St Helen’s Bishopsgate, Nuns and Robert Hooke – sorry, but the post is not going to be as exciting as the title may suggest, however it does tell the story of one of the City’s ancient churches, a nunnery and some of those buried at the church.

The City churches are fascinating, not just each individual church, but the part they play in the City’s landscape, being one of the few fixed points in a thousand years of history.

Standing in front of a church such as St Helen’s Bishopsgate, it is easy to imagine the church as the time machine in the 1960 film of H.G. Wells book, The Time Machine, where the time machine is a fixed point and as the machine moves through time, the surroundings change at a rapid pace.

Or perhaps I was getting carried away by my imagination as I stood outside St Helen’s Bishopsgate last September during Open House weekend.

A church has been on the site for many hundreds of years. P.H. Ditchfield writing in London Survivals (1914) states “Several legends that are baseless cluster around the church. They tell us that the Emperor Constantine built the earliest edifice on the site of a heathen temple in the fourth century, and dedicated it to his mother, St. Helena. Some writers assert that there was a church here in 1010, but there is no direct evidence of such a building.”

The first firm, written records of the church date to around 1140, when two Canons of St Paul’s Cathedral were granted the church for the duration of their lives, provided that they paid 12d a year to the chapter of St Paul’s.

The church has a very distinctive appearance compared to the majority of other City churches. Looking at the main entrance on the west facing side of the church, a small wooden bell turret sits at the middle of two separate entrances, both with large windows above the doors.

The following print from 1736 shows the church looking much the same as it does today.

Image credit: London Metropolitan Archives, City of London: catalogue ref: q6010382

The wooden bell turret was originally added to the church around 1568, with the existing turret dating from around 1700.

The text at the bottom of the print records that St Helen was the mother of Constantine the Great. The father of Constantine was the 3rd century Roman Emperor Constantius. Helen had converted to Christianity, and when Constantine became Emperor, Helen went on pilgrimages, and also on a search for early Christian relics. She was alleged to have found the three crosses buried where Jesus was crucified, to have ordered the destruction of the Roman temple built on the site and the construction of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre.

Medieval literature included references to St Helen, trying to tie her origins into British History, including Geoffrey of Monmouth who wrote that St Helen was the daughter of a Welsh leader Coel, or Cole who legend also attributed to be a ruler of Colchester in Essex. Where there is reasonably firm evidence, it gives Helen’s origins as Greek.

St Helen’s, Bishopsgate survived the Great Fire and bombing of the City during the Second World War. The church was badly damaged during the 1990s by two IRA bombs, in 1992 in St Mary Axe, and a bomb in Bishopsgate in 1993. Both bombs caused considerable damage to the church. The architect Quinlan Terry managed the rebuild which included reconfiguration of the interior space. Aspects of the church that could not be rebuilt included a medieval stained glass window.

As the main walls of the church have not been substantially rebuilt for many hundreds of years, walking around the walls shows how they retain the echoes of so many previous features, stages of construction and a range of different building materials, frequently thrown together to build part of a wall.

The following photo shows part of the south facing wall:

A 17th century, pedimented door dated 1633 with reference to St Helena (one of the variations of the name Helen):

London: The City Churches by Simon Bradley and Nikolaus Pevsner describes the walls as of “random rubble” and this is easy to see, including where there is a range of different features which have been part of the walls over time and perhaps show where external buildings were built into the church wall. Part of the south facing wall:

The south transept extends out from the south eastern corner of the church:

Again a mix of old features and building materials along the corner of the south transept contrast with the modern office blocks that now surround St Helen’s Bishopsgate.

Within the paved area surrounding the southern edge of the church is one of the works from the Sculpture in the City initiative. This is Crocodylius Philodendrus by Nancy Rubins:

The view from St Mary Axe, showing a shaft of sunlight picking out part of the church, with Tower 42 in the rear and to the left, the tower of 1 Undershaft, and the entrance to the underground car park which now occupies much of the space to the south of the church.

I mentioned nuns in the title to the post, and it is down to a nunnery that was on part of the site for 300 years, that the church is of the form we see today. Returning to the photo of the west facing side of the church. There are two sections to the church. The section on the right of the central buttress is slightly smaller than the section on the left.

The section on the right is that of the original parish church, and on the left is the nave of the former nuns church that was added to the parish church when the nunnery was established.

This was in 1210 when the Dean and Chapter of St Paul’s gave permission to a William, son of William the Goldsmith, to build a nunnery to the north of the church, with a church for the nuns to use being added to the side of the original parish church, but being 4 foot wider than the original church.

The nunnery occupied the space to the north of the church. Returning to the book London Survivals, there is an interesting description of the church and nunnery: “The parish church, therefore, was in existence before the foundation of the nunnery, and to the parochial nave the founder of the nunnery added a second nave on the north side for the services of the nuns. This double use of the church is still evinced in its construction. It has two parallel naves divided by an arcade of six arches; and lest the eyes of the nuns should wander from their devotions, a wooden screen separated the conventual from the parochial church, the floor of which was much higher than that of the nun’s choir.

The cloister and other conventual buildings were situated on the north side of the church. in the midst of the present crowded streets and houses of modern London, it is pleasant to recall the memory of the fair garden wherein the sisters wandered. A survey taken in the time of the arch-destroyer of monasteries, Henry VIII, tells of a little garden at the east end of the cloister, and further on a fair garden of half an acre, and on the north of the cloister a kitchen garden which had a dovecot, and besides all this a fair wood-yard with another garden, a stable and other appurtenances.”

During the Dissolution, the Nunnery was taken over by Henry VIII, and Thomas Cromwell then obtained the buildings and land from the Crown, which he then sold on to the Leathersellers’ Company.

The Leathersellers’ used the refectory of the old nunnery as their Hall, and they continued to use the buildings until they were demolished in 1799 to make way for a new Hall, with offices also being built around what would become St Helen’s Place.

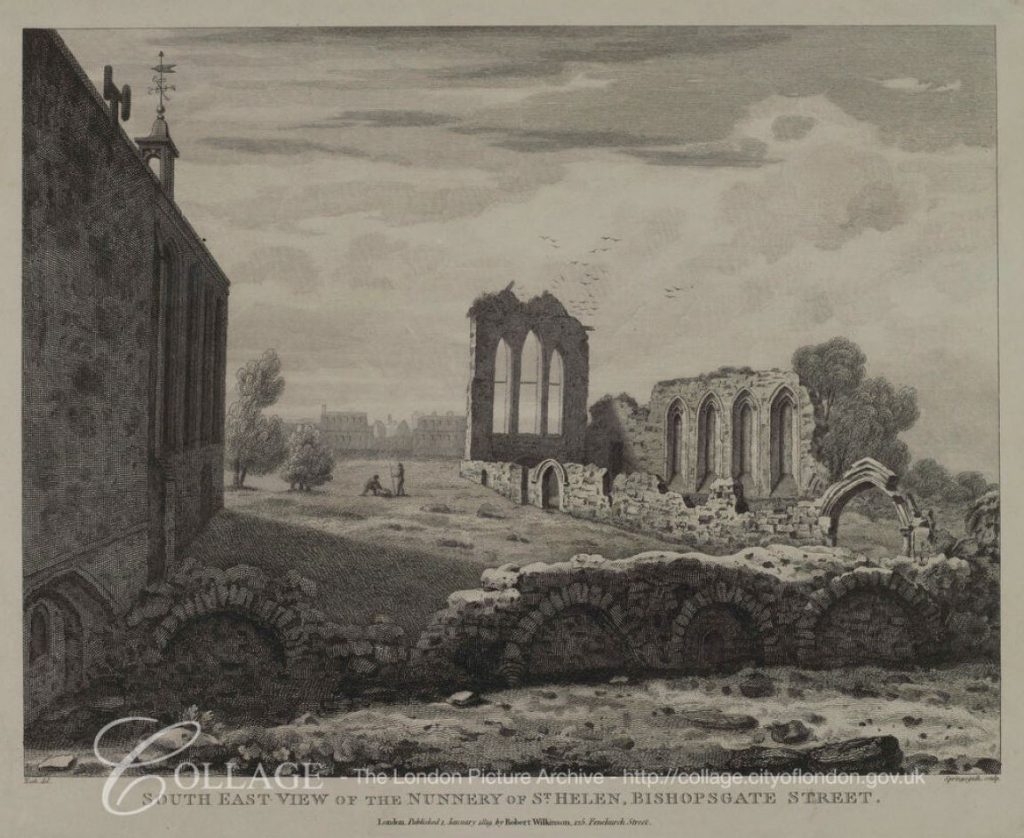

This print from 1819 shows the ruins of the old nunnery. It is a rather strange print as the area looks very rural rather than in the heart of the City. Although there is probably some considerable artistic interpretation of the view, it probably does give a good idea of the remains of part of the nunnery, with the church being seen on the left of the print.

Image credit: London Metropolitan Archives, City of London: catalogue ref: q688426x

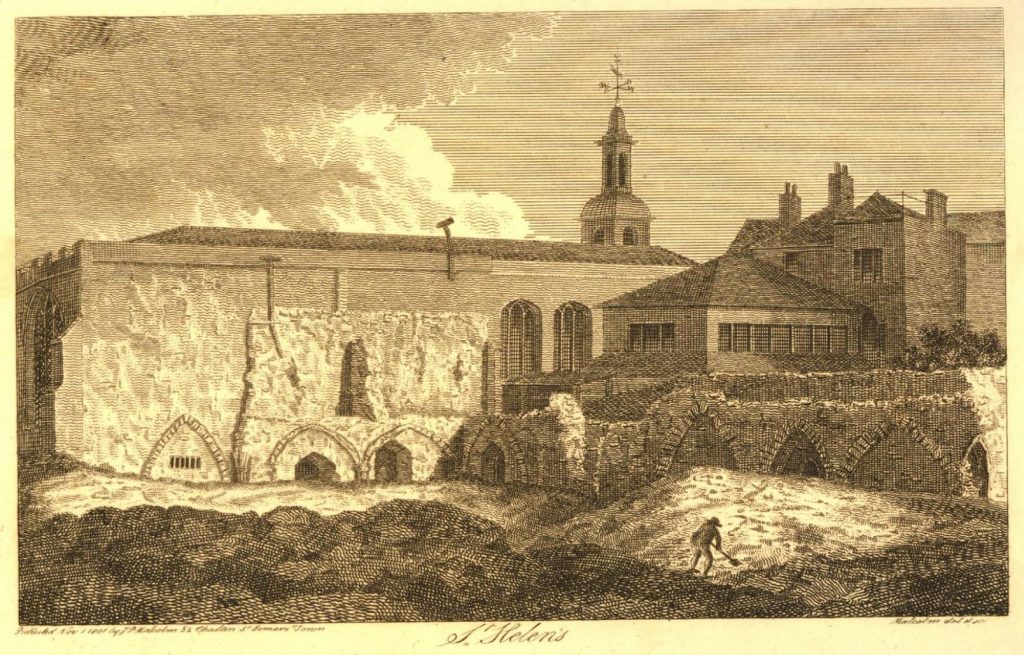

The following print from 1801 probably shows a more realistic view of the ruins of the nunnery and the church:

© The Trustees of the British Museum

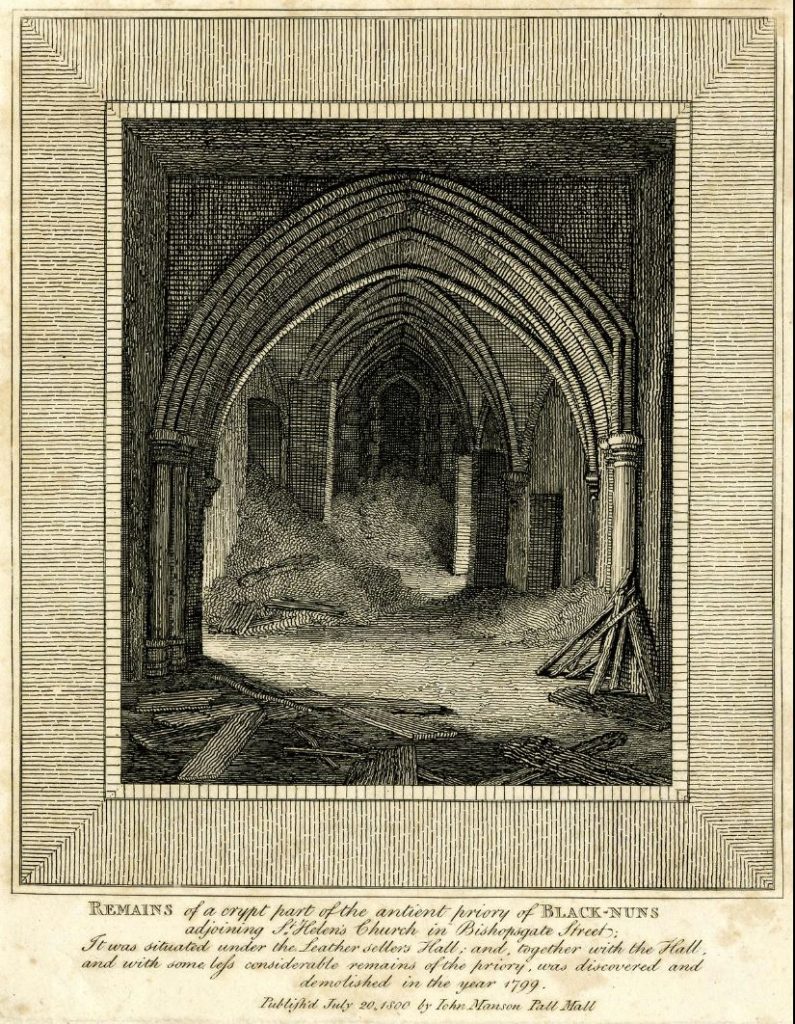

The following print dated 1800, shows the remains of the crypt of the nunnery:

© The Trustees of the British Museum

The text underneath the print reads “REMAINS of a crypt part of the ancient priory of BLACK-NUNS adjoining St Helen’s Church in Bishopsgate Street. It was situated under the Leather sellers Hall; and together with the Hall, and with some less considerable remains of the priory, was discovered and demolished in the year 1799.”

In the roughly three hundred years of the nunnery, it seems to have had the usual challenges of financial management, maintaining the behaviour of the nuns and ensuring they were separated from the general population of London, property disputes and issues regarding rights of way that ran through the grounds of the nunnery.

Wealthy London residents contributed to the upkeep of the nunnery, and in 1285 there was an event which built on the legends of St Helen. Edward I visited the church on the 4th May 1285 to deliver to the church a piece of the True Cross that had been found in Wales. Building on the legend that Helen had found the original crosses in Jerusalem, and the Welsh ancestor of Coel who Geoffrey of Monmouth alleged was Helen’s father.

Time to visit the interior of the church, which was repaired and reconfigured to provide a much more open and flexible space following the bombings of the early 1990s. The damage was such that the roof was lifted off the walls by the force of the explosions.

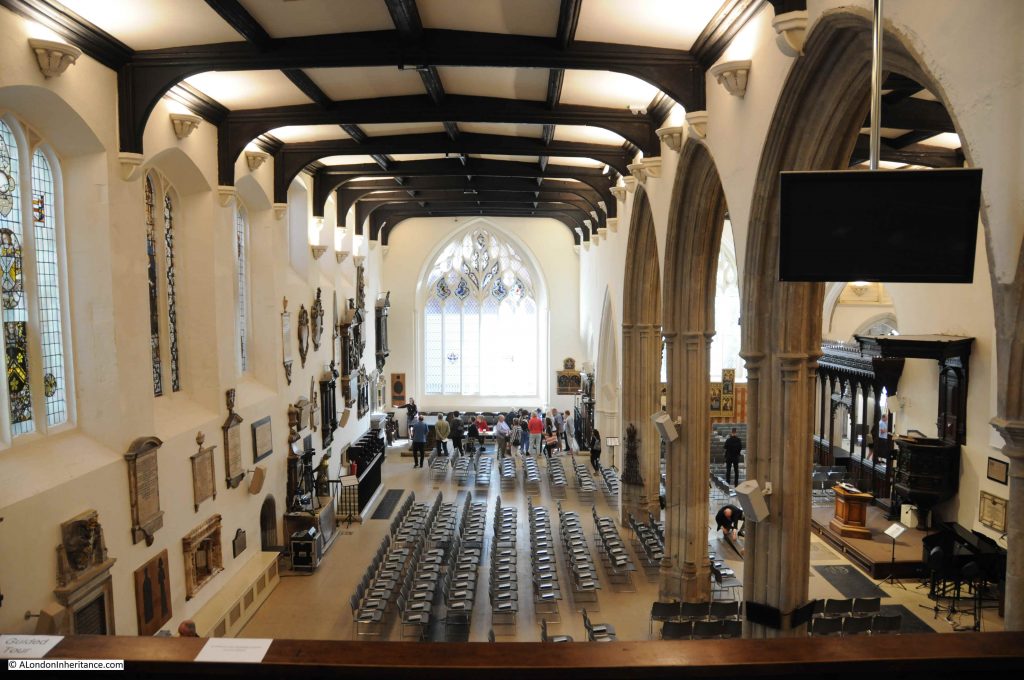

A gallery runs part the length of the western wall, and from the gallery we can get a good view along the church, showing the section of the nuns church on the left and the original parish church on the right.

The large central arches date from around 1480. Before the 1990s restoration, the floors of the various sections of the church were at different levels,some lower than at present, reflecting their different original use and periods of build. They were rebuilt to the same level in the 1990s. which does make the space easier to use, but the Pevsner Guide to the City of London Churches appears to be rather dismissive of this change, saying that “Terry remade the floor at one indiscriminately high level throughout”.

St Helen’s Bishopsgate has a large number of memorials and monuments. London Survivals records that the number of these have given the church the name “Westminster Abbey of the City”.

Many of these are fascinating, not just through the story of the subject of the memorial, but the way the story has been portrayed. This is the memorial to Martin Bond – a worthy citizen and soldier.

The text states that he was “son of Will Bond, Sheriff and Alderman of London. He was Captain in the year 1588 at the camp at Tilbury and after remained chief captain of trained bands of the City until his death. He was a Merchant Adventurer and free of the Company of Haberdasher. He lived to the age of 85 years and died in May 1643. His piety, prudence, courage and charity have left behind him a never dying monument.”

I love it when I can tie posts together, and the reference in the memorial to Martin Bond being at the camp at Tilbury in the year 1558, is a reference to Tilbury Fort which I wrote about here.

1588 was the year when additional reinforcements were made to the fort at Tilbury due to the threat from the Spanish Armada. In March of the previous year, Queen Elizabeth I requested the City to provide a force of 10,000 men, fully armed and equipped. Billingsgate Ward contributed 326 men, one of which would have been Martin Bond.

His memorial may well therefore show him in his role as Captain, in his tent at Tilbury Fort.

As well as memorials, there are bits of stonework that further demonstrate how churches of this age are made up of many different bits of stone from different sources.

The plaque at the top reads “The insertions in the wall beneath are a weathered fragment of marble of Moorish or Venetian workmanship (XII or XIII century) discovered in the interior of the Bernard monument adjacent on its removal (in 1874) to its present position. A Purbeck marble panel, part of the ancient Clitherow Monument (formerly of the church of St Martin Outwich) used to repair the Pemberton Monument on its reconstruction in 1796 and removed on the restoration of that monument in 1874”.

Monuments tell stories of the life of those recorded on the stones and marble. The monument shown in the photo below is to Dame Abigail Lawrence, who died at the age of 59 on the 6th June 1682.

She is recorded as being the “tender mother of ten children, the nine first being all daughters she suckled at her own breasts, they all lived to be of age, her last a son died an infant”. Described as an “Exemplary matron of this Cittie”.

The walls on which these monuments are now mounted are all firm and dry, but it is interesting to read of earlier improvements, the state of the walls and the problems faced by employing workmen in such a historic building.

There was an article in the London City Press dated the 22nd July 1865, reporting on the repairs and renovations that were about to take place at St Helen’s Bishopsgate. In the article, the walls were described as being built with nitrate of lime, and as a consequence being almost always wet.

The article also mentions that the church is home to a large number of brass memorials and that during the last restoration in 1845 several of these brasses were lost – the implication being that they were stolen at the request of antiquaries. The article also references the loss of large quantities of lead, stolen from the coffins by workmen, working on repairs at Stepney Church.

The article recommends that the church authorities put in place measures to protect the artifacts in the church, as “the power of whisky over the working man is very great, and it is feared that the mere value of the brass may have caused some of them to have been taken away”.

The church has a late 18th century Poor Box which is mounted on a 17th century figure of a bearded man, holding a hat ready to receive alms.

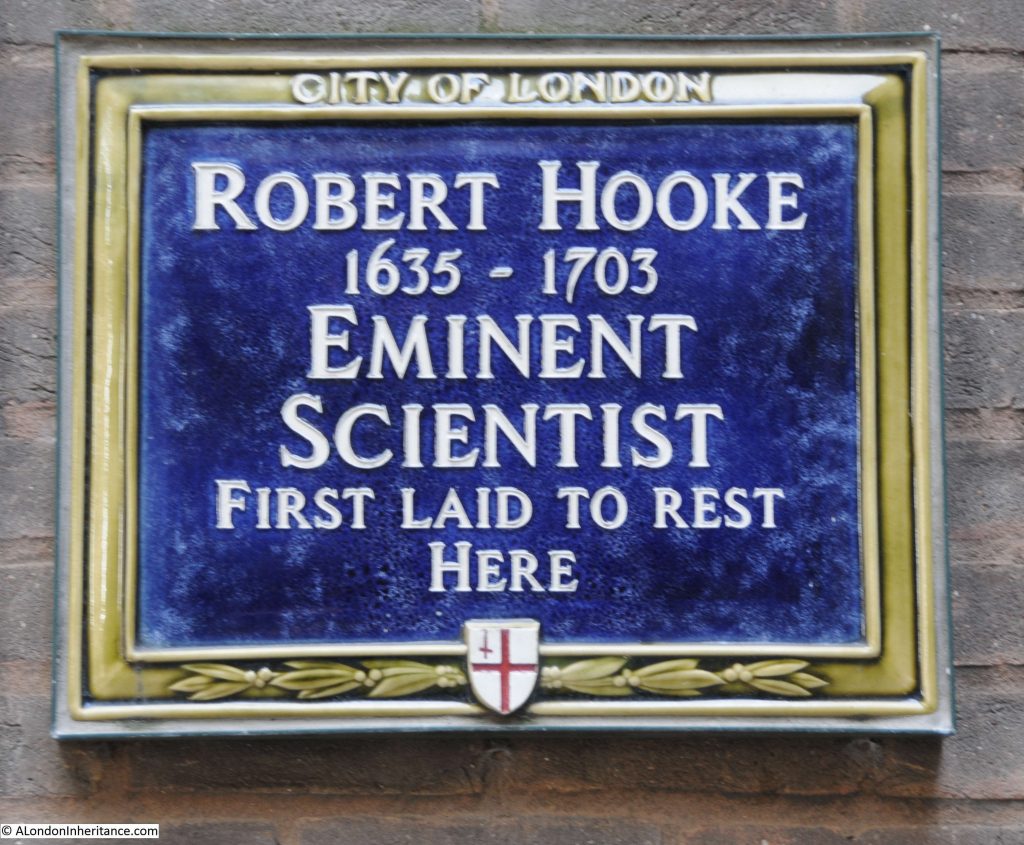

There are numerous memorials and monuments across the church, too many for a single post, and there is one further subject in the post’s title that I want to cover, one Robert Hooke.

Robert Hooke was far more than a scientist. He was also an engineer, surveyor, inventor and architect. Your first contact with Hooke may have been during school science lessons and Hooke’s law which stated that the force needed to extend or compress a spring is proportional to the distance extended or compressed.

After the Great Fire in 1666 he was appointed the Surveyor for the City of London and worked on many of the rebuilds of the city churches, frequently with Christopher Wren. This work included the Monument to the Great Fire.

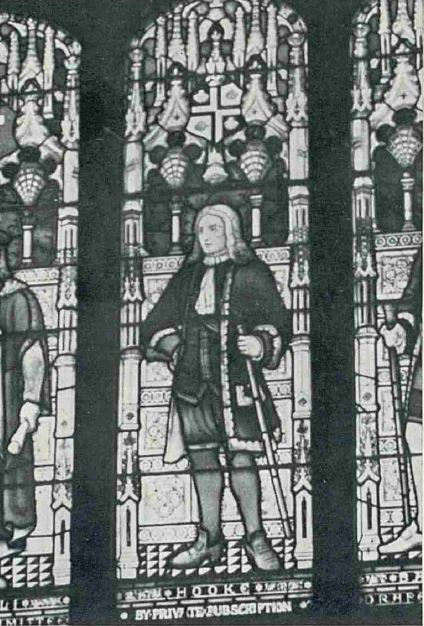

He has been somewhat overshadowed by Wren, and other scientists of the time such as Newton. He also had a number of disagreements and controversies with other scientists during his lifetime, Possibly because of these, there are no drawings or paintings of Robert Hooke which survive to this day. Apparently Newton removed Hooke’s name from the Royal Society records and destroyed his portrait after one rather passionate argument.

Hooke’s bones were removed from the graveyard at St Helen’s during the 19th century, probably during one of the many Victorian clearances of the City graveyards. They were moved to an unknown destination in north London.

There was a memorial window to Robert Hooke in St Helen’s Bishopsgate which was one of those destroyed during the IRA bombings of the early 1990s. The following is a 1930s photo of the window:

St Helen’s Bishopsgate, although surrounded by modern office blocks, has roots that stretch back across the centuries of the City’s history. Leaving the church, I was still thinking of the Time Machine, and everything the church has seen built and then demolished, and all the people who have passed through and by the church, and what the church will see in the future.