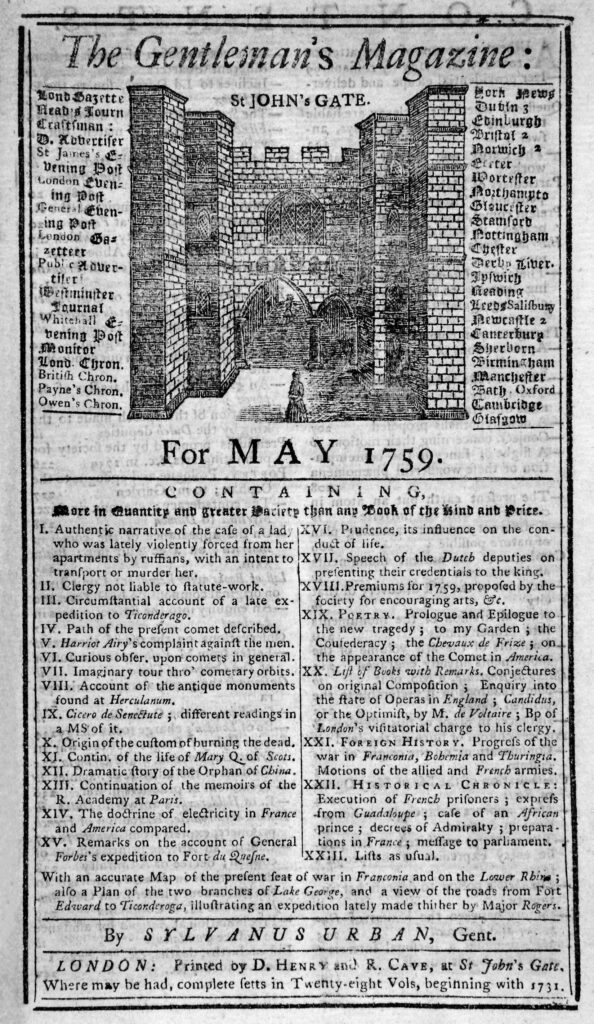

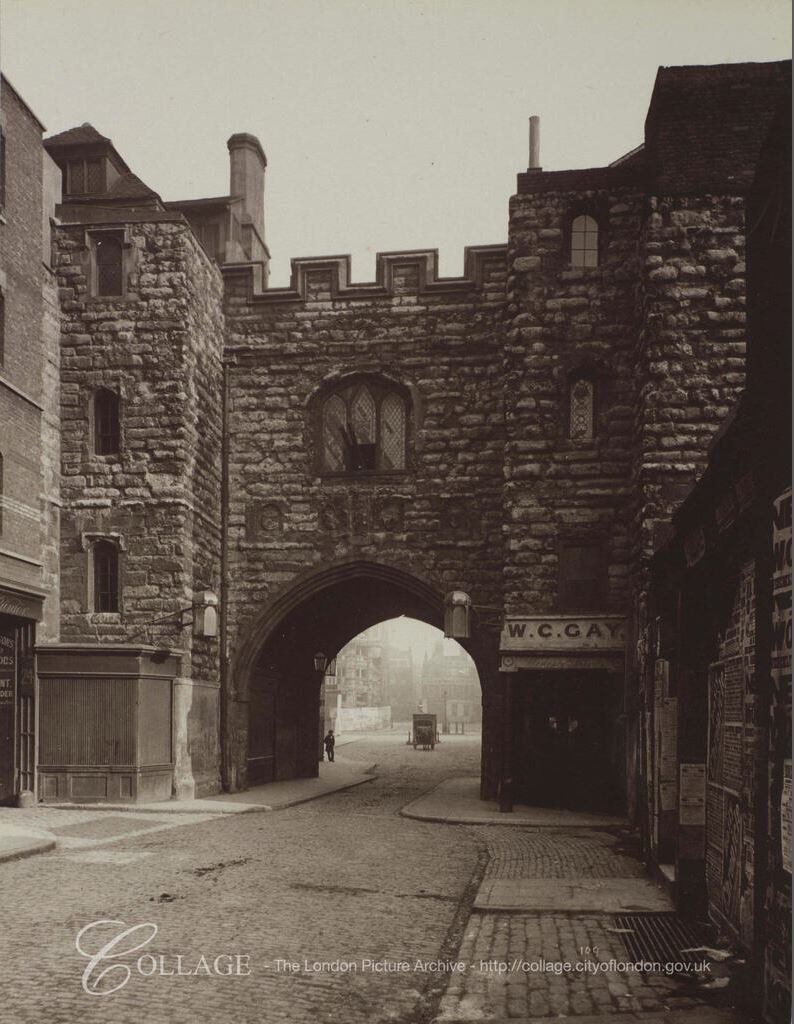

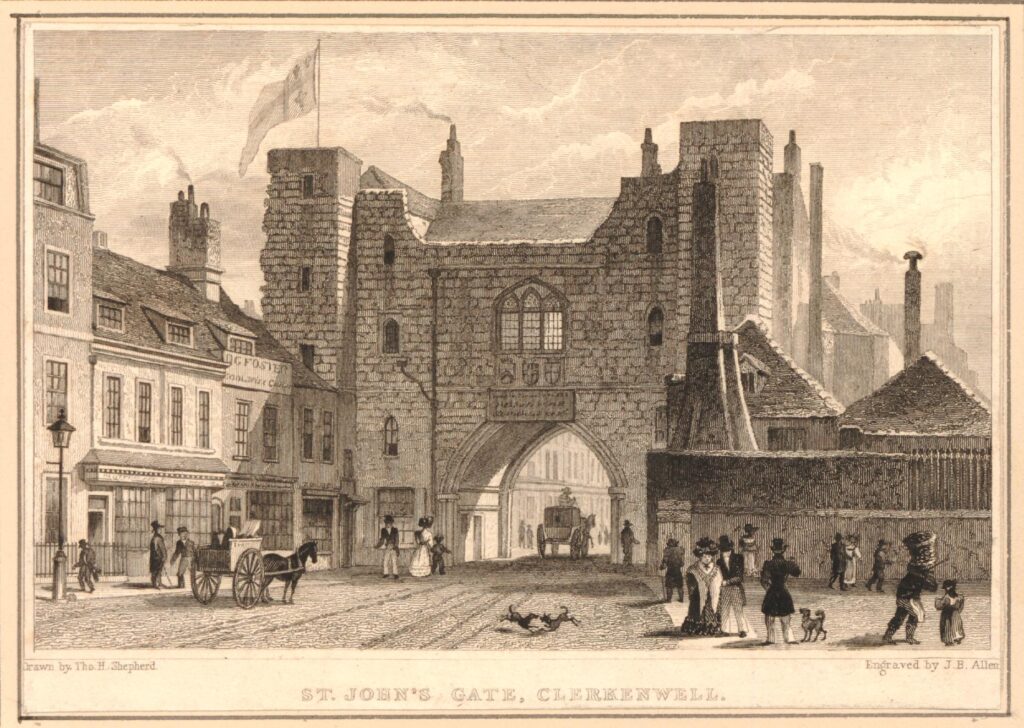

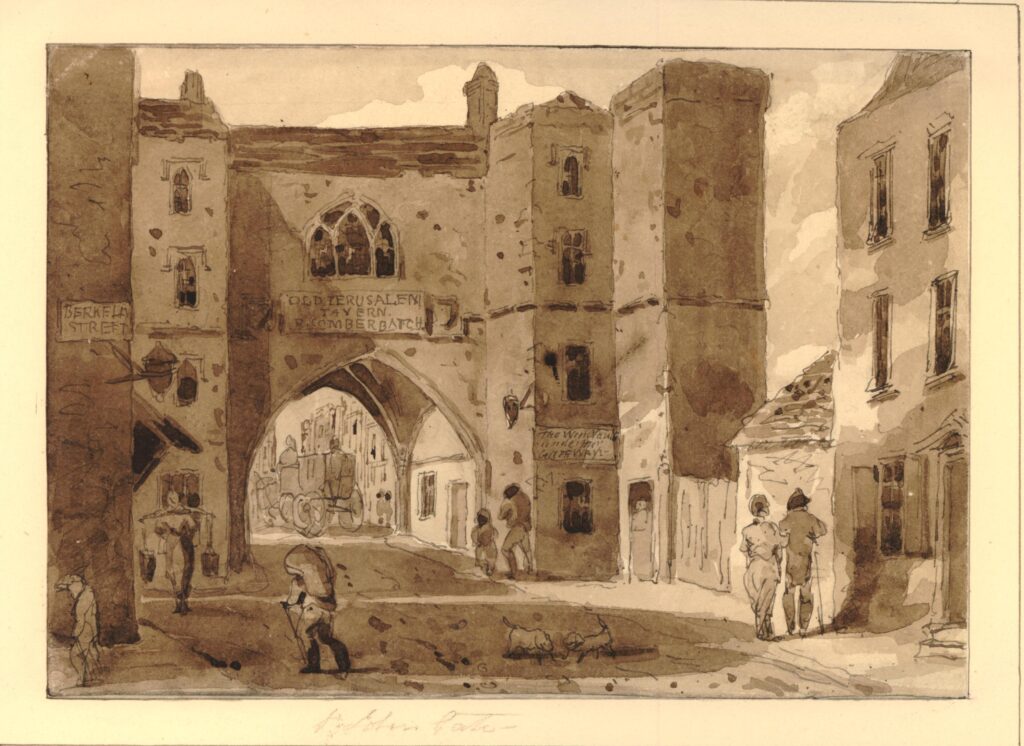

For this week’s post, I am back in Clerkenwell, an area I have explored in a number of recent posts, and today I will take a walk along St John’s Lane, a street that runs from St John’s Street, up to St John’s Gate.

Although St John’s Lane is relatively short, there is so much that the street can tell us about the history of the area, events across London, and the people who have passed through London.

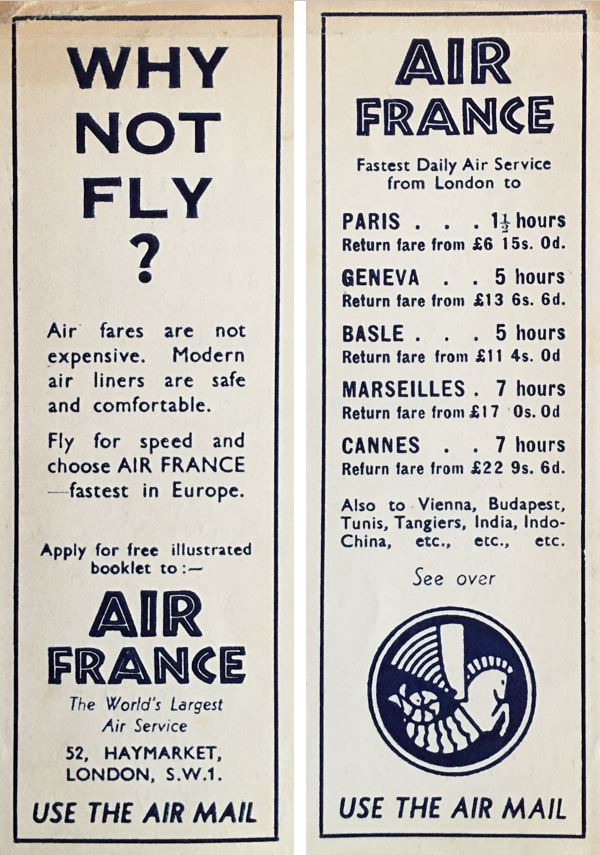

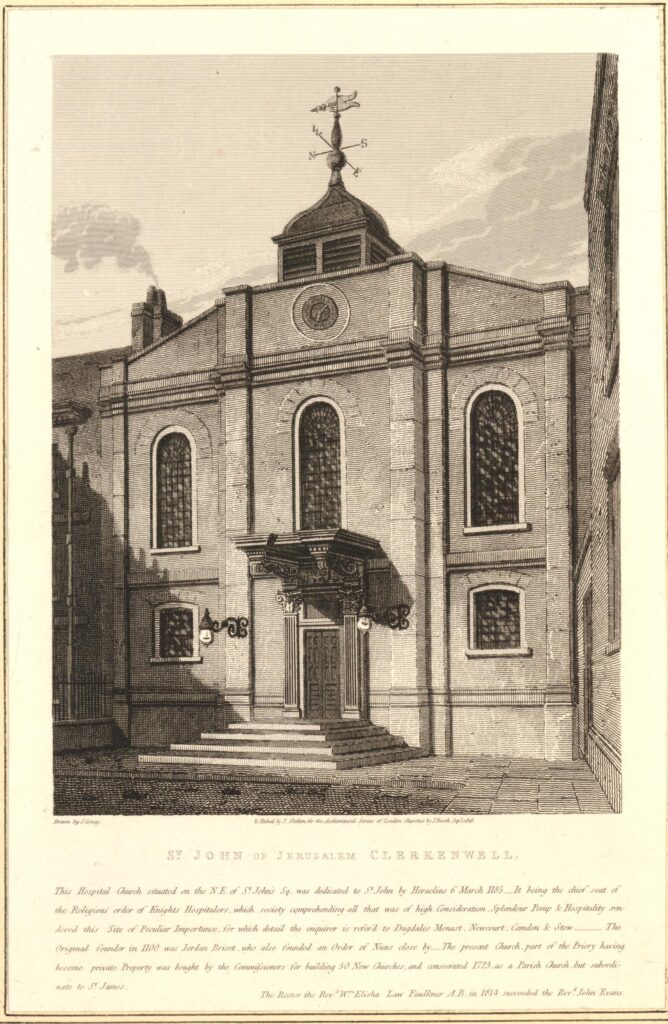

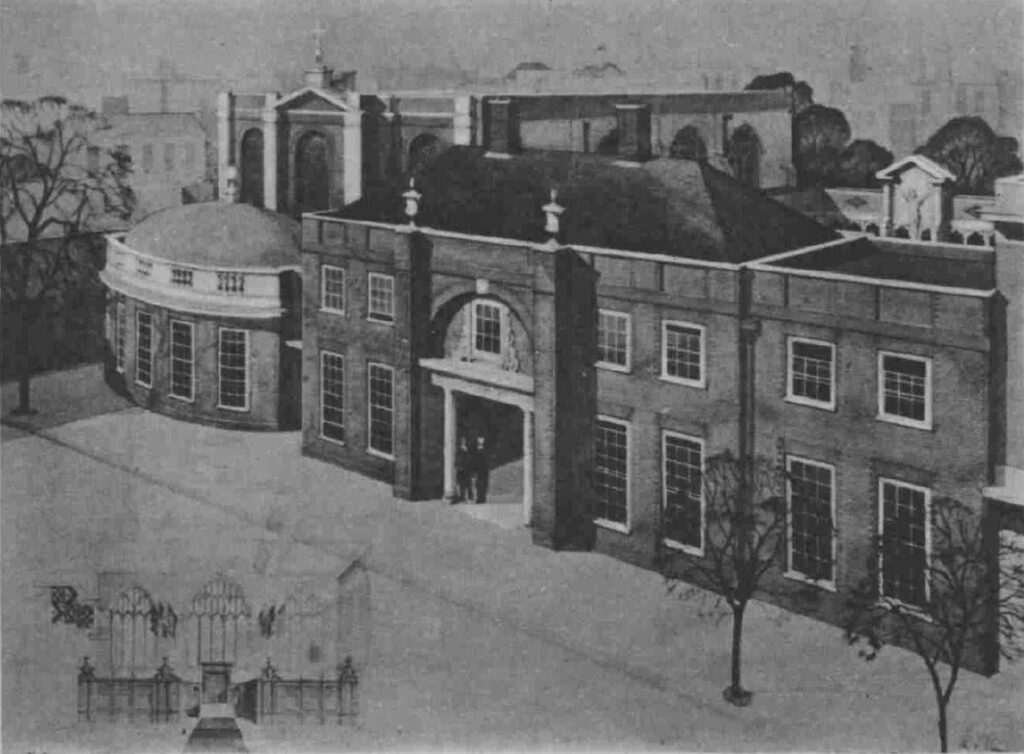

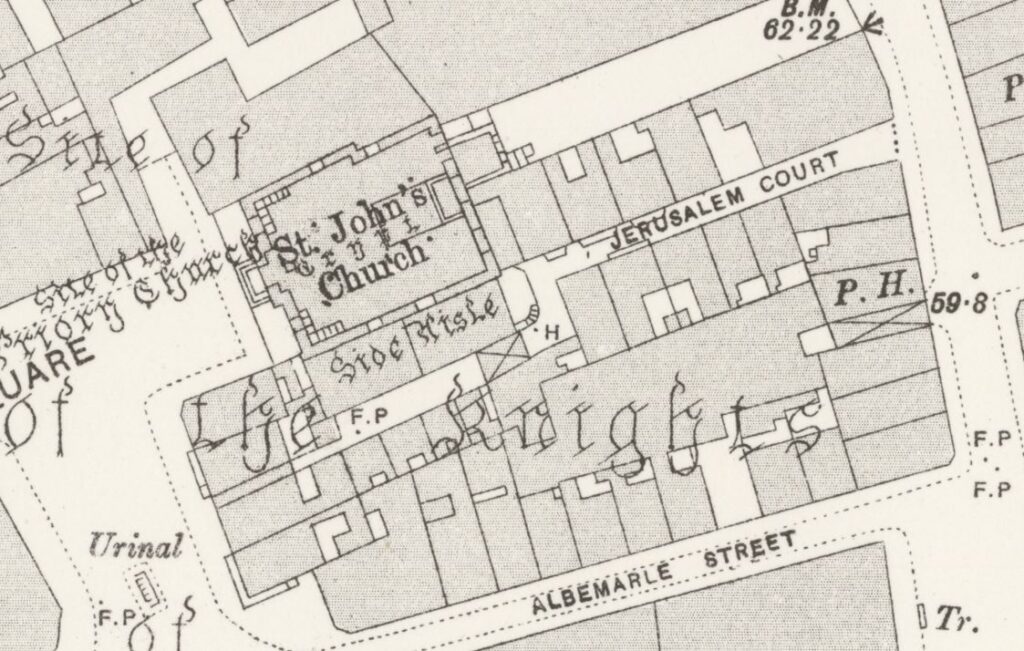

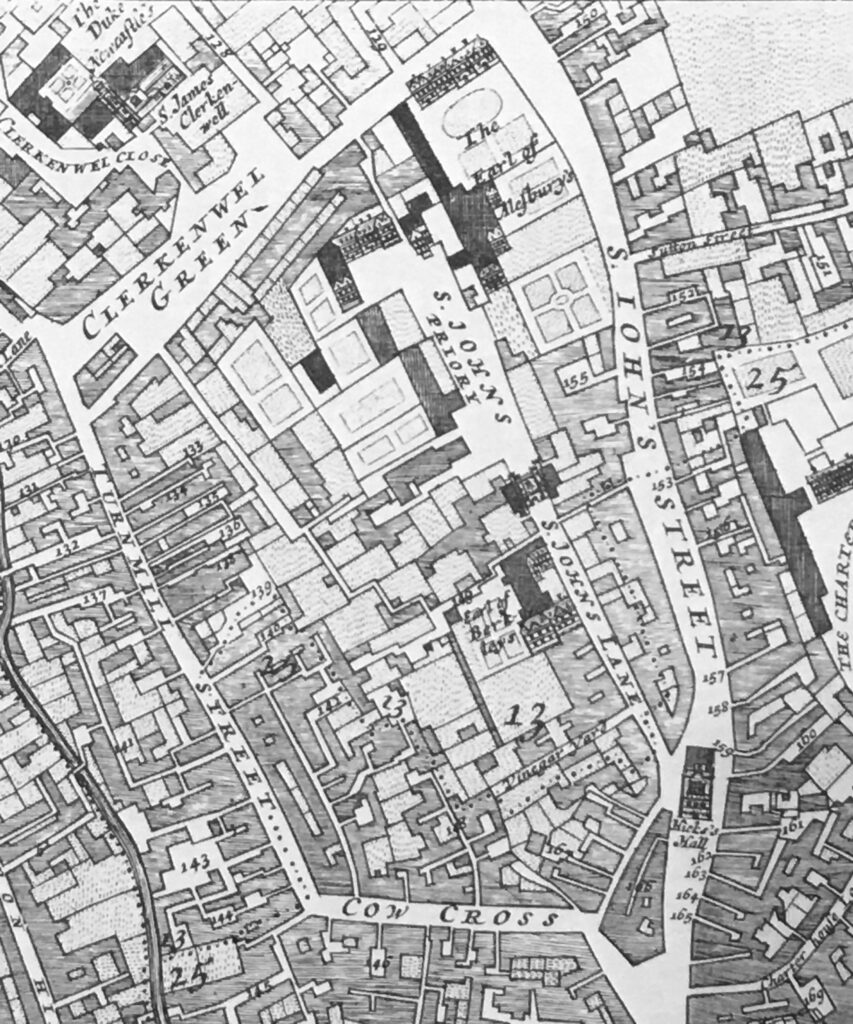

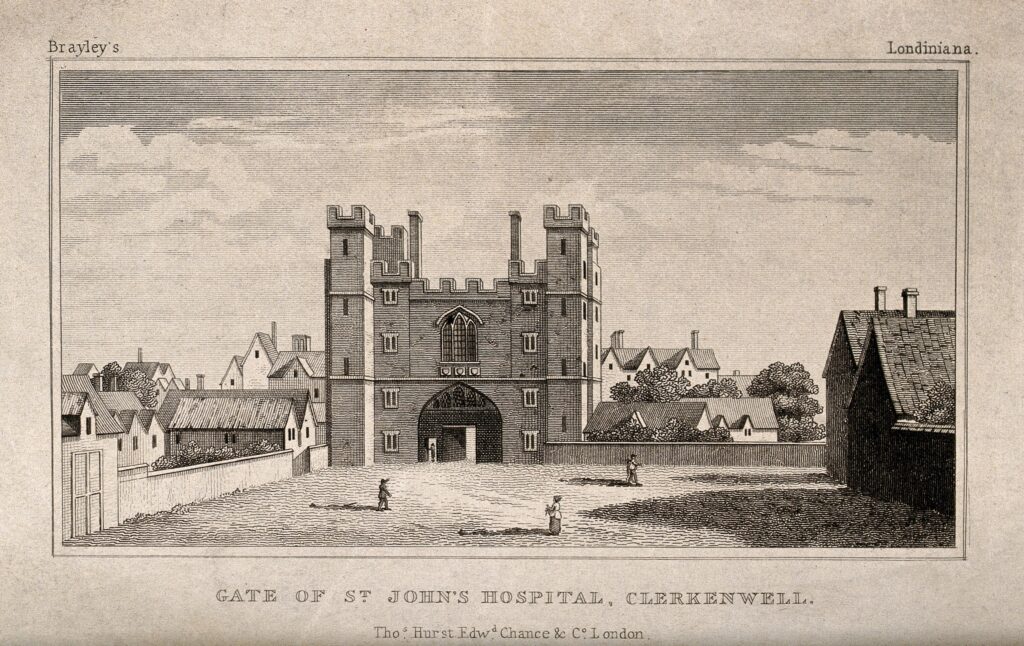

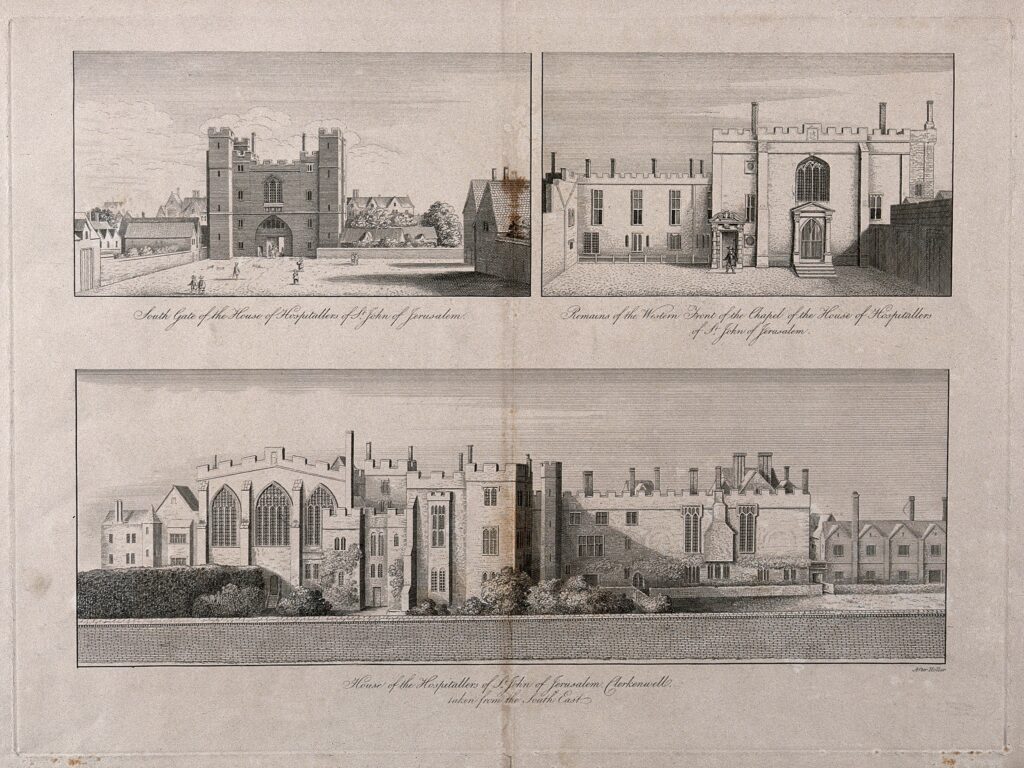

St John’s Lane is a very old street, dating back to the 12th century. The street originally ran through the outer precinct of the Priory of the Order of St John of Jerusalem, leading from a gate at the southern end, to St John’s Gate at the northern end, which formed the gateway to the inner precinct. The following map is repeated from my earlier post on the Order of St John, and shows St John’s Lane between the two blue rectangles, which represent the gatehouses into the outer and inner precincts (Map © OpenStreetMap contributors).

St John’s Lane today, photographed from the south, looking up towards St John’s Gate just beyond the trees at the end of the street.

St John’s Lane today is mainly lined by late 19th and early 20th century buildings, along with a number of post war buildings, mainly on the western side of the street which suffered a higher degree of bomb damage during the last war.

During the time that St John’s Lane was part of the outer precinct of the priory, the street was lined by buildings associated with the priory, including a number of large houses with gardens to the rear, owned by important members of the Order of St John.

The Clerkenwell News of the 16th December 1863 included a very imaginative and colourful description of St John’s Lane in an article on the history of the street “What a glorious picture does imagination, aided by the indubitable facts of history, present of the splendid pageants which, in the days of chivalry, passed along this highway, their pomp and splendor offtimes swelled by the gorgeous retinue of some kingly potentate or prince of royal blood. What an array have we of glittering lances, blazoned shields, and fluttering pennons – heralds in their gaudy tabards – knights, the flower of England’s nobility, mounted on stately charges, richly caparisoned. Obsequious esquires, and the fair dames and daughters of nobles, grace by their presence the magnificent cortege, pleased to follow their lords and loves to the tournament in the neighbouring Smithfield”.

After the priory was taken by Henry VIII during the dissolution in the 1540s, many of the buildings and much of the land was sold off, however evidence of the large houses that once lined the street could still be seen in the 17th century.

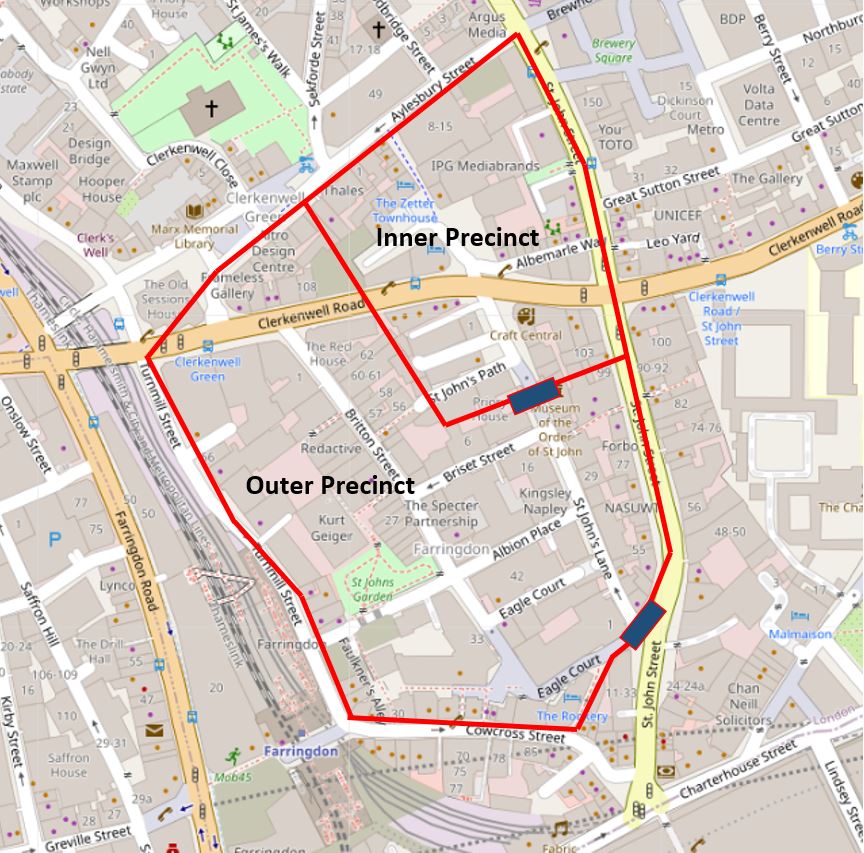

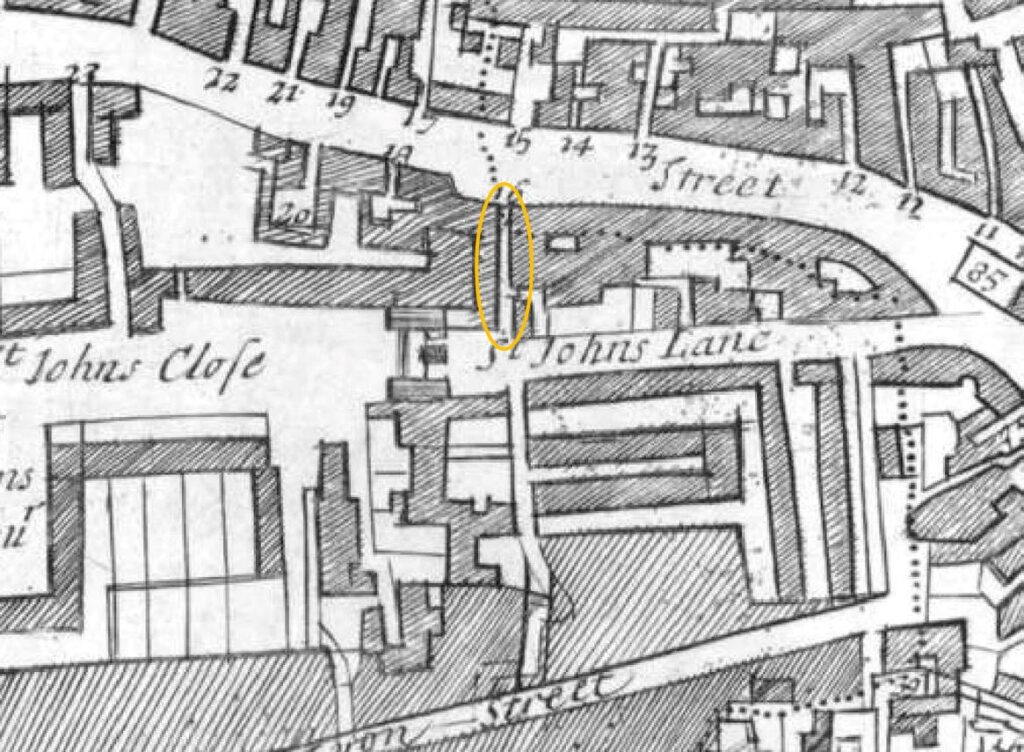

The following extract from William Morgan’s Survey of London from 1682 shows St John’s Lane in the centre of the map, and to the left of the upper part of the street is the house and grounds of the “Earl of Berkleys”.

By the end of the 19th century, the street was a mix of different type and use of buildings. There were terrace houses, a pub, a Friends Meeting House, a Smithy, along with a mix of industrial buildings and workshops supporting the trades that had moved into Clerkenwell.

Only a few of these buildings can be seen today. The Friends Meeting House was destroyed during the war, and in 1992 the following building was completed on the site.

This is Watchmaker Court, an office building with a name that recalls one of the crafts / industries that was based in Clerkenwell from the late 17th to the early 20th centuries.

A clock stands out from the front of the building, telling the time in Roman numerals.

There are eight plaques along the front of the building, each naming a significant clock maker in chronological order, starting with Dan Parkes:

One of those named is Christopher Pinchbeck, who lived in Albion Place, one of the streets that runs off St John’s Lane to the west. Pinchbeck invented an alloy of copper and zinc which very nearly resembled gold.

On the northern side of Watchmaker Court is the building that was once the pub, the Old Baptist’s Head:

The building that we see today is a rebuild of the pub dating from the 1890s, however the pub had been on the site for many years, originally being part of the house of Sir Thomas Forster, who died here in 1612.

There seem to be various post war dates for when the pub closed, however by 1961 the building had been converted to a warehouse.

There is nothing really remarkable about the old pub building, in what is now a relatively quiet street. The pub has played a part in the life of so many who have passed through London over the centuries.

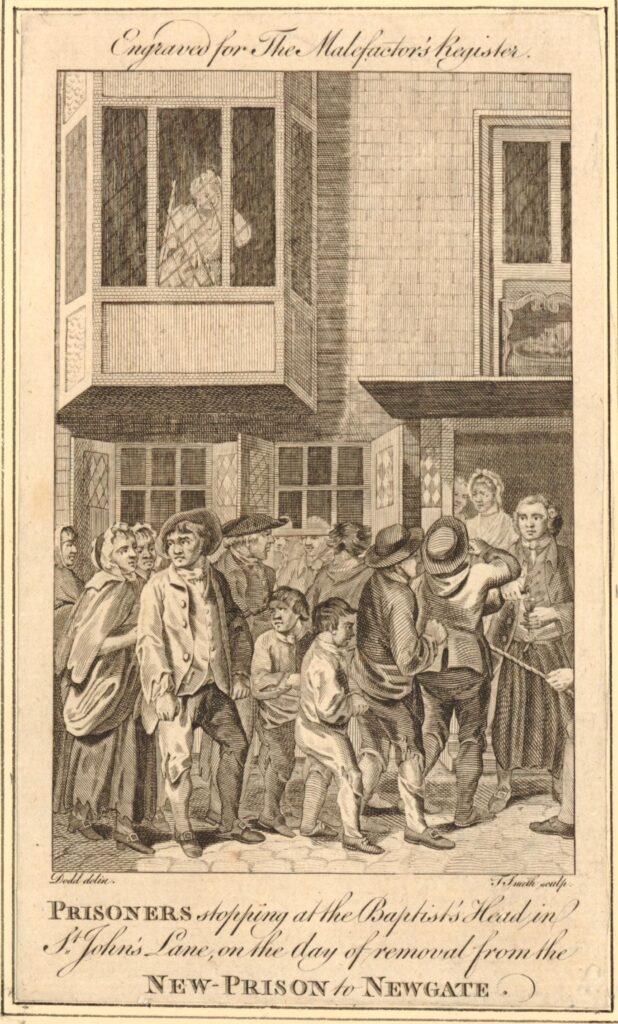

From the same article of the Clerkenwell News that I quoted above, is a comment that the Old Baptist’s Head was a halt for prisoners on their way to Newgate. The British Museum archive includes a 1780 print of prisoners stopping at the pub (the two following prints are ©Trustees of the British Museum, Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) license):

The New Prison was the Clerkenwell Prison, or the Middlesex House of Detention that I wrote about in a previous post on Sans Walk, a Fenian Outrage and the Edge of London. The Old Baptist’s Head, or just the Baptist’s Head as it was in 1780 was about half way between the prison and Newgate, so I assume the prisoners were allowed a stop for refreshments.

A very different stop at the Old Baptist’s Head was recorded in the District News on Friday the 29th June, 1900. There is an article by a St John Ambulance volunteer who was on his way from Hebden Bridge in West Yorkshire to the Transvaal in South Africa.

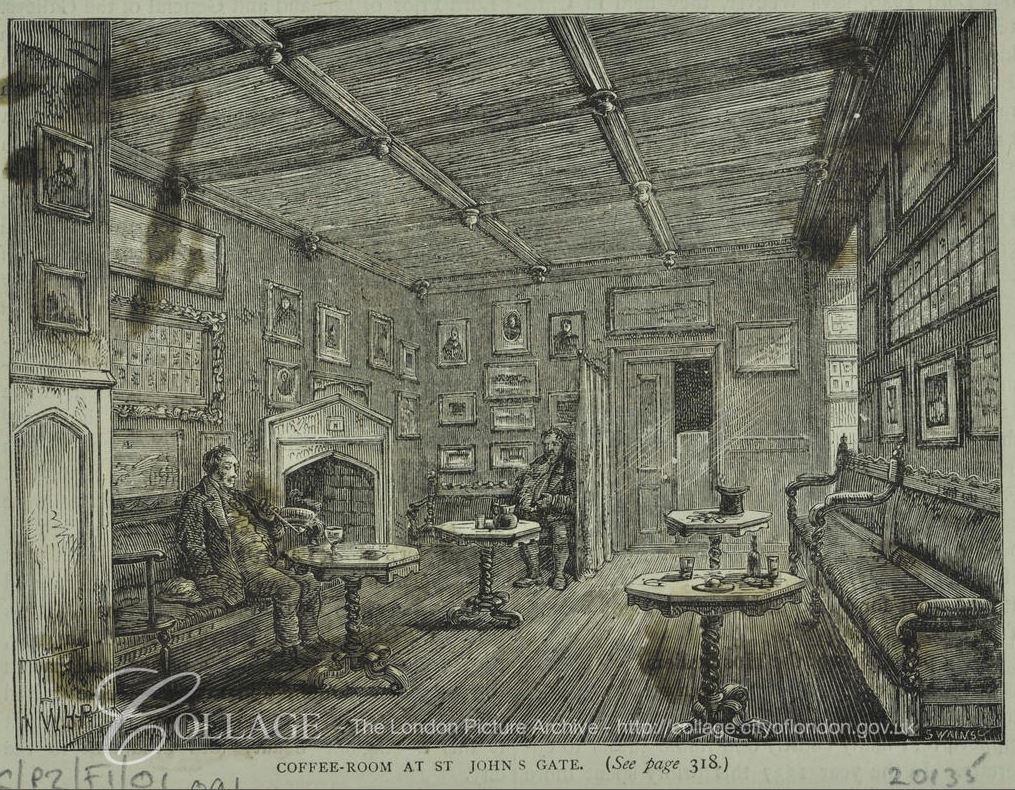

He arrived in London at King’s Cross and then made his way to the Old Baptist’s Head where accommodation had been arranged by the St John Ambulance (who had their headquarters at the nearby St John’s Gate). The article tells of an early morning, 5 a.m. exploration of London, before heading to Aldershot via Waterloo for training, then to Tilbury to catch a boat to South Africa.

Whilst buildings such as the old pub now serve a different purpose, it is fascinating how many have passed by the Old Baptist’s Head; from prisoners to volunteers heading from Yorkshire to South Africa. There must be millions of such individual stories across London.

A relic of the time when the Old Baptist’s Head was a pub can today be seen in St John’s Gate. A fire place originally belonging to the pub is now in the Old Chancery room of St John’s Gate. The fireplace includes the coat of arms of Sir Thomas Forster, so is presumably from his house prior to part being converted to the pub.

The following print shows the fireplace in the Old Baptist’s Head:

The following photo is of number 29 St John’s Lane. An early 1880s warehouse built for the wholesale stationers Fenner Appleton & Co.

Although now converted to offices and flats, the building retains the large doors on floors one to three that would have been used to move goods between the street and the warehouse floors.

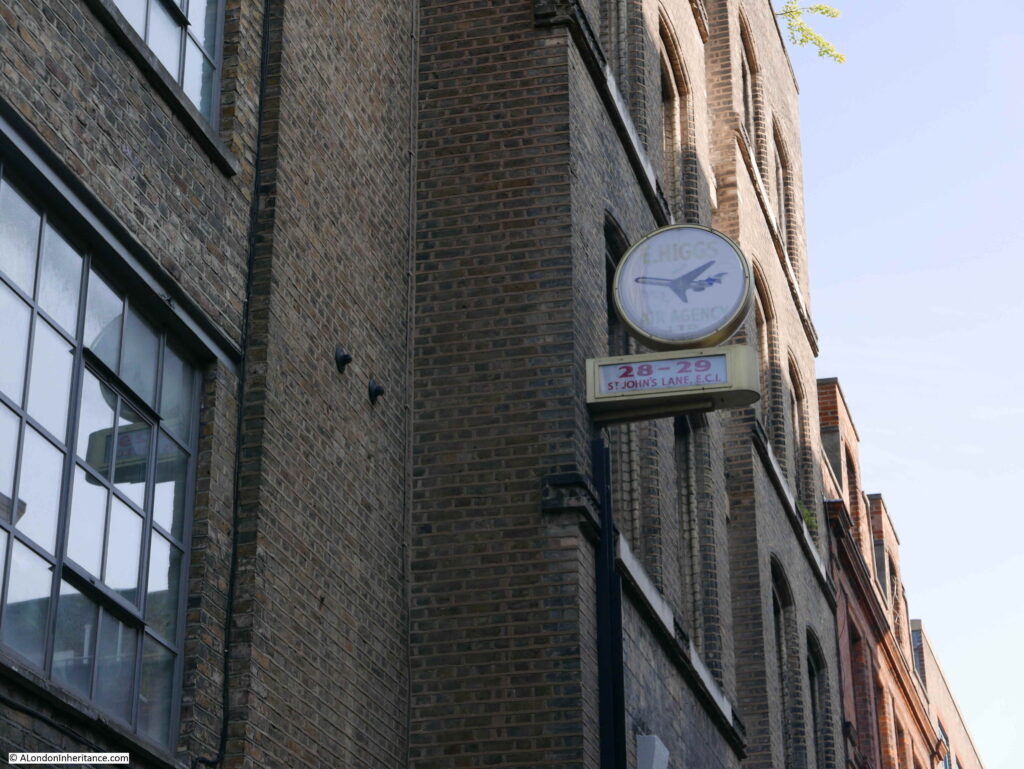

On the front of the building is a superb clock:

On one face of the clock is an outline of the world, and on the other side is the name E. Higgs Air Agency Ltd.

I am always rather cautious with relics such as this clock as to whether they are actually genuine.

There does not seem to be much information available on the company. They were on the delegate list to a World Air Transport Conference held at the Royal Lancaster Hotel on the 8th and 9th of May 1974, but despite leaving a rather good clock, they do not seem to have left much else in Clerkenwell.

There is today a company called Higgs International Logistics that provides logistics for the publishing industry, and given Clerkenwell’s history with the printing industry, perhaps the company now in Purfleet, Essex is the latest incarnation of the business in St John’s Lane.

If it is, I am pleased that they left their clock.

At number 28 is a large warehouse and offices dating from 1901:

This building is part of a tragic period of London’s history, as hinted at by the plaque on the front of the building.

Although minimal compared with the Second World War, London was bombed during the First World War.

Early attacks during the war were by Zeppelin airships (see my post on Queen Square), and during the later years of the war, the Germans switched to the use of aircraft to bomb London.

The first fleet of German aircraft attacked London on Wednesday, the 13th of June 1917. Sporadic raids continued during the following months, and night raids commenced in September.

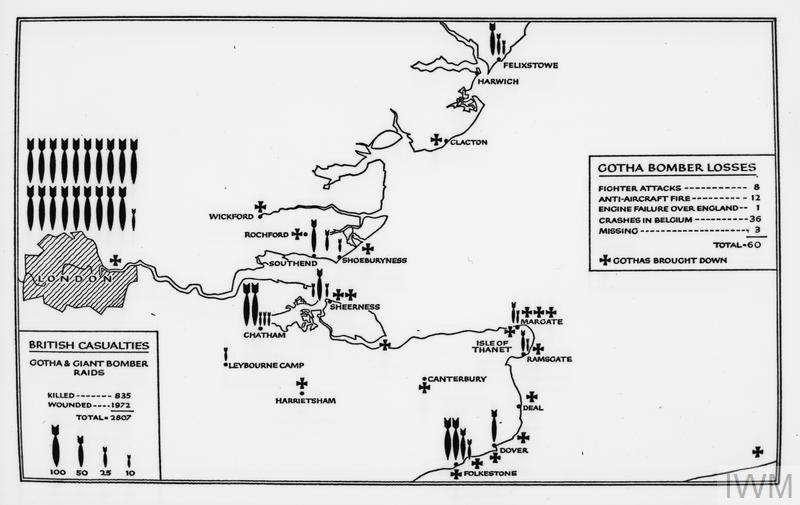

On the night of the 18th December 1917, a fleet of sixteen aircraft set of from Belgium, and thirteen “Gotha” bombers and a single “R-plane or Giant” bomber reached London, where they dropped their bombs across the wider city causing considerable damage, including in St John’s Lane.

On the route from Belgium and return via London, the planes dropped 2475kg of high explosive on London, 800kg on Ramsgate, 450kg on Margate and 400kg on Harwich. One of the Gotha bombers was shot down by a Sopwith Camel flying from an airfield at Hainault in Essex. The bomber crashed in the sea off Folkestone.

It is remarkable that aircraft of 1917 had the range and lifting capabilities to carry heavy loads of high explosive bombs from Belgium to London and across Essex and Kent.

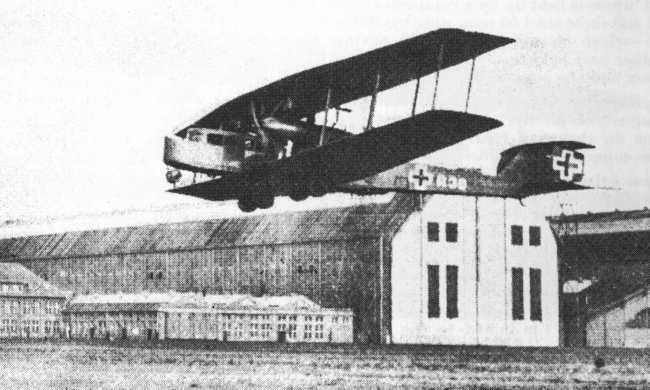

The Gotha was a twin engined heavy bomber that entered service in August 1917. It had a range of about 520 miles and a maximum speed of 87 mph. The Gotha was capable of carrying up to 14, 25kg high explosive bombs. For the crew, it was unpressurised and there was no heating, so it must have been incredibly uncomfortable for the crew on long night flights from Belgium to London and back.

The Gotha Heavy Bomber of the type that attacked London on the night of the 18th December 1917:

A single R plane was also involved in the raid on the night of the 18th December 1917. The R plane, also known as the Giant, was a four engined heavy bomber, with a maximum bomb load of 4,400 lbs of high explosive bombs and a range of 500 miles.

The R plane had two engines on each wing, one in front of the other. The front engine had a forward facing propeller that pulled the aircraft, the rear engine had a rear facing propeller and pushed the aircraft. Remarkably, the engines were capable of being serviced in flight and a mechanic was stationed in each of the engine pods during the flight.

The R Plane, or Giant bomber of the type that attacked London:

(image source https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Zeppelin-Staaken_R.VI_photo1.jpg):

A map in the Imperial War Museum archive provides an overview of the Gotha bomber attacks on London, Kent and Essex during the later years of the First World War and illustrates the considerable numbers of bombs dropped on London, casualty numbers and the number of Gotha bombers lost.

The attacks on London during the First World War, though relatively small in number, were an indication of what was to come in just over 20 years time.

The building next to number 28 has an interesting ground floor frontage to the street, part of which provides access to an alley.

Behind this building, in space between St John’s Lane and St John’s Street was a large area for the stabling of horses. The large arch on the left of the building was originally an access tunnel to the stabling area.

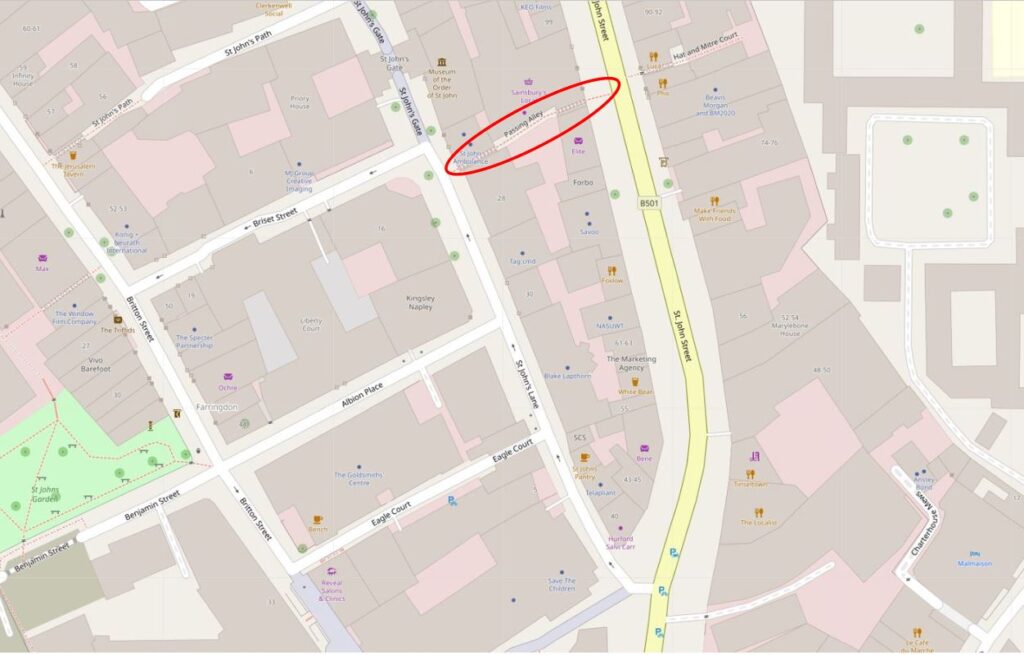

The smaller arch to the right provides access to Passing Alley, an alley that allows pedestrian access through to St John’s Street.

Passing Alley gives the impression of being one of London’s ancient alleys, however in London terms, it is relatively recent. The alley was originally around 40 feet to the north of its current location, however late 19th century development, which included the building that now provides access to the alley, required the shift of the alley to the south.

In the following map, I have outlined Passing Alley with a red oval. Look to the left of the alley, across St John’s Lane, and Passing Alley is to the south of Briset Street.

In the following extract from a 1755 parish map, I have circled Passing Alley with an orange oval. In this extract, the alley is in its original medieval position and was a continuation of Briset Street. The map also seems to imply that it was a slightly wider street than the narrow alley we see today.

The name of the alley seems to have changed in the late 18th century. In the key for the above parish map the alley was called Pising Alley, and in Rocque’s 1746 map it had the name Pissing Alley.

I cannot find any firm evidence for the source of this earlier name, however it may be down to the location of cesspits in the area.

Alan Stapleton’s 1924 book “London’s Alley, Byways and Courts” records that the alley was blocked for many months during the Great War due to the bomb dropped on the adjacent building on the night of the 18th December 1917, and that some hundredweights of bricks fell into the alley, killing an unfortunate man who happened to be passing through.

Walking through the alley today, and it is still lined by high brick buildings and walls, and one can imagine the impact of so many bricks falling into such a narrow alley.

The way the alley curves means that as you enter from either entrance, you do not get a view of the full length of the alley and what is around the corner.

As a complete diversion, I have mentioned a number of times the pleasure of finding things that previous owners have left in second hand books. My copy of Alan Stapleton’s book on London’s alleys contains a bookmark that was issued by Air France, detailing their flights from London. There is no date on the bookmark, but at the time, a flight from London to Paris would have cost £6, 15 shillings.

The following photo shows the St John’s Street end of the alley:

And the entrance to Passing Alley in St John’s Street:

If you are reading this post on the day of publication (Sunday 21st March 2021), then it is census day, the day every ten years when every household is expected to complete a census return providing details of those living at each address on the day.

A census has been carried out every ten years since 1801. The amount of information collected changes each census and 1841 was the first census when the names of all the individuals at an address were collected.

The census has been conducted every ten years apart from 1941, when the impact of the war meant that there other priorities. The 1931 census data for England and Wales was destroyed by fire – an early example of why backing up data is so important, although using the technology of the time with thousands of paper returns, this would have been difficult.

There was a register taken in 1939, not a full census, the data was needed to create ID cards and ration cards as part of the measures brought in during the war.

Availability of census data is goverened by the Census Act 1920, and the later 1991 Census (Confidentiality) Act. These acts restrict the disclosure of personal information from census returns until 100 years have elapsed, meaning that the 1911 census is the latest to be fully available. The 1921 census will be published online in 2022.

Given that the day of post publication is census day, I thought I would take a look at who was living in St John’s Lane in 1911, when the census was taken on the 2nd of April.

By 1911, St John’s Lane was home to a number of warehouses and business premises (as can be seen by gaps in the street numbering), however there were still 125 people living in the street, as detailed in the following extract from the 1911 census covering all the entries for St John’s Lane:

If you have seen the Government’s current advertising for the 2021 census, the emphasis is on the importance of the census to planning services such as transport, education and healthcare, however they also have an incredible historical importance as they provide a snap shot of the population at a point in time.

The 1911 census tells us the names of those living in St John’s Lane, their age, profession and their place of birth. We can therefore see the type of occupancy for the houses in the street (for example, in number 34, all the residents are single and recorded as Boarders).

We can get an idea of mobility by looking at their birth place. Many of those living in St John’s Street seem to have stayed relatively local. Out of the 125 residents, 82 are recorded as being born in London, of which 34 were born in Clerkenwell.

Only one family came from outside the United Kingdom. The Valli family at number 33 came from Italy, and we can get an idea of when they moved as their 18 year old daughter was born in Italy, but their 15 year old son had been born in London. The children also had some modern sounding jobs. The son was an apprentice to a Civil Engineer, and the daughter’s job shows the jobs that new technologies were bring to London as she had “Employment in the Telephone”.

The census also shows the tradition of people from Wales being associated with London’s dairy industry. At number three lived John Thomas Howells with his wife Margaret, both from Wales, with John being listed as a Dairy Man. They also had living with them two others from Wales listed as Servants.

A surprisingly high number were single, with 78 out of 125 being recorded as single, either as an adult, or because they were a son of daughter, widow or widower.

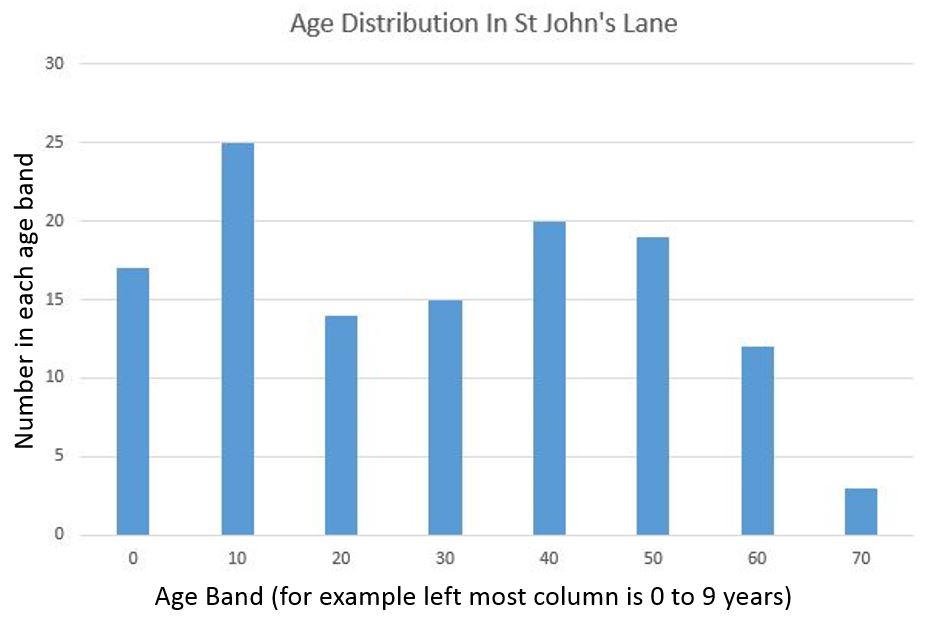

Displaying census data graphically helps with understanding what St John’s Lane was like in 1911. The following graph shows the age distribution, and highlights that the largest age group in the street was aged between 10 and 19.

The graph also shows the rapid decline in ages after the age of 59, with only three residents in their seventies. Of these three, two were married, Emma and John Cottrell at number four. Emma was 75 and had come from the small village of Frettenham in Norfolk. John was born in the City of London and at age 72 was still recorded as working as a locksmith.

So, as you complete the 2021 census, you may well be helping those who want to understand the history, demographics, mobility and professions of your street when the data is made public in 2122. Will your current job sound as strange to those in 2122 as an Ostrich Feather Curler sounds today?