After the large amount of text in yesterday’s post, it is time for a photographic walk around the Festival of Britain on the South Bank.

My father took only a small number of photos of the Festival of Britain – I do not know why when he took so many of the site before it was cleared. Perhaps what is about to be lost is more interesting than what is here now – the mundane everyday. I am always conscious of this with my own photography that what is ordinary today will be lost at some point in the future and will then be the interesting past.

To understand the site, I have therefore been collecting any postcards I could find over the last few years and it is these I will use to take a guided walk around the South Bank Festival of Britain.

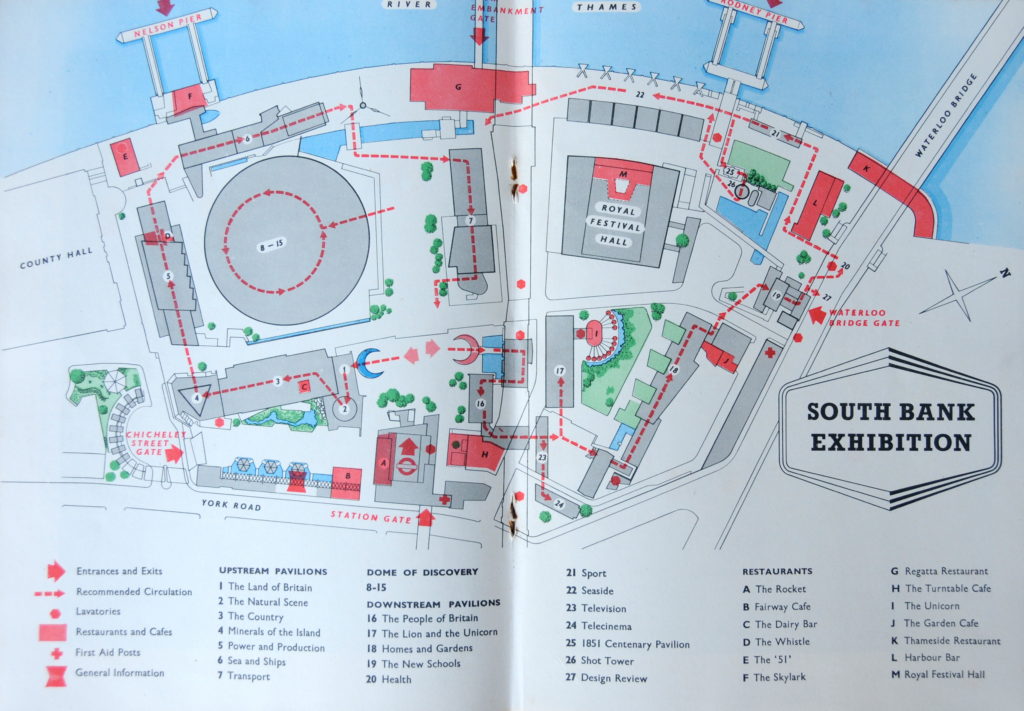

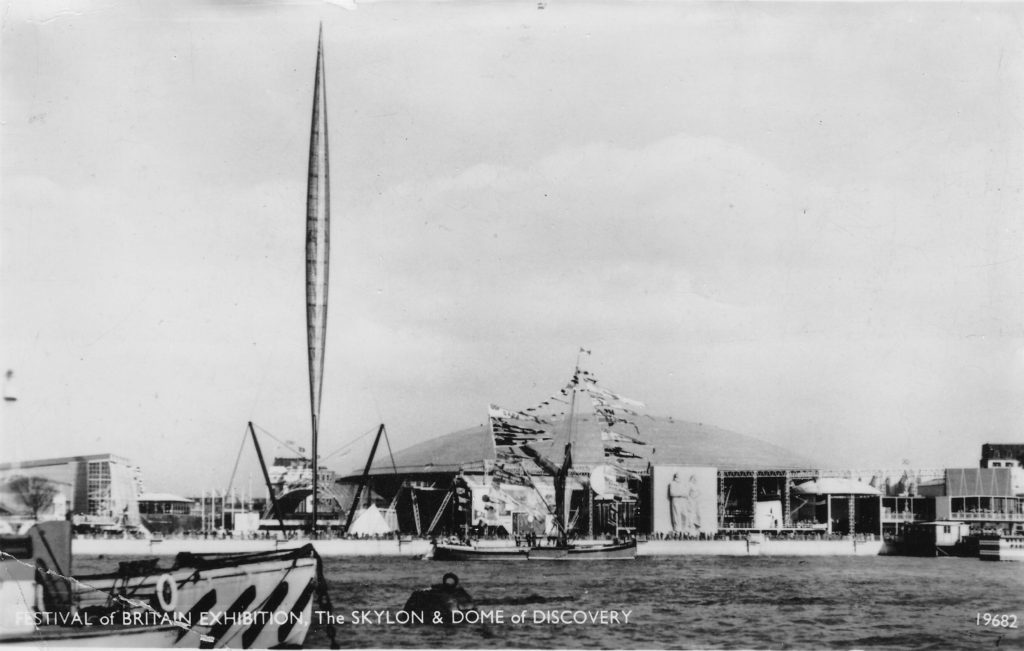

The South Bank site was divided into a number of pavilions, exhibitions, restaurants and cafes with two large buildings, the Dome of Discovery and the Festival Hall. Sculpture and artwork was also distributed across the site along with the Skylon, probably the most famous landmark at the festival.

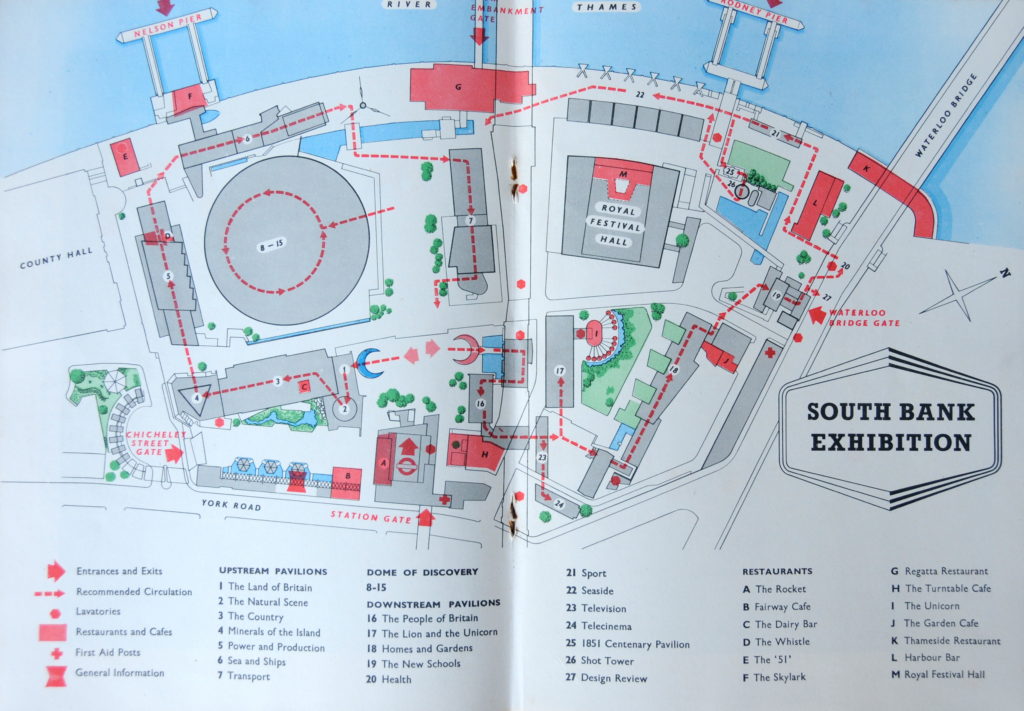

The site was set-up with a recommended walk that would take the visitor through a structured story of the British family, British achievements and how these achievements would provide a better future.

The Hungerford Railway Bridge almost divided the South Bank area in half and split the festival into an Upstream Circuit – The Land and a Downstream Circuit – The People.

In today’s post we will walk round the Upstream Circuit – The Land and in my next post cover the Downstream Circuit.

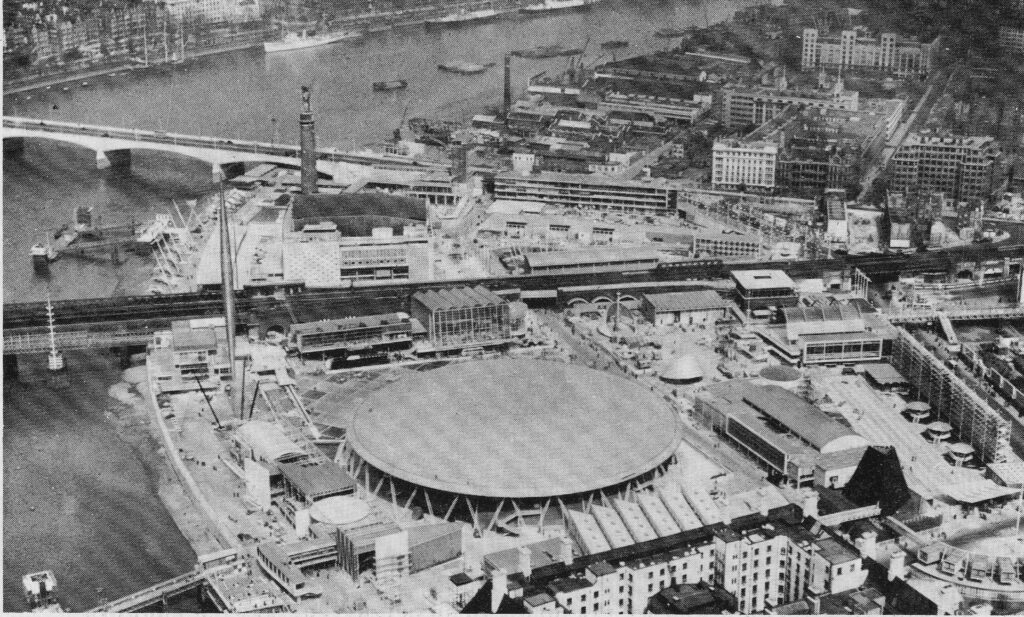

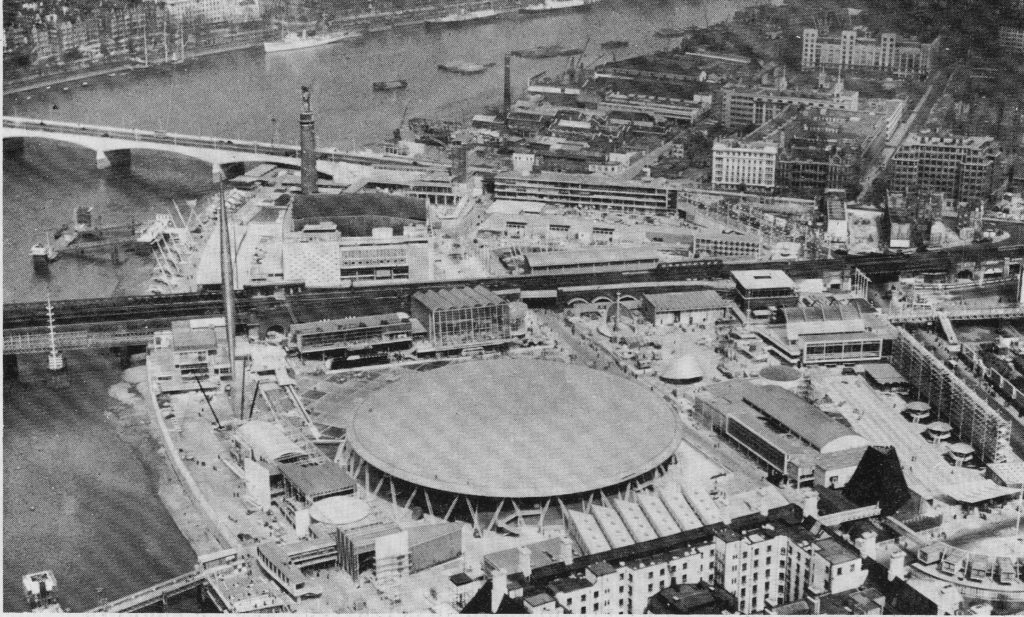

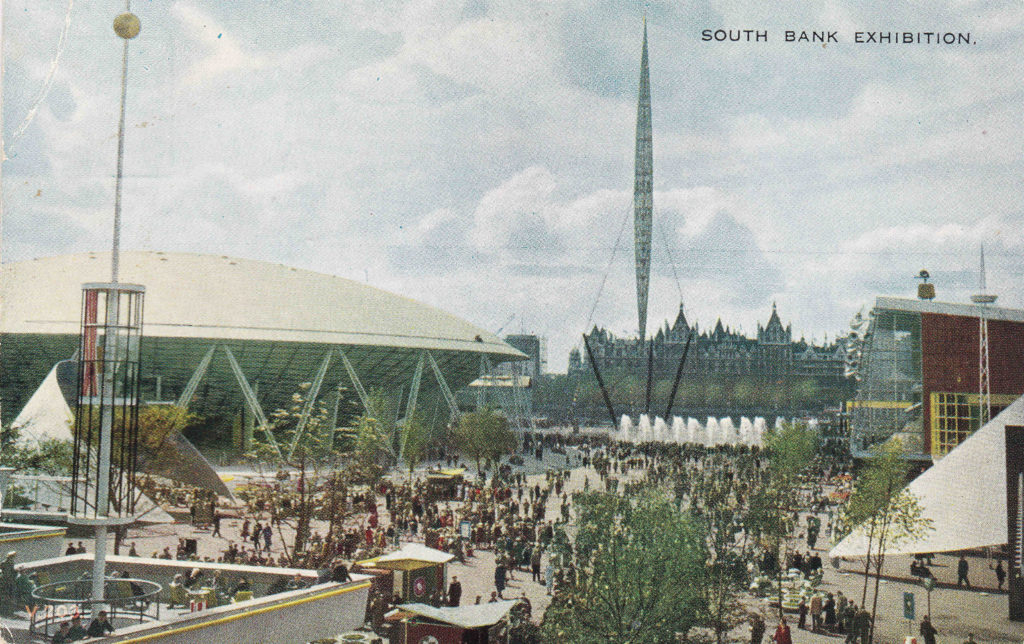

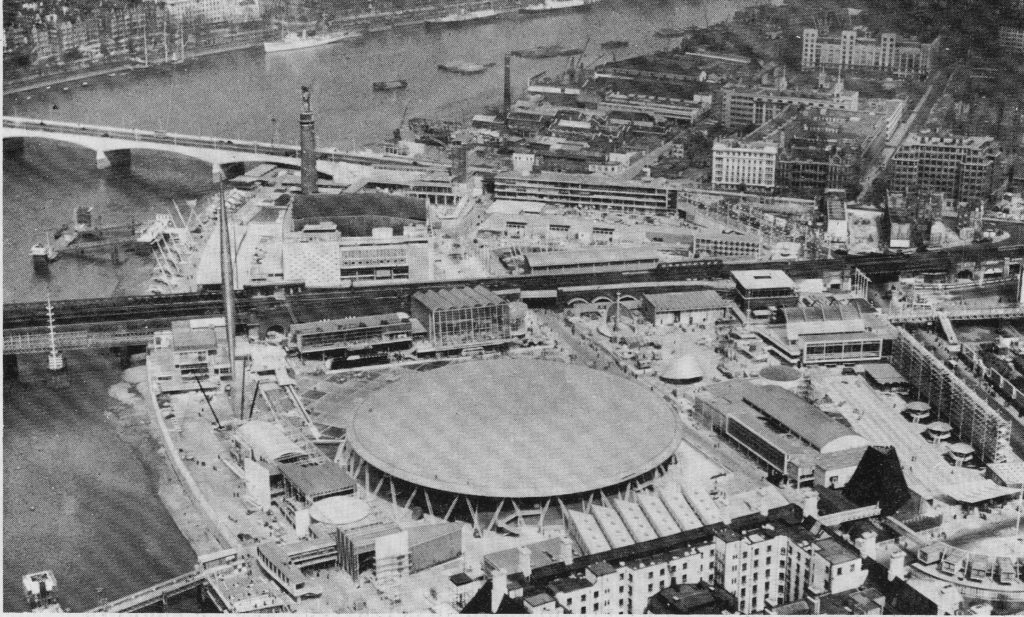

The following photo shows the overall South Bank site looking downstream. County Hall is at the bottom of the photo with Waterloo Bridge forming the boundary to the site at the top. The photo shows the size of the Dome of Discovery. To the left of the Dome is the Skylon and above both is Hungerford Rail Bridge. The upstream circuit is the area bounded by County Hall and Hungerford Bridge. To the right of the Dome, Belvedere Road can be seen dividing the upstream circuit. In the middle right is the bridge across York Road leading to the Station Gate and it is through here that we will be entering the Festival.

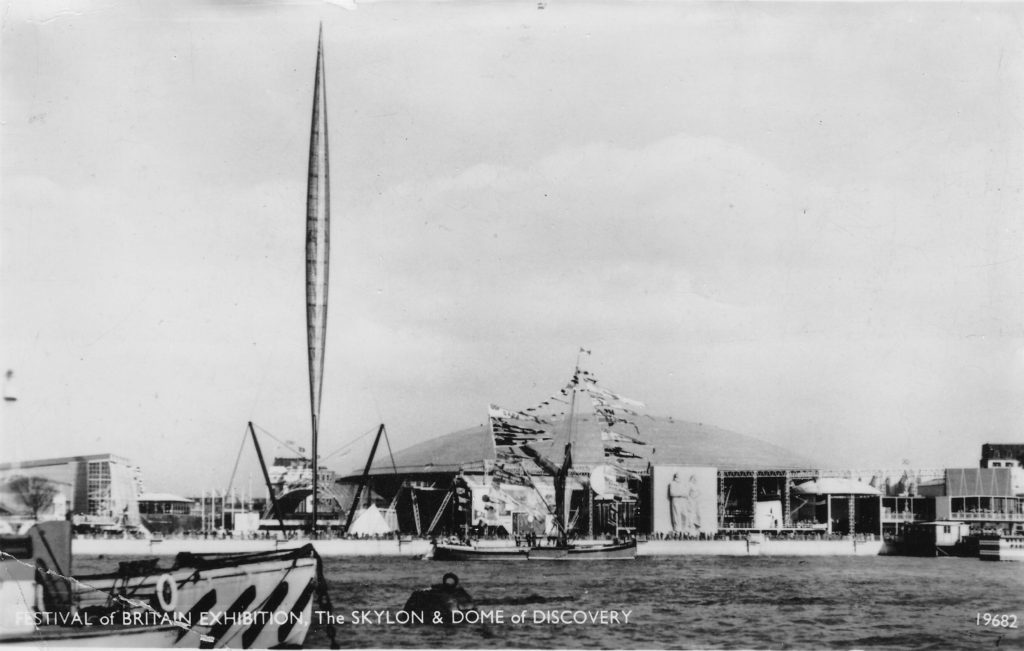

Firstly, a couple of views from across the river which give a good impression of the height of the Skylon. Just to the centre right of the photo is one of the large works of sculpture created for the Festival. This was “The Islanders” by the Austrian-British sculptor Siegfried Charoux. It was displayed by the Sea and Ships pavilion and was of two adults and a child and symbolised the relationship between the British people and the sea.

In the above photo there is a large sculpture just to the right of centre in front of the Dome. This is The Islanders by Siegfried Charoux. The large stone relief was intended to portray the struggle and resilience of the British people. The following photo shows The Islanders in detail:

Another photo from the north bank of the river looking towards the Royal Festival Hall and the Shot Tower which again gives a good view of the Skylon.

Now it is time for a walk around the upstream circuit of the Festival.

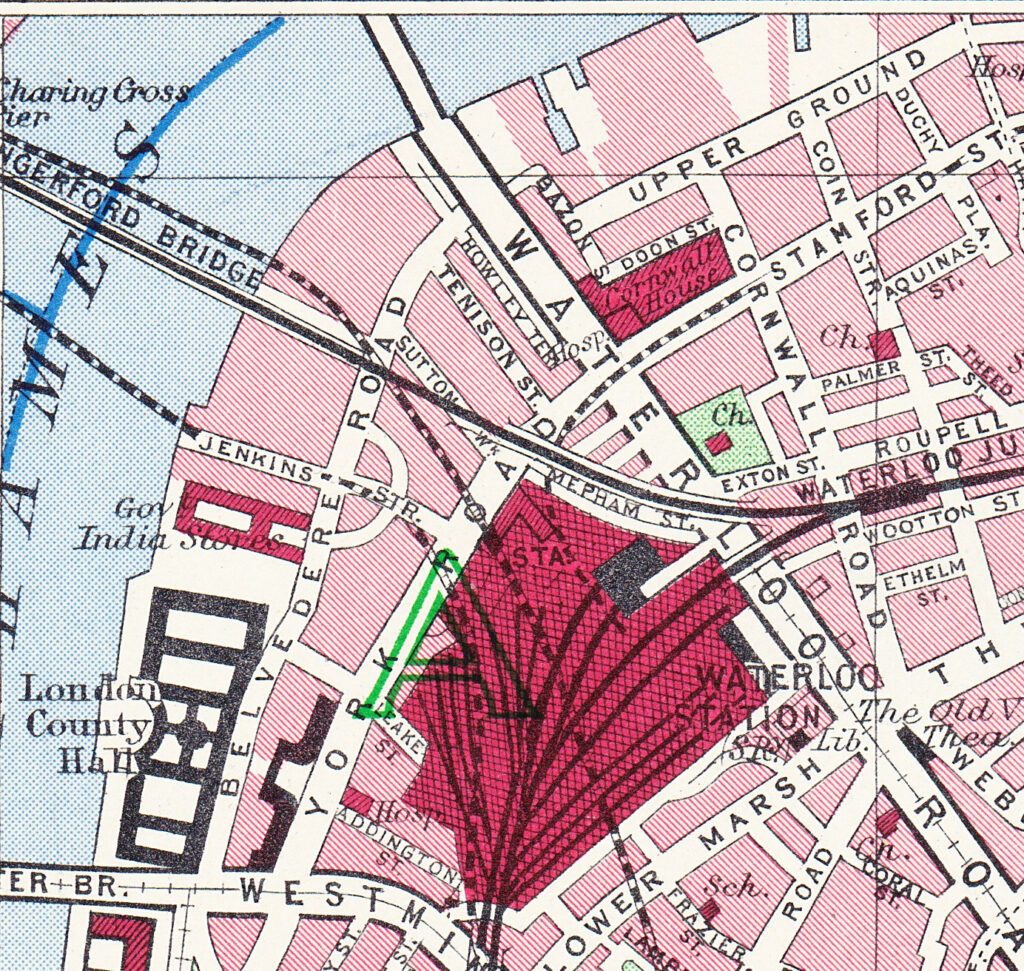

The map below is from the guide-book for the South Bank exhibition. The same landmarks from my last three posts still provide the boundaries – Waterloo Bridge to the right, Hungerford Bridge in the middle and County Hall on the left. The outline of Belvedere Road can also be found in the festival site.

The red dotted line shows the recommended walk around the festival and it is this route we will follow after entering through the Station Gate in York Road.

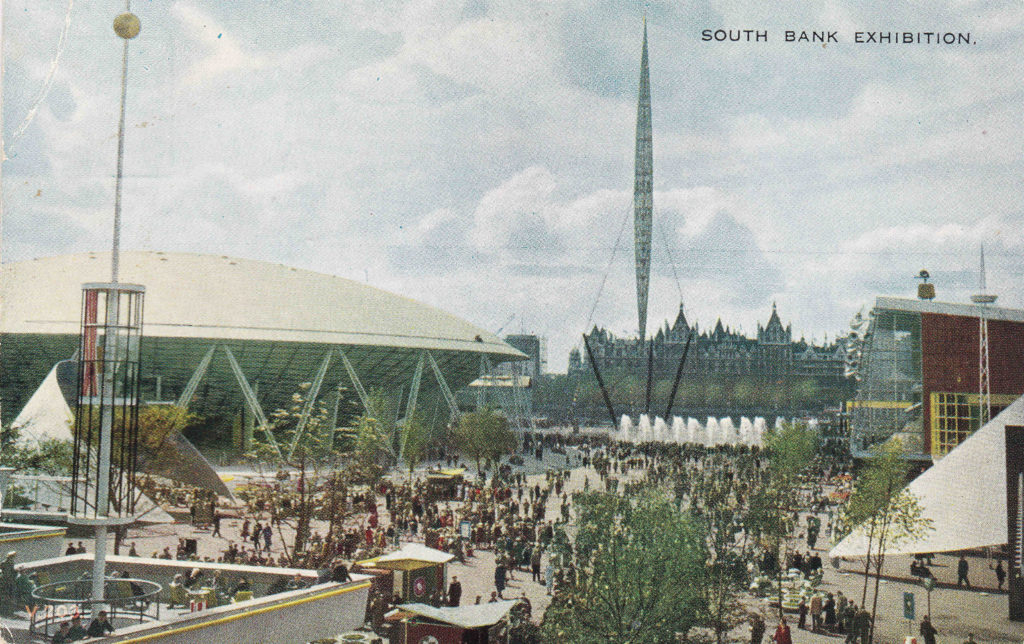

As you walk through the entrance buildings at the Station Gate and through to the open space where there is an unobstructed view across the festival site to the river, the Dome of Discovery to the left and the Skylon dominating view – see the photo below.

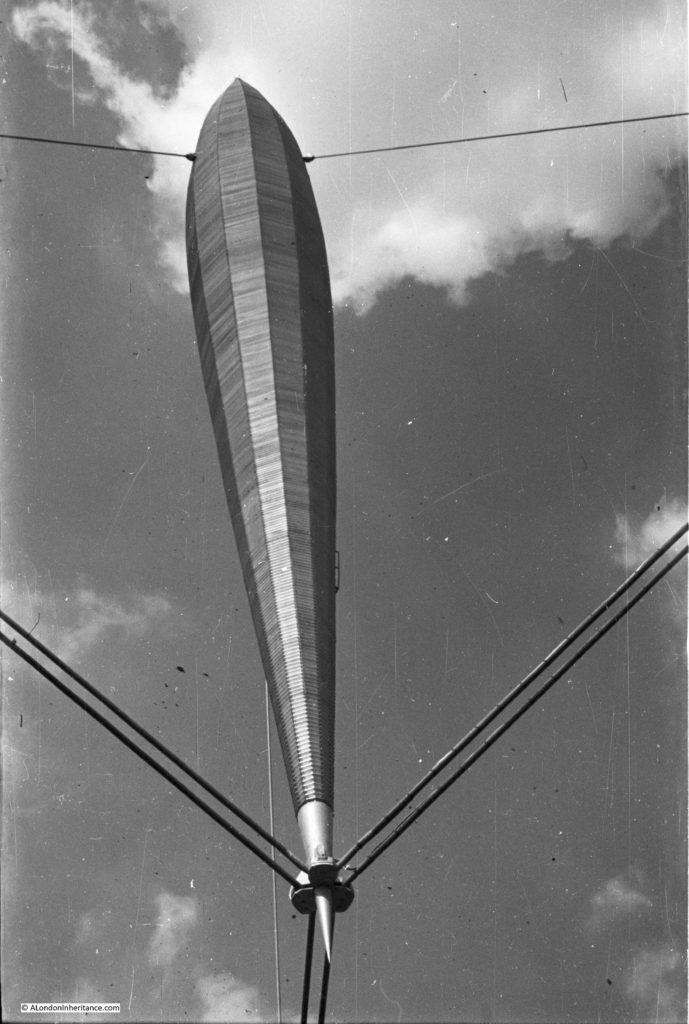

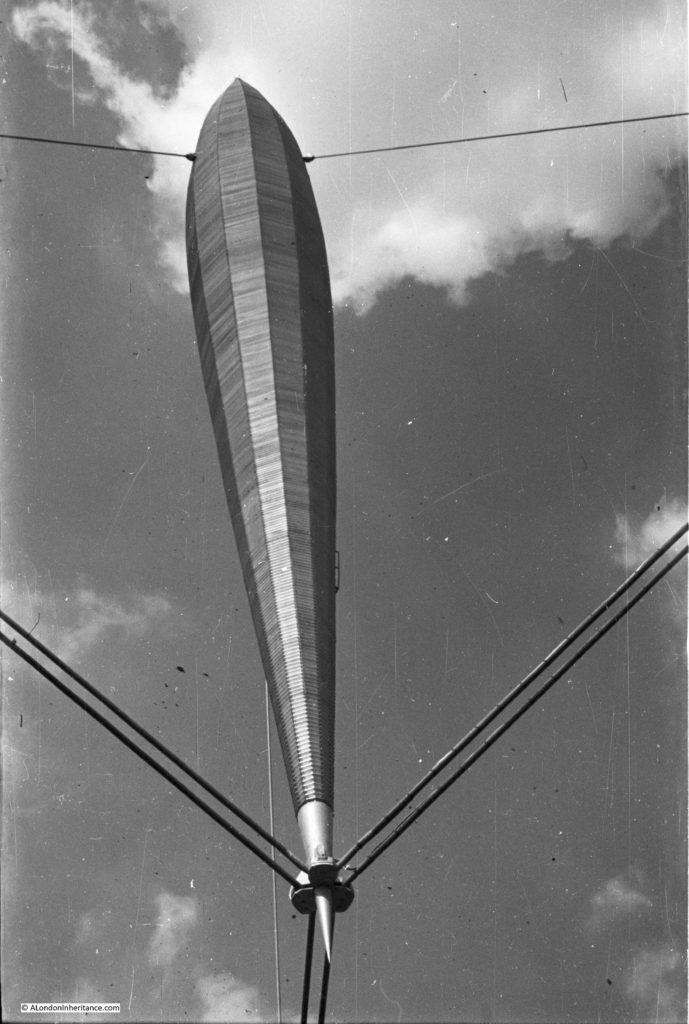

The design for the Skylon was the result of a competition for a “vertical feature” for the festival site. Of 157 entries, the design by Philip Powell and Hidalgo Moya along with the engineer Felix Samuely was chosen.

The main body of the Skylon was 250 feet in height, add in the suspension off the ground and the total height was 300 feet. Three sets of cables held the Skylon in a cradle at the lowest point, and half way up at the thickest point a set of guy wires held the Skylon in a vertical position.

Aluminium louvered panels were installed on the outer edge of the Skylon and lights were installed inside, so during the day, the Skylon would sparkle in sunshine and at night it would be lit from the inside.

The name for the Skylon was also chosen in a competition. The winning entry was from a Mrs Sheppard Fidler and the name was a combination of Sky and the end of Nylon (the latest modern invention), which when combined gave the futuristic sounding name of Skylon.

The rumour and joke at the time of the Festival was that the Skylon was like the British economy in that it had no visible means of support.

The above view was taken from where Shell Centre now stands, I took the following from the edge of Belvedere Road, roughly to the left of where the hut is shown in the above photo, looking towards the position of the Skylon.

A colour photo of roughly the same area which was probably taken from the roof of the York Road entrance building.

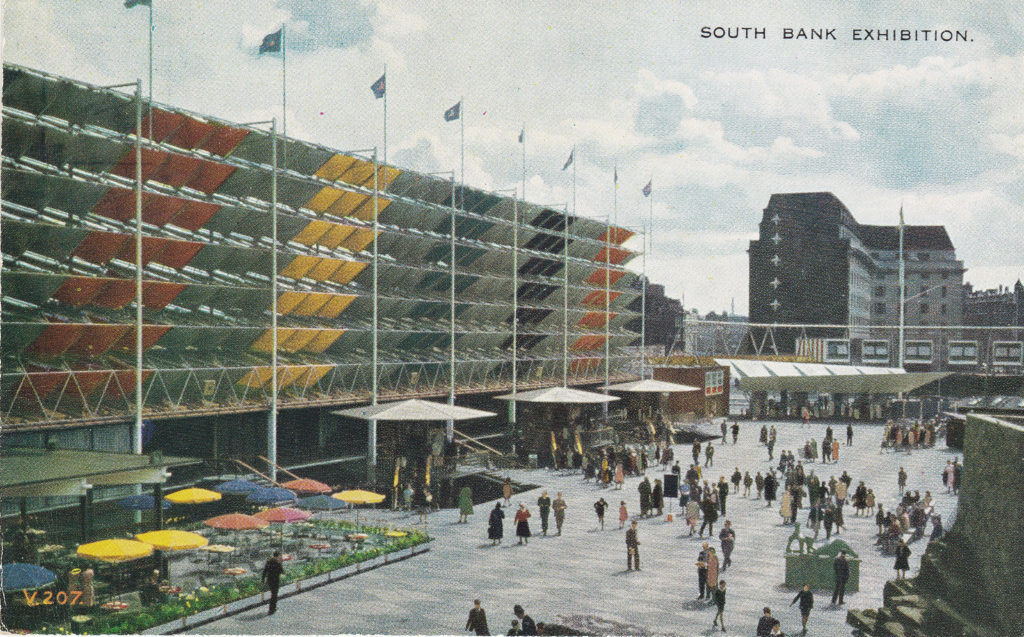

Rather than walk down to the Skylon we will follow the route round the Festival as shown in the map, but before entering the first pavilion, turn left and head towards building B on the map, the Fairway Cafe. The following photo is looking towards County Hall with the Fairway Cafe on the lower left on the photo. The screen on the left was to screen the Festival site from York Road.

Colour was key to the design of all aspects of the Festival and as well as the use of colour on the large screen the cafe was also brightly coloured including the use of different coloured parasols. After the long years of war, rationing and austerity, the Festival was a new use of colour in a grey world.

Also from this location, we can look to the right and see the Royal Festival Hall and Shot Tower on the other side of Hungerford Bridge with the large Transport Pavilion to the left of center.

To return to the route around the Festival, enter the first pavilion, number 1 on the map “The Land of Britain”. This pavilion explained that the “land is the beginning of the story and it is the land that gives the story its continuity” and explained that the land of Great Britain has been millions of years in the making and has created riches available for the use of the people. Ancient muds have formed Welsh Slate, swamps have produced rich coal seams and the salts from stagnant seas have produced fertilisers.

The next pavilion is number 2, “The Natural Scene” and tells the story of the British landscape showing examples from across the country, the fresh waters of the Lake District, the chalk hills of the North Downs which are so “typically British”, birds, trees and grasses of the country.

Next along is pavilion 3, “The Country”. This pavilion acknowledges the separation of the British people as either countrymen and townsmen and states that if these two groups are to march in step, it is essential that each should understand the conditions in which the other lives and works (I suspect this separation has grown wider in the years since the Festival rather than marching in step).

The Country pavilion tells the story of farming a varied landscape, how science has been applied to modern agriculture, livestock and breeding, milk – one of the most valuable of all our raw materials, planning the use of the land and the farmer of today.

The section of the guide covering this pavilion ends with “It is, then, finally, the farmer and his family that we owe the prosperity and permanence of our countryside”.

An internal view of The Country pavilion showing the latest agricultural machinery.

Now walk through pavilion 4, the Minerals of the Land which shows how Coal and Coal by products have been used, the use of iron and the history of steel making along with the abundance of other minerals in the land of Great Britain.

Walk out of pavilion 4 and look back towards Hungerford Bridge and this is the view. The pavilions we have just walked through are on the right. The walkway on the right is Belvedere Road and if you follow this walkway in the distance you can see the bridge through Hungerford Bridge that is still there today and I featured during the post on the walk along Belvedere Road.

The following photo is roughly from the same position today, I should have been slightly forward and to the left, however the coaches then obscured the view of the bridge under Hungerford Bridge which you can see as the blue bridge at the end of Belvedere Road.

On the right is Shell Centre, during the Festival of Britain it was The Country pavilion and before the Festival, the site had the row of buildings which included the County Cafe as in the photo in my walk along Belvedere Road. Three phases in the history of this site.

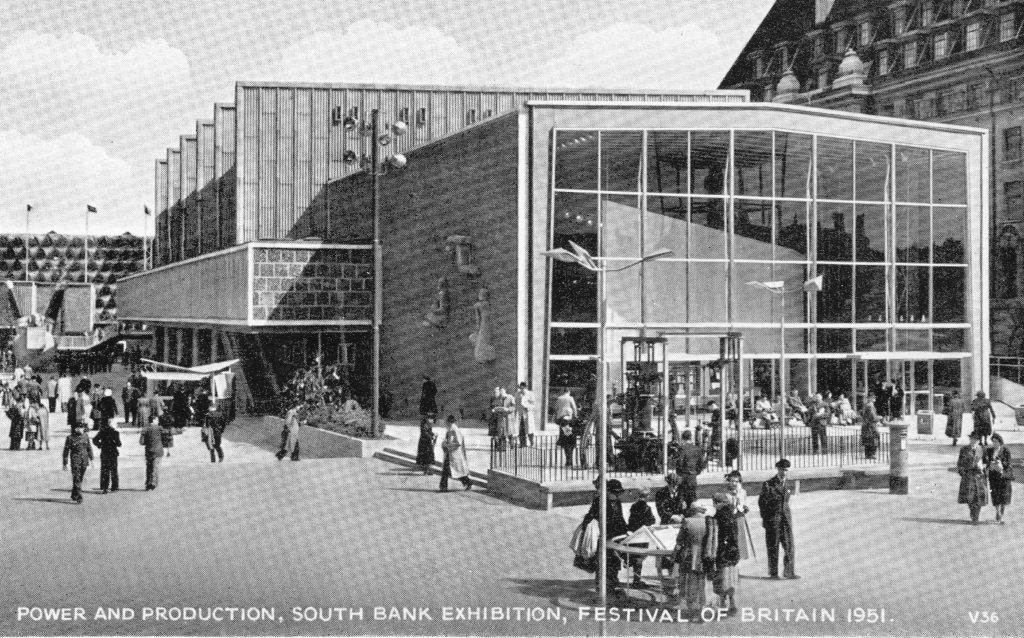

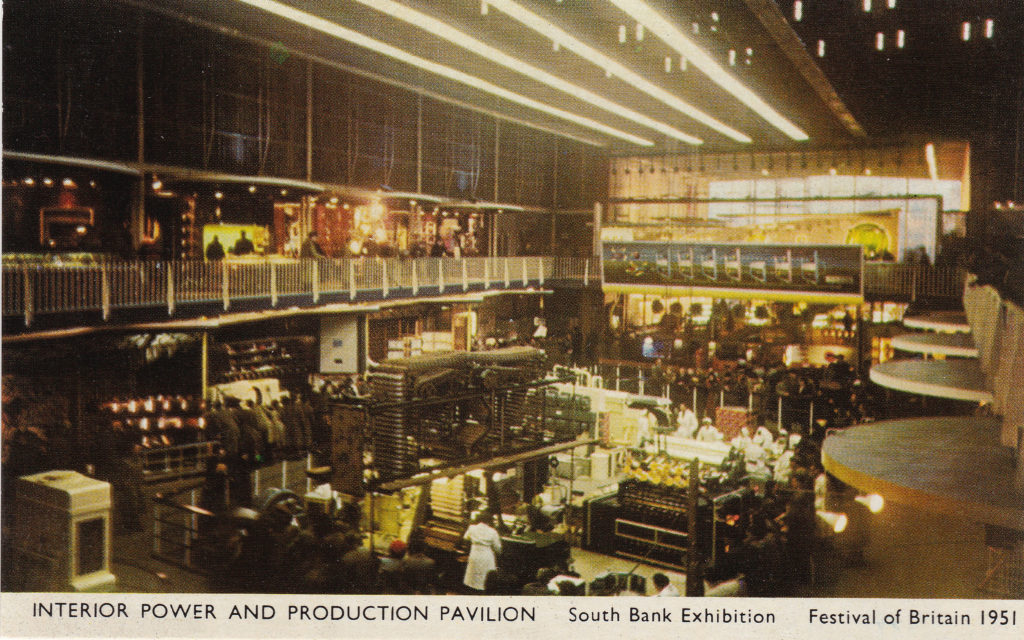

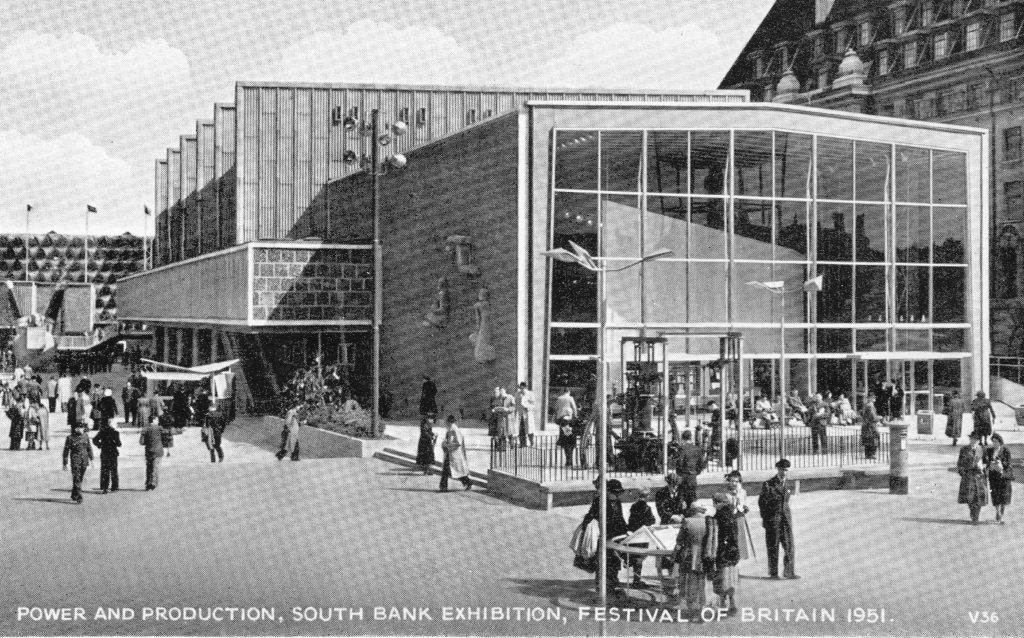

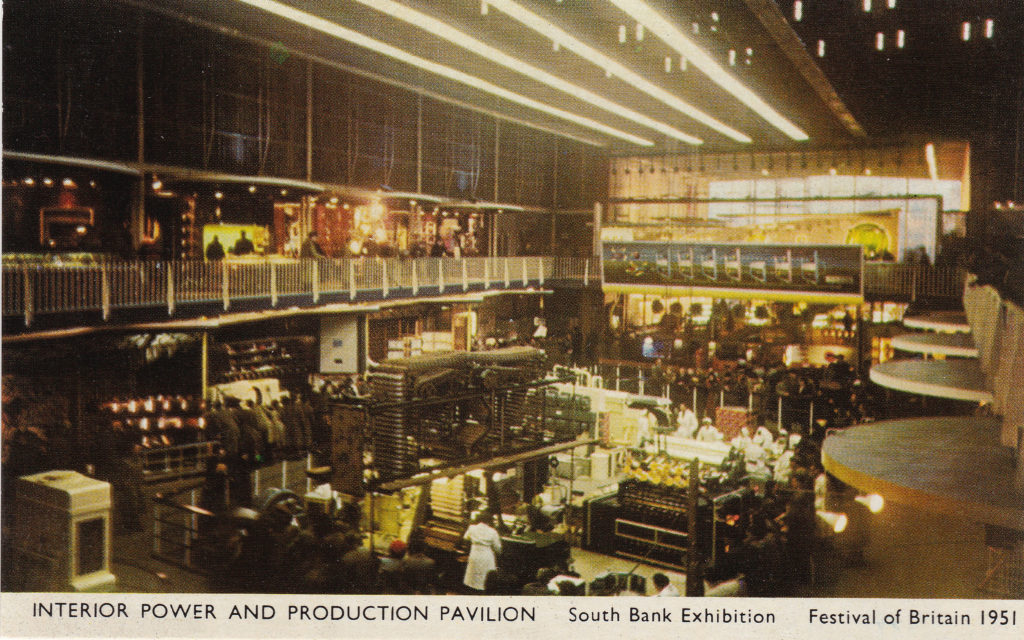

Now lets walk into Pavilion 5, Power and Production. This large pavilion tells the story of how power has been harnessed in the services of industry and how raw materials are used to generate electricity. The pavilion emphasises that everything that is manufactured must first be designed and focuses on six British industries: woodworking, rubber and plastics, textiles, pottery and the story of paper-making and printing.

The following photo shows the Power and Production Pavilion looking from the embankment.

The same view today.

And a view of the interior of the Power and Production Pavilion. The pavilion was not just about the story of how Power and Production has supported British industry, the story also emphasised that craftsmen cannot be replaced by machines and within the pavilion (the people in white coats) there were demonstrations of British craftsmen making silverware, fine instruments, boots and shoes, blowing and cutting glass, hand painting pottery and making paper.

The Festival highlighted that these were British craftsmen and throughout the Festival it was only British goods and products that were on show.

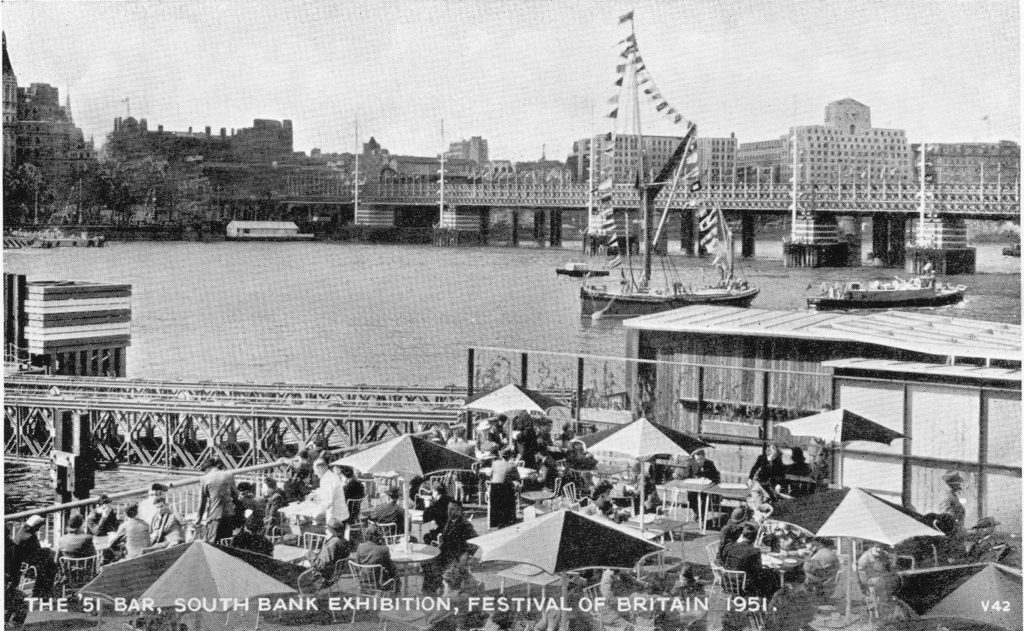

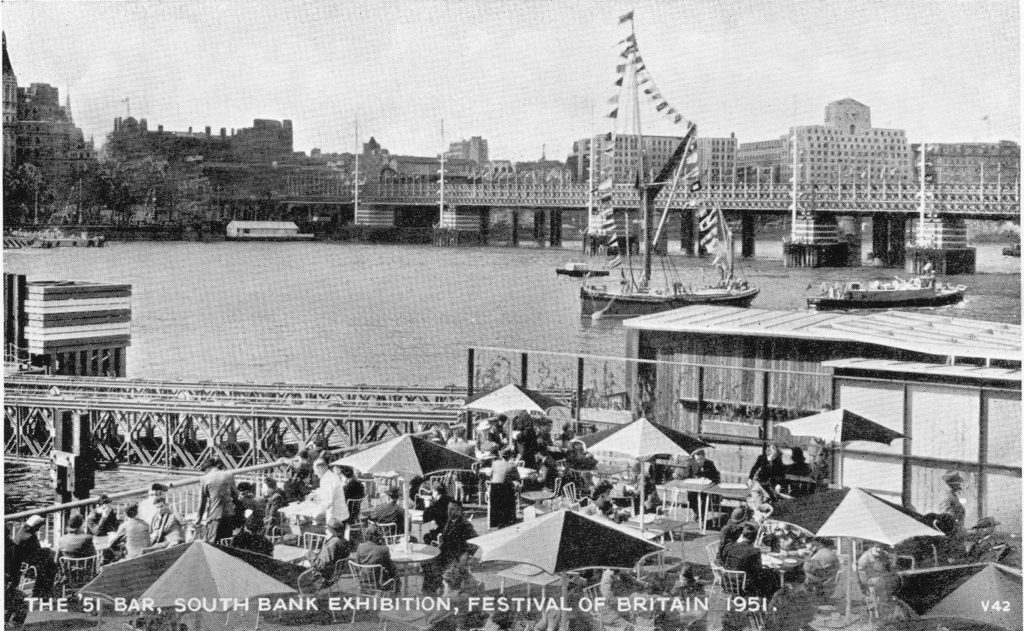

Having left the Power and Production Pavilion, time for a quick drink before continuing, so head to the box marked E on the map which is the “51 Bar”.

Although the photo is black and white, the cafe used coloured parasols and the chairs were the Antelope chairs designed by Earnest Race and used throughout the Festival. The 51 was described as “a luxury bar, with good snacks” and was catered by Messrs Charles Hagenbach & Sons of Wakefield, Yorkshire. As well as the pavilions, each of the cafes had their own architect and designer. For the 51 Bar it was Leonard Manasseh.

The site of the 51 Bar today:

The use of different external contractors for each of the Festival cafes resulted in variable quality, service and food, which in some of the cafes was very basic.

We now head into Pavilion 6, Sea and Ships.

Sea and Ships stated that “Our ancestors came by sea and found here natural havens for their craft. We still live on the sea and by it, using this same coastline as the childbed of our inheritance – the building of ships for the world and for ourselves”.

This was at a time when the country still had a major ship building industry and shipping was important for our exports as well as imports.

The pavilion examined the history of ship building and then moved to modern ship building including propulsion, propellers, how a ship is built and tested.

The pavilion also looked at the other major British industry associated with the sea, the fishing industry and explained that British fishing grounds now stretch from the coast to the farthest grounds of Iceland and the Arctic Circle, There were also hints at the impact of over fishing as the pavilion looked at the growing area of unprofitable water, but also demonstrated how organised scientific research was being applied to the management and distribution of fishing.

After leaving the Sea and Ships Pavilion, we are at the Skylon and can stand directly underneath. This is one of the few photos my father took at the Festival and was taken from the base of the Skylon.

The Skylon was a remarkable structure and its destruction after the festival, with no preservation or storage must, in my view, be one of the most major acts of vandalism on a significant symbol of the combination of art, design and engineering.

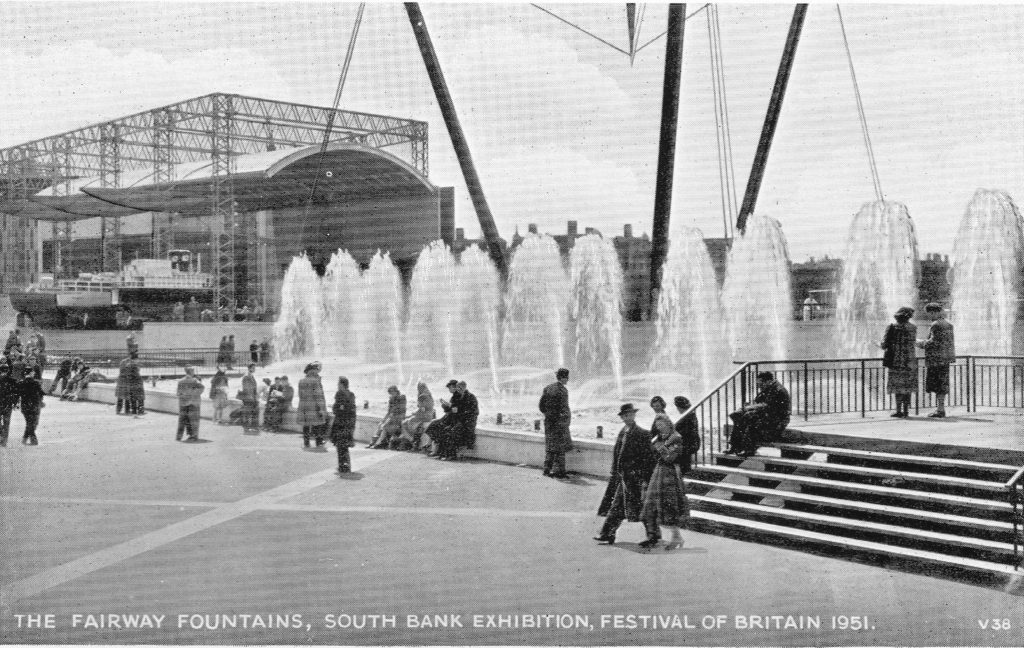

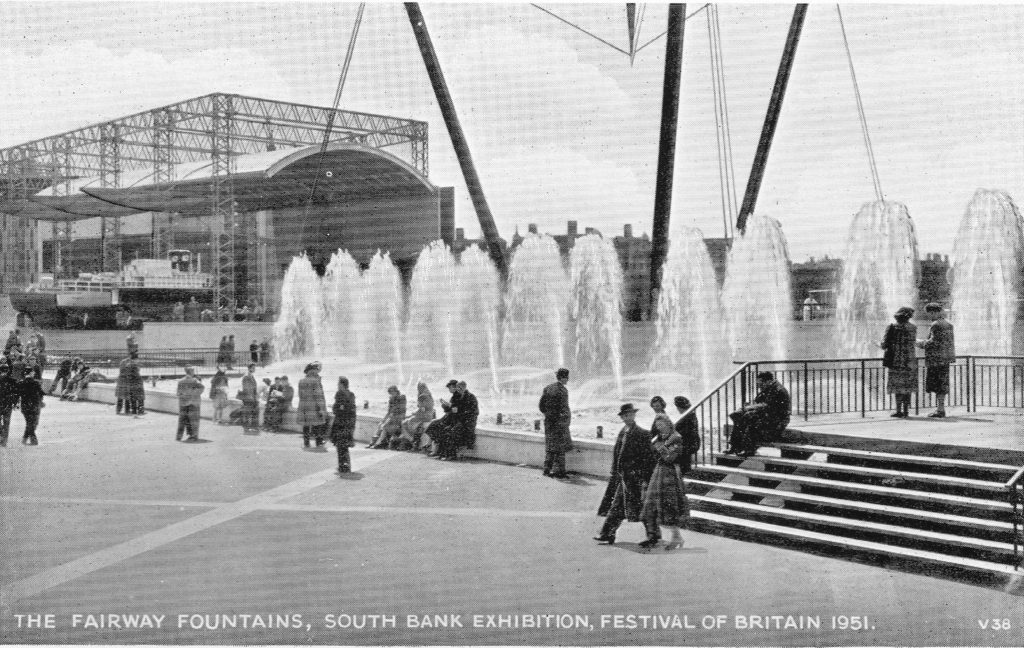

Walk past the Skylon and we can look back at the Sea and Ships Pavilion with the base of the Skylon and the Fairway Fountains in the foreground.

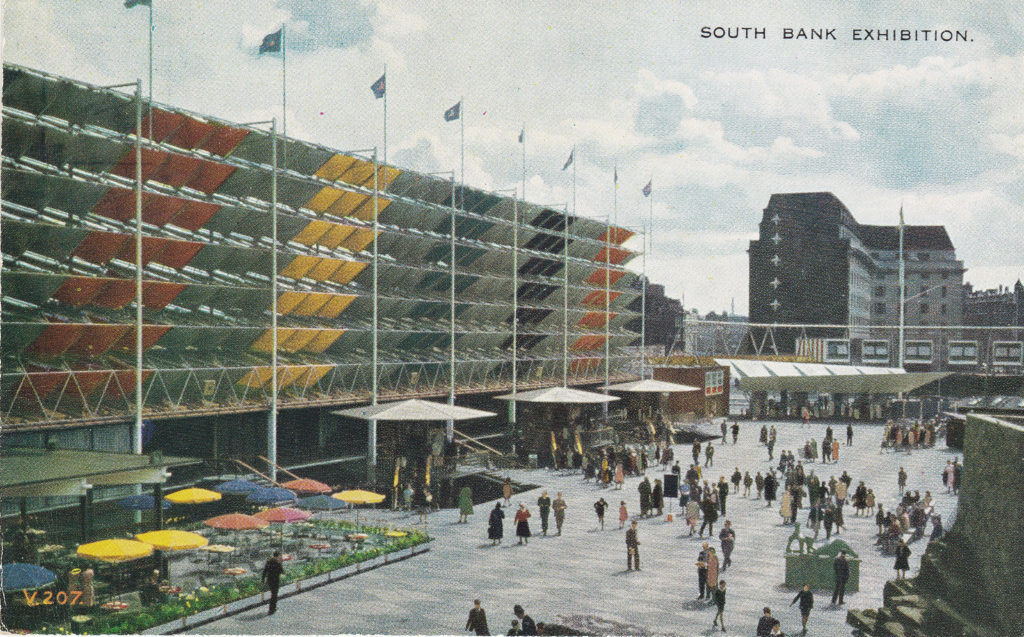

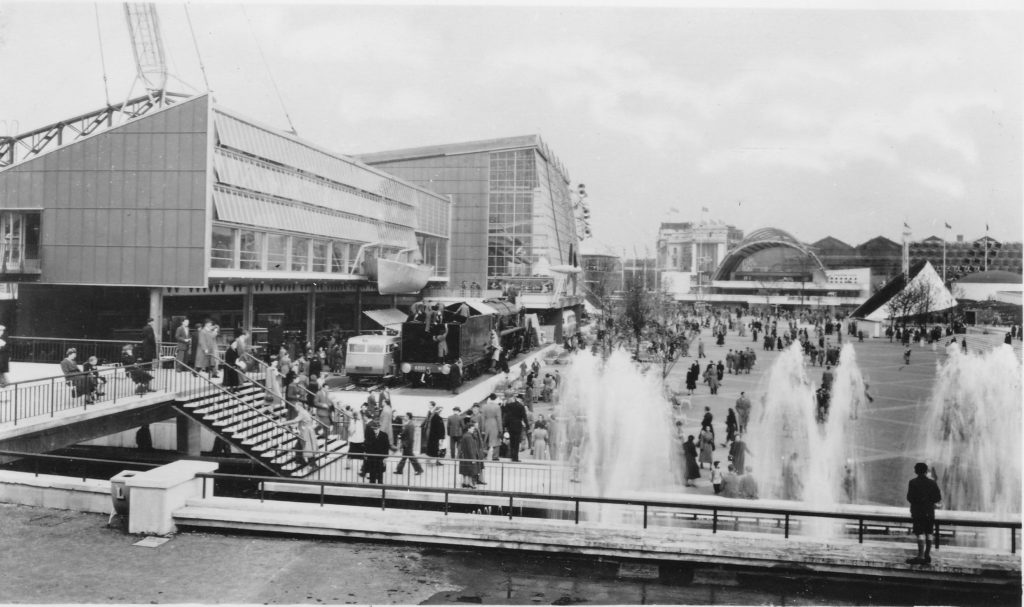

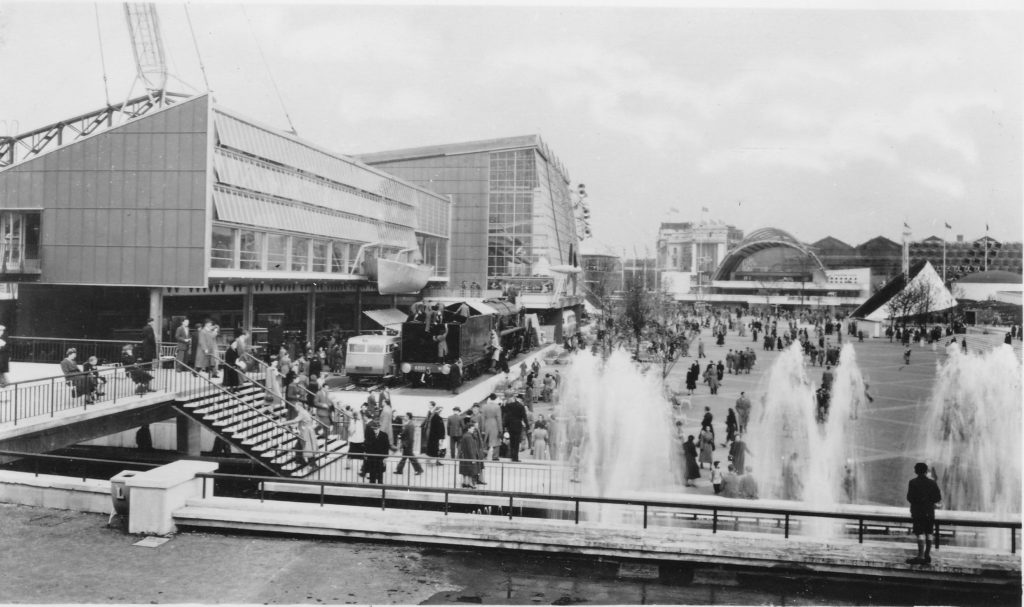

Turning round from the above location, we can look across to the Transport Pavilion. This was a large pavilion that ran along the side of Hungerford Railway Bridge between the embankment and Belvedere Road.

Another view of the Transport Pavilion, the bridge that takes Belvedere Road under Hungerford Bridge is immediately to the right of the large glass building.

Looking down from the embankment towards the Station Entrance. Waterloo Station can be seen in the background.

The train in front of the Transport Pavilion was a 2-8-2 locomotive built-in England for the Indian Government Railways. In the photo above you can see boys climbing over the end of the train.

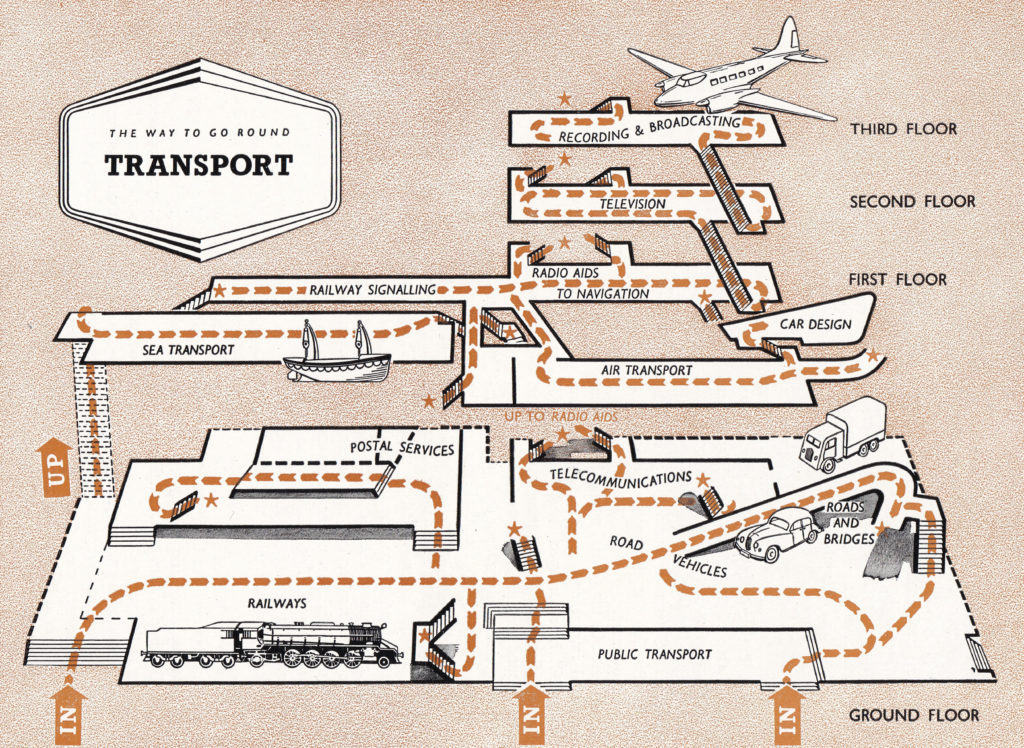

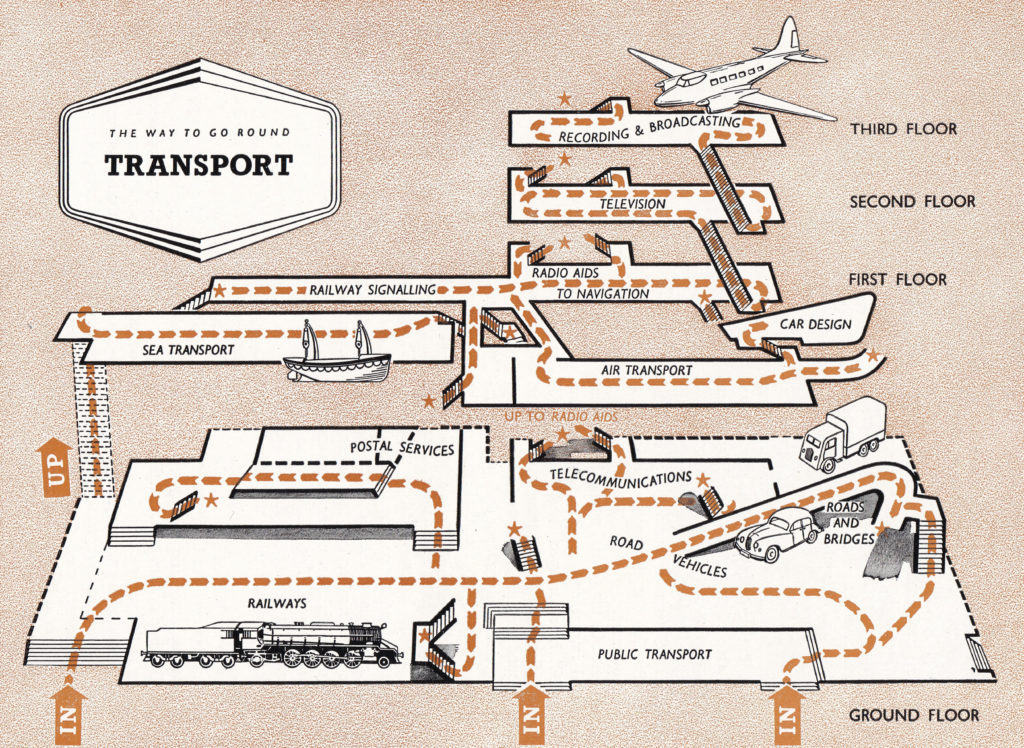

Although it was named the Transport Pavilion, the aim of the Pavilion was to show Communications in general. The plan of the pavilion below shows the recommended walking route.

The Transport Pavilion used examples of British design, engineering and industry to tell the story of how transport had developed and was used in the country.

In Railways, it was stated that Britain gave railways to the world and there were examples of the development of railways in Britain, and within the pavilion was a 600 h.p. diesel-electric locomotive built for the Tasmanian Government and the pavilion also highlighted the transition away from steam. Throughout the Pavilion, it was British innovation that was key, including small details such as “the inventor of the railway ticket was an Englishman named Edmonson. His methods for printing and dating it were the beginnings of the system which has culminated in the coin-operated, ticket-printing, issuing and change giving machine of the present day”.

In the Road Transport section, the breadth and depth of British manufacturing was shown along with facts such as “Britain claims the largest production of bicycles and motorcycles in the world”.

The Air Transport section included a reference to the future Heathrow “the new London Airport still under construction 15 miles west of London. The Terminal Buildings here will be grouped on a 50-acre area in the centre of nine main runways. They house the staff and facilities that enable the airport to handle 4,000 passengers and large quantities of freight every hour of the day or night”.

In Sea Transport the pavilion demonstrated the latest developments in navigation, equipment to support safety at sea along with how the major docks operated including the latest to be completed in Southampton.

The Transport Pavilion also included sections on the latest forms of communications including Radio, Radio Aids to Navigation, Sound Broadcasting and Recording and Television. Again highlighting the latest developments of British science, innovation, design and production.

Another view of the outside of the Transport Pavilion looking towards the river:

And another wider view of the Transport Pavilion looking towards Hungerford Bridge:

The following photo is looking across to the location of the large glass building of the Transport Pavilion.

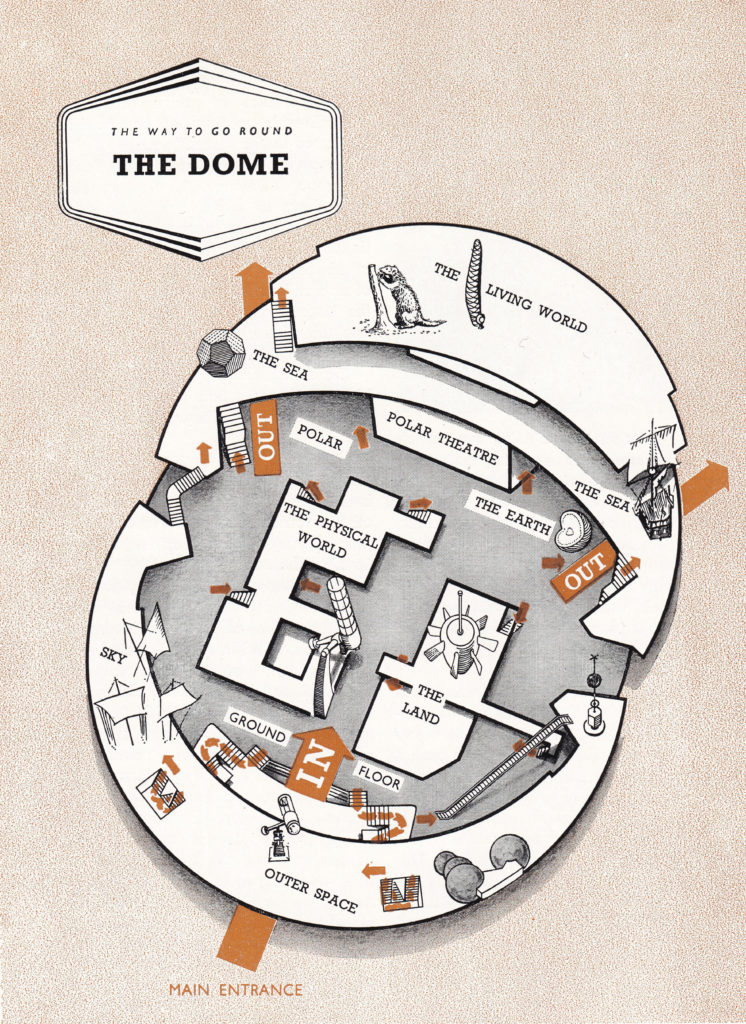

Now, after the Transport Pavilion, we will head to the Dome of Discovery:

View today from roughly the same location:

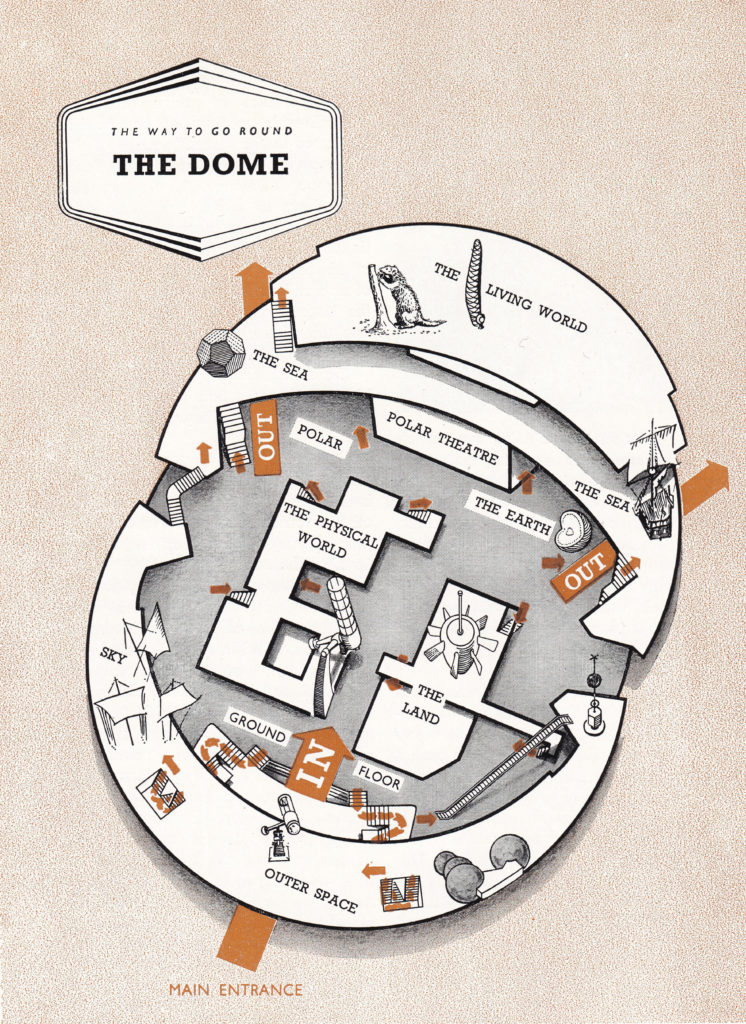

The theme of the Dome was discovery of the wider world. In the words of the guidebook “In shaping Britain and nurturing her, nature has been particularly moderate. We have no extremes of climate; our driest places are not deserts, our waterways are modest and our mountains would be lost in the shadows of the Andes. Yet, by some persistent anomaly, the British have always been lured to discovery and exploration by those very regions of the world where nature has been most extravagant or most severe – Livingstone by the jungles and lakes of Africa, Scott by the icy Ant-arctic, Sturt by Australia’s barren heart, Mallory by the supreme isolation of Everest”.

The Dome of Discovery told a sweeping story from the land and physical world through to outer space.

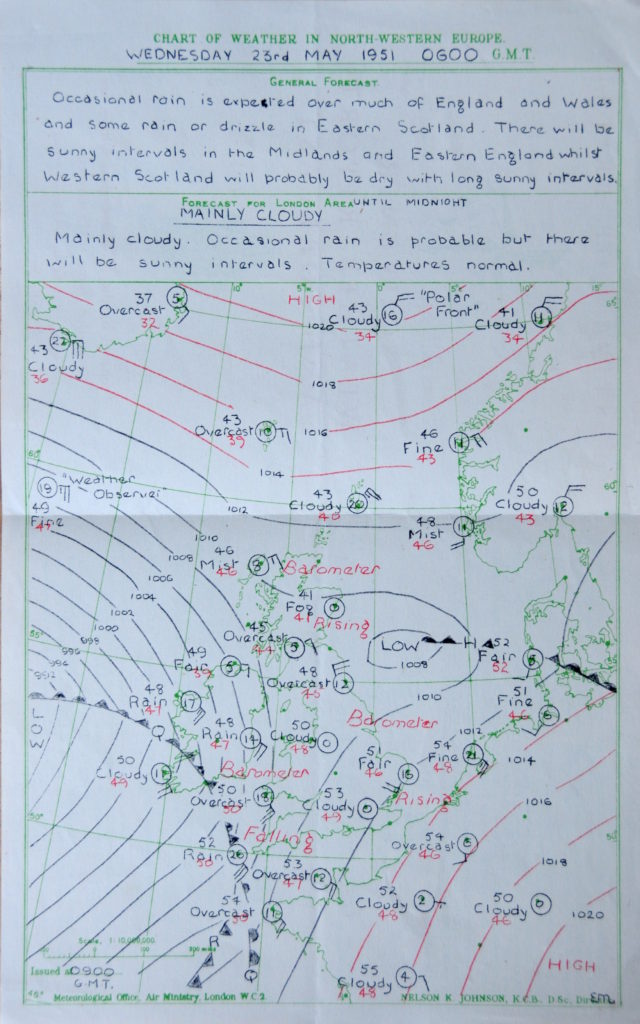

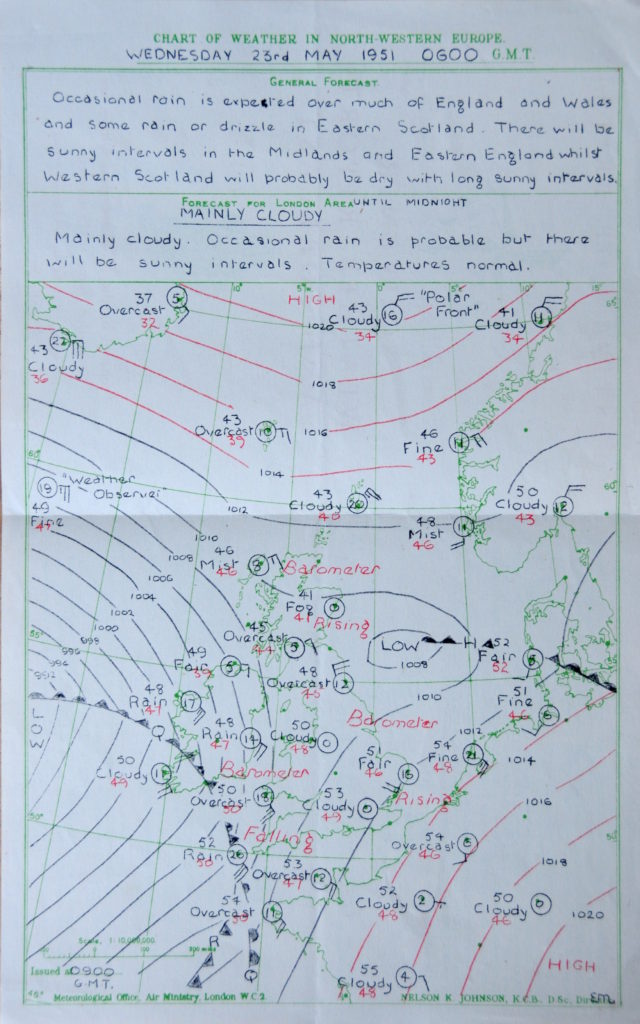

Topics covered ranged from Maps and Map Makers, Pest Control, Polar Science, Research at Sea, Weather Forecasting, Charles Darwin, Nuclear Power, Stars and Planets.

The Dome of Discovery was the only location at the Festival to show any displays covering the Commonwealth. Within the section on the land, there were subsections on Commonwealth Links and Commonwealth Agriculture. The emphasis though was still on the future Commonwealth rather than the past, although the description starts with “the great witness of British exploration by land is the Commonwealth of Nations” – I am not sure that the formation of the Commonwealth was by exploration alone, other reasons such as commercial, competition for land with other European nations, exploitation of resources etc. were not topics covered at the Festival of Britain.

Rather, the festival looked at how the Commonwealth is now bound by common ideas and ideals and using British enterprise in the development of sea lanes, air routes, railways, cables and radio – “a radio system which itself is part of our contribution to the welfare of mankind”.

As well as static displays there were practical demonstrations. The antennae on top of the Shot Tower was used to beam a radio signal to the moon and receive the signal after it had reflected from the surface. A cathode ray tube display was set-up in the Outer Space section of the Dome of Discovery and visitors could see the pulses transmitted and returned with a delay of two and a half seconds for the radio signal to reach the moon and return.

In the Sky section there was an operational weather forecasting unit and visitors could pick up forecasts for the day ahead. The forecast issued at the Dome of Discovery for Wednesday 23rd May 1951:

Mainly cloudy, occasional rain with sunny intervals – sums up British weather.

The Dome of Discovery was the final point on the upsteam circuit. The next point in the walk round is Pavilion 16 – The People of Britain which is part of the downstream circuit which I will cover in my next post.

There is hardly anything left to see today of the upstream circuit of the Festival of Britain – although perhaps the Embankment which was built and extended into the river using much of the rubble from the demolished south bank buildings is the only tangible reminder of the festival.

There are a couple of plaques that mark the festival. The first is at the point where the Skylon was located and reads “I saw a blade which rises in the sky held by hardly nothing at all”

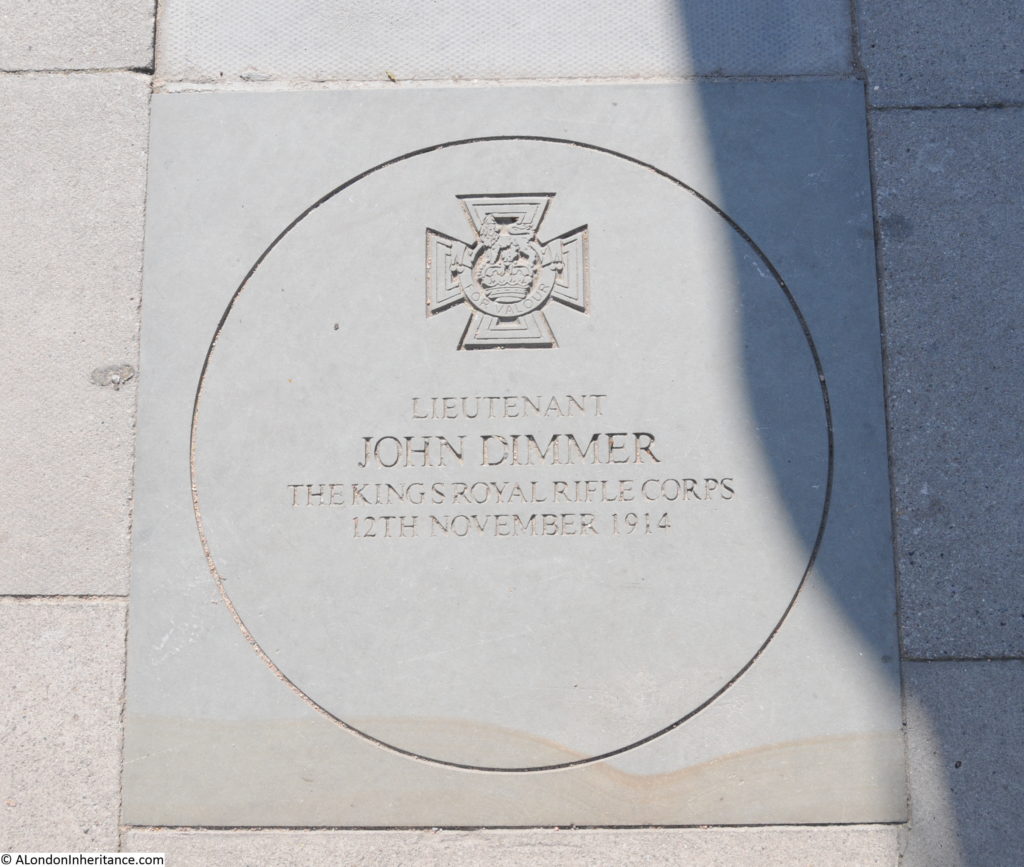

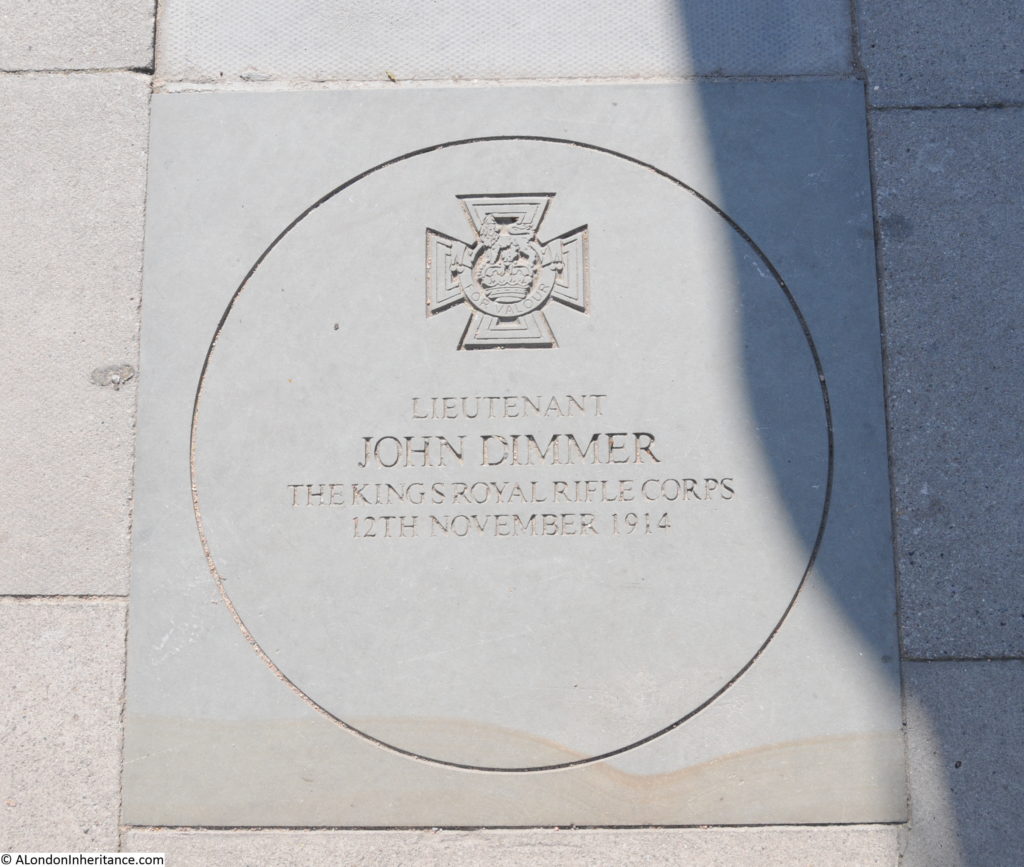

There is another plaque on the ground just in front of the Skylon plaque, nothing to do with the Festival of Britain, but still a fascinating story. This plaque is to Lieutenant John Dimmer who was born in Gloster Street, Lambeth and awarded the Victoria Cross for his actions at Klein Zillebeke, Belgium on the 12 November 1914.

The London Gazette published that “This officer served his Machine Gun during the attack on the 12th November 1914 at Klein Zillebeke until he had been shot five times, three times by shrapnel and twice by bullets, and continued at his post until his gun was destroyed”.

Lieutenant John Dimmer would later be killed in action on the 21st March 1918 whilst commanding and leading the 2nd / 4th Battalion of the Royal Berkshire Regiment at Marteville, near St Quentin.

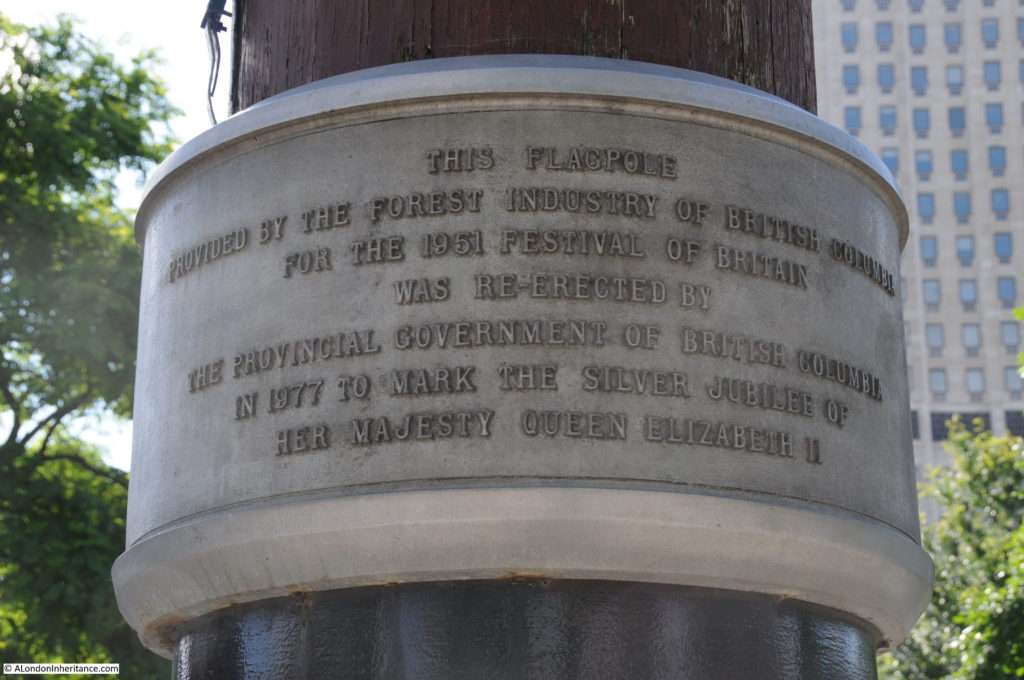

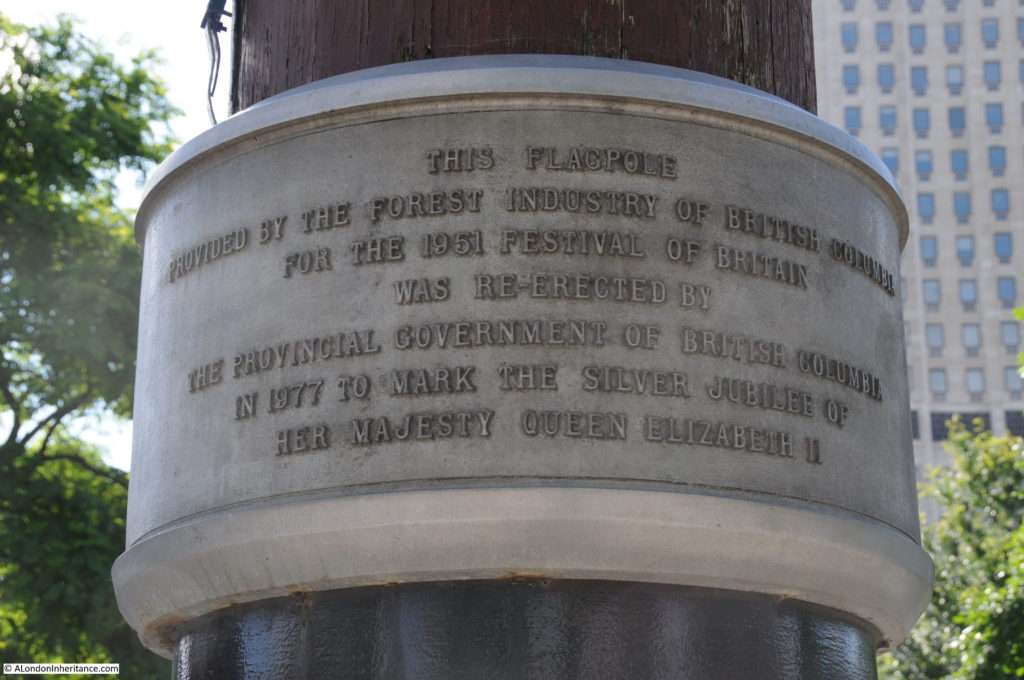

Close by the above plaques is a large flagpole which is from the Festival of Britain. The plaque reads:

“The flagpole provided by the Forest Industry of British Columbia for the 1951 Festival of Britain was re-erected by the Provincial Government of British Columbia in 1977 to mark the silver jubilee of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II”.

The flag pole was 108 feet long and weighed five and a half tons. It was delivered by ship from Canada to the Surrey Docks from where it was floated up river to the Festival site, towed behind a tug.

The flagpole on the right of the photo. The Skylon was just to the left of the flagpole.

There is another plaque which must qualify as one of the hardest to read in London.

The plaque reads:

The construction of the new portion of the river wall was begun by the Right Hon Herbert Morrison on the 17th January 1949

Chairman of the London County Council Walter R. Owen

Chairman of the South Bank sub-committee J. Hayward

Chairman of the Central Purpose Committee Edwin Bayliss

Clerk of the Council J.R. Howard Roberts

Chief Engineer J. Rawlinson

Contractors Richard Costain Limited

Granite Supplier Cooper Wettern & Co Limited

Photo showing the location of the plaque close to the London Eye.

There was another plaque marking the Dome of Discovery, although this plaque seems to have disappeared. There is a photo on the excellent London Remembers site.

There are information boards in the Jubilee Gardens which have some information on the area, however I have not found any other references to the Festival of Britain across this part of the site – if there are, please let me know.

In my next post we will walk through to the Downstream Circuit – The People.

alondoninheritance.com

Image credit: London Metropolitan Archives, City of London: catalogue ref: SC_PHL_04_15_53_27D

Image credit: London Metropolitan Archives, City of London: catalogue ref: SC_PHL_04_15_53_27D