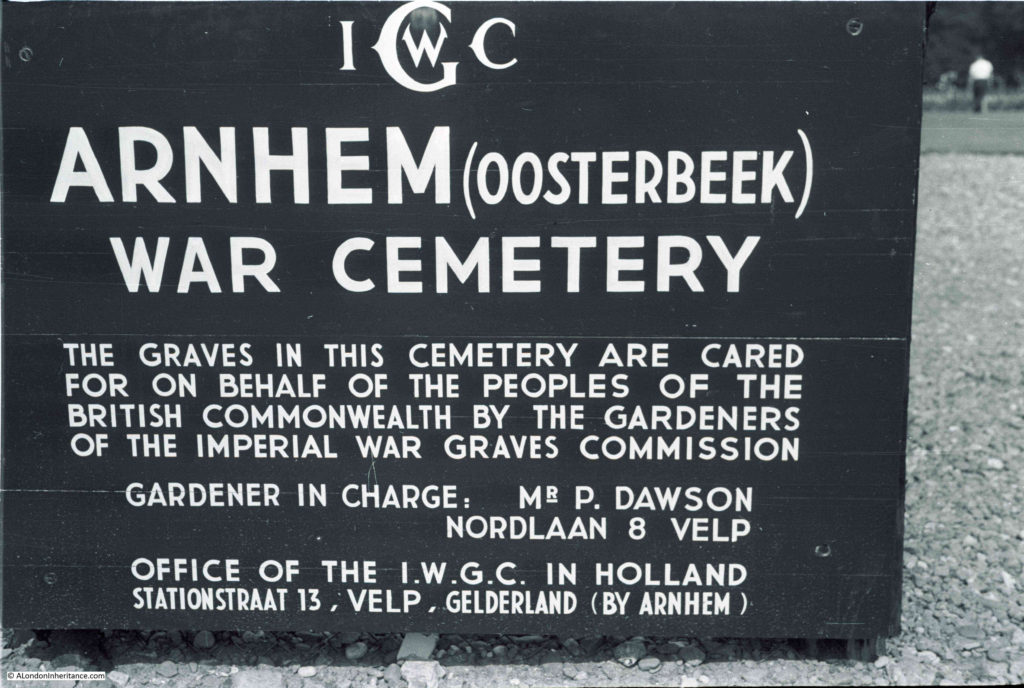

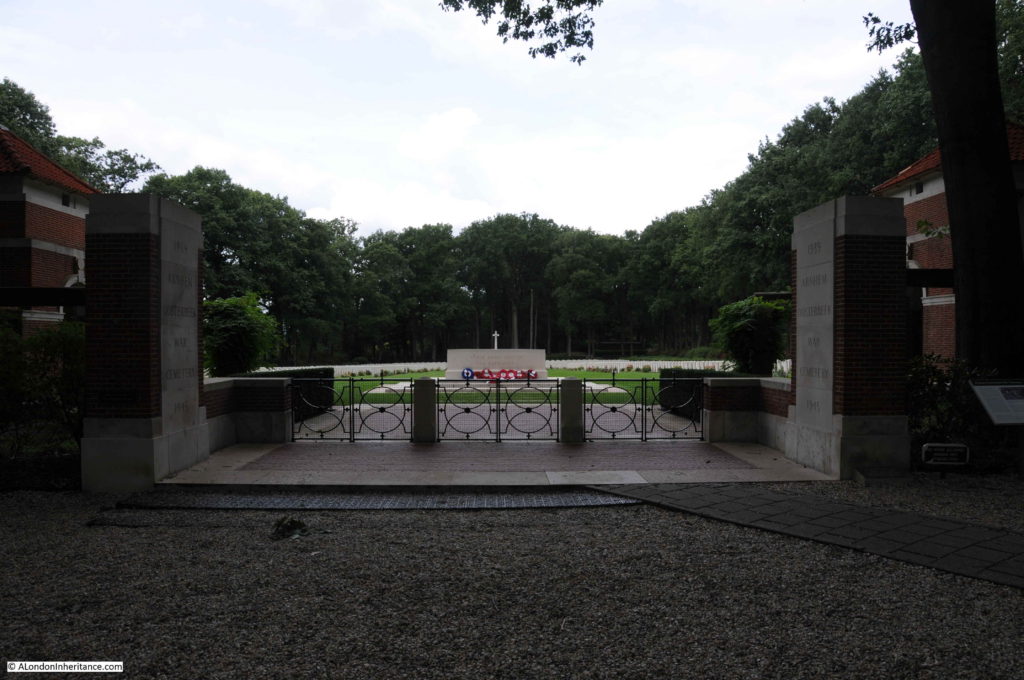

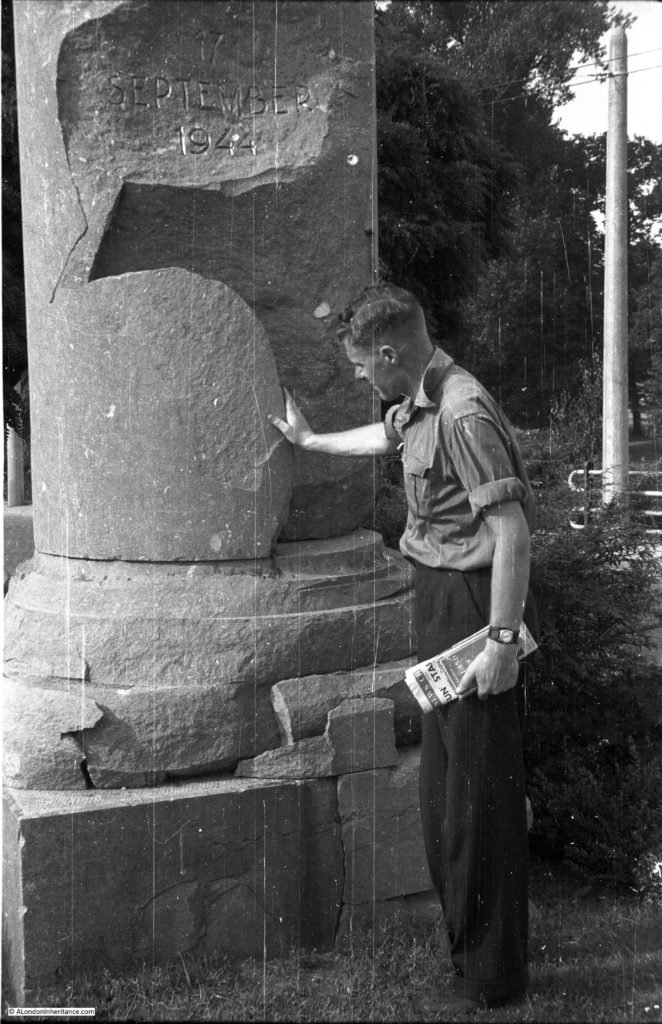

Last year, I visited the Netherlands to photograph the locations that my father photographed in 1952. This included the Oosterbeek war graves cemetery on the outskirts of Arnhem where those who died during Operation Market Garden are buried.

Those buried here were not just casualties from the fighting on the ground, but also those who time after time flew supply missions and sustained terrible casualties as they had to fly low and slow to deliver an accurate drop.

In one of my father’s photographs, there is a temporary cross with multiple names, seen below to the left of the photo.

I did discover that they were an aircrew, probably flying supply missions, but could find no further information.

I was really pleased to be contacted by Paul Brooker, the nephew of Richard Bond, the name just visible at the bottom of the list of names in my father’s photo.

Paul has researched the story of Richard, and the aircrew named on the temporary cross, and has uncovered a remarkable story of bravery, so for today’s post, I would like to hand over to Paul to tell their fascinating story.

Richard Bond at Arnhem

Richard (Dick) Bond was the elder of two brothers by 3 years, and he enlisted into the RAF reserves as a fitter on 3rd September 1940, at the time that the Battle of Britain was coming to its climax. Whether it was the fact that his brother Stan was training as a Navigator I don’t know, but he subsequently started training as a Flight Engineer on 21st December 1942, later joining A. V. Roe & Co (AVRO) for a six week period on 25th October 1943. He qualified as a Flight Engineer on 25th November 1943, just 3 months after his brothers’ death. Married, his picture gives me the impression of the quieter elder brother. Much of the following information was unknown to my family until I started my research in 1994.

At the end of 1943 he joined 1665 Heavy Conversion Unit at Woolfox Lodge in Rutland where he met up with his first crew and flew his first Stirling. Although some of the crew members were to change over the coming months, he stayed with his pilot, Bill Baker right through to the end. Apparently Bill was an American pilot who already owned his own aircraft in the States, and he volunteered with the Royal Canadian Air Force as a way of “seeing the action.”

On the 7th January 1944 the crew joined their first operational squadron, 196 at Tarrant Rushton. In the previous months the Stirlings had taken such a mauling that they had been withdrawn from front line bombing duties due to their low ceiling capability of only some 16,000ft. The introduction of the Lancaster in greater numbers, with its higher ceiling and greater bomb capacity meant that the Stirling was now being used to good effect in a transport role.

Their first Operational Mission was flown from Hurn, just a short hop south of Tarrant Rushton on 8th February 1944 in aircraft W ZO. (See picture above) The log simply states “Special Mission-Low Level S. France.” This was to be the first of a number of night-time flights deep into enemy occupied France at rooftop height. Five hours forty minutes of intense concentration, especially for the pilot! Although it was generally believed that they were dropping supplies of arms and ammunition to the French resistance, together with SOE agents the exact details are unclear, indeed the full information of most of these low level drops remains covered by the Official Secrets Act.

Throughout much of early 1944 many supply drops were made to France by Stirlings in readiness for the coming invasion. Dick’s Log also shows an increasing number of flights were made towing Horsa Gliders and paratroop dropping – the shape of things to come. On 14th March 1944, 196 Sqn moved from Tarrant Rushton to Keevil where flying took place almost every day, practicing for the invasion. It is interesting to note from the log that flying appears to come to an abrupt halt after 27th May. This is explained by the need to get all aircraft serviced and fully ready to take part in what was to become known as D Day. During this intervening week all personnel were confined to the airfield. Secrecy was paramount and nobody was allowed in or out of the base without a very good reason. Finally, the aircraft were taken up for a short air test on 3rd June 1944.

Dick’s involvement with D Day actually began the night before when 20 troops together with their kit, 9 containers and a bike(!) were loaded into the aircraft. Along with many others from 196 & 299 Sqns, the Stirlings thundered down the Keevil runway and into the night sky on “Operation Tonga.” The only information that I originally had about the destination of this trip was that Operation Tonga involved dropping troops in the dead of night on “Drop Zone N.” Where was Drop Zone N?

In 1994, 50 years after D Day I went to France for the 50th Anniversary of D Day. My first stop in Normandy was the Cafe Gandrée at Ranville, next to what has now become known as “Pegasus Bridge” after the Flying Horse emblem of the Paratroops insignia. This was the first house in the first village to be liberated from German tyranny. Buying a souvenir map of Normandy I was astounded to realise that Drop Zone N was within 800m of where I sat. Dick’s troops must have been involved with the liberation of the first French village!

However, things did not all go smoothly. The anti-aircraft fire was intense, and the log reads “Two inner engines knocked out by flak. Nav. and Bomb Aimer bailed out over France. Crash landed at RAF Ford.” This matter-of-fact report must cover a great deal of fear and anxiety. According to family history, the aircraft had taken a bit of a pasting, and the intercom was u/s, the pilot, Bill Baker, said “prepare to bail out”, unfortunately the Navigator and Bomb Aimer only heard part of the message and they bailed out over the English Channel in the early hours of 6th June and were drowned. Richard Luff DFC, the Squadron Bomb Aimer was never found and his name is remembered along with all other aircrew with no known grave on the RAF Runneymead Memorial overlooking the River Thames near Windsor. He also took with him the whereabouts of a squadron sweepstake! Before D Day they had apparently taken bets on the time and date of the Normandy Invasion. The winner was denied his money as nobody knew where Richard Luff had left the takings!

Richard Luff was not normally part of my Uncle’s crew. Apparently, so I am advised by surviving 196 Sqn members, Richard Luff was the Squadron Bomb Aimer, so perhaps he was making sure he got in on the event! My Uncle’s pilot, Bill Baker, was already an experienced pilot before he came over from America, so perhaps he wanted to go with a reliable pilot! This is just my guessing, we shall never know.

Flying Officer Anderson, the Navigator, was washed up at Calais three weeks later and is now buried in the Canadian War Cemetery on the cliffs overlooking Calais.

The remaining crew then fought to bring their stricken aircraft home, throwing out guns, ammunition, indeed anything they could remove, into the English Channel. They finally made land at 02.28am, crashing just short of the airfield at RAF Ford. When you realise that Ford is only 1/2 mile from the sea, and that they couldn’t make it to the airfield, you begin to understand how close they came to ditching – no fun in the dead of night. The crew were given the customary week’s compassionate leave, but how does one get over leaving part of your crew in the English Channel?

After a week Dick was back to flying again, carrying out three more low level Special Missions to France, dropping containers and panniers for the SOE. On the 8th August, Dick and Bill Baker were transferred to 570 Sqn at Harwell where they teamed up with an existing crew who had lost their pilot due to sickness. This crew were to remain together until the end. A further three missions were flown to France during August and September before the log shows the final entries.

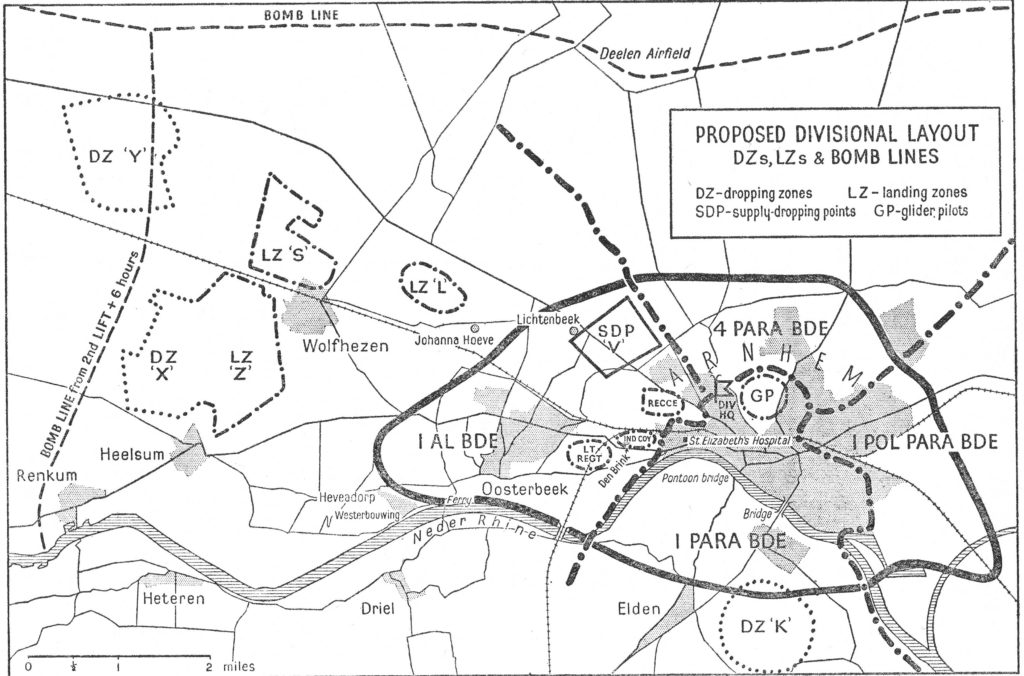

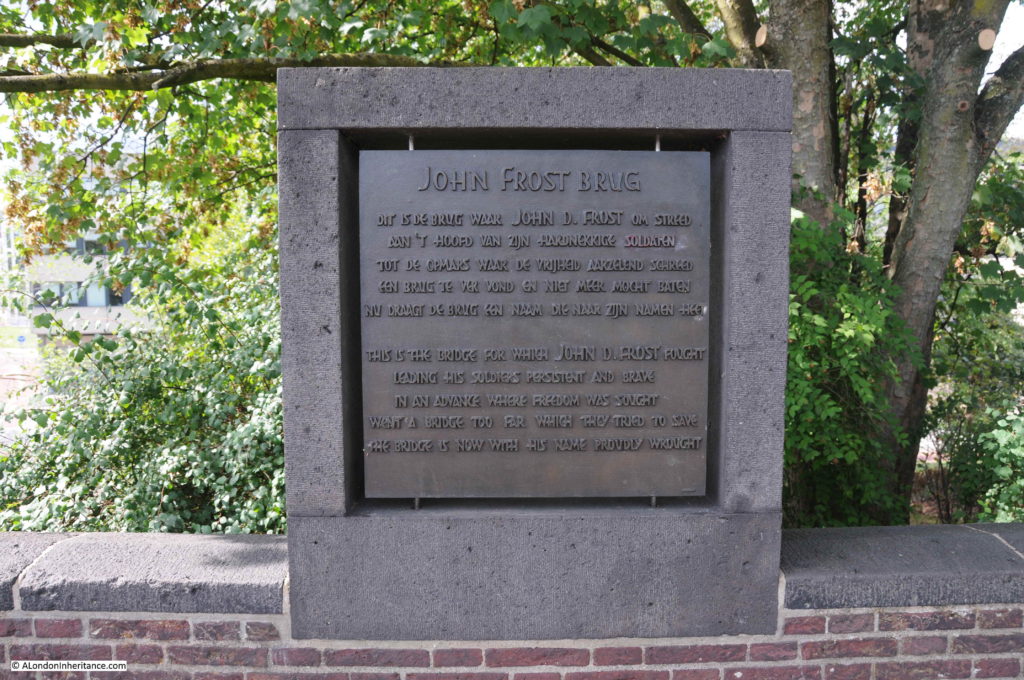

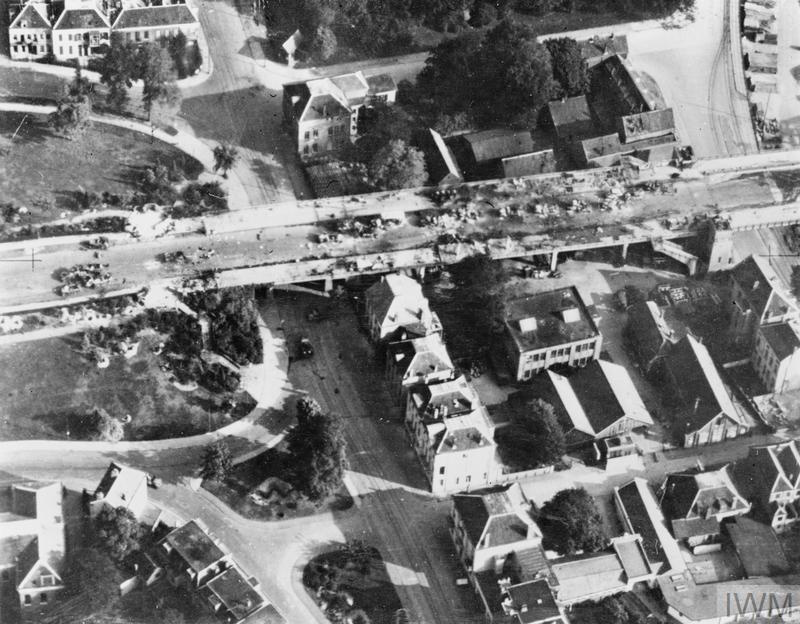

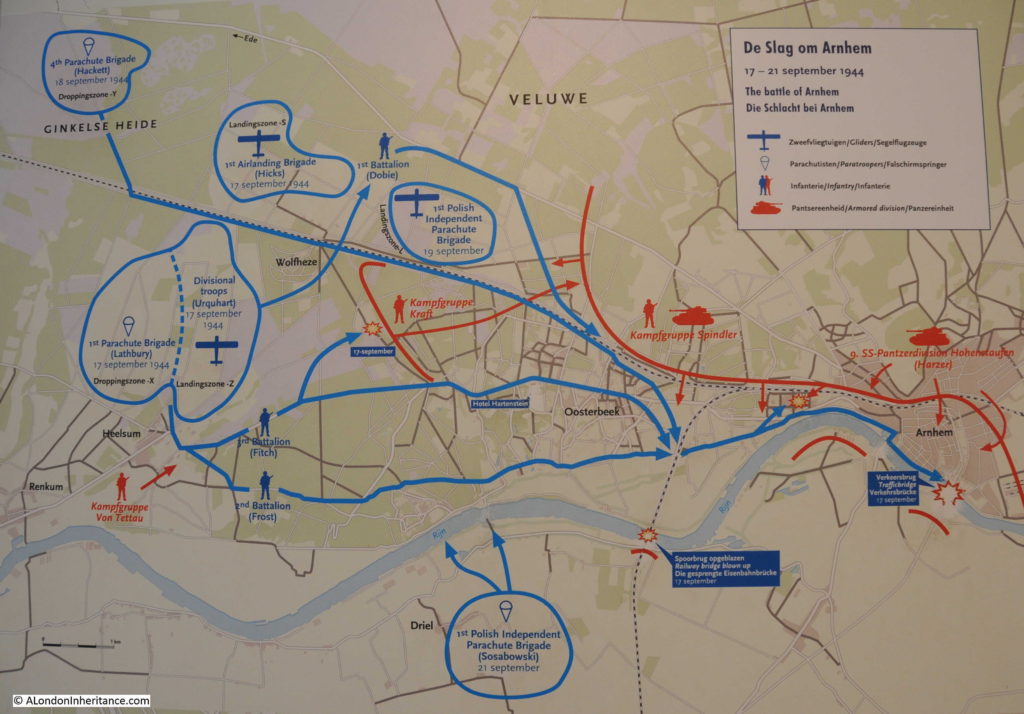

On the 17th September, eight aircraft from Harwell were detailed, as part of a much larger force, to tow Horsa gliders from Harwell to Arnhem. The gliders were carrying the HQ Staff and others from the First Airborne Division. One aircraft crashed on take-off. The remaining aircraft flew in loose pairs in a line astern formation. The trip out was at 2500ft, releasing the gliders over the drop zone at Grave, Holland, and then back at 7000ft. The chalk number of the glider was 504 belonging to 1st Airlanding Light Regiment, delivering them to landing zone Z. Enemy opposition was light and the weather fair. The only problem was with the planning, it was believed, wrongly as it turned out, that the drop of sufficient troops to capture Arnhem and its bridge could not be achieved in one day, and it was therefore split over two days, losing the element of speed and surprise. As a consequence the paratroops became heavily pinned down, and the rest has now become the sad but heroic history of Arnhem.

The 18th September saw phase two, the continued re-supply, 15 aircraft from 570 Sqn each containing 24 containers and four packages were detailed to re-supply the troops on the ground at Arnhem. The run to the drop zone was carried out at 1500ft, descending to 600ft for the actual supply drop. One aircraft failed to return, another was badly hit by flak over the Dutch Islands and made a successful crash landing. Enemy opposition was getting heavier with most aircraft suffering some flak damage.

View of Horsa Glider being towed:

View of the landing ground to the north west of Arnhem showing gliders scattered over the landing field:

By the 19th September the position of the troops on the ground was getting desperate. The part time German troops that were originally believed to be in the area turned out to be a crack Panzer division on rest leave. The British Paratroops were out-gunned and outnumbered, and were being squeezed into an ever smaller enclave. Food and ammunition were running low and it was clear that the objective of capturing the bridge over the Rhine would not be achieved. The troops were now fighting for their survival. For the third day running 570 Sqn were detailed to fly to Arnhem, 17 aircraft each carrying 24 containers and four packages were briefed to drop on the ever decreasing area occupied by the British troops. The weather was bad over Belgium and Holland with 10/10ths cloud and visibility in most areas down to 2-4000yds. This restricted fighter support as most of the continental airfields were closed. Enemy opposition had greatly increased, especially around the D.Z. area, and crews reported intensive 88mm flak most aircraft suffering casualties and damage. All dropped successfully but three aircraft failed to return to base from 570 Sqn which was doubly hard as it was subsequently learned that the British were no longer in the Drop Zone, having been beaten back into an ever diminishing area by overwhelming fire power.

The adverse weather prevented flying on the 20th. It was 55 years later, sitting in the Oosterbeek Cemetery in September 1999, the 55th Anniversary Commemoration of the Arnhem landings that I realised Dick and his crew had tried to fly on the 21st. It is not shown in his log book as they probably did not have time to keep the books up to date, but the Squadron records show that they took to the air once again but had to turn back after an hour with engine problems – perhaps as a result of flying lead on the last trip – we shall never know.

Dick and his crew were again in the air on 23rd, taking-off at 14.34. Because of the desperate position our troops were now in the drop was ordered at zero feet to try and ensure the supplies got through. At this height aircraft and crew become very vulnerable. Little did the rear gunner, Dennis Blencowe know that a distant relative, George Blinko who was with the 21st Independent Parachute Regt. was one of those fighting below. He was wounded and on his way to hospital in Oosterbeek and ultimately to a German POW camp. George never knew of their efforts but I’m sure he would have been amazed to know a distant cousin was fighting for him in the skies above.

Fighter support was again poor and the usual 88mm flak came up in large quantities. All aircraft were believed to have dropped their supplies, but four failed to return home – including Stirling EF298 V8-T which carried Dick Bond and his crew, plus two Royal Army Service Corps dispatchers who were pushing the supplies from the aircraft.

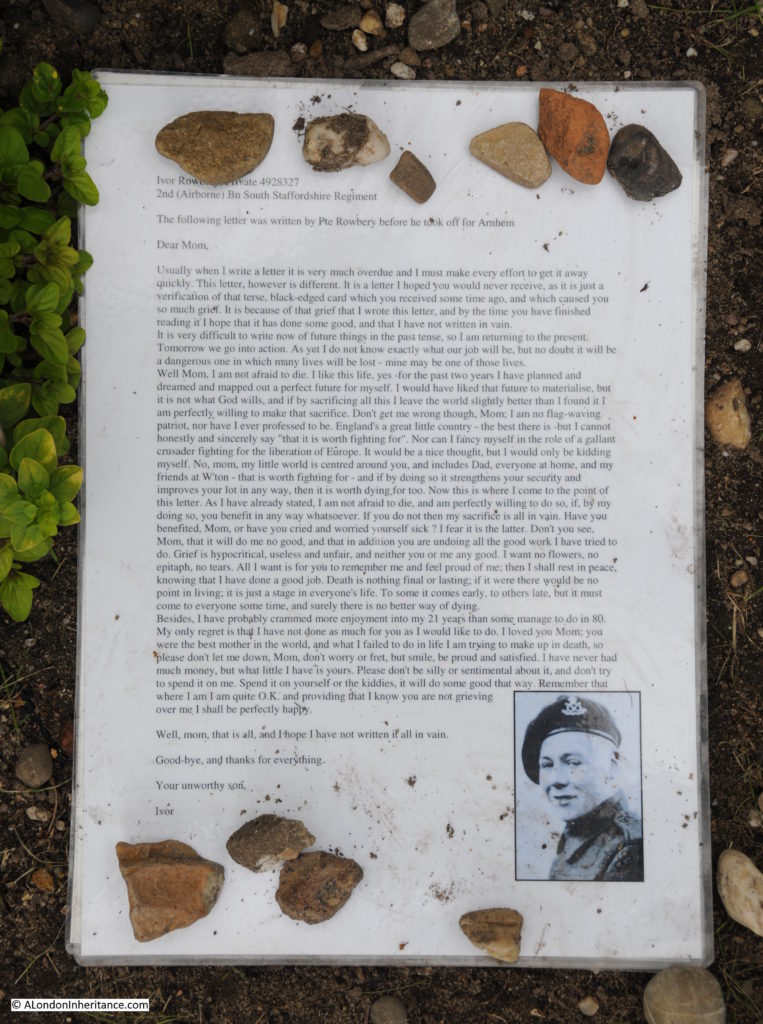

THE CREW OF STIRLING EF 298 V8-T

- Pilot F/O William Baker (RCAF)

- Air Gunner F/Sgt Dennis James Blencowe

- Flight Engineer Sgt Richard Bert Bond

- Air Bomber F/O Robert Carter Booth

- Navigator F/O John Dickson DFM

- Wireless Operator P/O Francis George Totterdell

- RASC dispatchers – Robert William Hayton & Reginald Shore

Robert William Hayton:

The time of qualifying as a Flight Engineer to the time of his death was only 10 months. He had flown a total of 121 hours daylight and 110 night. He was 24, leaving a wife and baby daughter.

Postscript

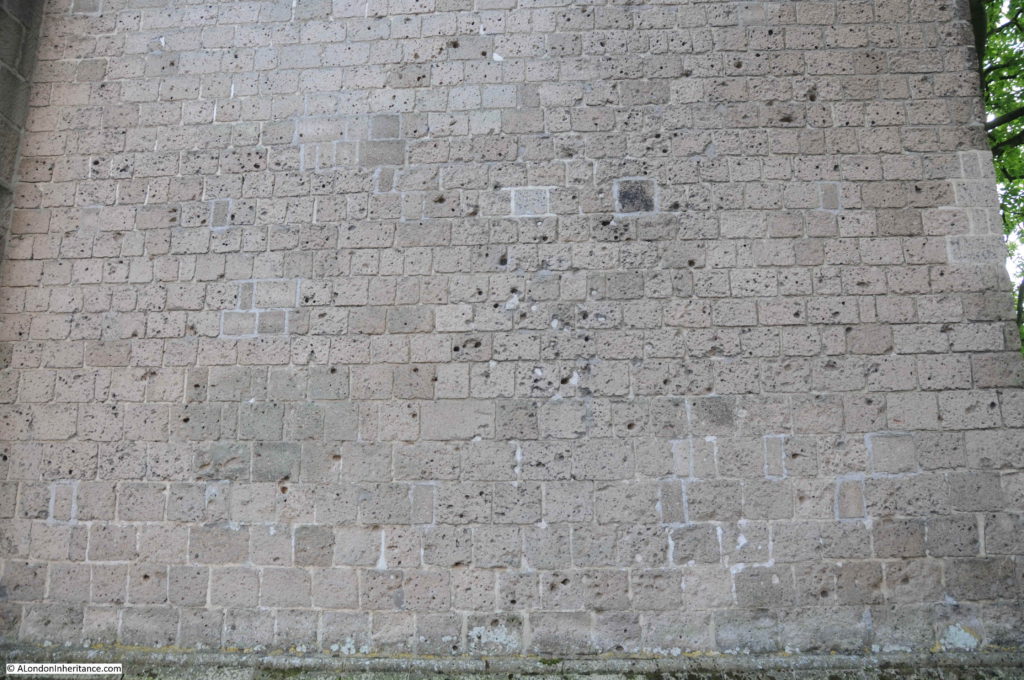

As I mentioned earlier, much of the above information has only come to light during my research since 1994. Dick and Stan’s 3 sisters and one brother, together with Dick’s wife and daughter have only learned recently what quiet heroes these young lads were. In 1994, the 50th Anniversary of Arnhem I visited the town and saw where the fighting took place. Although some 90 aircraft were lost in total, I managed to locate the crash site of Dick’s aircraft, deep in pine woods some 5 miles to the North-West of Arnhem – they had evidently dropped their supplies and were on their way home. The crash site was very much like Stan’s – a peaceful pine forest, but still with broken pieces of aircraft clearly visibly across a wide area. Again, I had an unbelievable stroke of good fortune. The owner of the woods produced two photographs taken of the crashed aircraft and kindly provided copies for me. To be able to actually see the crashed aircraft 50 years later was remarkable.

Pictures courtesy of Mr Koker, the land owner:

Aerial photo taken 3 months later 23rd Dec 1944. The crash site is the rectangular shape in the centre of the picture, to the left of the road and railway line. The Germans collected the metal to recycle.

Although there are memorial stones in the Arnhem cemetery to all the crew of six plus the two Army Air Corps dispatchers who were pushing the supplies out of the aircraft, it was known that only three bodies were actually found. Our family have always believed for the last 50 years that Dick was literally blown to pieces. Although his wife has visited the gravestone, she felt that this had little meaning as “Dick was not there”. After my return to England I received a letter from the Dutch man who owned the woods. He had found a negative and had it developed. It showed two crosses. Of the eight people on board, three bodies had been found and buried alongside the plane. Of these three bodies the picture only showed two crosses. On one of the two crosses it is possible to make out on the original enlargement the words “An unknown British Airman”. On the other is my Uncle’s name –R.B. BOND

My Aunt (Dick’s wife) and her daughter went back to Arnhem in September 1994 for the 50th Anniversary Commemorations. For my Aunt, it was to say a final Goodbye to her husband after 50 years. For her daughter, it was to say Hello to the Father she never knew.

In October 2002 Aunt Jessie died. It was Dick’s daughter’s wish that her mum’s ashes would be buried at her father’s grave in Arnhem. Re-united at last.

The Commonwealth War Graves Commission advise that Robert Hayton was found in or near the aircraft and given a field burial by local Air Raid Wardens in the Onder de Bomen General Cemetery Renkum and was re-interred to Arnhem Oosterbeek War Cemetery on 22 August 1945.

The CWGC advise that Dispatcher Shore’s unidentified body was initially buried by the crashed plane in the wood and was subsequently moved to Arnhem in March 1946. He was later identified in 1987 as the other members of the aircraft had been positively identified.

This report is my small tribute to the brave young men who gave their lives for our freedom

Headstones of the Aircrew Baker, Blencowe, Bond, Booth, Dickson & Totterdell

Oosterbeek Commonwealth War Graves Cemetery

Headstones of the RASC Army Dispatchers Hayton & Shore

I am really grateful to Paul for telling the remarkable story of those named on the temporary grave marker in my father’s photo, and for letting me publish it on the blog. If anyone has any additional information, or are relatives of the other aircrew, Paul can be contacted on: