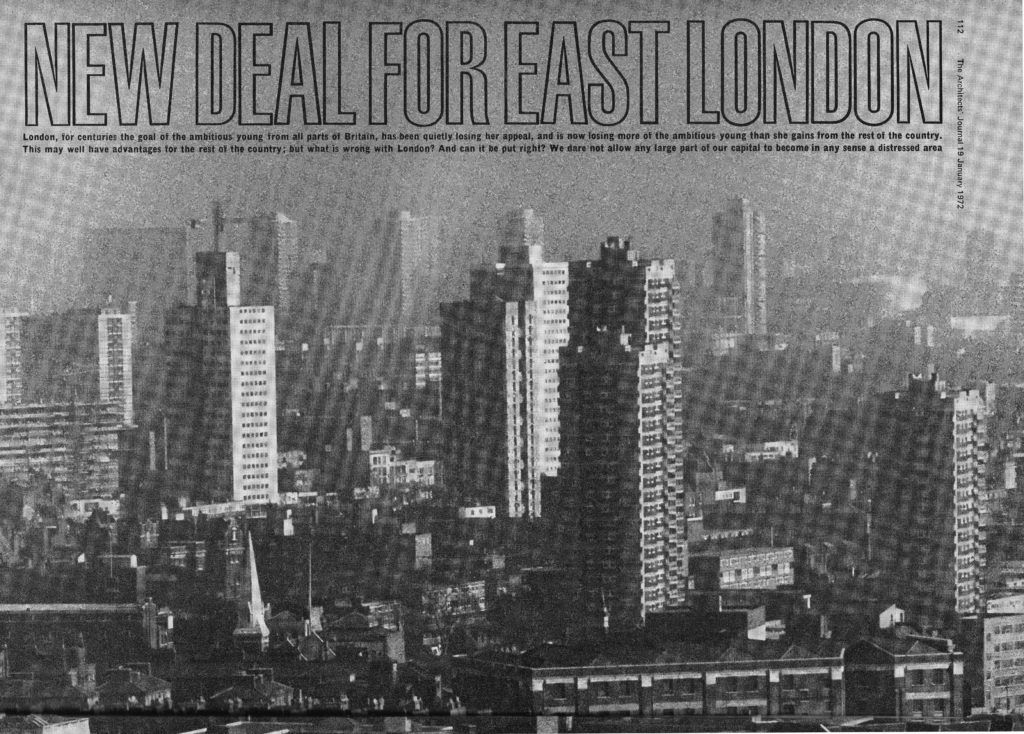

Before continuing on from last week’s post, it is interesting to understand why so much of East London had reached the state described by the Architects’ Journal in 1972. Such changes do not usually just happen, there is some underlying influence at work to cause so much gradual dereliction over such a large area.

The following extract titled “Planned Depression” from the 1972 article goes someway to describing how this had come about:

“Perhaps the most cheering factor in the situation is that it has now been recognised by Greater London’s planners that the economic depression existing throughout east London is the result not of thoughtless neglect, but of national planning policy. This was explained convincingly by Dr. David Eversley, now chief strategic planner to the GLC, when he spoke to the conference of municipal treasurers last year. As that important speech was not widely publicised (municipal treasurers not being regarded as newsworthy by the national press), this seems a good opportunity to present his argument in some detail.

First perhaps, one may recall that, whereas in the ‘hungry 30s’ when Ramsey MacDonald was prime minister of a national government, everybody burst into despairing laughter when he promised that progress was going ‘on and on and on, and up and up and up’, since 1945 this has in fact been the assumption of most of our economic advisers – at least until recently.

Founded on that assumption, it was a major goal of post-war planning policy to prevent London from going on and on and on (though it has certainly gone up and up and up) by inducing people to leave the capital and go to new towns. This was done by bribing industry, to establish itself in these towns by the system of industrial development certificates accompanied by various financial encouragements to leave overcrowded London, and other over-developed industrial centres and go to the new towns. As Dr. Eversley pointed out, the characteristic of the British approach has been for at least 30 years, ever since the intra-urban approach to the city’s problems concentrates largely on large-scale redevelopments; slum clearance followed normally by high-density, high-rise rebuilding; above all ambitious city centre schemes, designed to preserve the local and regional dominance of the older centres at a time of changing settlement habits….and into the age of private motor transport.

The distinguishing characteristic of British planning for urban problems in the last two decades, Dr. Eversley pointed out, has been that compared with most other countries, it has been extraordinarily successful… that the stated aims of national planning have by and large been implemented. Cities have held on to their Green Belts, the seven conurbations all had lower populations and London will by 1981 have fewer than 7,000,000 inhabitants – that is, about 2.5 million less than there would have been but for planned and voluntary out-migration.”

Although there was rebuilding across East London (but much of the high-density and high-rise housing as mentioned by Dr. Eversley), the inducements for both industry and people to move out to the new towns, (with the Essex new towns of Harlow and Basildon being the new homes for significant numbers of east Londoners), contributed to a lack of employment opportunities and a reducing population across east London.

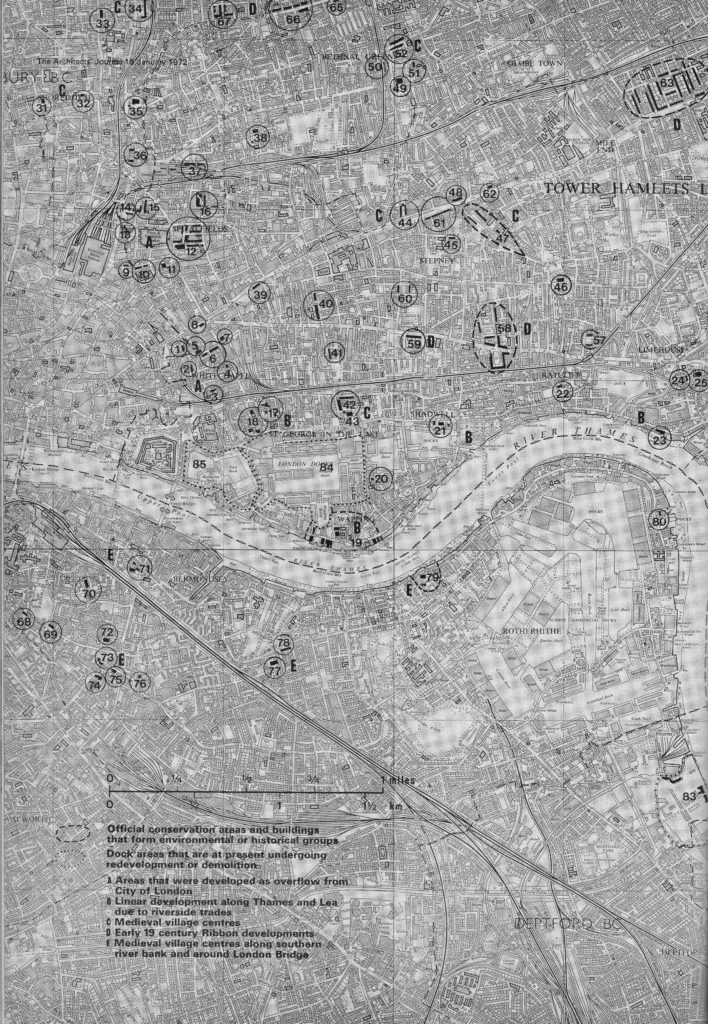

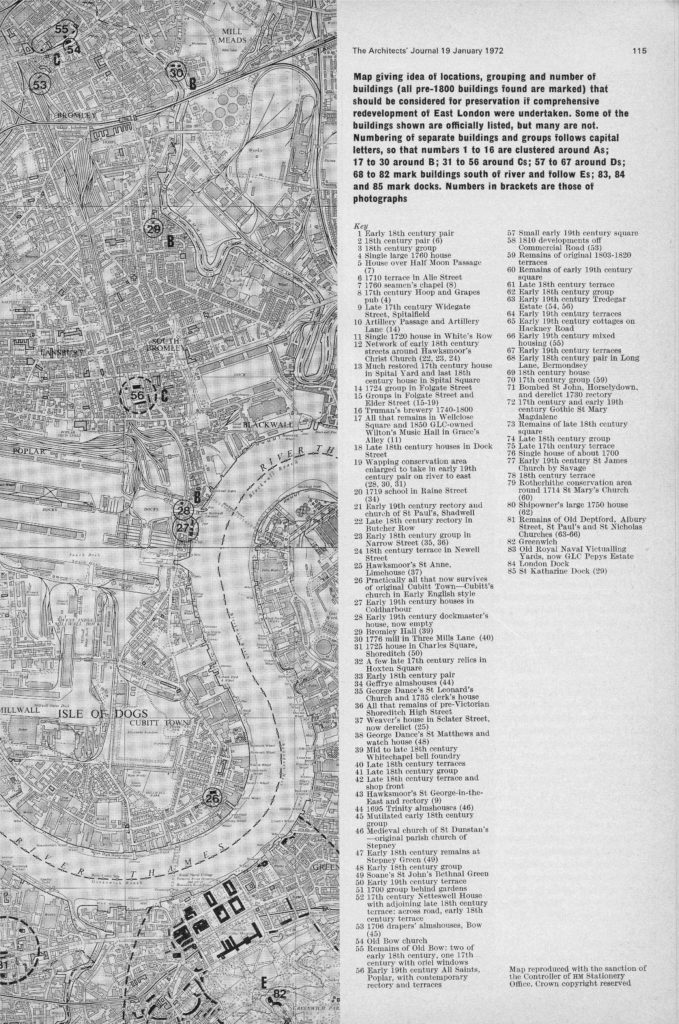

Following last week’s walk around Whitechapel, my next stop following the Architects’ Journal 1972 map is Spitalfields. The last of the category A sites on the map which the Architects’ Journal classified as “Areas that were developed as overflow from the City of London”.

I must admit to feeling somewhat nervous in writing about this area of London which continues to be described in such detail by the excellent Spitalfields Life blog and in the books by Dan Cruickshank who was so instrumental in the years following the Architects’ Journal report in saving so much of this area. (Dan Cruikshank’s latest book “Spitalfields: Two Thousand Years of English History in One Neighbourhood” is sitting on my shelves waiting to be read)

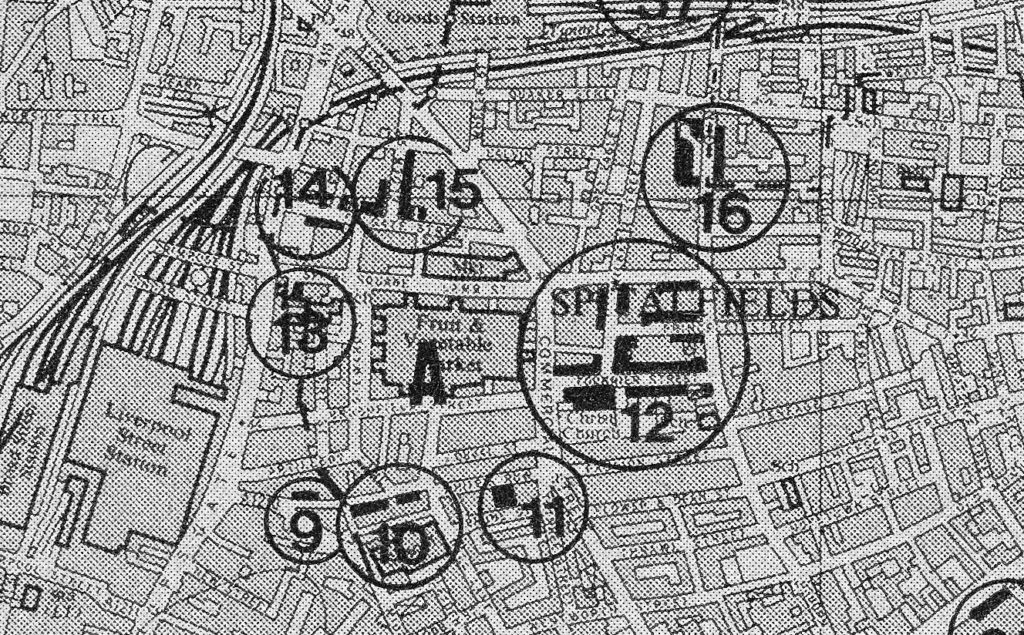

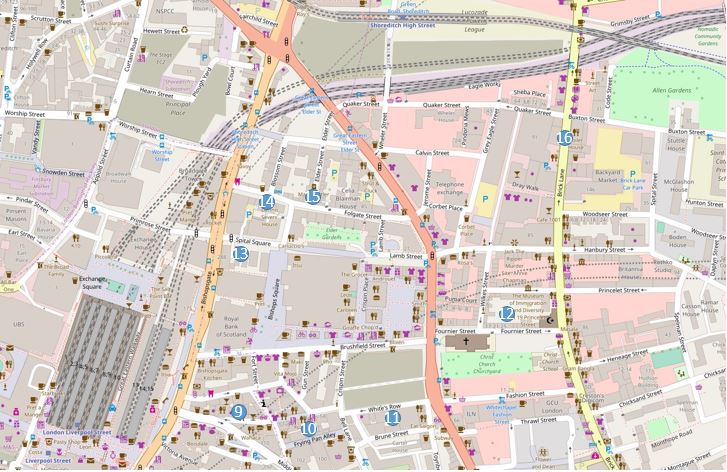

The following map is an extract from the large map in the 1972 Architects’ Journal covering the eight locations around Spitalfields.

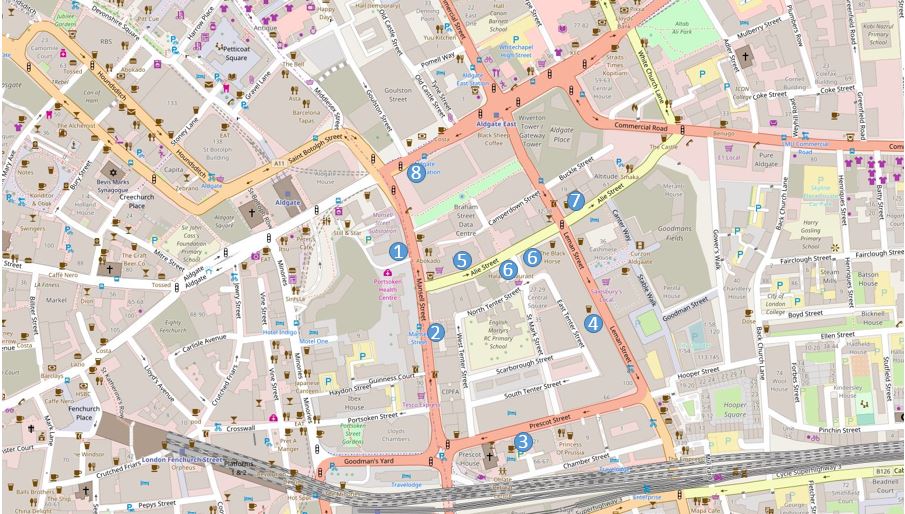

I have marked the locations on the following extract from OpenStreetMap to show the area as it is today. Comparison of the maps show the loss of Broadstreet Station, adjacent to Liverpool Street Station in the lower left corner. The Goods Yard at the top centre of the map, and the market in the middle of the map when it still the original fruit and vegetable market in 1972.

The first stop is site 9 on the above two maps. To follow the locations numerically, Widegate Street is reached by turning off Bishopsgate into Middlesex Street where a short distance along we reach the turn into:

Site 9 – Late 17th Century Widegate Street

On walking into Widegate Street we enter a series of narrow streets that retain their original layout and give a glimpse of what this part of London would have looked like from the time they were built until post war development.

As you walk down Widegate Street, the buildings on one side are recent all the way down to the building just before the Kings Stores pub with the buildings on the opposite side being a mix but appear to be mainly from the 19th century.

The following view is from the junction of Widegate Street (on the left) Sandy’s Row (on the right) and Artillery Passage. The corner building displays a construction date of 1895.

Looking down Widegate Street from the Middlesex Street end. Most of the buildings appear of 19th century vintage. The Architects’ Journal title for this location is “Late 17th century Widegate Street” and the black location mark on the map is on the left side of the street near the junction with Middlesex Street which may refer to the white-painted building on the left. This is a different style to the rest of the street and therefore may be a late 17th century building, but I would not apply this description to the whole of Widegate Street.

I assume that the buildings that once lined the opposite side of Widegate Street were of similar style to those that remain on the left.

The next stop is at the end of Widegate Street where we enter Artillery Passage.

Site 10 – Artillery Passage and Artillery Lane

Artillery Passage is a narrow foot passage that leads down from Widegate Street to a curve in Artillery Lane.

In the photo below I am standing in Artillery Lane looking down Artillery Passage. Just behind me are numbers 56 and 58 Artillery Lane which are from around 1720, with replacement Georgian facades from the 1750s. Number 56 retains its Georgian shop front.

When I was taking these photos there were two large white lorries parked in front of these buildings. I returned later and another set of large delivery vans were parked immediately in front. This corner of Artillery Lane seems to be the parking place of choice for lorries making their deliveries to the shops and restaurants here, and in Artillery Passage. I shall have to return on a Sunday when hopefully the area is free of deliveries.

Despite trying to read the faded sign on the first floor of the corner building from many different angles, I could not decode the faded lettering. I have found sites on the internet that state it reads “Fresh Milk Daily from The Shed”. Perhaps it would be clearer in better lighting than on a December day.

In the photo above, Artillery Lane is the road curving round to the right where it heads to Bishopsgate. Today, Artillery Lane continues behind where I was standing up to the junction with Crispin Street and Bell Lane. Up until 1895, this short stretch of road was known as Raven Row. Just to the northeast of this point was the five acres of land that until the end of the 17th century was used for longbow, crossbow and gun practice and was known as the Old Artillery Ground. Interesting to speculate whether Ravens also frequented this open area and gave this short street the name Raven Row.

Artillery Passage remains a narrow passage between what appear to be mainly 18th century buildings. It gives a good idea of what this small area of London would have looked like, despite the shops and restaurants now being rather upmarket.

Coming out of Artillery Lane turn right then immediately left into the next location.

Site 11 – Single 1720 house in White’s Row

White’s Row is a narrow lane running from Artillery Lane to Commercial Street. The Architects’ Journal map has location 11 roughly half way along White’s Row and described as a single 1720 house.

White’s Row is narrow, made worse at the moment as part of the pavement on one side is boarded off due to the large building site between White’s Row and Brushfield Street, meaning that as you walk towards Commercial Street there is nothing on the left. Most of White’s Row one remaining side appears to be either 19th or 20th century. There is one building in roughly the position shown on the Architects; Journal map that answers the description of a single house, however I have some problems with confirming this as a 1720 house.

My photo of the building is shown below. Whilst there are some elements of 18th century design, the building just looks too new. The window casements are also flush with the brickwork. Buildings of the period typically had recessed casements.

My assumption is that design elements of the original 1720 house have been retained, however the majority of this building must be of recent construction.

Leaving White’s Row, I walked up Commercial Street towards Christ Church and this is the view on the left of Commercial Street. The rear of the facade of the old Fruit and Wool Exchange building in Brushfield Street are all that remain, whilst a completely new building rises to the rear of the facade.

To the right of the above photo is the Fruit and Vegetable Market building, with the frontage onto Commercial Street shown in the photo below. The low winter light bringing out the colour of the brick walls – one of my favourite building materials.

Site 12 – Network of early 18th century streets around Hawksmoor’s Christ Church

Site 12 in the Architects’ Journal map covers the network of streets north of Hawksmoor’s magnificent Christ Church including Fournier Street, Princelet Street, Hanbury Street and Wilkes Street.

The first building on the right in Fournier Street is Hawksmoor’s 1726 Rectory. This is a very substantial building, emphasised by the windows being set back a full 9 inches from the facade of the building. The 1709 Building Act required windows to be set back by 4 inches, but Hawksmoor went back a further 5, perhaps to show the depth of the walls.

Opposite the Rectory, Fournier Street is lined with 18th century houses. Note also the deeply recessed sash windows. The 1709 Build Act justified this on the basis that is would be harder for fire to propagate along a street if wooden window frames were recessed and not flush with the facade. It also set the style for how sash windows would develop. A later 1774 Building Act took this further by requiring the sash box (the wooden part of the window surrounding the glass framed panels) also to be recessed into the fabric of the building to reduce further the exposure to fire.

Here is 33A Fournier Street. The boarded up entrance between the two doors is the entrance to a yard behind these houses.

I can find no record of S. Schwartz or the age of the sign, however there are photos from the 1950s showing this as the entrance to the Express Dairy including the following from the Collage collection:

The Architects’ Journal details some of the challenges facing the restoration of Fournier Street: “Built in the 1720s it was one of the most fashionable and solidly constructed streets in the area and shows the obvious mark of the Huguenots. They established Spitalfields’ silk weaving industry and in their houses, to brighten their workrooms, they built large attic windows. The GLC is adamant that this street should be preserved, yet so far has done little to maintain it. Tower Hamlets will pay no money for restoration as the houses, due to their wooden construction, could be inhabited only as single units (quarter-inch wainscot partitions do not correspond to fire precautions and noise insulation specified for flats). If they cannot be restored to council flats, they can be saved only by individuals restoring them to their original purpose as private houses. Any rehabilitation of these houses would demand much greater social change than was necessary in other areas.”

View looking down Fournier Street.

Corner of Fournier Street and Brick Lane.

Leaving Fournier Street, I walked a short distance along Brick Lane, and although Brick Lane is not included in the list of sites in the Architects’ Journal, there are many fascinating buildings, including the following building which was the Laurel Tree pub, built in 1901. The name of the pub is on the middle plaque, the year on the right, and on the left plaque are the initials THB for Truman Hanbury Buxton. A very similar set of decorations can be found on the old Three Suns pub on Wapping Wall (see my post here). Perhaps a project to track the remaining pub buildings that have this type of decoration could go on my list?

Along Brick Lane we now come to Wilkes Street, the next street marked within site 12 of the Architects’ Journal map. The junction of Wilkes Street and Hanbury Street.

Much of the area I am walking across for site 12 was land originally owned by two lawyers from Lincoln’s Inn, a Mr Charles Wood and a Mr Simon Michell. A large area of land between Commercial Street and Brick Lane was purchased by the pair around 1717 and the streets were laid out between 1718 and 1728.

Difficult to see in the following photo due to the deep shadow. The terrace of identical houses running to the left of the modern building on the right were built by the speculative builder Marmaduke Smith in 1723.

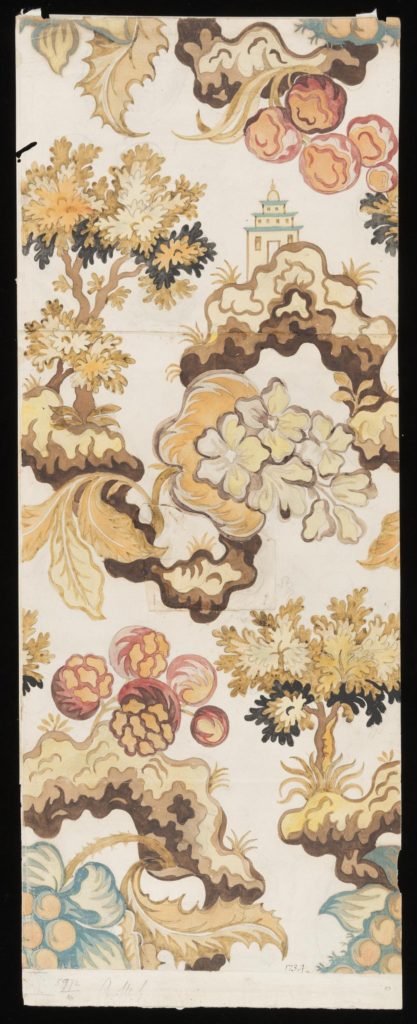

Half way along Wilkes Street is the junction with Princelet Street. The Blue Plaque on the left is to Anna Maria Garthwaite (born in 1688 and died in 1763). Anna Maria was a designer of Spitalfields silks and lived and worked in this building on the corner of Princelet Street.

Anna Maria was originally from Lincolnshire but moved to Spitalfields to be with her widowed sister. She became a celebrated designer of fashionable silk fabrics and specialised in botanical designs. Many of her original designs are now held in the Victoria and Albert Museum.

The following (© Victoria and Albert Museum, London) is an example of one of Anna Maria Garthwaite’s designs from when she was living and working in the house on the corner of Princelet Street.

Houses in Princelet Street.

With interesting window decoration.

As well as recessed windows, the photo above also shows one of the other identifying features for the age of Georgian building – the narrow mortar course between the bricks.

House in Princelet Street showing signage from the previous use of many of the buildings in this area.

The final street within site 12 is Hanbury Street with buildings marked on the southern edge of the street at the junction with Brick Lane:

Fortunately there are many buildings that have survived in the area covered by site 12 and the above photos are just a sample. Many houses were not so lucky to have survived and the Architects’ Journal records how developers worked around the risks of preservation orders in Folgate Street along which we will be walking to reach the next site:

“Around the corner, two houses in Folgate Street and most houses on the unrestored Elder Street are owned by a private developer. On the site in Folgate Street he wants to build offices, which the GLC oppose.

The day before a preservation order was to have been served on them, one was gutted by fire, and one Sunday soon after, they were demolished. There is a feeling that he will not restore his side of Elder Street to residential use, unless he is given permission to build offices on the now vacant site in Folgate Street.”

Site 13 – Much restored 17th century house in Spital Yard and the last 18th century house in Spital Square

To reach site 13, I left Hanbury Street, crossed over Commercial Street, walked down Folgate Street then turned into Spital Square.

The map locates the house almost adjacent to the entrance to Spital Yard and if I have located the correct building it is the one on the right in the photo below.

The above photo also demonstrates the impact that the ever growing glass and steel office blocks that are surrounding these 18th century streets in Spitalfields have on the views of the buildings.

Just along from the above buildings is the entrance to Spital Yard.

The house at the end of the yard fits the description of being “much restored” and the blue sign reads “In this house, Susanna Annesley mother of John Wesley was born January 20th 1669” which also fits with the 17th century description, although I am also fascinated by the adjacent building which is the head office of the Architectural Heritage Fund as this also looks to be of some age.

Site 14 – 1724 group in Folgate Street

Folgate Street between Bishopsgate and Commercial Street has a fine mix of buildings. The 1724 group are marked on the map as nearer the Bishopsgate end of the street and I believe are the houses shown in the photos below.

Including the wonderful Dennis Severs’ House, with the doorway dressed for Christmas as I walked passed in December.

Site 15 – Groups in Folgate Street and Elder Street

Elder Street can be found roughly half way down Folgate Street.

In the Architects’ Journal it is described in 1972 as “depopulated and isolated between the market area and a busy main road”. In the extract above about the fire at the house in Folgate Street there is the implied threat by the developer that he would not restore his side of Elder Street. Elder Street was in a bad way in 1972, however today the street is lined by restored buildings.

When restored the developer was selling the houses in Elder Street for £20,000 apparently with no lack of buyers. I could not find any houses for sale in Elder Street today, but estate agent estimates value houses at between £1.5 and £2.5 million – a considerable return on £20,000 in 45 years.

The mix of different styles and architectural features indicates the individual construction of each of these buildings rather than an identical terrace which can be found in a number of other streets such as Wilkes Street.

Note the building on the left with the bricked windows in the photo below. These are dummy window features added to break up what would have been a continuous slab of brick. The internal layout of the houses does not allow a window at these locations, as can be clearly seen on the first floor with the window across the two doors on both sides of the two houses.

Site 16 – Truman’s Brewery, 1740 – 1800

The final location in the group across Spitalfields is the Truman’s Brewery complex which can be found along Brick Lane.

Whilst the Architects’ Journal identified Truman’s buildings as worth preserving, they also identified the brewery company as a potential threat “It is not just small private developers exploiting this environment for personal gain – big businesses are expanding – Truman’s Brewery removed one side of early 18th century Hanbury Street and replaced it with a brick wall. The houses were in need of restoration, but no cosmetics could make a brick wall do anything but detract from a community.”

Reaching site 16 completes my walk around the category A sites in the Architects’ Journal map from 1972. It is good to see how many of the buildings of Spitalfields have survived since 1972, however as the article in 1972 predicted with comments about how Fournier Street could be restored, whilst the majority of the buildings have survived the area is socially completely different.

I have only just scratched the surface of these two areas, Whitechapel and Spitalfields, and I look forward to exploring them in more detail in the future.

In the coming months I will work on category B from the Architects’ Journal – Linear development along the Thames and Lea rivers due to riverside trades.