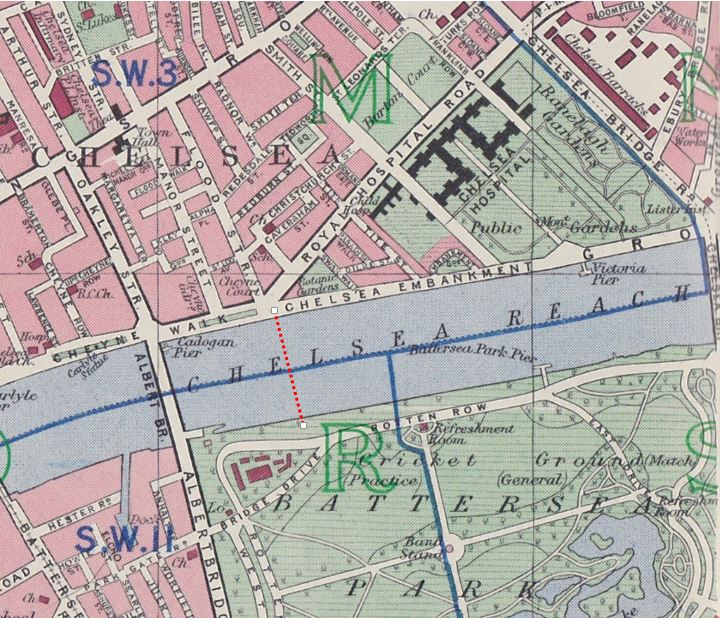

After exploring Cheyne Row for last week’s post, I walked along the Chelsea Embankment towards Battersea Bridge, to photographic the same view as my father’s photo looking along the River Thames towards Albert Bridge, with Battersea Park and Power Station in the background.

The same view today:

In the last half of the 19th century, Chelsea was growing rapidly. The Chelsea Embankment was under construction, the first Chelsea Bridge (originally called the Victoria Bridge) had been completed in 1858 and the nearby Battersea Bridge was of a rather old and fragile wooden construction.

Congestion and the rapid development of the area justified an additional river crossing and in 1860 Prince Albert proposed that an additional bridge between the two existing bridges would be justified by the volume of traffic and the revenue that would be generated by tolls for crossing the bridge. The Chelsea Bridge when opened was a toll bridge and proposals for the Albert Bridge included a toll for crossing the river.

The Albert Bridge Company was formed to build and operate the bridge and construction started in 1870. The bridge was designed by Rowland Mason Ordish using his own patented design. Although construction of the Albert Bridge was approved in 1864, the six year delay to the start of construction (due to plans and work on the Chelsea Embankment), allowed Ordish to design and build another bridge using the same principles – the Franz Joseph Bridge which spanned the River Vltava in Prague.

The following photo of the Franz Joseph Bridge shows how similar the design was to the Albert Bridge, and also probably shows how the deck was suspended – a design that would lead to structural weaknesses in the Albert Bridge resulting in the need for additional strengthening over the years.

Source: By František Fridrich (21. 5. 1829 – 23. 3. 1892) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons)

The Albert Bridge was opened in 1873. The bridge was 710 feet long with a central span between the two towers of 384 feet. The design included toll booths at both ends of the bridge to collect the tolls for crossing the river. The cylindrical piers were the largest ever cast and were manufactured at a nearby metal works on the Battersea side of the river, then floated down to the location of the bridge, sunk in the river and filled with concrete.

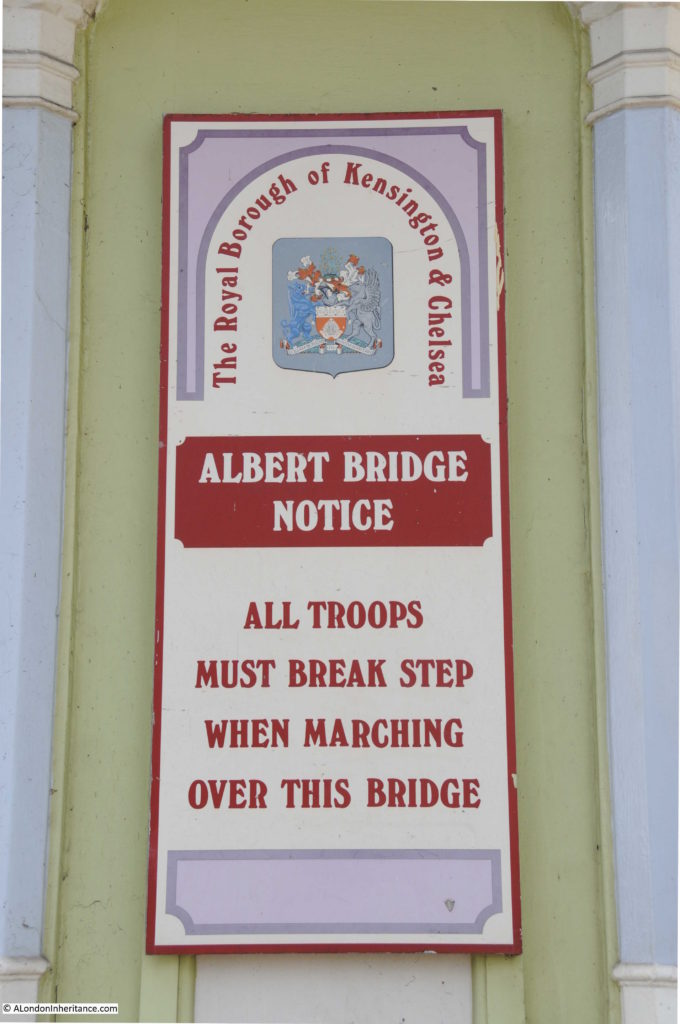

Soon after construction, there were concerns about the strength of the bridge as it would frequently vibrate, a problem which was amplified when large numbers of people walked across the bridge in step – an issue when troops from the nearby Chelsea Barracks crossed the bridge.

The vibration of the bridge was the result of the synchronisation of the steps of those crossing the bridge. The same problem was seen when the Millennium Footbridge opened across the river in June 2000. When upwards of 2,000 people were on the bridge it would start to vibrate. Research has shown that when a bridge starts to vibrate, people walking across the bridge start to synchronise their step with the movement of the bridge, which in turn amplifies the vibration and movement.

Interesting that even after 130 years, the same problems can apply to a structure.

In 1884 Sir Joseph Bazalgette inspected the bridge and found that the iron rods supporting the bridge were showing signs of corrosion and a program of work was implemented to strengthen the bridge which included the installation of steel chains to support the deck along with the replacement of the timber decking.

The steel chains changed the appearance of the bridge from the original design, which probably looked very similar to the Franz Joseph bridge, to the Albert Bridge that we see today.

When I took the comparison photo, I was trying to align features on the bridge with the chimneys of Battersea Power Station to make sure I was roughly in the same position. There were a number of distractions to this.

Firstly, if you look under the Albert Bridge there are a number of piers in the river further back. These are not the piers of Chelsea Bridge, rather they are the piers of one of the temporary bridges constructed over the river during the war to provide additional capacity should one of the main bridges be badly damaged by bombing. I wrote about this bridge in a previous post, and this is my father’s photo of the temporary bridge at Battersea:

But there was another difference looking underneath the bridge – when my father took the original photo the bridge was a suspension bridge, with the central span supported across the river by the chains running from the top of each tower. In my 2017 photo there is a large pier supporting the centre of the bridge.

The central pier was the result of ongoing concerns about the strength of the Albert Bridge. After Bazalgette’s inspection in 1884, as well as the additional strengthening work, he imposed a weight limit of five tons for vehicles crossing the bridge.

There was a proposal to demolish the bridge in 1926 and replace with a new, stronger bridge, however lack of funding meant that this did not progress beyond the proposal stage. A second attempt to demolish the bridge was made by the London County Council in 1957, however a campaign led by John Betjeman saved the bridge again.

The weight limit for vehicles crossing the bridge had been further reduced to two tons in 1935, so clearly something had to be done to strengthen and preserve the bridge.

As well as replacing the decking and strengthening the bridge structure, the answer to significantly strengthen the bridge was to convert the bridge to a more traditional beam bridge by the addition of a central pier. The bridge closed in 1973 for this work to be carried out which resulted in the bridge we see today.

The two new central piers are of the same design as the original piers, however they support a metal girder that runs under, and supports the centre of the bridge:

In echoes of the Garden Bridge, there was also a proposal in 1973 to close the Albert Bridge to traffic and change the bridge into a public park and pedestrian walkway. John Betjeman also supported this proposal, along with many of the local inhabitants who probably saw the closure of the bridge to traffic as a way of reducing the ever increasing volumes of traffic along the Chelsea Embankment. Motoring groups opposed the idea and such was the need for river crossings capable of supporting vehicular traffic that the proposal was rejected and the bridge reopened to pedestrians and traffic after the strengthening work and the addition of the new central piers.

Despite this work, the weight limit has remained at two tons and to try and prevent vehicles over this weight from crossing the bridge a traffic island was introduced at the southern end of the bridge to narrow the entrance, thereby limiting the size of vehicles trying to cross.

The last strengthening work to be carried out was in 2010, and the Albert Bridge will continue to require periodic work to maintain the decking and the supporting ironwork well into the future.

The toll booths at the entrance to the bridge:

The toll booths still retain the signs warning troops to break step when marching across the bridge:

View across the bridge from the north side on a sunny autumn day:

The plaque on the bridge states the bridge was opened in 1874, however the bridge had a phased opening.

The “Shipping and Mercantile Gazette” on the 1st January 1873 reported on the initial opening of the Albert Bridge:

“THE ALBERT BRIDGE AT CHELSEA – At 1 o’clock yesterday, amid the firing of cannon and waving of flags, the Albert Bridge at Chelsea was opened to the public. There was an absence of all ceremony, as the bridge is as yet in an unfinished condition. The opening simply consisted in the admission of the public over the bridge, the engineer, contractor and other gentlemen going over in a carriage. By this event, however, the conditions of the Act of Parliament have been complied with, which required that the bridge should be opened before the close of the year. The work of completion is being rapidly proceeded with, and in a short time the formal ceremony of opening the bridge may be expected to be performed.”

There does not appear to have been a formal opening ceremony, and there are reports in the newspapers of the time of the bridge opening to traffic in September 1873.

The view looking to the east from the centre of the bridge:

And the view looking to the west:

The bridges in the above photos, Chelsea and Battersea Bridges were, as with the Albert Bridge, all originally toll bridges, however soon after the Albert Bridge had opened, it was made toll free along with many other bridges across the river. The East London Observer reported in the 31st May 1879:

“FREEING THE BRIDGES OVER THE THAMES – a great work has just been accomplished in which the East End has co-operated with the West, although its first importance is for the latter. It was but the other day that Waterloo Bridge was thrown open free of toll, and the boon granted is conspicuous by the fact that in seven months the traffic has increased 90 per cent. But last Saturday five bridges were made free of toll for ever, these being the Lambeth, Vauxhall, Chelsea, the Albert and Battersea Bridges.

Within the Metropolis there are thirteen bridges spanning the River Thames and connecting the Middlesex and Surrey shores. With a view of obtaining for the public the full advantage of these bridges as a means of free communication between the various points of the Metropolis, the Board of Works in 1877, promoted a bill in Parliament, to enable them to purchase the interests of the several companies in all the toll bridges crossing the Thames within the metropolis, including the two foot-bridges at Charing Cross and Cannon Street railway stations, and also one bridge crossing the Ravensbourne at Deptford. the bill was successfully carried through both Houses of Parliament, and passed into law in July 1877.”

The Albert and Battersea Bridges were owned by the same company and the sum of £170,000 was paid by the Metropolitan Board of Works to the company for the purchase of the bridges.

From then on, crossing the river was toll free, which must have been one of the drivers to opening up business and trade on both sides of the River Thames, as the article also states that “A free communication across the Thames is an incalculable boon to all classes of inhabitants on both sides of the river”.

Following the opening of the bridges described above, the only bridges across the Thames that still had tolls were bridges at Wandsworth, Putney and Hammersmith.

The view from the centre of the bridge – the style of decoration is the same throughout the bridge, with the round patterns repeated across both sides of the bridge span, and along the edge of the steps that lead up from the river walkway on the north bank of the river.

View from the traffic island on the southern end of the bridge looking back over towards the north:

It is perhaps a wonder that the Albert Bridge has survived so long. A bridge that once had a twin crossing a river in Prague.

A bridge that if the Chelsea Bridge had retained its original name would be one half of the Victoria and Albert Bridges.

And a bridge that may have been the original “garden bridge”.

The Albert Bridge is a unique bridge. The addition of the central pier has changed the design of the bridge to a more traditional beam bridge, however on a sunny autumn day it still appeared as London’s most beautiful bridge across the Thames.