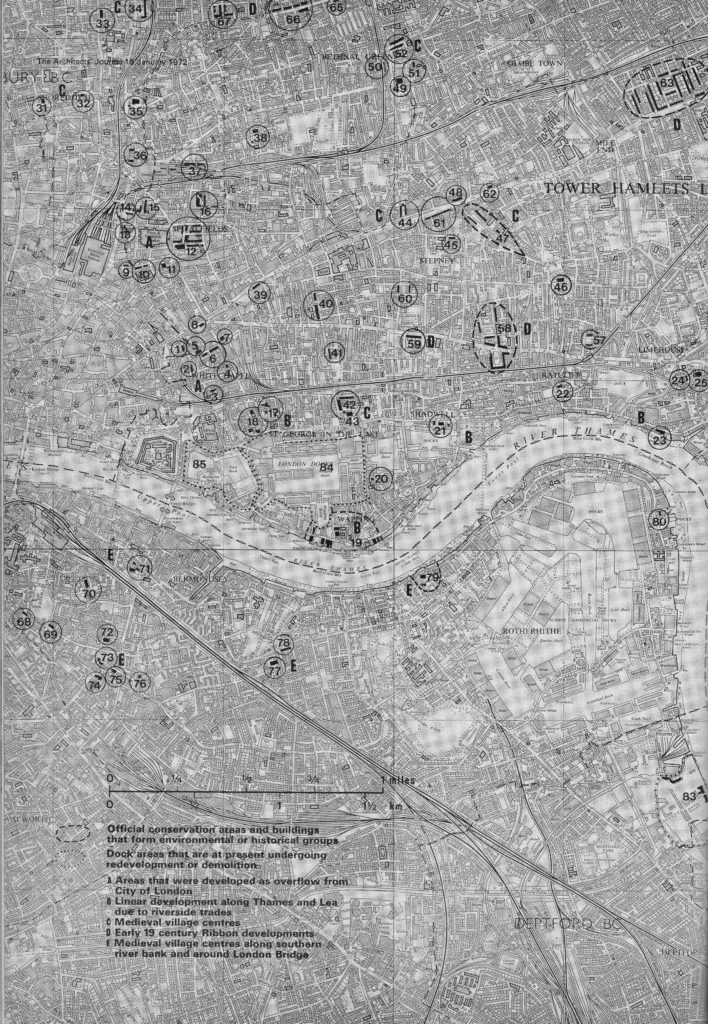

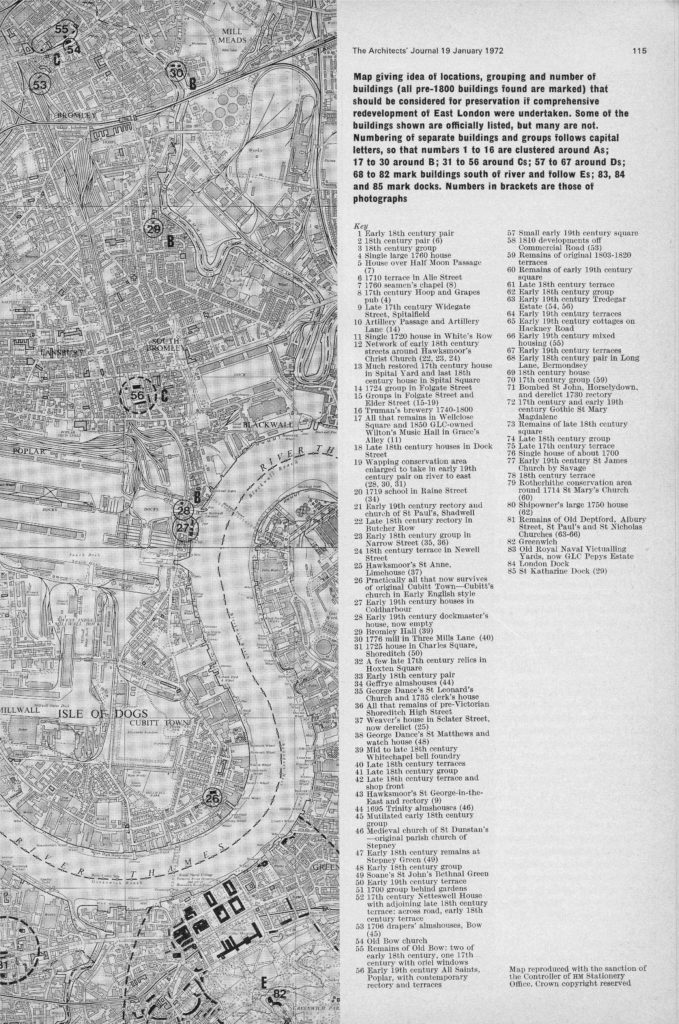

A couple of weeks ago I started exploring East London using the map published in the Architects’ Journal from the 19th January 1972. The map was part of a feature article titled “New Deal for East London” and covered the considerable changes expected to take place across East London and the fate of a number of sites that the Architects’ Journal considered essential for preservation.

Sites across the map were categorised by how they were part of East London’s development. In the past two posts I covered Category A – Areas that were developed as overflow from the City of London.

In today’s post I start on Category B – Linear development along the Rivers Thames and Lea due to riverside trades.

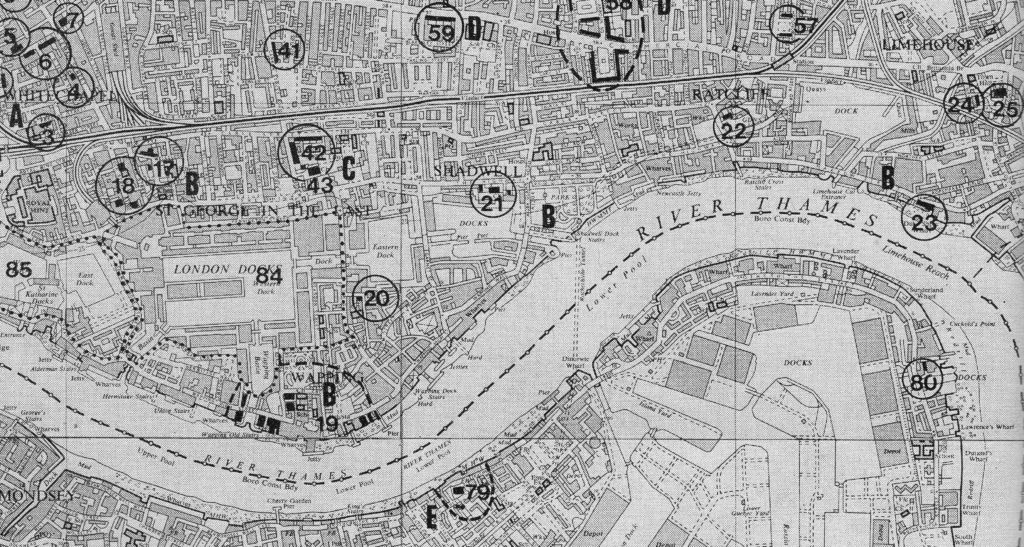

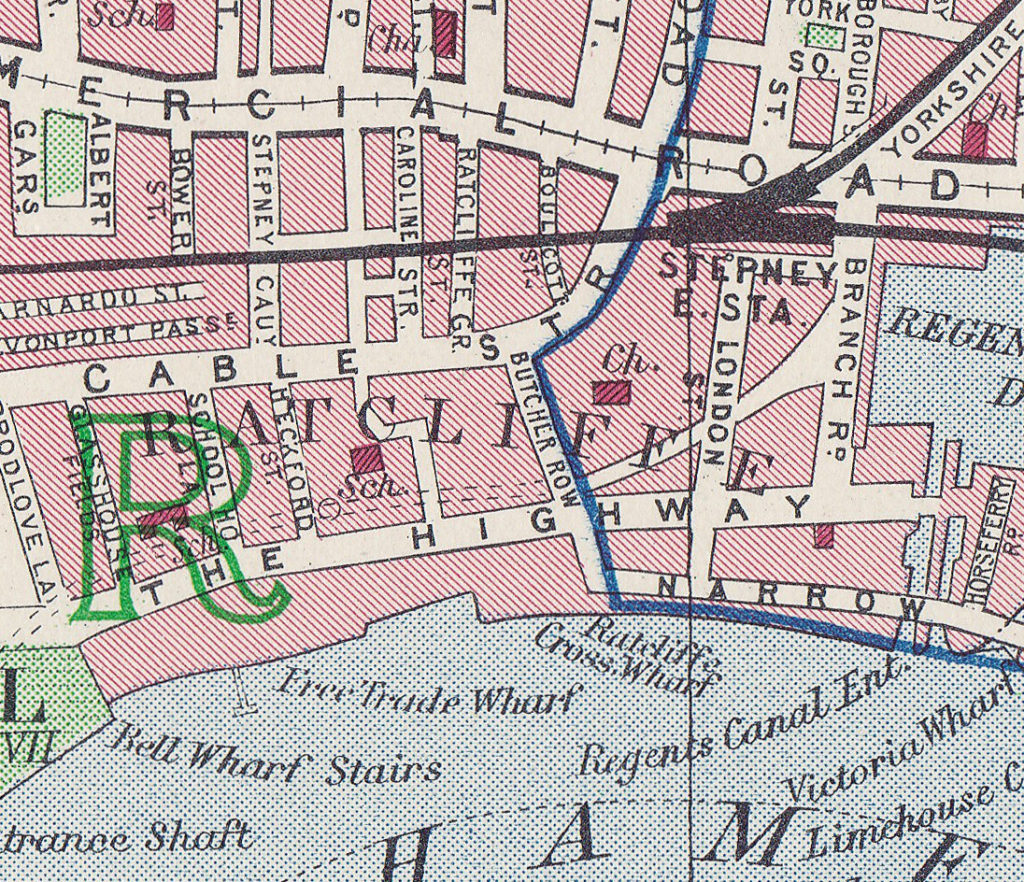

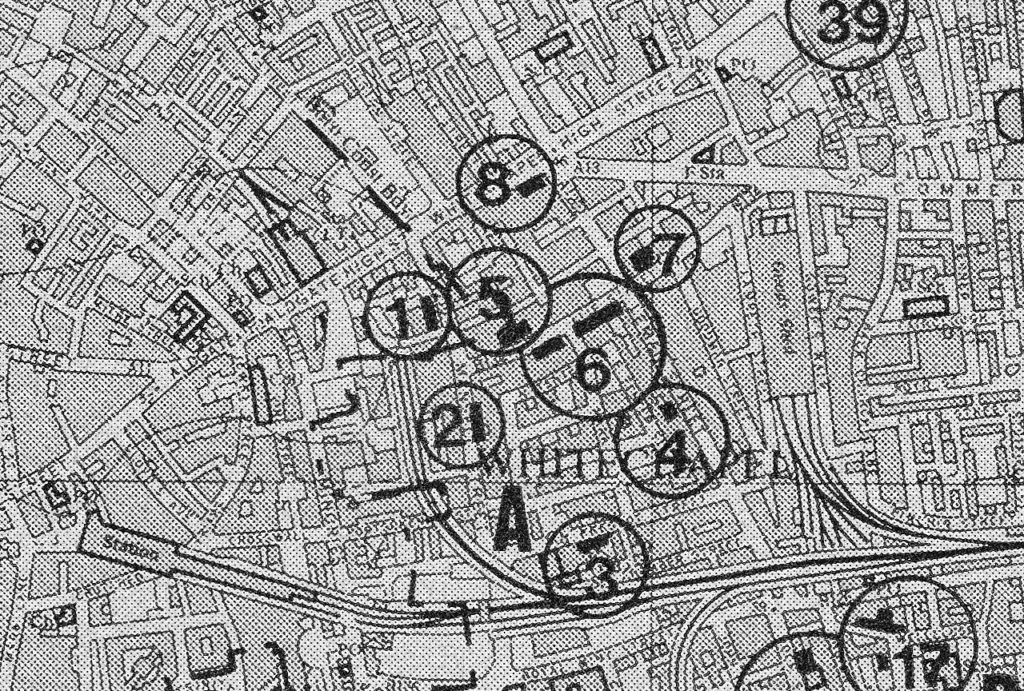

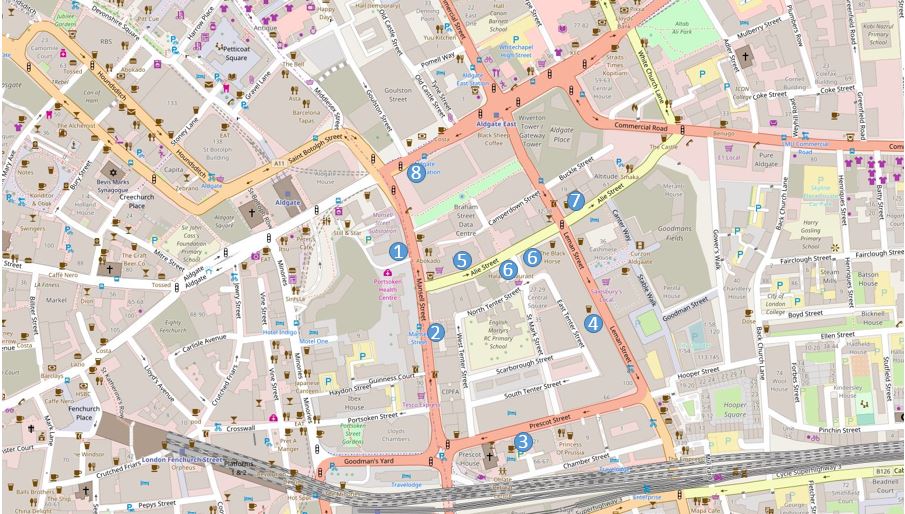

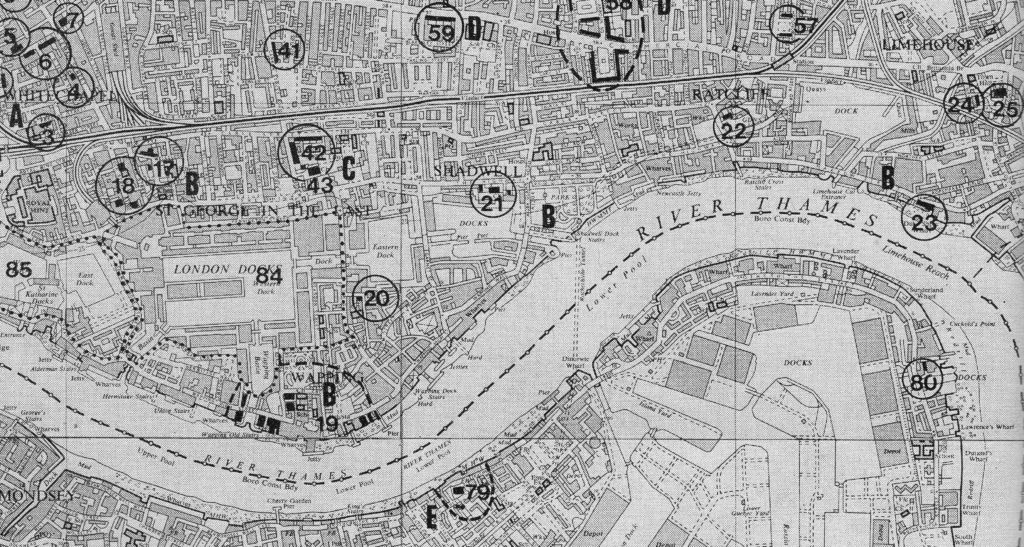

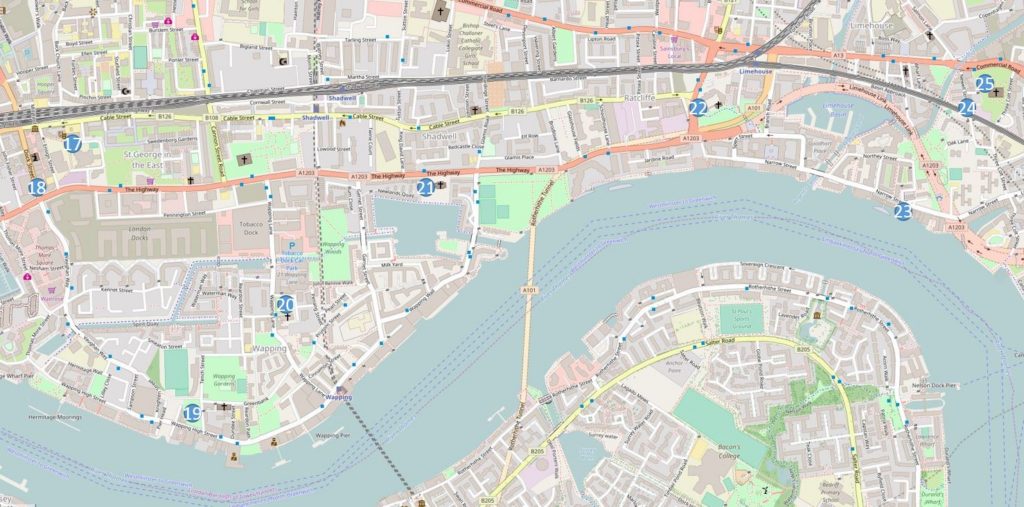

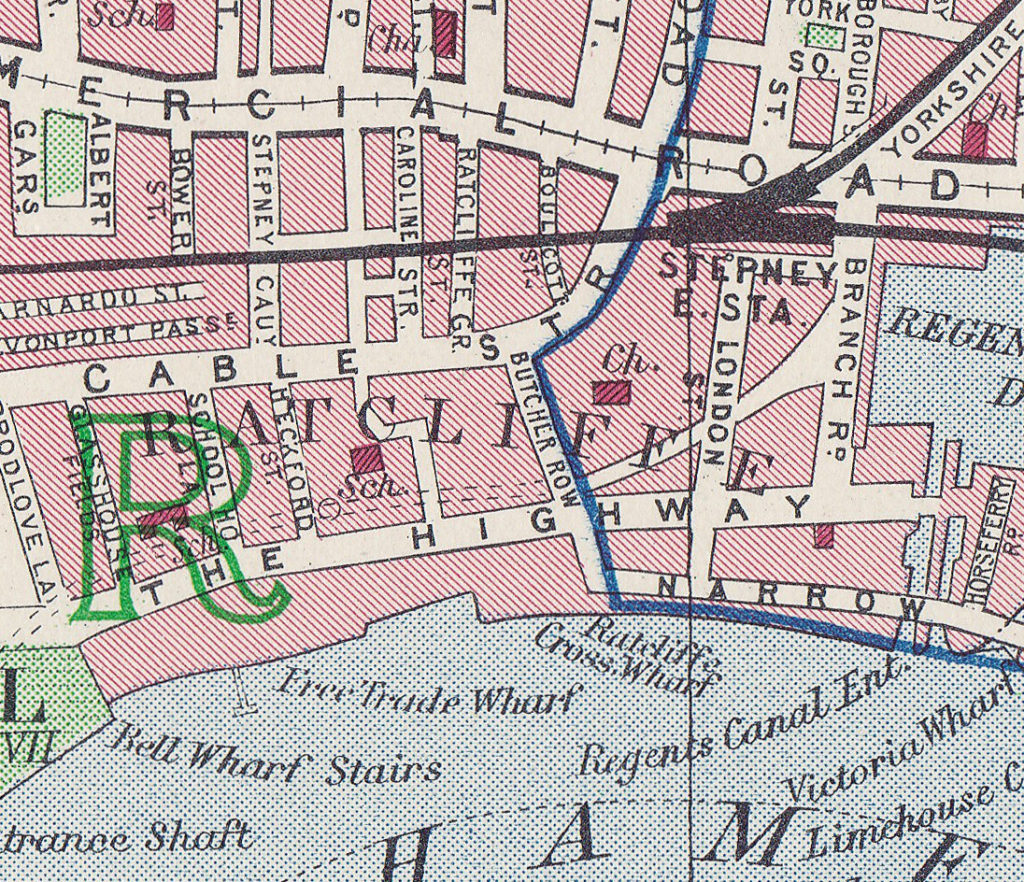

The map below is an extract from the larger map published in the 1972 article and covers the next set of locations, those marked from 17 to 25, running from the southern edge of Whitechapel to Limehouse along the Thames. The sites along the River Lea will be the subject of a later post

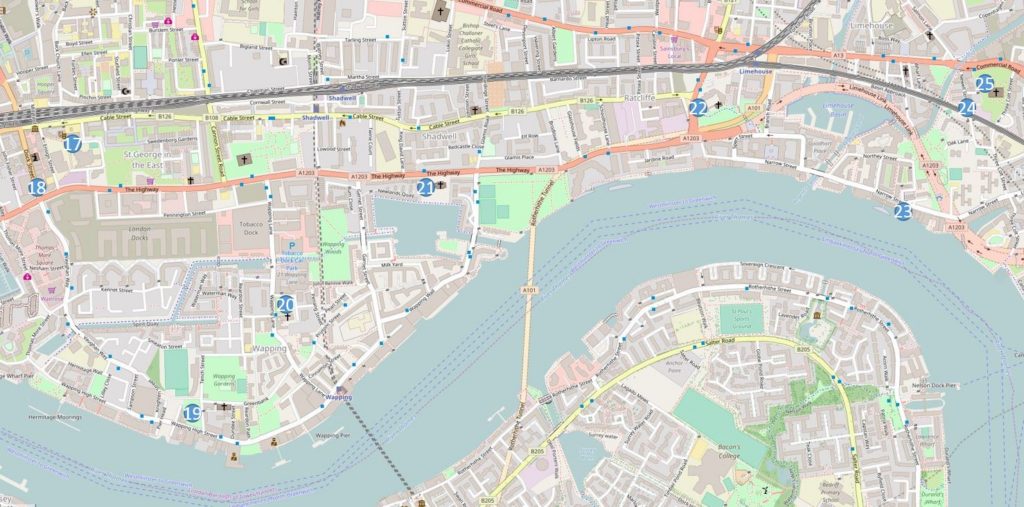

The following map shows the same area today with the same locations marked.

The Architects’ Journal introduces this area as follows:

“And now the route east from the City can be followed by tracing the riverside developments. While land east of the City still consisted of fields dotted with small, independent villages, the riverside was already lined with a continuous strip of workshops, wharves and houses. As England’s trade and empire increased in the 16th and 17th centuries, riverside villages grew in size, not inland, but along the river, and eventually became an almost independent naval town stretching from the Tower to Limehouse. This independence from the rest of London astonished even 18th century Londoners. John Fielding wrote in 1776; ‘When one goes to Rotherhithe or Wapping, which places are chiefly inhabited by sailors, but that somewhat of the same language is spoken, a man would be apt to suspect himself in another country.’ And Boswell was recommended by Johnson to explore Wapping to see ‘ wonderful extent and variety of London.’ When Boswell did go to Wapping, almost 10 years later, he was disappointed and supposed that standardisation in building had destroyed its character. “

There is so much to be written about this area, however my posts are often getting rather long, so today I will concentrate on finding the sites, and write more about the history of this fascinating area in some future posts.

I always enjoy a walk in East London and when I walked this route the weather was perfect, although bright sun can cause problems with the contrasts between sunlight and shadow in some of the narrow East London streets. Starting off, I walked to the first point:

Site 17 – All that remains of Wellclose Square and 1850 GLC owned Wilton’s Music Hall in Grace’s Alley

I started off walking along Royal Mint Street, then Cable Street before turning off down Ensign Street where the entrance to Graces Alley can be found. It is here that Wilton’s Music Hall can be found.

The buildings that now house Wilton’s have a long history. Originally individual houses from the late 17th Century they have since been through many alterations and changes, a 19th century Music Hall, a Methodist Mission and a warehouse for rag sorting.

During the 1960s the London County Council planned to demolish the whole area including the nearby Swedenborg and Wellclose Squares along with the buildings that housed Wilton’s Music Hall. Whilst the other areas under threat of demolition did not survive, the buildings along the northern edge of Grace’s Alley, including Wilton’s Music Hall were spared, but fell into dereliction. Campaigns during the last few decades raised the funding to restore Wilton’s and it is the restored building that we find today. There is a full history of the building and the restoration on the Wilton’s web site which can be found here.

Wellclose Square is a different matter. The square is found at the end of Grace’s Alley:

In the 1972 article, the Architects’ Journal describes Wellclose and the adjacent Swedenborg Square’s:

“Off Cable Street were two early 18th Century squares – Swedenborg and Wellclose Squares – neither of which descended into the slum that Cable Street had become. Both escaped serious war damage but, although unique, were not spared by wholesale demolition that occurred in the last decade. Swedenborg Gardens now stand on the site of the square, no trace of which has remained. Wellclose Square (where Dr. Johnson’s friend Dr. Mayo lived – and which at that time was the residential centre for Scandinavian timber merchants and boasted a Danish Church) has not even been rebuilt, but lies as the demolition men left it. Sites of original houses are used as car parks. The East End as an area could not afford to lose these houses; their demolition destroyed vital community memory and identity.”

The last sentence in the above paragraph is a consistent message throughout the 1972 article. It is not just the buildings that are being lost, but also the loss of a community that had long considered East London as home.

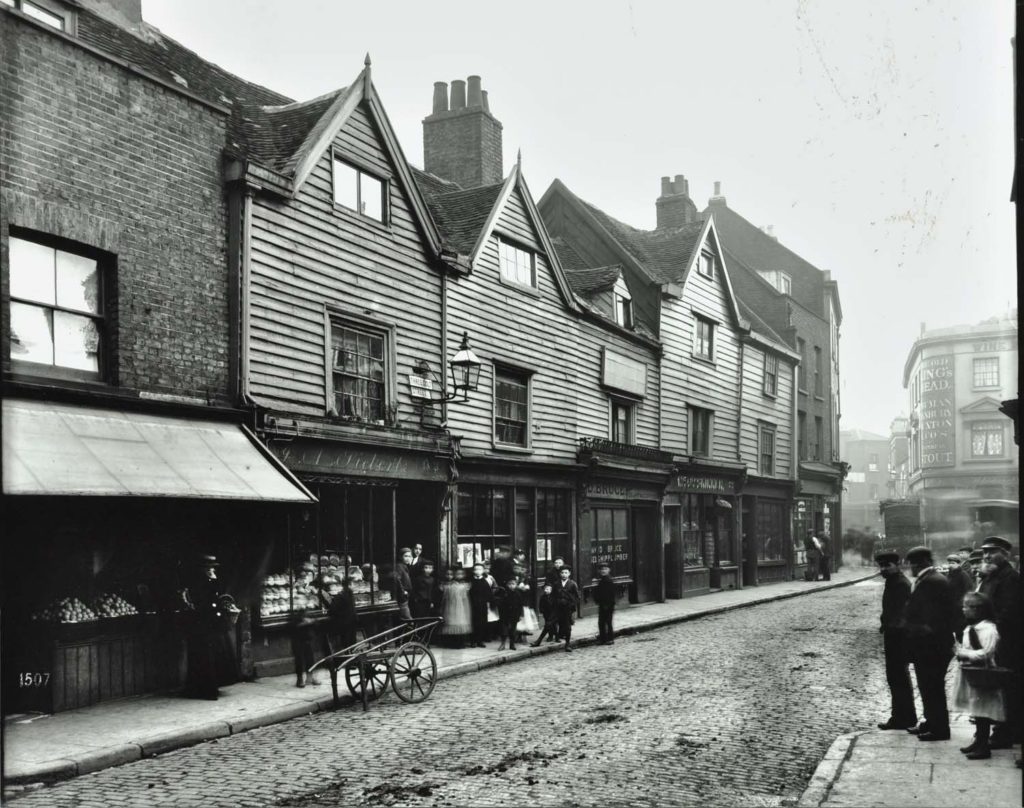

I was not sure what I would find in Wellclose Square. The Architects’ Journal listing states “all that remains” which is not very specific. The article also includes the following photo of some of the houses in Wellclose Square but does not make clear whether there were still remaining in 1972.

The buildings on the right of the above photo with the panels above the ground floor windows were originally the Danish Embassy.

A quick walk around Wellclose Square confirmed that all the buildings of the original square have been demolished, with new building from the later decades of the 20th century now running along the sides of what remains of the square.

The only buildings of any age that are now within Wellclose Square are those that form part of the central square (the original location of the Danish church). One of which is this building:

It appears to be within the grounds of the school that occupies the central part of the square so I hope that the windows and door facing the road are covered in this way to prevent access from the road rather than that the building has been abandoned.

The plaques on the wall provide some background to the building. The plaque on the left reads “St. Paul’s Mission Room” and that on the right “St. Paul’s Church for Seamen Infant Nursery”.

The building was constructed in 1874 and is currently Grade II listed. As this was a mid-Victorian building I suspect it was not what the Architects’ Journal was referring to and that all the buildings were demolished.

To get to my next location, I needed to retrace my steps to Cable Street and at the junction with Royal Mint Street turn left down Dock Street:

Site 18 – Late 18th Century Houses in Dock Street

The Architects’ Journal map shows three locations in Dock Street. One a short distance down on the left, one further on the right then one at the junction with The Highway, and it here that I will start.

The following photo shows the house in the location marked on the map, so what appears to be a fine survivor, although I am not sure whether the full house survives. If you look at the new building to the left, it appears to carry on into the original building and checking an aerial view it looks that the new building on the left extends across the rear of the older building and that whilst the front and part side facade looks to have survived this may well be a case of the body of a building being gutted and rebuilt as part of a new, larger construction.

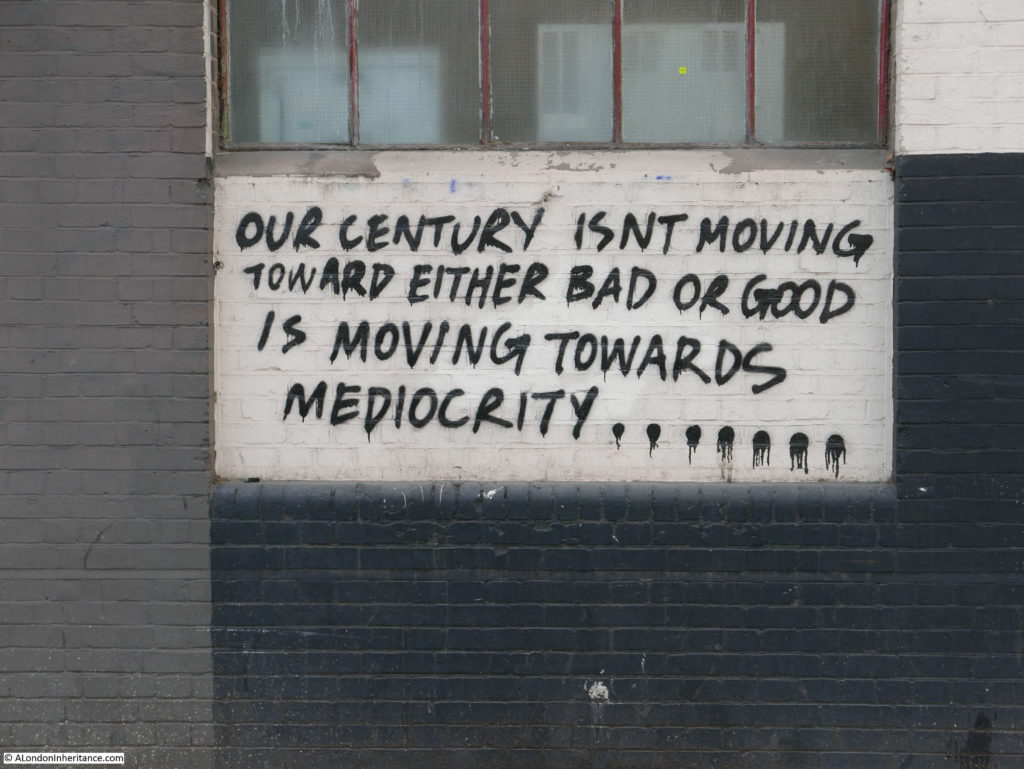

Although nothing could prepare me for what I would find next. This is the building on the site marked on the left of Dock Street.

This has to be the worst reconstruction of a pretend 18th Century house that I have ever seen. The building also has a distinctly industrial feel with the metal door, air vents and pipework down the side. Openstreetmap has this building labeled as a mobile phone company so I suspect it houses equipment for their network, but why build the front facade to possibly resemble the 18th Century house that once stood here in such a superficial manner?

Walking back up Dock Street towards Cable Street there was some considerable building work underway. Here all the buildings to the right of the Sir Sydney Smith pub have been demolished.

The full site is in the photo below. This building site will soon become the Ordnance Building where “no expense has been spared in curating a collection of residences that live up to the development’s prime location”. The Ordnance Building will also feature a “Quintessentially (online) concierge service” whatever that is.

It seems that almost anything these days is “curated”. You can read more about the Ordnance Building here.

The final location in Dock Street appears to have survived intact. A fine three floor house. Note the way that the size of the windows reduce from ground to top floor.

From Dock Street it was then a walk down towards the River Thames, to the next location:

Site 19 – Wapping conservation area enlarged to take in early 19th century pair on river to east

Site 19 covered a number of buildings around and to the east of the Wapping basin entrance to the London Docks. The docks are long since closed, however the buildings remain, some much restored and rebuilt, however the area does retain the character of when the docks were in operation.

I have already written about this area in my post on The Gun Tavern, so as this is a rather lengthy post I will not repeat here.

At the time of the 1972 article, the restored buildings along Pier Head shown in the photos above and below were for sale with prices of:

Houses: £22,500 to £37,500

Flats: £13,500 to £42,500

A quick check for recently sold prices, found that in 2012 a terrace house at Pier Head sold for £2,550,000 and in 2011 a flat sold for £1,300,000. That is quite some investment in 40 years.

Looking across to the old St. John’s Church and the Charity School next door.

The next stop on the Architects’ Journal map was reached after walking along Wapping High Street, up Wapping Lane then turning into Raine Street to find:

Site 20 – 1719 School in Raine Street

Apart from the nearby church of St. Peter’s London Docks, the old school building, or Raine House as it is now named is the only survivor among an area of redeveloped 20th century housing.

The building was originally a charity school founded by Henry Raine, owner of a Wapping brewery with the traditional blue coated school children standing in alcoves on the front of the building, very similar to the charity school in the Wapping Conservation Area.

The plaque above the door confirms the date of 1719 and states “Come In & Learn Your Duty To God & Man”.

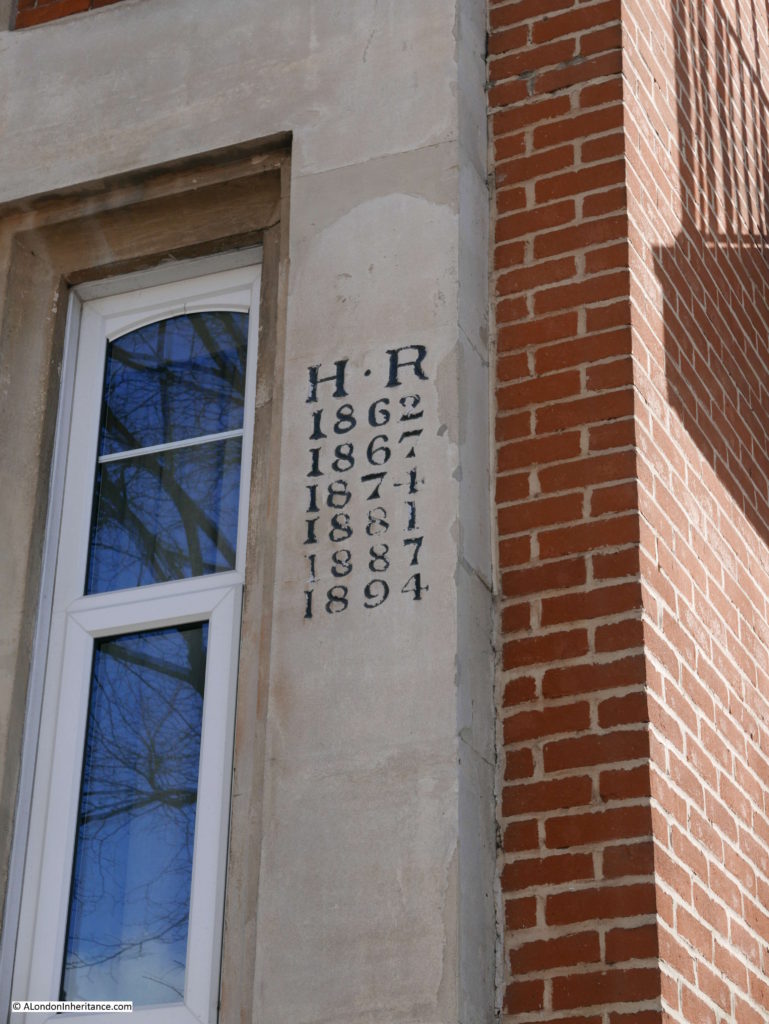

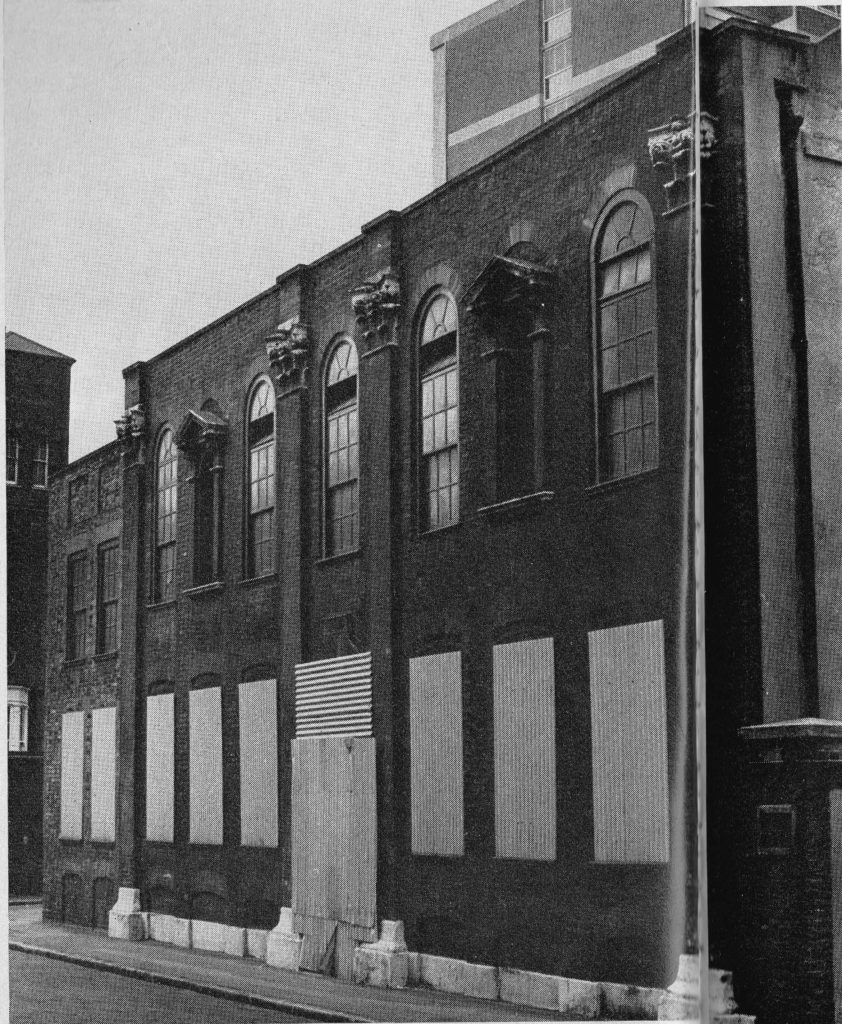

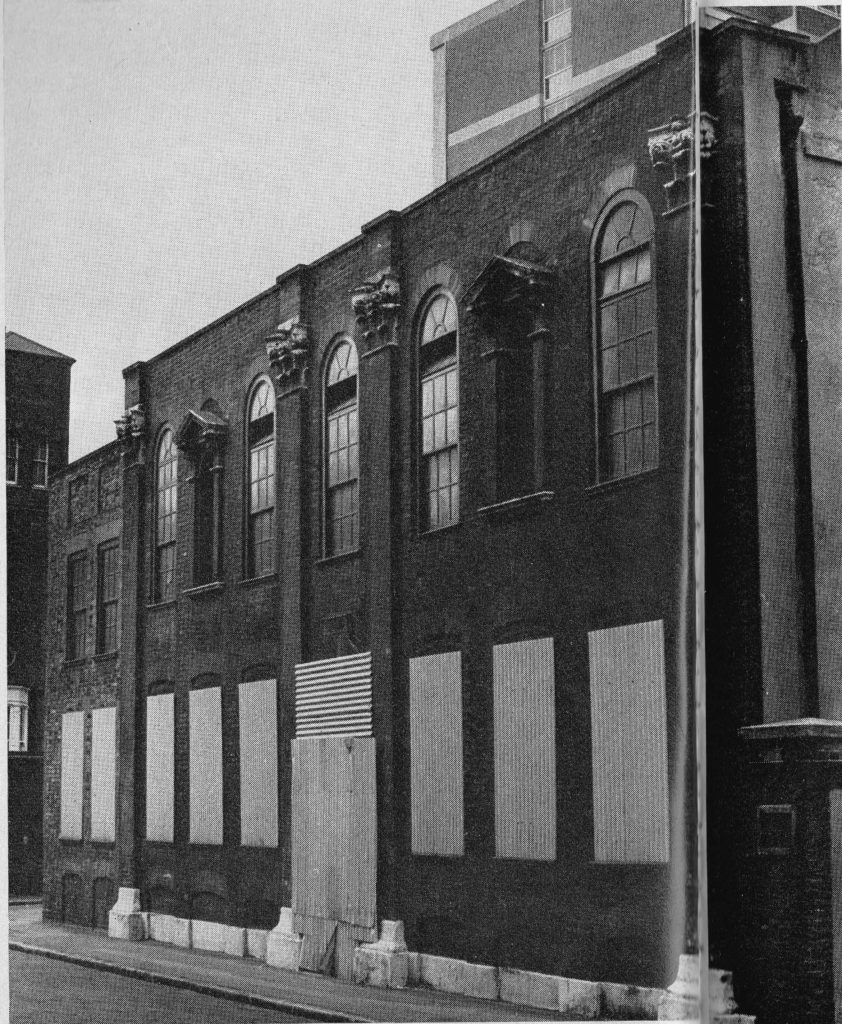

In 1972 the old school building looked to be at considerable risk. The Architects’ Journal states: “The 1719 school in Raine Street, owned by the GLC, this school is for sale – a sale that had better be quick if it is to survive attacks from the local children”. The article includes the photo below to demonstrate the poor condition of the building. Note also that the two statues are missing, hopefully moved to preserve them. The article then goes on to state “Since this picture was taken all first floor windows have been broken. What will become of this building if action is not taken soon?”

The last sentence sums up the concern that is a theme throughout the article. There were a whole range of important 18th century buildings across East London being left to decay, helped in that decay by vandalism. If the authorities did not apparently see the importance in these buildings no wonder the local children could see no reason why they could not use these decaying buildings for stone throwing and other general damage.

Fortunately the school buildings have survived and now rather suitably are home to the Pollyanna Training Theatre and Studios, rather than expensive flats.

From Raine Street, it was then a walk up Wapping Lane to The Highway to reach the next location:

Site 21 – Early 19th Century Rectory and Church of St. Paul’s Shadwell

The Highway is a really busy road and it took a while to get a suitable break in the traffic to take the photo below showing the Rectory on the right and the church on the left.

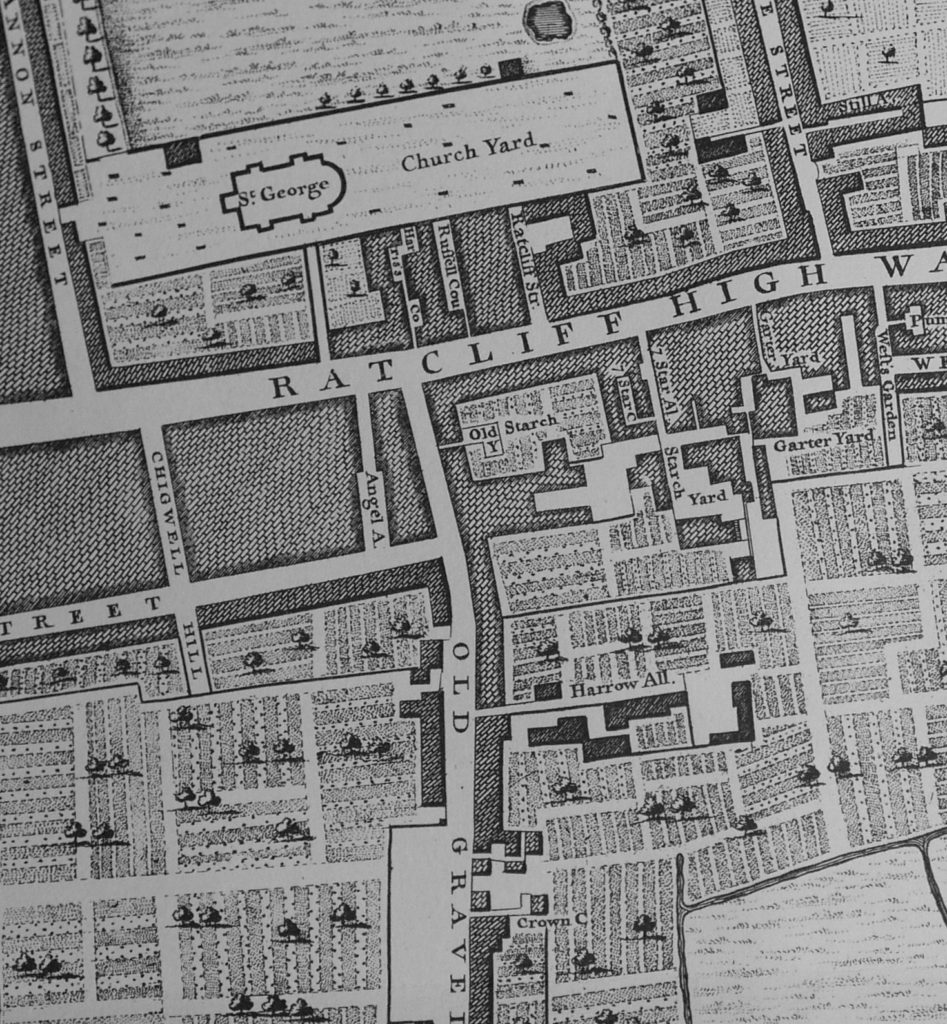

The current church is the third that has occupied the site. The original church was built in 1656 as a Chapel of Ease. This was rebuilt in 1669 as the Parish Church of Shadwell.

The 1669 church (the middle picture in the top row in the print below) was demolished to make way for the current church which was built in 1820.

St. Paul’s Shadwell has been traditionally associated with Sea Captains and Captain James Cook was an active parishioner at the church.

An information panel at the entrance to the church also records that John Wesley preached at the church and there were a number of notable baptisms including Jane Randolph, the mother of the US President Thomas Jefferson, and James Cook, the eldest son of Captain Cook.

If you look back at the maps at the start of this post, the church is just north of the Shadwell Basin and when this easterly part of the London Docks was constructed, part of the church yard of St. Paul’s was lost to make way for the new docks.

From here, I continued along The Highway, almost to the entrance to the Limehouse Link Tunnel, before turning left into Butcher Row to find:

Site 22 – late 18th Century Rectory in Butcher Row

Butcher Row is a really busy road. It links Commercial Road, Cable Street and The Highway and is at the point where The Highway disappears below ground as the Limehouse Link. The late 18th century Rectory was easy to find, but I had to wait sometime before I could get a photo not obstructed by traffic.

This is a lovely building, built between 1795 and 1796, not originally as a Rectory, but for Matthew Whiting, a sugar refiner and director of the Phoenix Assurance Company.

There was originally a church behind the Rectory building. St. James, Ratcliffe was the first church built by the Bishop Blomfield Metropolitan Churches Fund and consecrated in 1833. It was badly damaged during the war and demolished in the 1950s.

The following extract from the 1940 Bartholomew Atlas of Greater London shows the pre-war area with the church in the centre of the map with Butcher Row just to the left. The map also highlights the changes in the area. Today, Butcher Row is a much wider road and has taken over the part of Cable Street where it runs up to Commercial Road.

The Rectory and the area once occupied by the church is now the home of the Royal Foundation of St. Katherine.

On the front of the rectory is a blue plaque to the Reverend St. John Groser, an East End Priest during the first half of the 20th Century who took part in the General Strike and was injured in the Battle of Cable Street. There is a fascinating history of St. John Groser to be found here.

Hard to believe that this house is facing one of the busiest sets of roads in East London.

Leaving the traffic of Butcher Row, it was time to head to the next location:

Site 23 – Early 18th Century Group in Narrow Street

This group of buildings are still looking in fine condition and include The Grapes pub.

the Architects’ Journal provides a view from 1972 of how this type of house could survive and the social changes that this involved:

“In Narrow Street a few much restored early 18th century houses give foretaste of the social pattern that might soon develop along the whole riverside. the fronts are well painted, but generally anonymous, the backs, have picture frame windows and motor boats. Their original inhabitants have been moved into council flats behind.

Significantly these houses survive only because they have been bought by people able to restore and maintain them. Tower Hamlets had planned to demolish them for open space, but relented when it was agreed that they would be restored privately.”

After a quick stop in the Grapes, it was on to the next location:

Site 24 – 18th Century Terrace in Newell Street

This terrace of houses is a surprise. It is reached from Narrow Lane by turning into Three Colt Street, then turning left into Newell Street. (Newell Street was originally Church Row, but changed name, I believe, in the late 1930s) Both these streets have housing blocks from the later half of the 20th century, however as soon as you pass under the bridge carrying the Docklands Light Railway over Newell Street you find yourself in a street lined with these 18th century houses.

At the end of the terrace is St. Anne’s Passage which provides access to the church of St. Anne, Limehouse. The following photo is taken by the passage which is running to the left and shows the full length of the terrace. In the photo of the site in the Architects’ Journal, the building with the curved facade is only two storey so the top storey looks to be a later addition which the different type of brick confirms.

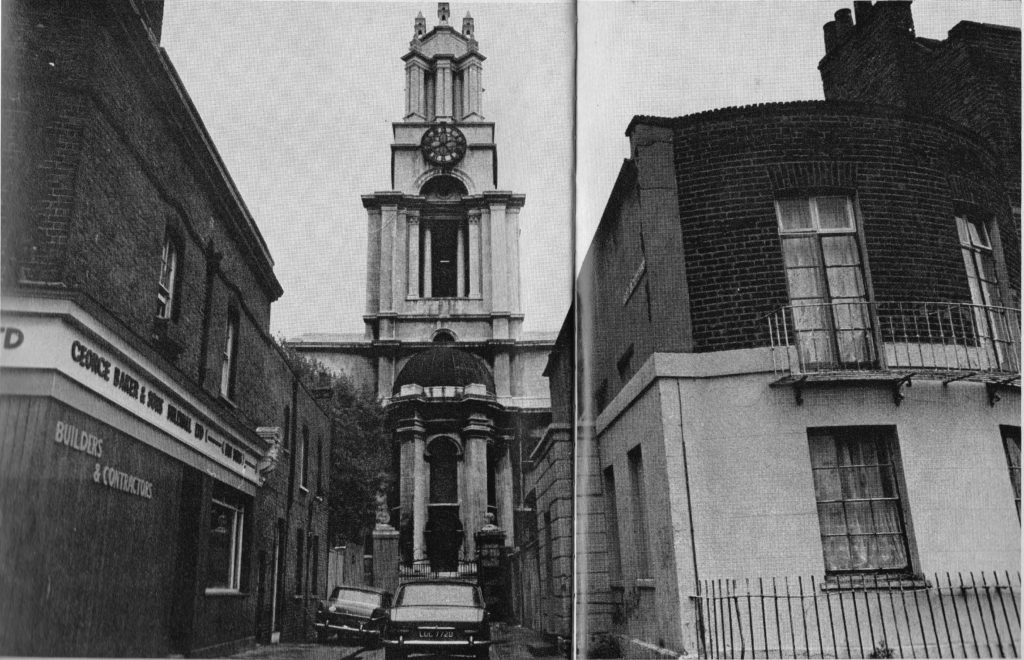

If you look down St. Anne’s Passage you find the final destination for the walk:

Site 25 – St. Anne’s, Limehouse

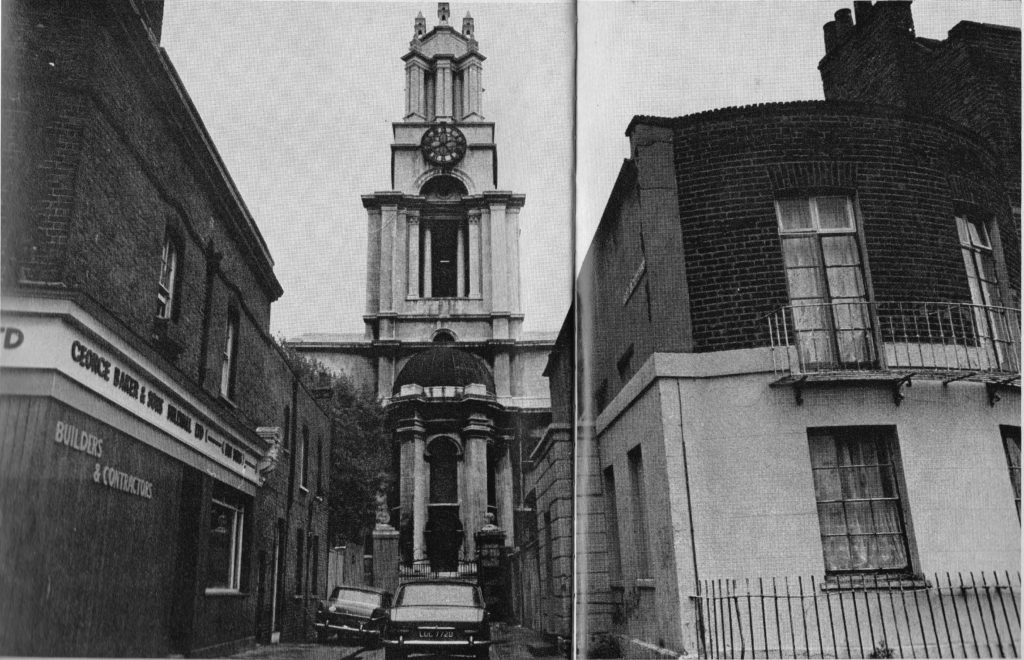

St. Anne’s Limehouse is a wonderful church and visiting on a sunny February day was perfect. Although you can enter the churchyard from the Commercial Road, the best way to approach the church is through St. Anne’s Passage which provides this view of the church:

The article in the Architects’ Journal included the following photo from the same position. Note how the house on the right was originally two storeys.

The building on the other corner was the office for a building company in 1972 however it was originally a pub which is still reasonably clear from the building today, which does not look as if it has changed much since 1972.

The pub was the Coopers Arms and occupies a good location at the entrance to the passage to the church. I wonder how may participants of a Sunday morning service walked the short distance to the pub at the end of the service?

There are so many closed pubs across East London and looking at these buildings now it is easy to forget that they were once the hub for so much of the life of the community. Most East London pubs also had sports teams and ran sports events, and despite its relatively small size the Coopers Arms was no exception.

19th Century issues of the Sporting Life tell of the events held at the Coopers Arms.

From the issue of the 22nd February 1890:

“Cooper’s Arms, Church Row, Limehouse: There was a good muster present at this establishment on Tuesday evening to witness the opening bouts of the 9st competition for a silver cup, promoted by W. Turner, the well known boxer of Limehouse. Details:

Bout 1: W. Brown beat T. Tabbits – The latter retired at the end of the first round.

Bout 2: A. Smith beat W. Potts – There was little to choose between these men, Smith receiving the verdict.

Bout 3: J. Bennett beat H. Cooper – This was a grand affair for two rounds when Cooper retired.

Bout 4: D. Hudson sparred a bye with G. Painter

Exhibition boxing by the following also took place: Willits v. Perkins, Paver v. Pointon, Walmer v. Daultry, Hall v. Barnes, brothers Campbell. Wind-up, Bill Turner v. Buffer Causer

The judges were H. Watson and H. Perry, referee T. Baldwin, timekeeper, Sporting Life representative, M.C. The finals take place on Tuesday next.”

The Cooper’s Arms also had a very active Quoits team with the Sporting Life referring to the team as “those well known East-End quoiters.”

Remove the yellow lines on the street, the street lamp and the blue sign on the gates and you could be walking to church in the 19th Century.

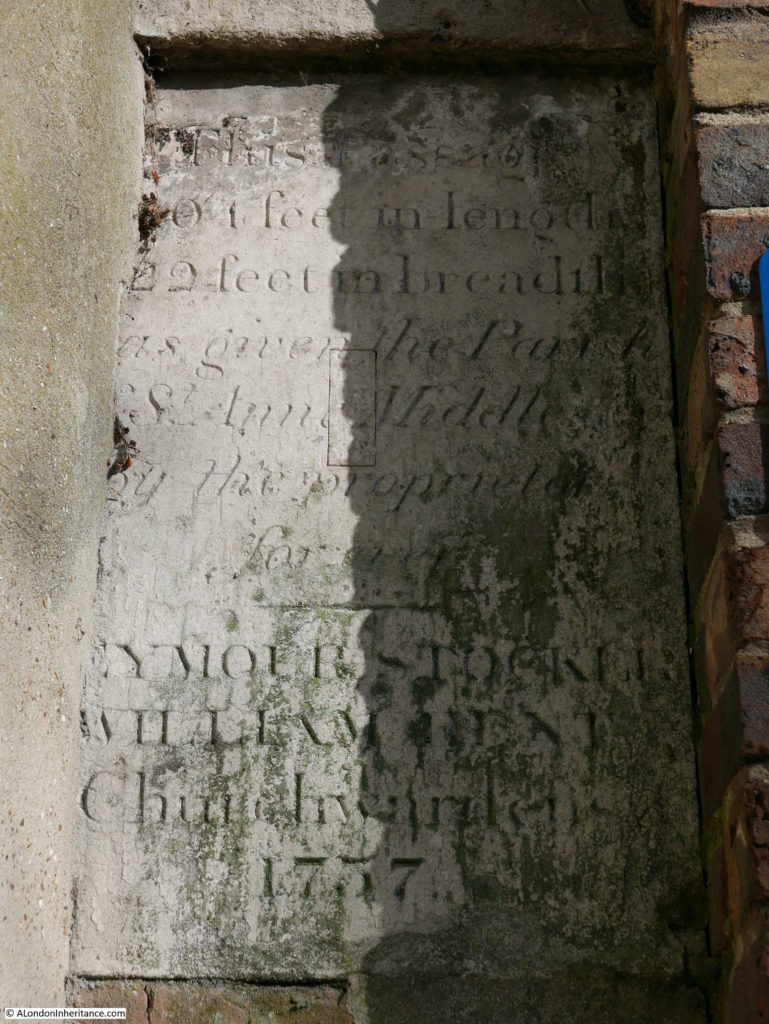

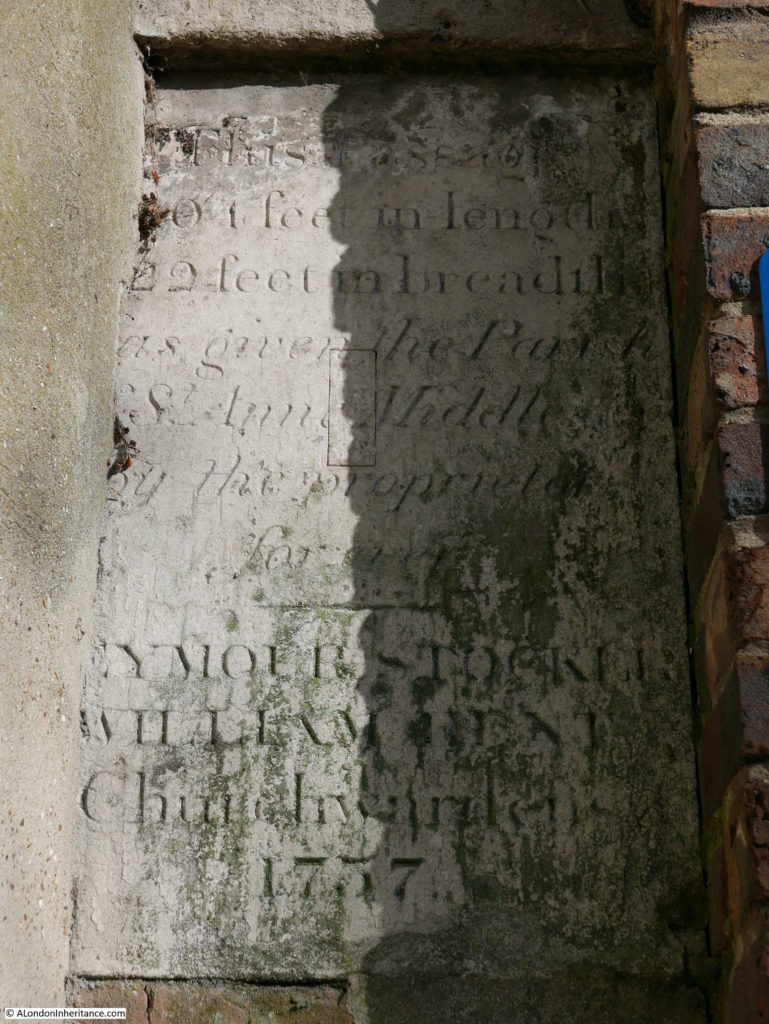

If you look just to the left of the blue plaque in the photo above, there is a much older stone plaque in the narrow gap:

If I have read this correctly, the plaque from 1757 gives the dimensions of the passage and confirms that the passage is the property of St. Anne’s Church.

St. Anne’s Limehouse is a magnificent church. It was one of the 12 churches built following the 1711 Act of Parliament to build additional churches across London to cater for the expanding population of the city.

Built between 1714-1727, the church was rebuilt after a serious fire in 1850 and there was further restoration work in the 1980s and 90s.

St. Anne’s, Limehouse was permitted by Queen Anne to fly the White Ensign of the Royal Naval Service, a tradition which continues to this day. The proximity of the church to the River Thames also meant that the church was a Trinity House navigation mark for those travelling on the river.

In the churchyard is a strange pyramid structure. It was originally planned that this would be installed on the roof of the church, however this did not happen so the pyramid continues to sit in the churchyard looking up at the church roof where it should have been located.

This was a fascinating walk, rounded off by finishing in the churchyard of St. Anne’s on a sunny February afternoon with the church yard full of crocuses.

On this third walk to visit the sites of concern in the 1972 Architects; Journal, I was pleased that the majority have survived well, the main exception being the rather strange modern mock Georgian fascia of the building in Dock Street.

The next stage will be the route from Cubitt Town on the Isle of Dogs up along the River Lea to finish of the category B locations. That is a walk for another day.

alondoninheritance.com