This week is the end of my third year of exploring London and of writing this blog – a point I must admit I am surprised I have reached.

My purpose is the same as when I started, to trace the locations of the photos my father took of London and to give me a push to get out and explore the city.

I would really like to thank everyone who reads, subscribes and comments to my posts. I would also like to apologise to all those who comment and e-mail as I am really bad at responding. Writing and researching a weekly post as well as all the normal work and family commitments is a challenge. When I complete one post it is then into panic mode to focus on the next post. I can only admire those who write more frequently.

As a thanks for all the comments I have received, I would like to use this opportunity to publish a small sample of comments to my posts from over the last year. I learn so much from these, they provide personal background to the locations I cover, more information about the sites, answers to questions, point out errors (thankfully not too often) and provide links to other resources including a number of fascinating films.

So, to start with a post I published in March of last year.

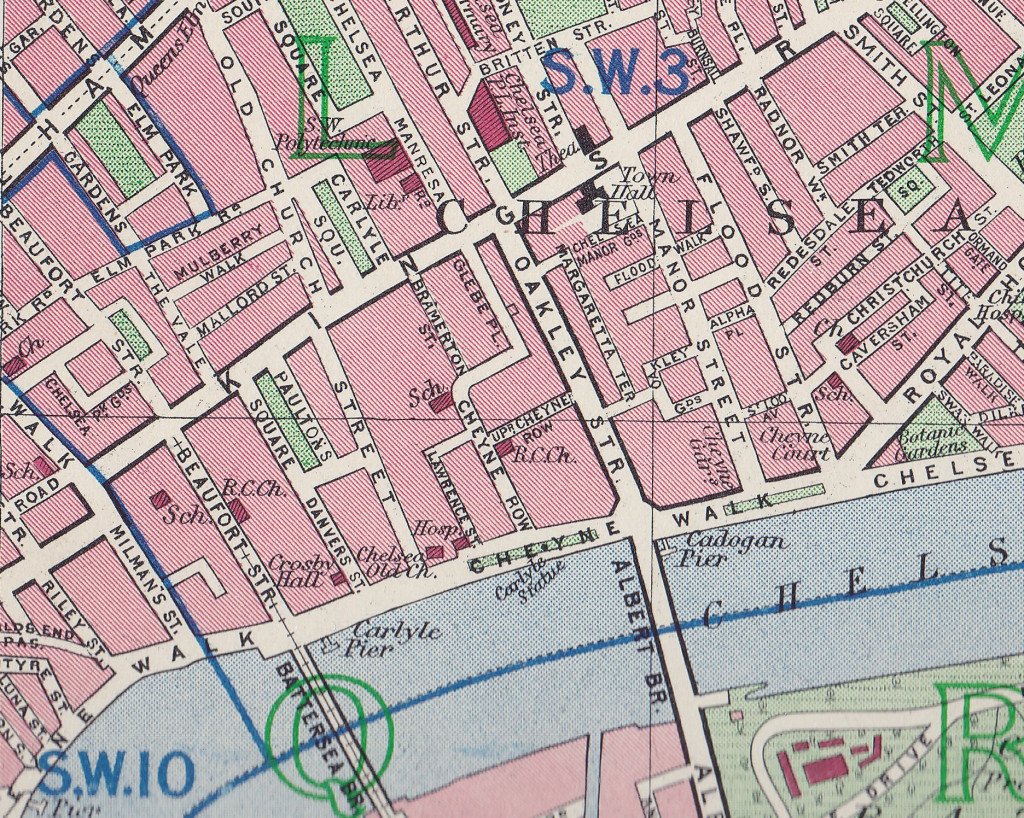

Chelsea Old Church

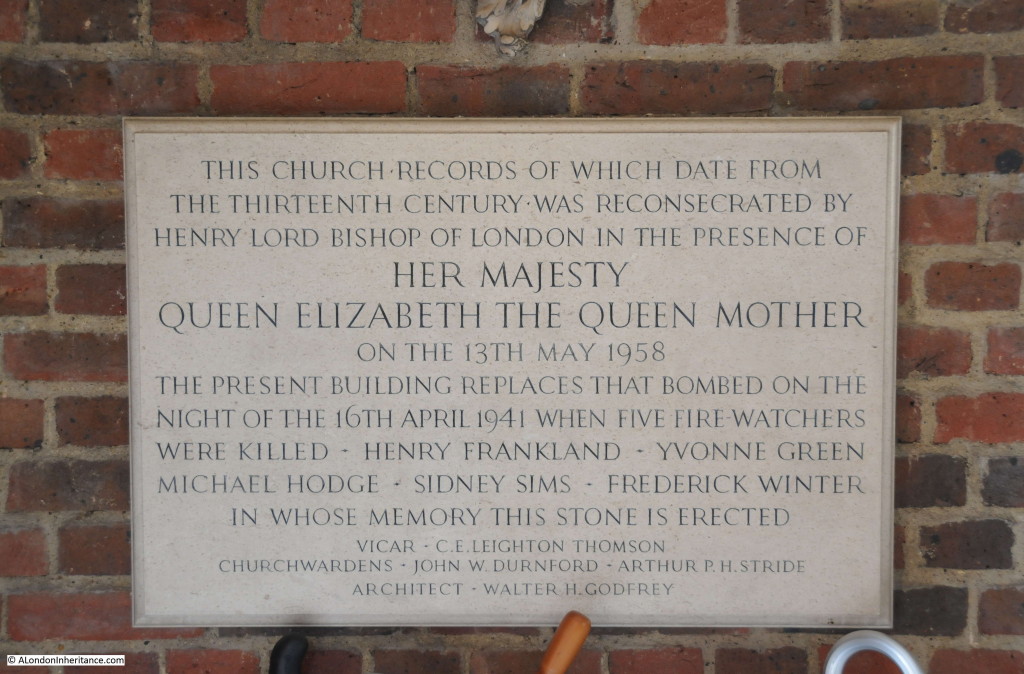

Chelsea Old Church was destroyed during the last war and my father took the following photo of the site. The church was rebuilt after the war to an identical design as the original, and many of the interior monuments were restored and now make the church a fascinating place to visit on the Chelsea Embankment.

I received a comment from Paul on his experiences around Chelsea Old Church:

I started my school life at Cook’s ground in 1939. I entered through the right hand gate on Old Church Street that had an overhead engraved stone sign saying “Girls and Infants”. The left gate’s said “Boys”. I didn’t have far to walk because we lived at Rectory Chambers almost next door. In front of our house was McCauley’s grocery. He had two girls and I went to school with them. Between our house and the school was Roma’s cafe, Rosemary was my mother’s best friend. In front was the “Pig’s Ear”. Wooden beer barrels were off loaded from horse drawn wagons and slid into the pubs cellar through a trap door in the pavement. Coal was also delivered to all the houses by horse cart and unloaded through small iron “manholes” in the pavements. The were no cars parked on the streets. Trams ran down Beaufort St. from Kings Road to Clapham Juction. A fellow on a bicycle lite the gas street lights with a flame at the end of a pole.

Then all of a sudden ALL the lights went out. My mother got a summons because a light showed through the tiny bathroom window! Like all the other windows it should have been covered with black cloth.

The year after I started school we were labeled and posted by train to Cornwall. I returned home a year later because I had contracted diphtheria. The whole area at the end of the street was now a pile of rubble and a part of the church left standing was boarded up so we could’t get in, though we tried. There were still some of my friends around and we used the bricks to make dugouts and play “war” games throwing rocks at each others trenches. I was once knocked out and awoke in a neighbor’s kitchen while the lady bathed the back of my head. I have a photo of me on the rubble with my baby brother and mother nearby. It was taken by my father before he left for Africa. A neighbor named Bill Mallett became my best friend. He drove a lorry which he had parked in next to the damaged area in front of his house. He told me what had happened while I was away. He helped my mother repair our front windows. She had tomatoes planted in flower boxes on the roof. Paulton’s Square had “victory” gardens planted around the half buried shelters there. All the railings had been removed. I hated to go down after the air raid siren sounded because they smelt so bad. The wardens allowed me to site at the door with them and watch the planes until the noise got too loud. After the “all clear” my friends and I ran through the streets looking for bombs and shrapnel. One of us found a whole incendiary so he became our leader. He took it home for his collection and never did tell his parents! I found a small bomb and we tried to set it off by repeatedly throwing it in our “war zone”. Finally it broke apart and it was filled with a yellow putty. Notices were pasted all around with photos of “booby” traps that were dropped by the Germans. They looked like toys but we never found one! I could have been one of the kids by the ice-cream cart shown above or at least they were my some of my friends.

I left Kingsley (Cook’s ground) for the last time through the left gate in 1948, Dr. George Walsh was head master.

Manchester Square, The Marchioness Of Hertford And A Very Old Lane

Then in May I wrote about Manchester Square, home to Hertford House and the Wallace Collection.

Geraldine shared an experience when walking through the square in 1969:

I lived at 25 Manchester Street (near the junction with Dorset Street) for five years, from 1968 till 1973. Back then, EMI Records occupied a post-war office building in the north-west corner of the square (since demolished). The cover shot for the Beatles’ first album shows them leaning over a street-side balcony at EMI House, grinning like cheeky chappies. Quite by happenstance, I was walking home from work through the square in 1969, saw a small crowd gathered outside EMI, looked up & there were the Fabs in their hippie pomp, being photographed by Angus McBean again, for what was intended as the cover of their album-in-progress. (It’s on the Blue Album: 1967-1970.)

And from Henry, a wonderful family link to Manchester Square:

My great-grandfather Stopford Brooke (the founder of the Wordsworth Trust at Grasmere) lived at 1 Manchester Square between 1866 and 1914. His large study was at the top of the very tall house, where he would entertain the likes of Robert Browning, Alfred Lord Tennyson, W.B.Yeats and Henry James. An unmarried sister looked after his seven motherless children, for whom Sunday lunch was the only time when they could be sure to see their father. who sat at the end of the long dining-room table. His long sermons stirred the conscience of late Victorian London.

It Can Now Be Revealed

It Can Now Be Revealed is the title to one of the many booklets published at the end of the war to record the experiences of specific organisations or London boroughs during the war and also looking forward to post war reconstruction.

It Now Can be Revealed covered British Railways and as well as covering the war, also provided a very positive view of the future development of the railways, and included this drawing of a new Finsbury Park station which will be rebuilt “on the most modern lines”.

Within the text of the booklet there was a reference to News Theatres, which I had not come across before:

“The future British railway station will incorporate as spacious a concourse as possible, equipped with all the facilities that passengers need, conveniently situated and easily identifiable. Both concourse and public rooms will be light, cheerful and attractively decorated. News theatres (no idea what these were), newsagents, fruiterers, chemists, confectioners shops and Post Office facilities will be included whenever needed. Special attention will be given to the standard of food, drink and service provided in the refreshment rooms. Finally the platforms will be kept as free as possible of obstructions and passengers given the clearest indication and guidance about their trains, and how to get to them, by means of carefully designed train indicators and signs, supplemented by loudspeakers.”

I had some feedback about News Theatres, from M D West:

News Theatres were small cinemas for showing film newsreels etc….they built one in the Queens Building public foyer at Heathrow (opened 1956) and I think there was one at Victoria Station.

From Colin:

There was certainly a news cinema at Victoria Station, the entrance was shared with the parcels’ office on the Buckingham Palace Road side and was parallel to the road. I used to walk there to see the ‘toons in the ’50s it must have been

From Anne:

Up until the 1970s or so it was common to be able to walk in and out of a cinema at any point in the performance, so I guess the idea of a news theatre (in pre-TV days) at a station would be to pop in and pass the time while you waited for your train.

And from Guy which included a link to a photo of the Victoria Station Cartoon Cinema as the News Theatre became:

Here’s a link to details of the news cinema at Victoria Station that later became a cartoon cinema, before shutting in 1981:

http://cinematreasures.org/theaters/1248/

Smith Square – Architecture, History, And Reformers

In June I went to Smith Square.

Eddie wrote with his experience of working in the area and gave me a challenge I have not yet completed:

I spent many many hours walking around it during the 1970’s being a Police Officer at Rochester Row. Harold Wilson, Prime Minister twice, used to live at number 5 Lord North Street and he and the house had 24 hour armed protection, just one of many armed protection posts on Rochester Row and Cannon Row’s ground. Next time you visit see if you can find the two ‘ducks’ in Smith Square.

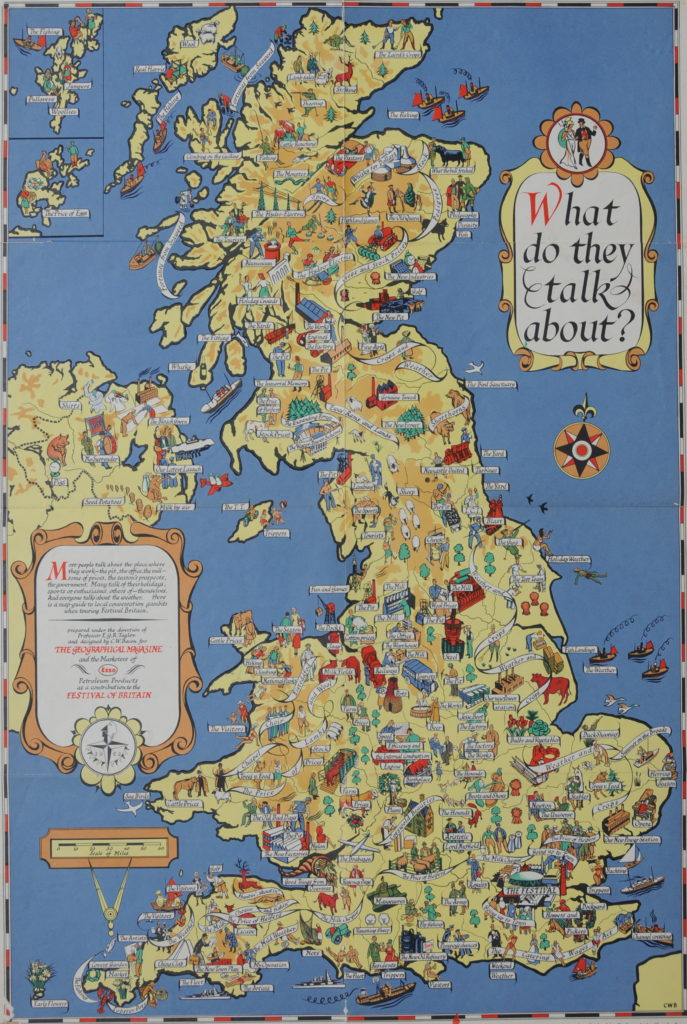

The Festival Of Britain – Maps, Football, Guidebooks. Science And Abram Games

Then in July I wrote a number of posts on the Festival of Britain, one of which included this fantastic map published to illustrate the “local conversational gambits when touring the country”.

Comments gave personal experiences of the Festival, including from Patsy:

At the age of 6, I attended the festival of Britain.

I only have snatched of memories of it. Yet it is something I will never completely forget. I remember particularly the huge ‘pole’ rising into the sky – the Skylon – I couldn’t understand what it was for. There were squirrels in the trees – models of squirrels – I wondered why they didn’t have real squirrels.

I remember being bewildered by the crowds and I remember an overhead cable car. Other than that, memory fades.

And from Veronica:

I went to the Festival of Britain and it was a memorable experience for someone especially who had lived through the war years , as well as going to the Festival itself we saw much of London still showing all the dreadful damage still awaiting re-development. As well as that we got to go into the Dome of Discovery and saw the actual “largest piece of Plate Glass ever made at that time” My father worked on that and Pilkington Brother Glass manufacturers of St Helens, Lancashire had to have a special “low-loader vehicle” made to bring it down to London. We all lined the streets to see it go on its way.

And from Geraldine Terry:

My father was a joiner from Tyneside who traveled to London and found work on the Royal Festival Hall construction site. He helped to make some of the concrete shuttering. He returned to Tyneside after the Festival of Britain, but it was an important period in his life. He told me that the construction workers were given free tickets to the inaugural concert, which he enjoyed.

I am researching my father’s life and would love to know more about what it was like to be involved in building the Hall. If anyone knows of any workers’ accounts, I’d appreciate hearing about them.

Unfortunately I have not found any accounts from those who worked on building the Royal Festival Hall and the Festival in general – they would be fascinating to read.

Canterbury – 1948 and 2016

As well as London, my father also took lots of photos across the country whilst during National Service and on cycling holidays across the Youth Hostels of the country. In August I visited a number of these locations across England and Scotland. One was Canterbury in Kent and this is one of the photos my father took.

Both Annie and Geraldine directed me to the 1944 film A Canterbury Tale which can be viewed online here. A really good film, but obviously of the period and the end of the film includes a number of shots in and around Canterbury showing how badly the city was bombed. One scene includes the following clip taken from almost exactly the same position as the photo my father took.

The Furthest Object Visible From The Shard

In September I spent a day climbing five of the highest locations in London starting with one of the earliest (The Monument) to the latest (Shard). From the Shard I wondered what was the furthest object I could see from the top (see the ghostly image of a chimney on the horizon towards the right of the following photo)

There are loads of good viewpoints in and around London and Pimlico Pete mentioned one which is on my list for this year:

Barnet church tower is open on Saturdays in July and August. It’s well worth the climb up the claustrophobic stairwell because the views are outstanding. I have clocked Wrotham transmitter mast at 31 miles and St John’s church tower in Higham at 32.4 so not quite matching the feat we see here. I found it useful to manipulate the contrast and colour tint in Photoshop to bring out the fuzzy detail. Wrotham would have remained unspotted otherwise.

I also had some interesting comments on the blog and via Twitter correctly advising that actually the Sun, or perhaps even the Andromeda Nebula would be the furthest things that could be seen, so perhaps I need to correct the title to terrestrial objects, and with the level of light pollution in London I suspect you could never see the later.

St. Pancras Old Church, Purchese Street, Gas And Coal Works

in October I went to the area around St. Pancras Old Church to find the location from where this and a couple of other photos were taken. The church is in the background on the right behind the trees.

The area was home to a number of coal storage depots, from where coal would be collected for onward distribution across London. Some comments on how this worked, and how dangerous this could be. Firstly from Keith:

Howdy! The Purchese Street depot was built in 1898 by the Midland Railway. The depot took the form of drops – the coal fell from a wagon on the high level directly into dealers’ wagons avoiding the time and expense of transhipment but generating noise and dust. Last time I was up that way there was a rather nice red brick retaining wall. There was a flying bomb dropped around here and maybe that is why the place looks rather messy. 1940-41 damage was usually tidied up more neatly than that.

From Denis:

Coal was held in a hopper, and the coal merchant would park the lorry underneath and hold an empty sack under the hopper outlet, press a pedal to open the hopper, allowing coal to fall into the sack, which was then stacked on the back of the lorry where they stood. Made loading a bit easier. My dad used this yard a lot. One day a fellow coalman had a seizure/fit whilst filling a sack and was just rooted to the spot with his foot on the pedal as coal fell all over him. The other coalmen fortunately were on hand to save him. I was just a kid and was there with my dad that day, I’ll never forget it.

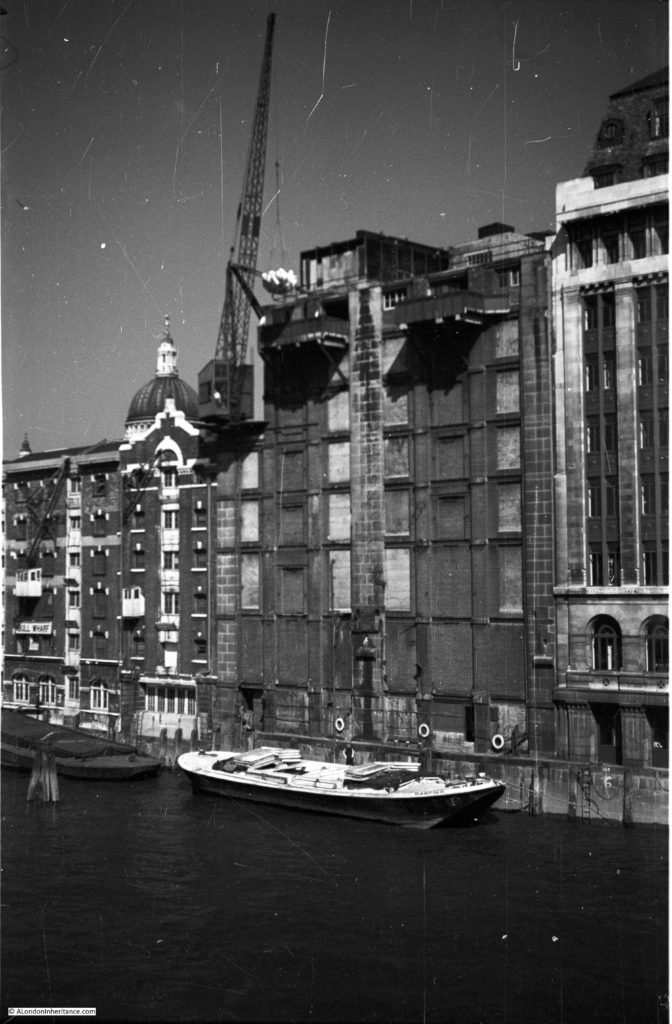

Warehouses And Barges In The Heart Of The City

Also in October I published some of my father’s photos of when the warehouses were still working in central London:

Thanks to Jerry who pointed out that I had got my captions round the wrong way (probably as a result of late Saturday night writing) and also recalling the terrible working conditions of those working in the streets along the river:

Pickle Herring Street ( where incidentally there were a number of fish stalls) is the image that you’ve associated with the large ship actually shown in the neighbouring photograph, swap the captions and you’ve done it. My own father who was born in 1924 actually grew up around the Shad Thames an Pickle Herring Street area, playing amongst the barges along the Thames, an activity made famous by the 1950 Film The Mudlarks. His mother apparently worked on the family fish stall on Pickle Herring Street, as mentioned above and not surprisingly contracted severe arthritis in her hands, working in such freezing conditions in the winter here, must have been dreadful. I recall walking around Shad Thames in the 1980’s before major redevelopment and restoration and finding abandoned Wharehouses still with the produce they handled pouring out of rotten doorways, this included flour that probably would have been used by the nearby Peek Freans and Jacobs biscuits factories.

I was also sent some wonderful photos from David Smith. His mother had taken them in the 1960s including this photo looking up the Thames from Tower Bridge.

The Lord Mayor’s Show In The Early 1980s

In November it was the turn for some of my photos from the 1980s, this time photos from the Lord Mayor’s Show,

It was really good that someone saw the post and also themselves in one of the photos – from Julie:

Every year, my kids have to endure, as we watch the Lord Mayor s parade on TV, my trip down memory lane recounting the year Tom ( husband) and I took part, alongside many of our fellow Disney workers in this wonderful parade

I couldn’t believe it when, upon opening your blog, daring to hope that we might have been snapped…….. there we are! Me ( Cinderella) and other half Tom, (Bert) ……

I remember, it rained that day too, as it so often does for the parade!

But nobody minded… Long live the parade!

The photos also showed the high level walkways that were once a feature along London Wall. For some more information on these MikeH wrote:

The walkways above street level, which can be seen in the views of London Wall, are all part of the ‘Pedway’ scheme for The City of London in the 1950’s and 60’s. It was planned to separate pedestrians from the road traffic and provide a continuous walkway from building to building and across roads, all new buildings were required to provide this and as adjacent sites were developed the pedway would gradually expand to cover the whole of the city. Many buildings had included this and quite a few bridges were built but inevitably there were many dead ends awaiting further development and the whole plan was abandoned by the 1980’s.

MikeH then provides the link for a film about the walkways:

Further to my previous reply this documentary contains lots of old film including the bomb sites around St Pauls. Its called Elevating London by Chris Bevan Lee. http://vimeo.com/80787092

The film is a brilliant account of the rebuilding of this part of London and the Pedway scheme as the walkways were called. I highly recommend watching the film.

The Tiger Tavern At Tower Hill

Also in November I wrote about the Tiger Tavern pub that was once on Tower Hill.

There were rumours about an underground tunnel linking the pub and the Tower of London although I could find no evidence, however Barbara wrote:

You mention a blocked off tunnel in the basement of The Tiger, I have been in that tunnel and also seen the mummified cat, I spent many hours there as my uncle was once the manager.

It would be really interesting to know if any of the tunnel remains under Tower Hill.

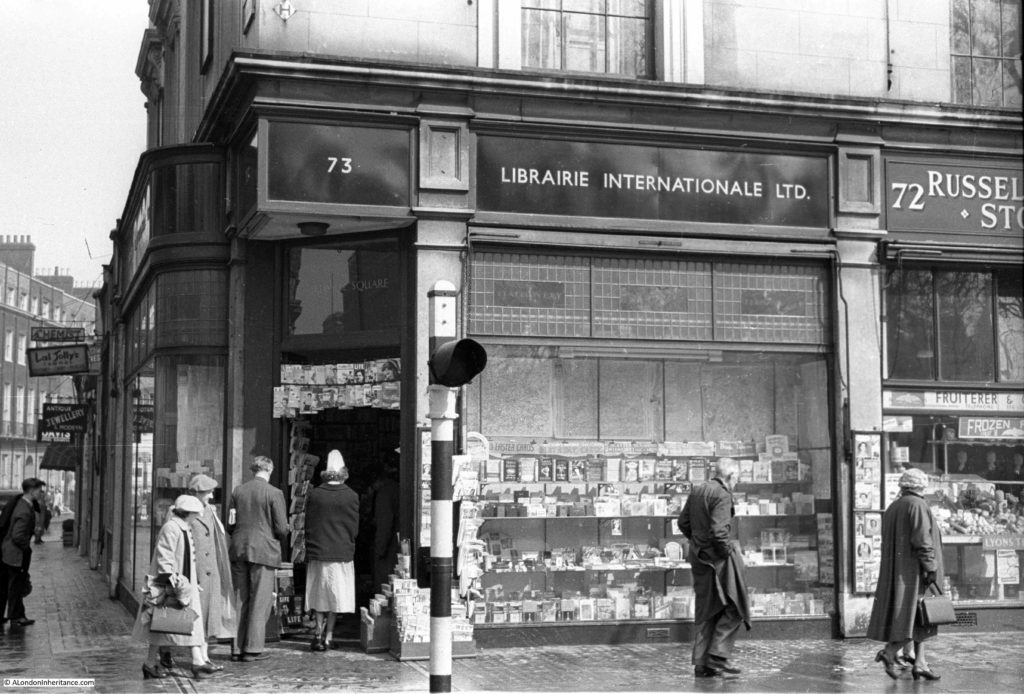

Russell Square And Librairie Internationale

In January I wrote about the Libraire Internationale in Russell Square.

I found evidence of anarchist magazines being sold at the Librairie Internationale, however they seemed very polite anarchists as also found by Rob:

The Times of 1/2/1935 reported on a case in which Gladys Marie, the Duchess of Marlborough, claimed damages from a number of defendants for circulating a libel. “Mr Theobald Matthew, for Librairie Internationale [of Russell Square, W.C.], said that his clients expressed their regret as soon as the libel was brought to their attention and they now offered a sincere and unqualified apology to the Duchess.” Polite radicals indeed!

Then some more information from the excellent London Remembers site

Thanks for publishing the photos of the ‘Turkish Baths’ corner. We’d already stretched our definition of a ‘memorial’ and published that sign on our website. But your photos prompted us to do some more research, trying to understand the history of the site and to find out exactly where the Baths and the Arcade were. With the info from your photos and some maps we’ve got a bit closer: https://www.londonremembers.com/memorials/turkish-baths-in-russell-square

And from Peter:

My eye was taken by the Imperial Hotel. The magnificent edifice dating from the early 20th century was itself a replacement of a previous incarnation. My 4x great-uncle, George Heald, wrote a letter from the Imperial Hotel in 1846 to George Mould in the Railway Office, Carlisle concerning the costings of the new railway that Heald was being asked to engineer between Skipton and Lancaster. Heald travelled the length and breadth of the country and stayed in the best hotels as might be expected for such a prominent engineer. His story is on Wikipedia. Mould was another pioneer of railways who lived longer than Heald (1816-1858) and built some of the main railways in Spain

And that was just a small sample of the fascinating and informative comments I received over the last year. Again my thanks for every single comment, all the feedback and additional information. And now to start next week’s post.