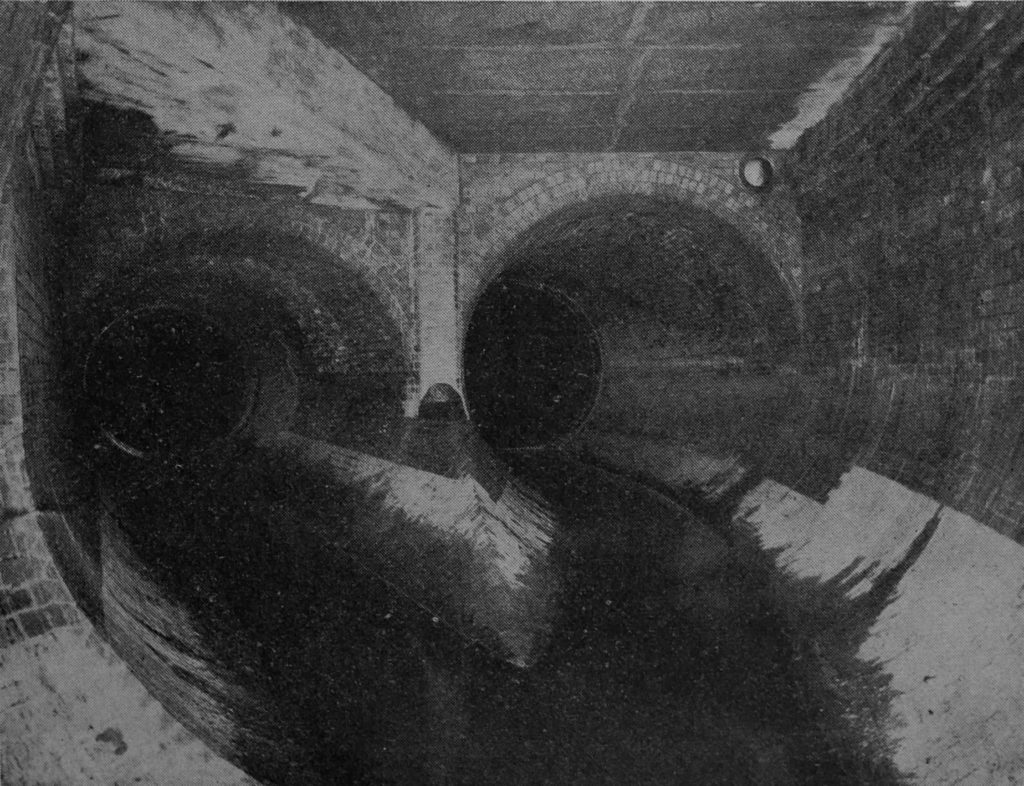

An example of the tunnels that transported sewage for treatment – 10 foot and 11.5 foot diameter sewers:

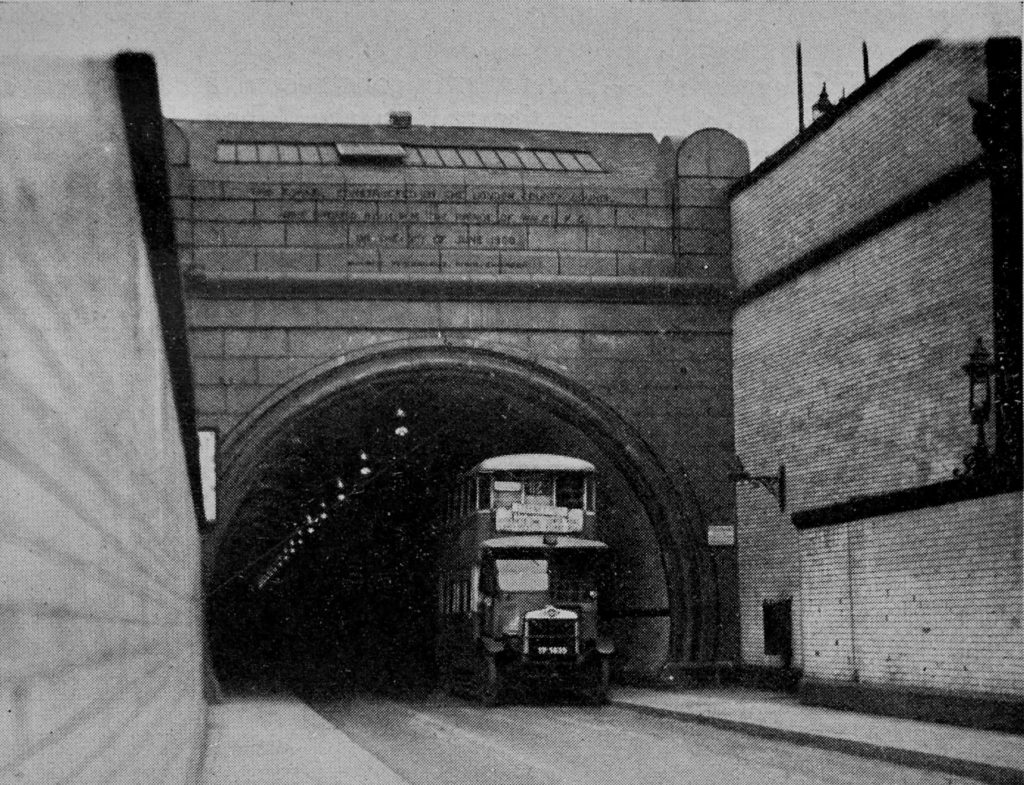

Included within the wide range of infrastructure services for which the LCC was responsible were ferries, tunnels and piers, including the Rotherhithe Tunnel:

Greenwich Pier:

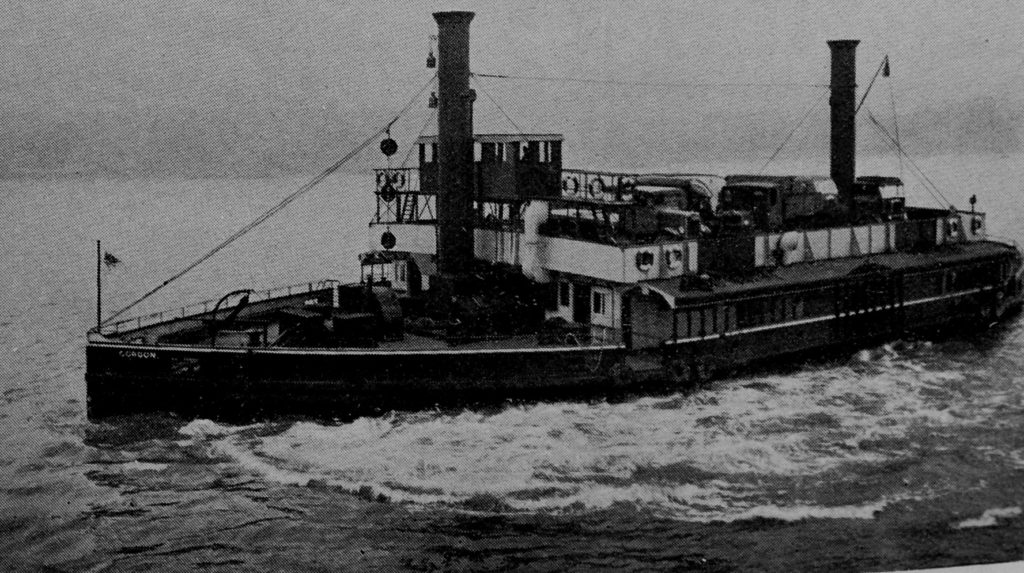

And the Woolwich Ferry, which in 1937 carried 4,000 vehicles and 7,000 pedestrians daily between the weekday hours of 6 a.m. and midnight.

Originally, fire brigade services had been built up across London by private enterprises such as insurance companies, however by the 1860s, the costs of providing the service were escalating and the insurance companies requested that the Government took over the service.

This was achieved by the 1865 Metropolitan Fire Brigade Act which consolidated the individual services into a single, London fire service.

In 1889 the London County Council took over the Metropolitan Fire Brigade, and in 1904 the name was changed to the London Fire Brigade.

In 1937 the new headquarters building and fire station for the London Fire Brigade on the Albert Embankment had only just been completed. The fire services moved from this building a few years ago, and it is currently being redeveloped, however it will retain a link with the fire service as the London Fire Brigade museum is planned to return to a new and upgraded facility within the building.

In 1937, the London Fire Brigade were equipped with a range of leading edge appliances, including a Hose Lorry:

And a Breakdown Lorry:

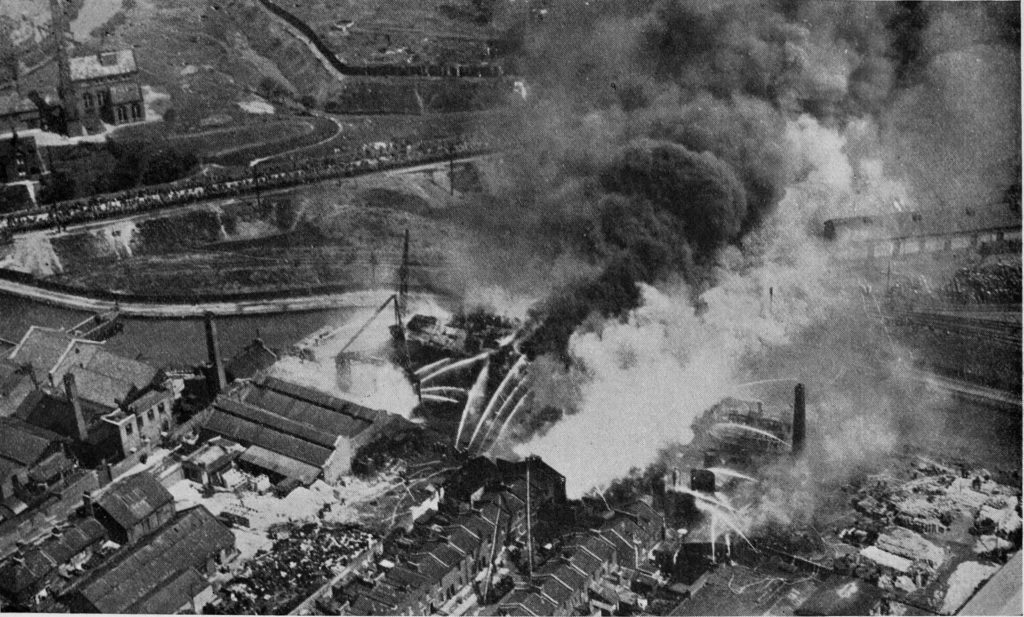

The London Docks were a high fire risk, due to the dense storage of large amounts of inflammable materials, with probably a lack of attention to fire prevention measures. The following photo from the book shows a typical fire that the London Fire Brigade had to deal with, a large fire in July 1935 at Iceland Wharf, Old Ford.

The Municipal Hospitals of London were the responsibility of the London County Council, with 74 hospitals taken over from the Boards of Guardians and Metropolitan Asylums Board.

In 1937, these hospitals contained at total of 38,500 beds. This was before the establishment of the NHS, so treatment was not free for all. The book explains that “Admission may usually be secured on the certificate of a private doctor, without any suggestion of poor law ‘taint’, and except in certain circumstances, patients are required to contribute according to their means.”

The Children’s Ward at a LCC hospital:

A London County Council hospital operating theatre:

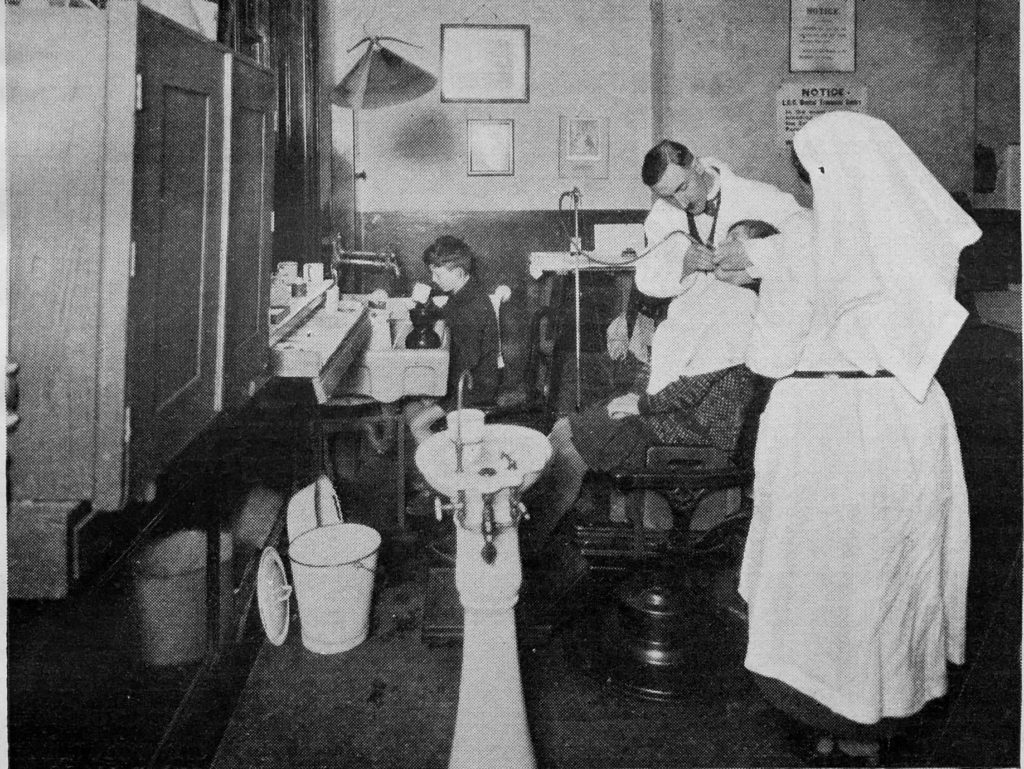

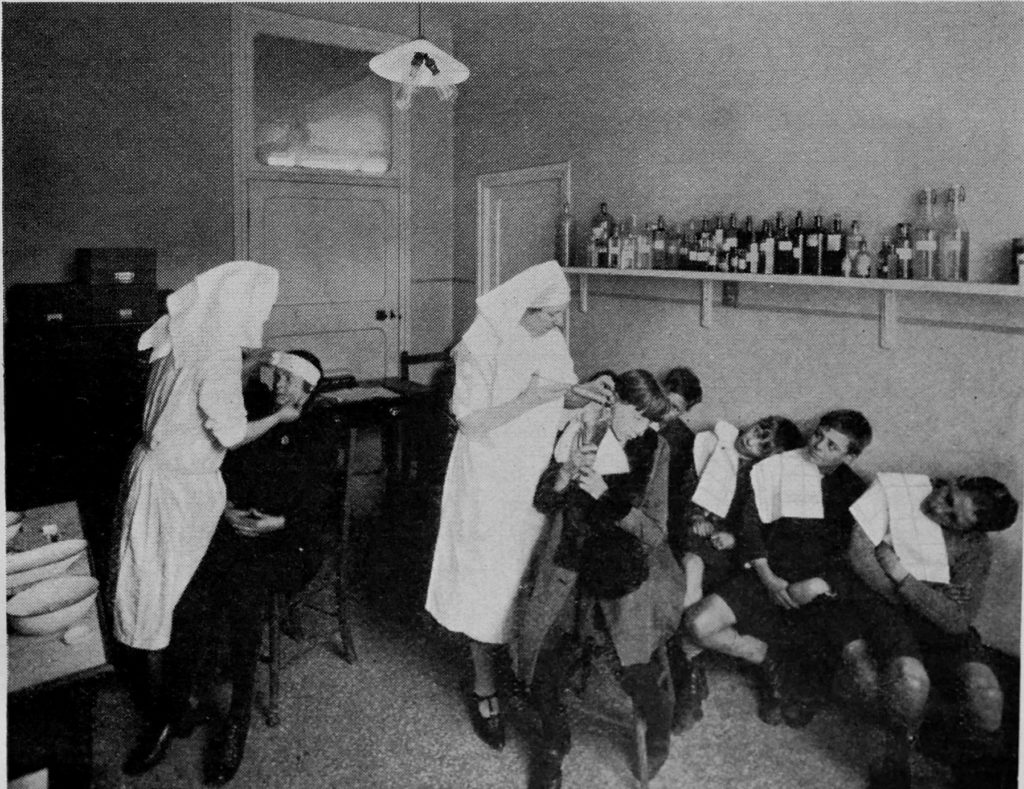

The London County Council also ran medical inspections and treatment of school children. Children would be ‘inspected’ at the ages of 7, 11 and between the ages of 13 and 14. This included dental inspections with the possibility of follow-up treatment at 74 medical and dental treatment centres across London.

Probably a nightmare for most children – school dental treatment:

A minor ailment centre:

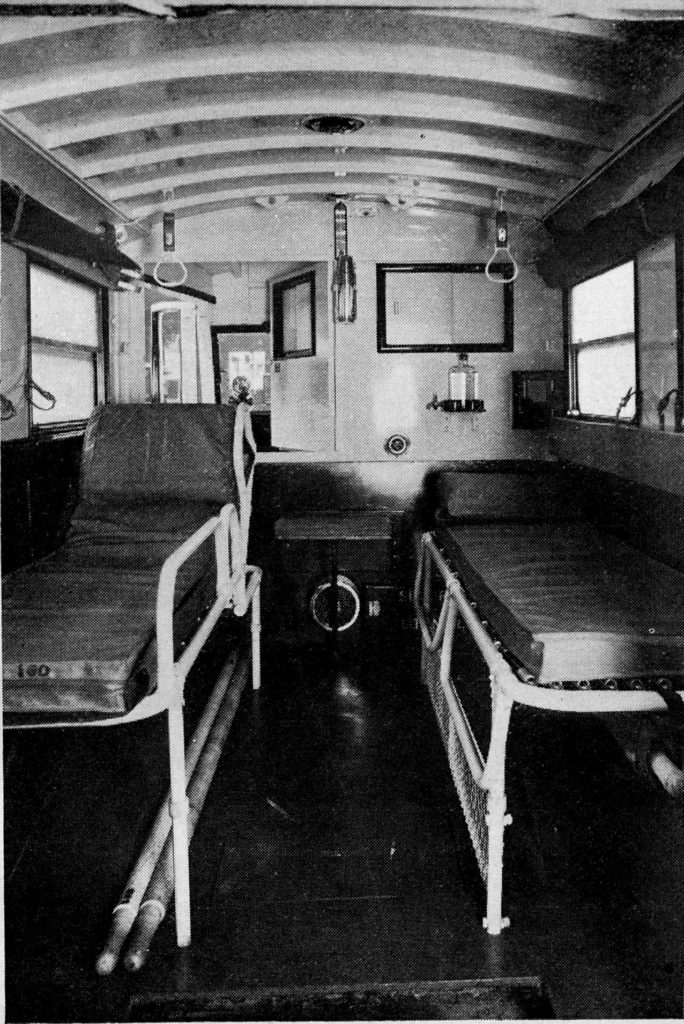

The London County Council set-up the London Ambulance Service in 1915, initially to focus on street accidents. There was a separate ambulance service run by the Metropolitan Asylums Board, which was used for the transfer of patients with infectious diseases, and another service run by the Boards of Guardians. All these services came under the central control of the LLC in 1930 under the Local Government Act of 1929.

The interior of a 1930s ambulance:

Control of ambulances was from County Hall and an ambulance could be summoned by calling WATerloo 3311.

in 1937 there were 153 ambulances covering London. These were based at 6 large ambulance stations and 16 smaller stations. By comparison in the financial year 2017/18 the London Ambulance Service consisted of over 1,100 vehicles based at 70 ambulance stations and support offices across London. In the same year the service dealt with 1.9 million 999 calls – a truly extraordinary number.

If you needed an ambulance in 1937, this is the vehicle that would arrive:

Parks and Open Space were also the responsibility of the London County Council, with a total of 6,647 acres of space managed by a staff of 1,500.

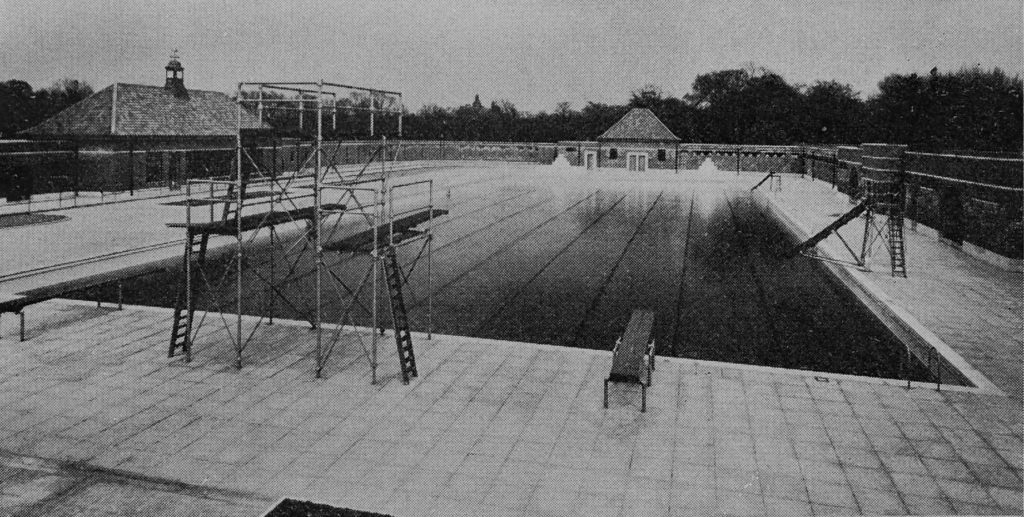

The LCC provided and managed parks such as Battersea Park, as well building and managing facilities within parks, such as the open-air swimming pool at Victoria Park:

One of the responsibilities of the LCC, in the terms used in the 1937 book was the “Care of the Mentally Afflicted”. The LCC had started to change how mental health was treated with a move from the custodial approach to proper nursing care, however it was a very institutionalised approach with 20 hospitals and institutions providing treatment for 33,600 patients from a staff of 9,000.

This is Forest House, the admission and convalescent villa in Claybury Hospital:

In the same hospital, the Needleroom where “many patients can still do useful work”.

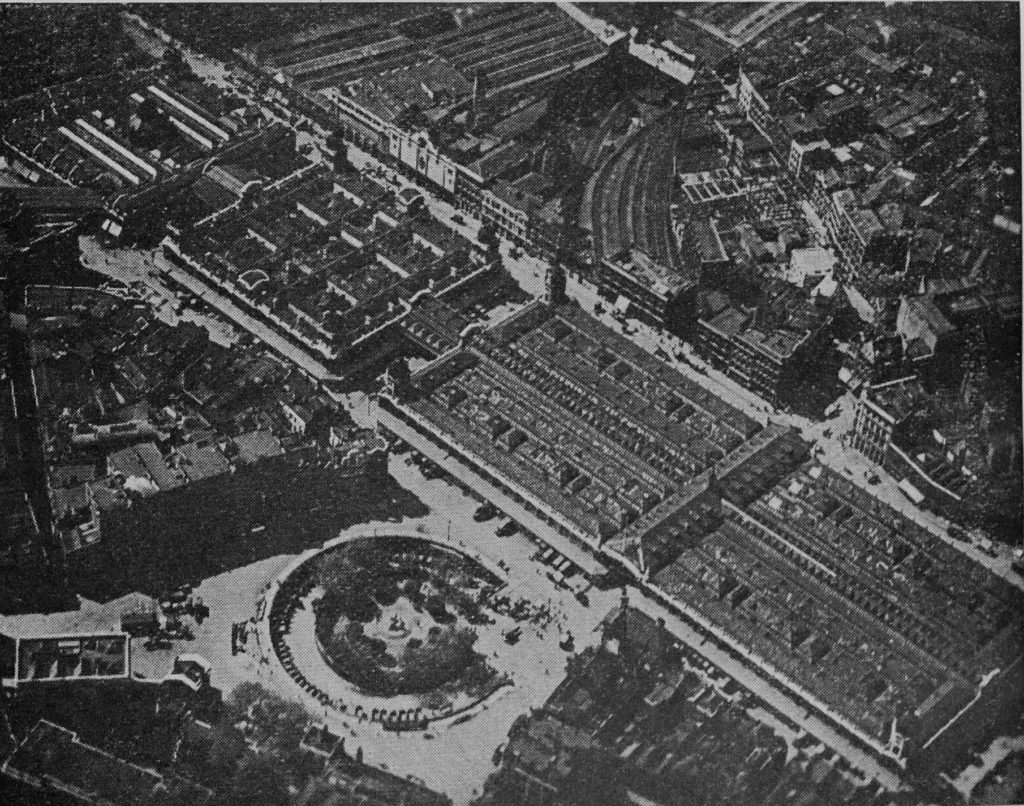

The guide-book also included the other governance authorities within London, including the City of London Corporation. This included the City markets, with this superb aerial view of the London Central Markets at Smithfield:

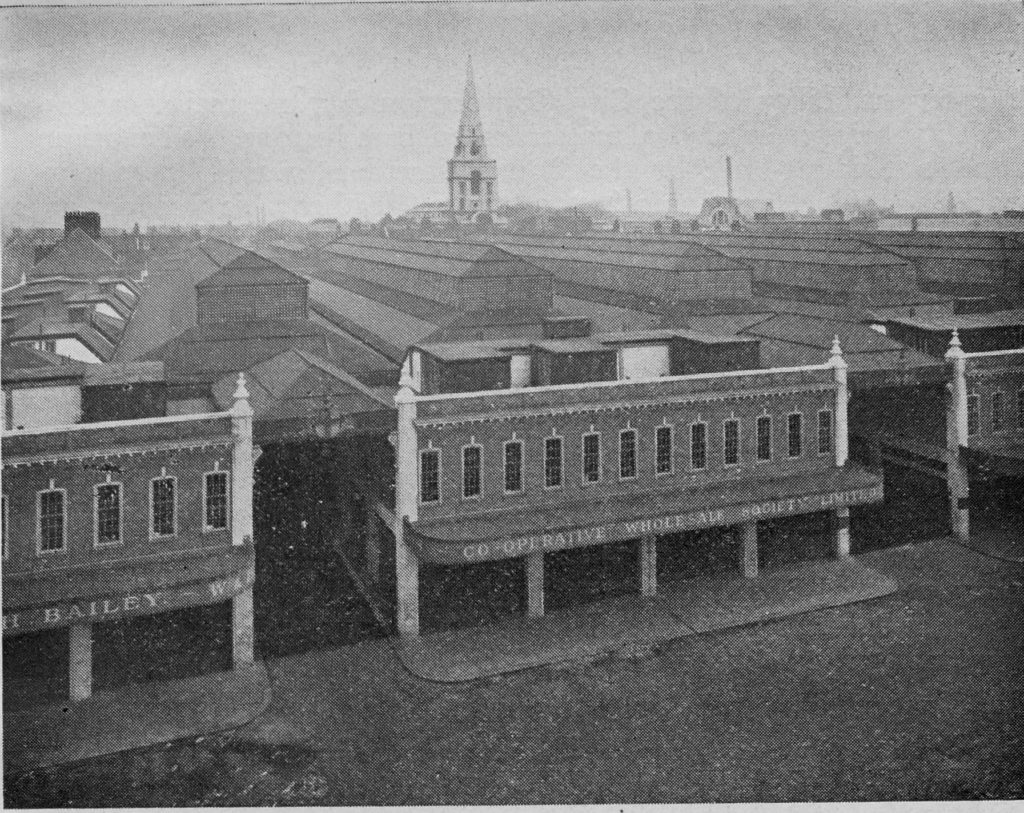

And a very quiet Spitalfields Market:

The other key element of London governance were the Metropolitan Borough Councils. These were formed by the 1899 London Government Act and were responsible for a number of local services such as the collection of refuse and the maintenance of streets.

In 1937, 16 out of a total of 28 borough councils were still electricity supply authorities, having their own local generation and distribution capabilities. These services would not consolidate further until after the war with the creation of the Central Electricity Generation Board and the regional distribution boards, such as the London Electricity Board.

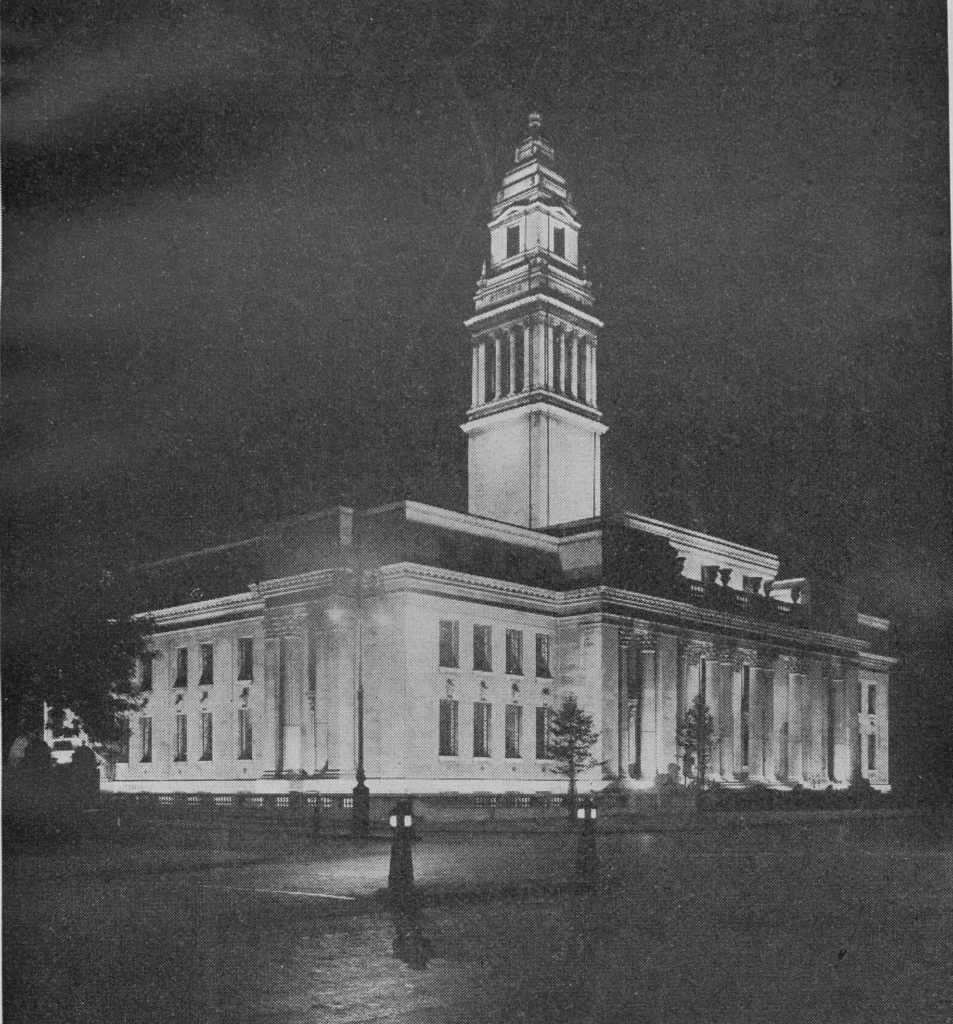

The establishment of the Metropolitan Borough Councils resulted in the building of impressive Town Halls across London. The book includes a night view of St. Marylebone Town Hall:

Municipal Borough Councils also provided local facilities, for example, local parks and playgrounds, libraries and swimming pools.

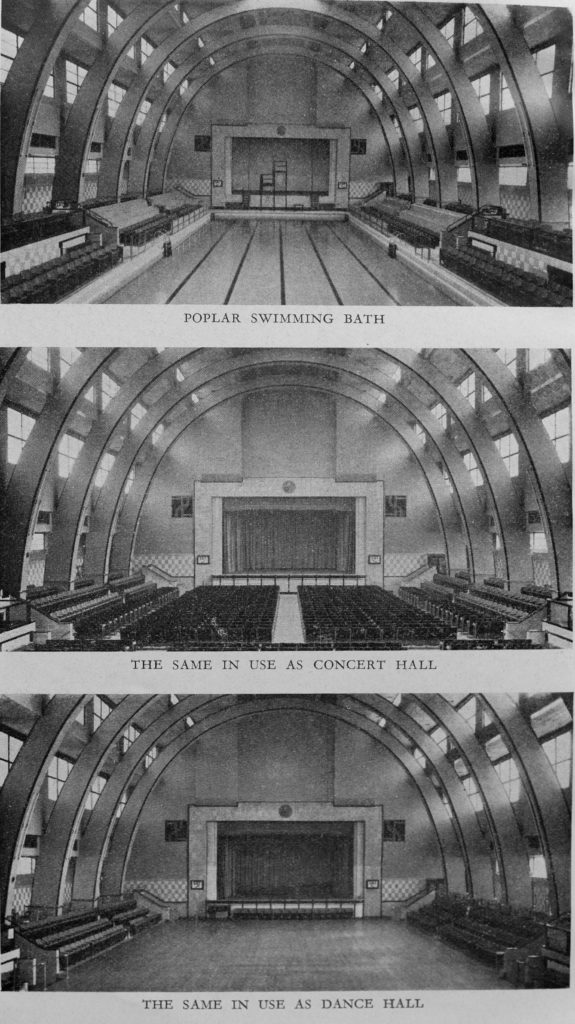

One impressive example in 1937 was the Poplar Swimming Bath and the books show how the same building could support very different uses:

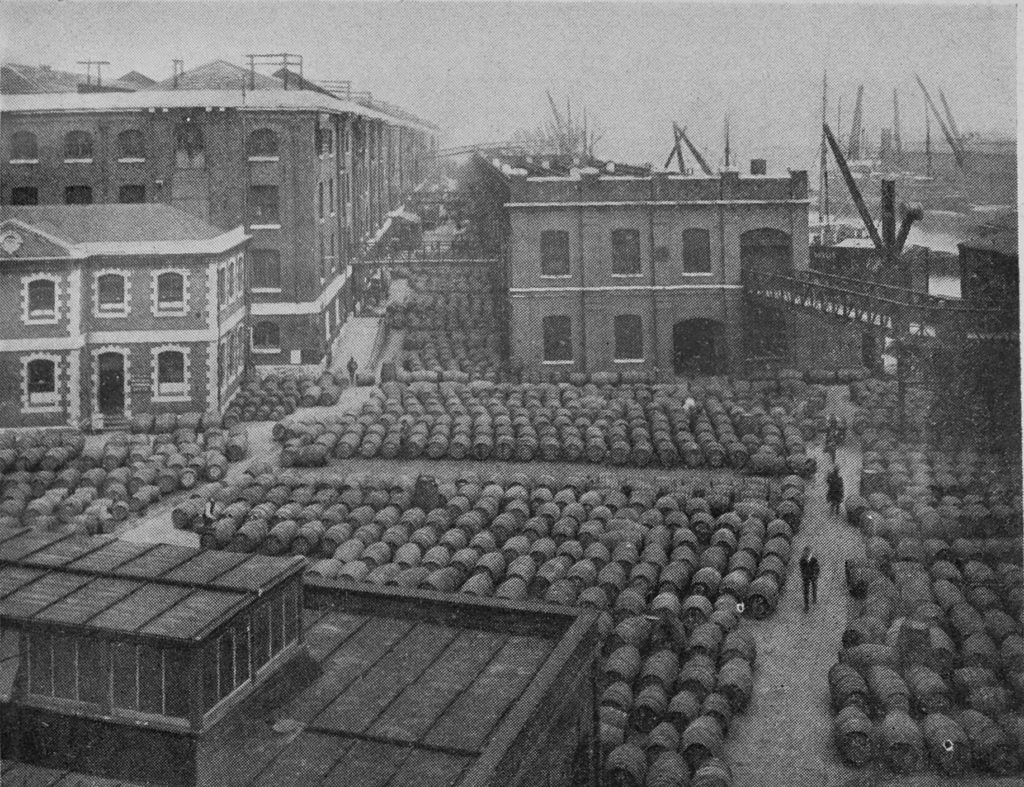

In 1937. the London docks were still major centres of trade. Containerisation and the shift of ports from inland rivers to coastal centres such as Southampton and Felixtowe was still decades in the future.

The Port of London Authority was responsible for the management of the ports and river. In 1937 the Port of London dealt with more shipping than any other UK port and over a third of UK overseas trade passed through London. In 1937, approximately 43 million tons of goods were managed through the London docks.

A ship entering the King George V Dock:

The Wine Gauging Grounds operated by the Port of London Authority:

London County Council publications are always fascinating and London in Pictures provides a really good overview of the governance of London and the breadth and depth of the services provided by the LCC.

Two years after the guide was published, the Second World War would bring devastation to the city, but would also mark one of those break points in history with, for example, the coming NHS taking over the provision and considerable expansion of health services.

The London Docks would soon start their gradual decline which would end in the closure of all central London docks. The population of London would also reverse the centuries long expansion and would go into a decline that would only start to recover in the 1980s.

Council house provision would reduce to almost nothing and “right to buy” would transfer council owned accommodation into private ownership.

The 1937 guide therefore provides a snapshot of LCC services at the end of an era.

Really excellent description of the LCC. It was the model for the 1945-1941 creation of the Welfare State across the country in many ways.

My mother was employed by the LCC to give ‘home tuition’ for children who could not go to school during the late 1950’s and early 60’s. She would visit for a few hours each week so it was quite basic!.

Thank you so much. This is (as always) a fascinating post. So much so that I have managed to buy a copy of the publication and am planning to visit the archives in Clerkenwell ASAP.

Fascinating post as always thank you. My uncle George Hilleard was a photographer for the LCC and I’m always interested in the photographic work that was done as I have little information myself, but like you with your father, l’ve been visiting my uncles past locations, though. on his days out of London!

An interesting post,Admin,where do you find these old information leaflets?

I particularly liked the photograph showing the 82? bus emerging from the Rotherhithe Tunnel. I’ve told my husband that double decker buses used to run through there,even to the fifties/early sixties? I don’t think he believed that they could get through. The bus terminated at the Limehouse end and its stand was outside the block of flats there.

Did have a chuckle at the clinic picture,all those little boys waiting to have their ears syringed!!

Great episode look forward to the next

From C19 the LCC set so many standards, how many are left post Thatcher, etc?

Absolutely fascinating post on the LCC.

My Uncle Dennis worked on a swing bridge in the Docks. According to him, the Beckton ‘sludge vessels’ were also known by PLA staff as the Bovril Boats 😉

It is a wonderful book as are the slender volumes the LCC produced on its various services such as housing, the ambulance service and the Fire Brigade. As people say it was a remarkable organisation and one can only reflect on the civilising nature of much of its work.

Fantastic information providing a real social structure sadly lacking today ,

Look forward to next Sundays post.

This is superb – thanks very much for scanning the LCC book. I know the Council went a bit over the top sometimes, but it’s such a contrast with the current somewhat bleak situation. Well done Herbert Morrison, now there was a man with vision.

The dreams we had then for a wonderful future. Thanks for these great pics.

BTW every road on the Old Oak estate is named after a Pre-Reformation Bishop of London.

The impression is of an administration with confidence, wishing to do the correct thing and spending the money that was needed to deliver the vision. There was a sense of investing in the community.

Now there is a lack of vision and a desire to spend less so that taxes can be cut for those who don’t need it. The Government views all outlays as expenditure rather than investment with dire consequences in housing provision in particular. But I visit London regularly and can assure you that things are not so bad as they are in Brexitland (the North) where I live. Here the councils have been crushed under the weight of savage cuts and there is huge resentment.

I taught in a school that was built in the 1950s and looked very similar to Kings Park, Eltham that you show here. It was demolished because it occupied land that was valuable for housing! Stupid vandalism but I can’t blame the council. They have some invidious choices to make.

Thank you for showing what visions a previous generation had and how they tried to deliver it. Can we ever return to that?

So interesting. I taught in several 1930`s built school in london in the 1970`s. They were lovely light airy buildings compared to the Victorian built schools I also taught in !!

Great blog. The pictures of the fire appliances were taken in the Old Southwark Training Centre, Southwark Bridge Road. I worked for the LFB when they were still using the Training Centre and was based at HQ at Albert Embankment. I was lucky enough to be able to get involved in some of the open days and also had access to the archive, which I used for some work on the history of the brigade (amateur work).

Another very interesting post, the photos are great and really take you back to a bygone era

As always, a fascinating and informative post. Very interesting to read of the increase in so many services since 1937. Though I see that in some other areas the LCC services have declined, or at least moderated, since its earliest years. New London: Her Parliament and its Work, published in 1895 by the Daily Chronicle, states that London’s municipal parks were claimed to be almost self-supporting and the Council employed breeders for their aviaries who ‘sell better known varieties and buy more valuable ones’. And though several London parks have bandstands now, I’m not sure if the LCC still has ‘a uniformed County Council Band of 100 members, divided into four sections’.

A fascinating story though it is, I am not sure why you included the Port of London Authority as this has been a self-funding public trust since it was established in March 1909 and had no connection with the LCC.

One thing that the LCC did do (but not included here) was to operate trams. Under the Tramways Act 1870, local authorities were permitted to acquire privately-operated tramways in their area after they had been operating for 21 years. Accordingly, in October 1891 the LCC exercised its option to take over 4.5 miles of route operated by the London Street Tramways Company. By 1933, when the trams were absorbed by the London Passenger Transport Board, the LCC had 167 miles (269 km) of tramway in operation.

Over a year on and I am just starting to catch up with varied blog posts that need time to read and absorb. This one, as with all your posts, deserved a careful read – writing them all must take even longer and as ever I’m enormously appreciative of all your research and careful writing-up. I greatly mourn the loss of the concept ‘for the public good’ and this post provides excellent illustrations of what we still think of as good compared with those we’re no longer so happy about. More reflections please, when you have time(!) on what you find when you dig deeper into such concepts and what prompts you to say ‘comparisons are never simple’.