If you visit Bankside today, by far the main attraction is the reconstruction of Shakespeare’s Globe Theatre, however I would argue that there is a far more important historical building right next door to the Globe.

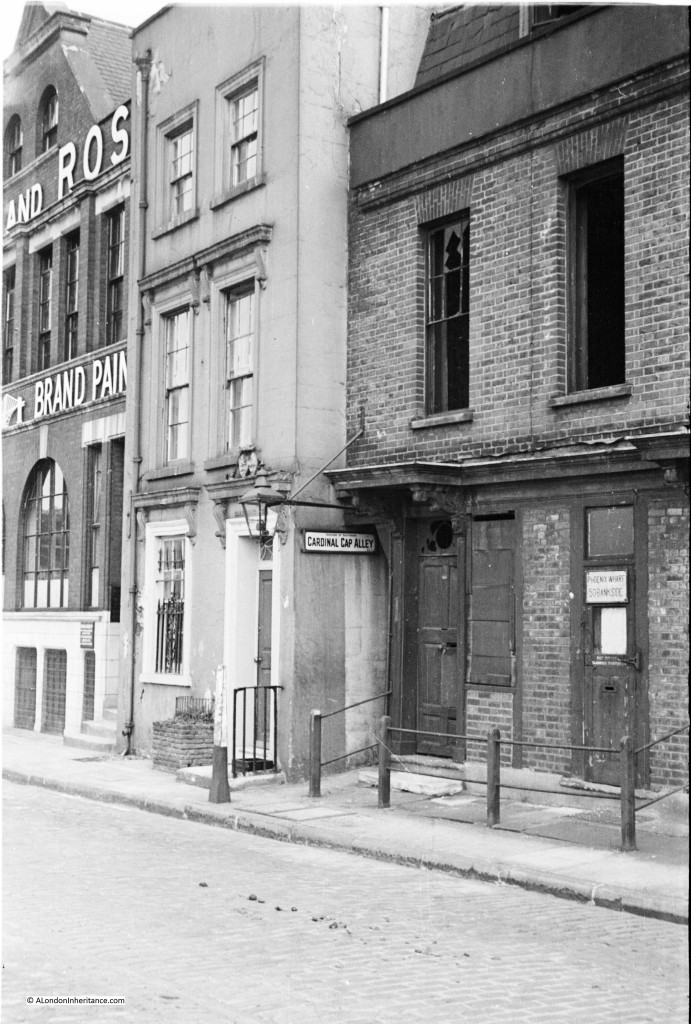

The following photo was taken by my father in 1947 and shows Cardinal Cap Alley. The building on the left of the alley is No. 49 Bankside, a building that exists to this day and has somehow managed to survive the considerable rebuilding along Bankside, and whilst having a well documented history, No. 49 also pretends to be something which it is not.

In the above photo, No. 49 and Cardinal Cap Alley are between one of the many industrial buildings along Bankside (Craig & Rose, paint manufacture’s ) and a short terrace of houses that were damaged by bombing in the last war.

The following photo is my 2015 view of the same area and shows No. 49 and Cardinal Cap Alley are now in between the Globe and the rebuilt terrace of houses, which were also reduced from three down to two houses in the post war reconstruction.

Cardinal Cap Alley and No. 49 have a fascinating history that tell so much about how Bankside has changed, and also how the history of the site can be traced to what we see along Bankside today.

As a starter, the following is from the London County Council Survey of London, Volume XXII published in 1950:

“The name Cardinal’s Hat (or Cap), for a house on the site of the present No. 49 Bankside, and for the narrow alley which runs down beside it, dates from at least the time of Elizabeth and perhaps earlier. The suggestion that it was named in compliment to Cardinal Beaufort is attractive but untenable, for Beaufort died in 1447, and the original Cardinal’s Hat was not built till many years later.

The site was described in 1470 as “a void piece of ground”. It is possible that it was named after Cardinal Wolsey who was Bishop of Winchester from 1529-30, although no buildings are mentioned in a sale of the site from John Merston, fishmonger, to Thomas Tailloure, fishmonger in 1533. Stowe lists the Cardinal’s Hat as one of the Stewhouses but he may possibly have been mistaken, including it only because it was one of the more prominent inns on Bankside in his day.

It is shown in the Token Book for 1593 as in occupation of John Raven and as one of a group of houses which in the book for 1588 is described as “Mr. Broker’s Rentes”. Hugh Browker, later the owner of the Manor of Paris Garden, was in possession of ground there in 1579 and it seems likely that he was responsible for the formation of Cardinal’s Cap Alley if not for the building of the original house.

Thomas Mansfield was the tenant of the inn when Edward Alleyn dined there with the “vestrye men” of St. Saviour’s parish in December 1617.

A few years later John Taylor, the water poet makes reference to having supper with “the players” at the Cardinal’s Hat on Bankside. Milchisedeck Fritter, brewer, who tenanted the house from 1627 to 1674 issued a halfpenny token. He was assessed for seven hearths in the hearth tax rolls.

The freehold was sold by Thomas Browker to Thomas Hudson in 1667. The later died in 1688 leaving his “messuages on Bankside” to his sister Mary Greene, with reversion to his great nieces Mary and Sarah Bruce. It was at about this date that the older part of the present house was built. During the 18th century it was bought by the Sells family who both owned and occupied it until 1830. in 1841 Edward Sells of Grove Lane, Camberwell, bequeathed his freehold messauge and yard and stables, being No. 49 Bankside, then in the tenure of George Holditch, merchant, to his son, Vincent Sells. The house is now owned by Major Malcolm Munthe. It has previously been occupied by Anna Lee, the actress.”

Although today the main Bankside attraction is the adjacent Globe Theatre, what does draw the attention of visitors to Bankside is the old looking plaque on No.49 with ornate script stating that Sir Christopher Wren lived in the building during the construction of St. Paul’s Cathedral and that Catherine of Aragon took shelter in the building on her arrival in London. This can be seen to the left of the doorway to No. 49 in my 2015 photo.

But a close-up of the 1947 photo shows no evidence of the plaque to the left of the door and there is no mention of it in the 1950 Survey of London.

The origin of this plaque is documented in the really excellent book “The House by the Thames” by Gillian Tindall.

As the name suggests, the book is about the history of No. 49 Bankside, the occupiers of the house and the industries around Bankside. It is one of the most interesting and well researched accounts of a single house and its’ surroundings that I have read.

In the book, Tindall confirms that the plaque is a mid 20th Century invention. Malcolm Munthe, who purchased the house just after the end of the war, probably made the plaque himself and installed on the front of the house. There was a plaque on a house further up Bankside, claiming the occupancy of Wren, however this house was pulled down in 1906.

A close-up of Cardinal Cap Alley and the entrance to No. 49, showing the Wren plaque to the left of the door.

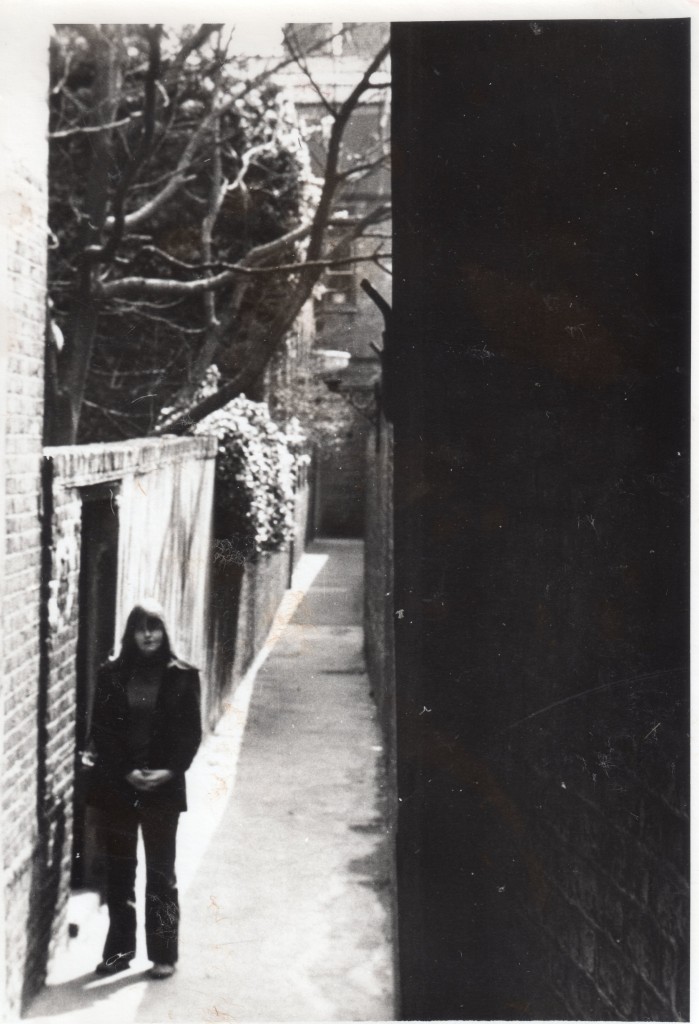

Also note that Cardinal Cap Alley is now gated. This use to be freely accessible and I took the following photo from inside the alley in the 1970s. Could not deal with the contrasting light very well, I was very young and this was with a Kodak Instamatic 126 camera – my very first.

I did not take a photo looking down into the alley, probably thinking at the time it was not as good a view as across the river, however it is these views which are so important as they show, what at the time, are the day to day background of the city which are so important to record.

I am very grateful to Geraldine Moyle who sent me the following photo taken in 1973 looking down into Cardinal Cap Alley:

The garden of No. 49 is on the left. Just an ordinary alley, but so typical of all the alleys that would have run back from the water front, between the houses that faced the river.

Tindall’s book runs through the whole history of No.49 and demonstrates how the history of a specific site over the past centuries has influenced the site to this day.

The occupiers of No. 49 and the adjacent buildings ran the ferry boats across the river, were lightermen and watermen and then moved into the coal trade. The Sell’s family who lived in the house for a number of generations, and who built a very successful coal trading business, finally merging with other coal trading companies to form the Charrington, Sells, Dale & Co. business which generally traded under the name of Charrington (a name that will be very familiar to anyone who can remember when there was still domestic coal distribution in the 1960s and 1970s).

How the history of Bankside has evolved over the centuries:

– the original occupations of many Bankside residents of ferrymen, lightermen and watermen. Working on the River Thames with the transportation of people and goods.

– as the transport of coal became important to London, the development of many coal trading businesses along Bankside, including that of the Sell’s family

– the local coal trading led to the development of coal gas and electricity generation plants at Bankside (the Phoenix Gas Works are shown on the 1875 Ordnance Survey map covering the west side of the current Bankside Power Station / Tate Modern.)

– the first electricity generating plant being replaced by the Bankside Power Station that we see today and is now Tate Modern.

To quote Tindall:

“And this is why at the end of the twentieth century, a huge and distinctive brick red building was there to make an iconic focus for the regeneration of a Bankside from which industrial identity had by then fled.

Thus do patches of London’s ground, which are nothing in themselves but gravel and clay and river mud, and the ground down dust of brick and stone and bones, wood and wormwood and things thrown away, acquire through ancient incidental reasons a kind of genetic programming that persists through time”

This last paragraph sums up my interest in the history of London far better than I could put into words.

I really do recommend “The House by the Thames” by Gillian Tindall.

Going back to 1912, Sir Walter Besant writing in his “London – South of the River” describes Bankside at the height of industrialisation:

“Bankside is closely lined with foundries, engineering shops, dealers in metals, coke, fire-brick, coal, rags, iron and iron girders. the great works of the City of London Electric Lighting Corporation, which lights the city, is also here. On the river-side is a high brick building containing the coal-hoisting machinery. All is automatic; the coal is lifted, conveyed to the furnaces, fed to the fires, and the ashes brought back with hardly any attention whatever, at an immense savings of labour.”

Standing in Bankside today, the area could not be more different.

Another view of No. 49 Bankside. The street in front of these buildings is the original Bankside. As can just be seen, this comes to an abrupt stop due to the land beyond being occupied by the Bankside Power Station complex. It is perhaps surprising that N0.49 and Cardinal Cap Alley have survived this long given the considerable redevelopment along this stretch of the river. It is ironic that perhaps the false plaque claiming Sir Christopher Wren’s occupancy may have contributed to the survival of the building during the last half of the 20th century.

My father also took a photo from Bankside across the river to St. Paul’s Cathedral. The larger ship traveling from left to right is the Firedog, owned by the Gas Light & Coke Company. Originally founded in 1812, the company had a fleet of ships to transport coal to the gas works it operated around London (this was before “natural” gas was discovered in the North Sea. Prior to this, gas was produced from coal). The Gas Light & Coke company absorbed many of the smaller companies across London before being nationalised in 1948 as a major part of North Thames Gas, which was then absorbed into British Gas.

The same view in 2015. The only building on the river front to have survived is the building on the far right. Note the building in the middle of the 1947 photo. This is the head office of LEP (the letters can just be seen on the roof), the company that operated the last working crane on the Thames in central London, see my earlier post here. It is really good to see that the height of the buildings between the river and St. Paul’s are no higher today than they were in 1947. A very positive result of the planning controls that protect the view of the cathedral.

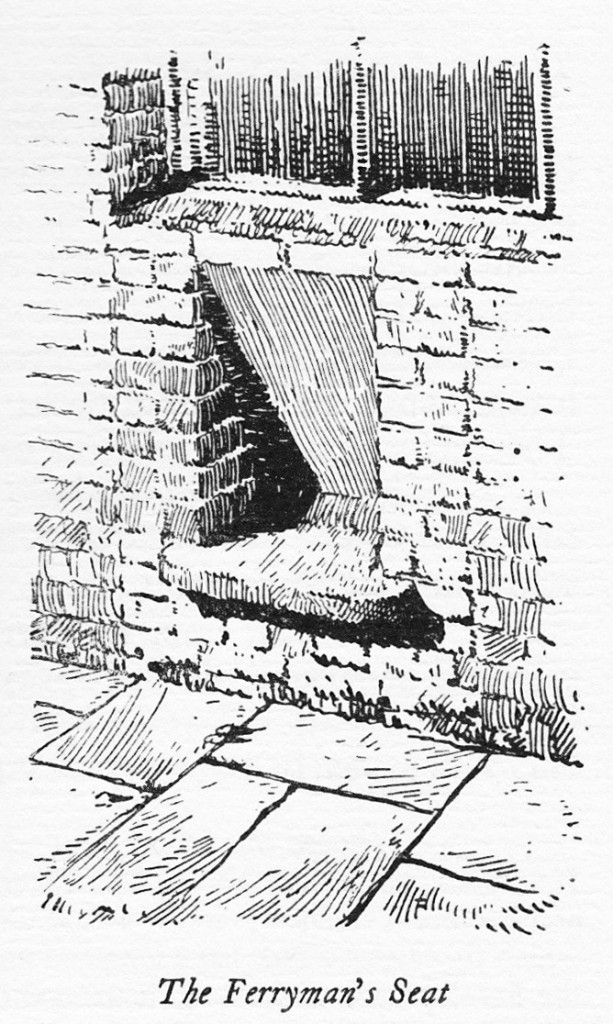

There is one final reminder of Bankside’s past. Walk past the Globe and on the side of a modern building with a Greek restaurant on the ground floor is the Ferryman’s Seat:

The plaque states;

“The Ferryman’s seat, located on previous buildings at this site was constructed for the convenience of Bankside watermen who operated ferrying services across the river. The seat’s age is unknown, but it is thought to have ancient origins.”

Although there is no firm evidence of the seat’s antiquity, the 1950 Survey of London for Bankside includes a drawing of the seat in the building on the site at the time and states that “Inserted in a modern building at the corner of Bear Gardens and Bankside is an old stone seat said to have been taken from an earlier building and to have been made for the convenience of watermen.”

Read Gillian Tindall’s book, then visit Bankside. Ignore the crowds around the Globe and reflect on Cardinal Cap Alley, No. 49 and the lives of countless Londoners who have lived and worked on Bankside over the centuries.

Very nice post, thank you. It is this type of detail that I enjoy most about London.

Regards, Baldwin

Baldwin, thanks for your feedback, much appreciated. This small site is so fascinating and tells such a story of how Bankside has evolved over the centuries, and it is the detail which I also find so interesting.

Thank you, a really fascinating article. I remember first seeing the house in the 70s and being amazed at the plaque. What a shame it’s not genuine. It could be referring to a previous house/structure that was there? Although ‘no building were mentioned’ in the 1533 sale, there could have been something there….. I’m hoping there was.

I have the book. I read an article years ago in The Standard which mentioned the author, the book and owners at that time. I had to buy it. Next time I’m in London I must visit my old haunts again.

That was a very informative post today. I especially liked your comment that the ‘false plaque’ regarding Sir Christopher Wren’s supposed residence may have helped this small area to survive attempts to rebuild the site. Perhaps a few more of those could save a little more of our town? Of course,the old Gas,Light and Coke company never went away, they became the G.L.C!!

Perhaps you are joking, but surely the Gas Light and Coke Company became part of the nationalised Gas Boards, and then the (re)privatised British Gas?

I will double check my text. From the information I have been able to find, the Gas Light and Coke Company became part of North Thames Gas (which was one of the regional Gas Boards), before they were all integrated into British Gas, which as you say was privatised. I will need to check, but I beleive that the regaional Gas Boards were at some point integrated into a single entity prior to privatisation. Not sure when this happened.

Great article and I agree the book is excellent! I have often visited and photographed the house and closed off alley but never knew about the ferrymans seat which I will definitely look out for when I am next in the area. I do think the old black and white photos of your fathers are amazing. Thanks for sharing them with your readers.

In Peter Burman’s guide book St. Paul’s Cathedral (Bell’s Cathedral Guides) O/P

It says that,

“In retirement he (Wren) lived on the Green at Hampton Court in the official residence of the Surveyor; though he retained a small house in central London, too, from which he could revisit St. Paul’s.”

It seems more likely that Wren lived in this house in central London whilst rebuilding St. Paul’s and 50+ City churches!

Hi Sara, from Gillian Tindall’s book, Wren did live for a while on Bankside, but in a house a bit further west, not No.49 with the plaque. I have found no mention of Wren living in No. 49 in any book prior to the 1950s and my father’s photo from 1947 does not include the plaque, which would indicate it is later addition as proposed by Gillian Tindall. Bankside does look an ideal location to live during the construction of St. Paul’s as there is a superb view across to the Cathedral.

When I was training to be a St Paul’s Guide at the end of 2011, I had to read a lot of books about the Cathedral, Wren and the rebuilding of the City one of which was ‘Building St Paul’s ‘ by James Campbell, published by Thames & Hudson. This book is still in print and tells the fascinating history of the 5th Cathedral on this site dedicated to St Paul In Chapter 6 is the following:

“In 1669 Wren was appointed Surveyor of the King’s Works and he was given a substantial house in the Palace of Whitehall, where he lived. This house overlooked Scotland Yard, the centre of operations for the whole of the King’s Works, which contained houses for the other officers and areas for storing materials.”

If Wren did live on Bankside perhaps it was before 1666? He certainly would have had a good view of The City.

I have the same book (bought in the bookshop at St. Paul’s), agree with you it is a fascinating history and Bankside does provide a good view of the City and I hope that planning regulations continue to limit the height of buildings between the river and Cathedral. Regarding books, I received last weekend the English Heritage book St Paul’s Cathedral Before Wren by John Schofield. A very detailed account of the site prior to the present cathedral. Must be really interesting being a St. Paul’s Guide.

Fascinating post! I’ve always been intrigued by these buildings. Surprised I’ve never noticed the Ferryman’s Seat, will have to look out for this next time I’m passing by. Will also look up Tindall’s book too. I think I remember there used to be a plaque in The Anchor pub (before it was renovated/extended) which said Shakespeare used to drink there!

Thanks – the Ferryman’s Seat is tucked away on the side of the building, not directly facing onto Bankside so not obvious. I do recommend Tindall’s book, a really fascinating account of how a small area of London developed.

Another wonderful, fascinating blog. I spend a couple of days a week working in an office immediately behind 49 Bankside and the cottages. I showed your fathers photos to colleagues in our office, and not one person was able to place it, until I showed them your contemporary photograph. Many thanks for teaching me something new and interesting about a place that I see hundreds of times a year. I too had not noticed the Ferryman’s Seat previously, but I wander over to take a look yesterday. Cheers

Hi David, thanks for the feedback, really appreciated. If you work in the area I highly recommend Gillian Tindall’s book, The House on the Thames. Really brings to life the long history of Bankside.

Like you, I found Gillian Tindall’s “The House By The Thames” quite simply wonderful, to the point that I also bought & enjoyed her history of Kentish Town, a place with which I had no associations at all: “The Fields Beneath” (1977). She’s a pioneer in writing the history of place, inspiringly so.

I’ve said before how much I value your blog. I just wish I could send you my photo from 1973 that shows the view down Cardinal Cap Alley, looking south ~ i.e. before the alley was fenced off. Please let me know if you’d like to see it.

Geraldine, thanks for your comments about the blog, very much appreciated. I would really like to see your Cardinal Cap Alley photo, I have not seen one looking south. You can e-mail to my address on the front page of the blog. If OK with you, I can add to the page on Cardinal Cap Alley and will off course credit to you.

really enjoyed this. very glad to have found your blog

Thanks Toby, appreciate the feedback.

I was on patrol along Bankside last night … an area I have know for some 20 years!

Always look for new things to see (& impart to my young charges who seem to just amble along without actually observing), I noticed first the name, unusual me thinks, I know who can use this a mate who is seeking to become a Black Knight of the road (London Cabbie for those unused to the colloquium).

However curiosity got me & via the power of ‘tinernet’ I am now apprised of a great history!

I was just in the process of updating and relaunching an old post I did on 49 Bankside when I stumbled into your blog (so to speak). Looks wonderful – and fabulous photos! You have a new follower and I will put a link to the above excellent article from mine, just in case anyone reads what I say… I’ve never seen the Ferryman’s Seat, either – will keep an eye open next time I’m down/round that way.

Off to london next month and after reading about Wren will visit 49 Bankside.

Interesting read. I spent a lot of time down on Bankside, sitting on the steps by Southwark Bridge. This would have been ’81 or ’82, long before some of the changes.

I live in Ireland now but I was back there a couple of years ago and it’s a bit different to what I remember, although I did get a nice breakfast in the Founders Arms.

Also my dad, who was a builder and decorator back then did some work on No.49. He used to tell my sister and I that the man who lived there, I think his name was Guy? slept in a coffin in the basement. I don’t know how true it is, but it was a good story.

‘ The London Nobody Knows’ a 1967 documentary with commentary by James Mason brought me here. Mason goes down Cardinal Cap alley in the film. Trying to find it googling on streetmap proved fruitless though. Maybe because it is now closed off? The film can still be found online though.

Nice, informative piece of writing about our great city. Thanks.

I have just watched the same for a second time, the first being many years ago.

Brought me to this site also!

One of my ancestors, Samuel Rush, who owned the Southwark vinegar distillery (which later became Potts) lived in this house. Wonderful to find your article as I am doing alot of ancestry research.

Interesting post and pics, thanks! The London Nobody Knows Film of the late ‘60s with James Mason includes a section on Cardinal Cap Alley and No 49.

In the novel Russian Roulette by James Mitchell (whose stories led to the popular 1970s TV series Callan) – there’s a short section which reads…

“…they walked along the riverside, stopped and stared at the cathedral, marvelled and walked on to where Callan showed her a narrow, slender house, dainty as a doll’s house, its seventeenth prettiness raddled by decay.

‘Oh what a shame’, she said. ‘It’s lovely. Who lived here?’

‘Sir Christopher Wren’, he said. ‘He could wake up every morning, look out of the window and see how his cathedral was doing.’

She looked from the house’s miniature elegance to the great church’s massive solemnity…”

James Mitchell’s book was first published in Great Britain in 1973. It’s likely he was writing about a contemporary London, and so this would coincide with the picture you took on your Kodak as a youngster.

Many thanks for very interesting blog.

Thank you for the wonderful post. I have been told the “Winchester Geese” used to work at no. 49. Is there any truth in that?

Thank you for this fascinating article. A detailed account of legal developments/changes affecting Cardinal Cap Alley can be read at bermondseyphotographs.blogspot.com/p/the-strange-tale-of-cardinal-cap-alley.

My family were the watermen a lightermen that lived in 42 Bankside, my gt gt grandfather James Bullock lived there and was involved with Reddin’s wharf and his son, my gt grandfather was born there. I also was a lighterman/waterman, my family’s records from the Company of Watermen and Lightermen go back to pre 1666.

I thank you for your interesting article.

I was informed by a tour guide that Cardinal Cap Alley is illegally cordoned off.

The tenants did not like hoards of tourists walking down the alley, making noise, so he put a gate/barrier there.

It is in fact (apparently) a public right of way.

No one can deny you entry.

I have attempted to send a photograph of Bankside twice but the address said ‘Unknown’ of a River procession of assorted tugs and boats along with a barge being rowed by 3 lightermen, dressed as they would have been 100 years earlier, from Westminster to Tower Bridge during the 1995 centenary celebration of the Bridge. The Royal Yacht was at the bridge along with a Norwegian cruise ship the ‘Viking Star’ the Bascules were raised when the barge reached the bridge then 2000 balloons were released, a River show followed by an amazing firework festival. Unlike the 125th birthday of the bridge, there were no tv camera’s and apparently no mention in the Tower Bridge Museum of the Festival.

Wonderful blog! I too read Tyndall’s book and was totally enchanted. I was recently in London just for a day and a half and had planned to go see the house. But alas! Didn’t make it (thwarted by the heat and tiredness-came down with the dreaded Covid). So disappointed, hopefully I will get another chance!

I worked in St Christopher House in Southwark Street from 1977 to 1978. At lunchtime I would love to explore the Bankside area. I particularly recall drinking in the Anchor and having an occasional lunch with a lady friend. I recall there being some kind of beer garden beside the Anchor as well as a platform across the riverside path. All the other buildings were derelict warehouses and I suppose the remains of the brewery behind the pub. It was intensely atmospheric – like stepping back into Dickens’ London. I knew it at the moment between the end of industry and the start of redevelopment. Any photos?