London today is covered by streets, pavements and buildings. Apart from the larger parks, there are a limited number of small green spaces. So much of what shaped the surface has been long hidden, but we can still find signs as to why the built environment appears as it does, and how names recall features we cannot see.

Clerkenwell, up to the Angel has been shaped by water. The River Fleet created much of the western boundary. New River Head was built at a point which was almost at the same 100m contour that followed the river back to the springs in Hertfordshire, the fall in height to the City and Thames provided a distribution system using gravity.

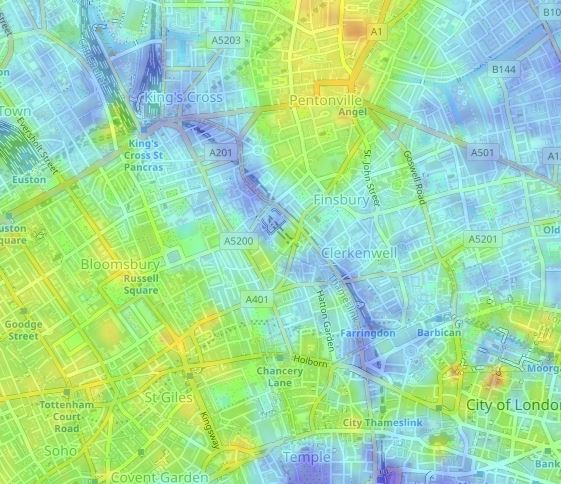

We can see this by overlaying an elevation map on top of a street map. In the following extract, dark blues are lowest height, with the colours changing up to red as height increases (map from topographic-map.com)

We can see the dark blues of the River Fleet valley. As elevation increases the map shades through green then orange and red as the height increases up to north Clerkenwell, Finsbury and the Angel at the top centre of the map.

Much of this area had numerous springs and wells, and as the land increased in height, it passed through bands of London Clay and gravel, and it is a band of gravel and a well that gave rise to the location of today’s post – Sadler’s Wells.

Sadler’s Wells is a world leading theatre and centre of dance, located at the northern end of Rosebery Avenue. There has been a theatre on the site for many centuries, the current building opened in 1998, photographed below looking north along Rosebery Avenue with Arlington Way on the left.

William J. Pinks in the History of Clerkenwell (1865) describes the origins of Sadler’s Wells: “This popular place of amusement is the oldest theatre in London. Some time before the year 1683 a wooden building, called Sadler’s Music House, stood on the north side of the New River about this spot. Sadler, as well as being the proprietor of this establishment, was a surveyor of the highways. In the year last mentioned, his servants, while digging in the garden for gravel, discovered a well of mineral water, which shortly afterwards became very celebrated for its curative properties; so that it was visited by five or six hundred people every morning”.

The well that Edward Sadler’s workmen had discovered possibly dated from the 12th century or earlier when many of the wells in Clerkenwell were used by the Clerkenwell priory to persuade people that the virtue of the waters came from the strength of their prayers. (Books have different accounts of Sadler’s first name, with Richard or Dick being frequent references, however the Survey of London concludes Edward as being the almost certain name, based on a Chancery Court proceeding against him. Edward Sadler was a vintner, who in 1671 had taken a 35 year lease on the area that would become Sadler’s Wells).

The wells were closed at the reformation as they were claimed to support a superstitious believe in the power of the waters.

Pinks provides some additional description of the well found by the workmen: “When they had dug pretty deep, one of them found his pick axe handle strike upon something that was very hard, whereupon he endeavoured to break it, but could not,; whereupon, thinking within himself that it might, peradventure, be some treasure hid there, he uncovered it very carefully, and found it to be a broad flat stone, which having loosed and lifted up, he saw it was supported by four oaken posts, and under it a large well of stone arched over, and curiously carved”.

Sadler capitalised on the discovery of the well, and quickly promoted the health benefits of the waters, and as Pinks described, the wells were soon visited by several hundred people a day. Sadler encouraged the regular drinking of the waters, and put on several forms of entertainment to encourage people to come, stay, and spend money. Treatment included recommendations to stay at the well for a whole day, drinking the waters at specified times, walking and resting around the surrounding gardens in between drinking sessions.

Sadler and the well that his workmen discovered would provide the name for the site, and most histories seem to put the discovery of the well as the starting point for the following centuries of the site as a place of entertainment, however Pinks provides a hint that it was probably providing such a function for many years prior to 1683:

“A petition from the proprietor of Sadler’s Wells to the House of Commons, stating that the site was a place of public entertainment in the reign of Queen Elizabeth. If this be correct, Sadler was certainly not its first possessor for musical purposes and water drinking”.

It appears that Sadler was not running the site for too many years after discovery of the well, and the popularity of the well would also quickly decline. In the 1690’s the well appears to have been closed, but by June 1697 the following advert would appear in the ‘Post Boy’:

“Sadler’s excellent Steel Waters, at Islington, having been obstructed for some years past, are now opened and current again, and the waters are found to be in their full vigour, strength and virtue, as ever they were, as is attested and assured by the physicians who have since fully tried them”.

By 1699 the building occupying the site was called Miles’s Music House, and entertainment, rather than the waters seems to have been the main focus.

The following photo was taken a little further south along Rosebery Avenue and shows how close Sadler’s Wells is to New River Head which is on the left, with the curved Laboratory Building on the left of the theatre.

Today, Sadler’s Wells is in the heart of north Clerkenwell / Islington. A short distance south from the busy junction at the Angel, however the theatre has its origins when the area was still rural.

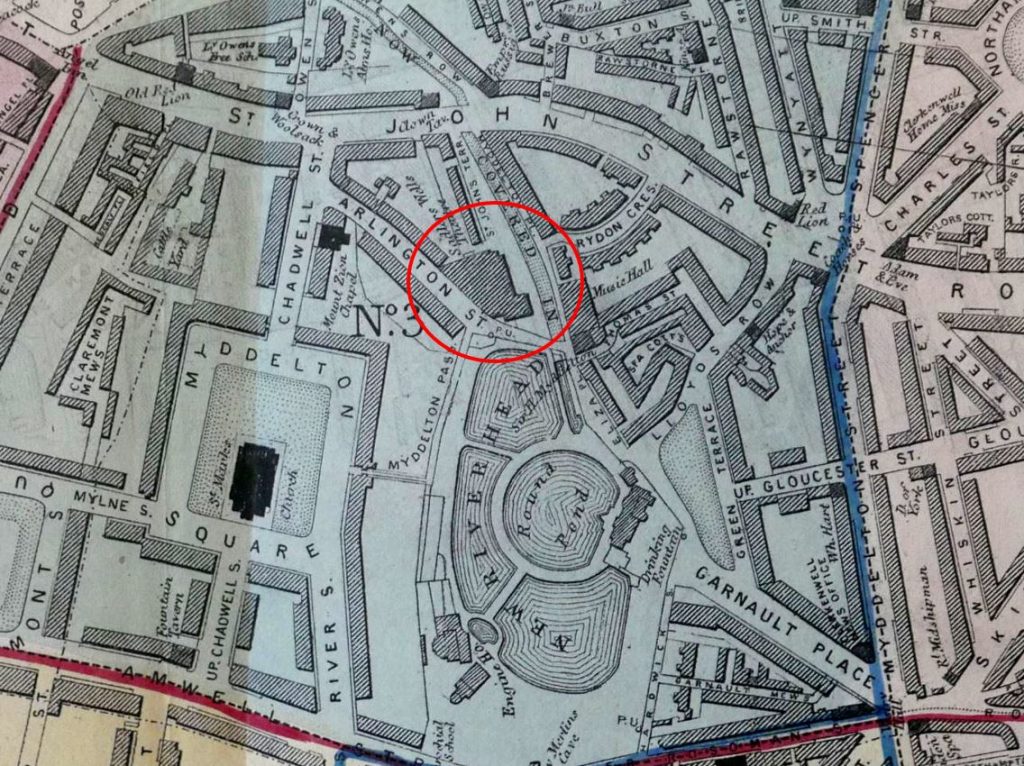

In the following extract from Rocque’s 1746 map, I have circled the location of Sadler’s Wells.

The rectangular shape in the upper part of the circle is presumably the theatre, surrounded by gardens. Note the New River coming in from top right down to the round pond of New River Head to the left of Sadler’s Wells. The New River would form a southern border for the site for many years. The River Fleet is on the left of the map, running between the lines that indicate sloping land forming the valley of the river – exactly as we can see today on the elevation map, and when walking the streets.

The map also shows that in 1746, over 60 years since the discovery of the well, Sadler’s Wells was still surrounded by fields.

At night, the area between Sadler’s Wells and the City was a notorious area for thieves, and those heading back often risked their lives, as the following report from the Newcastle Courant in 1716 makes clear:

“On Saturday Night, a Gentlewoman, one Madam Napp, and her Son, betwixt 10 and 11 coming from Sadler’s Wells at Islington, where they have been to see the Diversion of Dancing, to their House in Warwick Court in Holburn; were attacked by some Foot Padders, on this Side of Gray’s Inn Garden Wall.

The Gentleman Collar’d one of them, and flung him down to the Ground, and whilst he was struggling with another, his Mother cryed out Murder; upon which the third Rogue fired a Pistol and shot her dead.

Some People at Bromley Street hearing the Pistol go off, ran to see what was the Matter, and the Roques scoured off, and had not Time to take any Thing from the Gentleman, but his Hat and Wigg. A Soldier, and two others, were seized on Suspicion of being the Rogues, and carried before Mr Plummer, a Justice of the Peace in Bedford Row, who committed them to Newgate”.

Not every attempted robbery ended with such fatal consequences, but judging by the number of newspaper reports, care needed to be taken when walking home at the end of an evening’s performance.

One hundred years later, and London had reached, and surrounded Sadler’s Wells as shown in the following extract from Reynolds’s Splendid New Map of London of 1847:

And for no other reason than I love maps, and will use any excuse to put one in a post, this is an extract from the large scale map of Clerkenwell in Pinks’ History of Clerkenwell, showing the location of Sadler’s Wells around 1860.

From Sadler’s original Music House, the buildings of Sadler’s Wells have been through many iterations with rebuilds and additions as the popularity of the site changed, along with the type of entertainments put on by the theatre.

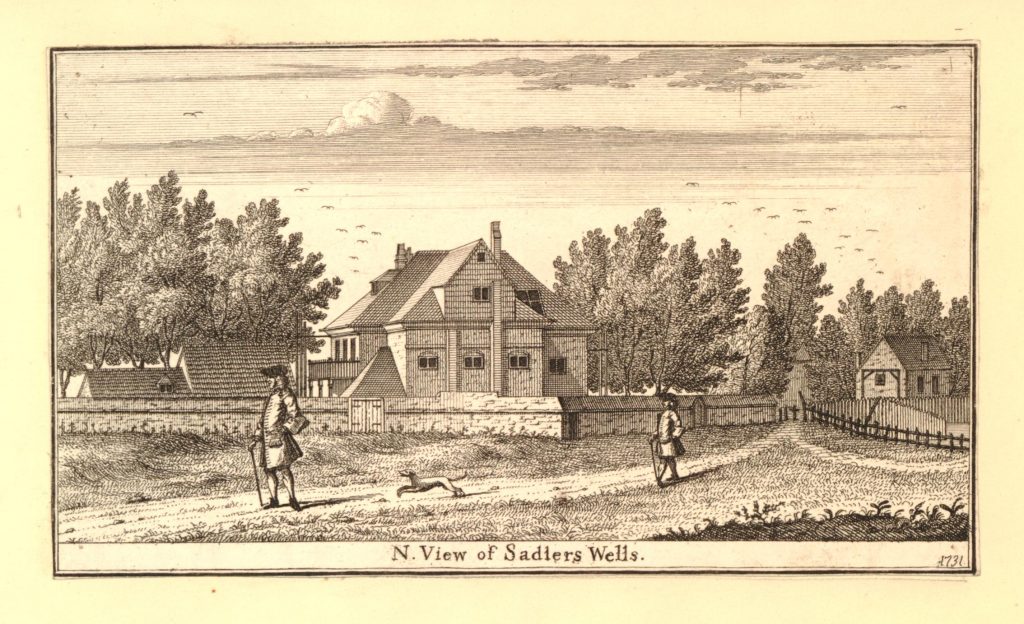

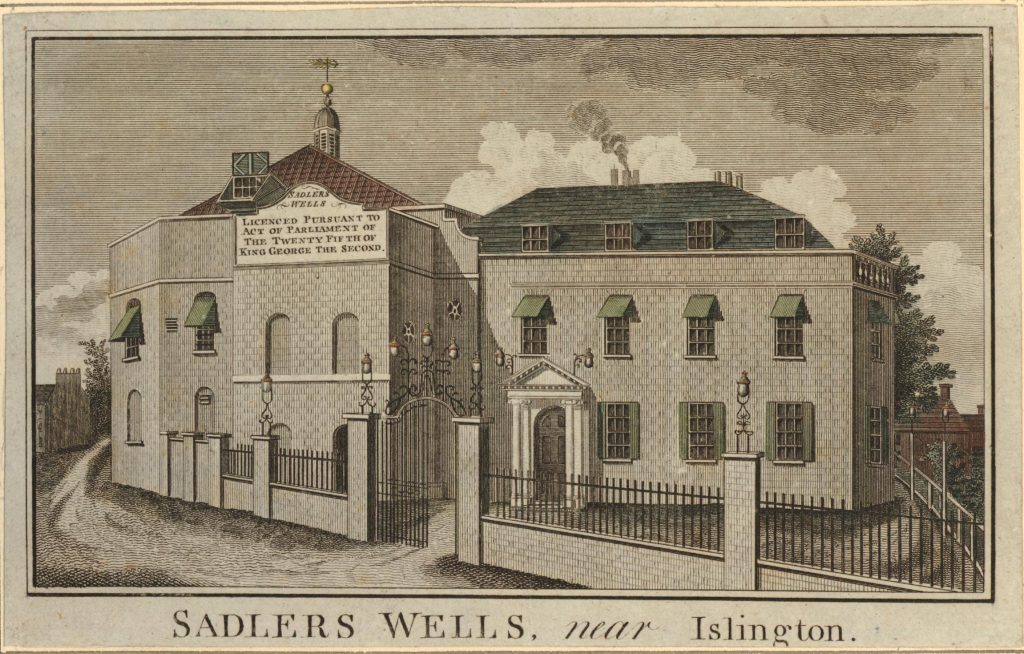

In 1731, 15 years before the Roque map, the following print shows Sadler’s Wells in a very rural location, the theatre surrounded by trees and a couple of out buildings.

Sadler’s Wells also featured in a 1738 print by Hogarth from his Four Times of Day series. In “Evening”, we see the entrance to Sadler’s Wells on the left, with the inn, the Sir Hugh Myddelton on the right. In the scene, a Dyer and his family are strolling over a footbridge by the New River.

The entertainments provided at Sadler’s Wells were many and varied. An advert from July 1740 stated that there would be “rope-dancing, tumbling, singing, and several new grand dances, both serious and comic. With a new entertainment called ‘The Birth of Venus’ or Harlequin Paris’. Concluding with ‘The Loves of Zephyrus and Flora’. The scenes, machines, dresses and music being entirely new”.

An advert from 1742, concluded with “Several extraordinary performances by M. Henderick Kerman, the famous ladder dancer”.

In the 1740s. Sadler’s Wells were described as a place of “great extravagance, luxury, idleness and ill fame”, and that there were frequently great numbers of loose, disorderly people.

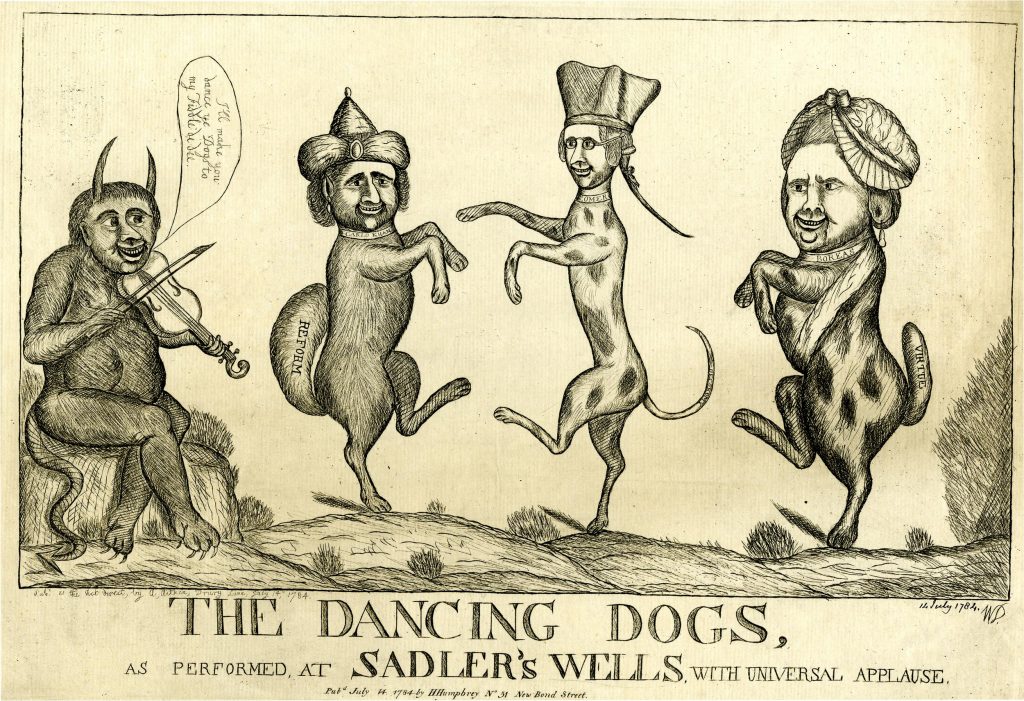

Probably because of the perception of Sadler’s Wells, it was included in a number of satirical prints of the time, including the following print from 1784:

The devil plays the violin whilst three dogs dance. Each dog has the head of a politician. The Whig politician Charles James Fox is on the left. Facing him is the Whig MP Edmund Burke, and on the right is Lord North, who had resigned as Prime Minister the previous year following a vote of no confidence after the loss of the American War of Independence.

Dancing dogs were indeed one of the 18th century forms of entertainment at Sadler’s Wells, and other forms of animal entertainment included a singing duck.

In the 18th century, theatres and plays needed to be licensed. The Licensing Act of 1737 theoretically prevented all theatres apart from the Royal Patent Theatres at Drury Lane, Covent Garden and Haymarket, from putting on drama without musical accompaniment. Many theatres did continue to put on productions, including Sadler’s Wells and the licence conditions do not seem to have been rigorously enforced. They were mainly meant to prevent anti-government propaganda, with plays having to be submitted for approval. Remarkably, this continued until 1968.

In 1790, Sadler’s Wells had a large sign on the side of the building indicating that the theatre was licensed.

There was tragedy at Sadler’s Wells in 1807, when eighteen people lost their lives and many more were badly injured. From a newspaper report of the time:

“DREADFUL ACCIDENT AT SADLER’S WELLS. On Thursday night, as the curtain was letting down at Sadler’s Wells theatre, to prepare for the water scene, in the Wood Daemon, a quarrel commenced in the pit, and some people cried out ‘A Fight’. The exclamation was mistaken for a cry of ‘Fire’. It was a benefit night and the house was crowded. Every part was immediately terror and confusion; the people in the gallery, pit and boxes, all pressed eagerly forward to the doors, but could not obtain egress in time to answer their impatience. The pressure was dreadful; those next to the avenues were thrown down and run over by those immediately behind, without distinction of age or sex. Of those quite in the rear some became desperate; they threw themselves from the gallery into the pit, and from the boxes onto the stage. A horrible discord of screams, oaths and exclamations reigned throughout. On the exterior of the theatre, the scene was not less dreadful; at every door and avenue might be seen people dragging out those persons whose strength was exhausted, and who were unable to effect their escape, but had just strength to gain the passage, or had been forced forward by the crowd behind. Not less than 50 women were fainting at the same time, on the inside and outside of the house”.

Of the 18 dead, there were seven men, seven women, three boys and one girl. Two men suspected of causing the initial commotion were taken to Clerkenwell Bridewell and brought before a judge, however he directed the jury that they could not be found guilty of murder or manslaughter, and that the eighteen met their deaths “Casually, accidentally and by misfortune”.

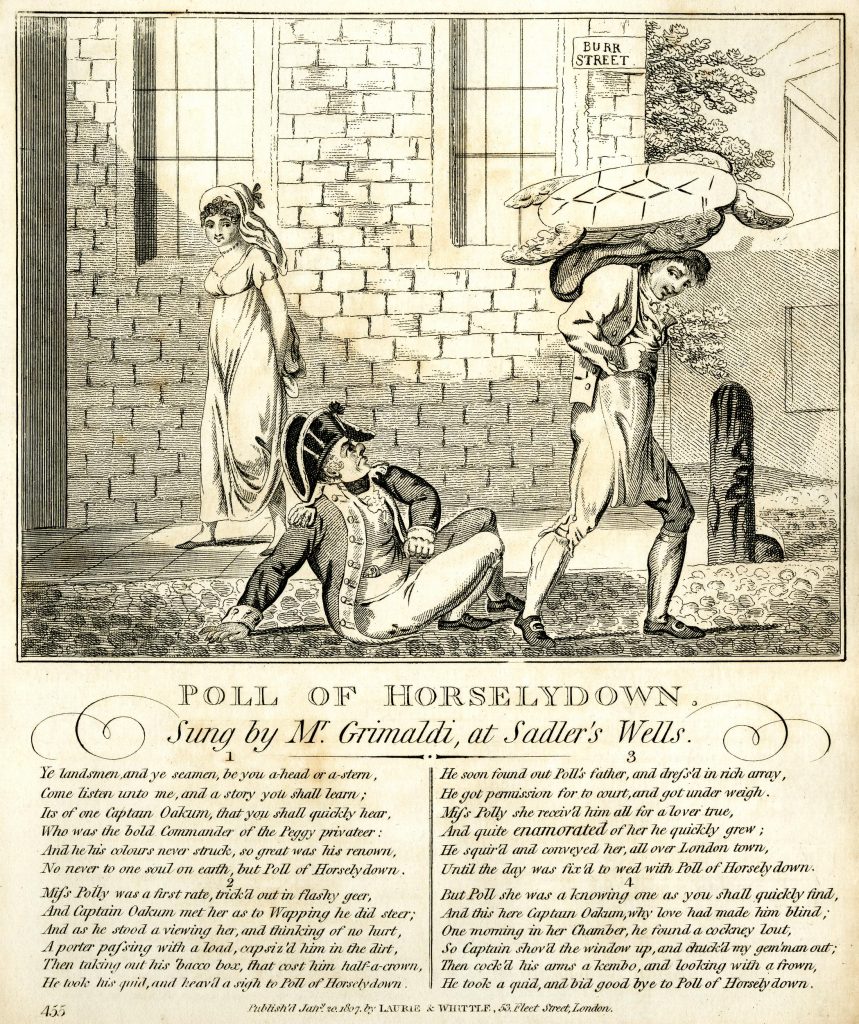

On a happier note, the first couple of decades of the 19th century were when the actor, comedian and dancer, Joseph Grimaldi was one of the leading attractions of Sadler’s Wells, and also recognised as one of London theatres leading clowns.

Grimaldi appeared at Covent Garden, Drury Lane and Sadler’s Wells theatres, but appears to have been more successful at the Islington venue. In 1812 he earned £8 a week at Covent Garden and £12 a week at Sadler’s Wells.

It was common at the time to publish the songs from well known entertainers such as Grimaldi, along with a suitable drawing portraying the theme of the song. One of those sung by Joseph Grimaldi at Sadler’s Wells in 1807 was Poll of Horselydown:

Also in the early years of the 19th century, Sadler’s Wells made use of the theatres proximity to the New River. Pinks writes that “An immense tank was constructed under the stage, and extending beyond it, which was filled by a communication with the New River, and emptied again at pleasure. On this aquatic stage, the boards being removed, was given a mimic representation of the Siege of Gibraltar, in which real vessels of considerable size, bombarded the fortress, but were subdued by the garrison, and several of them in appearance burnt”.

The Aquatic Theatre as such performances were known added another novel element to the performances at Sadler’s Wells. The following ticket was for a box on Monday 22nd September 1817 to watch one of the aquatic performances.

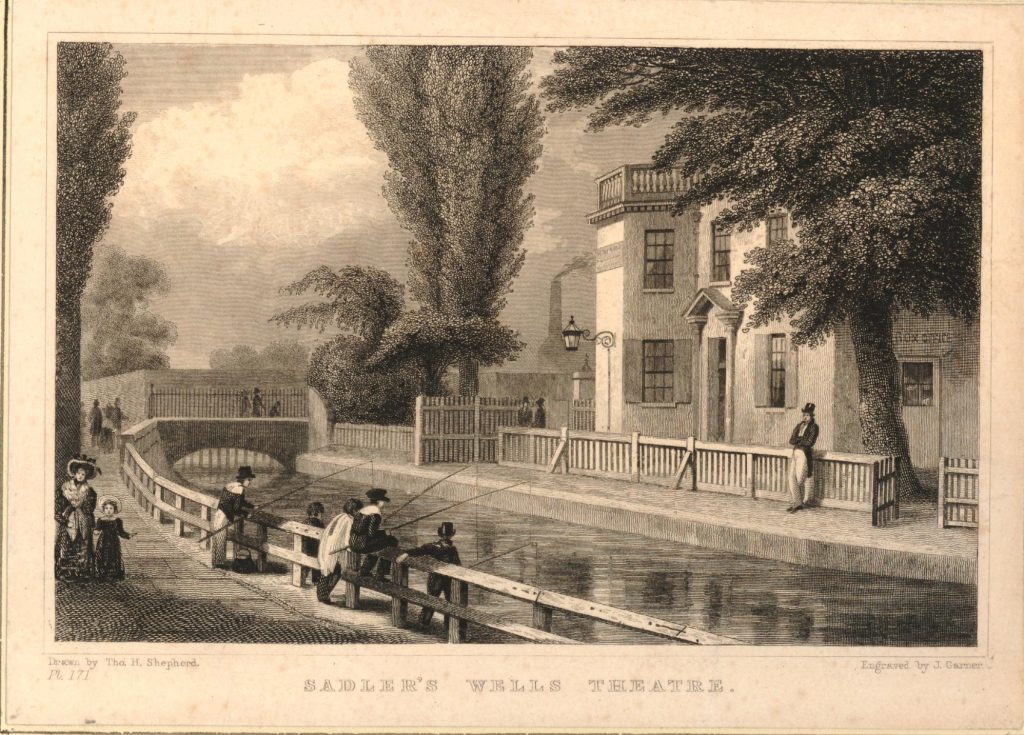

The view on the ticket presents Sadler’s Wells still in a rural setting. Trees in the gardens and the New River flowing alongside the boundary of the theatre.

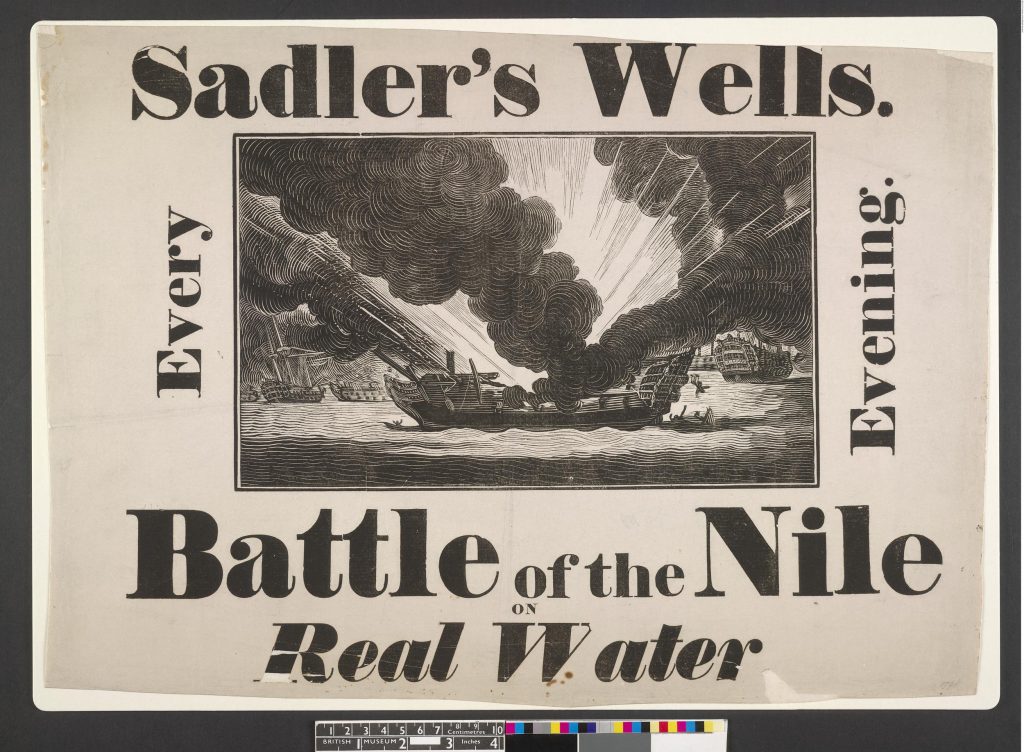

As well as the Siege of Gibraltar, another performance that made use of the water tanks under the stage was the Battle of the Nile, performed with “Real Water”.

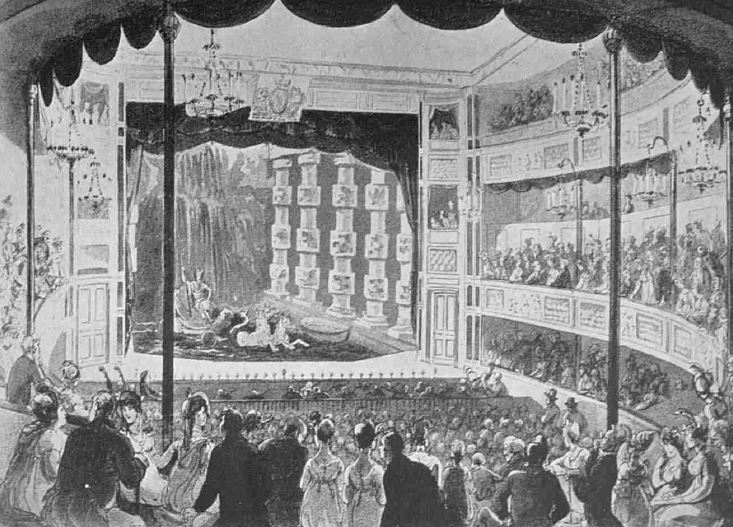

We can get an impression of the interior of the theate during one of the aquatic performances from the following print. The boards on the stage have been removed and the performance is now taking place in a large tank of water.

It was common for audience members to throw themselves into the water at the end of a performance – probably with the help of plenty of alcohol consumed during the evening.

Competition for London audiences was intense, and perhaps more difficult for Sadler’s Wells having a location outside the centre of London. The theatre was always on the look out for ever more dramatic and daring events.

in May 1833 Sadler’s Wells announced that there would be a stupendous representation of the Russian Mountains. This consisted of “sliding down at break-neck speeds in cars along a highly inclined plane of wood, previously laid over with blocks of ice united into a mass of water thrown purposely over them. The cars descended with great velocity from a considerable height at the extremity of the stage across the orchestra to the back of the pit”. No record of what must have been a number of injuries from this performance.

A colour print of the entrance to Sadler’s Wells with the New River running alongside:

The following print from 1830, also shows Sadler’s Wells and the New River, but look at the background, just to the left of the theatre and there is a smoking chimney – the pump house at New River Head.

From the 1840s onwards, the performances put on by Sadler’s Wells started to change. No more dancing dogs or representations of sea battles, rather more intellectual and improving performances. Samuel Phelps, the manager at this time planned to put on productions of all of Shakespeare’s plays. He succeeded with 30 plays, and under his management there were four thousand nights of Shakespeare’s plays with Hamlet being put on for 400 nights.

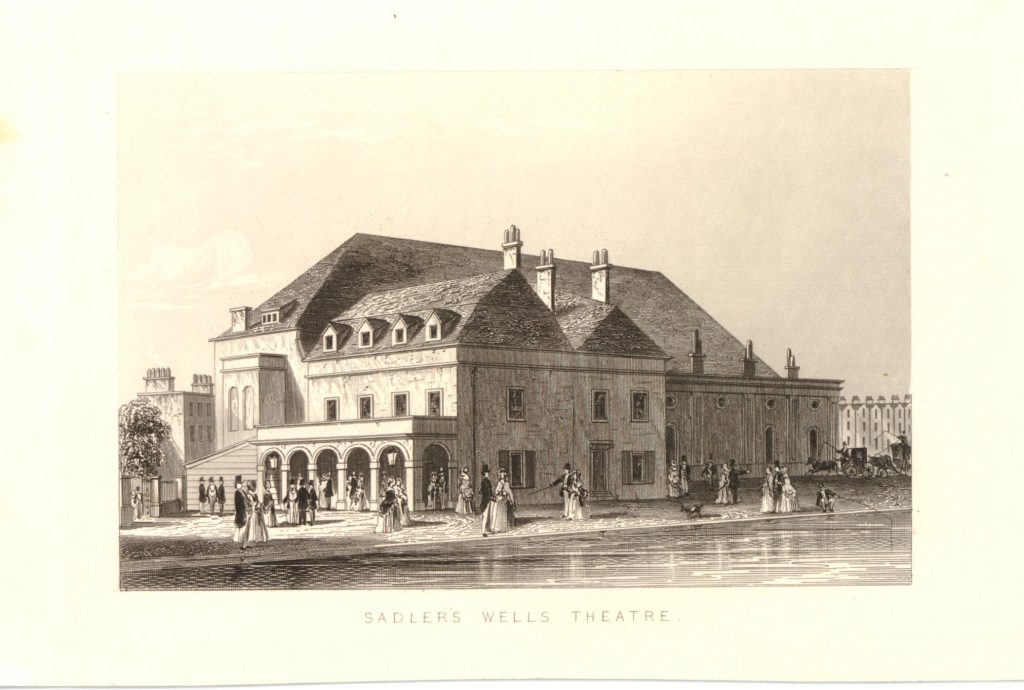

By this time, Sadler’s Wells was a substantial theatre. London had now grown out from the centre and surrounded the theatre, which had also lost most of the gardens and trees. The theatre in 1850:

Although by the second half of the 19th century, Sadler’s Wells was putting on serious productions, some were not without controversy, such as when the American actress Adah Menken appeared in May 1868. The Era provides the following description of the performance:

“SADLER’S WELLS – Miss Menken has been giving her celebrated impersonation of Mazeppa at this house during the week. The audiences have been good, and the far famed actress has nightly been received with great applause. Though Mademoiselle causes a sensation by appearing very sparsely clad in the course of her performance, she is splendidly dressed at the commencement of it. Her page’s costume, which she wears as Casimer in the first act, is of the most costly and gorgeous nature. Whatever may be thought of the propriety of a lady making a public exhibition of her figure, with the outlines of it almost as distinct as those of a piece of undrapped sculpture, there can be no question that the beauty of the form displayed by Miss Menken is of remarkable character”.

In the latter decades of the 19th century, Sadler’s Wells went through a period of considerable change, and a variety of uses. During one period of four years, the theatre had eleven managers. Shows were put on, but they were not successful enough to attract the funding needed.

In 1875, 104 pounds of lead were stolen from the theatre’s roof. There were rumours that the building might be sold for a furniture warehouse, but by June 1876, the theatre had been converted and reopened as the New Spa Skating Rink and Winter Garden – however this use failed within a couple of months.

The building was used for boxing and wrestling matches, although these events were closed down by Police. In 1878 an application for a theatre licence was refused because the building still had wooden stairs which were considered a danger compared to stone stairs.

The theatre did manage to stagger on, putting on a range of different productions from variety to serious drama – all with variable success. For a short time at the start of World War I, the building was in use as a cinema.

Real change came in 1925. The Old Vic, south of the Thames was run by Lilian Baylis, and during the 1920s the plan to expand north of the river was considered. Baylis pursued the idea of purchasing Sadler’s Wells and engaged as many people in public life as possible to support the proposal, and to raise funds. On the 30th March 1925, a public appeal was launched:

“To purchase Sadler’s Wells (freehold), reconstruct the interior, and save it, with its historic traditions, for the Nation,

To establish it as a Foundation, not working for profit, under the Charity Commissioners, and by providing for its use by the Old Vic Shakespeare and Opera Companies, conjointly with their present Theatre in the Waterloo Road, to give an old Vic to North London”

The appeal was successful, and a new theatre was designed by F.G.M. Chancellor, opening on January 6th 1931, with a performance of Twelfth Night (suitable for the date), with John Gielgud.

The new theatre brought together Opera and Ballet, and included a School of Ballet.

The new theatre still retained the well, which was to be found at the back of the pit, concealed under a heavy iron plate. Here, a Miss Noble tests the depth of the well:

The 1931 building is shown below, as it appeared in the early 1970s, looking from the same viewpoint as my 2020 photo at the top of the post:

After the war, the ballet company of Ninette de Valois which had formed at Sadler’s Wells moved to Covent Garden to become the Royal Ballet.

The theatre continued the long tradition of dance and the D’Oyly Carte Opera performed seasons at Sadler’s Wells. The theatre hosted touring companies from across the world. However there were financial challenges, rumours that the site may be sold as part of development plans from the New River Company (which by then was a property company).

In the 1990s there was again significant change at Sadler’s Wells, with a campaign for a new, purpose built dance theatre. The campaign was successful, including a significant £36 million from the National Lottery.

The new theatre opened in October 1998, and continues the tradition of dance and entertainment on this site in north Clerkenwell / islington well into the 21st century.

I started the post talking about how this area of London has been shaped by water. If the location had not been the site of a well, the name would be very different, and perhaps also without the initial fame of the well, Sadler’s original gardens and music house may not have continued too much further than the 17th century.

Although the area is very different to the fields covering the area in the 17th century, the water is still there, deep below the surface. A borehole in the sub-basement of the theatre descends some 600 feet to the chalk basin that runs under London, from where water is taken for the sinks, toilets, heating and cooling of the theatre. The borehole supplies water at a rate of 12 litres a second and at a temperature that varies between 11 and 12 degrees Centigrade.

Walk down Arlington Way, to the west of the building and there is a door facing onto the street, to the right of the large grey door.

On the door is a sign confirming the location as the site of the Sadler’s Wells Borehole pumping station, where Thames Water are also extracting water from far below the surface.

Thames Water hold the licence to extract water from the borehole, however up until 2004, the Sadler’s Wells Trust held a licence to extract water for water bottling. I cannot find any reference after 2004, so I suspect that was the last time you could buy bottled water drawn from below the theatre.

Again, a weekly post only allows me to scratch the surface of the history of Sadler’s Wells.

The History of Clerkenwell by William J. Pinks provides a detailed history of the first couple of centuries of the theatre. The Story of Sadler’s Wells by Dennis Arundell provides a detailed history up until 1977, and the Survey of London, volume 47 provides the usual highly detailed history. All prints used in this post are © The Trustees of the British Museum

Sadler’s Wells, a very successful theatre that owes its name and probable longevity to a patch of gravel and discovery of a well in the fields of Clerkenwell.