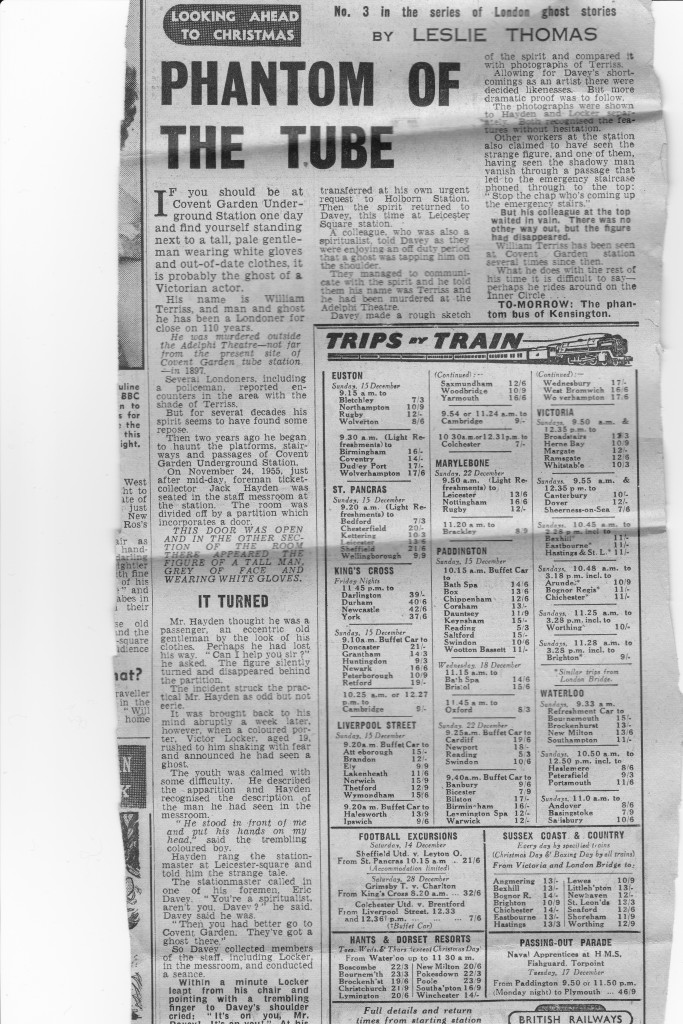

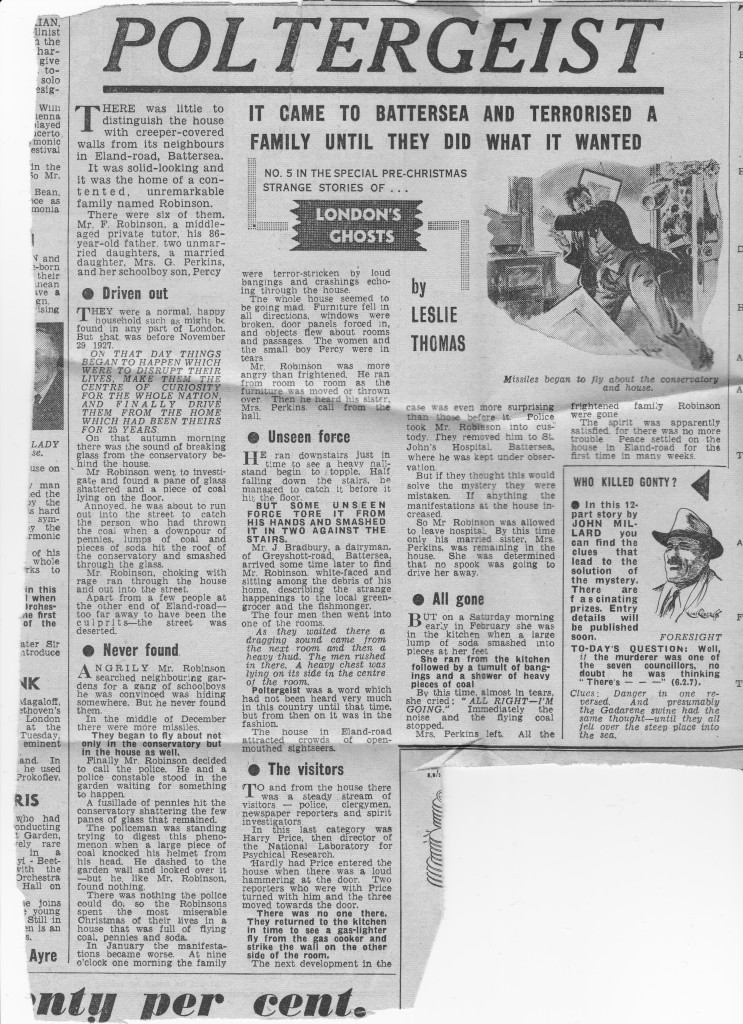

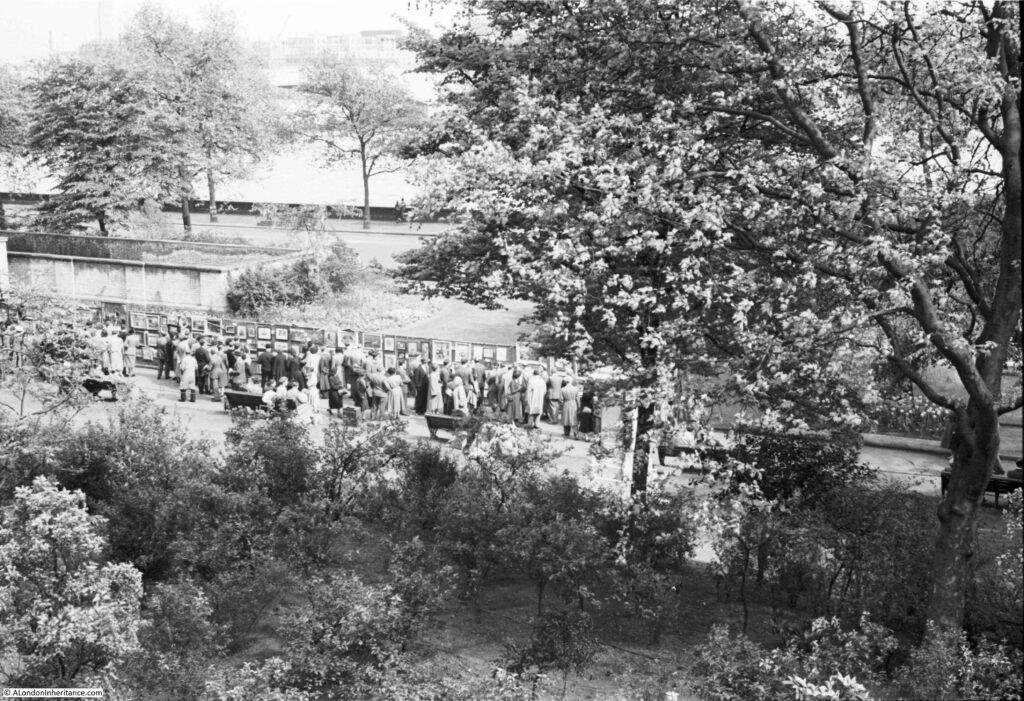

The Victoria Embankment Gardens has often been the location for an open air art exhibition, and a couple of the photos in my father’s collection show the 1952 exhibition:

This could have been a difficult photo to locate, however the feature in the background made it easy to find the exact place. This is the same scene on a very sunny June day in 2021:

The first exhibition appears to have been in 1948, as an article in the Sphere on the 23rd May 1953 describes that year’s exhibition as the sixth annual open air exhibition of contemporary art. The article also states that the exhibitions were sponsored by the London County Council, and that “On all days except the final day the pictures are for sale”, which seems rather strange, not also to sell them on the final day of the exhibition.

Exhibitions also seem to have been during part of the month of May, which would explain the coats worn by those in the photo, although that could really be any summer’s day given typical British weather.

The little girl in the photo looks to be around five or six. She would now be around 75 and the only one from the photo still alive.

The Illustrated London News on the 12th May 1962 describes that year’s exhibition as opening on the 30th April and running to the 12th May, with 700 paintings on display from both amateur and professional artists.

There is some British Pathe film of the 1949 exhibition which can be seen here, where “Our Roving Camera Reports”.

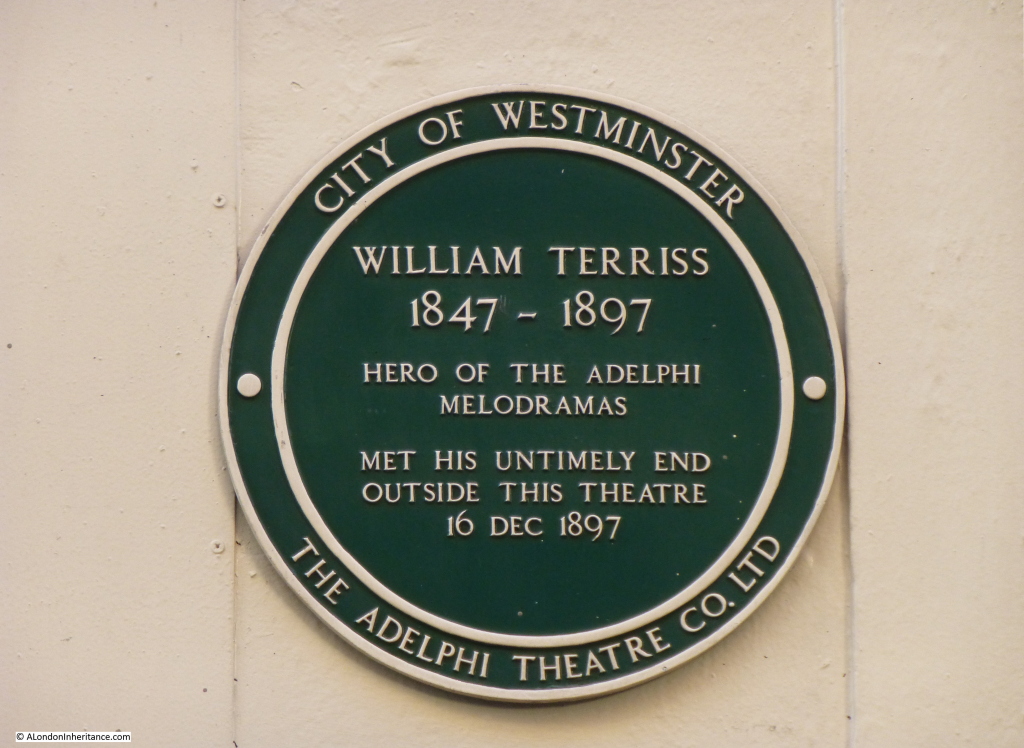

The monument behind the exhibition which enabled the location to be found, is to Henry Fawcett, the rather remarkable blind MP who championed the cause of women’s suffrage. His interests in the cause led him to meet Elizabeth Garrett who rejected his proposal of marriage in order to concentrate on becoming a doctor. He went on to marry Elizabeth’s younger sister, Millicent Garrett.

A statue of Millicent Garret Fawcett was unveiled in Parliament Square in 2018 with the words from one of her speeches “Courage calls to courage everywhere”.

The wall behind the monument is part of one of the air vents to the cut and cover underground Circle and District lines, a short distance below the surface.

The monument to Henry Fawcett:

A wider view of Embankment Gardens, with the monument on the left.

The gardens are looking very green with plenty of plants and trees, which would cause a problem trying to recreate the following photo of the art exhibition:

My father took the above picture from the Adelphi Terrace, overlooking the gardens. The art exhibition is running along the pathway through the gardens, and shows how far to the right the exhibition ran, as the edge of the Fawcett monument can just be seen on the very left edge of the photo. The Thames and Waterloo Bridge can be seen in the background.

Adelphi Terrace, from where the above photo was taken is shown in the following photo:

I walked up and down the terrace looking over the wall to the gardens below, trying to recreate my father’s photo, however the trees and bushes have grown considerably since 1952, and the best I could get was the following photo:

There is a small bit of wall visible in the gardens in the centre of the photo. This is not the monument or wall in the 1952 photo, rather a nearby fish pond, a short distance from where the art exhibition was held, and the nearest I could get to recreating the photo.

The Adelphi Terrace is in front of the Adelphi building, and raises the street around the Adelphi up above Savoy Place which runs at ground level between the Adelphi building and Embankment Gardens.

The following photo was taken from Savoy Place looking up at the terrace and the rather magnificent Adelphi building, and shows the height of the terrace:

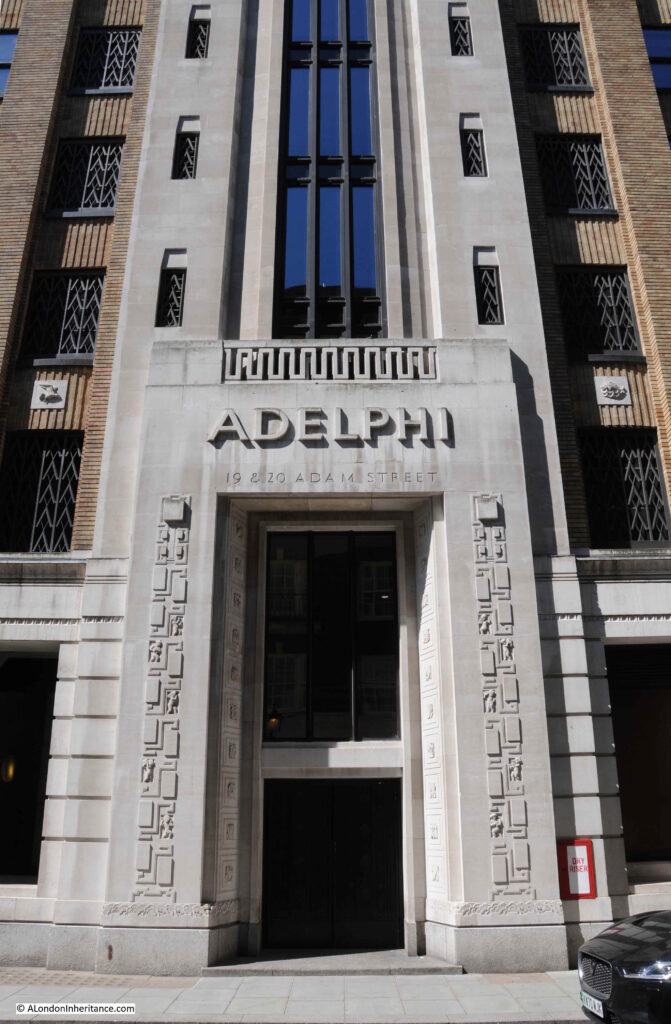

The main entrance to the Adelphi building is on John Adam Street, and the building consists of two outer wings which extend over the terrace as shown in the above photo, with the core of the building between and behind the two wings, up to John Adam Street.

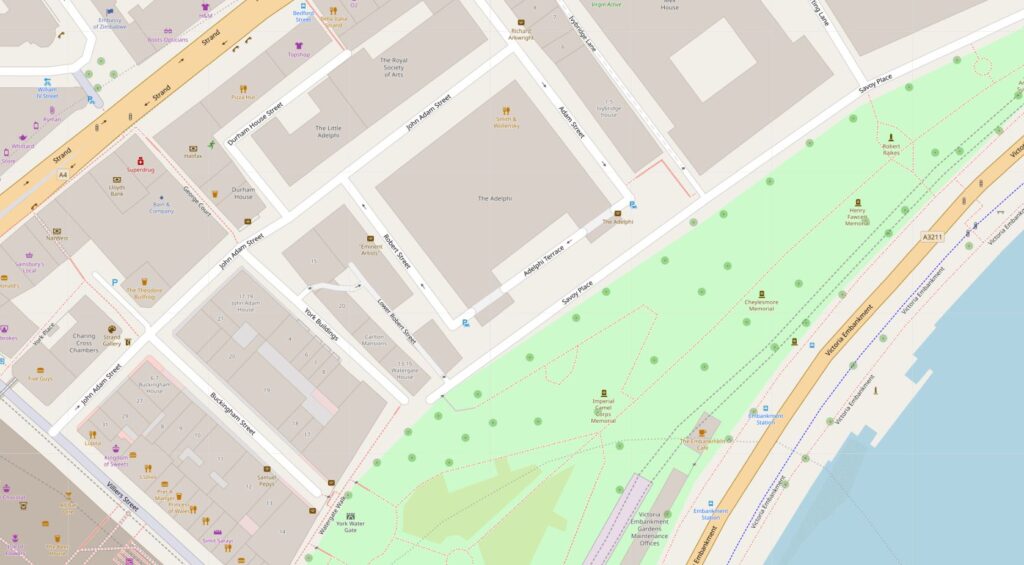

The Adelphi building is in the centre of the following map, which also shows the Victoria Embankment Gardens and the Henry Fawcett memorial to the right of the gardens (Map © OpenStreetMap contributors).

I thought I had a photo of the Adelphi from across the river, but I cannot find it. I did find a photo I took a few years ago which shows the three wings of the Adelphi as the building on the left of the photo.

From this distance the building does not look that impressive. It is only when you walk around the building that its unique decorative features can be seen.

The Adelphi was built between 1936 and 1938, by architect Stanley Hamp of the partnership Colcutt and Hamp.

Of standard steel frame and reinforced concrete construction, what makes the building rather special is the large amount of architectural decoration and design that follow the art deco approach.

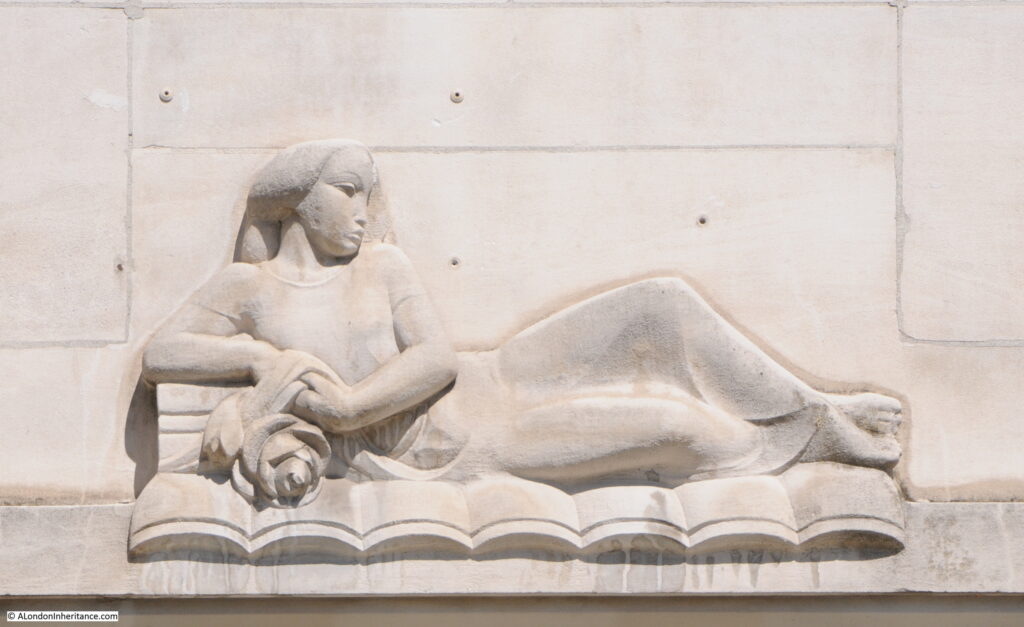

In the photo of the building from Savoy Place, two large allegorical relief figures can be seen on the two wings that extend over the terrace. There are four of these (the other two are on the other corners of the wings). These represent Dawn, Contemplation, Inspiration and Night, with Contemplation and Night being seen in the above photo.

The following photo shows a detailed view of “Night” by the sculptor Donald Gilbert.

The following photo shows “Dawn” by Bainbridge Copnall, with architectural decoration extending above the sculpture to fill in part of the curved corner of one of the wings.

There is detail across the building. The following photo shows a side entrance on Robert Street. Note also that where the building faces towards the river, Portland stone is used, with brick used for the other facades, but retaining Portland stone for the ground floor and architectural detailing.

The sides of the building have small decorative panels between the brick pillars:

And carved coats of arms of UK cities between the ground and first floors. Three of these can be seen in the above photo, and in close up, the arms of Sheffield, Derby and Birmingham can be seen below:

Another view of Adelphi Terrace, which was constructed in part due to the 1930s expectation of the rise of the car as a means transport within the city, as well as replicating the original terrace:

Construction of the Adelphi in the 1930s required the demolition of an historic estate.

The original Adelphi estate was the work of Robert Adams and his three brothers, John, James and William. The name Adelphi comes from the Greek word adelphós, meaning brothers.

In the mid 18th century, the area now occupied by the Adelphi had been a rather run down area called Durham Yard, which had been the location of Durham House. At the time, the Embankment Gardens had not been built, so the space now occupied by the Adelphi was then facing on to the foreshore to the Thames. The damp conditions and flooding at high tide meant that this was not a good area to build the type of quality houses intended by Adams.

The plan developed, mainly by Robert Adams, was to build the houses and streets on a series of arches, which increased in height as the land descended from the Strand down to the river.

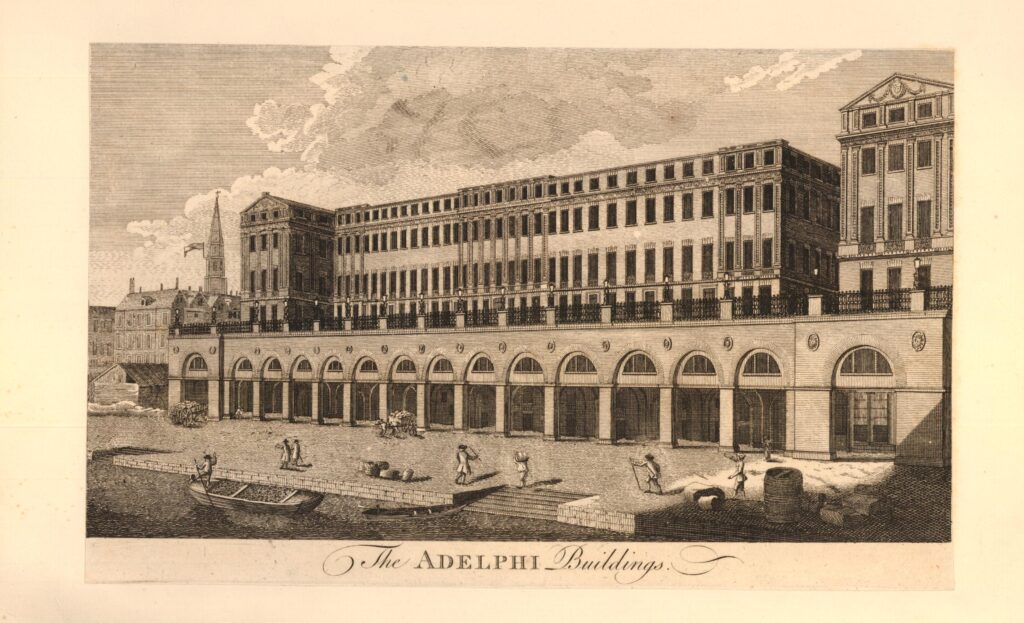

This was how the terrace came into being as the end of the estate overlooking what was then the edge of the River Thames. The following print from 1795 shows the terrace as it appeared soon after construction (© The Trustees of the British Museum):

However the Adelphi Terrace in the above print is not in the same position as the Adelphi Terrace we can walk along today. In the above print, the block of buildings on the right were demolished to make way for the Adelphi building (not the building at the far end as we shall see).

In preparation for the construction of the Adelphi building, the whole of the block of houses that occupied the area, included the arches and space underneath the houses, was demolished all the way back to John Adam Street. As part of the build of the Adelphi, construction was pushed forward up to Savoy Place, so the terrace is now forward of the terrace in the above print.

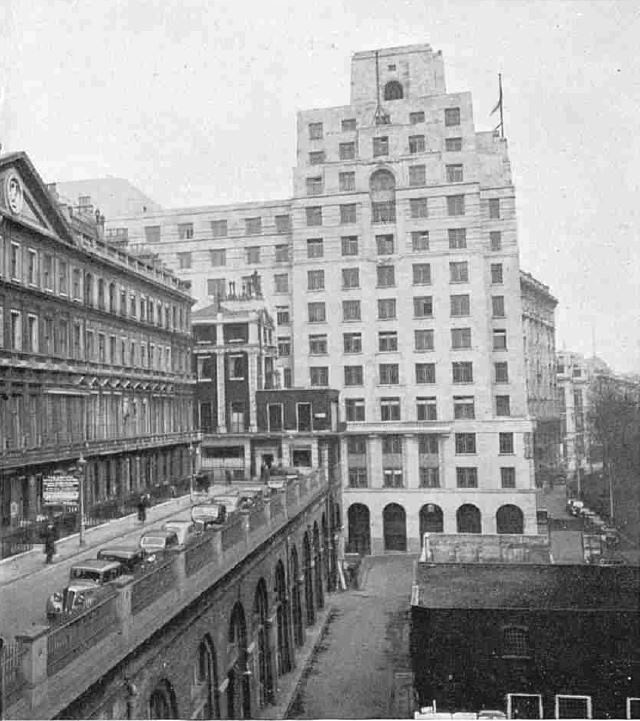

The following photo from just before demolition in 1936 shows the Adelphi Terrace on the left, with the block of houses which would also soon be demolished. In the background is the recently completed Shell Mex House (1932) with Savoy Place running to the lower right of Shell Mex House.

With the construction of the new Adelphi building and terrace, the terrace was pushed forward to also run up against Savoy Place, in line with Shell Mex House, so the area in the lower right of the above photo is now under the terrace.

Another view of Adelphi terrace around 1897 before the construction of Shell Mex House:

If you look to the left of the second lamp post in the above photo, you can just see a round plaque. This was a medallion of the Royal Society of Arts recording the fact that the actor David Garrick had lived in the house. It was in one of the back rooms of the house that the actor died in 1779.

The large building on the right on part of the site now occupied by Shell Mex House was the Hotel Cecil.

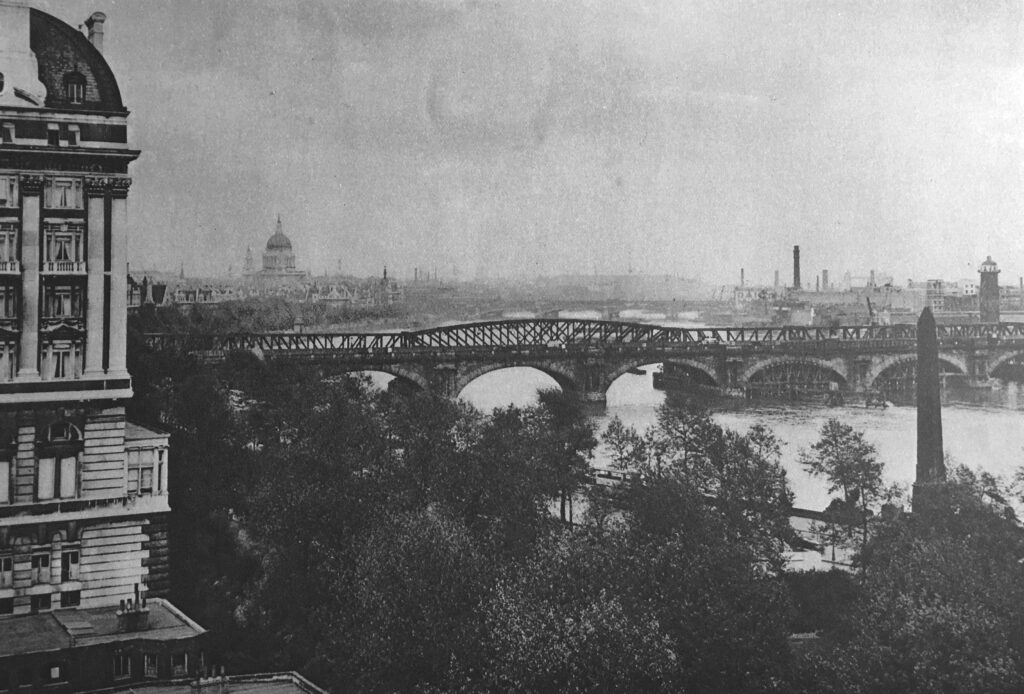

And if you had been living in one of the houses in the terrace, this would have been your view as you looked along the river to the east, with the corner of Hotel Cecil on the left, and the first Waterloo Bridge crossing the river.

At the time of the above photo, the Adelphi was described as “one of the finest places to live in all London, as well as for pleasantness of situation as for convenience. The noise of the Embankment is sufficiently far away, and the hooters and sirens on the river suggest that sense of freedom and open space which goes with ports and their kinship with the sea. All too uncommon in London, late at night, the loudest noise is often the wind in the trees which move the lights of silent shipping“. Not from an early 20th century Estate Agents description, the quote is from the book Wonderful London.

Continuing a walk around the Adelphi building, and more door surround decoration:

Looking back between the wings of the building, we can see bow windows extending outward, with metallic decoration:

More decorative carvings:

Balconies:

The main entrance to the Adelphi on John Adam Street:

What is confusing is if you look above the doors, is the address John Street, however if you look to the lower right, is the full name John Adam Street.

John Street seems to have been the original name, as it is used on the 1895 Ordnance Survey map, and by the time of the 1951 revision, the current full name John Adam Street is used. I suspect the name change was when the Adelphi was built in the 1930s.

Having had a walk around the Adelphi building, time for a look at what remains of Robert Adam’s original estate. This is the view along Robert Street, with a fine terrace of buildings lining the side of the street. The end of the building on the left would have originally faced onto the original terrace, and is the same building at the far end of the terrace as in the 1795 print.

The scheme proposed by the Adams was highly ambitious. The land was sloping down to the river, and indeed consisted of part of the foreshore. The area would often flood at times of high tide.

Rather than building houses down along a sloping plot of land towards the river, with the resulting problems of damp and flooding, the plan consisted of building brick arches with the houses building on the platform created above.

The space within the arches would be sold or leased, and this approach would create a considerable improvement to the embankment of the Thames.

The following print from 1784 shows the completed estate with houses built above the arches which provided storage space easily accessible from the river (© The Trustees of the British Museum).

The plan and construction was ambitious, and the financial side of the project was rather risky, as a lease on the land was only signed a year after construction had begun in 1768, and parliamentary approval to build the new embankment along the river was not granted until 1771.

Costs for the project were so high that the money had run out by 1773 when much of the estate had yet to be completed. To raise additional finance, a method common in the 18th century was used whereby a lottery with 4,370 tickets selling for £50 each raised enough to complete the estate. Prizes for lottery winners included some of the houses on the estate as well as storage space in the arches below.

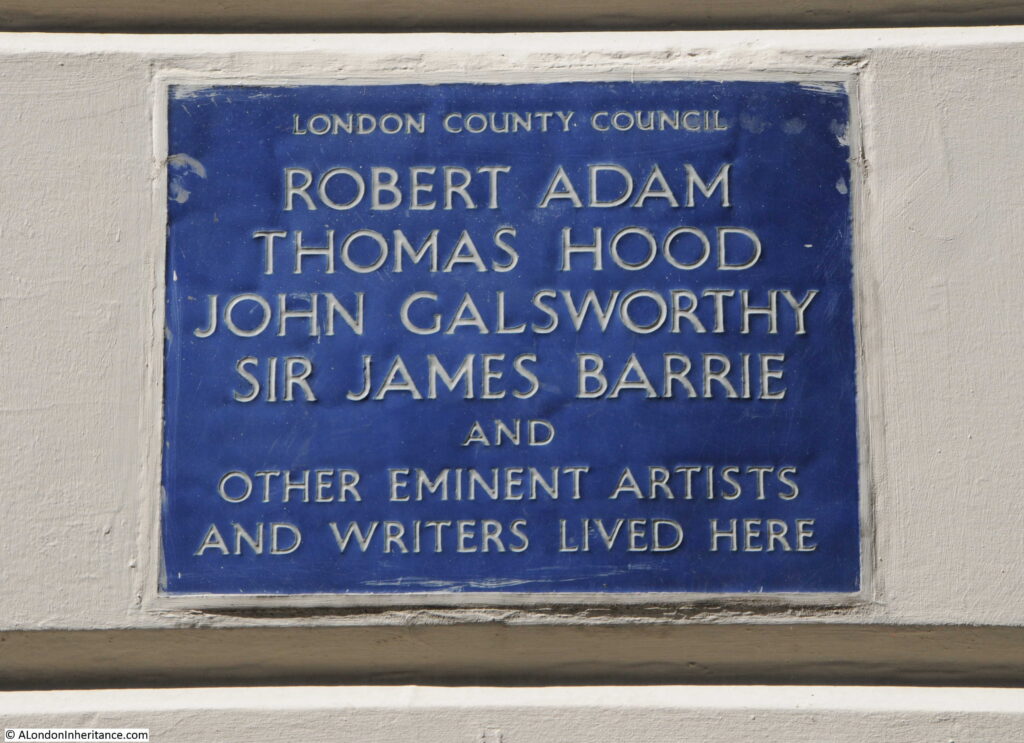

The following plaque on the terrace in Robert Street identifies some of those who have lived in the houses:

View of the terrace in Robert Street from the junction with John Adam Street:

Strange that with street renaming, John Street changed to John Adam Street, however Robert Street kept the original name without a rename to the full Robert Adam.

The houses were highly decorated including Adam fireplaces. Many of the first floor ceilings were also painted by either the Swiss artist Angelica Kauffman or Giovanni Battista Cipriani from Florence.

Walking to the north of the Adelphi, along John Adam Street, and we find this building which was clearly not built as one of the terrace houses:

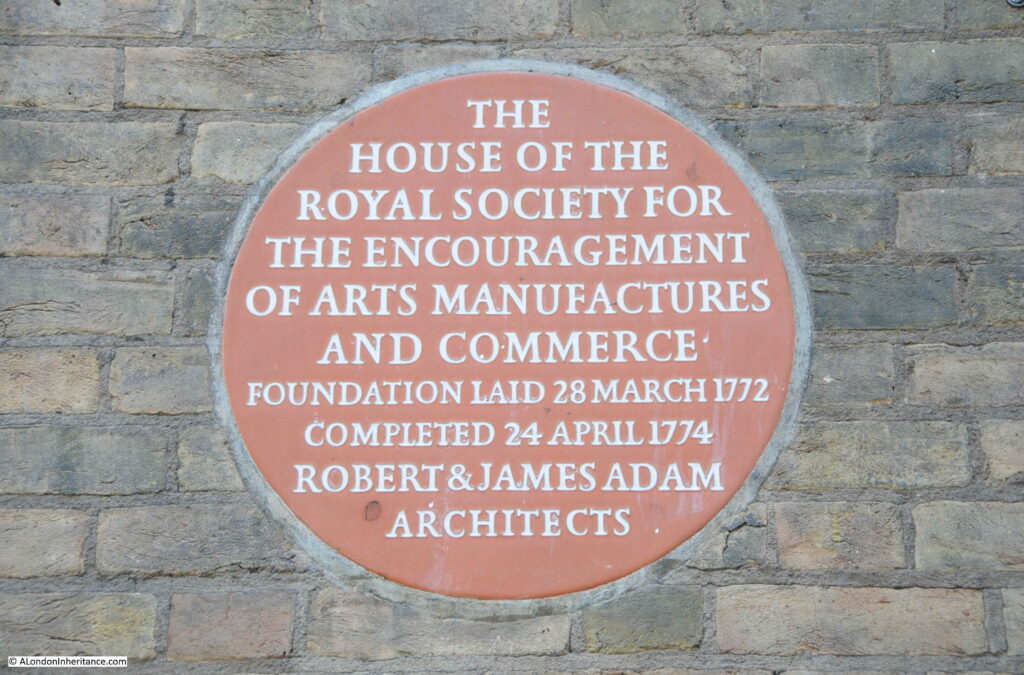

A plaque on the front identifies the building as the home of the Royal Society for the encouragement of arts, manufactures and commerce, which was founded in a coffee house in Covent Garden, and then moved to this building by Robert and James Adam in 1774. The building is still their home.

During the 1930s demolition ready for the construction of the Adelphi, demolition reached to the southern side of John Adam Street, so the street and home of the Royal Society are part of the original build, and the basement of the Royal Society building retains some of the brick arches built to raise the area above the sloping land.

In the 19th century, the arches and vaults below the houses had become somewhat different to what had been intended. The Sketch in 1903 includes the following description “The houses were built on deep arches that rivalled the Catacombs of Paris and these, at one time, were a great thieves kitchen, a tramps paradise, or doss house, that defied Watchmen and Bow Street Runners, and their successors the modern Peelers”.

There is probably some journalistic exaggeration in the above quote, however the following print from the mid 19th century does show a rather dark and gloomy place, underneath the Adam’s terrace houses (© The Trustees of the British Museum):

Looking along John Adam Street to the junction with Adam Street and we can see how the Adam’s plan included focal point houses at the end of the streets, and the type of decoration used.

The building in the background is Shell Mex House. When researching this post and after taking the above photo, I found the following print which shows the Royal Society building on the left, and the same building as in the photo, at the end of the street (© The Trustees of the British Museum).

I should have found the above print before visiting the site as I would then have taken the photo slightly further back to include the Royal Society building. If you stand in the street today, ignore the new Adelphi to the right, and Shell Mex House, the view does look much the same as in 1795.

The following photo is looking up Adam Street. The junction with the Strand is further along the street to the left, with an original house at the end of the terrace with a curved extension to the smaller width of the street. Adam Street was cut through to the Strand as part of Adam’s construction of the Adelphi.

The house behind the white car has a GLC Blue Plaque stating that the 18th century industrialist and inventor Sir Richard Arkwright lived in the house, with English Heritage’s background to the plaque stating that Arwright lived some of the final years of his life here in Adam Street before his death in 1792.

Looking above the houses in the above photo, there is an unusual sight hidden within the dense building of this area south of the Strand. A brick chimney with some robust steelwork providing support from Shell Mex House.

The type of brick chimney seen in the above photo was once relatively common across London, but now is an unusual sight. No idea of the chimney’s purpose, whether it was or maybe still is, part of the Shell Mex House heating system.

That was rather a detour from my father’s original photo of the open air art exhibition in the Victoria Embankment Gardens, but that is why I started the blog, as a means of getting out to find the location of a photo and discovering a wider area.

There is more to the story of the Adam’s brothers and the surrounding area, including the creation of the Embankment Gardens, Shell Mex House, and Lower Robert Street which still routes under part of the estate. The old river stairs that would have entered the river roughly along where Savoy Place is today, and some of the lost streets down to the river – hopefully all subjects for future posts.

And returning to the original photo, I wonder if the little girl in the photo can today remember walking in the gardens and alongside the art exhibition?