A short distance from Waterloo Station, there are some wonderful streets. Lined with terrace housing that date back to the 19th and early 20th centuries. A couple of weeks ago, I went for a walk along these streets, starting at Roupell Street and ending at Aquinas Street.

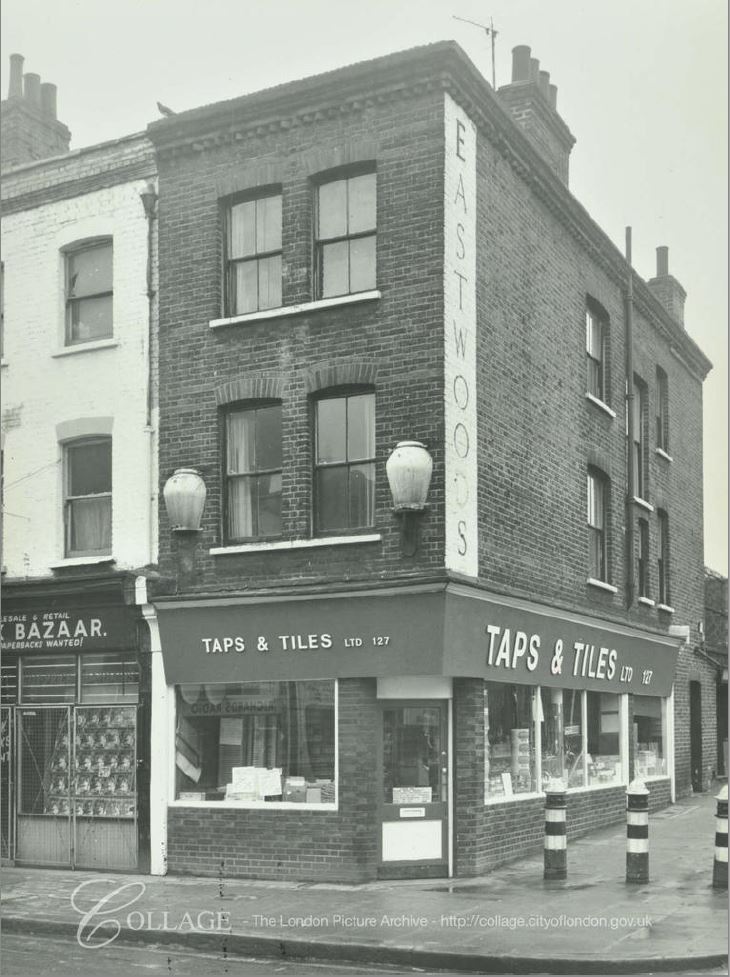

The reason for the visit was to revisit the site of a 1986 photo of a men’s hairdresser on the corner of Roupell Street and Cornwall Road:

The same view 35 years later in June 2021:

What was then, simply a “mens hairdresser” is now “First Barber”. Really good to see that the same type of business is in operation thirty five years later.

Getting your hair cut is a service which cannot be provided over the Internet, so hairdressers / barbers are the type of shops that will hopefully be on the streets for many years to come.

It did though get me thinking about name changes. In the 1980s I went to a hairdressers, or a hair stylist (see my post on the Hairdressers of 1980s London for lots more examples). When did the shop for a men’s hair cut change from a hairdresser to a barber? One of those gradual changes that you do not really notice until you compare street scenes.

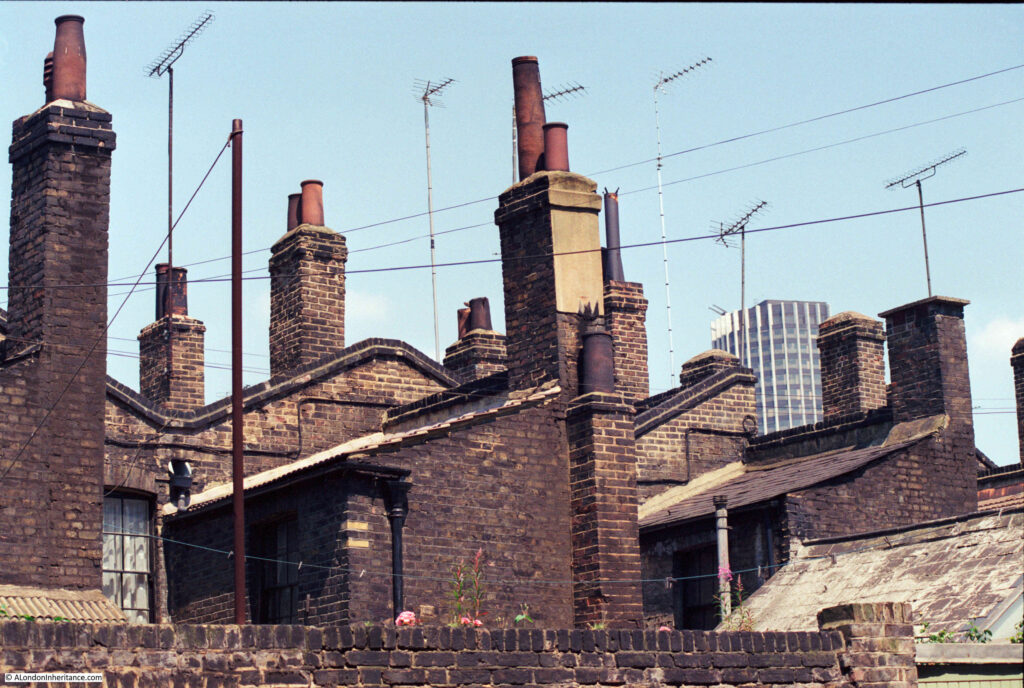

Another 1986 photo shows the rear of the houses in Roupell Street. A jumble of chimneys and TV aerials:

I walked down Brad Street, which runs behind the southern side of Roupell Street, trying to find the same chimney combination as in the 1986 photo, but there seem to have been many subtle changes. The following photo is the nearest I could get:

The centre tower in the 1986 photo was Kings Reach Tower, the home of IPC Media, publisher of a vast range of titles from Country Life to NME. It was sold some years ago, had additional floors added to the top (hence the difference in height between the two photos) and is now apartments.

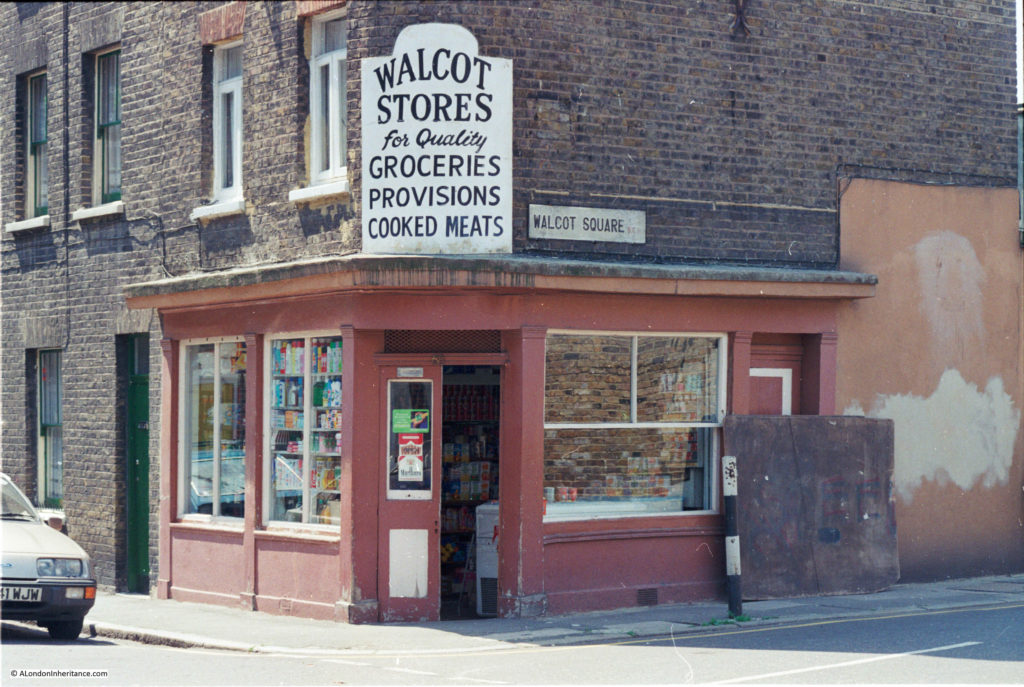

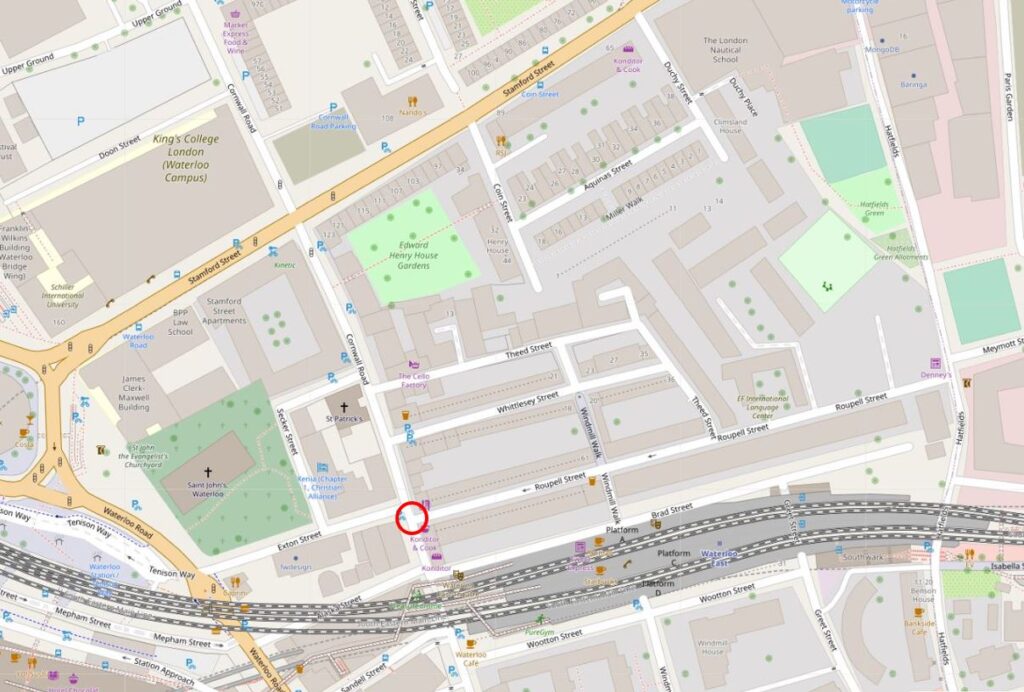

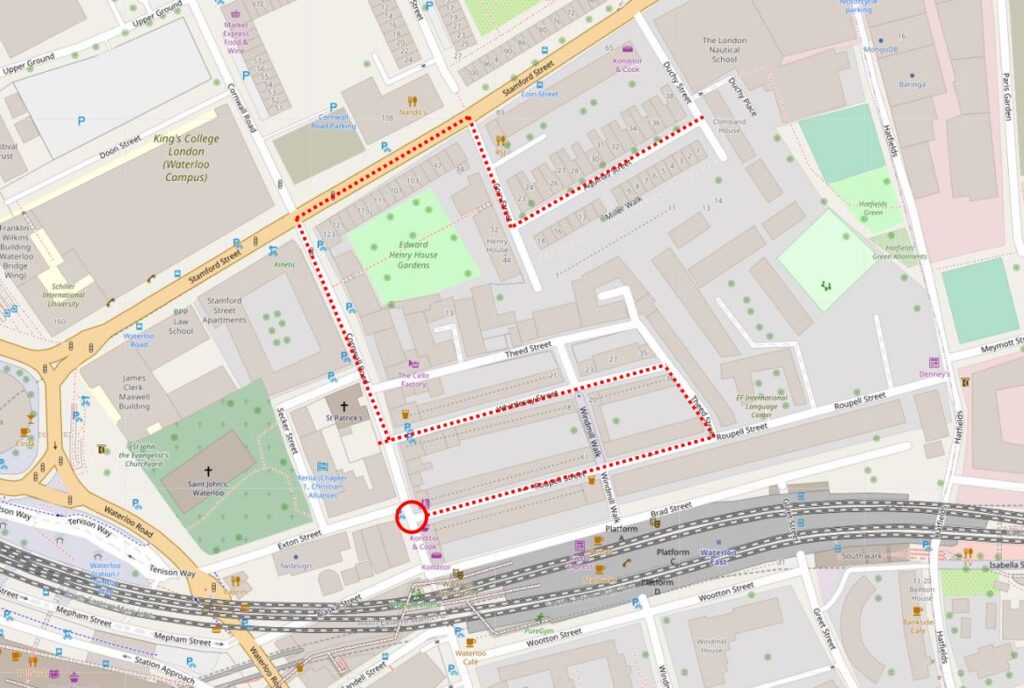

The location of the hairdressers / barbers is shown in the following map (red circle) (Map © OpenStreetMap contributors):

Roupell Street runs to the right of the red circle, and Waterloo East station is below.

Part of a roundabout can be seen on the left edge of the map. This is the large roundabout at the southern end of Waterloo Bridge, and Waterloo Station is just off the map to the left.

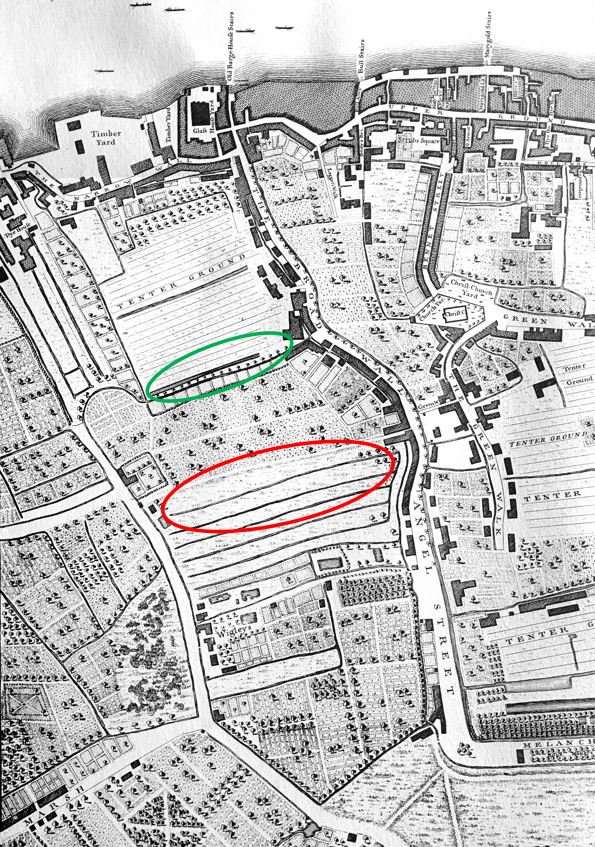

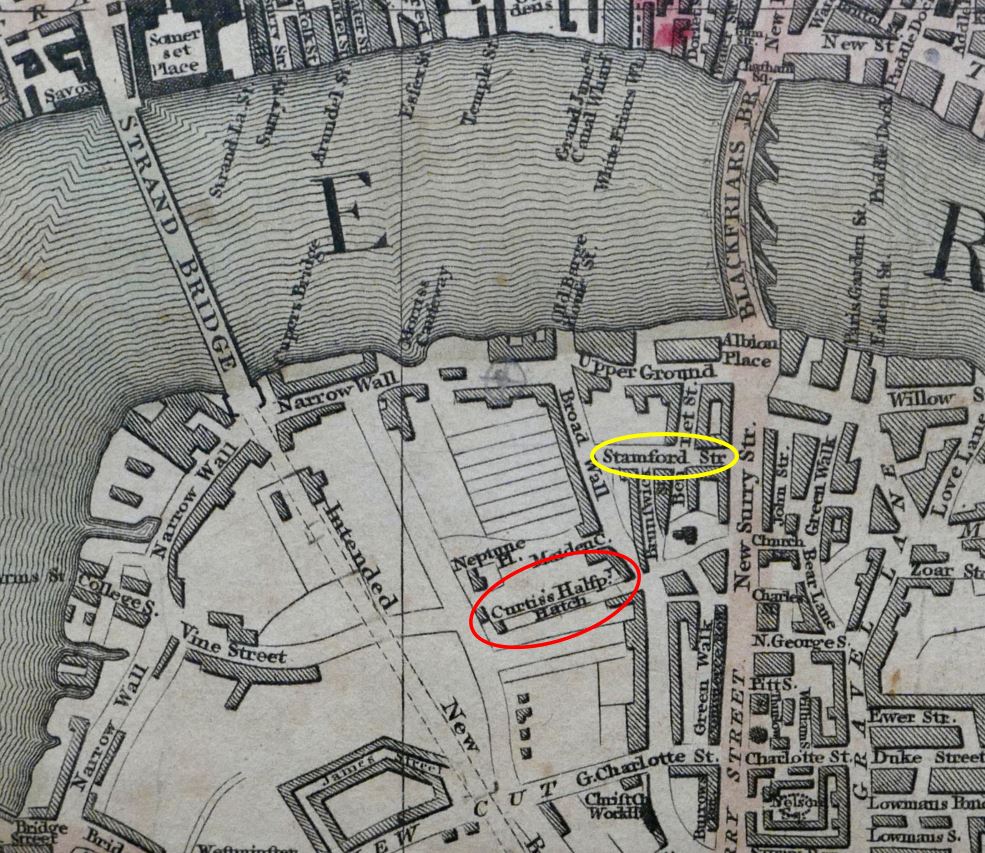

Development of the area is relatively recent. It was long part of the area known as Lambeth Marsh. An area of low lying land, with many streams and ditches, and marshy ground. During the 17th century, much of the area was being converted to different forms of agricultural use, and in 1746, Roqcues map shows some streets, limited building, and a network of fields (red oval is future location of Roupell Street and green oval future location of Aquinas Street, which I will be coming to later in the post).

By 1816, Smith’s New Map of London was showing increased building in the area, however the area around what will become Roupell Street (red oval) was still open land, with what may have been large plots extending back from the houses on Broad Wall.

The yellow oval is around the first stretch of Stamford Street. This is the road that runs to the north of the area I am walking, and is a busy road connecting Blackfriars Road and Waterloo Road.

Note the Strand Bridge. This was the recently built first bridge on the site of what is now Waterloo Bridge. Also, running south from Strand Bridge is the outline of a street labelled “Intended New Road”. This is the future Waterloo Road.

In the above map, there is a track called Curtis’s Halfpenny Hatch where the future Roupell Street would be located.

This was named after a William Curtis who was the founder of a Botanic Gardens in the area. It was a suitable location for aquatic and bog plants as the area was low lying. The Halfpenny element of the name was the cost to use the route when it was previously a short cut through the agricultural land on either side.

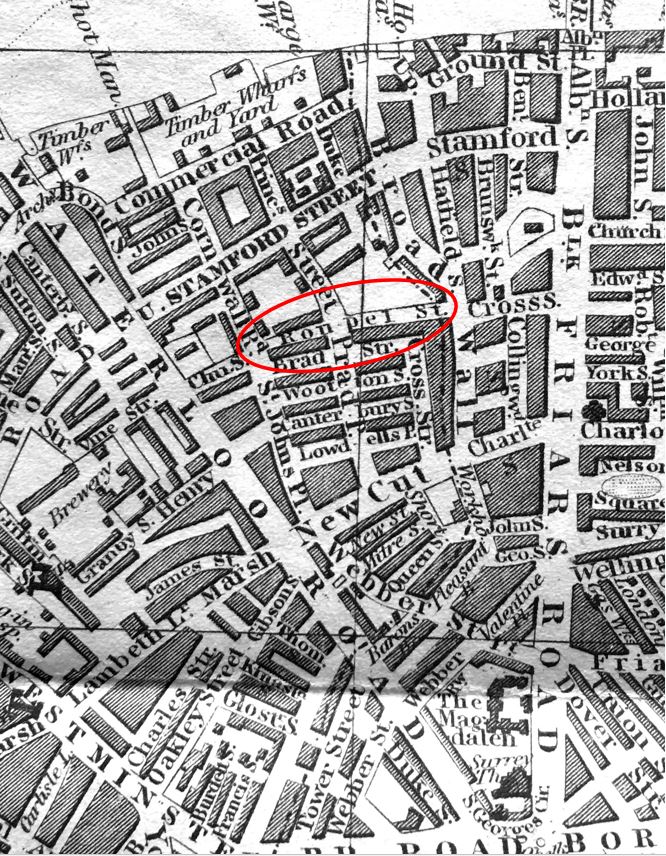

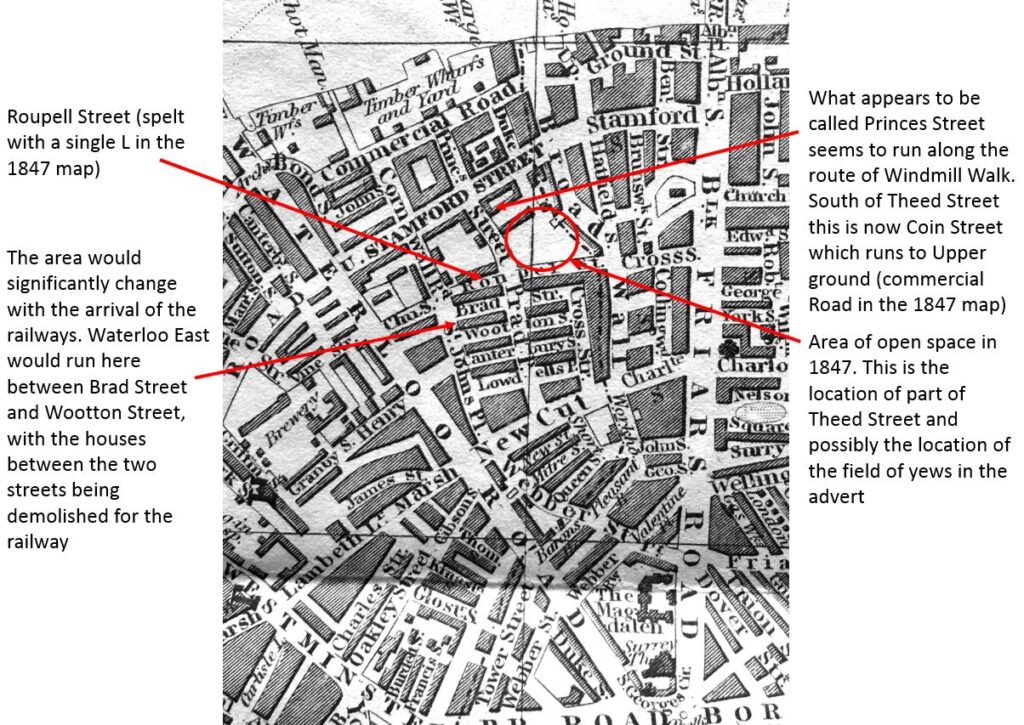

The 19th century would bring considerable change and development to the area with the arrival of Waterloo Station, however this had not yet been built by the time of the 1847 edition of Reynolds’s Splendid New Map Of London. Roupel Street had arrived, but apparently not yet fully built, along with the streets that would fill in the area to the north (more on this later in the post).

Between the 1816 and 1847 maps, Stamford Street was completed linking Blackfriars and the now completed Waterloo Road.

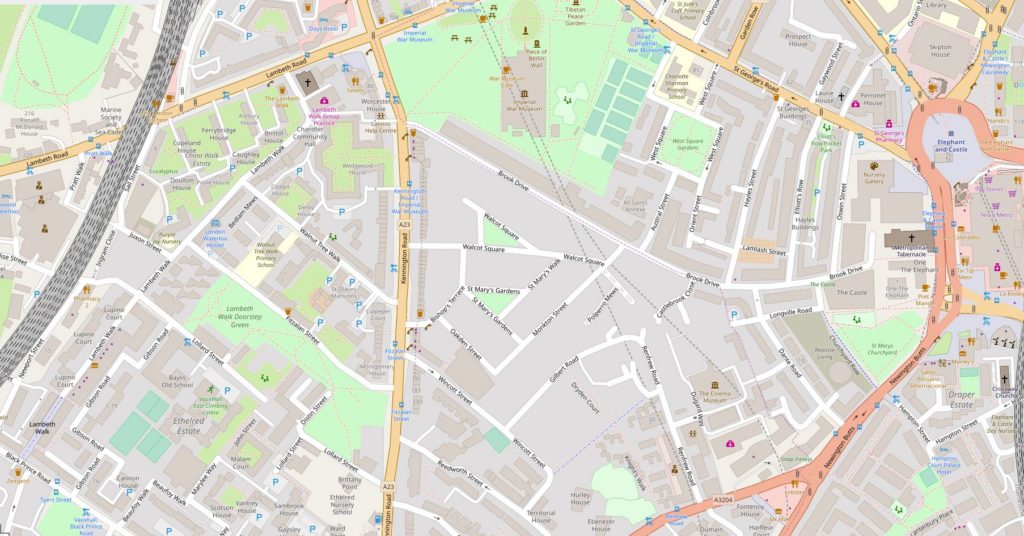

To explore the area, I went for a walk from Roupell Street to Aquinas Street, shown by the dotted red line in the following map, starting at the red circled location of the hairdressers (Map © OpenStreetMap contributors).

This is the full view of the corner building with the barbers at street level:

On the opposite corner is an identical building, even with the same bricked windows:

With a bakers shop now occupying the corner position.

Looking down the full length of Roupell Street:

The name of the street comes from John Roupell, who purchased the land and built the estate in the early 19th century.

John Roupell had a Bankside metal works, and seems to have inherited the wealth needed to pay £8,000 for the land through his wife’s family.

The street was laid out and construction started around 1824. when John Roupell was 64. The houses in the street seem to have been occupied from the early 1830s as from 1835 onwards, references to those living in the street, or local events, start appearing in the press. One strange mention concerns a murder in a pub garden in Broad Wall, at the eastern end of Roupell Street, when during the inquest, one witness stated:

“John Bingley deposed he is a private watchman. On Sunday morning, about twenty minutes after two, witness was in Roupell-street; he heard a voice – apparently that of a women – exclaim ‘Here’s a villain! – he has got me down and is trying to kill me’.

By the Coroner – Did you hear any other words?

Witness – Yes, i heard the same voice say ‘Come to me’ and then in a fainter tone, ‘Have mercy on me’.

Apparently John Bingley thought it was a drunken row, and took no notice of the matter, he did not see any person answering the description of the deceased either alone, or accompanied by any other person – he does not sound perhaps the most pro-active watchman that you would want to employ on London’s streets.

Roupell built two storey terrace housing. Brick built, directly onto the street with no front garden or a small area protected by railings. Open the front door and you are directly on the street.

The first time that Roupell Street features in London’s newspapers is when the London Evening Standard reported, on the 1st June 1829, the impact of Roupell’s builders working extra hours:

“On Saturday evening a fire broke out in Roupell-street in one of the new houses belonging to Mr Roupell. On the first alarm, the engines of the Palladium and West of England fire-offices promptly attended, and by the aid of a plentiful supply of water the flames were prevented from spreading, and eventually subdued in about an hour, but not before one of the houses, nearly in a finished state, was totally destroyed and the adjoining one considerably damaged.

The fire originated under these circumstances:- Mr Roupell had bound himself by contract to have both houses finished by a given time, and the period fast approaching, men were employed to work beyond the usual hours.

Some of them were in the act of pitching some gutters, when the pot boiled over and set fire to the shavings and wood with such rapidity that it was with some difficulty all the workmen succeeded in effecting their escape.

Of course none of the houses were insured, as they were in an unfinished state.”

The street was quickly finished after the fire. By the time of the 1841 census, Roupell Street seems to have had a good population, with 250 people recorded in the census as living in the street.

Roupell had built the street for what were described as “artisan workers” and the 1841 census provides a view of the professions of what must have been some of the first people living in the street. This included; painters, labourers, clerks, printers, bakers, carpenters, bricklayers, compositors, paper hanger, hatter, an excise officer, lighterman, warehouseman – all the typical jobs that you expect to find in such a street in 1840s London.

This Citroen has been parked on the street for many years, and provides one of the most photographed views of the street.

Walking further down Roupell Street, and a pedestrian walkway that was once a street cuts across. This is Windmill Walk.

On either side of the northern entrance to Windmill Walk are two buildings that have what appears to be shop fronts, along with what could be a very faded painted advertising sign on the wall.

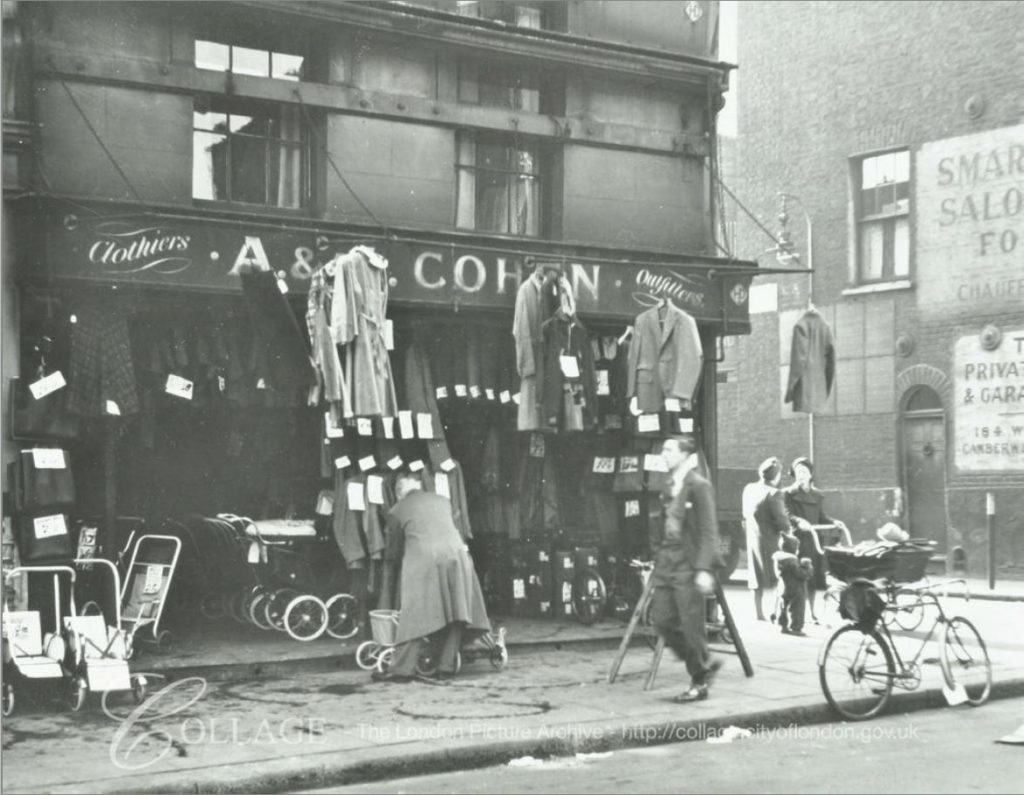

The 1910 Post Office Directory confirms that these were shops, and the businesses that operated in them at the start of the 20th century.

At number 61 (nearest the camera) was john Bowen Walters – Dairyman and at number 62 was Arthur Edward Cowdery – Baker.

The 2007 Conservation Area Statement records that the shop fronts are replacement / reproductions of the originals.

Directly across the street from the above old shops, is the Kings Arms, a brilliant local pub:

The Kings Arms was part of the original build of the street and has retained the same name since opening in the 1830s.

The first reference to the pub in the press provides a fascinating view of the agricultural nature of the area. An advert from the Morning Advertiser on the 22nd March 1836:

“Broadwall, Blackfriars-road – to Timber-merchants, Hard Wood-turners, Veneer-sawyers and Others, By Mr. C. COULTON on the Premises, a field opposite the King’s Arms, Roupell-street, Broadwall, on THURSDAY, March 24, at Twelve.

COMPRISING two hundred Yew Trees – to be paid for on the fall of the hammer. may be viewed till the sale, and Catalogues had of the Auctioneer, No 32, Union-street, Borough”.

The advert shows that in the 1830s, reminders of the old agricultural nature of this part of Lambeth could still be found. Two hundred yew trees sounds like a reasonable number so this was not a small field. I do not believe they like water logged conditions, so the typical wet conditions of the Lambeth Marsh were also disappearing.

The trees were almost certainly being sold to release the field for building, as in the late 1830s and 1840s, the remaining open space was being built on.

The majority of Roupell Street has a uniform appearance, however walking further east along the street and there is a three storey pair of houses.

These houses were not part of the original construction of the street as within the triangular pediment at the top of the building there is the date 1891 which is presumably the date of construction.

The two houses retain the same width as those along the rest of the street and the doors and windows are also much the same, so it may be that in 1891 only the top floor and pediment was added to two existing terrace houses. Perhaps some late 19th century home improvements.

John Roupell died on the 23rd December 1835, when the St James’s Chronicle reported that he had died in his 75th year at his own residence in Roupell Street. Along with Roupell Street, he had a substantial portfolio of land and property in south London, part of which gets mentioned in a news report when his son Richard Palmer Roupell was a witness to a possible murder in his grounds at Norwood. At the inquest, Richard Palmer Roupell was described as a lead merchant of Cross-street, Blackfriars who has a country residence at Brixton Hill.

It may have been Richard Palmer Roupell who developed Theed Street which runs north from Roupell Street:

Theed Street still consists of a terrace of two storey houses, however there is a very different treatment at the top of the buildings where instead of the rise and fall of the triangular wall in Roupell Street, Theed Street has a top wall blanking off the roof at the rear, giving the impression of a more substantial row of houses.

According to Reynolds’s Splendid New Map Of London published in 1847, Theed Street had not yet been built. See the annotated map below:

I am not sure whether the 1847 map is correct. Greenwood’s map from 1828 shows what would become Theed Street as an unnamed street running between two fields. It could be that in 1847 it was still unnamed and running between fields and therefore not considered worth recording – one of the challenges of trying to interpret maps of different scales and over the years as London changes.

Greenwood’s map does show that Roupell Street was originally called Navarino Street (after a naval sea battle fought by the British and allies against the Ottoman and Egyptian forces in the Greek War of Independence in 1827). This was in 1828, and Roupell seems to have quickly changed the name of the street.

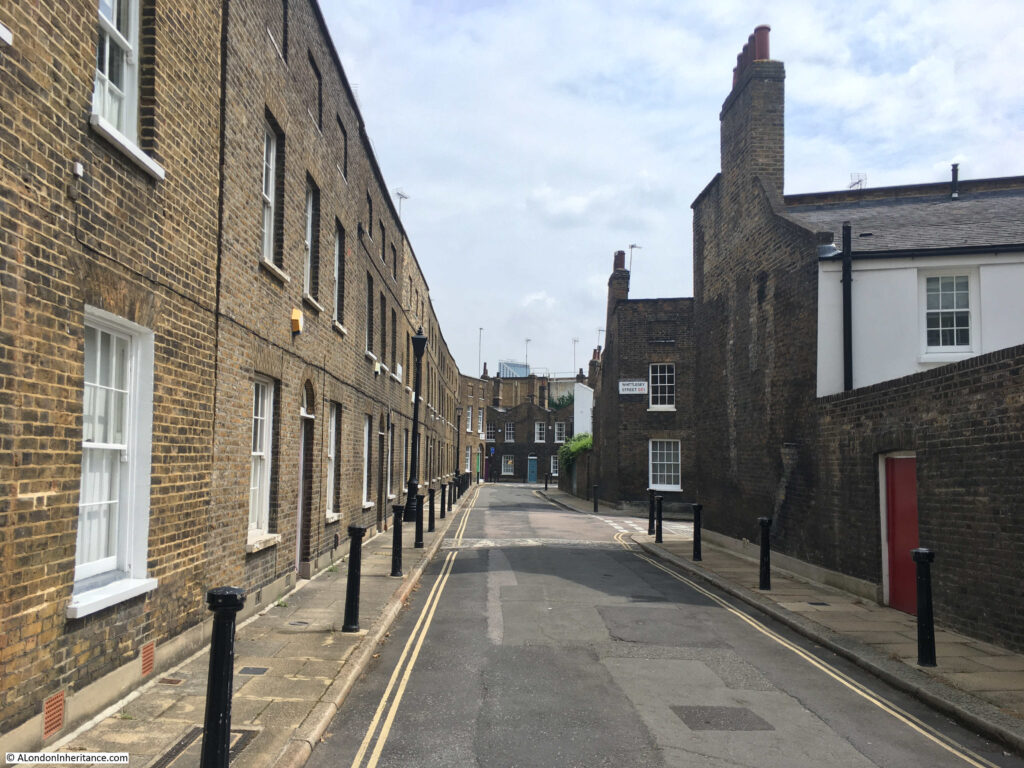

Branching off Theed Street is Whittlesey Street which continues the same architectural style of Theed Street:

Looking back up Theed Street towards Roupell Street – not a parked car in sight which adds considerably to the view:

In the above photo, the house on the right is to the same design as those in Theed Street, and the way that the top line of brick hides the rear slopping roof can be seen.

Not what you expect to see running across the street of such a densely built area:

Where Windmill Walk crosses Whittlesey Street:

The towers in the distance of the above photo are the new blocks recently built around the Shell Centre site on the Southbank.

Reaching the end of Whittlesey Street, where the street meets Cornwall Road, the following photo is looking south with the railway bridge over the street and above that, the pedestrian walkways that take travelers down to the platforms of Waterloo East.

On the corner of Whittlesey Street and Cornwall Road is another pub – the White Hart:

Another pub that has been here since the development of the area and that has retained the same name. The first record I can find of the pub dates from the 25th January 1849 when they placed an advert in the Morning Advertiser for a Barman or Under-Barman. In the advert the pub was described as “a respectable Tavern”.

From here, I am going to take a short walk from the area of Roupell’s developments as there is another street with some fantastic architecture.

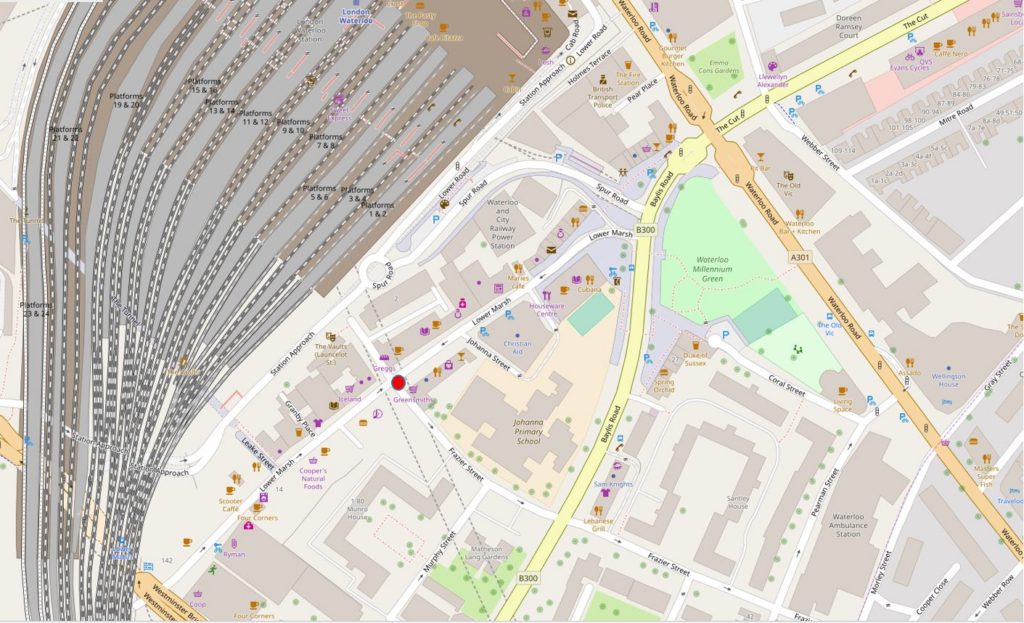

Following the route in the map shown earlier in the post, I walked north along Cornwall Road to turn right onto Stamford Street, then south down Coin Street to find Aquinas Street:

Aquinas Street is early 20th century, so later than Roupell, Theed and Whittlesey Streets, but like these early 19th century streets, Aquinas Street is lined by rows of terrace houses of a continuous and unique design.

This is the south side of the street:

The south side of the street dates from 1911, and in the conservation area statement are described as Neo-Georgian, with their original doors, sash windows and railings. The terrace is Grade II listed.

The northern side of the street has a continuous terrace of houses, but of a very different style:

Substantial three storeys, each with a full height bay. They are not what you expect to find in this part of Lambeth and represent a rare example of a surviving, continuous terrace of houses dating from the early decades of the 20th century.

Aquinas Street is a perfect example of some of the wonderful streets that can be found by turning off the main streets of the city.

I started the post with the hairdressers / barbers on the corner of Roupell Street, so I will conclude the post by returning to the Roupell family.

John Roupell, the original developer of the estate, died in 1835. He died a wealthy man.

His son Richard Palmer Roupell had four children, however it appears that John Roupell was unaware of his grandchildren as Richard had the children with Sarah Crane who was recorded as the daughter of a carpenter. John Roupell would apparently have disapproved of this match, so Richard hid the relationship from him.

One of the four sons of Richard Roupell was William Roupell. He discovered that his father left his estate to his brother Richard, who was the only son born after Richard and Sarah had married (after John Roupell had died).

Richard forged his father’s will to leave his estate to his mother with Richard as executor. He was able to borrow against the estate. He also became an MP for Lambeth.

He had substantial debts and when those who had lent him money called for the debts to be repaid, he fled to Spain. He was persuaded to return, and then tried at the Old Bailey in 1862.

The trial gained considerable publicity, because of the level of forgeries, and because Roupell had been an MP.

An account of the trial was published, published in 1862 and described as “From the shorthand notes of Mr. G. Blagrave Snell – Shorthand writer to the Court of Bankruptcy”. The introduction to the account provides an indication of the sensational nature of the trial:

“The following pages contain the whole of the startling details of one of the most extraordinary series of forgeries that was ever disclosed in a court of justice in this country. No work of fiction, it may safely be said, ever was conceived, in which all the incidents that go to make up a tale of thrilling interest, can be more striking than is this bare, unvarnished tale of truth.

The principal party concerned in it was but the other day a member of Parliament, and a man of whom many prophesised that it would be no long time ere he would rise to distinction in the senate; but who by embarking on a career of reckless profligacy, has brought down absolute ruin upon himself, and upon his family an amount of calamity wholly undeserved, which would have been far greater had he not surrendered to justice by placing himself in the felon’s dock.

It was but recently that the pubic were surprised at the resignation of the Member for Lambeth. They little knew the tale that lay behind that resignation. They little knew that forgery and fraud had been the common paths and beaten ways of William Roupell for seven long years; that he had wasted the patrimony of his family, and had reduced them to comparative poverty even before his father’s death.

At length the fatal truth came out, and he was obliged either to face his father’s executors or fly the country. The family property had been fraudulently sold, and it was only when overwhelmed with difficulties, pecuniary and otherwise, that he resolved to confess the whole truth, even at the bar of the court of justice”.

A dramatic end to a once wealthy family, however we still have John Roupell’s original development as a memorial to his achievements, rather than his fraudulent grandson.