The City of London has always been a busy and congested place. For centuries, gardens and green space were only to be found around the halls of the Livery Companies and the gardens of some of the larger houses owned by rich City merchants and well connected residents.

As trade, manufacturing and finance expanded within the City during the 19th century, open space was not treated with the some level of priority as buildings that served the commercial purposes of the City.

Significant destruction of buildings and damage to large areas of land during the war resulted in new thinking as to how reconstruction should take place. I have written about a couple of plans for the City such as the 1944 report on Post War Reconstruction of the City, and the 1951 publication, The City of London – A Record Of Destruction And Survival.

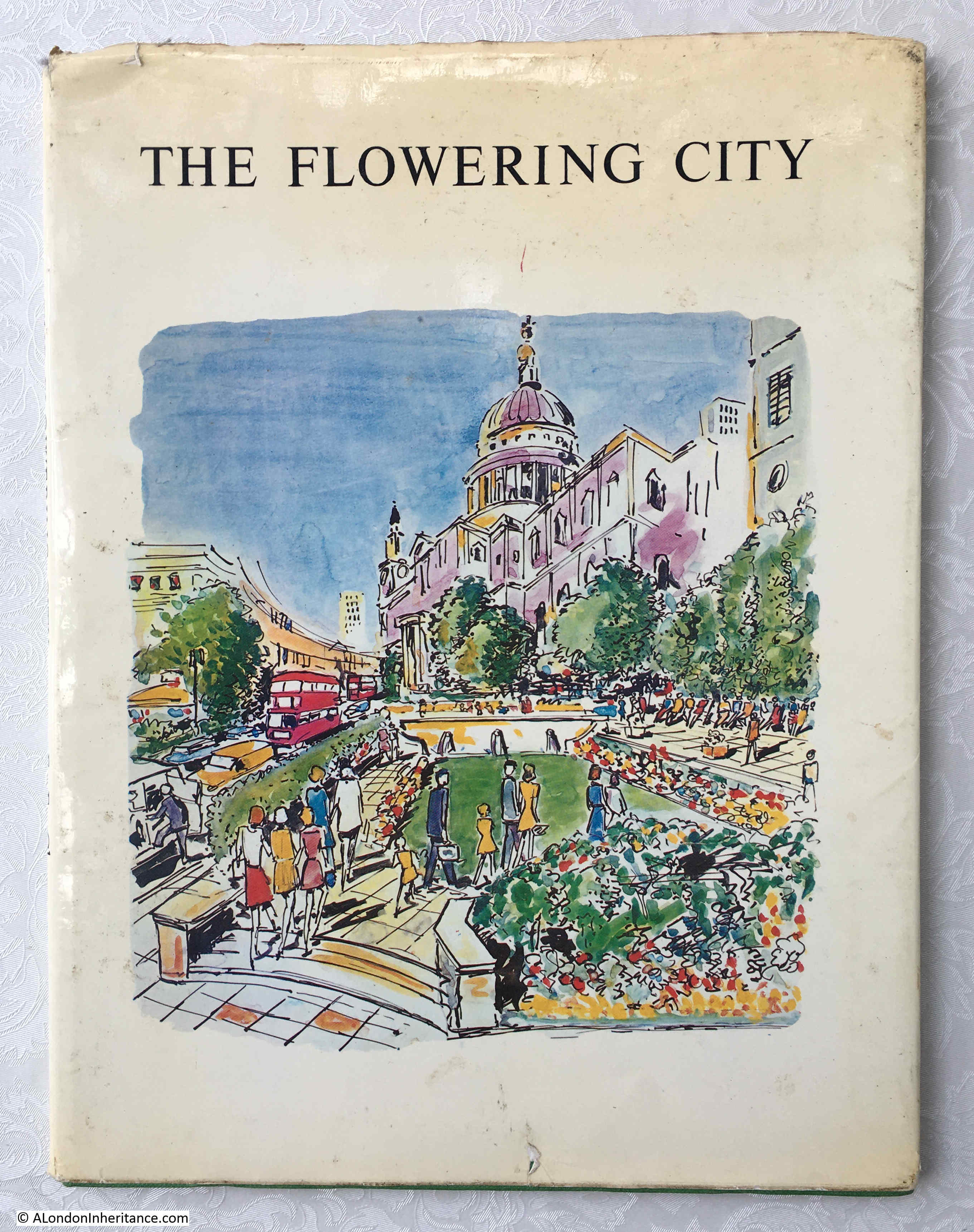

More green space, places for people to sit, and the planting of flowers was one of the initiatives pushed forward by Fred Cleary, and in 1969 he published a book about the new gardens in the City titled “The Flowering City”:

Fred Cleary was a Chartered Surveyor who worked for a City mortgage and investment company. He was also a longtime member of the City’s Court of Common Council, and according to the author information in the book was Chairman of the Trees, Gardens, and City Open Space Committee, and the Chairman of the Metropolitan Public Gardens Association.

The aim of the book was to “record something of the considerable efforts made by the City Corporation who, supported by many business interests and voluntary bodies, have endeavoured to make the City of London one of the most colourful and attractive business centres in the world.”

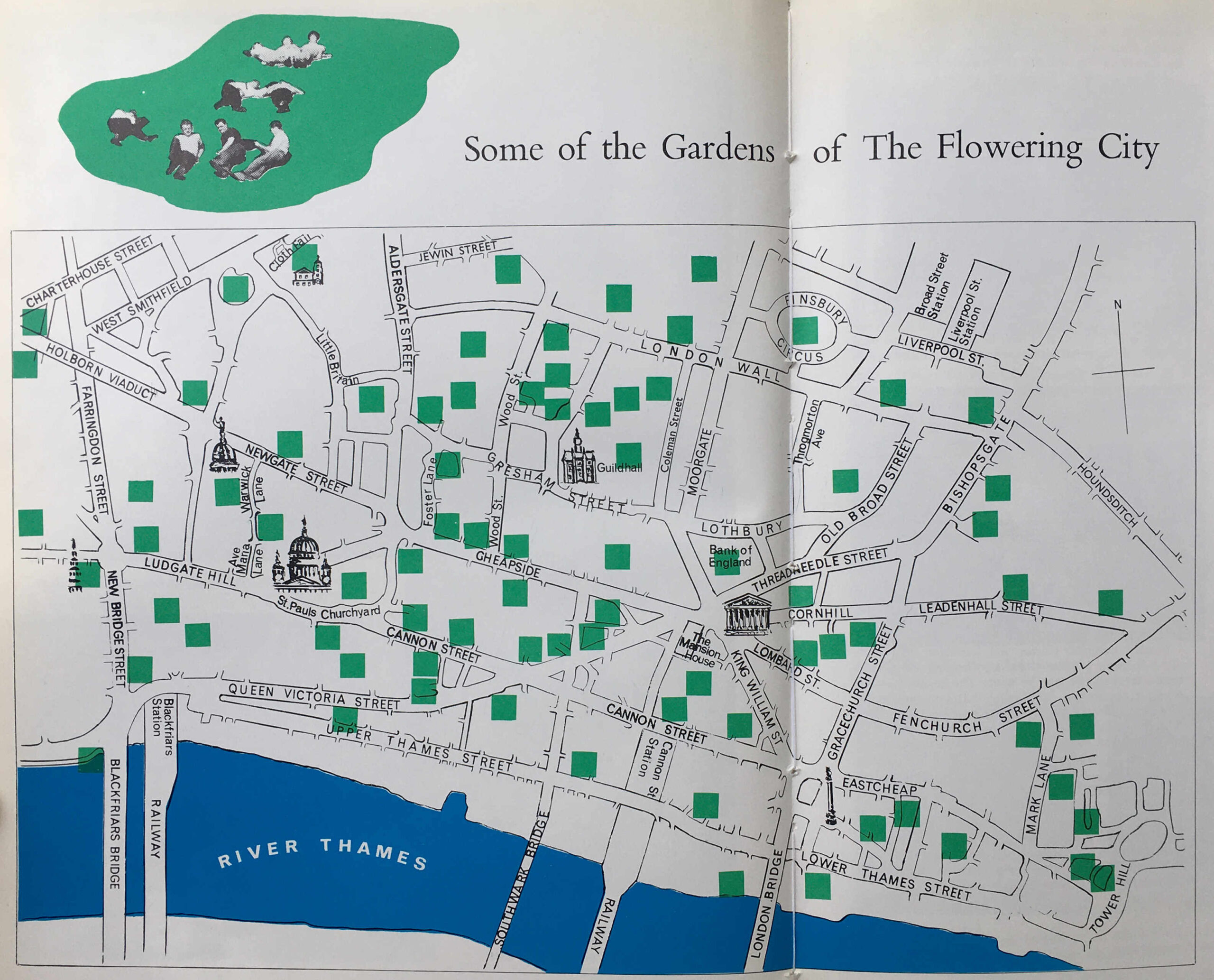

Through his interests and his membership of a number of key City committees, Fred Cleary had a leading role in the post war development of many of the gardens across the City, and the book includes a map of some of these gardens, many of which feature in the book:

The book is full of photos of the first gardens to be created as the City reconstructed after the war. Many of these gardens still remain, although they have changed significantly over the years.

Originally, they had a rather formal layout with basic planting. Today, many City gardens are far more natural with lots of planting and almost a wild feel to some of the best.

What I think is the very latest City garden almost looks straight from the Chelsea flower show and has an incredible central water feature. I will come to this garden later in the post, but the first garden on a brief walk to some of the City gardens, was the one named after Fred Cleary.

Looking south, across Queen Victoria Street, and we can see the start of Cleary Gardens:

One of the entrances to Cleary Gardens from Queen Victoria Street:

A long brick pergola facing onto Queen Victoria Street with seating between each of the brick columns:

Many of the new post-war gardens were built on bomb sites, and Cleary Gardens occupies such a site. The land drops away to the south of Queen Victoria Street towards the Thames, so the gardens are tiered. Walk down to the middle tier and there is a small enclosed space:

At the end of the above space, there is a blue City plaque on the wall, commemorating Fred Cleary who was “Tireless in his wish to increase open space in the City”.

The remaining walls from the buildings that once occupied the site have been included in the structure and tiers of the gardens:

Cleary Garden was initially planted by a City worker in the 1940s and on the evening of the 26th July 1949, the garden was visited by the Queen (mother of the current Queen) who was on a tour of City and East London gardens.

The gardens were significantly remodeled in the 1980s and it was following this work that they were named after Fred Cleary who had died in 1984.

The lower tier of the gardens:

Huggin Hill forms the eastern border of the gardens. Excavations at the gardens, under Huggin Hill and under the building on the left have found the remains of a Roman bathhouse.

Fred Cleary argued not just for open gardens and green space, but also for more planting of flowers across the City, and an example of what he would have appreciated can also be found in Queen Victoria Street, outside Senator House, where the office block is set back from the street, and raised beds full of flowers have been built between building and street:

Almost all of the City gardens featured in Cleary’s book have been remodeled several times since their original construction, and those in the book look very different to the gardens we see today.

Hard to keep track with change in the City, but I think the very latest example of how gardens change are the recently reopened gardens on the corner of Cannon Street and New Change.

There have been gardens on the corner of these two City streets for many years. The gardens were last redesigned in 2000 based on a design by Elizabeth Banks Associates, however they recently reopened following another major redesign.

These gardens are in front of 25 Cannon Street, and Pembroke, the developers of the building included a transformation of the gardens by the landscape and garden design practice of Tom Stuart-Smith.

I must admit to being rather cynical of many new developments which are aligned to an office project. Too often they are a low cost bolt on, designed to make the planning process easier, however these new gardens are really rather good.

The key new feature at the centre of the gardens is a large reflection pool:

The pool was the work of water feature specialist Andrew Ewing. The water in this pool is very still (although it does appear to be flowing over the internal edge), and is positioned to provide some brilliant reflections of St Paul’s Cathedral:

The outer wall of the pool provides seating, and the surrounding gardens are planted to such an extent that the traffic on the surrounding streets is effectively hidden.

Although good for taking photos, I was surprised that on a warm and sunny June day, very few people walked through the garden or used the seating. Not easy to see the central pool from outside the garden, but it is very much worth a visit.

View across the central pool to the buildings of One New Change – the mature trees from the previous development have been retained, and the central layout and smaller planting is new:

Possibly one of the reasons why the above gardens were so quiet is the large amount of open space and gardens across the road around the south side of St Paul’s Cathedral.

These gardens were all part of the late 1940s / early 1950s development of new green / garden space, but have become more planted since.

The garden’s in the 1960s were rather basic green space, as shown in the following photo from The Flowering City:

The office blocks in the above photo have long been replaced, and the only recognisable feature in the photo is the church of St Nicholas Cole Abbey in the background.

The garden consisted of mainly grass with some planting in the centre and around the edge.

Today. the gardens are very different with plenty of planting and some works of art:

Plants, hedges and walkways:

Looking towards the City of London Information Centre:

City gardens tend to be very well maintained and the gardens to the south of St Paul’s were being worked on during my visit:

Across the road from the above photos to the immediate south east of St Paul’s Cathedral, there is another large area of green space:

These gardens have changed the area considerably, and have been through a series of post war development.

The following photo is one of my father’s photos from the Stone Gallery of the cathedral. The church in the photo (minus the spire), is the same church as seen in the above photo.

The space occupied by the gardens to the south east of the cathedral were once a dense network of streets and buildings as can be seen by their remains in the above photo.

My comparison photo to my father’s is shown below – a very different view:

The gardens in the above photo were the first to be constructed in 1951 to tie in with the Festival of Britain, and go by the name of Festival Gardens. The book Flowering City shows the gardens as they were originally built:

The gardens seen in the above photo remain, however the gardens have been extended all the way back to cover the road and circular feature at the top of the photo and the road to the right.

These original gardens and the three fountains are very much the same today, as can be seen in the following photo:

View back from the top of walkway behind the fountains:

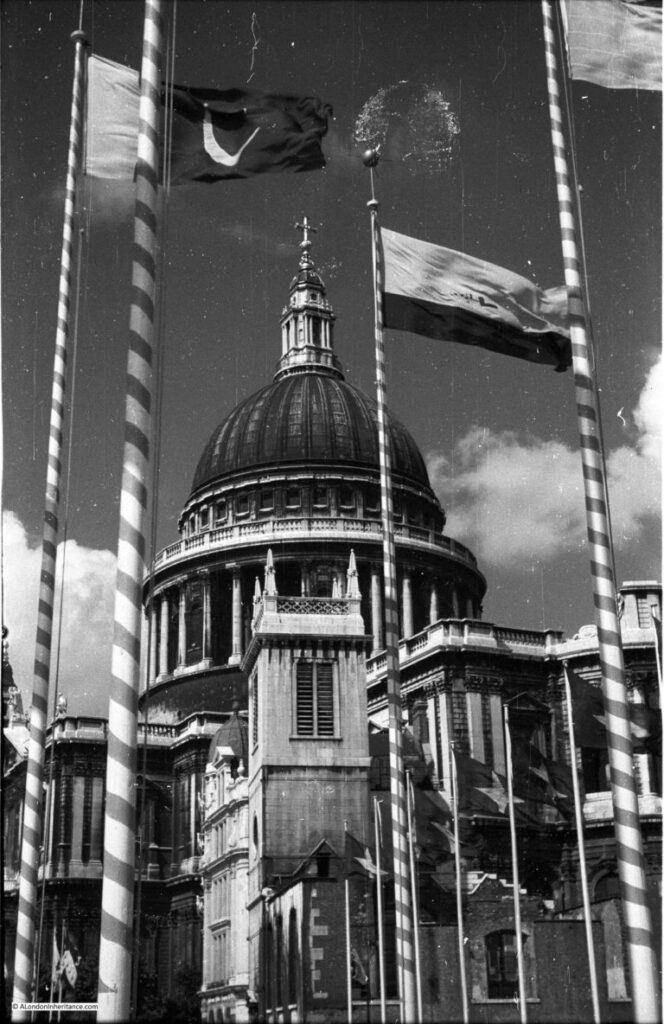

This original part of the gardens were timed to open for the Festival of Britain (hence their name), and were decorated with flags during the festival as shown by my father’s photo below:

Plaque on the wall commemorates the year of opening:

And another plaque on the wall behind the fountains records one of the ancient streets that were lost during the construction of the gardens:

As well as large, formal gardens, Fred Cleary was keen to encourage the use of flowers in as many settings as possible, and devoted four pages to photos of City buildings with window boxes.

I found a number of these adding colour to City streets:

Many of the window boxes across the City in the 1960s were the result of a campaign, as described in the book:

“In 1963 the Worshipful Company of Gardeners in conjunction with the Metropolitan Public Gardens Association and supported financially by the City Corporation launched a ‘Flowers in the City’ campaign under the patronage of the Rt. Hon. The Lord Mayor and in recent years there has been considerable response from the business houses and firms by providing more and more flowers giving a very colourful effect to many parts of the City.”

As well as windows boxes, the book encourages the planting of flowers across the streets and includes a section titled “Pavement Treatment” which shows how plants can be distributed across the streets in pots, wooden boxes and within raised concrete walled beds. The aim was to add flowers and colour to as many points across the City as possible.

An example of the type of planting featured in the section on “Pavement Treatment”, can be seen today at the junction of Cheapside and New Change:

At the start of the book, it mentions that originally gardens in the City were mainly part of Livery Company sites, or surrounding some of the more expensive houses in the City.

There are still a number of gardens on land owned by Livery Companies. One of these is at the junction of Copthall Avenue and Throgmorton Avenue and is on land owned by the Drapers Company who have their hall in Throgmorton Avenue.

The gates to the garden are locked, however peering through the gates delivers this colourful view:

The book also shows just how much areas of the City have changed. In the following photo, the wall to the left is the medieval wall that sits on top of the original Roman wall, just to the north of London Wall, close to the Barbican development:

When the area around the wall went through its first post-war phase of development, it was surrounded by new office blocks and the high level pedestrian ways that followed the wartime proposals for City redevelopment which included below ground car parking, wide streets for car, and raised walkways to move pedestrians away from traffic.

The photo below shows the wall surrounded by the first phase of post-war development. Note the shops and pedestrian ways to the right.

What looks like the original route of London Wall is in the lower right corner of the photo. This is now a walkway with the route for traffic moved slightly south as the dual carriageway routing of London Wall.

A small section of gardens is between the wall and street.

The medieval wall is the only feature that remains today from the above photo.

The area today is landscaped with gardens where the steps and building in the background of the above photo were located, and the medieval walls of St Mary Elsing have been fully exposed:

The City of London has benefited considerably from the work of Fred Cleary, and the book shows just how much was achieved to green the City during immediate post-war redevelopment, and the very many photos in the book shows how much the City has changed since it was published.

Fred Cleary was awarded an MBE in 1951 and a CBE in 1979 for his environmental and philanthropic work. He was also active in building conservation.

The Cleary Foundation was a charity established in his name, and today continues to provide grants to fund projects in the areas of Education, the Arts, Conservation, and the Natural Environment.

The majority of the gardens in The Flowering City remain, and many have developed from a formal simplistic style, to more heavily planted, and attempt to isolate the garden experience from the surrounding streets.

Fred Cleary dedicated the book “To all who live and work in the City of London”, and there can be no doubt that the gardens across the City enhance the experience of living and working in this historic place.

I’ve ways wondered what that circular feature was near St Paul’s, it looks like something below ground level, some ruins perhaps, very intriguing

Beautiful, thank you

The 25 Caoon St development is a reclad if the existing buiding, dropping the heavy PoMo styling and opening up the ground floor for retail. The garden hasn’t chnaged that much and I suspect it’s the very mature trees you note that tend to disguise its presence. The wall doesn’t help, albeit it’s very well made.

Very interesting post thank you

Fred Cleary’s country home was The Pines at St Margaret’s Bay on the coast of East Kent, between Deal and Dover. The Pines Gardens were developed in the latter part of his life and flourish as a charitable concern to this day.

One day I am going to walk through the City simply to visit as many gardens as possible. I am always struck by the window boxes and how they have improved the streets. BTW if you cross to the south bank and walk along from Bermondsey Wall to the Angel at Rotherhithe you will see a new garden that has been made. Very pleasing to behold.

Cleary started as a Hornsey councillor and we owe him for some lovely small flower beds in Muswell Hill Crouch End and Stroud Green installed in the 1950s as part of postwar reconstruction. Most are still there and there is a lovely 1960s film made by Hornsey showing off their beauty.

Little bits of heaven in a busy city. Always loved the Gardens like Soho Square etc.

Being a gardener my self this was a most interesting article.

This was a most remarkable and fascinating piece. Thank you so.much! You have inspired me to get out of the house and try to discover some city gatdens. Thank you, again!

Another fantastic and informative Sunday read, many thanks for what you do !!!

Really enjoyed reading this – I look forward to your posts . Fascinating stuff. Thank you.

Large numbers of open spaces in the City were not the result of bombing, but were very old graveyards, closed because of overcrowding, and re-purposed as gardens by the Metropolitan Parks and Gardens Association in the second half of the 19th century. That splendid association blazed the trail that Mr Cleary followed so actively in the second half of the 20th century. I do hope there’s a Cleary equivalent working away right now! We all need as much green space as possible. THANKS so much for this lovely post. I didn’t know about two of the gardens you mentioned, so was glad to learn about them…. and I always love to see your father’s photos.

This article has been brought to my attention as I am the current Chairman of the Cleary Foundation started by Fred Cleary and I am honoured , as a fellow Chartered Surveyor, to hold the chair and assure you that the Foundation has survived and in some small way we do follow the path of grants to causes that were in his heart.

A very interesting article. The latest count has over 170 open spaces within the Square Mile which are the responsibility of the City Gardens team. In addition, there are many private gardens and other gardens, like 25 Cannon Street which is “public” but privately maintained.

Two points though. Shouldn’t reference to St Mary Elsing be to St Alphage? Also, the reflective pool at 25 Cannon Street is the enable the basement underneath to enjoy natural light. I understand the water is treated and filtered so of no benefit to wildlife.

Thanks for this post, I had long since forgotten the once familiar name of Fred Cleary, a friend of my father’s.They both attended Owen’s School and studied at the North London Polytechnic. Both had reserved occupations during the war, as chartered architect and chartered surveyor. Together, they designed and built the new Sports Pavilion for Owens Playing fields in Whetstone, long before the school moved to Potters Bar.