Before heading to St Saviour’s Dock, a quick thank you for ordering tickets for this year’s walks. At the time of writing, the Barbican walks and Wapping walks are sold out. Many of the Bankside dates have sold out, but there are some tickets remaining on later dates, and there are a few on the Southbank walks.

St Saviour’s Dock is an inlet from the Thames in Bermondsey, just to the east of Tower Bridge on the south bank of the river. We can look across the river near Hermitage Moorings on the north bank, and see St Saviour’s Dock just to the left of Butlers Wharf.

I have circled the location of St Saviour’s Dock in the following map (© OpenStreetMap contributors):

Cross over to the south bank of the river, and on approaching the dock, there is a walkway spanning the entrance:

View from the footbridge across to the north bank of the river, at low tide, with thick mud across the foreshore:

Looking along St Saviour’s Dock – a carpet of mud:

St Saviour’s Dock is a very old feature of this section of the river. Originally the mouth of the River Neckinger, although it is very hard to pin down exactly where the Neckinger ran with any certainty, and how much of the water course was a natural river.

There were many streams and ditches in this area of Bermondsey and much of the land was low lying marsh. Some of the ditches which may have once been part of the Neckinger can be seen on 18th century maps, which I will come to later in the post.

Looking south along St Saviour’s Dock, the bends in the dock give the impression of a natural feature. Early maps show the sides of the dock as relatively straight, so the curves we see today may have been the result of extending some of the warehouses that line the dock as an attempt to maximise warehouse space.

At the far end of the dock, it comes to an abrupt halt at “Dock Head” at the junction of Jamaica Road and Tooley Street.

It is impossible to know for sure as to the origins of St Saviour’s Dock. It appears to have been part of the lands of Bermondsey Abbey, and what was then a natural watercourse, had banks created on either side, and a mill built on one side of the dock by the abbey at some point around the 13th century.

Just to the east of St Saviour’s Dock is Mill Street, apparently named after a mill stream which ran along the route of the street and which powered the mill, which was used to grind corn for the abbey. Mill Street is on the other side of the warehouses that line the eastern side of the dock, so is very close and complicates the mapping of waterways in the area.

The land around St Savoiur’s Dock was fully developed between the 16th and start of the 19th centuries, as maps from the 17th and 18th centuries confirm.

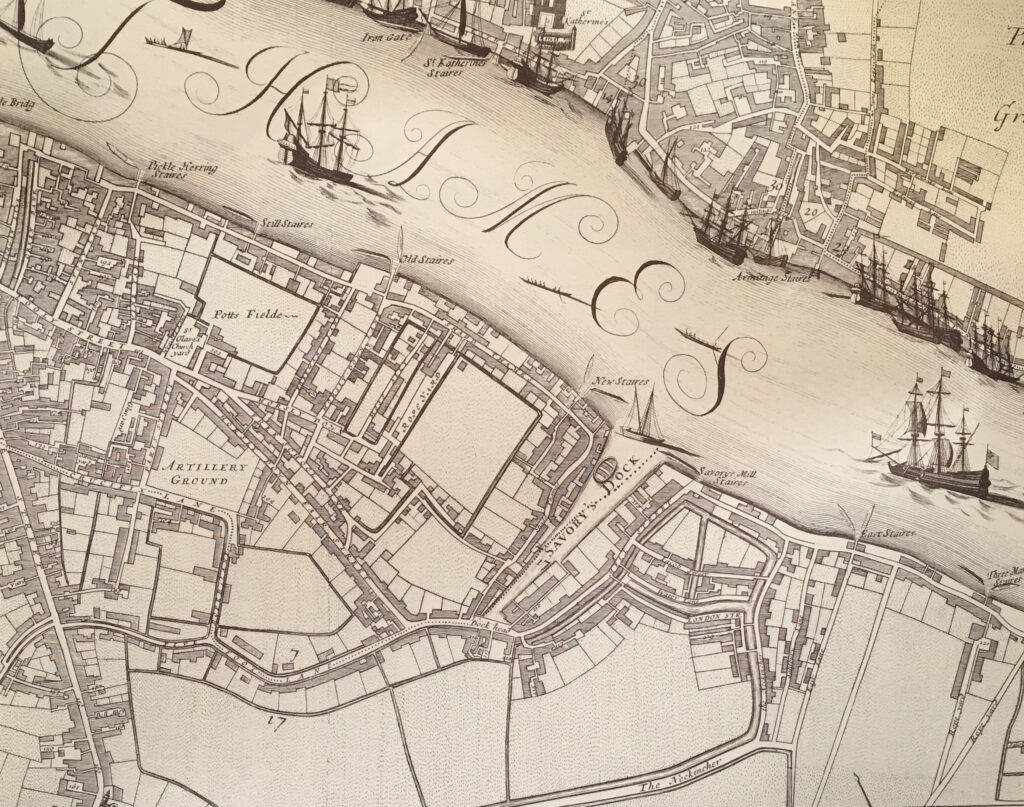

The following is an extract from William Morgan’s map of London from 1682. St Saviour’s Dock is located just to the lower right of centre of the map:

Note that the name of the dock in the map is Savory’s Dock. This may be a simple corruption of the name, or it could have been a rather sarcastic description of the dock given that there was much pollution from the surrounding buildings, and Bermondsey’s growing industry, that ended up in the dock.

I like the depiction of a small boat in the dock. It looks too wide to be a waterman’s boat, and could have been a lighter that transported goods between boats moored in the river and the warehouses lining the dock.

By the time of Morgan’s map in the late 17th century, it appears that buildings were lining the majority of the dock, and streets had been built to the east.

If you click on the above map to enlarge, you can see that to the right of St Saviour’s Dock were a number of water channels, and that to the lower centre edge of the map, there are what appear to be two water channels either side of a road, with a name of “The Neckincher” along the street. presumably this name applies to the water channels, and is a version of the name Neckinger.

This is the problem with being sure as to the route of the Neckinger, and how much of the route was a natural feature, and how much were artificial channels and ditches used to perhaps provide water to the industries in the area, or to drain what was low lying, marshy land.

Seventy three years after Morgan’s map, a 1755 map has St Saviour’s Dock on the edge of the map, with the surrounding area looking much the same as in 1682:

It is interesting that the name Savory Dock was again used on this later map. This name does not appear to be used when reporting anything about the dock in newspapers. For example on the 10th of January 1730, the Kentish Weekly Post used the name Saviour in a report that “Last Sunday, a Man, well dressed, was found drowned in St Saviour’s Dock”.

I can find no newspaper reference to the Savory spelling of the dock’s name.

Newspaper’s do give us an idea of the type of businesses and properties that surrounded the dock in the years around the publication of the above map. For example, on the 11th of January 1762 there was a report of a fire in one of the buildings along the dock:

“Thursday morning a fire broke out in a granary belonging to Mess. Hemmock and Co. Corn Lightermen, at St. Saviour’s Dock, near Dock Head, which was consumed, together with 8 dwelling houses, and a great many warehouses, and other out-buildings; three other dwelling houses were greatly damaged. Mr Allport, a biscuit maker, and his family, ran into the street almost naked, not having time to save anything. It being low-water, it was with difficulty a whole tier of ships was preserved, as they lay upon the mud close to the Dock, and nothing parted them from the flames but a crane house, which took fire several times, but by the activity of the firemen was prevented from getting to a head. We hear no lives were lost.”

So in 1762, St Saviour’s Dock was surrounded by a granary, dwelling houses, and a great many warehouses, which does align with the view presented in the above maps. As well as the granary, there are also mentions of a “Mr John Robinson’s Rope Warehouse” in the dock in the mid 18th century.

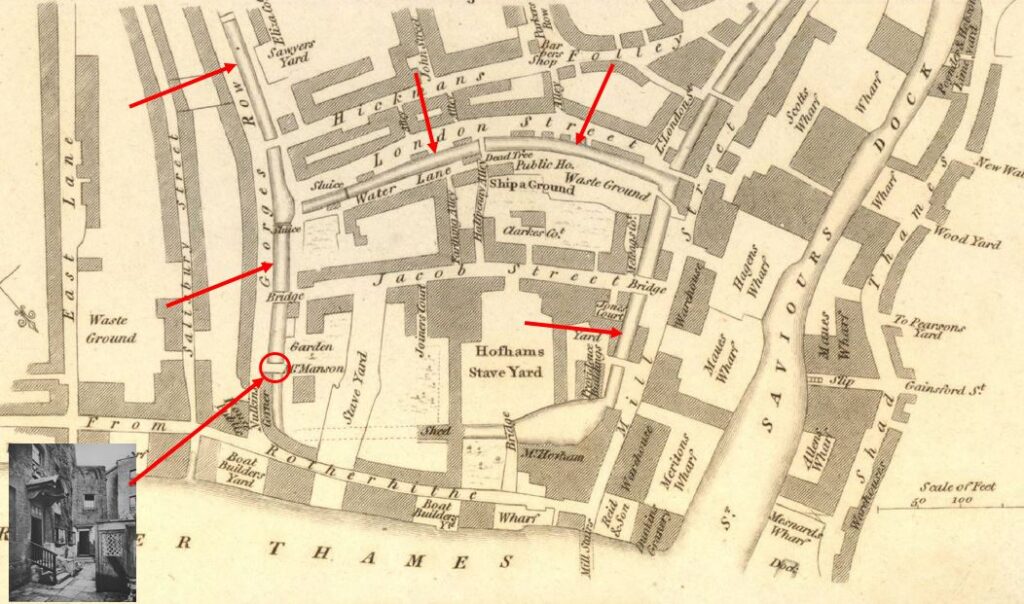

The following map is dated 1813 and includes the names of the wharfs along the dock. Only two also have the names of products stored, with a granary at lower left of the dock and a lime yard at upper right.

What is interesting about the above map is the area to the left (east) of St Saviour’s Dock.

On this map there are a number of streams / ditches shown, along with bridges over these. I have highlighted the waterways with arrows.

The area between the waterway on the left and St Saviour’s Dock is the area that would become known as Jacob’s Island (after Jacob Street running through the centre). It was Charles Dickens who would bring some notoriety to this small patch of Bermondsey when he apparently located Fagins den and Bill Sykes death in Jacob’s Island in his novel, Oliver Twist.

In the lower left of the map, I have included the photo of Bridge House, a house that was built over one of the bridges (arrowed). I have researched and written about the location of Bridge House in my post “A Return To Bermondsey Wall – Bevington Street, George Row And Bridge House”.

The above map does confirm that the area was still a place of ditches and streams in the early 19th century, all possibly once part of the Neckinger, but would disappear during the rest of the 19th century as new warehouses and roads were built. The ditches do not appear to have any connection to St Saviour’s Dock or the River Thames, so must have just held stagnant water.

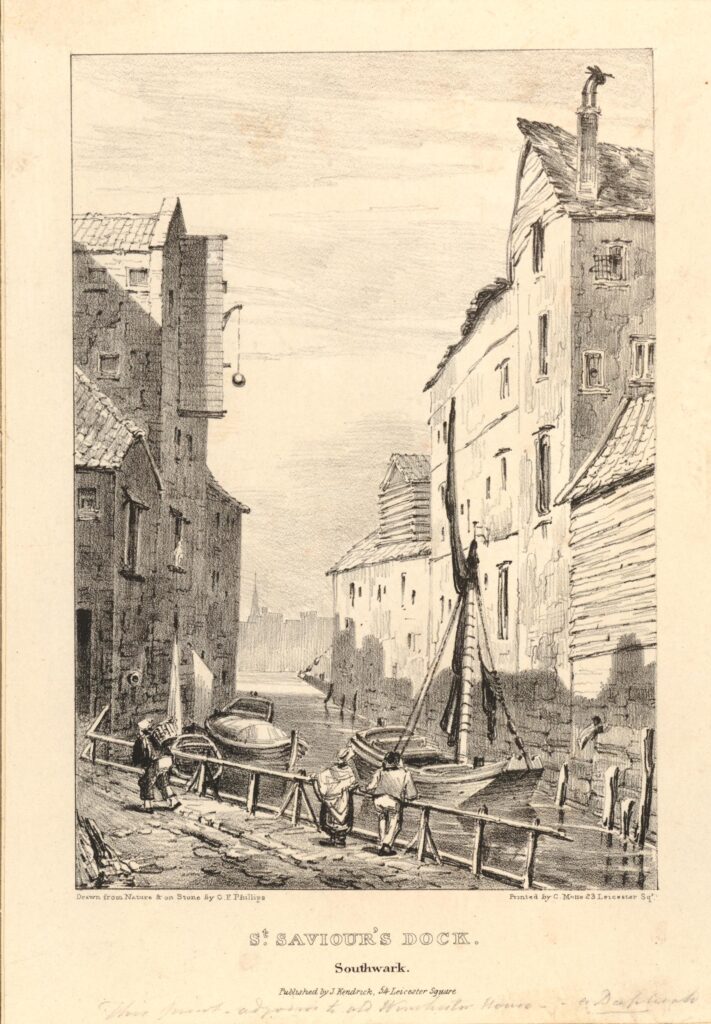

The following print shows a view of St Saviour’s Dock around 1840 – but the print is not quite what it seems (© The Trustees of the British Museum):

Underneath the name St Saviour’s Dock is the name “Southwark” rather than Bermondsey. The above print is really of the dock just to the north west of Southwark Cathedral, where the replica of the Golden Hind is now located.

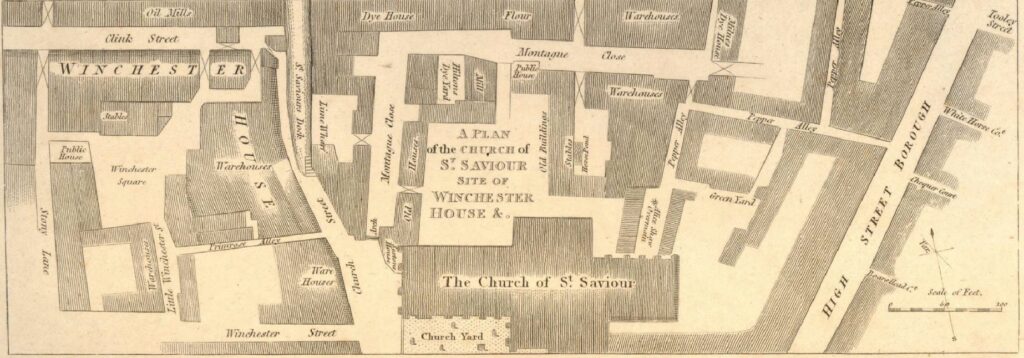

Southwark Cathedral was originally the church of St Mary Overie. The church was renamed St Saviour’s at some point around the Dissolution of the Monasteries in 1539, and this name would remain in place until 1905 when it became Southwark Cathedral.

The small dock just to the north west of Southwark Cathedral was originaly Mary Overie Dock, but with the renaming of the cathedral, the dock took on the name of St Saviour’s Dock and is shown with this name in Rocque’s map of London from 1746, and in this 1811 print which shows the church of St Saviour (Southwark Cathedral) at lower centre, and St Saviour’s Dock to upper left.

The 1895 OS map continues to show the Southwark dock as St Saviour’s Dock.

So there were two St Saviour’s Docks, and we need to be careful with references to the name. Today the Southwark dock is the location of the Golden Hind replica, and the address on the Golden Hinde’s website is back to the original name of St Mary Overie Dock.

The 1895 Ordnance Survey map of the Bermondsey St Saviour’s Dock shows that the dock was lined with warehouses, wharfs and factories, including a flour mill, coal wharf, packing case factory and lime wharf – the typical mix of industries that you would find along any stretch of the industrial Thames in the 19th century.

As with so much of the London docks, St Saviour’s Dock went into decline after the war. Warehouses located down a narrow inlet just were not suitable for the size and type of ships, and containerisation would kill off any hope of using warehouses such as those found in the dock.

St Saviour’s Dock remained as an open inlet to the Thames, but the buildings along the edge of the dock started a path to dereliction.

St Saviour’s Dock has been used in a number of films. One of these in the years before the buildings were transformed is Derek Jarman’s 1978 film Jubilee.

Jarman lived for a time in Butler’s Wharf, between the dock and Tower Bridge, and the film, which is still available as a DVD, whilst a typical Jarman film and very much of its time, is good to watch for one interpretation of punk and the late 1970s, but also for some London location spotting.

In the following clip, the characters Bod, Mad and Chaos are about to throw a body over the side of St Saviour’s Wharf, to the mud below, with the empty warehouses in the background:

From the 1980s onwards, the majority of the wharfs lining St Saviour’s Dock would be converted to apartments and offices. A walk along the side streets that follow the dock to the east and west reveals how many have survived.

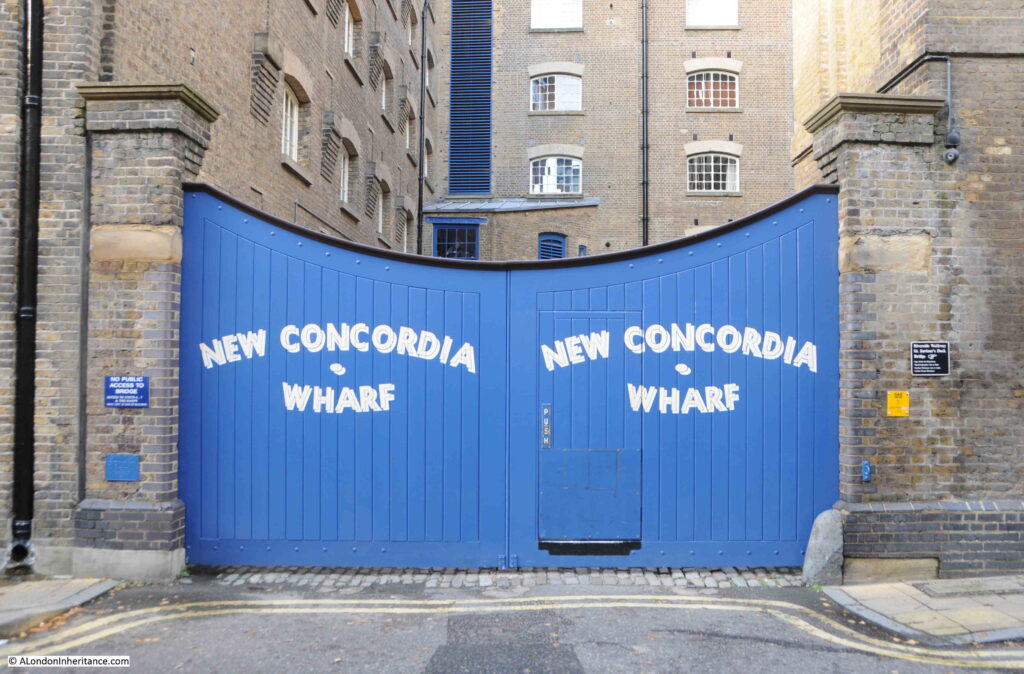

Starting in Mill Street which runs along the eastern side of the dock, and to the north east corner is New Concordia Wharf:

New Concordia Wharf was originally built in 1882 as St. Saviour’s Flour Mill, however after one of the fires that seemed to be a frequent risk to the wharfs along the river, it was rebuilt between 1894 and 1898.

St. Saviour’s Flour Mill / New Concordia Wharf included a flour / corn mill, continuing a tradition of milling flour that goes back to the original mill built on the banks of the dock by Bermondsey Abbey in the 13th century.

Rather than being powered by water, the mill was steam powered, and the water tank and chimney remain, although the water tank has been somewhat hidden by changes to the roof of the building.

The chimney was truncated in 1979, and now looks rather ungainly with what appears to be a concrete slab on the top of the chimney, but is still an unusual sight on the end of a warehouse.

Conversion of New Concordia Wharf to apartments was carried out between 1982 and 1983 and was one of the first examples of the warehouse conversions that would become the standard for the type of building along the Thames.

We then come to Grade II listed St. Saviour’s Wharf:

St. Saviour’s Wharf was built in 1868, and was for sale by auction in 1870. The advert for the auction provides some details of this 1868 building:

“Saint Saviour’s Sufferance Wharf, together with the modern pile of warehouses in Mill Street erected in 1868 in the most substantial manner under the superintendence of an eminent architect and so arranged as to fulfil all the requirements of the Metropolitan Buildings Act and of the Fire Insurance Companies. The premises comprise three double warehouses each with five floors and basement, having a frontage of 117 feet next Mill-street.

The various floors are carried on columns from basement to roof, and are strongly timbered. The ground floor is asphalted. The party walls are 2 feet 3 thick, and there is no communication between the three warehouses, except on the basement.

There are two staircases to each warehouse, and loophole doors and windows on each floor fronting the land and waterside.

The floors of two of the warehouses are divided by brick walls 2 feet 3 thick, communicating by chambers, enclosed by wrought iron folding double doors.”

The details of the construction of the buildings were important for potential buyers. Not just to show the strength of the building, but also that the building was designed to limit the spread of fire.

Fires in warehouses were a continual risk. Buildings on top of each other, all crammed with highly combustible goods resulted in frequent fires, and the newspapers almost always had reports of fires in warehouses along the Thames (for example, see my post on the “The Great Fire at London Bridge”).

No idea what the purchaser of St Saviour’s Wharf paid for the buildings, however today, a 2 bedroom apartment is for sale at £1.2 million.

The view along the southern end of Mill Street, with more wharfs and warehouses. Unity Wharf nearest.

Unity Wharf is Grade II listed and is now mainly office / commercial space. In the 1953 publications “London Wharves and Docks”, Unity Wharf is listed holding Canned and Cased Goods, Bagged produce and General.

To the side of Unity Wharf is the entrance shown in the following photo:

It was gated half way along on my visit, but appears to be one off, if not the only passage through the wharfs to the side of St Saviour’s Dock.

In the 1895 Ordnance Survey Map, the passage is shown, and marked as “Free Landing Way”, which I assume meant that it could be used by anyone to land something by boat in St Saviour’s Dock, and the passage provided a route between water and Mill Street. I would have loved to have got to the end of the passage and looked over the edge into the dock.

At the end of Mill Street, we reach the junction of Jamaica Road and Tooley Street. In the following photo, the steps to the left of the red bins lead up to the wall at the very end of St Saviour’s Dock – the point labeled Dock Head in the 17th and 18th century maps earlier in the post.

Climb the steps, look over the wall, and we can look down on St Saviour’s Wharf:

Towards the northern end of the dock where it meets the River Thames and is spanned by the footbridge:

We can now walk along Shad Thames, the street that runs along the wharfs on the western edge of the dock.

The buildings have a couple of footbridges between the wharfs on the right and additional warehouse space on the left. These were used to transport goods between buildings without having to travel up and down floors and across the street, although looking closely at one of the bridges, I doubt these are original, they look either very good restorations or new copies of what would have spanned the street.

The following photo shows the “B” warehouse of St Andrew’s Wharf:

This building dates from 1850 and is Grade II listed, but as can be seen by the changes in brickwork, it has been partially rebuilt a number of times, most recently when it was converted for residential use.

We then come to the point in Shad Thames where it leaves the wharfs that line St Saviour’s Dock, and turns west to head towards Tower Bridge.

At this corner point is the much rebuilt and restored Butler’s Wharf:

And that brings me to the end of a look at St Saviour’s Dock, and the wharfs and warehouses that line this ancient inlet from the River Thames.

Although the buildings have been converted to residential and commercial, they do still provide a really good impression of what the dock would have looked like from the late 19th century onwards.

The thing that is missing is noise and activity. Walking the area today and it is quiet. No lighters in the dock, no goods being loaded and unloaded and very few people walking the streets.

The dock itself is always thick with mud, and I have never seen anyone searching the dock or foreshore. A good thing as it looks highly dangerous, but intriguing to imagine what is buried beneath the mud given the centuries of use of St Saviour’s Dock.