The following photo was taken by my father from the south bank of the river, looking across to the north bank, it is where the walkway along the river turns slightly inland to pass under Southwark Bridge:

The same view today:

The layout of the place is the same today, with the pillars (although today much more substantial) supporting the building overhead, being in the same place. The building on the left is now a Zizi Italian restaurant, replacing the warehouses and industrial buildings that once lined this stretch of the river.

The view is across to the north bank of the river, where a number of warehouses can be seen. Of these, there is only one building that remains today. That is the large warehouse directly underneath the dome of St. Paul’s Cathedral.

The subject of today’s post, is a feature on the north bank, that is just visible in the above photo.

Whilst the warehouses form an almost continuous line along the river, there is one place where the river cuts slightly in land to form a small dock. This can just be seen to the right of the following enlargement from the above photo and is Queenhithe Dock:

The view across the river today. Queenhithe can just be seen as the indention in the river wall, just to the right of centre. The tall brick building to the left is the warehouse seen below the dome of the cathedral in the above photos:

A closer view showing Queenhithe Dock. The building at the back of the dock is a recently completed hotel:

Queenhithe’s importance comes from the fact that it is a surviving dock space dating back to the Saxon and Medieval period.

The dock is believed to have been established by King Alfred after he reoccupied the area within the City walls in 886. At that time, it was called Ethelredshythe after King Alfred’s son in law, when it was a place where boats were pulled up on the foreshore with goods being sold from the boats.

The name Queenhithe comes from Queen Matilda, the wife of Henry I, who was granted the taxes generated by trade at the dock. Hithe means a small landing place for ships and boats.

Matilda also had built London’s first public lavatory at the dock, which was available for the “common use of the citizens” of London, and was no doubt built at the dock so the output of the lavatory could flow directly into the river – some things do not change.

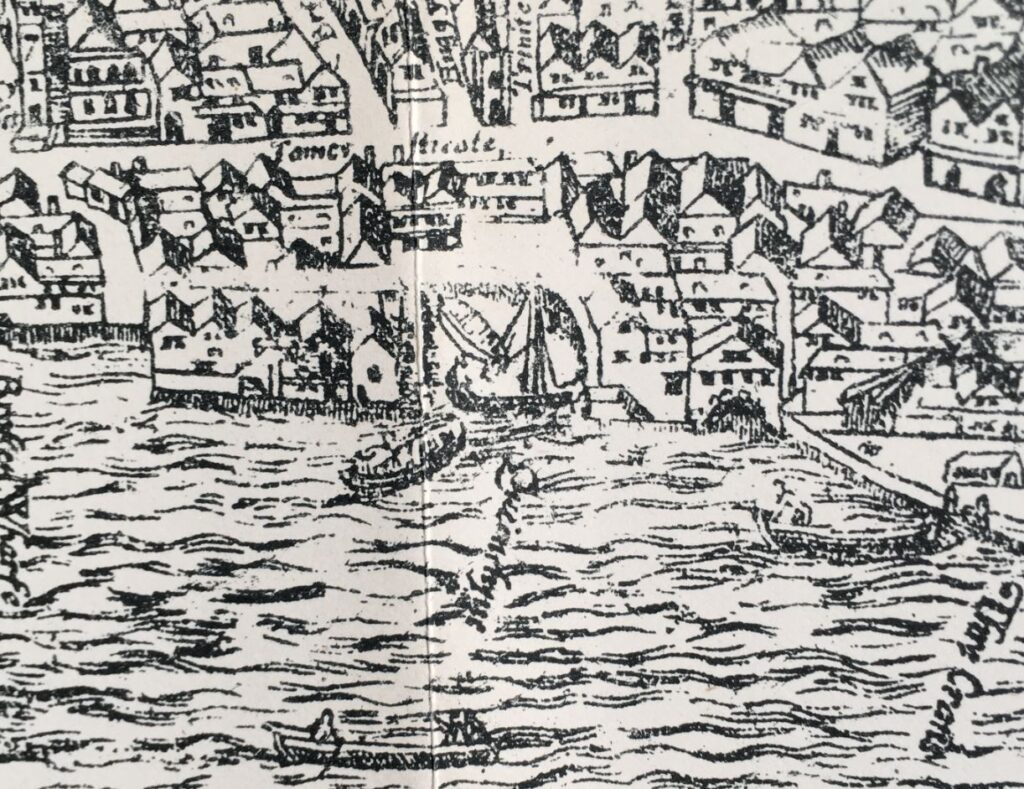

Queenhithe is shown in the Agas map (from around the mid 16th century to the early 17th century), with one boat with a sail, and a smaller boat being within the dock:

The map appears to show some open space between the end of the dock and the houses lining Thames Street, and this space was presumably used for holding cargos being moved between the ships on the river and the land, and for conducting sales.

Writing in London Past and Present (1891), Henry Wheatley describes Queenhithe as:

“It was long the rival of Billingsgate and would have retained the monopoly of the wharfage of London had it been below instead of above bridge. In the 13th century it was the usual landing place for wine, wool, hides, corn, firewood, fish and indeed all kinds of commodities then brought by sea to London.”

The dock today is a much smaller part of what was the original dock and trading area. Excavations beneath some of the buildings surrounding the dock have found remains of a Roman quay along with the 9th century shore where trading took place, along with a series of medieval waterfronts, showing how during the medieval period the river wall was gradually being pushed further into the river.

The edge of the dock as it enters the Thames:

Queenhithe is classed as a Scheduled Ancient Monument, and is one of the areas along the river where any form of mudlarking or disturbance of the dock or foreshore is prohibited.

“Quays are structures designed to provide sheltered landing places with sufficient depth of water alongside to accommodate vessels over part of the tidal circle. The features and complexity of quays vary enormously depending partly on their date but also on their situation and exposure, the nature of the underlying geology and alluvium, and the volume and types of trade they need to handle. By their nature, quays also tend to occur in proximity to centres of trade and administrative authority, usually in locations already sheltered to some extent by natural features. Basic elements of quays may include platforms built up and out along a part of the coast or riverside that is naturally deep or artificially dredged, or along an artificial cut forming a small dock on a riverside or coast.

Urban waterfront structures and their associated deposits provide important information on the trade and communication links of particular periods and on the constructional techniques and organisation involved in the development of waterfronts. Artefacts recovered through excavation and the deposits behind revetments will retain evidence for the commodities which were traded at such sites.

Major redevelopment schemes along the Thames in the past have meant that the site at Queenhithe Dock is a rare survival of a sequence of waterfront constructions dating from the Roman period. The timber quays, revetments and the occupation levels are well preserved as buried features. It will provide evidence for the riverside development of London including archaeological and environmental remains and deposits. These deposits will provide information about the river and riverside environment and, by extension, about the people who lived alongside and have used it. The site is of particular significance as one of the few early medieval docks recorded in London.”

At low water, the full extent of the foreshore within Queenhithe can be seen:

Queenhithe featured in a range of newspaper reports which help to give an idea of what life was like at the dock, and in London. Some examples:

3rd December 1741: “On Friday a wealthy Baker near Bishopsgate Street, was by two Money-Droppers, deluded into a Public House by Queenhithe, and there at Cards tricked out of above £100. Tis strange this stale Cheat should still prevail.”

According to the rather wonderful “The 1811 Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue” by Francis Grose, a Money Dropper was a cheat who would drop some money, and then pretend to find it in front of someone, who he would then entice into a pub to share in his good luck at apparently finding the money.

Once in the pub, the Money Dropper would then cheat or rob the person he had enticed into the pub out of any money they had on them, and with the Baker, it was £100, a considerable sum of money in 1741.

Interesting that in 1741 it was thought that the was a “stale” cheat, so must have been a method employed by cheats for many years before.

The Lord Mayor’s procession (now the Lord Mayor’s show), when the new mayor took office was once a very riotous affair across the City. Crowds, fighting, fatal accidents – all very different to today. A long account of the November 1774 procession included the following reference to Queenhithe: “A man was run over by a coach at Queenhithe, and killed. A boat was overset near Queenhithe Stairs by the Watermen attempting to row passengers nigh enough to see the Lord-Mayor take water, and, it is said, six people were drowned”.

A reference to Queenhithe in 1799 adverts headed “Important Inland Communication” highlights how, in the days before the railways, goods arriving or departing from the river around Queenhithe could transfer goods across the rest of the country.

The advert stated that “The Public are respectfully informed, that Goods are regularly conveyed from Queenhithe, London, to Newbury, and from thence o Andover and Salisbury, and also down the Andover Canal to Southampton, and vice versa”.

It cost 11d (old pence) to send a hundredweight (about 112 pounds or 50kg) to Newbury, 2shillings and 6d to Salisbury and 2shillings to Southampton.

The advert shows how in 1799 there was an integrated transport system to transfer goods between London and surrounding counties and towns, as it also states the company “affords a regular communication with the following market and borough towns, and their respective neighbourhoods: Amesbury, Blandford, Cranborne, Christchurch, Dorchester, Downton, Fordingbridge, Fareham, Gosport, Havant, Kingscleare, Lymington, Mere, Newport, Poole, Portsmouth, Ringwood, Romsey, Shaftesbury, Whitchurch, Wilton, Wimborne and Yarmouth”.

It is often overlooked that the success of London as a trading port and as a commercial centre was only possible because of an interdependent relationship with a complex transport network between London and the rest of the country.

It was no good if people or goods arriving in London could not travel to destinations across the country with reliability and with a reliable timetable and cost.

One of my many unfinished projects is mapping out all the 18th century coach routes out of London. It was a very extensive network, equal in its day to the train network we have today.

As well as a reliable transport network, another important factor in the success of trade along the river was transparency in the pricing of key goods, so a market could develop based on pricing transparency. Here again, Queenhithe featured in many newspaper reports on the previous day’s prices:

“The Price of Flour for Bread at Queenhithe, from 4s, 9d per Bushel, Second Sort from 4s 4d to 4s 8d per Bushel. Windsor Beans £8, 2s per Quarter. Common Ditto £2 per Quarter.”

Sometimes the flour brought up for sale did not always sell as in 1757: “Last week several Mealmen at Queenhithe loaded their barges with the Flour that they had brought up for Sale, and sent it back”.

A “Mealman” was the name given to those who traded in grains and flour.

In the following photo, I am looking across the Thames from the north east corner of the dock:

There was a very similar view in the book Wonderful London, published in the 1920s, which shows lighters moored at the entrance, and inside the dock:

The description that goes with the above photo reads “Old Queenhithe, Once The Principal Dock Of London Port – All that is left of Queenhithe is an indentation in the line of wharves backing onto Upper Thames Street. But this, with Billingsgate, once formed the Port of London. It was called by its present name in the reign of Henry II, but as a dock it is centuries older, for we first hear of it in 899 during Alfred’s reign. To encourage its prosperity taxes were levied on foreign vessels discharging cargo elsewhere in the city. By Stow’s time it had fallen into disuse. It is now used for floating lighters to the surrounding warehouses”.

Queenhythe as a trading dock gradually lost its usefulness as the size of ships increased and the docks grew along the river, both within the City of London, and along the rest of the Thames.

As shown by the Wonderful London photo above, it did continue to be a place where lighters could be moored, with the relatively flat bottom of the dock allowing a lighter to be settled at low water, rather than being moored in the river. Space along the foreshore would have been at a premium during the 18th and 19th centuries, and partly into the 20th.

The Wonderful London photo shows the bed of Queenhithe appearing to be a level layer of mud. Today. the bed of the dock is mainly stone, broken bricks and the other detritus that gets carried along the river.

I suspect that the mud has gone as there is no activity in the dock today, and the lack of moored lighters and shipping along the river has increased the flow of the river, which has led to erosion of the mud.

If you look at the dock today, it gives the appearance that the mud has been cleared, and the incoming tide has pushed some of the old dock surface, and rubbish from the river, up to a pile at the back of the dock. Even an old scooter looks as if it is now becoming part of the buried history along the river:

Along the eastern wall of the dock is the Queenhithe Mosaic, which provides “A timeline displaying the remarkable layers of history from Roman times to Her Majesty’s Diamond Jubilee”:

The mosaic was design by Tessa Hunkin and Southbank Mosaics created the installation in 2014, and next to the river, it starts with the first Roman invasion:

Then we see the first reference to Queen Matilda and Queenhithe:

And that Queenhithe was London’s Grain Dock, a role it still had in the 18th century:

Other key London events are included such as when St. Paul’s Cathedral was first built in stone, and when London became a Saxon town:

There is then the 19th century “Big Stink” and World War 2 and the Blitz, which damaged so much of the area surrounding Queenhithe:

And finally the Millennium Bridge and the Jubilee. The mosaic is mainly a timeline, although the Thames flows along the length of the mosaic and at the end. as well as covering events in 2012, we also see the river opening out into the estuary, and four turbines from the wind farms that have covered parts of the wider estuary:

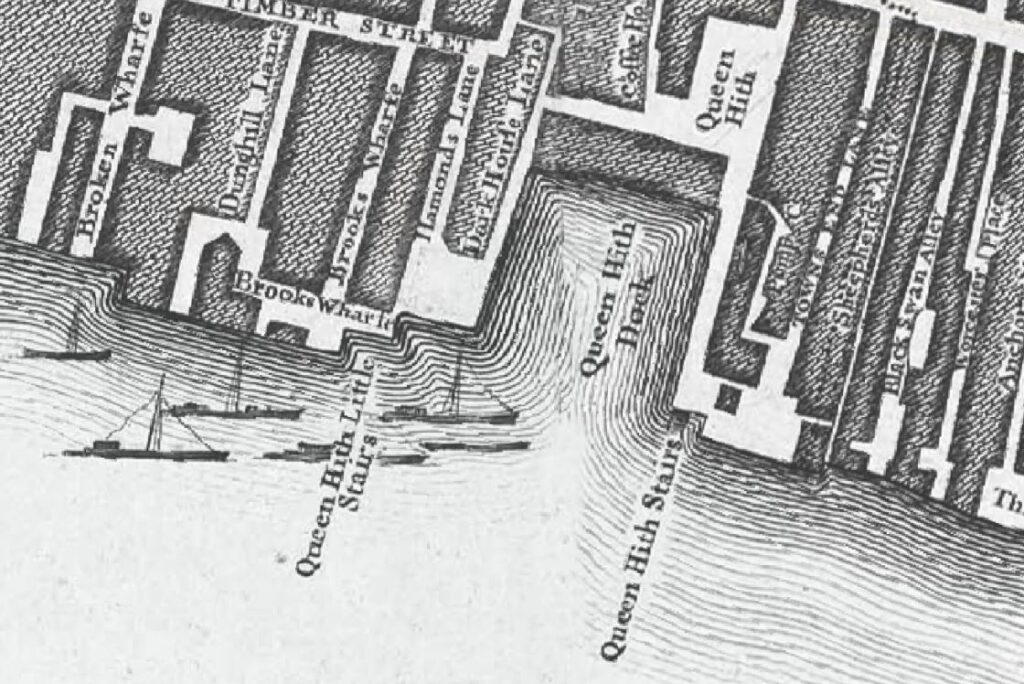

Rocque’s map of 1746 shows Queenhithe Dock with a small area of open space at the top of the dock, labelled Queen Hith (earlier references to the dock often spelt the Hith part without an e):

There are a number of boats which look as if they could be either sailing into, or away from the dock. There are also two sets of stairs. On the right are Queen Hith Stairs, and on the left are Queen Hith Little Stairs.

I can find a number of references to Queenhithe Stairs over the last few centuries. I quoted one earlier in the post with the story of the “boat was overset near Queenhithe Stairs“, when a Waterman was taking people out into the river to see the new Lord Mayor take to the river.

The Port of London Authority listing of all the steps, stairs and landing places on the tidal Thames does not have any reference to these stairs, however, they are still there. Not the nice set of stone steps leading down to a causeway on the foreshore, rather Queenhithe Stairs now consist of a vertical metal set of steps right up against the river wall, with a short set of steps providing access over the river wall as can be seen in the following photo, in exactly the same place as in the 1746 map:

Looking over the edge of the river wall, and we can see the vertical steps heading down to the foreshore:

There is a high river wall around Queenhithe, an essential bit of infrastructure to keep the surrounding land dry during times of very high tide, and building embankments along the river has been a continuous project in keeping the City of London dry.

I found a mention of Queenhithe Stairs in a reference to building an embankment wall, when in 1856 the London Weekly Chronicle had an article on an Act of Parliament to progress a whole series of infrastructure projects across London, including;

“An embankment along the Middlesex side of the River Thames, which said embankment will commence at or near certain stairs called Queenhithe Stairs, in the parish of St. Michael, Queenhithe, in the city of London, and from thence run in a westerly direction along and in front of the north bank of the river, and terminate on the river bank at or about a point in the parish of Saint Margaret in the City of Westminster, in the county of Middlesex.”

Other parts of the Act included building a railway within the embankment, so this was one of the enabling acts for both creating a new wall along the river and building what has now become the Circle and District underground railway lines along the Embankment.

The embankment as actually built ended at Blackfriars and did not extend to Queenhithe Stairs. The warehouses along the river, with their need for easy access directly onto the river prevented the new embankment being built as far as Queenhithe, but it is one of those “what ifs” with the development of London over the centuries.

From the walkway along the side of the river, there is nothing to be seen of Queenhithe Little Stairs, and I cannot find any written reference to the stairs, however looking across from the south bank of the river, we can see a set of steps vertically up against the river wall in the place shown in Roqcue’s 1746 map:

Interesting how there is a rise in the height of the foreshore around the bottom of the steps, and how these stairs survive despite having very little practical use these days, although I suspect that with the height of the river wall, having stairs along the foreshore is a sensible precaution for anyone stranded on the foreshore as the tide comes in, or having fallen in the river, although with the tides in the river, getting to the stairs would be a challenge.

Queenhithe is an interesting survivor, as what survives is the space, rather than any physical structure such as a building, wall, paving, etc. Whilst there are remains of the use of the dock below the surface, Queenhithe’s importance is as a reminder of how the City and the Thames developed and for so many centuries, were interdependent.

Given the level of 19th century rebuilding of the City, I am surprised that Queenhithe survived, and was not replaced by new warehouses, however the dock had already given its name to a Ward, so the importance of the place must have long been clear, and removing the place that was the source of the Ward’s name was probably too much, even for Victorian commercial redevelopment of the City of London.

The big warehouse is Globe Wharf; the plot behind it was the last undeveloped bomb site in the City proper (anotehr survived at Aldgate) until the 00s. The ‘new’ hotel is a reclad of an old building and Fur Trade House, an innovative and late warehouse from the 70s. Thames Court, the office building to the right of the hithe, was complex to negotiate and build because of its history.

Absolutely fascinating…thank you for this…made my Sunday morning.

Very interesting as usual!

A very interesting piece. Thank you.

Wonderful article as always. I loved seeing the cobblestones in the old photos. You have put in a lot of effort for which many thanks

I was born in 1946 My parents lived in Park Buildings Paradise Street Rotherhithe 2 minute walk from the river opposite the then river police I had 3 uncles worked at Butlers Wharf My dad had a little pony and cart and worked for Eliza Wells at Rotherhithe then went on to drive for BRS. He used to take me out in the cab and buy me El dorado ice cream Once again thankyou for your wonderful articles

Another fascinating blog, thank you so much. I have just written a walk in which Queenhithe is included as one of my stops and so this was especially useful reading for me. It is particular wonderful to see the old photos with the lighter boats in the harbour. Thank you so much.

Great stuff – thank you.

Fascinating as always!

Tis strange this stale Cheat should still prevail.”

Love this old language.

Really interesting as always, thanks.

Lovely article, thank you. Queen Matilda, or the Empress Maud as she was known, is also the origin of the area known as Bow (as I’m sure you already know). She ‘built’ a bridge over the river Lea, in that area, that was arched like a bow at a place where, either, she liked to bathe or where she fell in – or both! Stories differ. A fascinating woman and the originator of the ‘Anarchy’ against Stephen, a history worth reading! Thank you again for your fascinating article and reminding me of this interesting period in history.

Frank Cecil Monk was my grandfather and was a Wharfinger at Hayes Wharf I think. He died in 1922 after catching a bad cold while meeting an incoming ship. It turned into pneumonia

So interesting, thank you.

On a market stall a few years ago I was fortunate to pick up (for £4!) copy no.77 of the limited edition of The Book of Queenhithe 1979 by Gilbert Torry. My particular interest in Queenhithe was because in doing family history research I discovered that in the early 1700s some of my ancestors were living there and that they were buried ‘in the middle isle (sic) of St. Michael’s Church’. I wonder what happened to their grave when the church was demolished.

I very much enjoy reading your excellent posts – thank you for sharing the images and research.

I wonder if you could tell me which volume of Wonderful London the atmospheric image of QH came from?

Thanks for another fascinating article – always a pleasure to see your email arrive in my inbox.

Another fascinating post. Thank you very much for all of them.

I think King John gave the revenues from Queenhithe to his mother, Eleanor of Aquitaine c.1200.

Great piece of research – very enjoyable to read, as usual.