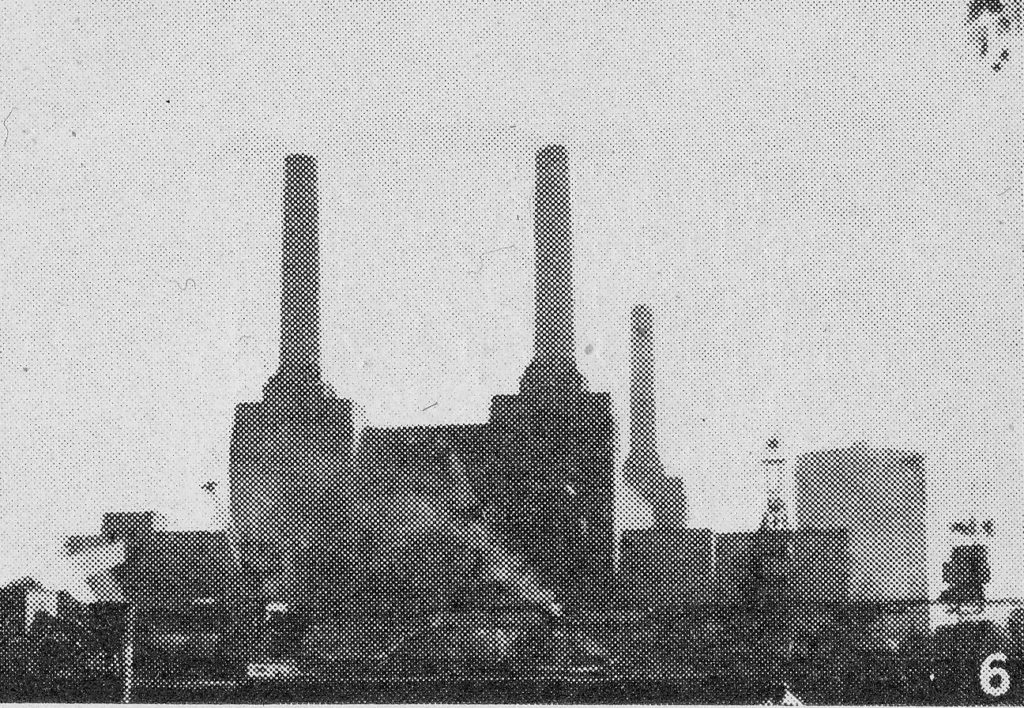

In photographing London, I try to get to places before they change, which is not an easy task given the rate of change in London. One area undergoing significant change is Nine Elms, and indeed the whole arc to the south of the river between Battersea Power Station and Vauxhall. This must be one of the largest construction sites in the country, with demolition of acres of industrial space, to make way for a forest of new apartment towers.

The most well known new occupant of this area is the United States Embassy, however the majority of the area is still a construction site and recent demolition has cleared a new area for development.

I am occasionally on the train between Clapham Junction and Waterloo and the train provides a perfect view of Nine Elms. I have been planning to take a walk around the area, but the view a couple of weeks ago prompted me to walk Nine Elms sooner rather than later.

The view from the train was the usual acres of cleared space ready for new construction, along with a range of new apartment towers in various stages of completion, however what caught my eye was at the edge of one of the recent blocks of demolition, a row of what looked to be early 19th century houses were visible. An unexpected sight given that this area was previously occupied by light industry, numerous courier companies, car repair businesses, markets etc.

Last Sunday I had a couple of hours spare in the morning. so I headed to Vauxhall to take a quick walk around Nine Elms, to find the houses I could see from the train. I also found hundreds of people making their way from Vauxhall to Nine Elms wrapped up against the cold of a January morning.

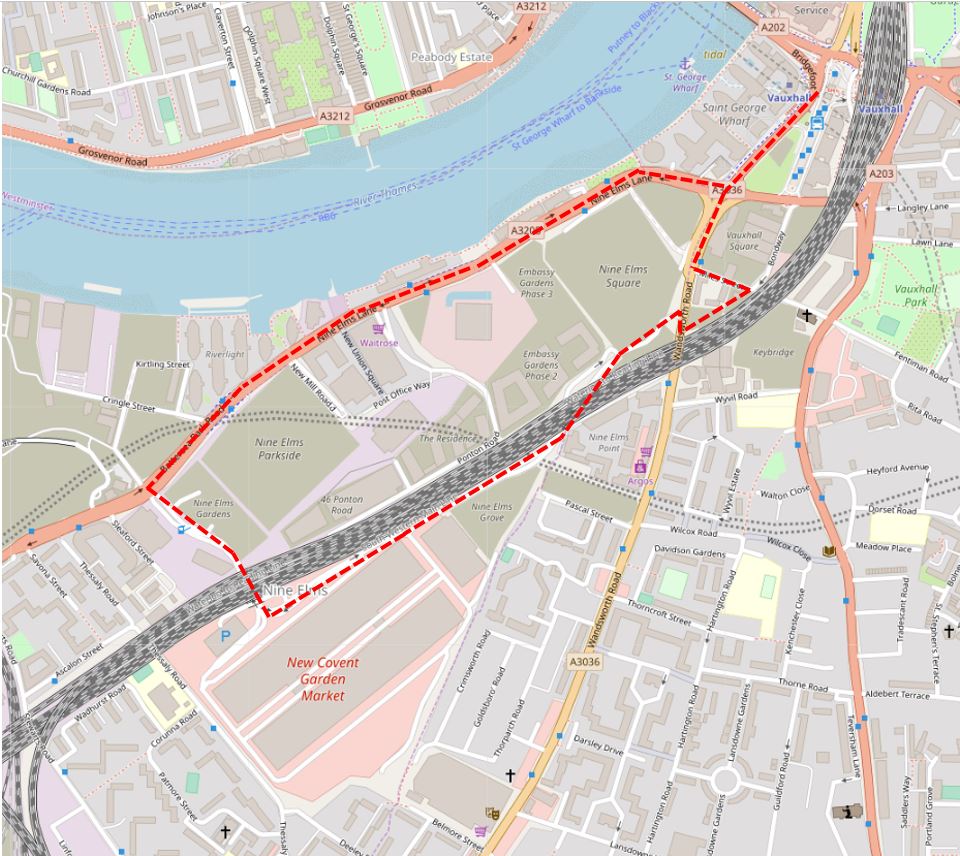

Walking across Vauxhall Bridge, I headed along Wandsworth Road to find the houses I had seen from the train. I have marked my full route around Nine Elms on the following map.

Maps © OpenStreetMap contributors.

I have also added the times each photograph was taken to record a January Sunday morning in Nine Elms.

09:43

I found the houses I was looking for a short distance along the Wandswoth Road, just before the junction with Miles Street. A terrace of six houses with three taller on the left and three shorter on the right.

Of the six houses, a couple look as if they have been cleaned whilst the house on the far right looks rather strange when compared with the other five, one window per storey rather than two. They currently appear to be providing office space for activities associated with the redevelopment of the area.

Although Nine Elms may be considered a rather unattractive area, it has a fascinating history and has been a key location in the development of the railway system to the south of London.

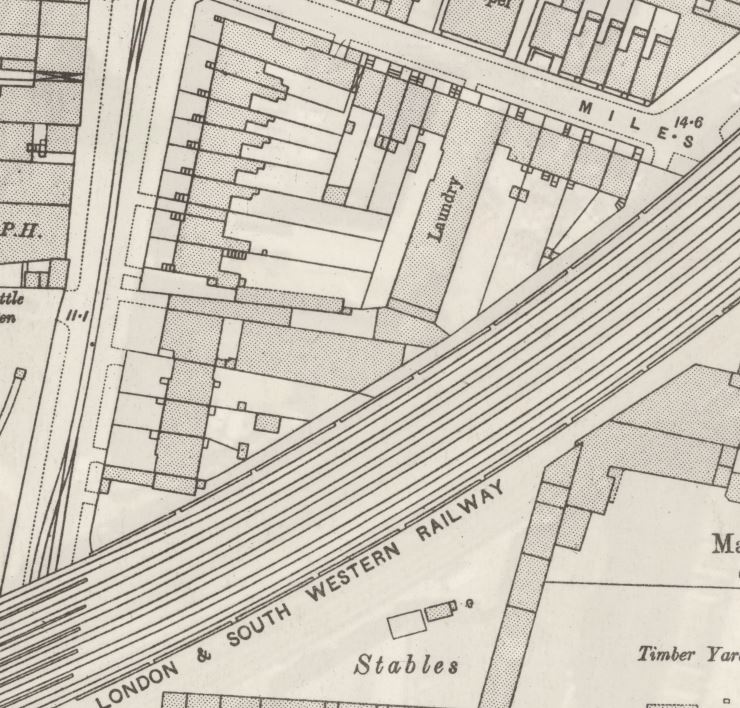

The 1895 Ordnance Survey map provides a good overview of the area following the first wave of development, and also locates the houses that still stand on the Wandsworth Road.

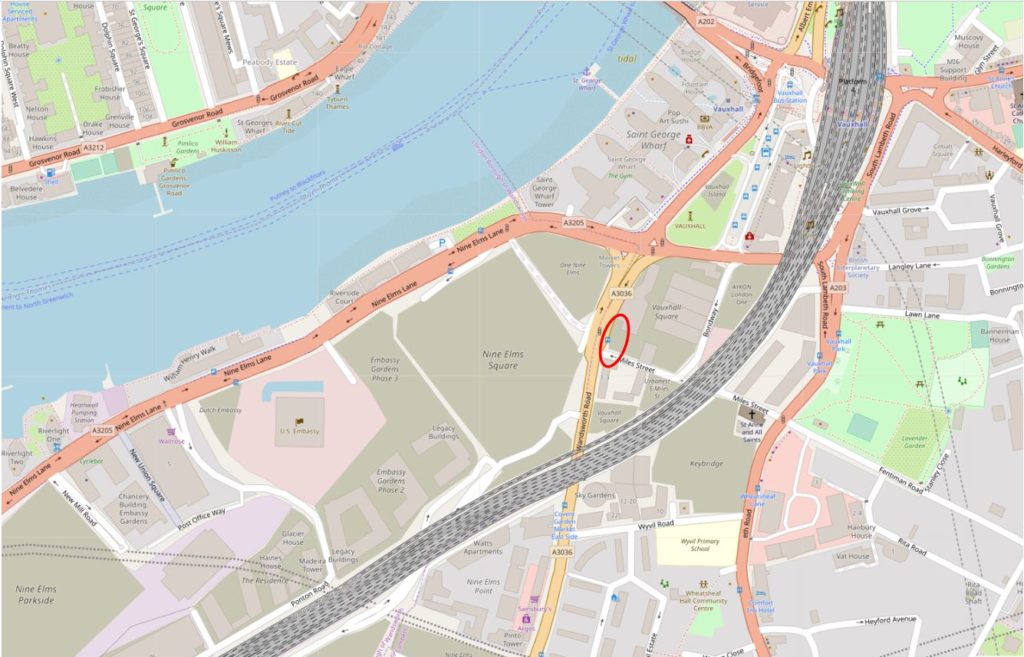

The following extract from the map shows the railway running into Waterloo Station towards the top right of the map. The area between the railway viaduct into Waterloo and the river has a considerable amount of railway infrastructure, including the Nine Elms Depot, however there are also pockets of housing with an oval shaped area between Wandsworth Road and the viaduct and it is here that we can find the six houses.

Credit: ‘Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland’

I have circled the six houses on the map, at the junction of Miles Street and Wandsworth Road. They are almost the only survivors from the nineteenth century, and it is surprising that these houses have lasted through successive waves of redevelopment.

The following map shows roughly the same area today as the 1895 map, again I have marked the location of the six houses.

There is so much history in this area. In the first decades of the 19th century, various schemes were looked at to try and speed up the transport of goods and people arriving by sea into London, as from the Atlantic, the route along the south coast then along the Thames added a number of days and were dependent on weather and tide. One scheme considered the construction of a canal from Portsmouth to London, but in 1831 initial plans were made for a railway from Southampton to London, with the London terminus at Nine Elms.

Construction of the railway from Nine Elms to Southampton started with the route to Woking Common in 1838. In 1846, a train pulled by an engine named “The Elk” ran from Southampton to Nine Elms in 93 minutes. By comparison, an on-time journey today takes around 80 minutes, so not a significant difference (although there is no mention of the number of intermediate stops for “The Elk”).

Nine Elms closed as a passenger station ten years later when the viaduct into Waterloo was built and the London terminus of the railway moved to the first Waterloo Station. Nine Elms then provided space for a Locomotive Works, which closed in 1909 when the works moved to Eastleigh in Hampshire. Nine Elms also provided space for a large Goods Yard and this continued in operation until 1968.

This photo from 1938 shows the scale of the railway sheds and goods yard at Nine Elms.

This post is already too long, so I will leave the history of the railways in Nine Elms for another time, and continue walking.

09:44

There was a continuous stream of people walking along Wandsworth Road, and just to the left of the six houses, one of the illegal betting scams normally seen on Westminster Bridge was in action, looking to take money from those streaming past – and probably those less able to manage the inevitable loss.

This is obviously a problem in the area as there are signs up along the street advising people not to participate in these activities.

I walked past the houses and tuned into Miles Street and walked down to take a look at the rear of the buildings.

09:45

This explained why one of the end houses looked so different. The view from the back shows that the end house appears to be a new build. The other houses in the terrace look original from the rear.

Hoardings lined the edge of Miles Street, hiding the areas of demolition that had opened up the view of these houses from the railway. There were a couple of gates where it was possible to peer through.

09:46

The above photo is looking through a gate onto the open space between the six houses (on the immediate left) and the railway viaduct (out of view on the right). Vauxhall is in the distance and only part of the space is visible, there is more to the right. The demolition of the buildings in this area opened up the view of the six houses from the railway.

09:47

The above view is from the point where Miles Street meets the railway viaduct. The large open space is behind the hoardings on the right and the six houses can be seen in the distance.

09:47

Just before the point where Miles Street passes under the viaduct there is a street running towards Vauxhall. The following photo shows this street and also highlights one of the problems of walking around this area, so many streets have been closed off for construction. This is happening so rapidly that online maps such as Google and OpenStreetmap are not up to date with changes in the area.

The above view is looking along the viaduct towards Vauxhall and Waterloo. Looking in the opposite direction and there are new buildings and a walkway alongside the viaduct – this was the direction that I decided to follow.

09:47

A newly surfaced walkway runs alongside the viaduct and what appears to be a new student accommodation building on the right. Further along this walkway is a rather strange survivor from the 19th century.

09:49

At the end of the student accommodation building is this strange wall.

On the opposite side of the wall is a small electricity substation, so I am not sure if this is the reason why the wall has survived, I can see no other reason. The wall is not at right angles to the viaduct, it is slightly angled. The following is a detailed extract from the 1895 Ordnance Survey map. Miles Street is at the top and the route of the walkway is from Miles Street down, along the edge of the viaduct. Halfway along there is a large building, at an angle to the viaduct. I suspect that the wall is the remains of the uppermost wall of this building, the section where it is joined on to the smaller building at the end of the Laundry.

No idea why the wall has been retained, however I really do hope that it remains exactly as it is, a shadow of the many buildings that once occupied this area over a century ago.

09:49

Goal on the viaduct:

The end of the walkway joins Wandsworth Road, which I crossed over to walk along Parry Street. This is a narrow street that heads underneath the viaduct.

09:54

A look back down Parry Street at the continuous stream of people:

There are a couple of tunnels underneath the viaduct. The majority of people were taking the direct road route, I spotted a narrow entrance and went to take a look at what was intended to be the pedestrian route under the viaduct.

09:55

I love railway viaducts. They are brilliant examples of Victorian construction, and whilst train passengers pass above, there is a different world of passages and arches underneath.

09:56

Reaching the other side of the viaduct and there are a number of businesses operating in the arches. Espirit Decor:

09:56

And Sophie Hanna Flowers (a logical location given the flower market which I will soon find).

09:57

Directly opposite is the Nine Elms construction site for the Northern Line extension from Kennington to Battersea,

09:57

The viaduct now takes on a different appearance with infrastructure to service the tracks above and parking / workshop space for the considerable number of vans that wait here ready for their early weekday morning activity.

10:00

I had to wait for a gap in the stream of people walking along the road to take the following photo.

The photo does not really convey the view. I am standing surrounded by vans, a stream of people, wrapped up against the January cold and carrying bags, pulling shopping trolleys and wheeled suitcases walk below the railway tracks. Around them tall apartment blocks grow, each with a design that appears completely uncoordinated with any other, as if each had been designed in isolation and dropped from above onto Nine Elms.

This being a Sunday, the railway is relatively quiet. In the week a stream of trains would be taking commuters from the suburbs of London, the villages of Surrey, Hampshire and beyond into the city.

On the other site of the railway, huge signs advertise luxury apartments and penthouses.

10:01

Turning round and there is a large car park full of vans – this is New Covent Garden Fruit and Veg Market.

Just past the first market buildings was the reason for so many people walking along these streets on a Sunday morning as a large Sunday Market and Car Boot Sale operates here from eight in the morning to two in the afternoon.

10:03

This is not a market for arts and crafts, this is market for the basics in life. I did not have time to explore the market apart from a quick walk along a couple of aisles where there are clothes, bags and cases of every description, tools, mobile phones and tablets.

It would have been good to take photos in the market, but the last thing the people who have come shopping here on a cold Sunday in January want is some bloke taking photos.

The market appears to be known as a source for second hand tools. On my walk back to Vauxhall, a man with an east European accent asked where the tool market was. He had just arrived in the country looking for work and needed to find some cheap tools to get started. How many times has that happened in London over the centuries.

The market is very busy, the photo below shows the number of people walking to and from the market.

10:07

Continuing on, I walked through the man entrance to New Covent Garden Market.

10:10

Covent Garden Market had outgrown its original location by the early 1960s. Lack of space for expansion and congestion on the surrounding roads required a new location to be found. The Nine Elms site was identified in 1961 and construction of New Covent Garden started in 1971. The Fruit & Veg and Flower Markets moved from Covent Garden to Nine Elms in November 1974 to sites to the south and north of the railway viaduct.

The southern market has been demolished and relocated (which I will find soon), but the main fruit and veg market continues in the original 1974 location and many of the buildings have recently been rebuilt and refurbished, with further construction ongoing.

The market has a dedicated road tunnel under the railway viaduct allowing access to and from Battersea Park Road, so this is the route I took. Passing under the railway and the cranes surrounding Battersea Power Station come into view, further emphasising the sheer scale of the construction projects between Vauxhall, Nine Elms and Battersea.

10:15

It is along this road, just under the railway viaduct, that the new Flower Market has been located.

10:17

The entrance to the Flower Market:

The Flower Market was opened in April 2017 having moved from a location further down towards Vauxhall. That original site has now been demolished and cleared ready for new construction.

10:20

The new – New Covent Garden Flower Market in Battersea Park Road:

Completing a circular route, my plan was now to walk back along Battersea Park Road and Nine Elms Lane to where I started in Vauxhall. It is along here that some of the original apartment blocks from this recent phase of development can be found.

10:32

When redevelopment started, it was on the bank of the river, and over the last few years has continued back inland. Between Nine Elms Lane and the River Thames are five blocks of identical design/

On the opposite side of Nine Elms Lane, large areas of land have been cleared. The roads are ready and utility services laid underneath the roads ready to service the buildings that will spring up on either side.

10:36

10:38

Opposite is Cringle Street which leads to the large construction site surrounding Battersea Power Station:

Further along Nine Elms Lane there are a number of completed buildings.

10:40

A very quiet January Sunday morning:

Walking further along Nine Elms Lane and I found probably the most publicised building in the Nine Elms redevelopment.

10:48

This is the new United States Embassy:

It is January, it is a grey day, it is a Sunday morning so there are not many people around, the building is surrounded by construction sites, however comparing the new location to the original location in Grosvenor Square – it is very different.

I am sure it will be a much improved environment when the rest of the redevelopment of Nine Elms is complete. The hoardings around the site between road and Embassy are for the residential blocks that will be built here – the Embassy Gardens development. Based on the photos of potential residents on the hoardings around the building site, I doubt I fall within their age demographic.

10:50

Further down Nine Elms Lane:

10:55

Continuing along Nine Elms Lane and there is another large space cleared and ready for new construction. This was where the original flower market was located.

And if I have calculated the location correctly, it was also somewhere here that the original London terminus of the Southern Railway was located.

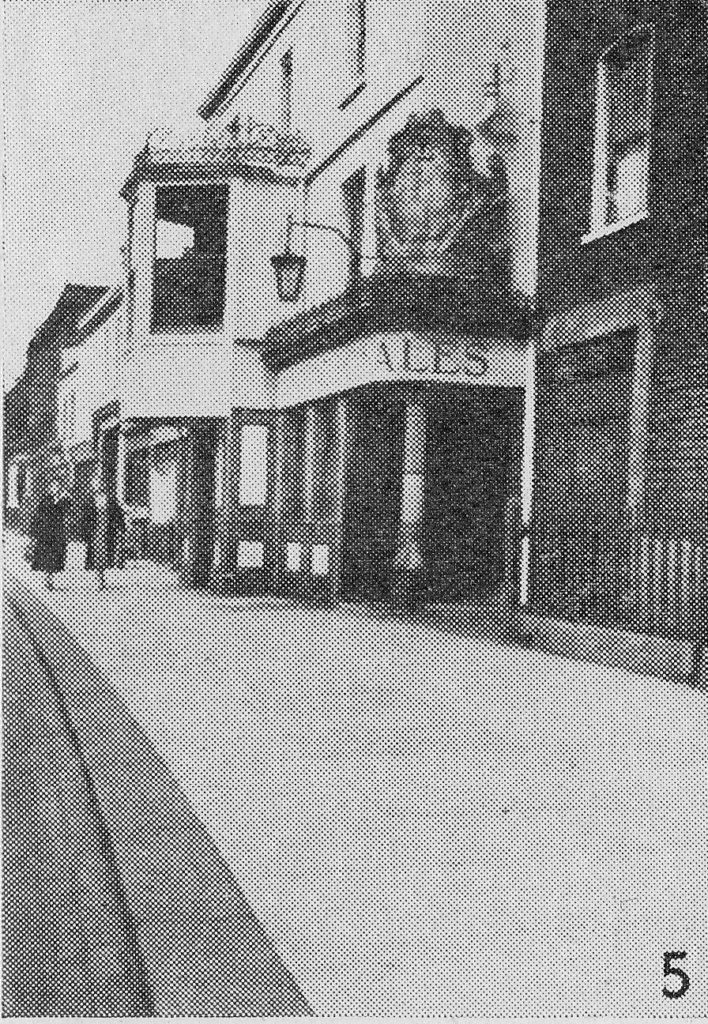

This was the street entrance of the terminal building in 1942. The building suffered bomb damage during the war and was demolished in the 1960s ready for the construction of the New Covent Garden Flower Market in 1974.

Image credit: London Metropolitan Archives, City of London: catalogue ref: SC_PHL_02_0629_F898

10:56

Mural by Wyvil Primary School – the mural informs that London is home to 914,000 children between the ages of four and eleven.

I now reached the junction of Nine Elms Lane and Wandsworth Road.

10:57

From here I could look down Wandsworth Road again to see the houses that were the reason for spending Sunday morning in Nine Elms.

It is a wonder that they have survived so long, given the closure of the railway station, workshops and good yards which were the catalyst for development of the area. The houses are probably of the same age as the original Nine Elms station.

The houses and the strange length of wall in the walkway alongside the viaduct are the only survivors from the 1895 map that I found, apart from the railway viaduct.

No idea what will happen to the houses. I hope they survive the latest phase of development and having seen the railway come and go, the Flower Market almost opposite built and demolished, they will now be surrounded by the towers that are springing up all around them.

11:10

At the junction of Nine Elms Lane, Wandsworth Road and Parry Street, the bright lights of Barbados shine on those still streaming from Vauxhall Station to the Sunday Market.

And as one final comparison photo, the old Brunswick Club building with the residential blocks behind in the above photo and the Nine Elms Cold Store in the photo below.

Image credit: London Metropolitan Archives, City of London: catalogue ref: SC_PHL_01_258_71_7183

Nine Elms is probably not high up on the list of walks in London, however I found it fascinating. The sheer scale of the redevelopment work, with the extension down to Battersea Power Station, is remarkable. Not just above the surface, but also below ground with the Northern Line extension. The Sunday Market also serves those who need somewhere to buy cheap goods and for those seeking to start a life in London.

Nine Elms has been through two development phases. Originally as the first Southern Railway terminus in London, then with the associated locomotive works and goods yard, then as the site for Covent Garden’s relocated fruit, veg and flower markets with other light industrial business. Now a third phase as Nine Elms transitions to a mainly residential area, however it is good to see that the market will stay here.

There is still much to explore in Nine Elms, and when I return I will check to see if the six houses have survived along with the strange wall alongside the viaduct.