For this week’s post, I am in Charing Cross Road to track down a couple of photos I took in 1979, and a later “shop front” photo from 1986.

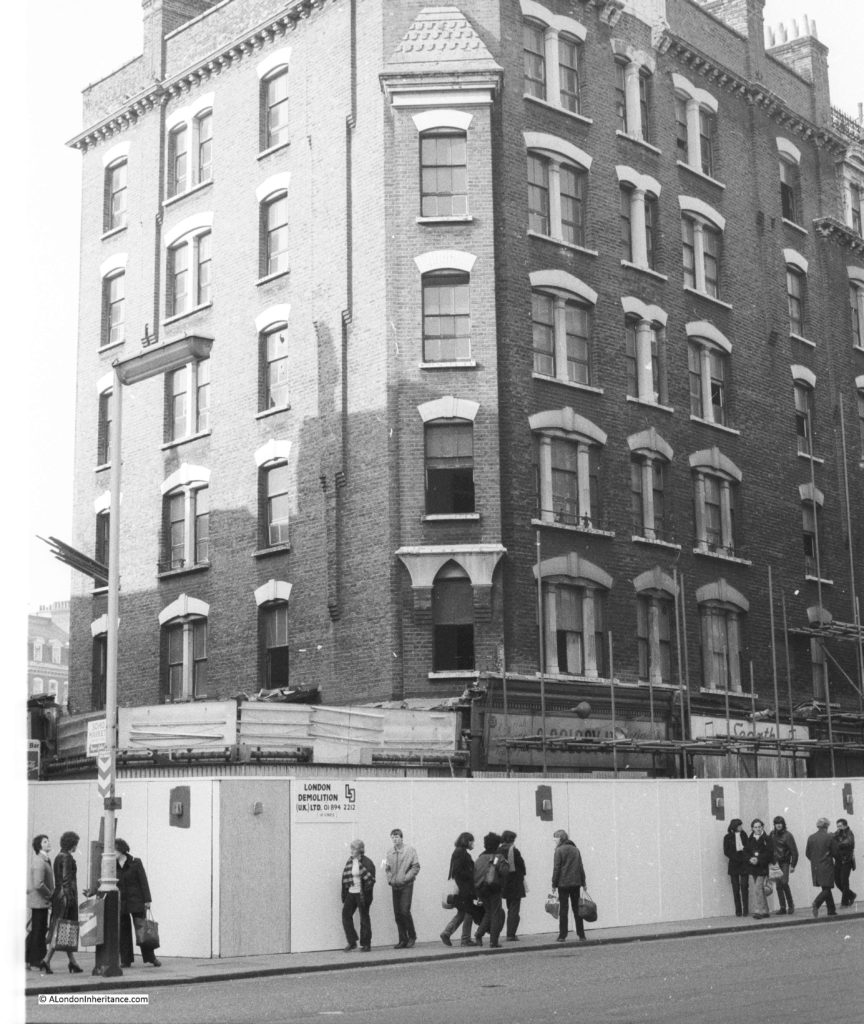

This was the view in 1979, looking north along Charing Cross Road, close to the junction with Great Newport Street.

The same view in 2019:

In 1979, there were two, almost identical buildings on either side of the street. Both of these were named Sandringham Buildings and were constructed when this length of Charing Cross Road was created. The building on the left in 1979 was replaced by the block we see today, running roughly the same length of the street and with a similar approach of shops on the ground floor and flats on the upper floors.

I took these photos specifically because of the impending demolition of the building – something I have always try to do when I see a building at risk. The following photo shows the corner of the block. The signs of the shops that once occupied the ground floor can just be seen behind the scaffolding.

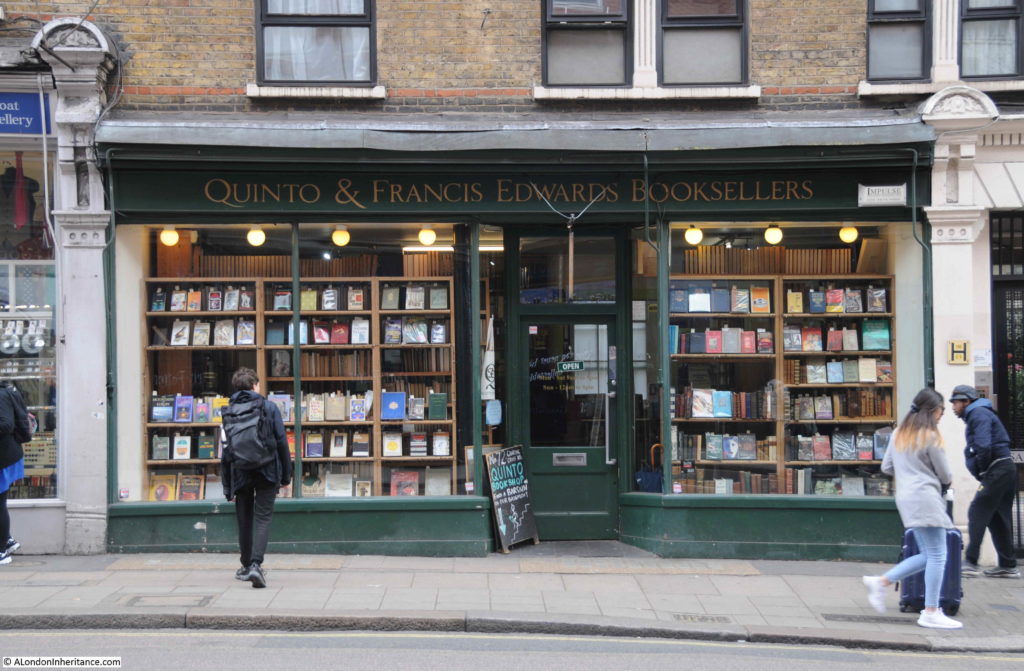

The other location I wanted to track down was this 1986 photo of a tobacconist at number 74 Charing Cross Road, one from a series of shop front photos in the area.

The same location in 2019 – no longer a tobacconist.

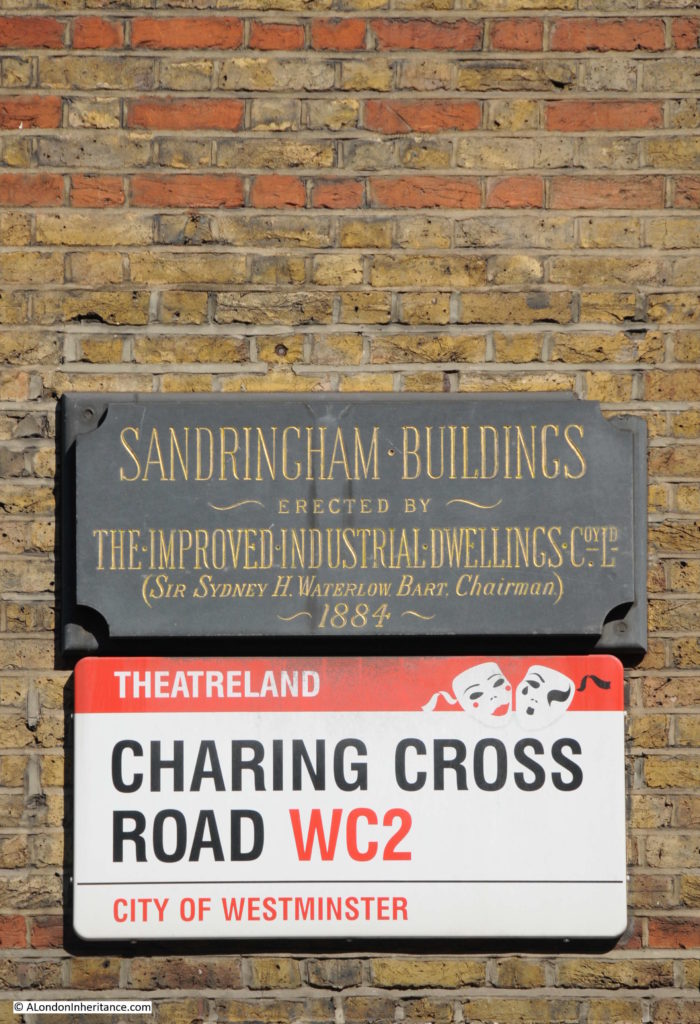

The shop is one of those along the ground floor of the remaining block of Sandringham Buildings, along the eastern side of Charing Cross Road. The history of Sandringham Buildings is integral to the reconstruction of the area that resulted from the development of Charing Cross Road.

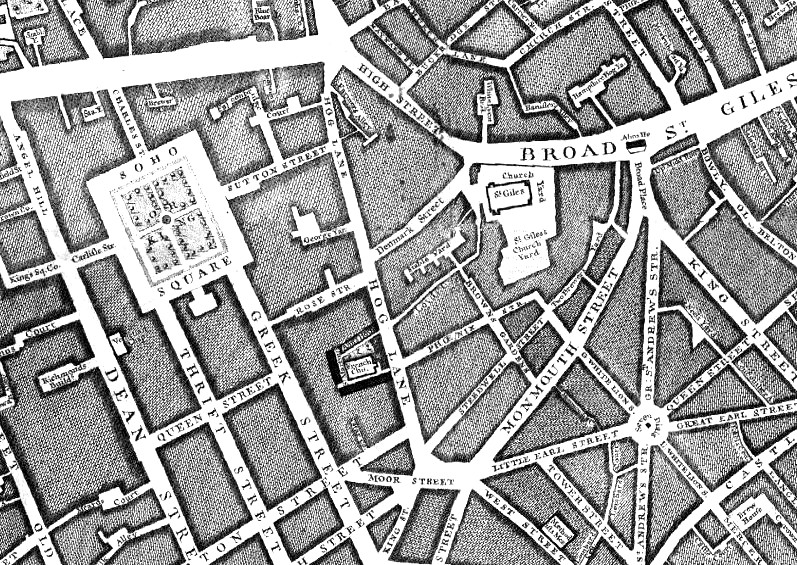

To understand how Charing Cross Road has developed, we can start with John Rocque’s map of London from 1746. Charing Cross Road does not yet exist as a through route from the junction of Oxford Street and Tottenham Court Road, down to the future location of Trafalgar Square. Part of the road that would become Charing Cross Road can be seen in the centre of the map, but named Hog Lane.

The name probably came from the location of a Pound at St. Giles (roughly around the junction today of Oxford Street and Tottenham Court Road), where animals were held as they were driven into London, as a stop before the final push into the City markets (I wrote more about Saint Giles Pound at this link).

Hog Lane ended just north of where Cambridge Circus is today.

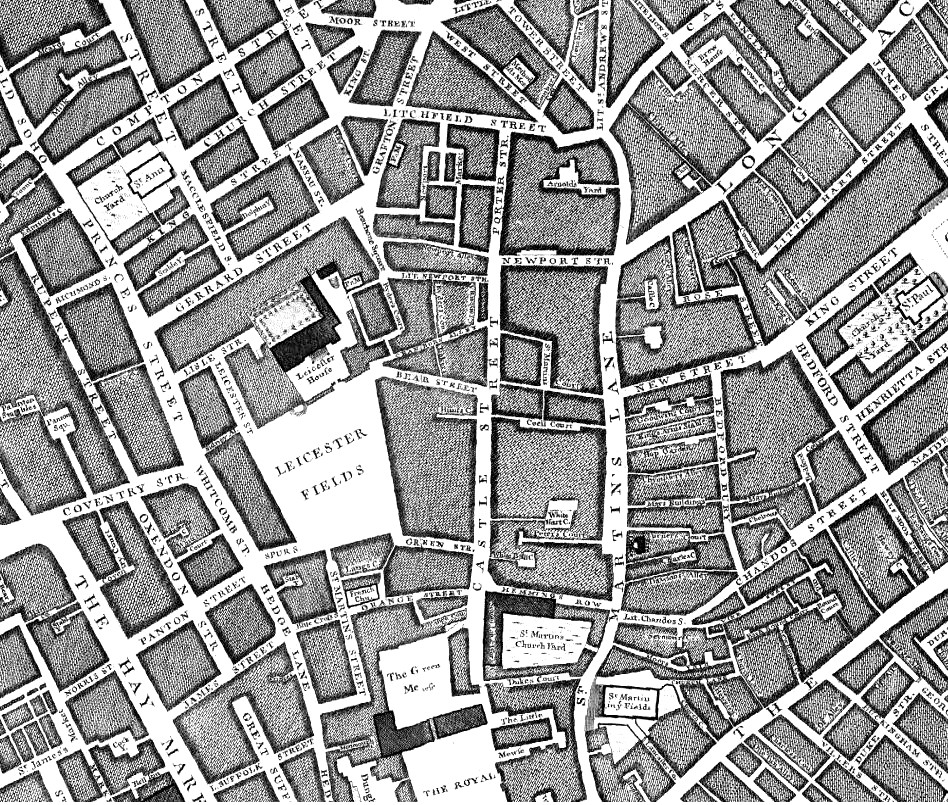

Continuing south, there was no single street running the future route of Charing Cross Road. It was a maze of streets, alleys and courts. In the following extract from Rocque’s map, the future location of Cambridge Circus is in the middle of the top edge of the map, and the future location of Trafalgar Square is at The Royal Stables in the middle of the lower edge of the map.

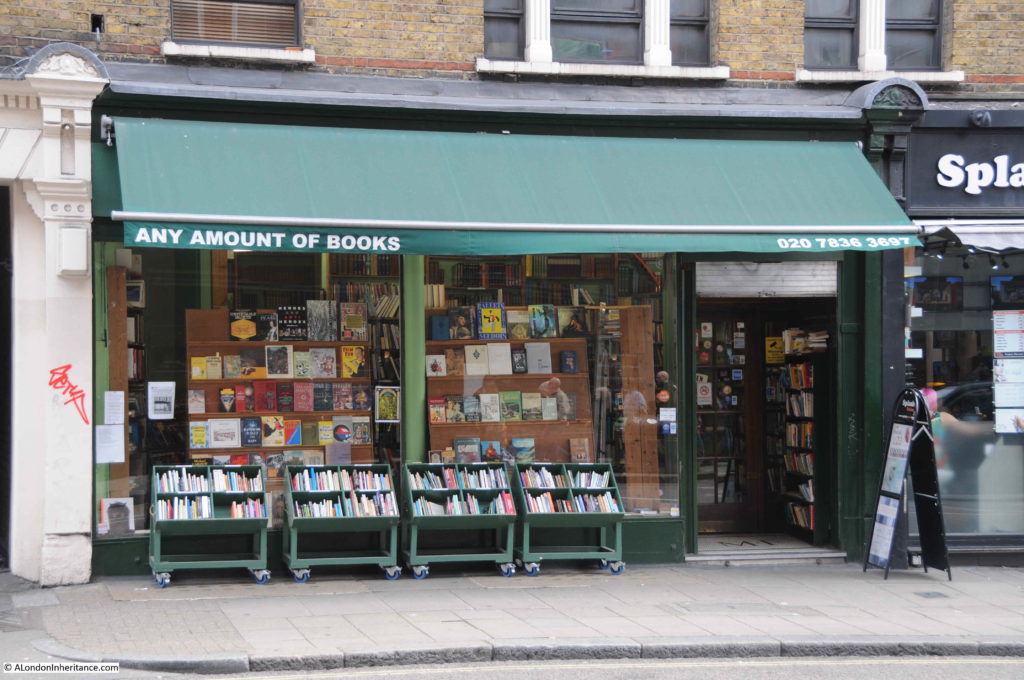

Charing Cross Road has long been known for bookshops. The most famous being Foyles at the northern end of the street, but with many other specialist, new and second hand bookshops lining the street as you walked south.

Many of these have closed over the years, but thankfully a few still remain, holding out against the wave of standardisation across London streets.

Other shops that fill the retail units along the ground floor of Sandringham Buildings.

The development of Charing Cross Road to a single street from Tottenham Court Road towards Trafalgar Square, and the development of Sandringham Buildings can be told through the story of Newport Market.

From the time of Rocque’s map, up to the mid 19th century, the area from what was Hog Lane, around what today is Cambridge Circus, and part of what is now Charing Cross Road to the south was a dense cluster of streets and buildings known as Newport Market.

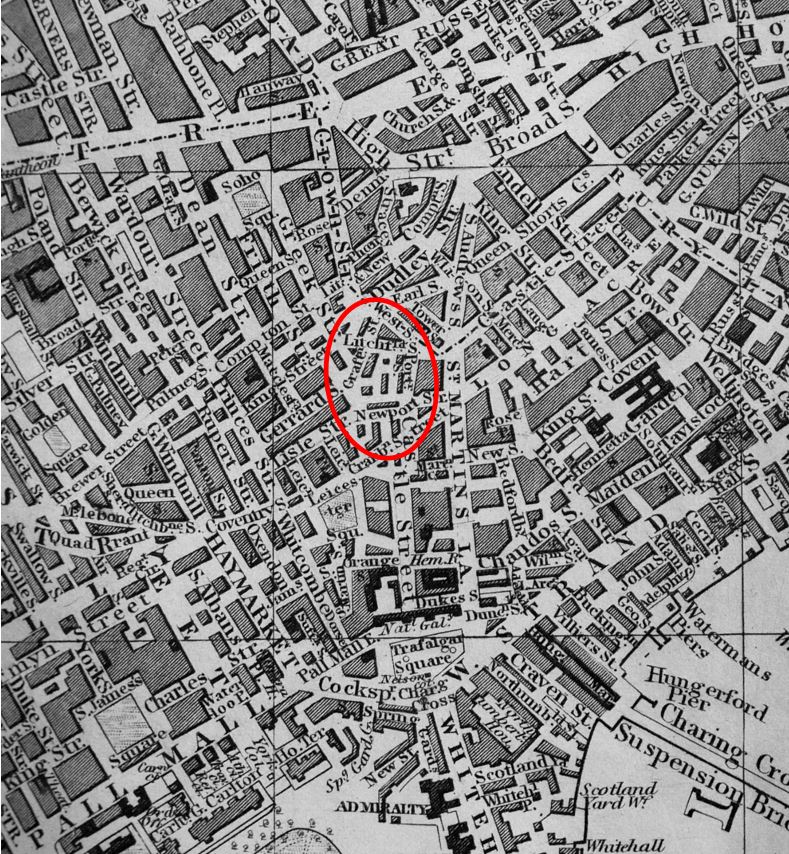

In the following extract from Reynolds’s 1847 “Splendid New Map of London”, I have circled the area of Newport Market with a red oval. To the north is Crown Street, the new name for what was Hog Lane, and the street that will become the northern part of Charing Cross Road.

Trafalgar Square has replaced the Royal Stables, but there is no single, direct street continuing from Crown Street down towards Trafalgar Square.

In 1654, Lord Newport purchased a block of land, which today covers the area from Little Newport Street up to the location of Cambridge Circus. He built a large house and gardens, which would remain until 1682 when the estate was sold and the house demolished. The land was then redeveloped by Dr. Nicholas Barbon who created Newport Market which consisted of a large central square and operated as one of London’s main meat markets.

By the mid 19th century, the area had degenerated considerably and was recorded as providing slum living conditions. An article in the London Evening Standard of the 26th August 1880 titled “Old Newport Market” records how the market had changed:

“Gone are the glories of Newport Market; gone the glory of its Butchers-row. Fashion has this many a year forsaken its uninviting neighbourhood. Beau and buck know no more of its unsavoury haunts. Filth and squalor reign supreme in its courts and passages. Poverty and vice find within its dingy precincts congenial shelter. The old Market, indeed, exists; its walls are still standing. But how changed, how utterly changed, out of all form and semblance. Its shops and sheds are stables and slaughter-houses, its stalls and stands bricked over and built upon. Its very identity is lost; merged, so to speak, in that of prince’s-row, the narrow lane – foul among the foul – that surrounds and gives access to it. Even the name has been taken from it and applied indiscriminately to the adjoining thoroughfare and the unwholesome butchers court that abuts the southern extremity.”

The article then goes on to describe the remaining trades of the market:

“The semblance only, a shadow, as it were, of its former self. A score or so of stalls owned by good-natured Irish women, pipe-loving and rough-tongued. A few eager French women, basket-bearing and garrulous, bargaining for flabby lettuce, unhealthy looking endive and sun-stewed cress. The indescribably nasty row of butchers’; shops in the narrow alley on the right, these constitute the market of to-day, galvanised into fitful activity on Saturday and Saturday night.”

The need for a wide street, linking the junction of Oxford Street and Tottenham Court Road with Charing Cross and the station of the same name that had opened in the 1860s, was part of the 19th century construction across London of direct, wide streets that would address congestion problems and sweep away what were seen to be dense, slum housing.

Plans for Charing Cross Road developed during the 1870s, but there were challenges with land ownership, how much land could be purchased for the new development and the impact on those who lived in the houses that would be demolished. Newport Market was in the middle of the area planned for the extension and widening of the new Charing Cross Road, and the surrounding development.

Finally in 1882, plans were in place, and purchases of property made along the streets that would be demolished. The Illustrated London News on the 19th August 1882 reported:

“Steps have at length been taken for making, at all events, a beginning of a long-needed public improvement, a new thoroughfare between Charing-cross and Oxford-street. The materials of about forty houses about Newport Market have lately been sold by Messrs. Eversfield and Horne, the structures themselves are in process of demolition, and in the course of another month a large portion of the following streets will have disappeared:- Newport-court, Little Newport-street, Market-row, Market-street, Prince’s-row, Lichfield-street, Hayes-court, and Grafton-street.”

The last mentioned Grafton Street appears in one of the prints made in the early 1880s of Newport Market. The following print titled “North side of Newport Market Soho, Grafton St on the right”. The print is dated 1882, the same year as Grafton Street would be demolished – possibly a 19th century example of recording buildings and streets before their demolition.

Image credit: London Metropolitan Archives, City of London: catalogue ref: SC_PZ_WE_01_0315

The above view shows a rather good looking location. Open space edged by some well constructed buildings with shops along the ground floor. What the area may have been like can be judged by some of the newspaper reports of the time, such as the following from the Illustrated London News on the 10th February 1872, regarding the remains of a statue of King George II in Leicester Square:

“When the statue was removed, having suffered too much ll-usage and some positive mutilation, the effigy of the horse remained, and became the target of frequent stone-throwing practised by the idle boys of Newport-market and its neighbourhood.”

Returning to Sandringham Dwellings, the Metropolitan Board of Works were forced by the Government to construct dwellings for “2,000 people of the labouring classes”, in the area of Newport Market. Agreement to this allowed the Metropolitan Board of Works to commence demolition and the build of Charing Cross Road.

The dwellings for 2,000 people were comprised of the two blocks of Sandringham Dwellings that lined both sides of Charing Cross Road to the south of Cambridge Circus.

As was often the case with these new developments, it was probably not the displaced labouring classed that benefited from the new accommodation.

In the 5th September 1885 edition of the Illustrated London News, Police Superintendent J.H, Dunlap of St. James’s Division wrote “On the site of Newport Market, notorious for everything bad and disreputable, have been erected two splendid blocks of buildings for the accommodation of the working classes, one by private speculation and called Newport Dwellings, and the other by the Improved Industrial Dwellings Company, called Sandringham-buildings, a suite of erections of handsome elevation, with no appearance whatever of model buildings, having large shops on the ground floor, with the upper portion allotted in suites of two, three and four rooms. There is every possible accommodation and sanitary appliance. In these buildings, the Superintendent adds, he has sixty-seven police families, occupying 193 rooms.”

The following view of the remaining block of Sandringham Buildings is from the north, looking south along Charing Cross Road.

To show how identical the remaining block is with the demolished block opposite, compare the corner of the building with the corner photo I had taken in one of the photos at the start of the post.

The name plaque recording that the building was erected by the Improved Industrial Dwellings Company can still be seen on the northern corner:

Cambridge Circus is just under half way along Charing Cross Road from the north. It is at the point of intersection with Shaftesbury Avenue. it is named after the Duke of Cambridge who officially opened Charing Cross Road on Saturday 26th February 1887.

The Morning Post reported on the opening:

“The new line of thoroughfare formed by the Metropolitan Board of Works from Charing-cross to Tottenham-court-road, and designated Charing-cross-road, was on Saturday afternoon opened by the Duke of Cambridge. His Royal Highness was at one o’clock met opposite the church of St. Martin-in-the Fields by the members of the Metropolitan Board of Works, and thence drove along the new street to the circus forming the junction of the new thoroughfares.

Crowds had assembled on either side along the whole of the route, and at many points flags were flying from the windows of the houses. Upon reaching the circus the Duke of Cambridge alighted, and addressing those within hearing said – ‘I declare the new thoroughfare – Charing-cross-road – open for public use. I am happy to have the honour of assuring you and the other members of the board that all such improvements as these are of the greatest possible value (hear, hear). there is no question that the growth of this great metropolis has been such that the building of houses east and west through the town has gone on in a manner seriously injuring the public health, and anything the Metropolitan Board of Works or any other body can do to improve the locomotion in such a great city must be a benefit not only to the metropolis but to the country at large (cheers).”

The article also provides some statistics on the new road “The length of the new street is 966 yards, and its width generally 60ft. It widens to about 130ft at St. Martin’s-place but it is restricted at its entrance into Trafalgar Square to 45ft, between St. Martin’s Church and the National Gallery”.

The view across Cambridge Circus towards the Cambridge pub.

The most impressive building facing onto Cambridge Circus is the Palace Theatre, opened in 1891 for Richard D’Oyly Carte who intended the theatre to be the home of English opera and on opening the theatre was known as the Royal English Opera House.

As always, there is so much to see and explore, and I am only touching on a brief part of the history of the street.

The Porcupine pub on the southern corner of Great Newport Street, the building dating from around 1865.

Look on the corner of the building, a boundary marker is partly hidden by the lighting and flowers.

The old Tam O’ Shanter pub:

There has been a pub here since the mid 18th century, originally named the Bulls Head. The new building was part of the realignment and widening of Charing Cross Road and the new building dates from 1896, when the pub changed name to the name that still appears at the top of the building today. The Tam O’ Shanter closed as a pub in 1960.

Charing Cross Road is one of the locations where rumours of a hidden street below the surface persist. In the middle of Charing Cross Road, at the junction with Old Compton Street, there is a large grill on an island in the middle of the road.

Peer down through the grill and you can see a couple of signs for Little Compton Street on the brick wall lining the tunnel.

Personally I am not at all convinced that the wall and street signs are all that remains of a street from before the redevelopment of the area, now hidden below the surface.

For a start, in the 1746 map, Compton Street approaches from the west, and terminates at Hog Lane. In the 1847 map. Compton Street still approaches from the west, then Little and New Compton Street cross over and continue eastwards from what is now Crown Street. The wall below the surface is running north south, in the same direction as Charing Cross Road, not east-west as would be expected if this was a relic of Little Compton Street.

I am also not convinced that street levels along this part of Charing Cross Road changed this significantly during redevelopment to leave a substantial part of a wall buried below ground level.

Finally, the article I quoted earlier from the Morning Post on the 28th February 1887 probably gives the real reason; “A subway has been formed under the whole length of this street to receive the gas, water, and other mains, telegraph wires, &c.; it is placed under the centre of the carriageway, and is 12ft wide and 7ft, 9in. in height, formed of a semi-circular arch of brickwork.”

I suspect the street names may have been painted on the wall, or recovered from Little Compton Street and attached to the brick wall of the subway so that those working below ground, installing or repairing utility services would know where they were, as they worked their way, below ground, along the centre of Charing Cross Road.

As usual, I have only scratched the surface of the history of the area I visit to track down the location of our old photos of London. In a post a few years ago I wrote about Foyles and the College for the Distributive Trades to the north of the street.

Newport Market has long disappeared beneath Charing Cross Road and the buildings that now line the street, but the name can still be found in Newport Place, Little Newport Street and Great Newport Street – all references to Lord Newport who purchased the land in 1654 and who also gave his name to the market.

Interesting as ever. I was inspired to browse a little more into the background of Sandringham Buildings, and found a relevant Flickr post – https://www.flickr.com/photos/warsaw1948/6924276323 ; which refers to a 1966 Survey of London entry for the locality – https://www.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vols33-4/pp296-312 . As the Flickr discussion sadly illustrates, the demolition and redevelopment of Sandringham Buildings West seems to be the tale of our times.

Thank you so much for this. I live in the red 1979 block over the lost Newport Market and have never been able to find an image of the old dwellings that were demolished. Thank you for publishing yours. The history below me right now is fascinating so thank you for making it clearer.

Mark, there is a very brief location shot of the old flats at Newport Market in the 1935 film “Emil and the Detectives”. It really is fleeting but still gives a satisfying view.

The northernmost block appears to have been demolished after WWII damage but the other two blocks lived on. The film is of course pre-war but those are the two seen in the shot.

If I remember correctly, the film is on BFI’s player which has a free trial subscription. If you need help spotting the appearance of the flats, it’s just after the gang make their way across Piccadilly Circus.

Wasn’t Dobell’s under one of the Sandringham Buildings?

Yes it was indeed, otherwise the shop would never have moved

Fascinating photos and observations. Love the then and now photos.

Really excellent article. I am trying to trace the history of a wallpaper shop at no’s. 5 and 12 Old Compton Street named “The Compton Wallpaper”. It was established in Soho in 1870. Also very interested in Sandringham Buildings. My Dad took me to visit a couple who lived in Sandringham Buildings about 75 years ago. I believe they were a Mr and Mrs FERRIS. I also think he may have been a policeman, therefore your mention of the Superintendent saying he had police families living in the building is of great interest. This couple moved down to live in Gloucester. I went to stay with them for a holiday about 1948, they took me to visit Gloucester Cathedral, starting my life long love of cathedrals. I would love to find out more about them.

Great comments there must look out for Emil and the detectives , interesting as usual.

Excellent feature. As a person who worked originally in the neighbourhood (New Theatre and Wyndhams, I spent a lot of leisure time in or near this location (porcupine pub, lamb and flag, brewmaster and the Salisbury) as well as Bunjies folk club).

Ultimately I became a resident just off seven dials, and got to know the neighbourhood very well.

This week’s feature brought alive all my fond recollections of the area.

Thank you for the most comprehensive and informative article.

As a previous commenter mentioned, the two Dobell’s shops were there, at 75/77 Charing Cross Road, the Folk Shop and Jazz Shop next door to each other for many years (before moving to Tower St when the building came down). In 2013, there was an excellent little exhibition at the Chelsea Arts School, tracing the shops’ history, with lots of photos, ephemera etc, including their famous old carrier bag with the display of record spines. There’s some good photos of the shops around the web, and Doug Dobell has a Wikipedia entry.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Doug_Dobell

Fascinating post – I grew up at 121 Sandringham Flats (as we called them), from 1960 til 1980. I remember that Tariq Ali lived in the flats at some point, and that Ida Barr, the music-hall star, lived on our staircase – I would sometimes go and have tea with her. The Dobells, Glad and Doug, lived in the flat underneath. We both had the corner flats, above Zwemmer’s bookshop, and our kitchen was on the Litchfield Street side, looking towards The Ivy and the St. Martin’s Theatre.

Hi Martin, did you know Ida Miller who lived in 107 she was my great nan. She died in 1977.

Hi Rosie – I knew Ida Barr, is that the same Ida?

Hi Martin

Would you remember a lady Phyllis Parker Price, a Welsh lady? She was my Great Aunt and lived in Sandringham Flats for nearly 30 yrs until her death in 1986. She moved between numbers 136 and 137. I never met her and would love to know if someone remembered her.

Julie

Hi Martin

Do you remember a Welsh lady called Phyllis Parker Price? She moved between flats numbered 136 and 137? She died in 1986, lived there for many years I believe.

Would love a reply from someone who lived in the Buildings 1950s to 1980s. My great Aunt lived 136 or 137 for nearly 30 yrs.

I don’t actually remember Phyllis, and now my mum has gone there’s no one left to ask — sorry, Julie.

Thanks for reply. She had a baby adopted in 1948 no one in family knew about, my Mums first cousin found due to dna last year. Trying to help this new elderly family member. All we know is that Phyllis lived in Sandringham Flats until her death in 1986.

There is a building on the corner of Charing Cross Road and Denmark Place that is called Shaldon Mansions over the door on the Charing Cross front but the name over the door on the Denmark Place side is Halberstadt Mansions, dated 1889. I wonder if they were renamed in 1914 as anything with a German names was considered unpatriotic.

I’ve found an 1859 wedding certificate for my great grandparents who were living at 8½ Cambridge Circus. Has anyone any idea where that would be now and why the peculiar numbering?

My second Great uncle, William Elliott, an Inspector in the London Metropolitan Police, is recorded in the 1891 England Census as residing at Sandringham Buildings Block 1, No. 2, in the civil parish of St Anne.

Can anyone clarify which block was Block 1 and if it still exists?

If it was in the parish of st Anne’s then it would, I believe, have been on the west (Soho) side of Charing Cross Road.

On the other hand, Kelly’s Post Office Directory for 1895 gives this at street numbers 56-58 Charing Cross Road (east side):

Sandringham Buildings, entrance Nos. 1 to 74.

The same flat numbers show on OS 1951, split between 1-50 at street numbers 56-58, and higher flat numbers further up the street.

In Kelly’s 1895 the flat numbers for the west side are given as 170-259, with OS 1951 in agreement.

OS maps appear to show that the parish boundary does a detour along West Street, Upper St Martin’s Lane and Great Newport Street, regaining Charing Cross Road outside The Porcupine pub.

If all of the above are correct then flat 2 in block 1 would be in directly above the shops on the east side of Charing Cross Road, with the block entrance immediately to the right of Henry Pordes Books.

Google Maps > Satellite > Global View offers a good “back” view of block 1.

Best of luck to Trevor in finding out more.

Thank you for that information. I will need to loo at it carefully when I have time.

I used to live about 350 yards away from the address in question and never knew that St Annes parish encroached onto the east side of Charing Cross Road. The bookshop (with the green paintwork) featured in a well known TV advert about a man phoning around looking for a particular book – clearly before the internet.

The Porcupine was an occasional haunt of mine – as I worked for a time in the New Theatre and Wyndhams Theatre nearby.

The TV advert promoted Yellow Pages, and the book was ‘Fly Fishing’ by J R Hartley. ‘Hartley’ was the man phoning round and trying to locate a copy of his own book. I still have a copy of the spoof novella that was published under that title in hardback in 1991.

HI I’m resident currently in the block and used to help run the residents association. The wife of the last manager of Dobells now lives here so everything has come full circle. She has some great pictures of the area including the sadly demolished block across ths street. Martin if you are reading I think I may actually live in your old flat!

Another view of the demolished bullding can be seen in an episode of the professionals TV programme. Older residents will remember the rooftop water tanks and the black metal fencing that had survived the war and existed until a few years ago as the block was modernised. The very steep steps that used to grace the floors have now been widened! The small gate on Great Newport street can be seen in the Harry Potter film briefly. I’m pleased to say that some of the bookshops remain but sadly Zwemmers shop is now gone replaced by an art gallery.

My great nan lived in Sandingham buildings my nan grew up there too until see married my grandad in St Martins of the field. My great nans parents also lived in Sandingham buildings. I remember going to see my great nan as a small child and I remember the small front room. I was 5 when she died in 1977. I recall walking up the spiral staircase to her flat. I often think about being able to get in touch with the residents who live in my great nans old flat today and see how much it must of changed. My Mum would like it too as she adored her nan.

Hi Stephen, that’s extraordinary to think that it all still exists. 121 was at the top of the (in my day) stairs — “These stairs have Winders” was the sign at the bottom! We had a tin bath on the roof in one of the small huts that were there. I seem to remember that it was 1971 before we had an inside bath. I recently found some photos that we took on the roof. My dad had shopfitted Doug Dobell’s first shop in Kemptown, Brighton, in 1956, and when Doug moved back to London and got a flat opposite the shop, he tipped us the wink, so we ended up living above Glad and Doug for about twenty years.

That was a welcome update. I spent a lot of my misspent youth (and twenties) around that area, having worked at the New , wyndhams and garrick theatres, frequented bunnies folk club and lived just off seven dials. Thank you

This is a very informative post – Thanks!

My interest is in Litchfield Street, where family members lived at Nos 17 and 23 in the 1860s. Those at No 23 had moved a few streets away by 1871. I now guess this was because they were removed in advance of the demolishing of the north side from no 23 westward!

But why was the decision made to demolish the west side Sandringham Buildings? It couldn’t have been bomb damage during the war, as they were still in existence by 1979. Why weren’t they just restored and improved? And what of her sister buildings across the road? Were they too earmarked for demolition also?

I lived in the now-demolished Sandringham

Flats as a child, moving out in 1971. I lived there with my mother and then my grandmother moved in. We were in Flat 231. It was a tiny flat, accessed by a communal spiral staircase at the back of the block. You could hear people’s footsteps walking up the stairs from the bedroom. There was a toilet but no bathroom – you had to wash your hands in the kitchen sink. My mum and grandmother used to go to the baths at The Oasis swimming pool. I was small enough that I could be bathed in the kitchen sink. It was a fairly warm flat as we got the heat from the shop below (which was a dress shop, from memory). My grandmother stayed there when my mum and I moved out when my mum remarried. My grandmother was rehoused in Luxborough Tower in Luxburough Street, off Marylebone Road when the demolition of Sandringham Flats was on the cards. I was about 9 or 10 when we moved out so my memories of the block are a bit dim, but it was home to me for a big part of my childhood. I never understood the reason for knocking down one side of the Charing Cross Road flats, but not the other. I find the new red brick flats very much out of character with the rest of the area.

My Great Aunt lived in Sandringham Flats from late 1950s to her death in 1986. I never met her but have had her 1935 Book of Common Prayer handed down to me. I visited the area last month and found the imposing building.

Does anyone remember her pse- Phyllis Parker Price, a Welsh lady. She lived for some years there at number 136 and for some reason moving to 137( or vice Versa)

Do you know if there was a poor house called Charing Cross Union around 1898 on Charing Cross Road ?

The only poor house in that general location, of which I am aware, was the St Martin’s Workhouse which operated between 1725 and 1871. I was located by St Martin’s Place near the current location of the National Portrait Gallery.

So many people wondering why the West side block was demolished and the answer is simple but sinister. It was part of Dame Shirley Porter’s plan to move working-class Labour voters out of the area and replace them with white-collar workers who would help the Tories retain control of Westminster Council. It worked, but later adjudged to be Gerrymandering, and she was ordered to pay £42 million. It’s all on her Wikipedia page – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shirley_Porter