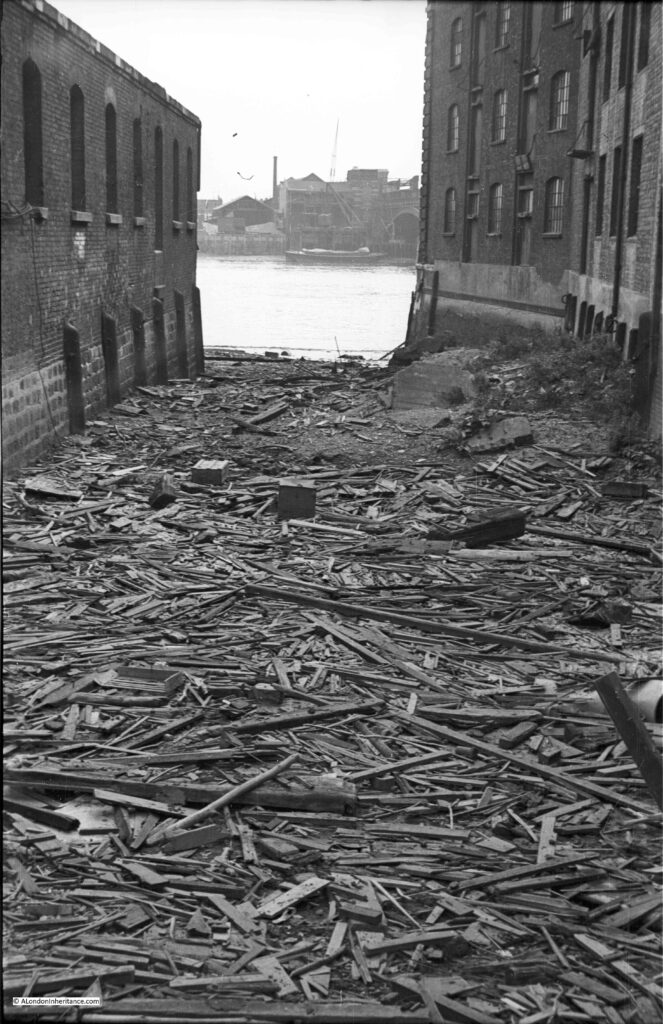

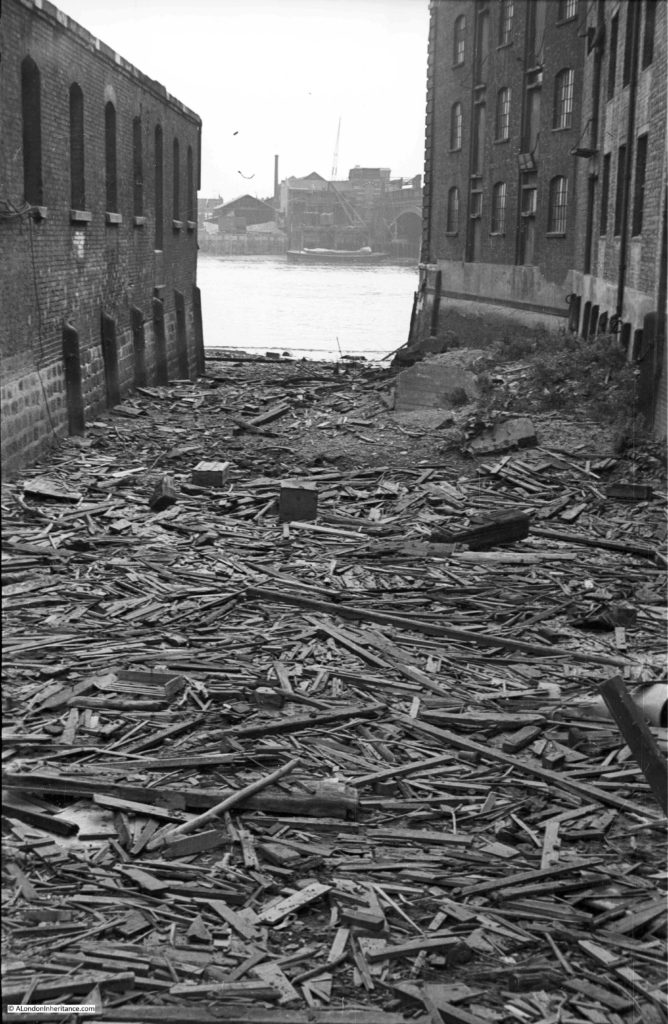

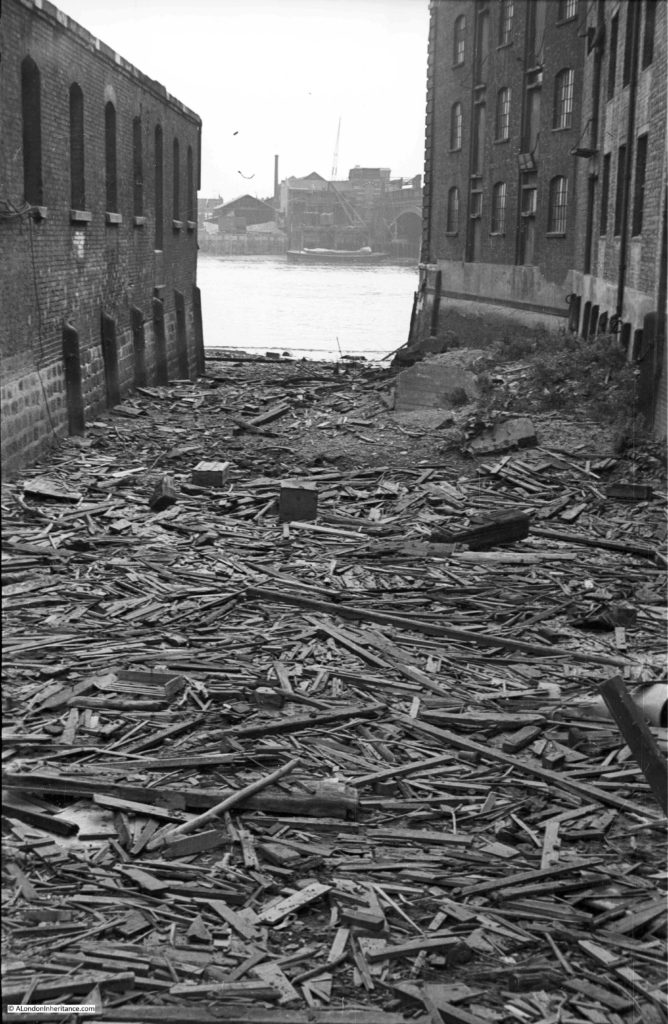

Puddle Dock is a location that today, is a short street between Queen Victoria Street and Upper Thames Street, but for centuries was one of the large inlets along the river in the City that provided a dock for shipping. The photo below was taken by my father in 1947. I was originally unsure of the location as there is very little in the photo to identify the location today. The Thames is an obvious clue, but what confirmed this to be the original Puddle Dock is the short part of a bridge, seen to the right of the photo on the opposite bank of the river, along with the alignment of the dock and the length of the buildings on either side. All this I will explain below.

Firstly, the bridge across the river. This is the railway bridge across the river into Blackfriars Station. It is almost impossible to take a photo from the exact location as my father, however in the photo below I am standing in the middle of Puddle Dock and the bridge can be seen on the right with the arch on the opposite bank of the river in roughly the right position.

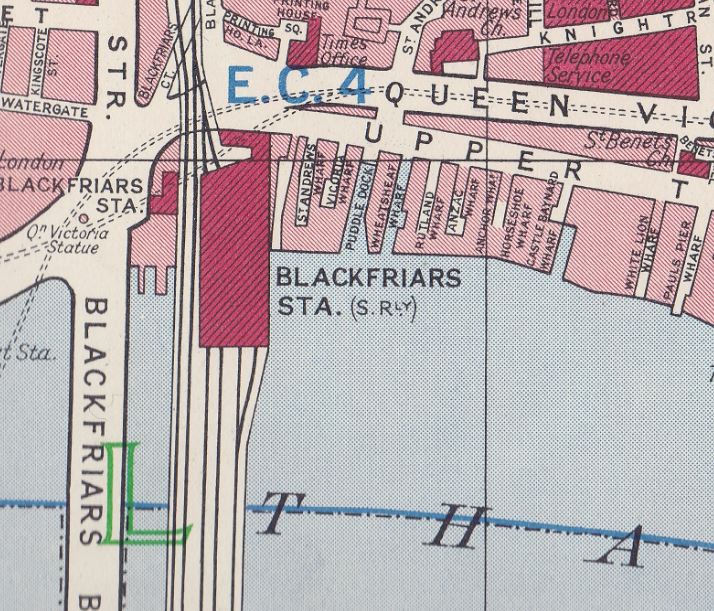

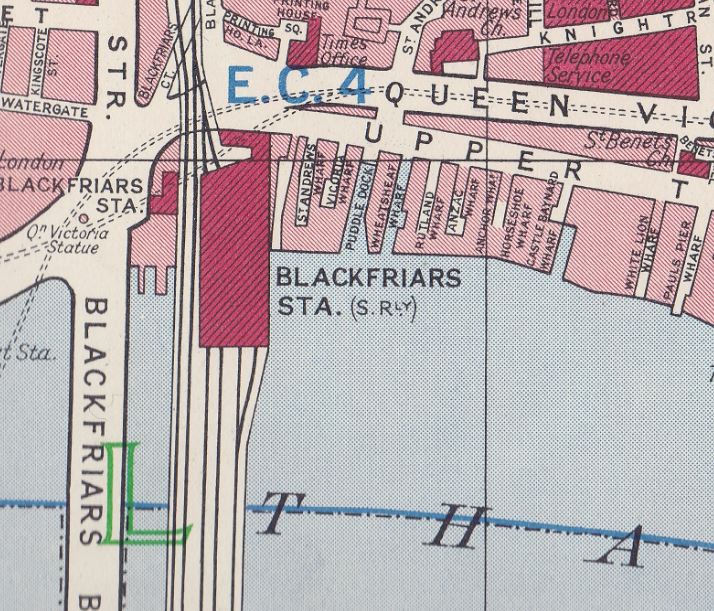

My next step in confirming this to be Puddle Dock was to check the map in the 1940 edition of Bartholomew’s Reference Atlas of Greater London. The extract from the map is shown below with Puddle Dock in the centre of the map, just to the right of Blackfriars Station.

In the 1940 map, the dock is angled towards the bridge, and the building on the right of the dock angles inwards halfway down in such as way that it would appear to be a shorter building to that on the left. This is exactly as the buildings appear in the 1947 photo, although the key point is that the right and left are transposed in the photo as it was taken looking out from the dock.

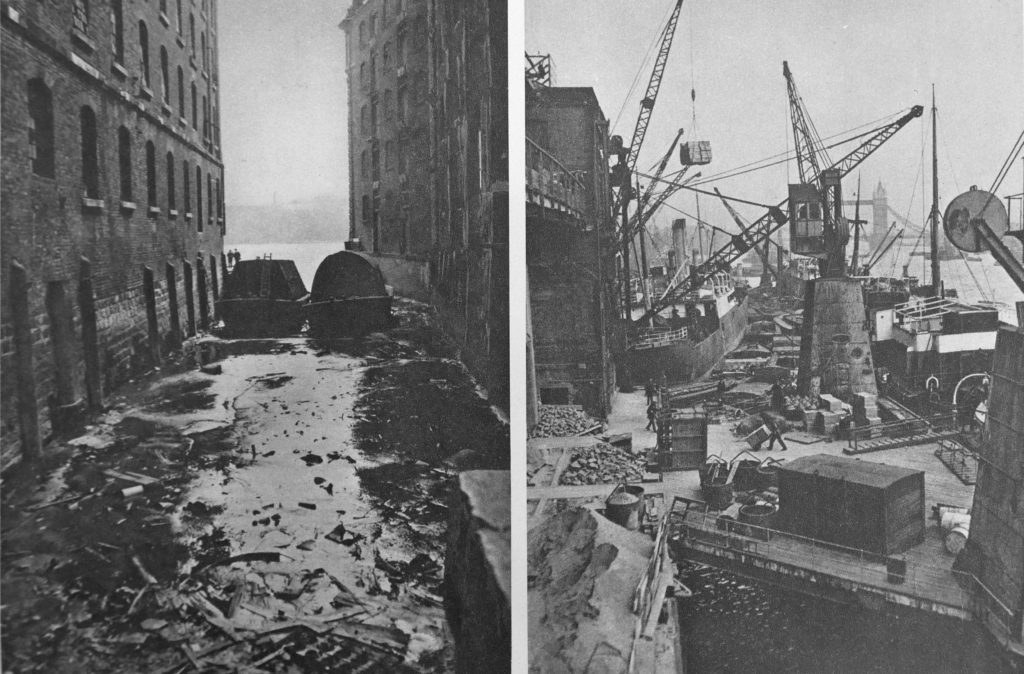

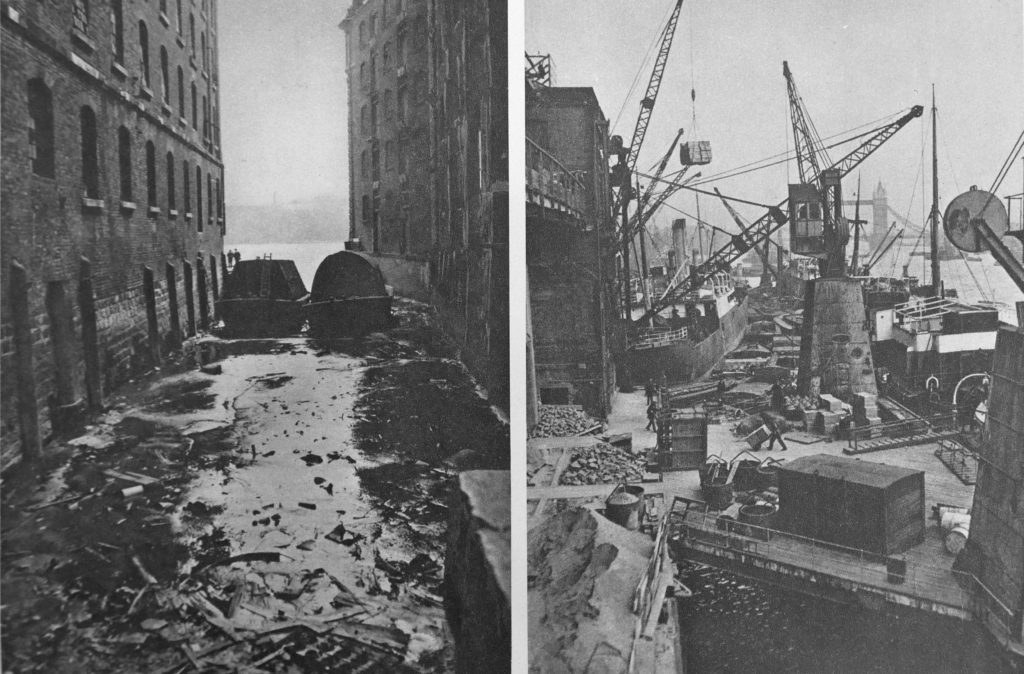

I am confident therefore that the 1947 photo is of Puddle Dock. I did check the London Metropolitan Archive Collage collection, but could not find any photos of Puddle Dock so they may be few and far between. When finishing off this post, I did find one photo of Puddle Dock in volume one of Wonderful London published in 1926 / 1927. The photo is shown below on the left:

Compared to my father’s photo, the building on the left had lost its upper floors by 1947, probably as a result of wartime bomb damage. Even by 1926 Puddle Dock was viewed as a remnant from the past. In Wonderful London, the text below the two photos reads:

“Dramatic Contrast: Old Puddle Dock Lonely And Dirty And Modern Wharves Crowded And Clean – By comparing these two photographs we can appreciate the growth of London’s commerce. in other days we should have found Puddle Dock, which is seen in the left-hand photograph crowded with lighters from ketch and galliot unloading their cargoes laboriously by hand. Now it is frequented only by dingy barges; while it makes a useful rubbish-heap for the neighbourhood. Apart from its narrowness, Puddle Dock could not be visited by great steamers, since it is near Blackfriars Bridge, and only a few large ships, specially constructed, come farther up the Thames than London Bridge. In the photograph on the right we look down the river from London Bridge. The fruit wharves are in the foreground, where trim freighters are being unloaded by cranes.”

In the 1947 photo Puddle Dock is strewn with rubbish, although I doubt Londoners were still dumping their rubbish at the dock, probably rubbish washed in at high tide. In the immediate post war years there was still lots of debris along the river edge from the bombed buildings along the Thames.

Puddle Dock today is the name of the street that runs down from Queen Victoria Street to Upper Thames Street and there are plenty of name plaques to hint at the original use of this area of land running down to the River Thames.

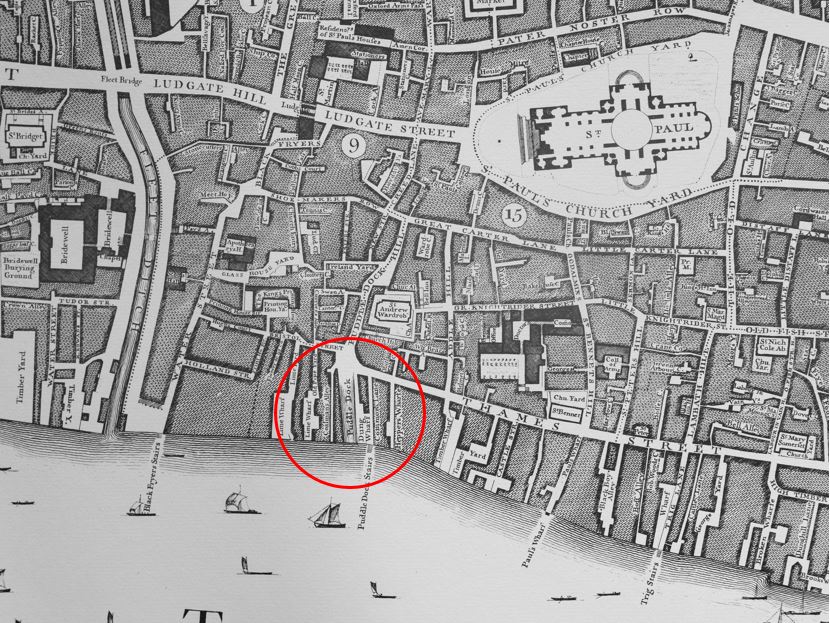

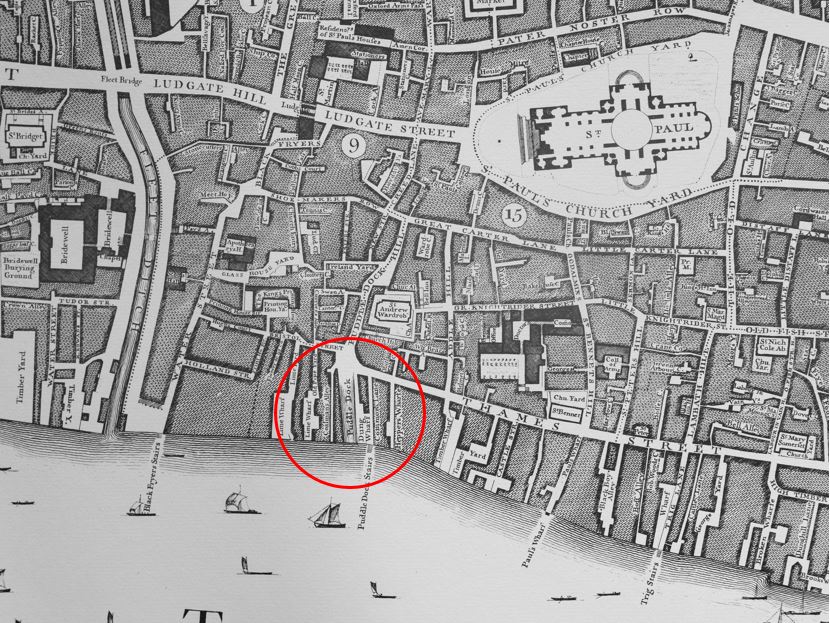

Puddle Dock has a long history. John Rocque’s map of 1746 shows the dock (circled in the extract below) as a large dock with the same width onto the river as the Fleet Ditch on the left. The way the shading is drawn probably indicates a sloping dock from the river up to Thames Street, very much like the 1947 photo.

For the last 300 years, newspapers contain many references to Puddle Dock. One article can be directly linked to the map above. If you look at the end of the dock, on the right it is labelled “Dung Wharf”. An article in the Evening Mail on the 25th November 1836 covered a legal case “The King v. Gore” which goes some way to explaining the name and purpose of Dung Wharf:

“This defendant has been indicted for a nuisance in keeping a quantity of filth and dirt at Puddle-dock. He has moved the proceedings into this court, and then suffered judgement by default. He was now brought up to receive the judgement of the Court.

The affidavits of several persons residing near Puddle-dock were read, in which they stated that their health was impaired in consequence of the stench arising from the filth which was allowed to accumulate at this dock.

The defendant then put in an affidavit, stating that he had become a tenant to the corporation of London of the laystall at Puddle-dock; that he was obliged, by the covenant in his lease, to allow all persons to place any filth they chose there; that he was not allowed by his lease to suffer more than five barge loads to remain there at any one time, and that he had never done so; and that this had been a laystall ever since the great fire of London. He admitted that it was a nuisance to the surrounding neighbourhood, but that it could not be avoided.

The Attorney-General, for the prosecutors, said their Lordships would see it was necessary that the prosecution should be adopted. The inquest of the ward had made a presentment, and the Court of Alderman had no choice. They did not indict him for keeping a laystall, because that was authorised by act of Parliament. There were three in the city, Puddle-dock, Dowgate, and Whitefriars. With respect to the latter there had never been any complaint; but thank God, he did not live near Puddle-dock, for if he did he should have reason to complain. All the deponents to the affidavits had sworn that they suffered great inconvenience. It was not for keeping a laystall, but for the manner of keeping it, that the defendant was indicted. Mr. Gore had brought the filth from Covent-garden Market, even on Sundays. He said he must mix some vegetables up with the other filth. All the City wanted was, that the Court would pronounce such a sentence as would prevent the repetition of this mischief.”

The court case does not seem to have made any progress, as at the end of the article it states that “After a good deal of discussion, it was directed that the judgement should be suspended with leave to file fresh affidavits.”

The term “laystall” referenced to in the article is a place where “waste and dung” are deposited. The five barges at Puddle Dock obviously taking away the city’s waste and dumping somewhere down river. It must have been a horrible place to be in the summer and it is easy to understand the impact that the laystall had on nearby residents.

William Maitland writing in The History of London in 1756 states: “On the Banks of the River Thames are the Wharfs of Puddle-dock, used for a Laystall for the Soil of the Streets, and much frequented by Barges and Lighters for taking the same away, as also for landing of Corn and other Goods.”

Most written references to poor Puddle Dock I have seen associate the location with rubbish and filth.

The earliest newspaper article referencing Puddle Dock was from the 5th July 1722 which highlights both the graphic reporting of the time and just how dangerous it was on London streets:

“Another Misfortune happened Yesterday at Puddle-Dock, where a little Boy was killed by a Cart loaded with coals. The Child was stooping down to take up some thing from the Ground when the Cart Wheel ran over his head, and crushed it to Pieces. The Carman is absconded”

The origin of the name Puddle Dock can be found in Stow’s Survey of London from the 1603 edition where he writes: “Then is there a great Brewhouse, and Puddle wharfe, a water gate into the Thames, where horses use to be watered and therefore filed with their trampeling, and made puddle, like as also of one Puddle dwelling there: it is called Puddle Wharfe.”

The name “Puddle” is therefore from at least the 16th century and pre-dates the Great Fire of London. I have not had the time to find how far further back the name was in use – one of the ever-expanding list of things to check.

Puddle Dock today is rather a sterile place, however reading what has happened here in 300 years of newspaper reports really does bring home that for centuries this was a place of work, where people lived and where life in general played out between the City and river.

Tangible evidence of those who have worked around Puddle Wharf can be found in the trade tokens issued by businesses in the area. The British Museum has a collection of these tokens and the following is one issued by Thomas Guy at Puddle Wharf in 1668 (©Trustees of the British Museum):

In the decades after my father took the photo of Puddle Dock, the area has changed dramatically. The old dock was filled in, the Mermaid Theatre was built on the eastern edge of the dock, the river embankment was extended into the river and Upper Thames Street was rerouted to pass under Blackfriars Station to provide a direct link with the Victoria Embankment. See my post about the lost road junction between Queen Victoria Street and Upper Thames Street for more photos and history of the area.

The photo below is looking up from the river’s edge into what was Puddle Dock:

It is easy to walk past Puddle Dock. There are few reasons to walk along the street today, it is mainly a convenient route for traffic between Queen Victoria and Upper Thames Streets, but at least the name remains. One positive point is that despite the pollution from traffic along the streets on either end of Puddle Dock, it probably does smell far better than it has done for many centuries, when Londoners would have piled up their waste and filth at the laystall ready for disposal along the river.

alondoninheritance.com