It is the late 1950s, and you are a resident of the village of Hook in north Hampshire. Surrounded by countryside, London seems some distance away, although the village has a direct railway route to Waterloo, and the A30, then the main road from London to the south west runs through the village.

Although London is roughly 40 miles to the east, decisions made in London, by the London County Council threatened the village of Hook and the surrounding countryside with the imposition of a New Town that would bring thousands of people and dramatically change the whole character of the place.

I have long been fascinated by the impact that London has on the rest of the country. There are many different examples of this, one of which was the post-war move of population from the city to the surrounding counties, and the development of new towns.

The proposals for Hook New Town did not make it through to construction, however they did raise significant concern in the area affected, and they also show L.C.C. thinking about how new towns should develop, and how people would want to live in the second half of the 20th century.

The London County Council were supporters of the New Town movement, and although their plans for Hook did not get implemented, they published their design work in 1961, and in the forward of the book, “The Planning of a New Town”, Isaac Hayward, Leader of the Council, wrote “I believe that Britain still needs more new towns, and the Council publishes this book in the hope that the Hook studies will be useful to those who have the good fortune to be called on to plan them.”

The L.C.C. had been searching for a site for a new town, able to support a population of 100,000 for two years before finally deciding that Hook was the best location and met their key requirements, which were:

- Does not have a high agricultural value

- Can be adequately drained

- Sufficient water for the town could be produced

- Excellent road and rail communications

- Attractive to industrialists, whom it was hoped, would move out of London to the new town

The last requirement was considered to be the most important.

The search area had been south east of a line drawn between the Wash and the Solent. Above this line, the L.C.C. considered that a town would come under the “pull of Birmingham”, but south would be under the “pull of London”. An interesting example of just how far the L.C.C. believed came under London’s influence.

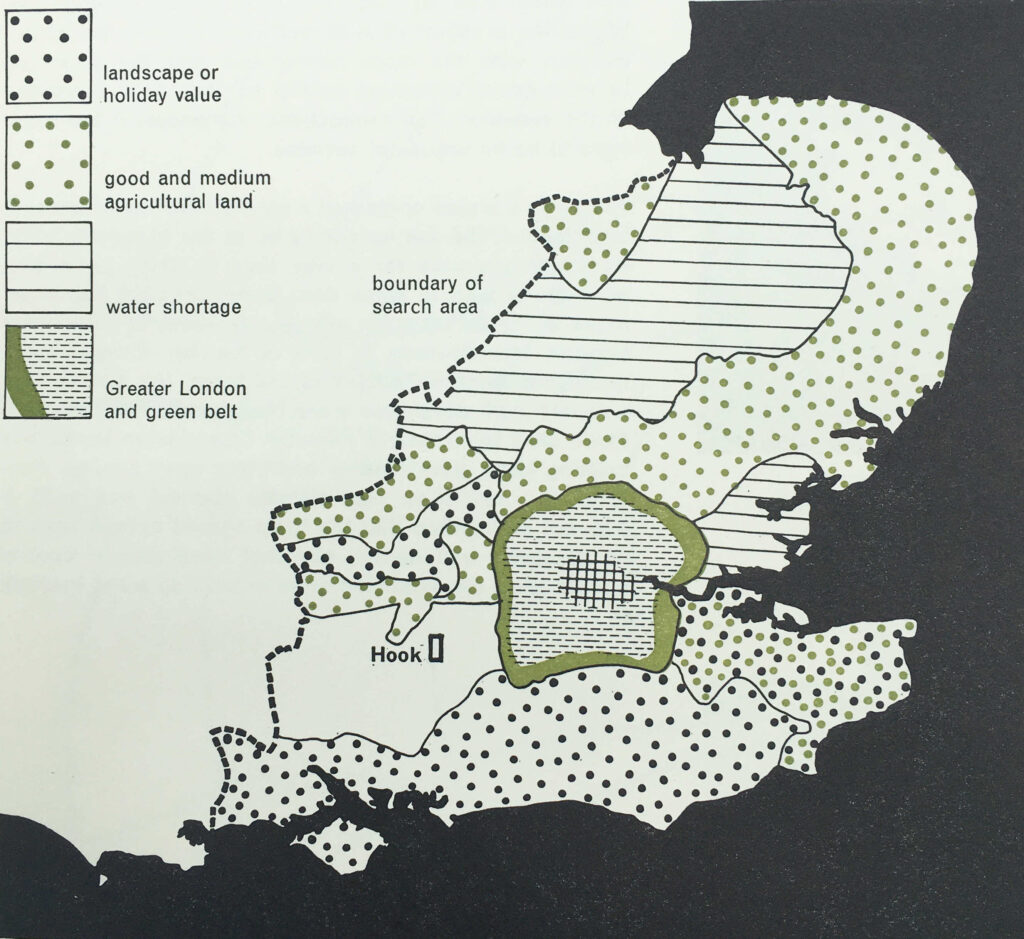

The following map from the book shows the search area limitations and the location of Hook:

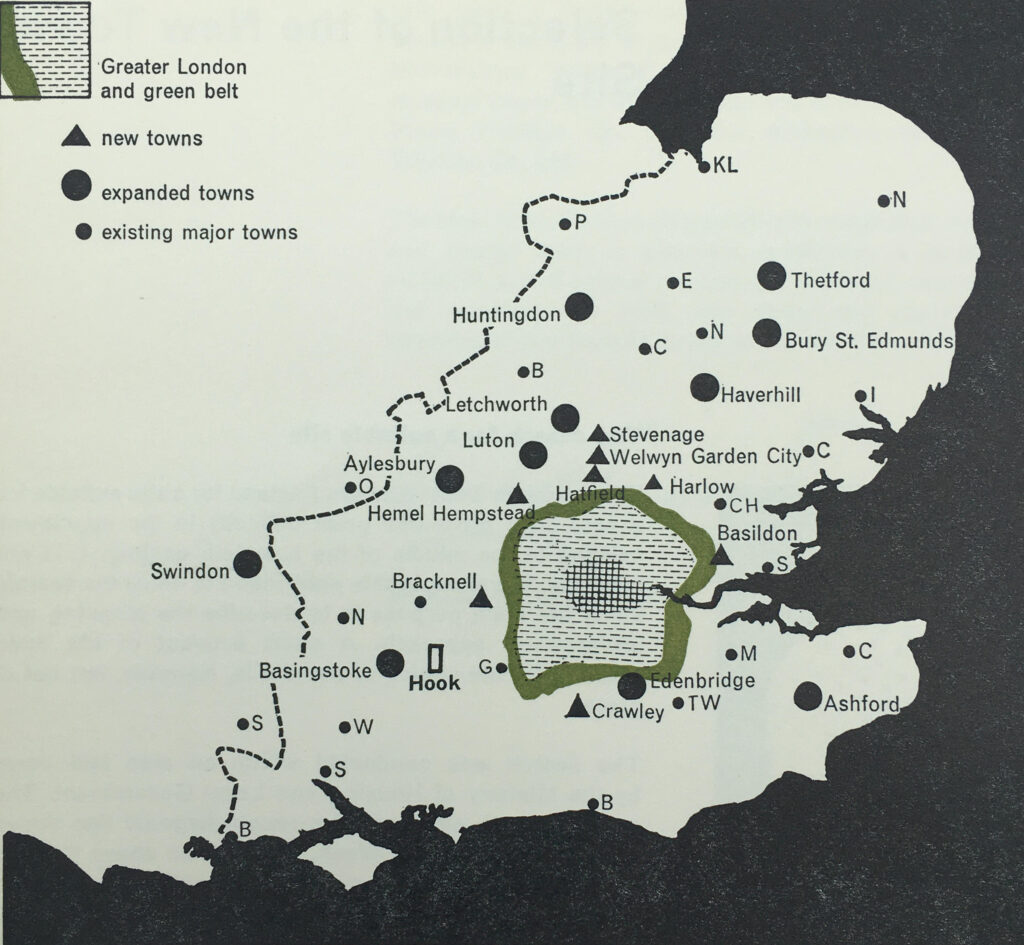

The site also had to take into account the location of other new and expanded towns. The post-war period had seen considerable growth across the south east of the country, mainly driven by the shift of population and industry from London to the surrounding counties.

As well as the criteria listed above, the search also had to ensure that the new town was not too close to other new and expanded towns and would not merge into other centers of population.

The following map from the book shows the new and expanded towns surrounding London, with the new towns of Basildon, Harlow, Welwyn Garden City, Stevenage, Hemel Hempstead, Bracknell and Crawley, all orbiting just outside London’s green belt.

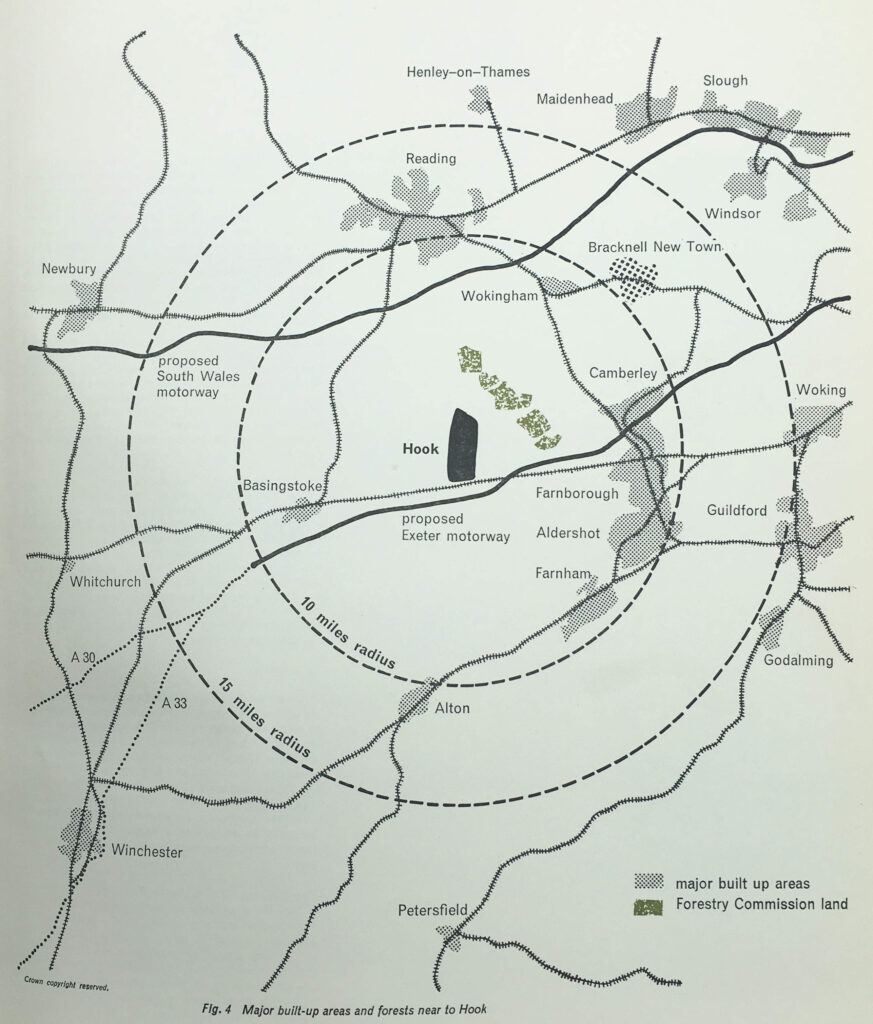

Transport links were also important, but not for commuting into London. Whilst Hook had a good rail connection into London, planning for the new town made clear that it was not intended to be a dormitory town, with large numbers of residents commuting into the city.

Good transport was a requirement to attract industrialists to the new town, and Hook had the benefit of being close to two new proposed motorways.

As well as new towns, post war planning included the web of motorways that now reach out from London. Two proposed at the time of the Hook plan, and shown on the following map were the “South Wales Motorway”, now the M4, and the “Exeter Motorway”, now the M3.

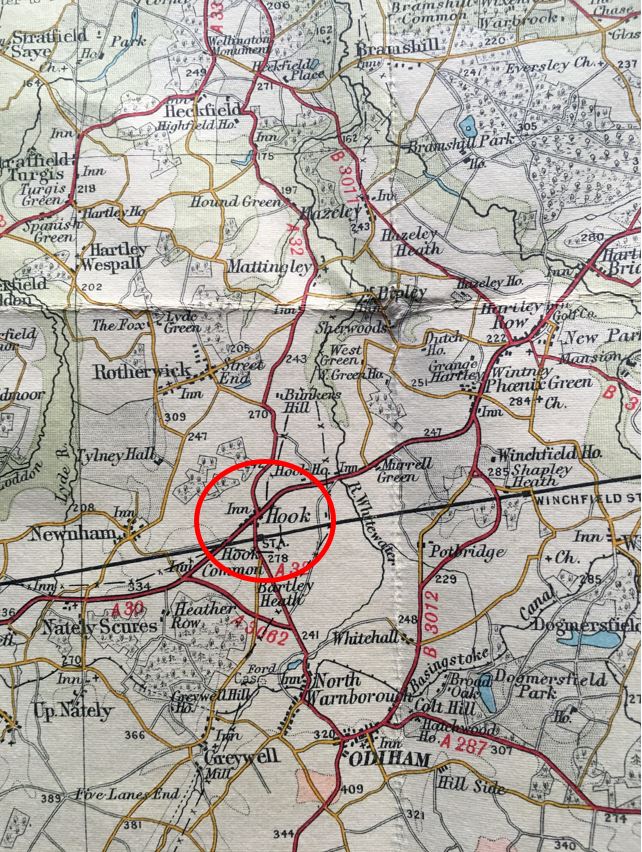

To get an idea of the rural location of Hook, the following map is an extract from a pre-war Bartholomew’s map of Berkshire and Hampshire, and shows Hook circled:

At the time, Hook was a very small village. A couple of old coaching inns which had served traffic on the A30 which ran through the village, and limited development along the line of the A30.

The coming of the railway to Hook had led to some expansion, and the village has seen much larger development in the last few decades, and now has a population of around 8,200.

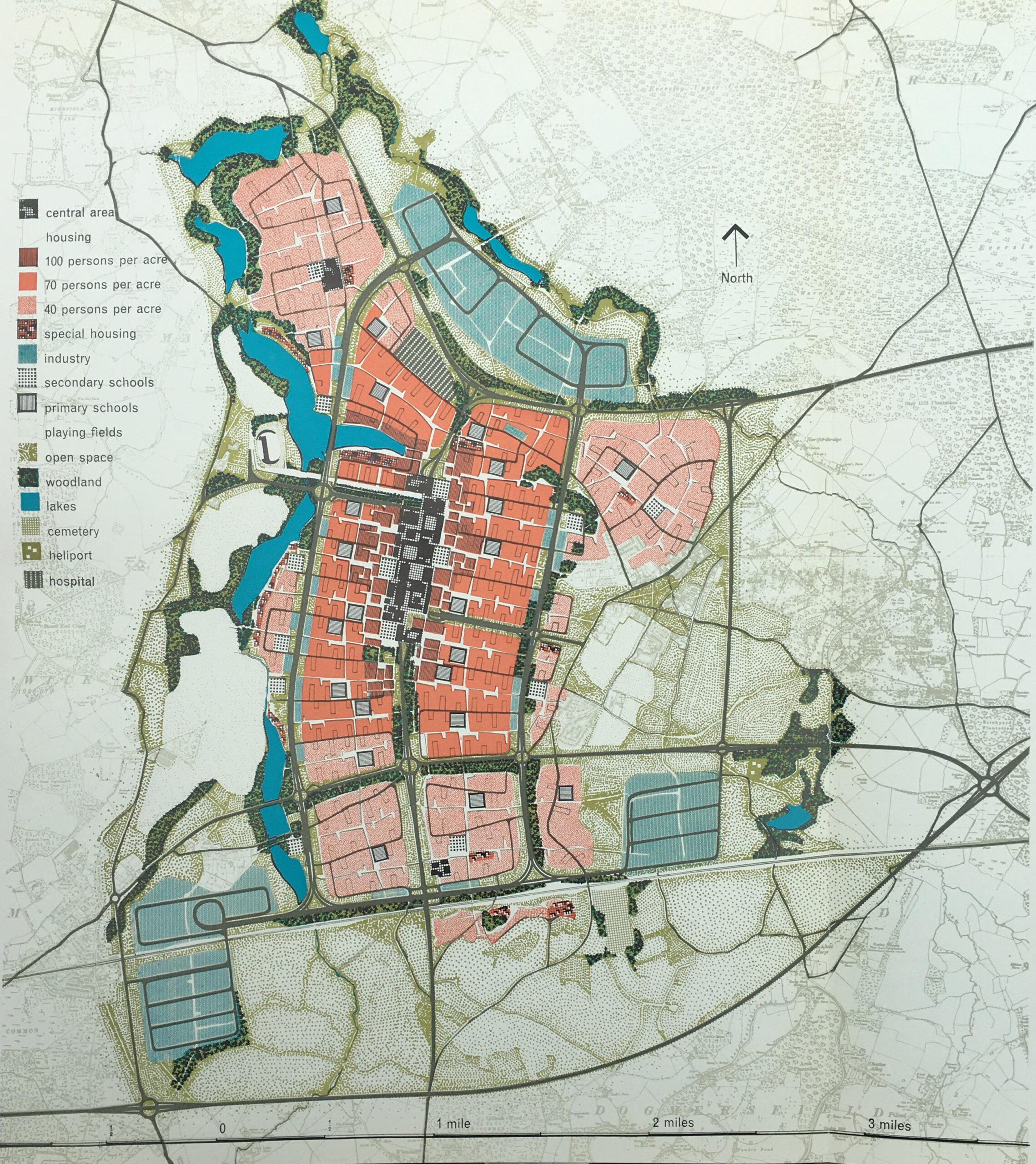

The L.C.C. plan for Hook covered a 50 year period of development, and the layout of the town after 50 years, with the full population of 100,000, with surrounding industrial zones is shown in the following Master Plan:

The key to the left of the above shows how the site would be used. A central core area, with reducing density of people per acre as you move from the centre. Industrial, green space and lakes surrounding the core.

The plan had a 1950s view of what the future could look like, as the town also had a heliport.

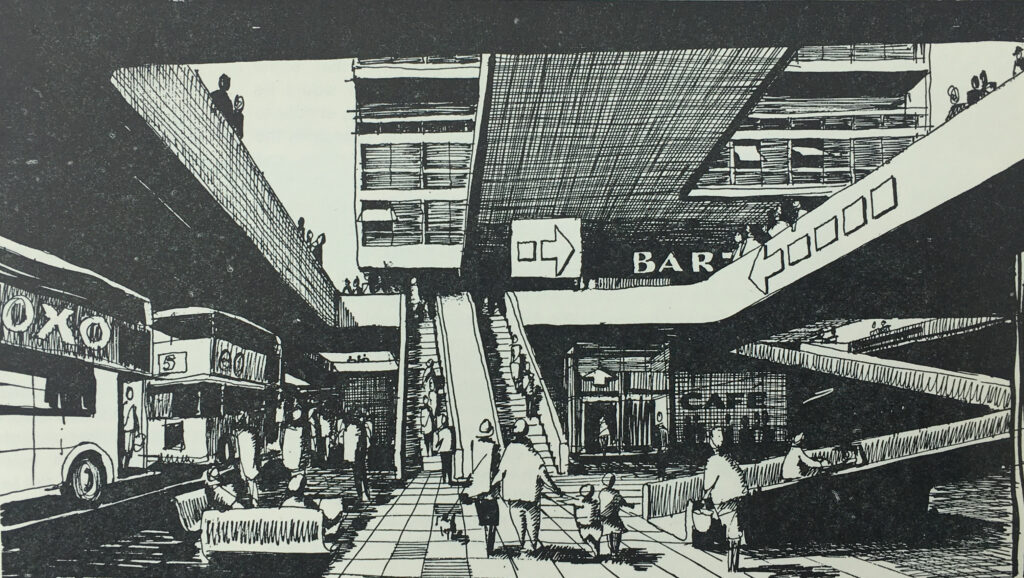

The plan for Hook included some of the ideas from post-war development of the City of London. The plan included the separation of pedestrian and vehicle traffic, and the central core of the town was to be built on a platform, free of vehicles, but containing under it and on its approaches, provision for the movement and parking of 8,150 vehicles.

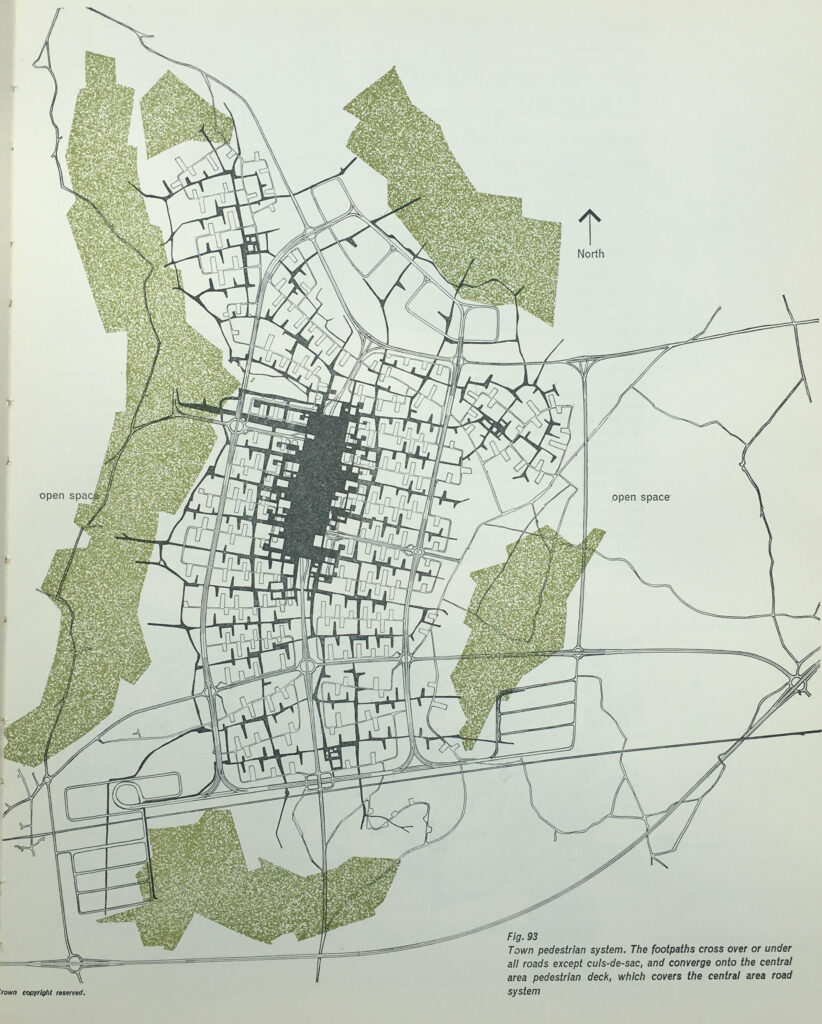

To allow pedestrians to walk freely and safely around the town, a system of pedestrian ways was important, and the following map shows the pedestrian system, with footpaths crossing over or under all roads, and converging on the central pedestrian deck which covers the central area road system.

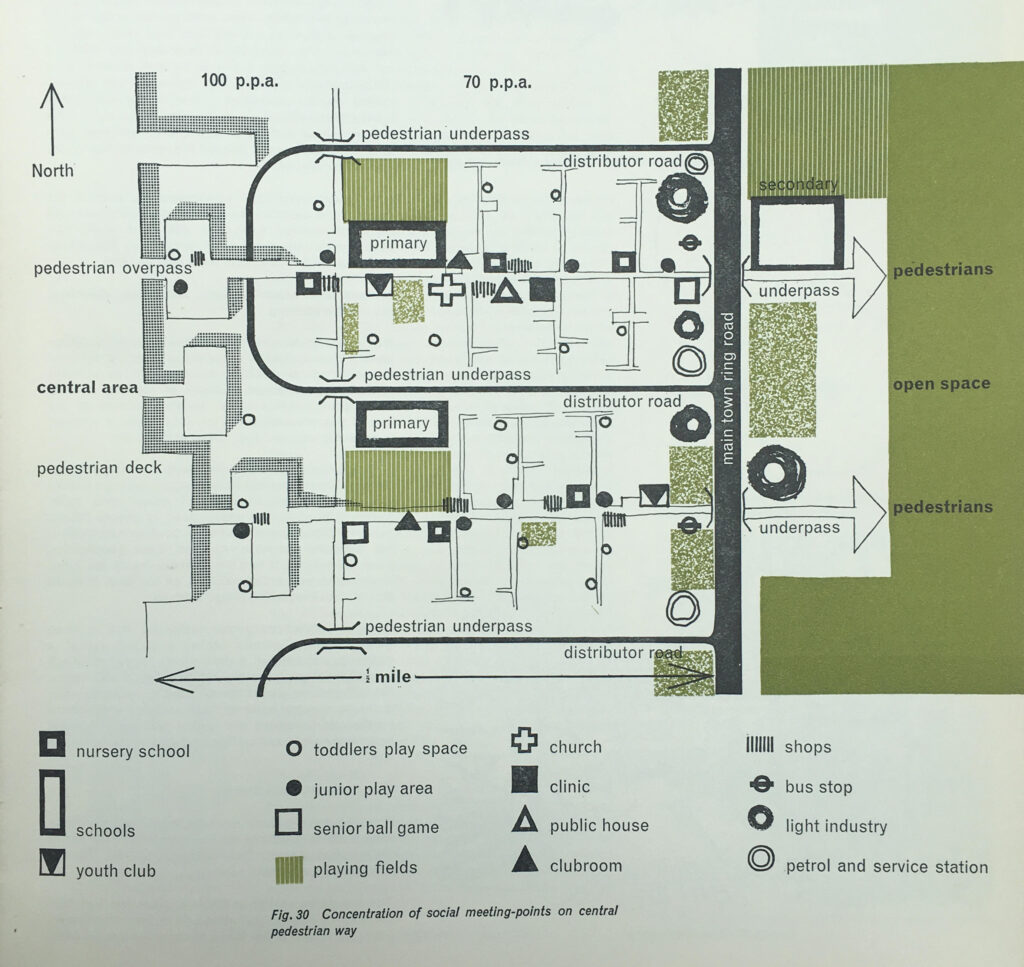

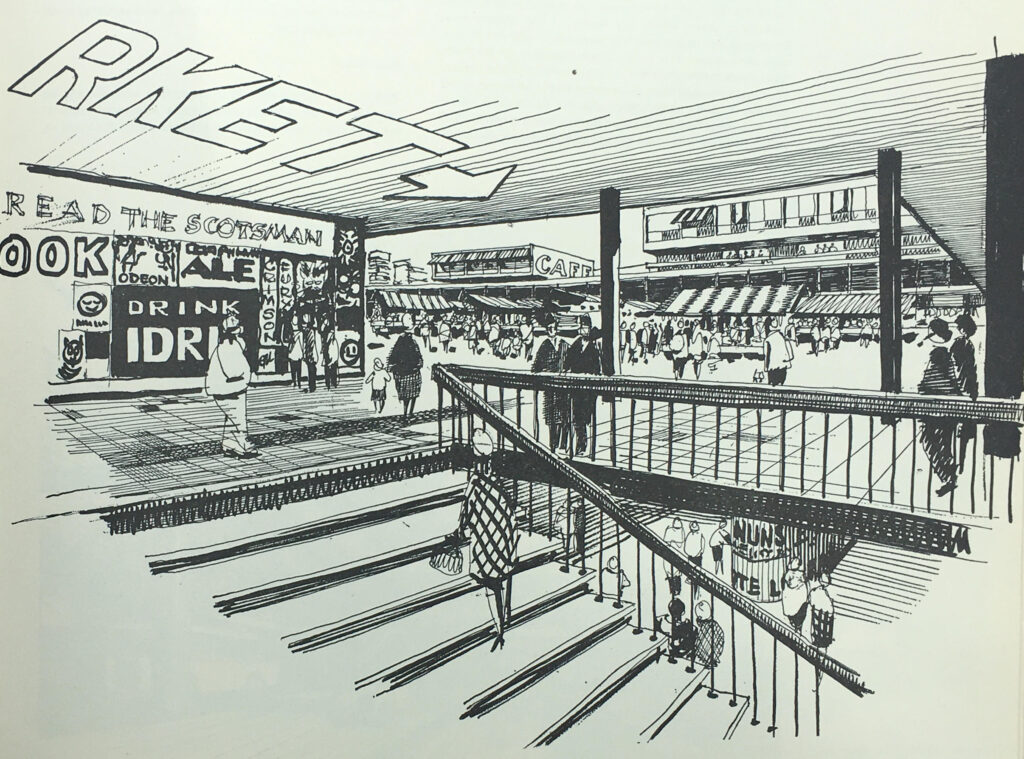

The new town was intended for young families which is illustrated in the design of some of the areas. The following plan shows the concentration of social meeting points on the central pedestrian way, and shows a remarkable number of primary schools, play space and play areas, and a repeated pattern of pubs, churches, clinics, bus stops, light industry and petrol stations, which would replicated in the same pattern across the central pedestrian way.

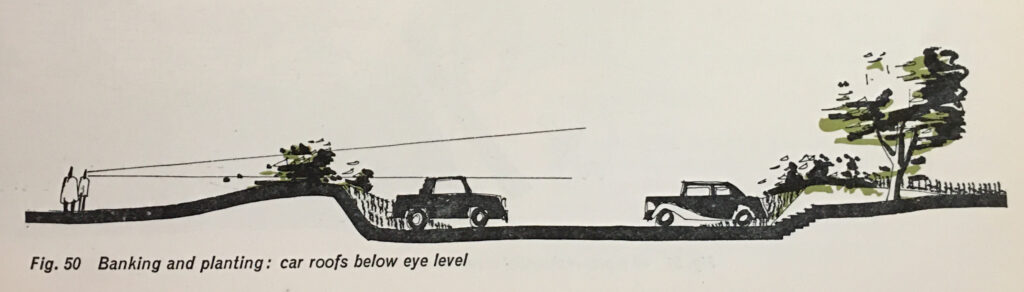

Where car parking was provided within the residential areas, the intention was to try and hide the cars as much as possible, and as the following drawing shows, car parking would be within a lowered area, with banking and planting helping to keep the roofs of cars below eye level:

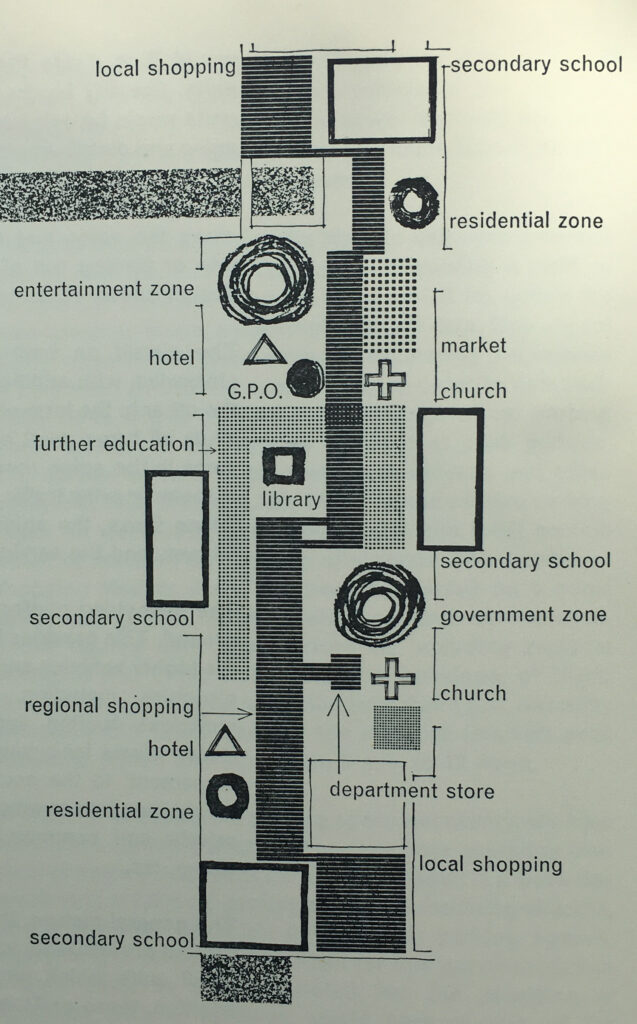

The central pedestrian area was elevated above the traffic and parking areas, and included secondary schools, local shopping, entertainment and government zones, a department store, church, library and post office:

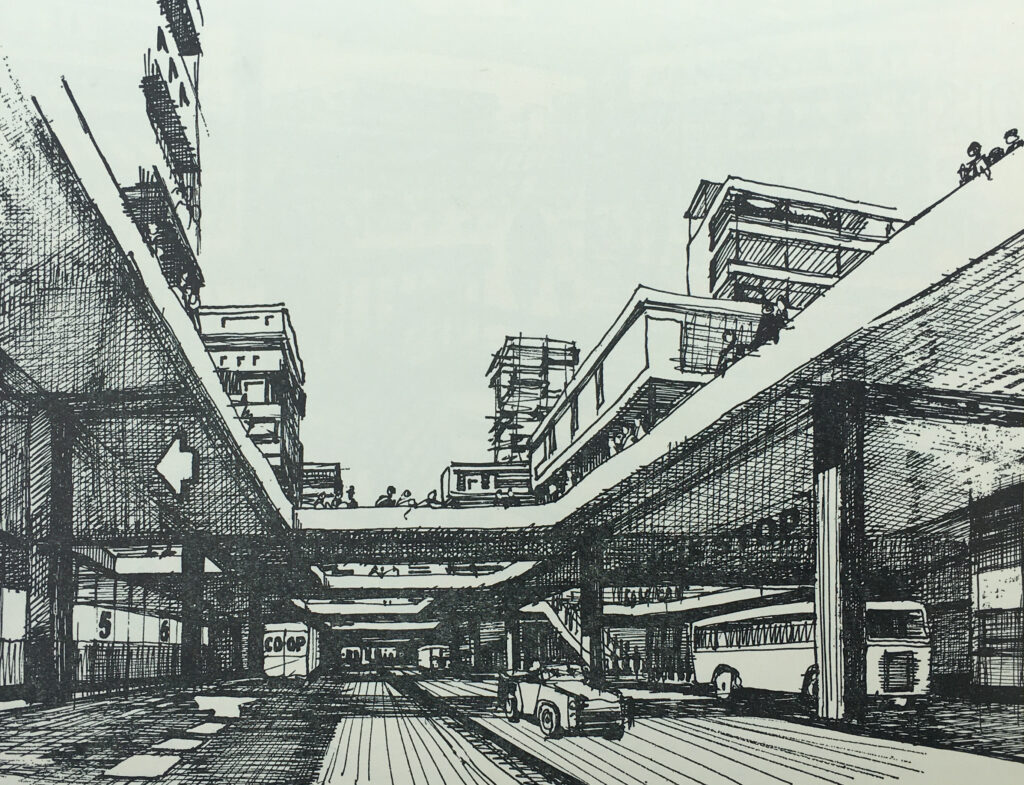

The book has a large number of drawings illustrating what Hook New Town would have looked like. and the following drawing shows the central pedestrian deck as seen from the spine road:

The plans for some of the areas were very forward thinking, but it must be very questionable whether these plans were cost effective, and whether any consideration was given to their ongoing cost and maintenance.

For example, the intention was that the pedestrian deck would be traffic free, however there was a recognition that the businesses and institutions on the pedestrian deck would need servicing with delivery of goods, collection of refuse, how would an ambulance get to the pedestrian deck etc.

The planners ideas included the possible use of electric trolleys to provide transport along the pedestrian deck, and to move goods between the service areas at ground level and the pedestrian deck, hoists could be installed in the communal and service areas and operated by “the local authority or some other central management organisation”.

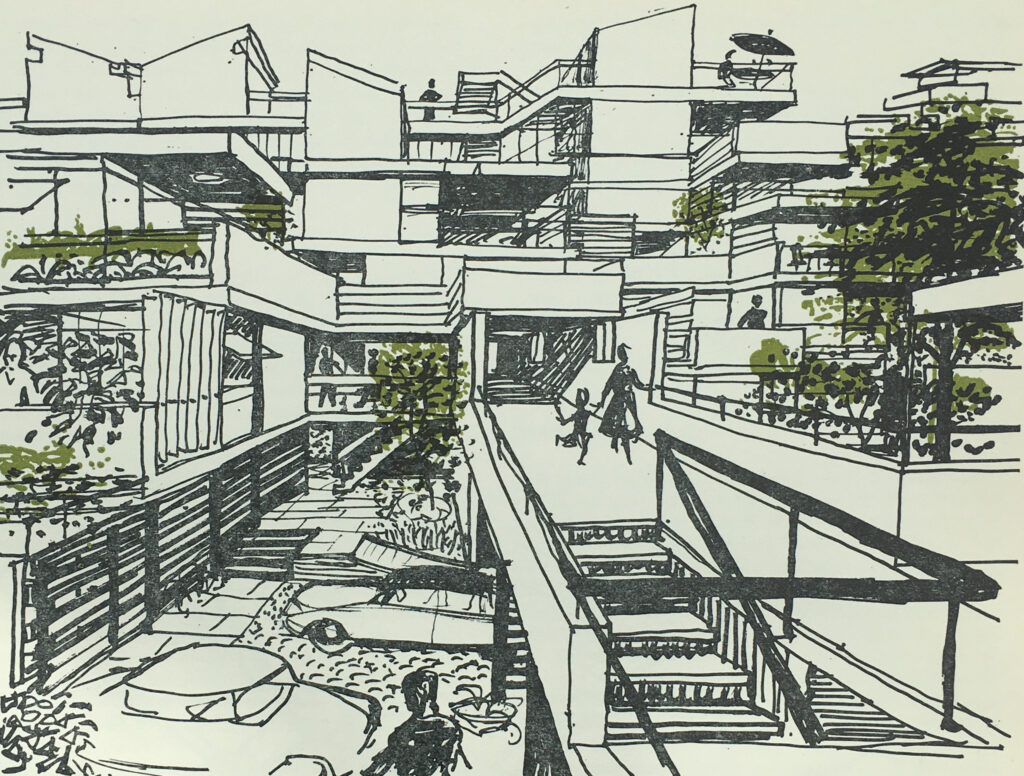

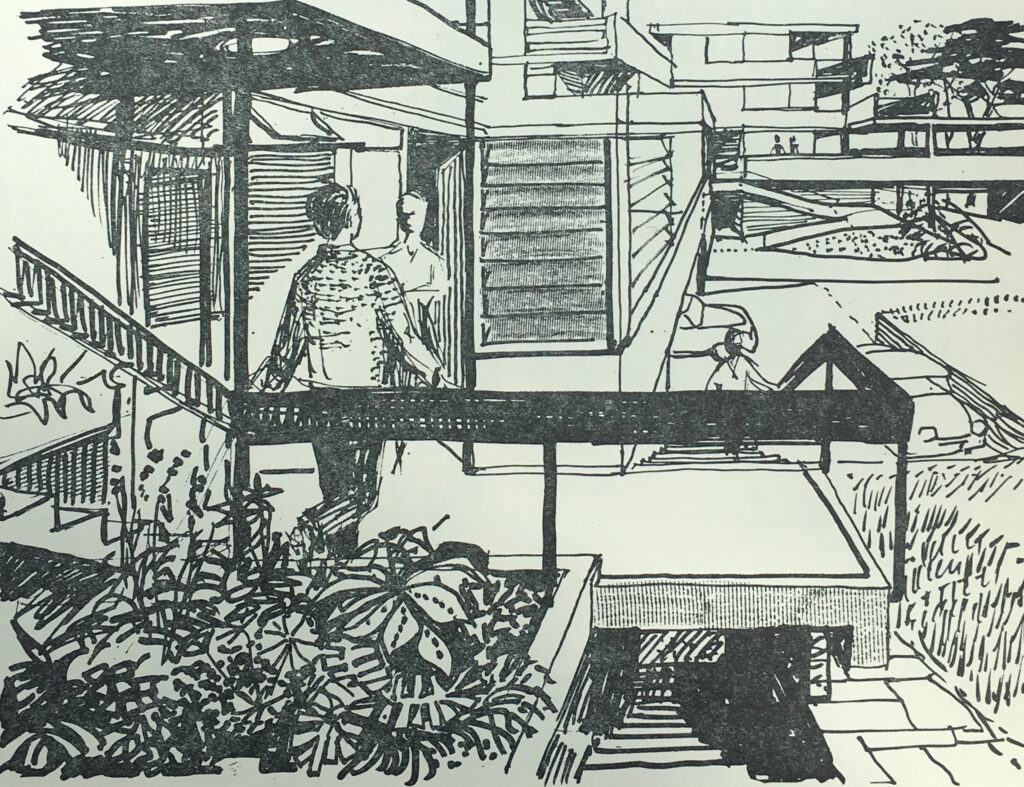

The new town would not have the type of high rise housing that was being built across east London, but would have low rise housing, which would include gardens, off-ground outdoor rooms and pedestrian walkways to separate pedestrians from the streets and parking below:

Upper level gardens and off-ground rooms:

The elevated central pedestrian deck was incredibly ambitious. In the following drawing, the ground level bus stops are shown, with ramps, escalators and lift up to the pedestrian deck:

Once on the deck, there were shopping areas, along with other functions such as the entertainment and government zones, library, and a wide central space which would host a market:

I am not aware of any new town that had such a central pedestrian deck. New towns such as Bracknell and Basildon had central pedestrian areas, with facilities such as shops and council offices, but these were not on fully raised platforms, and transport services such as bus stations would be located at the edge of the pedestrian area.

The book demonstrates the difference in costs for Hook compared to other new towns.

The book identifies the costs for the Hook development of major roads, intersections, distributor roads, bridges, viaducts etc. as £8,707,700, whilst for the same services in an existing new town, the costs would be £3,146,900, so Hook would have cost an additional £5,560,800 – a huge amount which must have been difficult to justify.

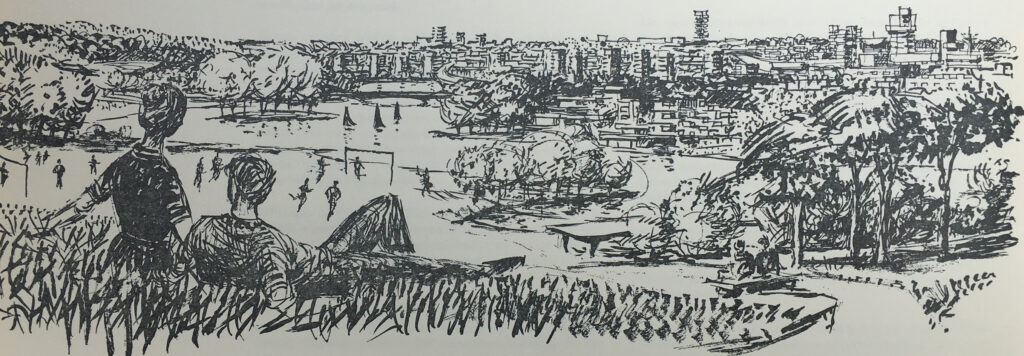

The intention with Hook is that the area immediately surrounding the town would offer opportunities for relaxation, sport, hobbies and access to the countryside.

One drawing shows Lakeside Recreation:

And the following drawing shows “Major open space seen against compact housing”, where a couple are relaxing on a small hill, overlooking a football game, with lake and surrounding trees, and the town across the lake:

The book has lots of data covering population size, age distribution, numbers employed, persons per household and mix of households etc.

Where possible, data from other new towns, or national data was used to model what could be applicable for Hook.

Some of the data provides a snapshot of the country in the late 1950s, and also how much aspects of the country would change in the following decades.

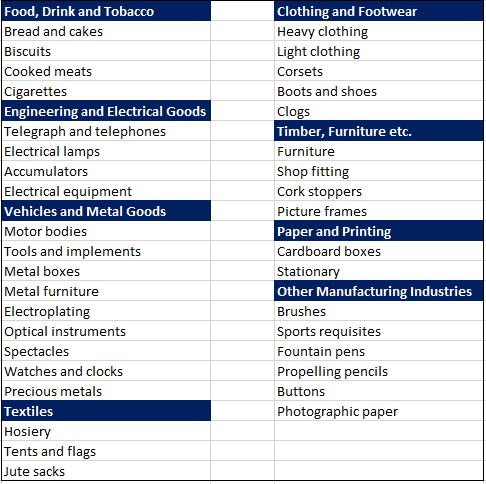

One table covers the manufacturing industries that could be attracted to a new town at Hook, with easy access to the planned M3 and M4. These were:

In the following years, many of these industries would be moving overseas to country’s with cheaper production, others would simply become redundant.

To justify the selection of the above industries as possible candidates to move to Hook New Town, the table includes figures to show how many were currently employed in these industries across the country. For example, there were:

- 9,000 people employed making tents and flags

- 108,000 people employed making hosiery

- 17,000 people making corsets

- 4,000 people making cork stoppers

- 8,000 people making fountain pens and propelling pencils

The proposals also estimated that when the town was fully built and occupied after 50 years, employment would be split 50 / 50 between manufacturing and service industry jobs.

The London County Council’s proposals for a new town during the 1950s were met with delay and a lack of decision making. The Conservative governments during the 1950s were not really supportive of the New Towns movement, as they required state funding and their development was managed through non-elected Development Corporations.

The L.C.C. approach to various Ministers of Housing and Local Government were met with supportive noises, but no real action that would support the L.C.C. proposals.

A decision of sorts was finally made in August 1957 when the L.C.C. proposal was agreed in principle, however there would be no special funding from the exchequer, and the proposal was subject to agricultural considerations and the general economic environment.

On the 22nd of October 1958 a meeting was held in County Hall between representatives of the London County Council and Hampshire County Council, during which the L.C.C. communicated the decision to Hampshire, without the opportunity for any discussion.

After the decision was made public, it was met by a huge amount of resistance from the residents of Hook, local farmers, landowners, civic groups and local councils. Even within London there was opposition, with the London evening papers asking why Londoners would want to move out to Hampshire, and whether the new towns were forcing those living in London to move out to these new developments.

Hampshire County Council refused any cooperation with the London County Council.

The appropriately named London Road, the old A30, the main street running through Hook today:

The historic importance of the road running through Hook can be understood through the Grade II listed White Hart Hotel:

The listing states that the White Hart is “C18, early C19. Old Coaching Inn, with buildings around a yard: the front (Early C19) of 2 storeys in 2 sections”.

The local newspapers of the time were full of objections to the new town. A few articles mentioned that it was the London County Council’s intention to clear much of Wapping and Hoxton and relocate people to Hook.

There were also alternative suggestions as to were a new town should be located with the Aldershot area proposed due to the significant Army landholdings in the area. It was believed that the Army could release a large proportion of this land, however the Army objected.

The following article is from the local paper with a very long title of Reading Mercury Oxford Gazette Newbury Herald and Berks County Paper, on the 8th of November 1958:

“HOOK NEW TOWN PLAN – That Hook New Town would cover eleven square miles, absorb a seventh of Hartley Wintney Rural District and involve an expenditure of about £7 million for land purchase, were estimates given at a special meeting of the Council. The general feeling was that Aldershot and Farnborough were far more suitable areas for such mammoth development.

The Parish Council, although obvioulsy entirely opposed to the new town plan, accepted a warning from Mt. T. Chapman Mortimer to await further information before formally registering opposition.

It was agreed to write to the Rural Council and say that the new town proposal was viewed with considerable alarm and to ask for further information.

Mr. D. Franklin, chairman, said that in Bracknell New Town area the value of properties had fallen sharply. Houses within the town area were razed to allow for new building and roads.

Mr. A.R. Wright thought the site was not far enough from London. It was ludicrous to put a town as big as Aldershot and Farnborough combined in a position where many of the residents would go daily to work in London and so aggravate the traffic problems in the district, and it was criminal to put 60,000 people on the fringe of Britain’s third ranking airport.

Wapping and Hoxton were the areas which the L.C.C. proposed to clear, said Wing Commander L.H. Cooper and he visualised dockers going up daily to their work.

Hartley Wintney shopkeepers are struggling to keep their businesses going, said Mr. Wright, and the new town would have a superb shopping centre with super-markets. It would be like having Knightsbridge on your doorstep, he said. It could mean many Hartley Wintney traders losing their businesses.”

The above article is typical of the many news reports of the time. There appeared to no one in the area who was in favour of Hook New Town.

The Old White Hart, another of the pubs in Hook on what was the A30 through the village:

Throughout the time that the proposal for Hook New Town was being progressed, Hampshire County Council was trying hard to avoid any involvement.

The Aldershot News reported on the 13th of February 1959 that: “Hook new town not abandoned – The Hook new town project has not been abandoned according to an L.C.C. spokesman, who this week told the Aldershot News that the Council’s Housing Committee is giving careful consideration to the position now that Hampshire County Council has said it cannot consider the establishment of a new town anywhere in the county.”

The Evening News reported on progress on the 10th of December 1959, and commented that: “Investigations have been somewhat delayed at the outset by the unwillingness of Hampshire County Council to join them, the committee added, various details will require further consideration.”

The station at Hook:

Hook is on the mainline into Waterloo Station, which was one of the benefits identified by the L.C.C., as well as the two proposed motorways, the future M3 which would run to the south, and the M4 which would run to the north.

The London County Council’s proposals for Hook New Town finally came to an end in 1960. There was much local opposition, and the county council has simply refused to get involved.

There was still pressure for large amounts of housing in the area around London, and Hampshire County Council, came to an agreement where this could be built, as reported in the Hampshire Telegraph and Post on the 17th of May, 1960: “Three Hampshire Towns May Expand – Proposals for the expansion of three towns in North Hampshire to accommodate overspill population in London received overwhelming support from Hampshire County Council at its meeting in Winchester on Monday.

The proposals envisage the development of Basingstoke to take 50,000 overspill population, the expansion of Andover to take 15,000 overspill and Tadley, near the Aldermaston Atomic Research Establishment, to take about 15,000.”

So Hook survived. It would grow in the following decades, but would not see migrations of people from Wapping and Hoxton. Today, the population of Hook is under a tenth of the level that the L.C.C. planned for the new town.

Emphasis shifted to the continued development of Basingstoke. It would be fascinating to know if, and how many, residents of Wapping and Hoxton did relocate to Basingstoke, or any of the other new towns.

New towns had an extraordinary impact on the villages that they took over. To get an impression of this, we can look at Bracknell, a new town that was developed in Berkshire, not that far from Hook.

The proposal for transforming Bracknell came in the immediate post-war planning for new towns, when the existing market town was identified as a new town in 1949. It would develop over the following decades.

Bracknell, as with Hook, was on a railway line into Waterloo, and was between the proposed M3 and M4 motorways.

The population of Bracknell today is around 118,000 so is probably around the size that Hook would have have achieved.

The town was designed following similar principles to Hook, but the central shopping area was not elevated. Housing was developed in community areas, traffic was directed around the central core, there was plenty of parking, new industrial areas were built around the town to encourage local jobs rather than the town acting as a dormitory for London.

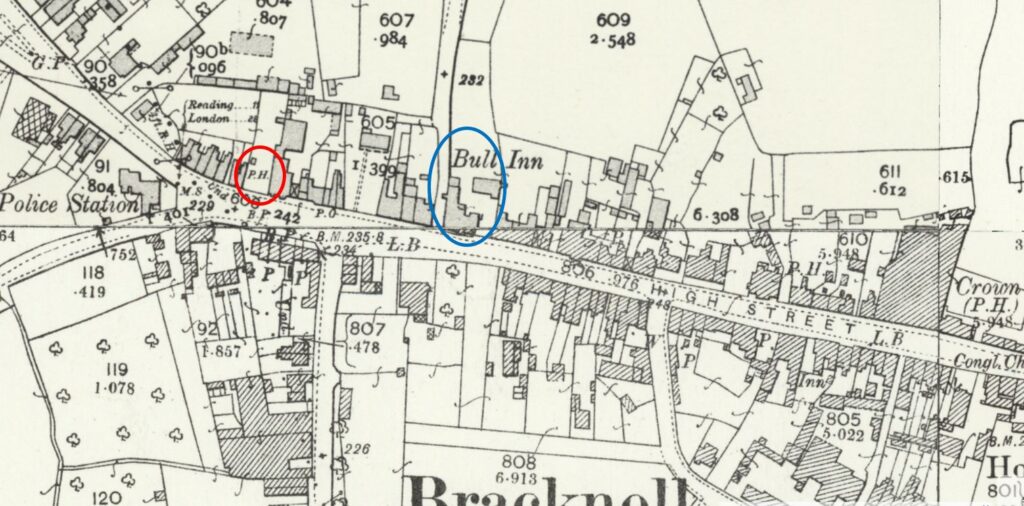

The 1898 Ordnance Survey map shows the central High Street of Bracknell. It had not changed that much by the time it was declared a new town (‘Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland“):

Nearly every building along the High Street in the above map was demolished to make way for a new shopping centre at the core of the new town, and as the news report quoted above from the 8th of November 1958 stated “Mr. D. Franklin, chairman, said that in Bracknell New Town area the value of properties had fallen sharply. Houses within the town area were razed to allow for new building and roads”.

In the above map I have circled in red the PH symbol for a pub, which was preserved during construction of the new town, and we can still see the pub today:

The block of flats behind the pub is recent, and was built on the site of a large office block which had been part of the new town development.

To the left of the entrance into the pub is a milestone that confirms that this was on one of the roads between London and Reading:

The milestone confirms 28 miles to London and 11 to Reading, the same distances as shown in the map above:

Walking along the route of the old High Street, now the pedestrian route into the main shopping centre, we come to the pub marked by the blue circle in the above map. The pub is still to be found, with the same name, but surrounded by a very different scene. This is the Bull:

Original new town design for shops at ground level and flats above:

Another building remaining from the original High Street:

View along what was the High Street, now completely transformed:

One of the problems for new towns is the need for constant reinvention. Bracknell was built with a central shopping centre that by the start of the 21st century was looking rather dated.

The shopping centre was also lacking any local character, and was the same as any other mid 20th century shopping centre. Whereas towns with a traditional High Street can evolve, a large shopping centre cannot easily do this, with large amounts of space dedicated to shops.

To try and address this, the central area of Bracknell recently went through a major redevelopment, with large parts of the original new town development demolished and replaced with a new design,

This is the view looking north from the original High Street, looking through into what were the fields behind the High Street. The view is the recent development. replacing the original new town build.

The proposals for Hook show the influence of London on the counties around the city, and in the 1950s the London County Council considered the area south of a line between the Wash and the Solent as within the pull of London.

That description fits the map, where London sits at the centre, with a system of new and expanded towns circling around the central city, and the new towns we see today, such as Bracknell, show what could have become of the area around Hook.

In 1968 my family moved from Clerkenwell, London to Andover as part of the London overspill. Our housing estate was surrounded by farmland and open fields which are now lost due to the significant housing developments built over the years.

There seems to be no mention of the developers behind these new towns and doesn’t appear private people behind their formation. Planning applications?

Many cities in America resulted from private investment. Venice, California for example originated from one of the Kearney Bros. Tobacco Company owners out of NYC.

Viewed through modern eyes, the complete absence of consultation – with those who might be expected to move out of London, and with the authorities and people in the chosen locality – is striking. It seems the LCC simply expected everyone else to go along with their ideas.

A narrow escape for Hook, clearly. As for “a recognition that the businesses and institutions on the pedestrian deck would need servicing with delivery of goods, collection of refuse, how would an ambulance get to the pedestrian deck etc.”, it would have been done just as it is still done today in the City of London – servicing at ground (road) level with lifts, just as with any ‘normal’ building. And you don’t need an ambulance on the City’s Highwalks because cars won’t be there so you won’t get pile ups etc; thus nothing more than foot access for paramedics etc is needed.

The drawings always suggest a futuristic utopia but with modern eyes you can see how decades of neglect and changing needs would have left Hook looking now.

(Personally I think the people would have noted the multiple spelling mistakes on the table of manufacturing industries and not wanted such people in charge of the future of their town! Of course these may have been a transcription error)

Not to mention the incorrect spelling of Hartley Wintney!

No idea how I missed that – thanks for pointing out. Corrected.

Corrected – thanks for pointing these out. It was late at night when I read through the post.

I grew up in Blackwater just up the A30 from Hook. My parents had bought a new house on a new housing estate in 1967. Many of the new residents of Blackwater and Bracknell had moved from the Ashtead/Hounslow area. I also recall that Basingstoke had many new residents from Tower Hamlets.

Thanks for this fascinating post whichI read with considerable interest, as some people in my remote village in the highlands are currently embroiled in a heated Facebook spat over a proposed caravan site, with similar lack of consultation with inhabitants, and the arguments for and against are mirrored on a much larger scale in the story of Hook – ie – attract young families, increase tourism – versus noise, light pollution and lack of people willing to work in the service industries needed to support more tourist development.

Thank you for a very interesting article. I was raised in Hoxton in the 1950’s and have never heard of this proposal to move us to Hampshire. I’m sure that at the time my parents would have welcomed a move to a new home ‘in the country’. One only has to look at that concrete monstrosity called Crawley to realize that we had a lucky escape. Unfortunately, the character of Hoxton has been lost anyway due to the imposition of characterless modern housing.

It’s interesting, and I suppose typical for the time, that the proposed town centre was sited some distance from the railway station. I presume this was done on purpose. Trains really weren’t that important in the 1950s, were they?

Really interesting, thank-you. I can only echo what some of the other commentators have said and feel it would have been a brutalist neglected slum by now. I can see from your recent photos that it hasn’t avoided a few ugly developments in recent years.

I got married in 1972. My husband got a job in Enfield where we lived that was going to move to Sandy in Bedfordshire As a newly married couple it was our chance to have a brand new house as at the time gazumping was rife in London and as fast as we saved up we got gazumped every time. The house prices in Sandy were so much cheaper too if we had been lucky enough to buy one, but we got a newly built 3 bedroom house with a garden as part of the new town scheme, We were there until my husbands death in 2015 (43 yrs) and very happy times we had too where our boys were born and educated. We had been on the engaged couples list to start with and about 2 weeks after we got confirmation of our house in Sandy we had the offer of choice of 2 locations in east london for a high rise flat! High rise flat against new house with garden? no contest.

Wonderful stuff. As has been mentioned, if I had had anything to do with it, the developer who wrote ‘stationary’ for ‘stationery’ would have been in the village stocks; end of proposal.

Just remembered from when I worked at HSBC in Lower Thames St. a developer’s proposal for a ‘condo village’ with an ‘Archers’ theme; a huge model complete with Woolsack pub, etc. I kid you not, it was called ‘Forever Ambridge’. Didn’t get the finance, thankfully.

I left Basingstoke in the mid-60s when it was in the early stage of development. I haven’t returned since not wanting to find the old market town I remember gone for ever.

And it grows still. Basingstoke has crumbling infrastructure, the same one hospital of the 60s, less leisure that the 60’s, flogged off the football ground and is with 1/2 fields (that’s if not already joined up to some villages and hamlets) to linking to Oakley, Sherbourne St John, Dummer, Old Basing ….). Developer boxes springing up with appalling construction standards, issues with water and sewage supplies locally, woods built on, parks given over to homes, even verges in front of homes covered over! Hook is now squeezed by new developments, building more housing as I type, there’s a huge superstore in walking distance of the old high street now and many of the industries in both Basingstoke and Hook long gone. Even the Basingstoke I moved to 25 years ago is very different to the one now. Development is about money, not about community and without a car to access work in Basingstoke and Hook, which is essential to travel to workplaces that pay sufficient to earn the money to pay for the places locally, you have no hope!

That was fascinating, thank you. I catch the train from Hook Station most days and live not far away. I am quite glad not to have a decaying, brutalist monstrosity on the doorstep! I must now track down a copy of that book.

I notice that the developers’ drawings always have people walking happily up and down long flights of

stairs -to get to Corbusier’s “streets in the sky”. None of them ever feature women pushing prams or anyone using a wheelchair. It was, of course the era of architects’ love of stairs, stairs and more stairs – since abandoned, but remembered by me whenever I visit the Barbican and have no option but to use the outside flights of poorly designed steep steps of crumbling tiles.

Another fine article and one which I could add a great deal to.

The Hook proposals were partially built, not in Hampshire but in South East London.

I’ve studied Hook and the second attempt at building it for more decades than I’d like to remember. But, there’s quite a lot to say and a reasonably informative reply might give the impression that I’m trying to hijack A London Inheritance!

The matter concerns the later history of the Royal Arsenal and the industrial historian who contributes here, Dr Mary Mills would confirm my credentials.

I’ll await our author’s permission and he is most welcome to decline and delete this comment.

Another very interesting piece — thank you. Content as ever is excellent but you do need an editor!

Hook has not escaped becoming a new town it just had a era of reprieve, avoided the concrete walkways and grey block developments, which allowed the old to remain, albeit now being challenged by development, not to make lives better, but to increase developer’s profits and fill council revenue pots imo. Hook still has the old village high street, but is now being squeezed by a huge number of new build developer profit box developments within minutes of the high street, a giant superstore within walking distance of the high street and a lack of workplaces, as even the business parks on the edge of Hook struggle to remain occupied, so live in Hook and have to commute to work. Basingstoke which got the new town, has lost woods, parks and open ground and is within 1/2 agricultural fields of joining to some of the surrounding villages (Old Basing, Oakley, Sherbourne St John to name a few), but little of the large industries of the 60s to 00’s remain and it has increasingly becoming a dormitory town with a very old infrastructure, which seems to have been neglected since the 60s in many places – a huge town with a crumbling hospital, little if any leisure and even flogging off the football ground to the highest bidder! We even have a projected huge new development of Manydown, a town in its own right about to appear if the council can ever get its act together. 50s and 60s plans showed hope; what they should have hoped for is care for those that live, work and need to thrive in the towns, which increasingly seems to be at the end of any thinking. They certainly didn’t factor in that the train is not the link it should be, but the car is key to thriving where homes are built to fit the space and the car is needed to access work to pay for that place!

Two words came into my mind as I read this splendid article :-

“Milton Keynes”.

Probably the largest of all of the new towns ?

Fascinating article. Born and grew up in Basingstoke in the 70’s. My parents had moved from London to Basingstoke in their early 20’s with the promise of work and a brand new council house. Followed in fairly quick succession by virtually the whole extended family. All living on the same Estate.