Walk the side streets of Clerkenwell between Smithfield and Clerkenwell Road, and you will come across a rather ornate gate, standing over a narrow walkway between St John’s Lane and St John’s Square. This is St John’s Gate:

The reason for the Gate’s existence in Clerkenwell goes back to the founding of a hospital in Jerusalem around the year 1080.

Jerusalem has long been a pilgrimage destination, and in the 11th century a number of Benedictine monks founded the Order of St John and established a hospital to care for the sick of all faiths, and for pilgrims after the long and arduous journey. The work of the Order within a hospital led to them being called Hospitallers. Threats from Muslim forces to retake Jerusalem resulted in the Hospitallers taking on a military role, along with the continuing provision of a hospital and care for the sick.

The Hospitallers expanded across Europe, and their presence in England starts in the early decades of the 12th century with some small grants of land, leading to the foundation of the Priory of the Order of St John of Jerusalem in 1144 when 10 acres of land was granted to Jordan de Bricet in Clerkenwell.

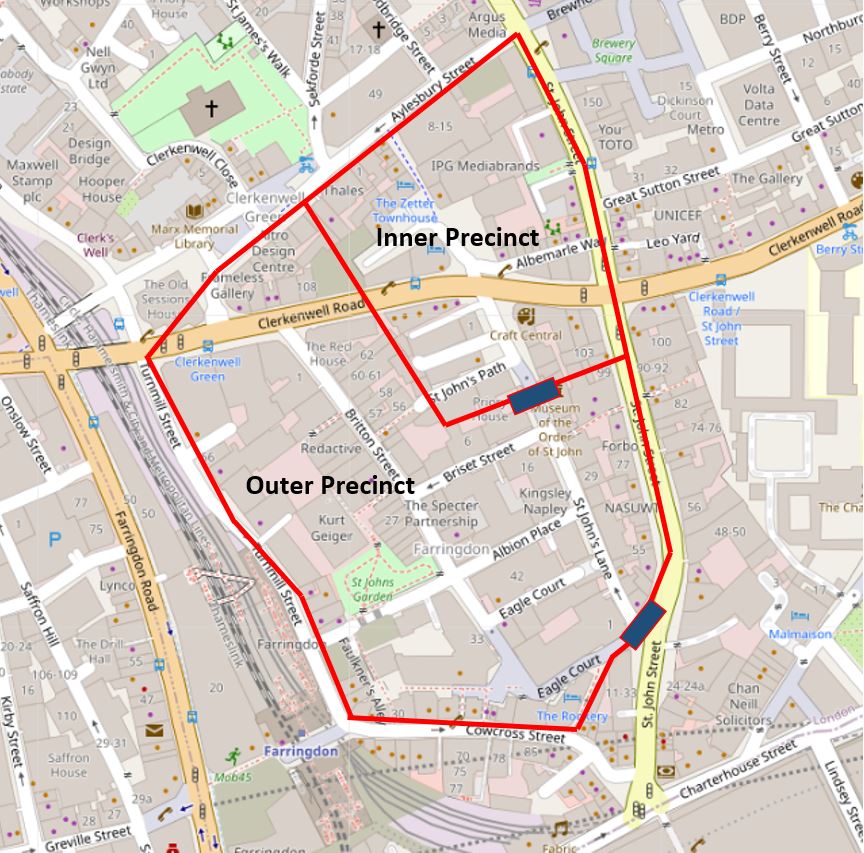

From the construction of a church between 1144 and 1160, the Priory grew to become powerful and wealthy. The ten acres of land was divided into an Inner and Outer Precinct with important buildings such as the Priory Church, the Prior’s Hall and the Great Hall within the Inner Precinct. The Outer Precinct included the houses of the knights of the Order, tenements for servants and workers, gardens along with the buildings needed to maintain an almost self sufficient operation.

The priory flourished until the 16th century, when Henry VIII’s efforts to divorce Catherine of Aragon and marry Anne Boleyn led to the king declaring himself as the Supreme Head of the Church of England, followed by the Dissolution of the Monasteries, when the Crown took control of the buildings, lands and income of religious establishments across the country.

The Clerkenwell priory was taken by the Crown, some officials of the priory were allowed to retain their houses, others were sold or granted to favourites of the king, and the buildings and land of the priory began the process of being broken-up, sold, demolished and rebuilt, that has resulted in this area of Clerkenwell that we see today.

The outline of the priory site can still be seen in the pattern of streets bordering the area.

St John’s Street formed the eastern boundary, Turnmill Street the western boundary, with Cowcross Street in the south and Aylesbury Street / Clerkenwell Green forming the north boundary. I have marked these on the map extract below, including the division of the inner and outer precincts (Map © OpenStreetMap contributors):

St John’s Lane formed the main approach to the inner precinct from the south, and the blue rectangle in the wall of the inner precinct is St John’s Gate.

There may have been some form of a gate at the southern entrance to St John’s Lane (shown by the lower blue rectangle). Research and excavations by the Museum of London Archaeology Service found mentions of tenements and possible evidence of a timber gatehouse (MoLAS Monograph 20 – Excavations at the priory of the Order of the Hospital of St John of Jerusalem).

The River Fleet, roughly along the alignment of Farringdon Road was at the western boundary of the site, and St John’s Street which ran up to Islington and was one of the main northern routes out of the City of London formed the eastern boundary.

At the time of the founding of the priory, the area was still mainly countryside, marshy land, springs and streams. The priory almost certainly had its own water supply, with a small tributary of the River Fleet, the Little Torrent rising at the south west corner of the Inner Precinct and flowing through the Outer Precinct to the Fleet.

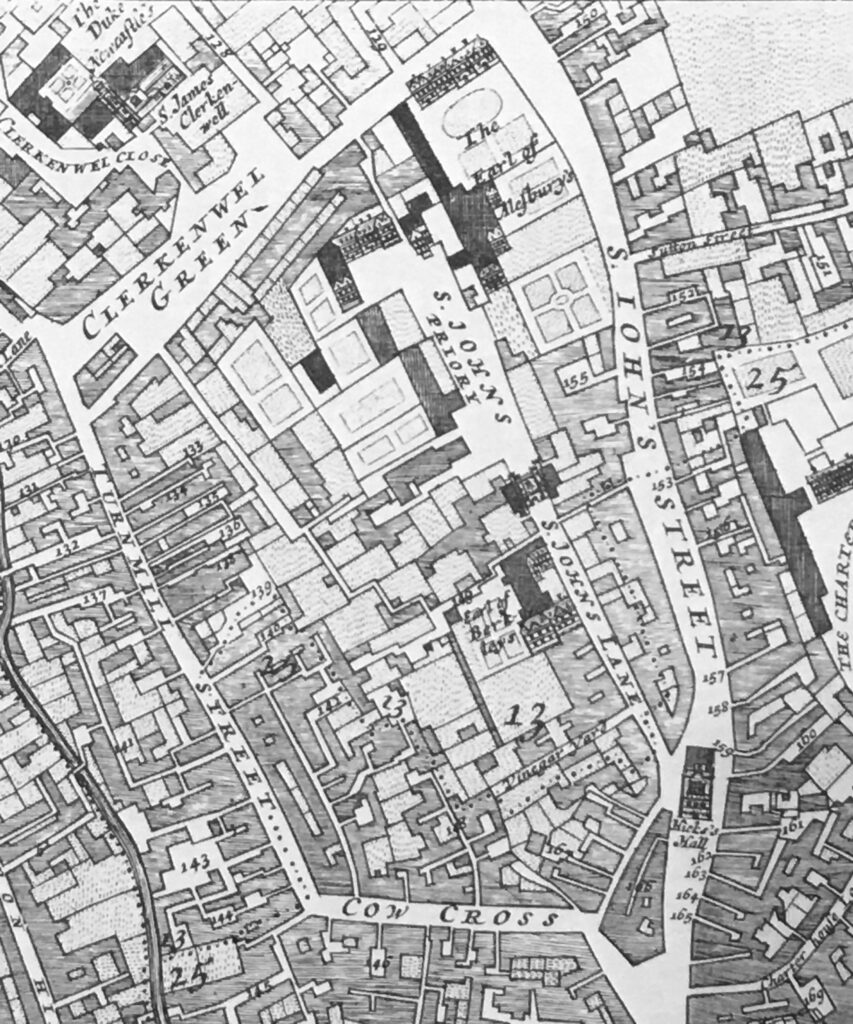

The original boundaries of the Priory stand out more in William Morgan’s 1682 Map of London which show the area before Clerkenwell Road cut through:

St John’s Gate can be seen at the end of St John’s Lane, with the Inner Precinct of St John’s Priory above. This is the area that now forms St John’s Square. Just above the number 12 on the map, to the left of St John’s Lane can be seen one of the large houses and gardens that once lined the street leading up to the gate.

I wrote about Albion Place a few weeks ago. This street runs from St John’s Lane through what was the Outer Precinct.

The Dissolution of the Monasteries marked the end of the Order of the Hospital of St John of Jerusalem (apart from a very brief resurrection during the reign of the Catholic Queen Mary I between 1553 and 1558). The original Order continues to this day, headquartered in Rome.

From the 12th century, the original Order had been shifting through southern Europe as military success and loss forced a change. After the loss of Jerusalem, they moved to Acre, then through Cyprus, Rhodes, Malta and finally Rome.

The last prior of the Order in Clerkenwell was William Weston. He appears to have been in favour with Henry VIII for cooperating with the handover of the Clerkenwell priory and was awarded a significant pension of £1,000 a year, however apparently he died on the day that the priory was taken by the Crown.

Over the following centuries, the Gate was used for a number of different purposes.

After the dissolution, the Inner Precinct appears to have been occupied by the Crown’s Office of Tents and Revels, with the rooms of the Gate being occupied by Crown officers.

The building began an association with the printing trade in the 1670s when a printing press was established in the Gate. Matthew Poole wrote a significant commentary on the bible whilst living in the Gate in the late 1660s and 1670s.

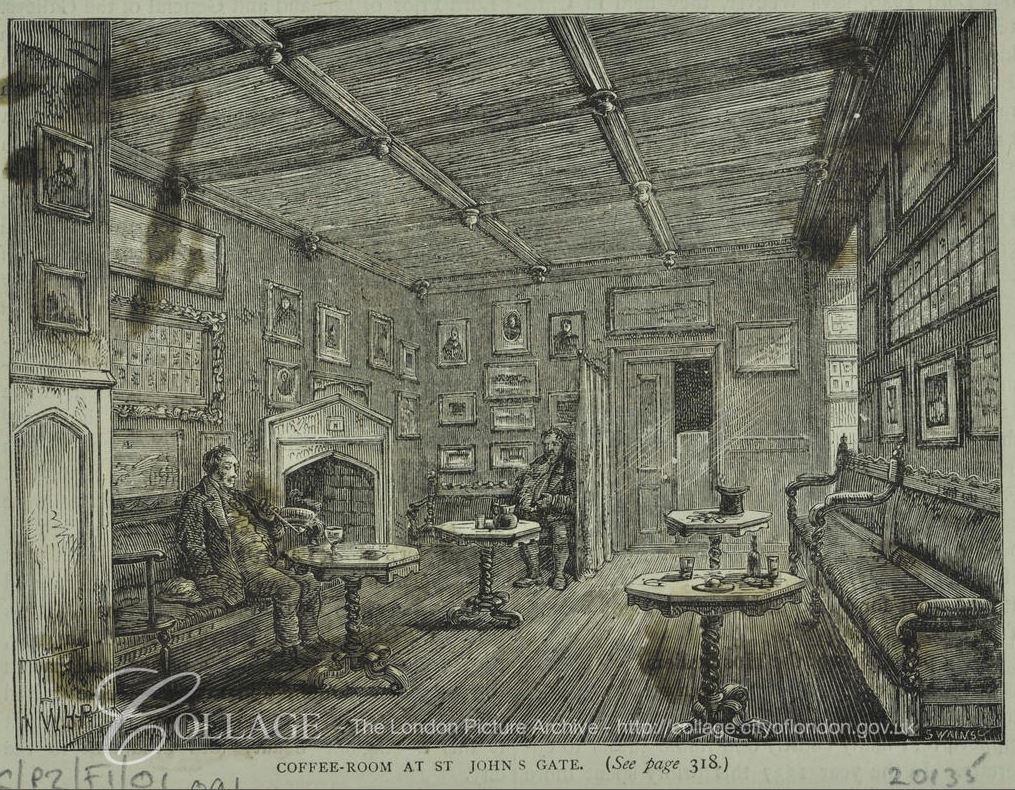

Richard Hogarth, the father the artist, opened Hogarth’s Coffee House in the Gate at the start of the 18th century. His unique selling point for the coffee house was that it was a place for gentlemen to meet and converse in Latin. It continued as a coffee house through the 1720s, but under different ownership and later became part of a tavern – the Jerusalem Tavern.

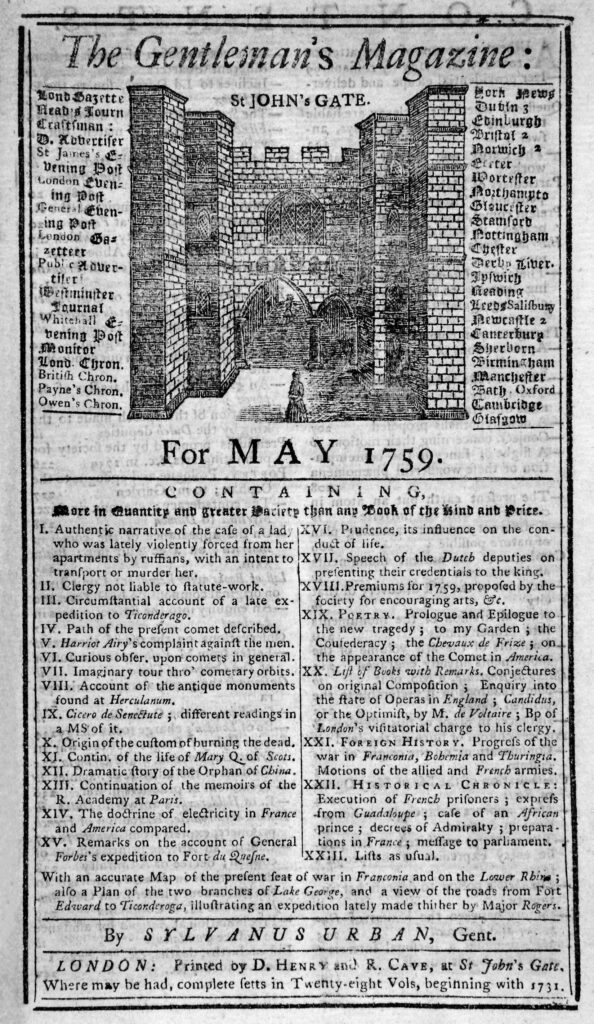

By 1730, one Edward Cave was living at St John’s Gate and it was from here that he established the Gentleman’s Magazine.

The Gentleman’s Magazine used an image of the Gate on its title page, and Edward Cave went so far as to use the image of the gate on the side of his coach, rather than a coat of arms:

Dr Johnson had a small room in the Gate during the publication of the magazine to which he was a contributor whilst also working on one of the best known early editions of the English Dictionary.

Cave died in 1754 and the Gentleman’s Magazine ended publication from St John’s Gate in 1781.

Throughout the rest of the 18th and first half of the 19th century, the Gate went through a number of different uses including being used for storage and providing space for a parish watch house.

By the 1840s, St John’s Gate was in a serious state of repair, and was considered a dangerous structure, and the new Metropolitan Buildings Act enabled an order to be served on the owners of the gate that it had to be either repaired or demolished.

An appeal was made for funds to restore the Gate, but this met with limited success. The City Press of March 16th 1861 reported that: “In 1851 the gate was threatened with total ruin. Repairs were essential to keep it standing. Mr W. Petit-Griffith proposed a subscription for its restoration. This unfortunately he failed to effect; yet with the aid of a few lovers of antiquity, he was able to strengthen the defective portion of the structure, and avert the ruin which seemed inevitable”.

During the mid 19th century, the history of the Gate seems to have attracted a number of societies who would use the large room directly above the arch. The St John’s Gate Debating Society met regularly at the Gate, although in newspaper reports of their meetings there seems to have been more “toasting” than debating. The Gate was also used by the imaginatively named “Friday Knights” as a meeting place – it does seem to have attracted a number of Victorian societies attempting to recreate a link with the medieval foundations of the Order.

The main change to the recent history of St John’s Gate was during the later part of the 19th century when it became the home for a modern version of the Order of St John.

The Victorian workplace was a highly dangerous place and accidents were common, with limited protection for workers and only extremely basic healthcare.

William Montagu, the 7th Duke of Manchester, Sir John Furley and Sir Edmund Lechmere identified a need for an organisation that would provide medical support for workers. They formed the modern Order of St John, and it was granted a royal charter by Queen Victoria to become a Royal Order of Chivalry.

Edmund Lechmere purchased St John’s Gate to be used as the headquarters of the new order, and an extensive series of renovations were carried out.

In 1877, the Order formed the St John Ambulance Organisation, who provided training and first aid equipment. This led to the founding of the St John Ambulance Brigade as a volunteer organisation, trained and equipped to provide medical support.

As well as restoring the main gate, the late 19th century restorations included the construction of a new building, in a similar style and joined to the gate, along the eastern edge of St John’s Lane.

In the following photo, the Gate is to the left, and the new extension to the Gate is visible, with a large door at ground level, sized to take ambulances of the St John Ambulance Brigade.

Returning to the Gate, and there are a number of shields above the arch:

These are, from left to right:

- the arms of Henry VII who was the King at the time the Gate was built

- the arms of Edward VII, the 1st Grand Prior of the modern order

- the arms of Queen Victoria, the 1st sovereign head of the modern order

- the arms of Prince Albert, Duke of Clarence, Edward’s son

- the arms of Thomas Docwra who was responsible for the rebuild / construction of the Gate in 1504

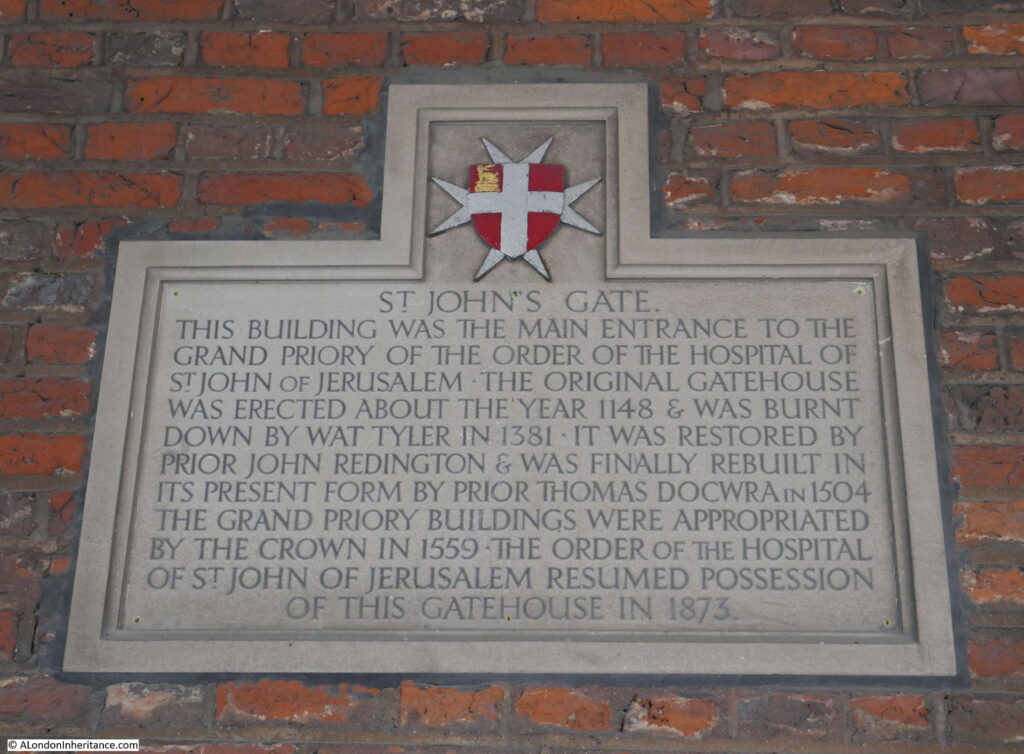

Walking through the arch in the Gate, and there is a plaque on the wall which gives some additional detail on the history of St John’s Gate:

The plaque refers to the original gatehouse being burnt down by Wat Tyler during the Peasants Revolt. There is now some doubt as to whether there was much destruction at the Priory during the Peasants Revolt, however the Prior at the time did come to a sticky end.

The Prior was Sir Robert Hale (also written as Hales), known as Hob the Robber for his collection of the Poll Tax through his role as Lord High Treasurer. The unfairness of the Poll Tax, where the tax was the same for any individual regardless of their ability to pay, provoked the Peasants Revolt in 1381.

Looking for Hale, the rebels camped on nearby Clerkenwell Green and possibly ransacked part of the priory. Hale had taken refuge in the Tower of London along with the Archbishop of Canterbury, Simon Sudbury. They were found in the tower by the rebels, carried out to Tower Hill and beheaded.

Walking through the arch, up to Clerkenwell Road and we can view St John’s Gate from the north:

The Gate would have once presented a more imposing appearance with a taller archway.

Over the centuries, the road has been heightened by around three feet. Evidence for this can be seen in two doors on either side of the northern side of the gate (in the side towers so not visible in the above photo).

The doorway on the eastern side appears to be much smaller or part buried in the ground:

The doorway on the opposite side is full height:

The full height doorway was rebuilt in 1866 with the door on the opposite side left in its half buried position.

Photos and prints of St John’s Gate show how the Gate and surroundings, have changed over the years. The following photo is from the late 19th century publication “The Queen’s London” and shows the southern face of the Gate from St John’s Lane.

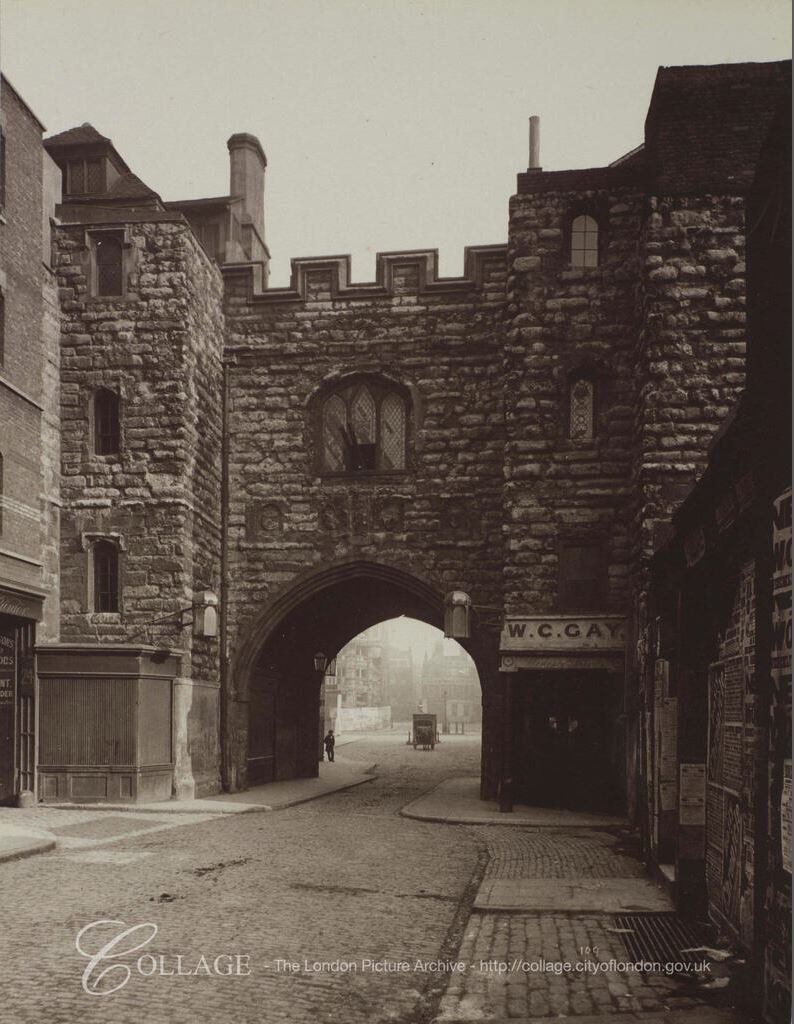

Another photo of the Gate, dated 1885, and looking through towards Clerkenwell Road.

Image credit: London Metropolitan Archives, City of London: catalogue ref: p5369514

Underneath the name sign W.C. Gay are the words Wines and Spirits, indicating the type of business that occupied the Gate during the 19th century.

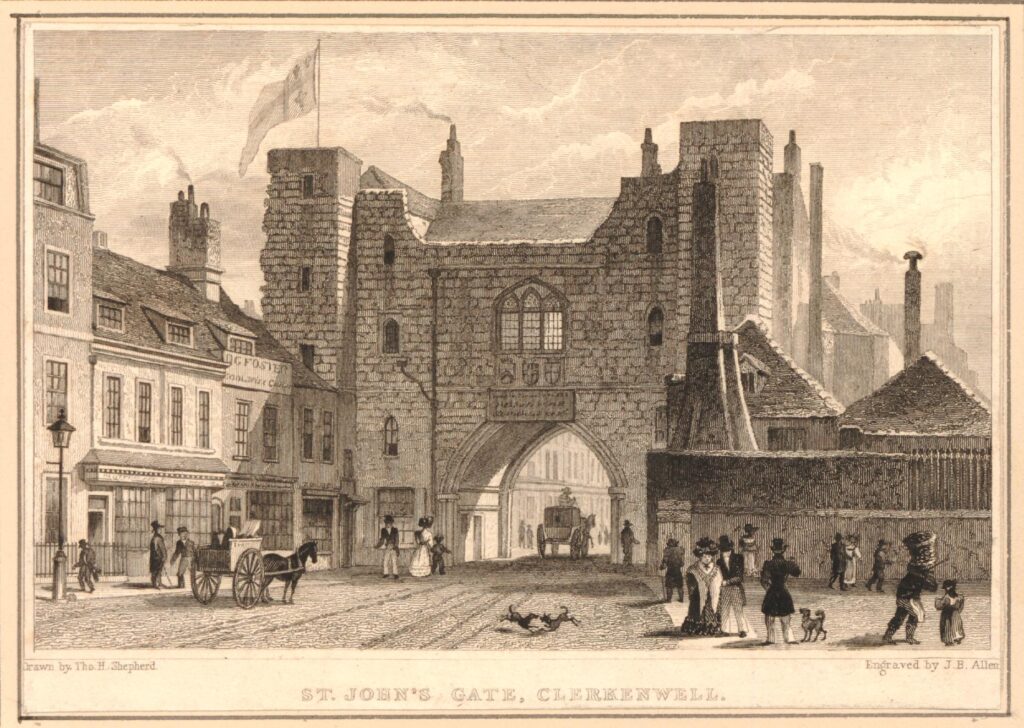

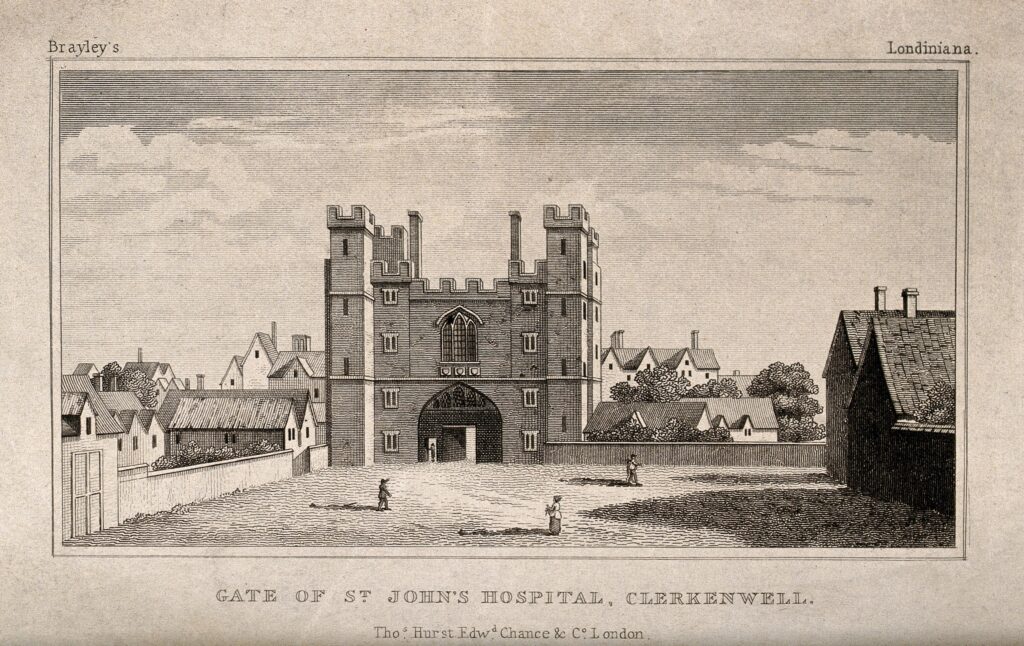

The south face of the Gate in 1829 (©Trustees of the British Museum):

All these photos and prints show the archway through the Gate being open for traffic. Today, bollards prevent any traffic passing through, with the route being for pedestrians only. The gate was closed for traffic due to the narrow width and low height of the arch sides, as well as the potential for damage to the Gate from the vibrations caused by traffic passing through.

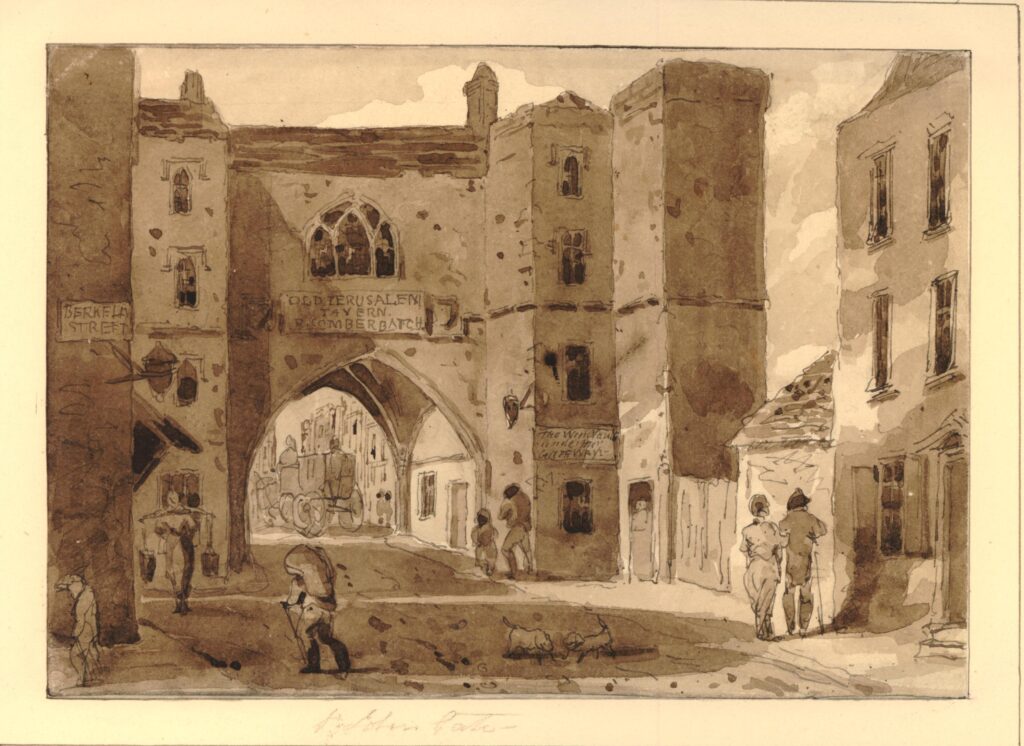

The following drawing dates from 1720, and again shows the south side of the Gate, facing St John’s Lane (©Trustees of the British Museum):

The 1504 rebuild of the Gate by Thomas Docwra had included crenellations, or battlements along the top of the gate, however as shown in the drawing above, by 1720 these had been removed and a more traditional sloping roof had been installed, presumably to provide the room at the top of the Gate with additional height and roof space.

The sign above the arch reads “Old Jerusalem Tavern – R. Comberbatch”, from the days when a tavern occupied the Gate.

The following print is one of the earliest views of St John’s Gate. After Wenceslaus Hollar, the print is from the mid 17th century, and shows how impressive the Gate must have been before the construction of the buildings of St John’s Lane and Square which would later crowd around the gate.

Credit: Gate of the Hospital of the Knights of St. John of Jerusalem, Clerkenwell, London, surrounded by thatched domestic buildings. Engraving after W. Hollar. Credit: Wellcome Collection. Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

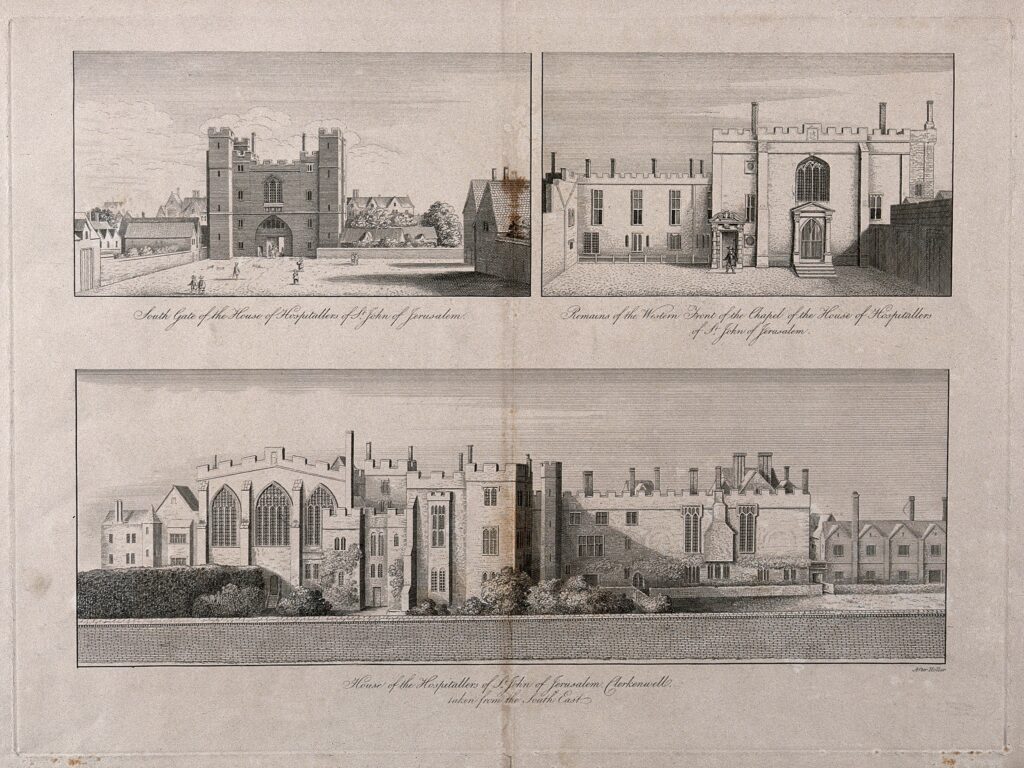

The following print, also after Hollar and from the mid 17th century, show some of the surviving buildings of the Priory:

Credit: Hospital of the Knights of St. John of Jerusalem, Clerkenwell, London. Engraving after W. Hollar. Credit: Wellcome Collection. Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

The views are looking from the south east of the Gate and as well as the gate, show the (top right) remains of the western front of the chapel of the House of Hospitallers of St John of Jerusalem, and (lower illustration), the main House of Hospitallers of St. John of Jerusalem.

The print gives a very good impression of how impressive the buildings of the Priory must have been.

As mentioned earlier in the post, one of the activities that took place within the Gate was a coffee house, with Richard Hogarth being the first proprietor of such an establishment, and the following print shows a coffee-room in St John’s Gate:

Image credit: London Metropolitan Archives, City of London: catalogue ref: SC_PZ_FI_01_091

Although an early 16th century reconstruction, St John’s Gate is still a tangible link with the medieval priory that once occupied 10 acres of land in Clerkenwell. We can still follow the boundaries of the Priory in the streets of Clerkenwell and see where the inner and Outer Precincts were located.

St John’s Square is home to the Priory Church of the Order. A post war rebuild following wartime destruction of the earlier church, however below the church is a crypt with some evidence going back to the 12th century.

St John’s Gate is still home to the modern Order of St John, and the St John Ambulance Brigade which continue their work to this day, and, and during the current pandemic, the organisation has taken on its biggest mobilisation during peacetime.

There is a museum in St John’s Gate and tours are given of the building. Although closed at the moment, St John’s Gate is well worth a visit to discover an intriguing part of London’s history.

There’s a pretty little 1950s mini office tower opposite whuch is an early work by the (in)famous Richard Seifert… and the BBC’s newspaper drama series Press was shot there and around.

Is the present Docwra building company related to Thomas of 1504 I wonder? An unusual name from the north of England I think

The Wikipedia entry states: “Docwra, also with spelling Dockwra, Dockwray, Dockray and other variants, is an English language surname, of Norse-Viking origin, which was significant in London and East Anglia in the 17th century.”

Fascinating treatment of this treasure. Thanks. The coffee room illustration was a particular treat. I love that the earlier coffee house is connected to Hogarth’s family.

As a child I lived in Penny Bank Chambers on the corner of Clerkenwell Road and St. John’s Square. Both my mother and aunt were cleaners in the gate so I often played inside while they scrubbed the worn down stone staircase.

Very interesting article today.

My wife and I thoroughly enjoyed our visit to this museum about 18 months ago – you have to book but it’s well worth it as the guides take you around the maze of exhibits, staircases and corridors – explaining the history en route – we had lunch at The Crown on Clerkenwell Green afterwards – altogether a lovely trip out

What an interesting article. Thank you Tony

Great read as usual.

Week after week you give us such interesting reads,Admin. This was yet another. It beats me just where you find the time for all the research!

So glad to be ‘back on the list’, did you ever find out what had happened to the e-mails last week?Perhaps some of this gloomy damp weather got into the systems.

Another very impressive and most interesting article.

I remember going to St John’s gate to get my collar badges, buttons and white haversack (HA 1) for my St John Ambulance Brigade uniform. A magnificent structure, and a fantastic article.

Thank you very much. This small area of London has provided me with numerous fascinating routes from Farringdon Station to Charterhouse Square, until recently the home of the Society of Genealogists. There’s still a hospital in the area, without official public access.

Fascinating reading! On Facebook there’s a Group called Gate Appreciation Society where a member posted this gate, so I Googled and found your treatise! So, planning to visit when I’m in London.

In your article you mentioned a link with printing

There was an underground tunnel from the priory to the priory press in St jonlhns square long since bricked up. But in the seventy when it was still an active printing shop there was still the trapdoor in the shop which led to the tunnel