The Exhibition of Industrial Power and London Archaeology – two completely unrelated topics in today’s post. The first, I will come to in a moment, whilst London Archaeology is the first post of the month “Resources” feature, where I look at some of the resources I use, and which you may also find helpful, to understand and explore London’s long history. London Archaeology resources will be at the end of the post.

But first, if you have been reading the blog for some years, you will know I have an interest in the 1951 Festival of Britain.

Just six years after the end of the Second World War, the Festival was a huge undertaking in terms of planning, resources, construction. etc. at a time when the country was very short of these resources along with the cash needed to pay for a festival.

There were many who argued, with some justification, that all the resources and money would be far better spent on the rebuilding that the country still urgently needed.

The Festival of Britain was though intended to help show the country both to the nation and to the rest of the world. The long history of the country and its people, the arts, design, creativity, science, industry and manufacturing capabilities of the country.

Designers, sculptors, authors, architects all contributed to show a very different post-war world, an optimistic view of the future after years of war and rationing.

Whilst the South Bank exhibition was the main festival site, and the place that is most commonly associated with the Festival of Britain (and where the Royal Festival Hall is today one of the few, physical survivors of the festival), the Festival covered the whole country.

There was a Festival Village, a touring exhibition on an old aircraft carrier, football matches organised with European teams, music and literary festivals etc. all branded with the Festival of Britain design.

There were seven main festival sites:

- The main South Bank Exhibition

- The Exhibition of Science in South Kensington

- The Exhibition of Architecture in Poplar, East London

- The Festival Ship Campania, which toured major ports around the country

- The Travelling Land Exhibition which went to Birmingham, Leeds, Manchester and Nottingham

- The Exhibition of Industrial Power in Glasgow

- The Ulster Farm and Factory Exhibition in Belfast

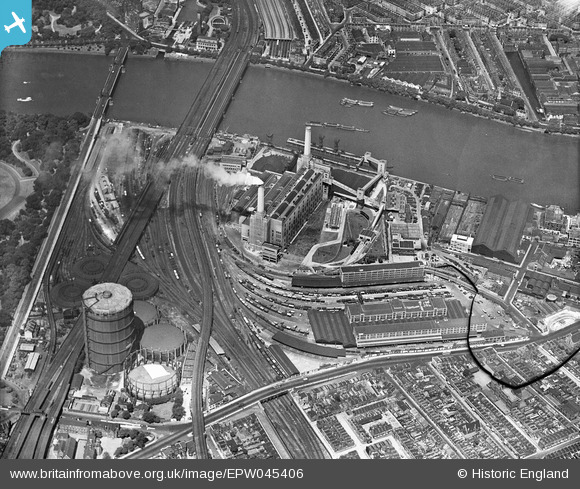

In London, there was also the Festival Pleasure Gardens at Battersea, not one of the exhibition sites, but a major, and well visited part of the festival where there were gardens, rides, illuminations after dark, cafes and restaurants etc.

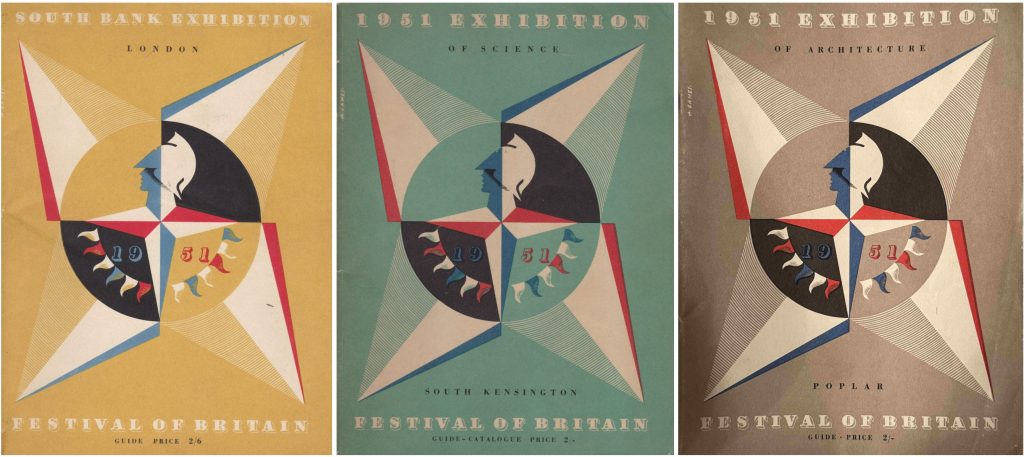

The main exhibitions each had their own guide book. These were detailed guides to the exhibition, and contained a wealth of information on the exhibits and wider context of each respective exhibition.

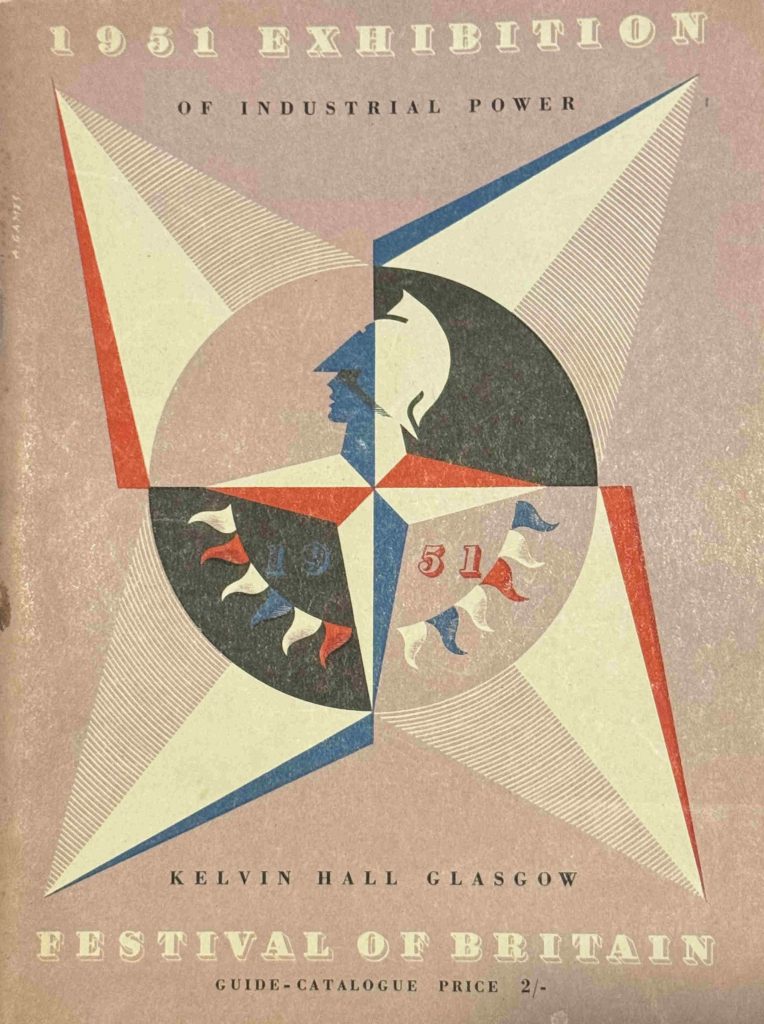

Each guide book had the Abram Games designed Festival of Britain emblem on the front cover, but with a different colour background for each exhibition, with the rest of the guide following the same style and approach to content.

The guide books provide a wealth of information on not just the Festival of Britain, but also the country in 1951, and I have been trying to collect one of the guide books for each festival site, and I recently found one of the two that I am missing.

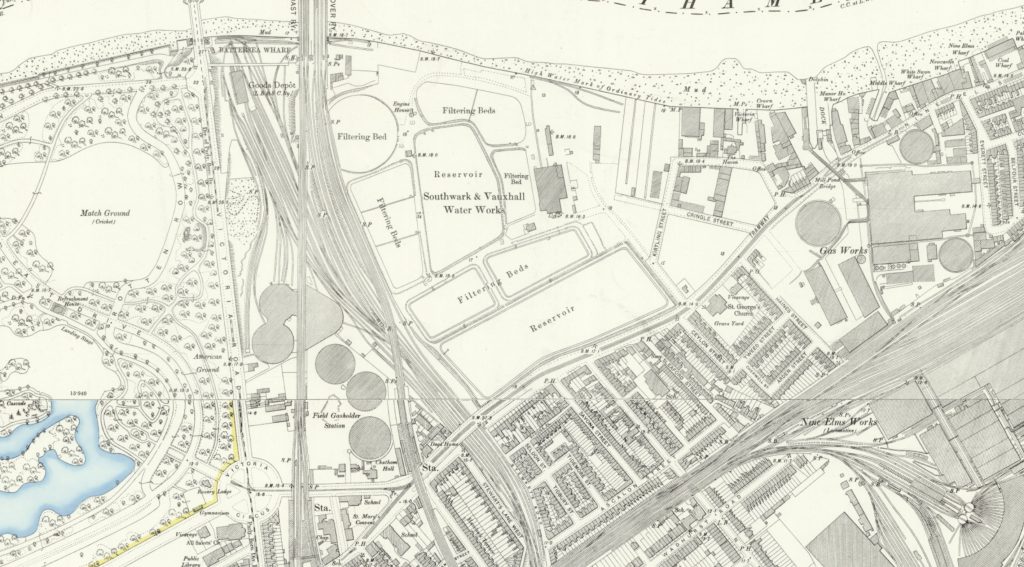

The guide book cover for the 1951 Exhibition of Industrial Power at the Kelvin Hall, Glasgow:

My other guide books are shown in the following images, the first three are the South Bank, South Kensington Science Exhibition, then the Exhibition of Architecture at Poplar:

My final three are the Festival Ship Campania, the Touring Land Exhibition, and then the Pleasure Gardens at Battersea:

There is now only one of the main Festival of Britain guide books that I need to find, the Ulster Farm and Factory Exhibition held in Belfast. This guide book follows exactly the same format as the main guide books shown above. I have seen a couple in exhibitions, but have never found one for sale.

Next year is the 75th anniversary of the Festival of Britain, and it would be great to find the Belfast guide by the end of the year.

I have written about the other exhibition sites in previous posts over the years, and will now look at the Glasgow Exhibition of Industrial Power.

The guide book starts with some background to the exhibition:

“In common with the other Festival exhibitions, Industrial Power is not a trade fair. Nowhere in these halls will you find stands set aside for commercial exhibitors. The exhibition has been planned, from the turnstiles to the exit, to tell a story – the story of Britain’s tremendous contribution to heavy engineering. It is a story which concerns not only machines, but the men who made them. It sets out to show not only British inventiveness, but the effect it has had on the world. Against this background are shown the outstanding products of British heavy engineering in the present day.

The theme is simple. Heavy engineering is the conquest of power. There are two main sources of raw power used by heavy engineering today. They are coal and water. There is therefore a coal sequence and a water sequence which unite towards the end of the exhibition in the Hall of Railways and Shipbuilding.”

The exhibition was visited by Princess Elizabeth, the future queen, in June 1951, however in a reminder that although this was six years after the end of the Second World War, the country was still involved in the Korean war, as in the same report of the princess visiting the exhibition, she also “included at her own special request a visit to soldiers wounded in Korea who are now in Cowglen Military Hospital, where she had a rapturous reception”.

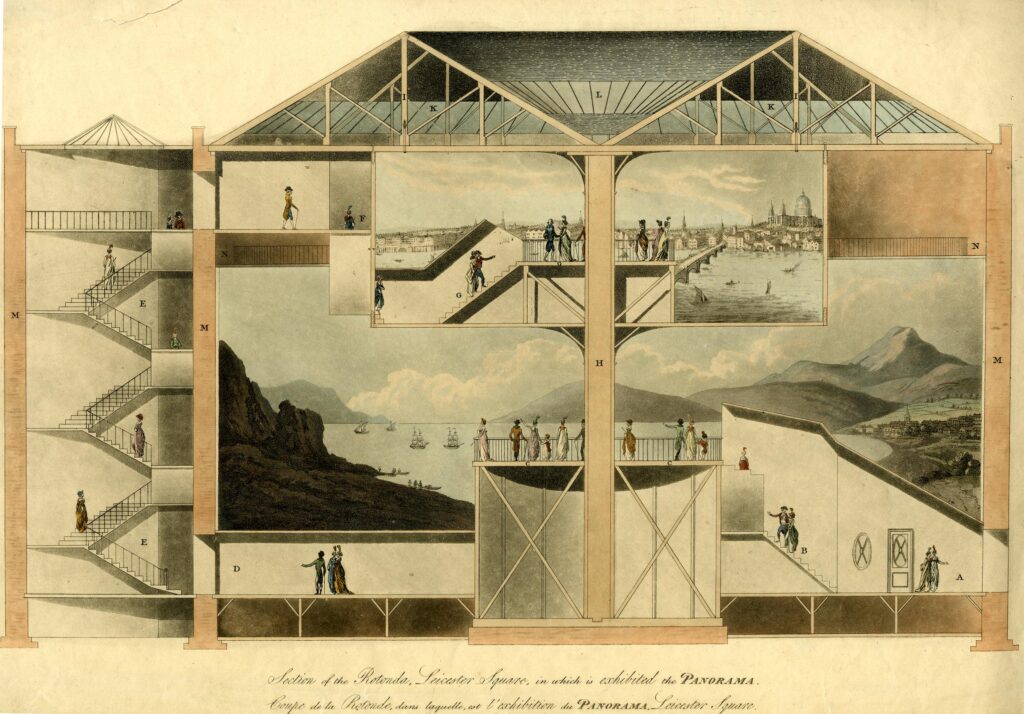

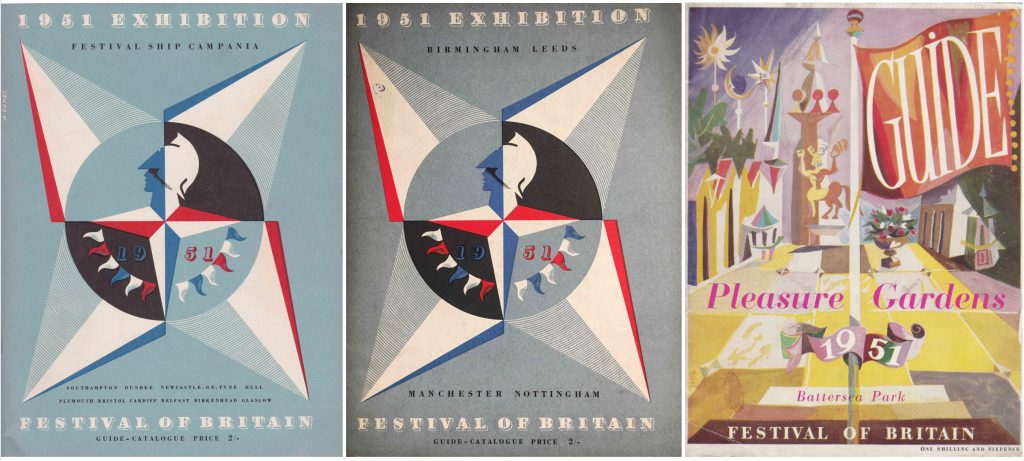

As with the other exhibition sites, at Glasgow, the story was presented to the visitor as they walked through a series of Halls which focused on individual aspects of the overall theme. Walking through the Glasgow exhibition, there was a Hall of Power, of Coal, Steel, Power for Industry, Electricity, Railways and Shipbuilding, Irrigation and Civil Engineering and Hydro-Electricity.

The final part of the exhibition was the Hall of the Future, which offered a vision of a source of power for the future.

The route through the exhibition and the individual halls is shown in the following plan from the guide:

A very vivid example of how the country has changed since 1951 was that coal was a central theme of the Exhibition of Industrial Power, as coal was the main energy source for almost all British industry, electricity generation and domestic energy use.

The Hall of Coal celebrated this fact, and the intention of the displays were to leave the visitor with evidence that:

- Coal sets the wheels in motion and keeps Industry thriving

- Coal is the basis of the Machine Age

The displays took the visitor from the geological formation of coal, where plants took energy from the sun, through to the process of mining coal, and to help with providing the visitor with the experience of mining coal, there was an artificial mine as part of the exhibition.

To make the experience as real as possible, there were two National Coal Board cages which could take 30 visitors each. There was a descent of only 16 feet to the “mine”, however to make this as realistic as possible, the descent commenced with a jerky start to simulate a big drop, then a slow descent and a sudden stop at the bottom.

Having reached the artificial mine, visitors would see a full sized section of a modern, 1951 coal mine, complete with working machinery, manned by a team of Scottish miners.

As well as the modern mine, there were also historical displays showing how mining had evolved, including when children and women formed a significant part of the mining workforce, when miners had to descend to the coal face hanging on a chain rather than within a cage, the role of a 17th century fireman who would descend to the mine at the start of a shift, wrapped in wet rages, to set fire to the gas that had accumulated and clear the workings.

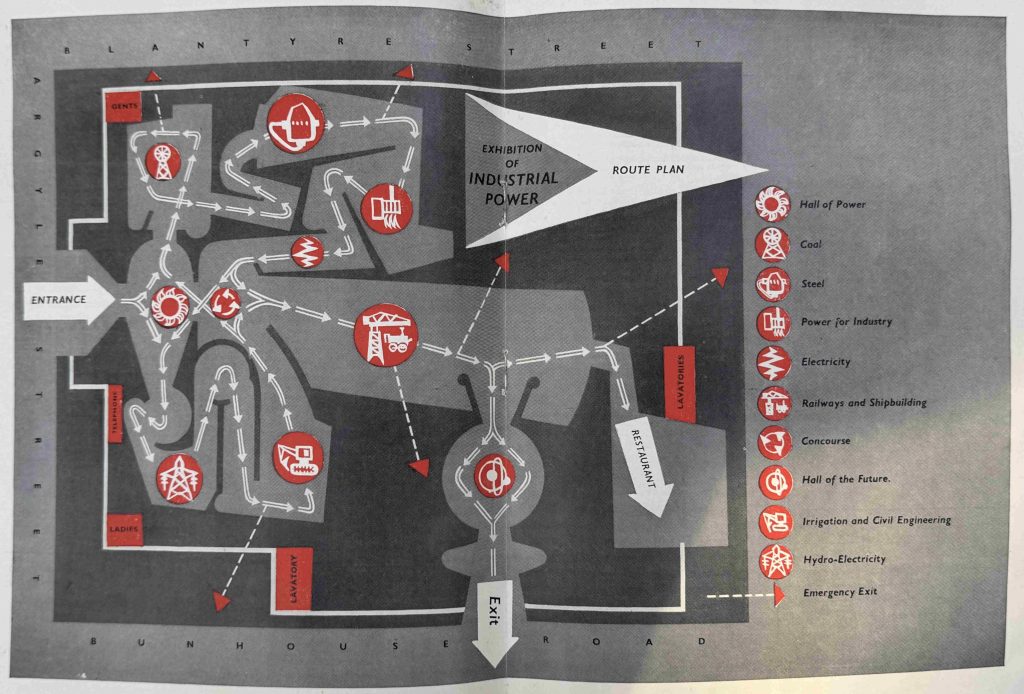

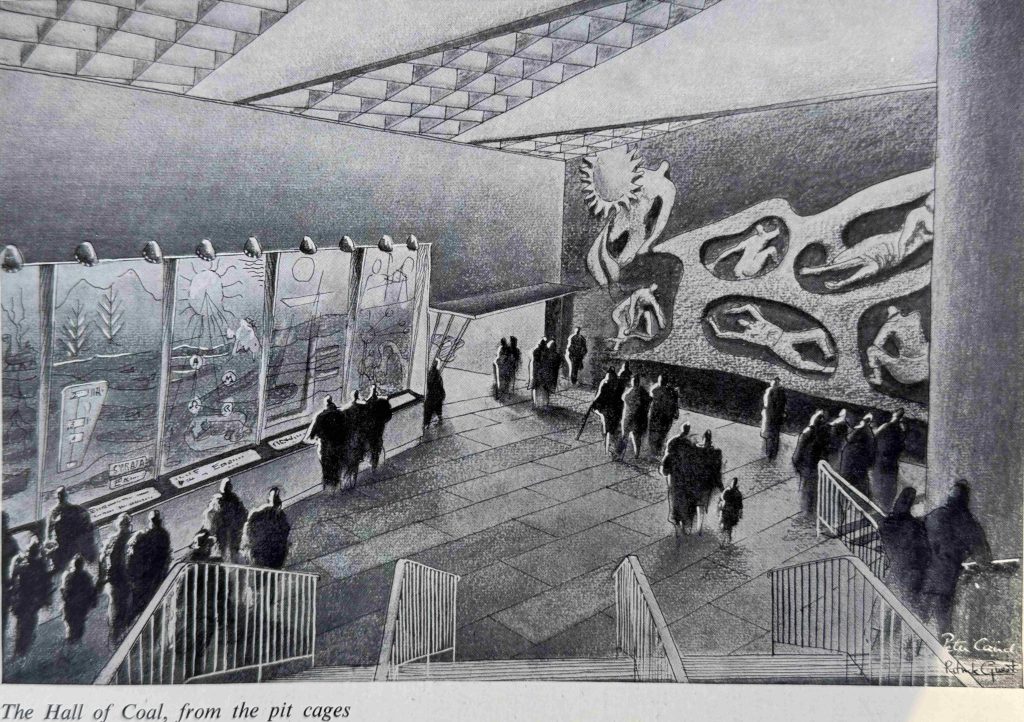

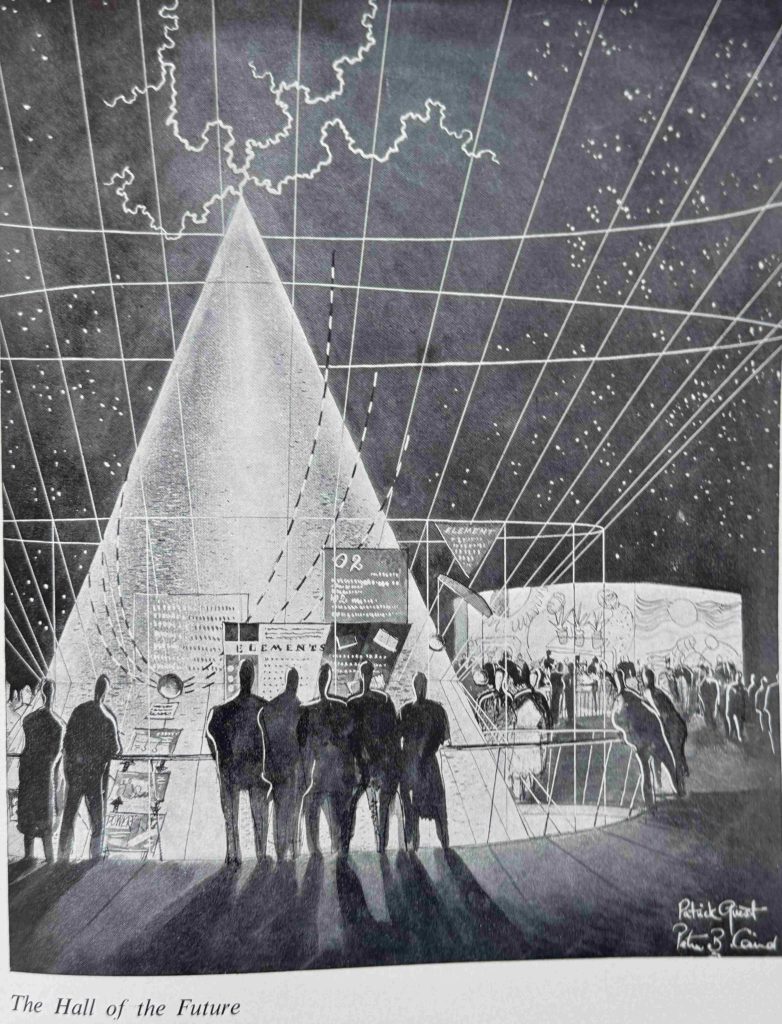

Unfortunately, there are no photos of the exhibitions in the guide as it was published in advance of opening, however it does contain drawings of the some of the halls and exhibits.

This is the Coal Cliff in the Hall of Power:

And the Hall of Coal from the pit cages:

The approach to how information was presented, the mix of physical objects, illustrations, sculpture, reliefs, lighting, written descriptions and the theme of taking the visitor on a journey was the same in Glasgow to all other Festival of Britain exhibitions, including that on the South Bank, although in Glasgow the exhibition was dedicated to power and heavy industry.

What these black and white illustrations do not convey is the use of colour throughout the exhibition. For example, as part of the display showing how coal is formed, there was a symbolic sun, created by bright, pulsing bulbs, to represent coal’s origin in heat.

The other halls followed a similar approach, with the Hall of Steel covering the historic development of the material from the work of Darby, Huntsman, Cort, Neilson, Bessemer, Siemens, Brearley and Hadfield, the “fathers of the steel industry” as the exhibition described them, through to the processes used to produce steel in 1951, the modern machinery and working practices.

The Hall of Electricity again starts with the discovery of electricity: “Electricity is invisible, and can be measured only by its effects. That is why it remained hidden for so long, a latent force in human history, its power unsuspected“, and then runs through how electricity is generated, the modern power station, and uses Sir Charles Parsons as a central figure in the development of large scale generating systems.

The Hall of Hydro-Electricity told the story of places throughout Scotland where the flow of water is used to generate electricity. The last section of the hall covered the Severn Barrage, a proposed project to make use of tides on the River Severn to generate large amounts of electricity.

Generating electricity from the large tidal range of the River Severn has been an on / off proposal for the last 75 years, since the Festival of Britain, and the Severn Estuary Commission reported in March 2025, their recommendations that such a tidal project was feasible.

I suspect that there will still be discussions on such a project in 75 years time.

The Hall of Shipbuilding and Railways included “a great ship-like structure that runs the length of the hall”.

As with all the halls, the story of the development of shipbuilding and the railways was told, starting from first developments through to the latest technology, and the displays included “a magnificent locomotive which will be exported to the Government of Victoria when the exhibition closes”.

Rather ironically, given the exhibitions focus on industrial power, Scotland was suffering power cuts in 1951, and on the 15th of June, 1951, many Scottish newspapers reported that “Exhibition Plunged In Darkness. The £400,000 Exhibition of Industrial Power at the Kelvin Hall, Glasgow, was plunged into darkness for almost an hour today by an unexpected power cut. Visitors who had just entered the hall to tour the exhibition were left standing in total darkness where a few seconds before they had been gazing at vivid artificial lightning flashes”.

Power cuts appear to have been common throughout Scotland in 1951, later in June the Paisley Daily Express was also reporting that Paisley, along with most parts of the country were suffering power cuts for more than an hour, that there was a ten percent voltage reduction, and that the exhibition in Glasgow again suffered power cuts.

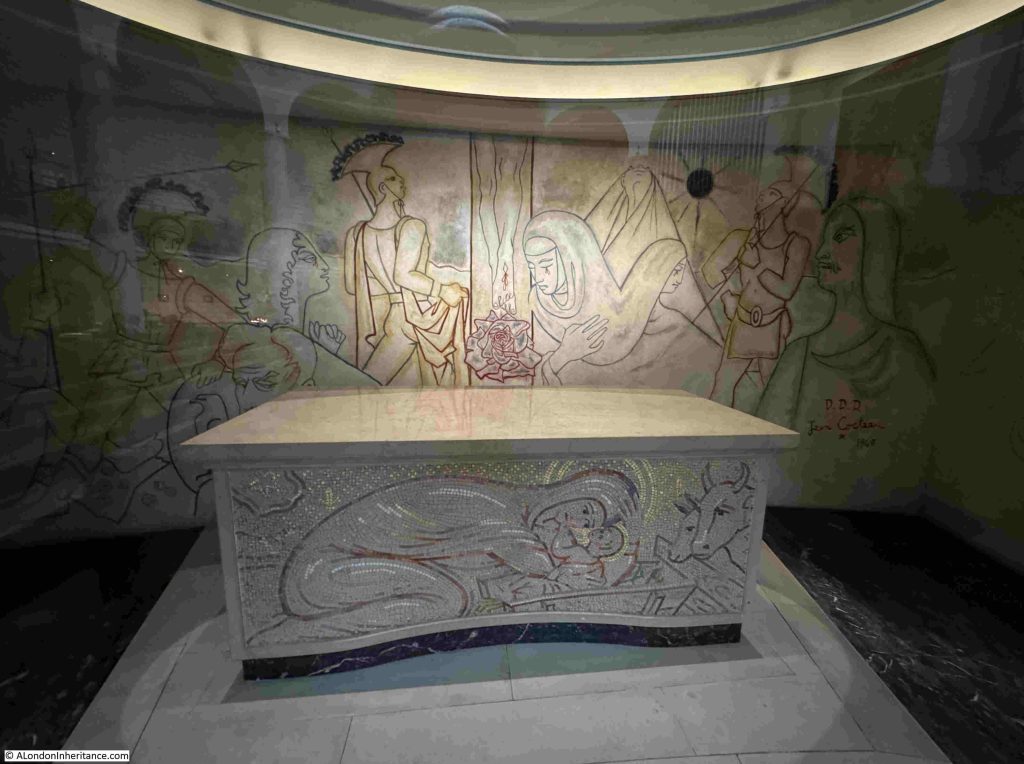

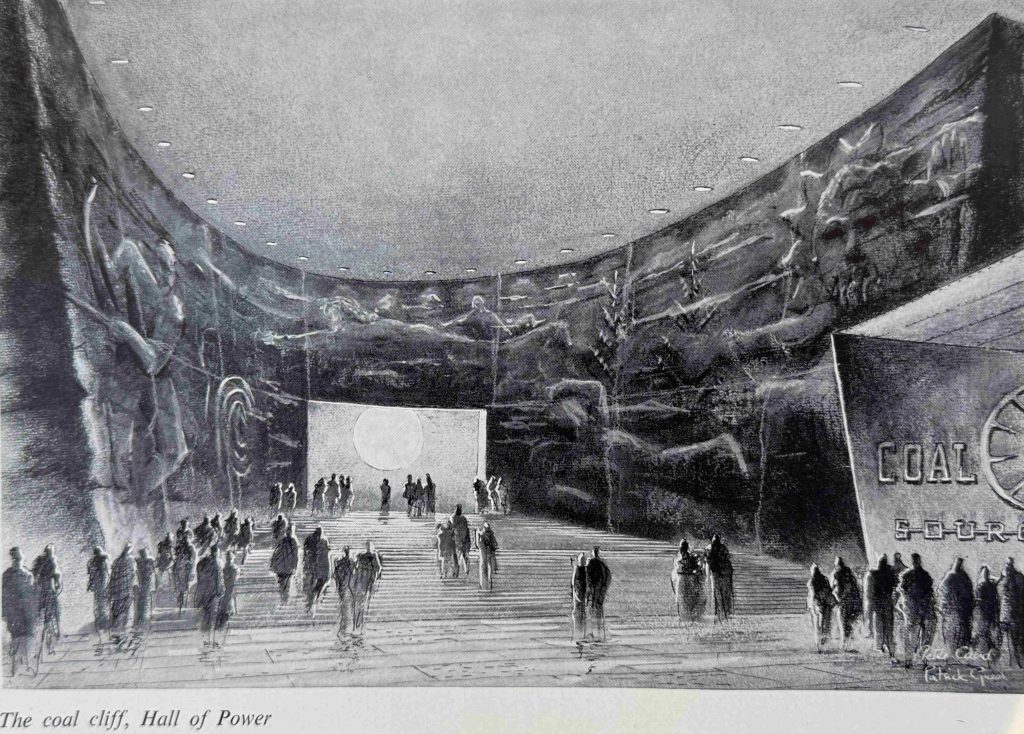

The final hall before visitors left the exhibition was the Hall of the Future.

In this hall the visitor looked down into five pits, each of which covered one of five men who influenced heavy industry in the past, or may do so in the future. These were Watt, Trevithick, Faraday, Parsons and Rutherford, and above the pits a shining cone flashes lightning and represents the limitless future through the promise of nuclear power.

The Hall of the Future:

The design of the guidebook for the Exhibition of Industrial Power was identical to the other Festival exhibitions, whether on the Southbank, Poplar, or the Festival Ship.

The text was intended to educate, and did not (to use a modern phrase), “dumb down” or patronise the reader, but it was also of its time.

As with all the other exhibition guidebooks, the one for Glasgow included a range of colour adverts for companies who had provided their products for exhibition, or who were involved in the theme of the exhibition, so we have Wolf Electric Tools:

English-Electric (with the advert also emphasising the use of coal as a source of energy):

Another common theme of all the exhibition guide books is that the majority of the companies advertising in the books have long since either closed or been take over by foreign competitors, and the adverts from the Exhibition of Industrial Power show just how much the decline of heavy engineering and manufacturing industry in general has been in the last 75 years.

Conveyancer Fork Lift Trucks:

Another advert for English-Electric, this time about their expertise in hydro-electric power:

John Brown shown in the following advert was a major Scottish industrial company, which included a significant presence in marine engineering and ship building. The company built multiple war ships and the liners Queen Elizabeth and Queen Elizabeth 2.

After a series of mergers, the engineering part of the company was taken over by Kvaerner in 1996, who closed the engineering works in 2000, and the Clydebank shipyard ended up as part of the French Bouygues Group in 1980, who closed the business in 2001.

Thomas Smith & Sons – one of the major industrial crane manufacturers of the country and with a significant export business. Their cranes were also used on docks throughout the country, so were probably to be found in the London Docks.

Again, after a series of mergers and take overs, the company has all but disappeared, but there is a very small part of the business surviving within another group, but not at all recognisable to a visitor to Glasgow in 1951:

The British Oxygen Company:

The British Oxygen Company started off in 1886 as Brin’s Oxygen Company after the two French brothers who founded the company – Arthur and Leon Quentin Brin. The company was renamed the British Oxygen Company (BOC) in 1906.

In the early 2000’s BOC was one of the largest industrial gas suppliers in the world, however a few years later, the company was purchased by the Linde Group of Germany.

Interestingly, BOC’s former head office in Windlesham, Surrey was apparently designed in the form of an Oxygen molecule.

The following is from Google Maps and I think I can see the similarity (the map may not appear in the emailed version of the post, go to the website here to view):

Crompton Parkinson, a major manufacturer of electrical power equipment:

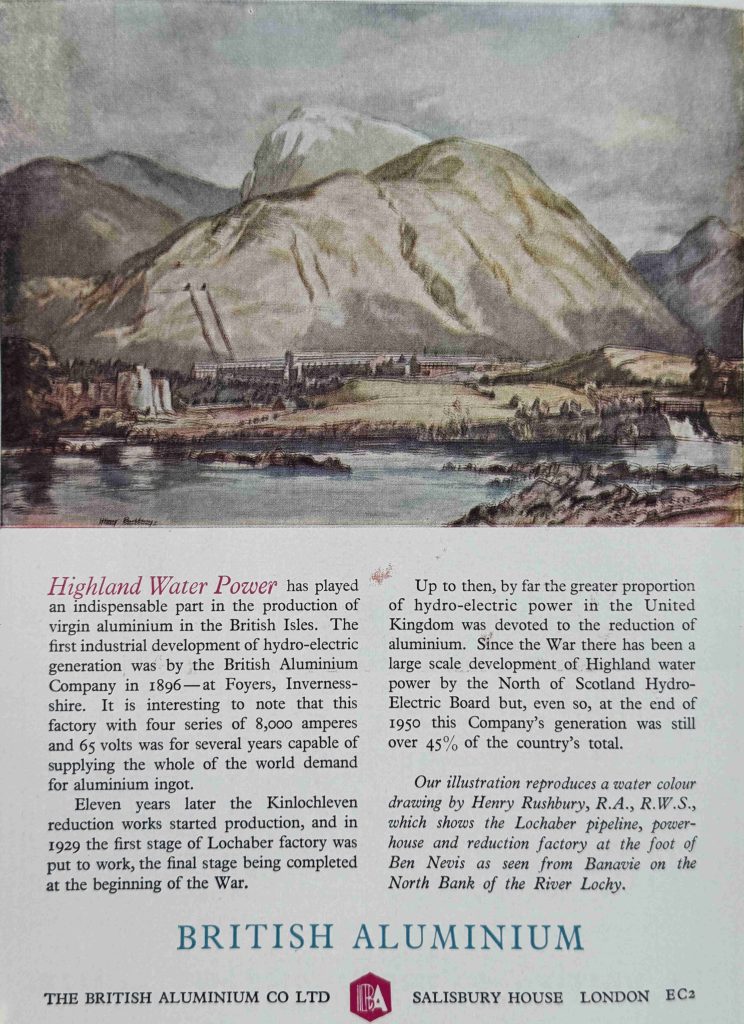

British Aluminium – another company that has disappeared, however the Lochaber hydro-electric plant and pipelines shown in the illustration in the advert are still in use, generating electricity for an aluminium smelter owned by Alvance British Aluminium, the one remaining aluminium smelter in the UK:

The Standard Vanguard:

Thomas W. Ward Ltd – a steel working and construction company, who also had a major business in ship breaking:

In the Hall of the Future, the future of power was through the potential of atomic power and the splitting of the atom. John Laing advertised their work in building and civil engineering with the construction of the Atomic Energy Establishment’s Windscale Works, today known as Sellafield. Today, John Laing are more of an infrastructure investor, rather than a construction firm.

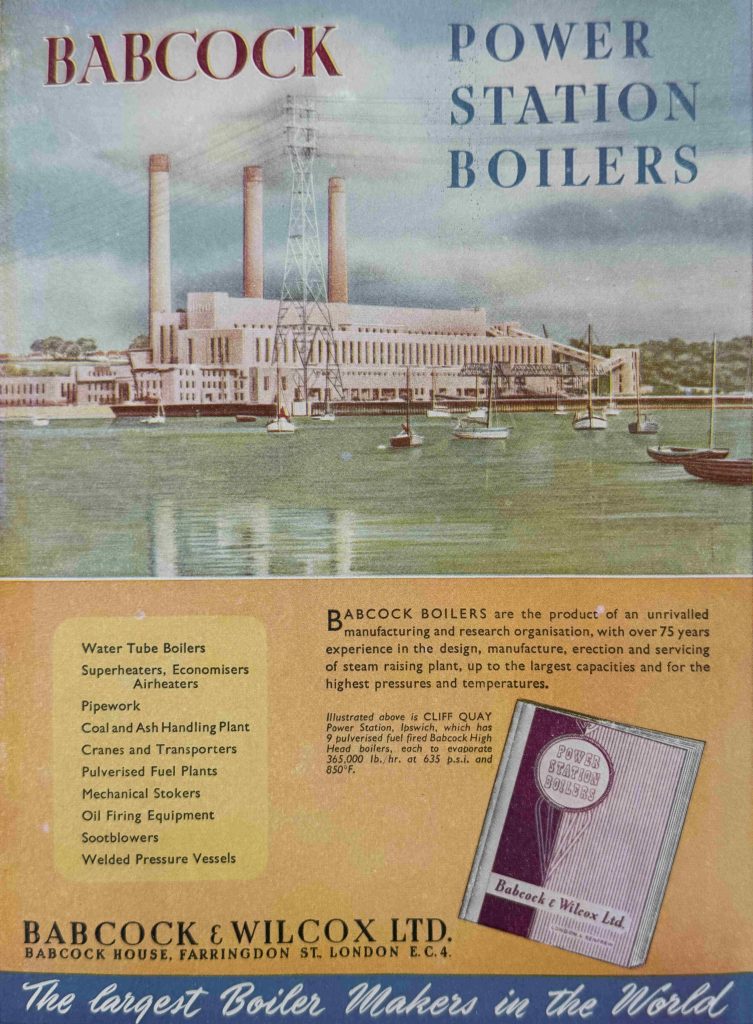

Babcock – once a major manufacturer of power station equipment. industrial and marine boilers, and many other heavy industrial products, today they are more a defence equipment supplier, including naval ships, ground vehicles, equipment support etc:

The Exhibition of Industrial Power was not as popular as the organisers expected, with attendances averaging between 1,500 and 3,500 a day.

The following is typical of the news reports of the time:

“MOST DISCUSSED EXHIBITION IN SCOTLAND – In three weeks the Exhibition of Industrial Power in Glasgow’s Kelvin Hall comes to an end. If nothing else, it has been the most discussed exhibition ever held in Scotland. And perhaps even more remarkable is the fact that many of those who have joined in the discussion have never visited it to see what all the talk is about.

Why haven’t the crowds flocked in? That is not merely a puzzle to the organisers – it has perplexed all manner of people. ‘Too technical’ say some. ‘Not technical enough’ declare others. ‘ A designers dream’, ‘A designers nightmare’.

So the conflict of opinion has swayed back and forth – in speeches, conversation and correspondence. Many have averred that it is not a woman’s show, yet many women who have visited the Hall have been full of praise for what they have seen.

Flattering too have been comments of overseas visitors, many of whom had already toured London’s South Bank. ‘Better laid out’, ‘More compact’. ‘a wonderful achievement story’ – comments such as these have been made.

The great mystery of 1951 still remains unsolved. Soon the Exhibition will be only a memory but it seems not unlikely that it will live on as a debating point for a long time to come. And even yet the missing thousands may materialise in a final rush to see for themselves the cause of all the commotion.”

There were incentives to visit the exhibition, for example, specific tickets winning a prize of a paid trip to the South Bank exhibition in London, so on the 10th of July, Mr John Campbell of Glasgow won a free air trip to London to visit the South Bank as the 150,000 visitor to Glasgow.

There were also organised trips to the exhibition from across Scotland. These included school trips, as well a trips organised by local Labour party organisations, for example the Arbroath Labour Party organised a visit for 300 in June, which included the provision of a special train to take visitors to Glasgow.

Overall, the Exhibition of Industrial Power was considered a success. There seems to have been a good number of international visitors as one of the apparent achievements listed was the amount of foreign currency brought in during the exhibition.

After closure in October 1951, many of the items were taken back by their manufacturer, some were auctioned off, others were scrapped.

I have not found any photos of the interior of the exhibition, however the following film does show the exhibition being opened by Princess Elizabeth, and a brief walk around some of the exhibits:

The Festival of Britain guide books help to illustrate just how much the country has changed in the last 75 years.

The Glasgow Exhibition of Industrial Power shows just how significant has been the decline and loss of heavy engineering and manufacturing. A loss that did not just impact businesses, but has also had a significant social impact in multiple old industrial areas of the country – a social impact which is still very present.

Now I just need to find the Ulster Farm and Factory exhibition guide book to complete the set.

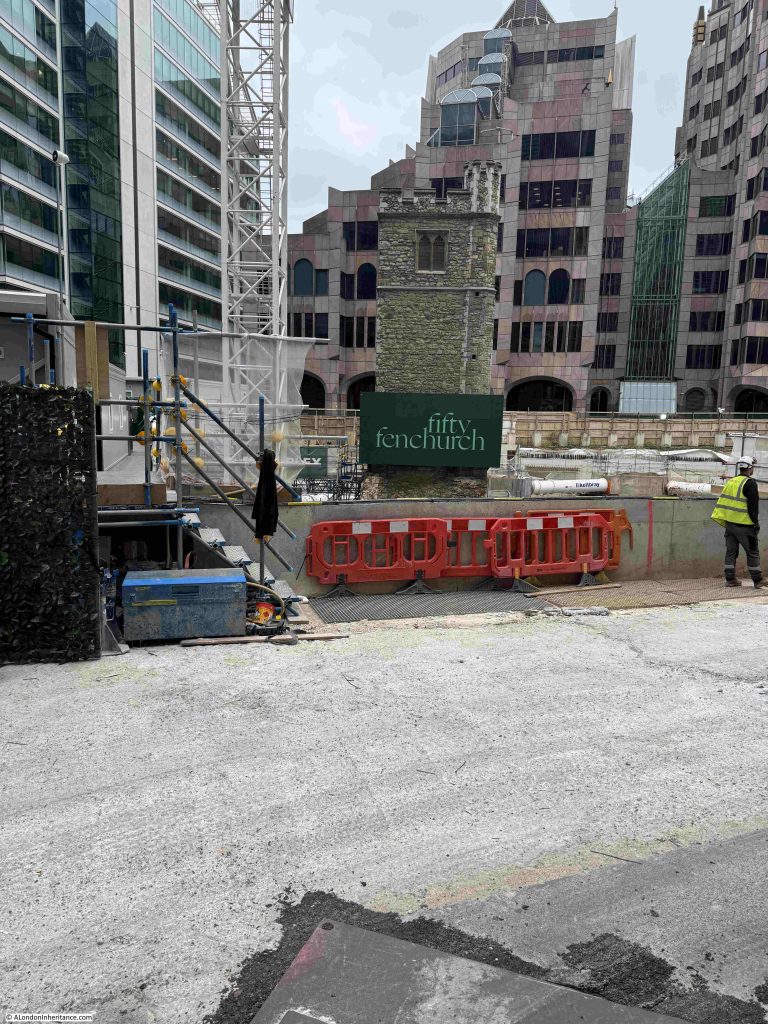

Resources – London Archaeologist and the Archaeology Data Service

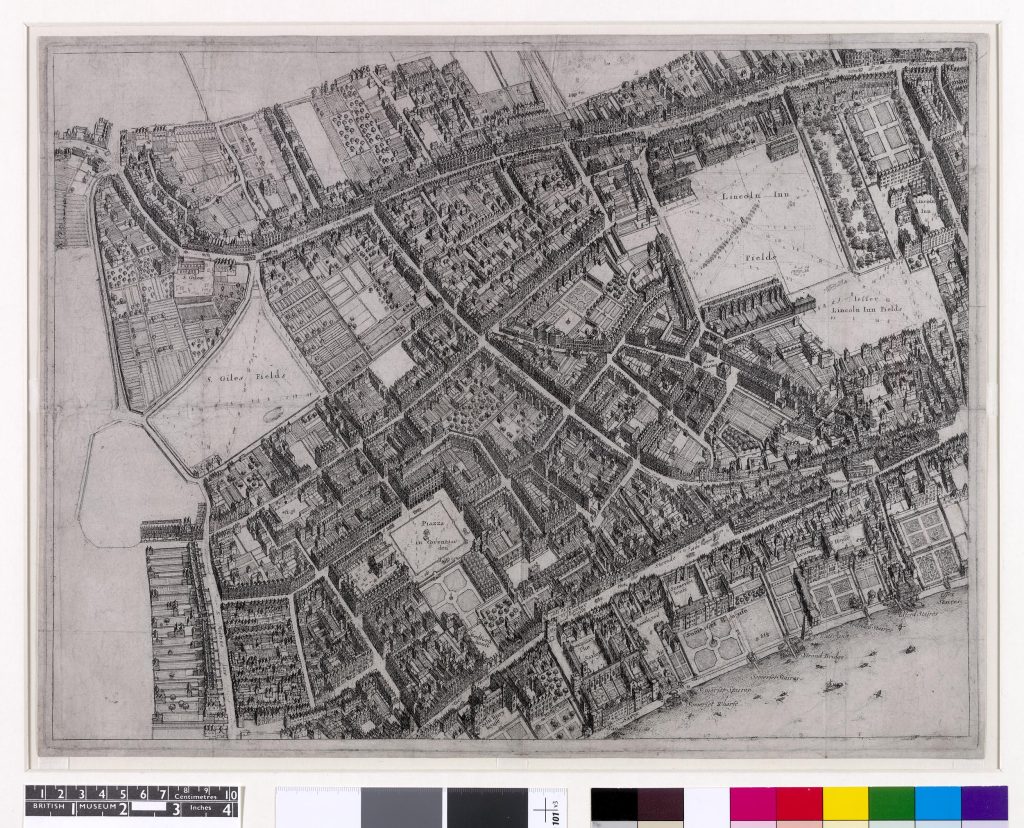

Archaeology is the way we understand so much of London’s physical past, along with the lives of people who once lived in the city. Despite how much the city has been redeveloped over the past few decades, and indeed has been through very many developments over the centuries, there are always new finds that help to tell the story of London’s long history.

Whilst major discoveries make the local and national news, that is plenty more that does not, but which deserves a bit more publicity.

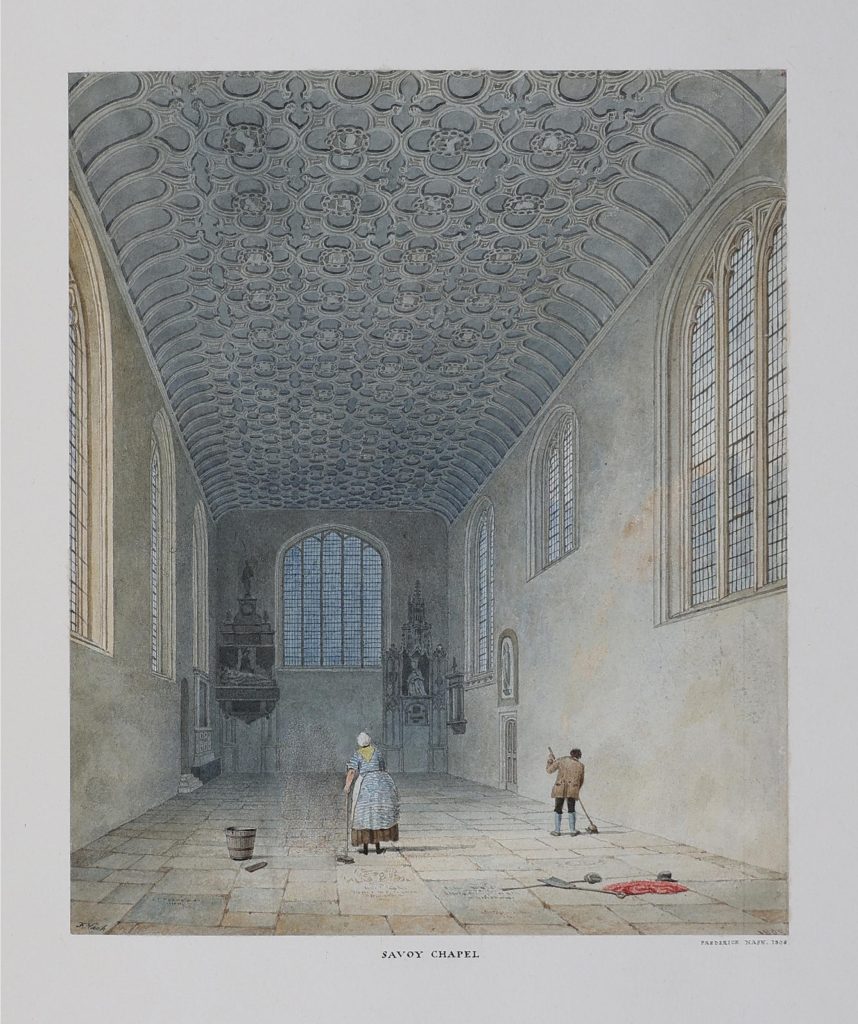

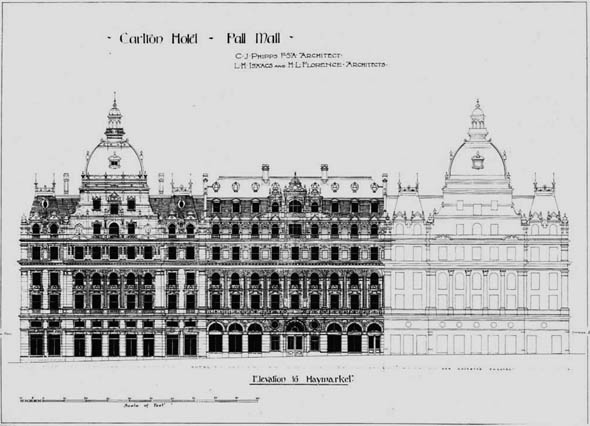

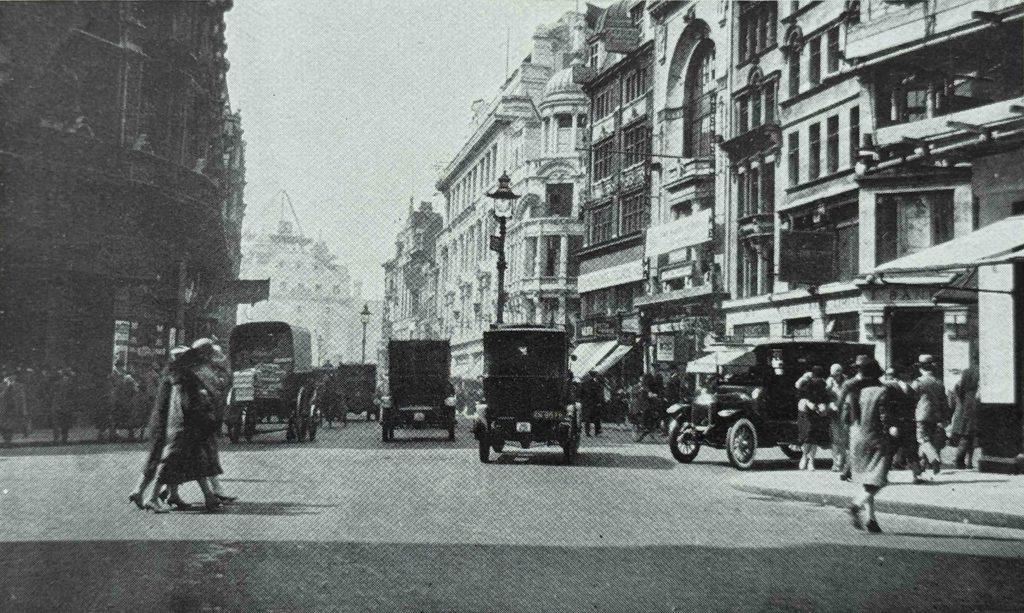

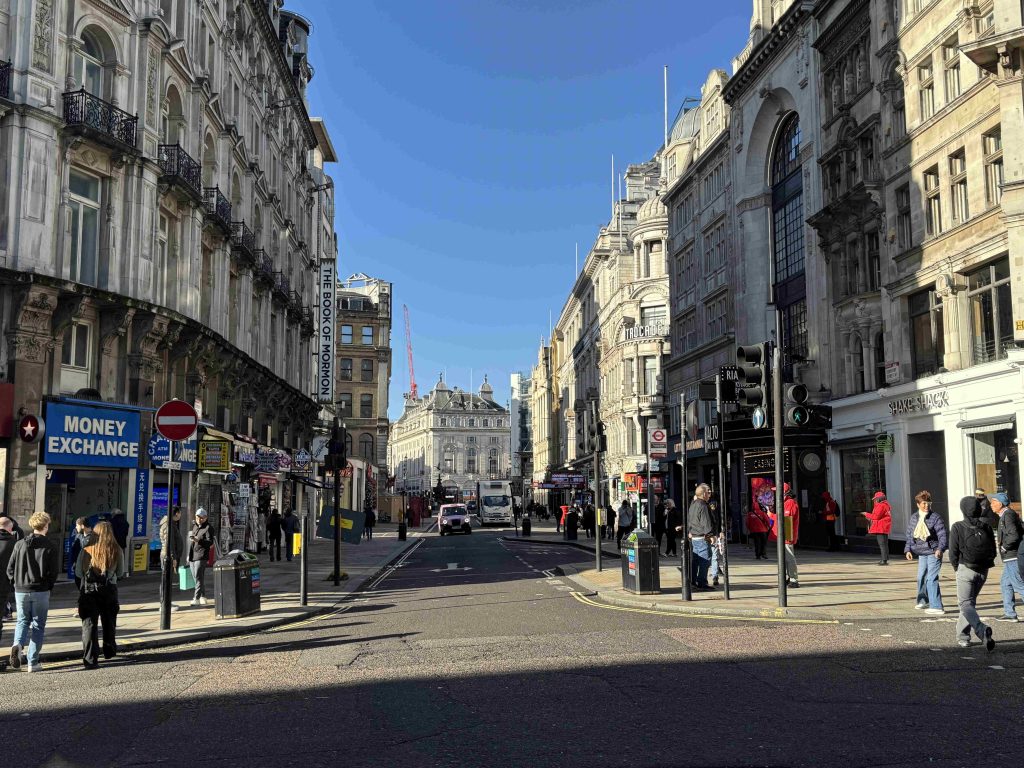

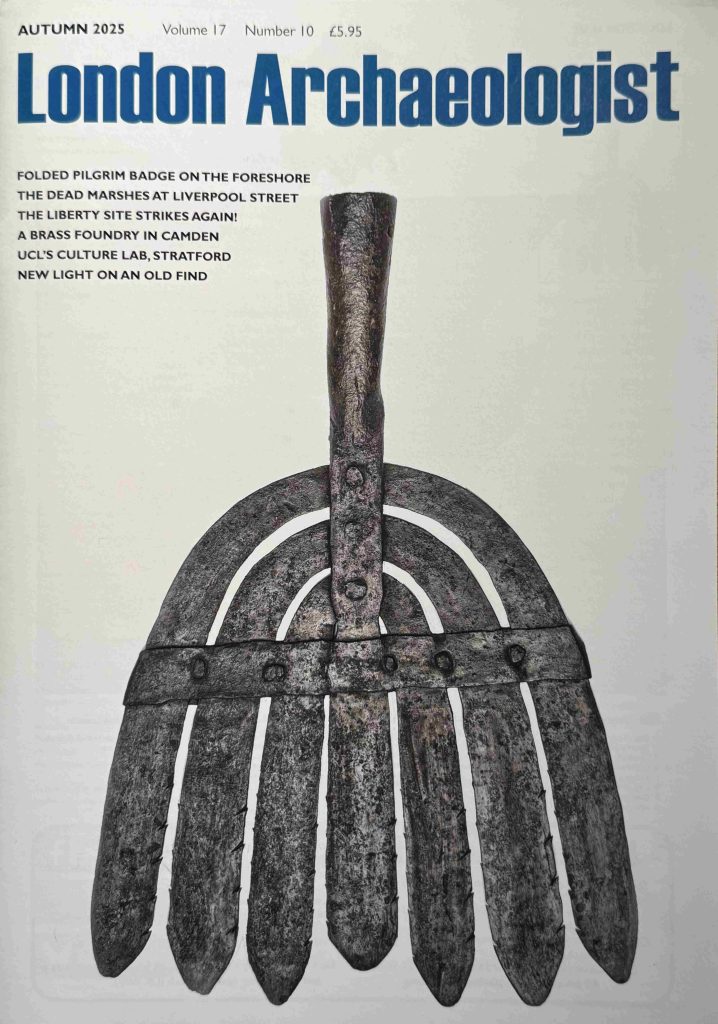

One of the ways of following the work of archaeologists in London, and the latest discoveries is through the publication London Archaeologist, of which the following image is of the latest issue of the four times a year publication:

The cover image is of an iron eel spear, and to give an idea of the type of contents, the autumn edition features excavations at 14-19 Tottenham Mews in Camden as well as excavations at 1 Liverpool Street which has the title “The Dead Marshes” to highlight the historic location of the place.

These two articles are detailed, for example the Liverpool Street report runs to seven pages of text, maps, site plans and photos.

There are also articles about previous finds such as a Roman cremation found on the Old Kent Road, along with the results of new research on the large quantity of Roman painted wall plaster found at the Liberty excavation in Southwark.

A subscription to London Archaeologist is a great way to keep up to date with excavations and general archaeology across the city. The current price of an annual subscription is £22, and details can be found at the following website:

https://www.londonarchaeologist.org.uk

A brilliant thing about the publication is that if you want plenty of reading to explore archaeology across London, then back issues of the publication from issue 1 in 1968, through to the end of 2023 are all available for free, and to download at the Archaeology Data Service, and as an example of the early content available, there is a fascinating article in issue 1 in 1968 on the Roman House and Bath at Billingsgate by Peter Marsden.

The archive provides more than enough fascinating reading for the dark winter evenings, but there is far more to the:

Archaeology Data Service

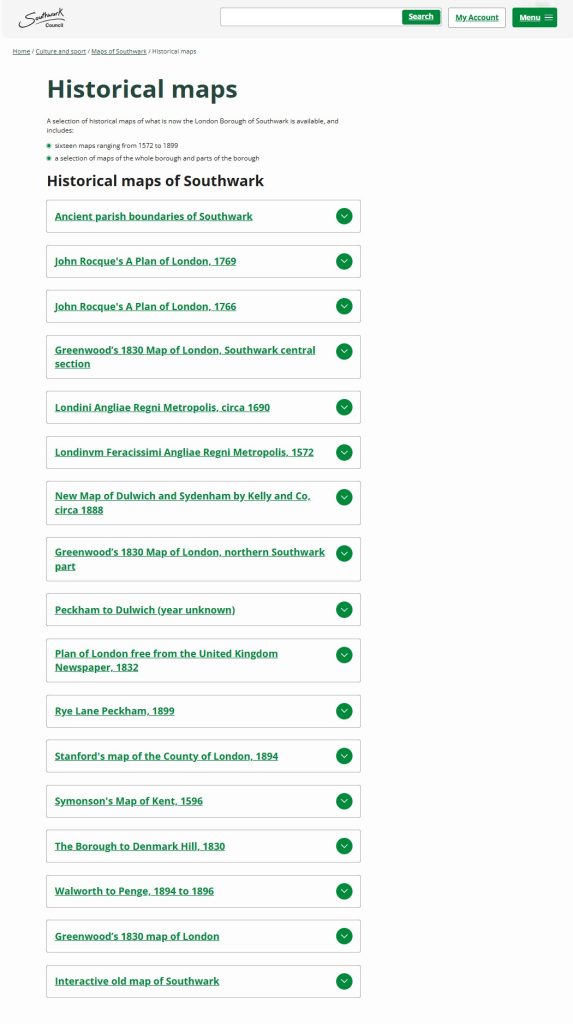

Firstly, the link to the archive of London Archaeologist at the Archaeology Data Service is here:

https://archaeologydataservice.ac.uk/library/browse/series.xhtml?recordId=1000237

The Archaeology Data Service (ADS) is the “leading accredited digital repository for archaeology and heritage data generated by UK-based fieldwork and research”, and it is apparently the oldest repository for archaeology and heritage data in the world, having been established in 1996.

The search methods to explore the database takes some practice, and getting some experience with how to frame queries, but if you are interested in the huge amount of archaeology and heritage across London (and the rest of the country), it is well worth the effort.

The homepage of the ADS is here:

and at the top of the page there are a number of menu options, but to provide an idea of the breadth and depth of contents, I will click on the Search option, where you can then search the Data Catalogue or the Library.

The Library is a database of archaeological investigations and consists of either a summary of a record held in another archive, or a downloadable report (click on “Available from ADS” on Access Type on the left column of options to select records where the reports are available).

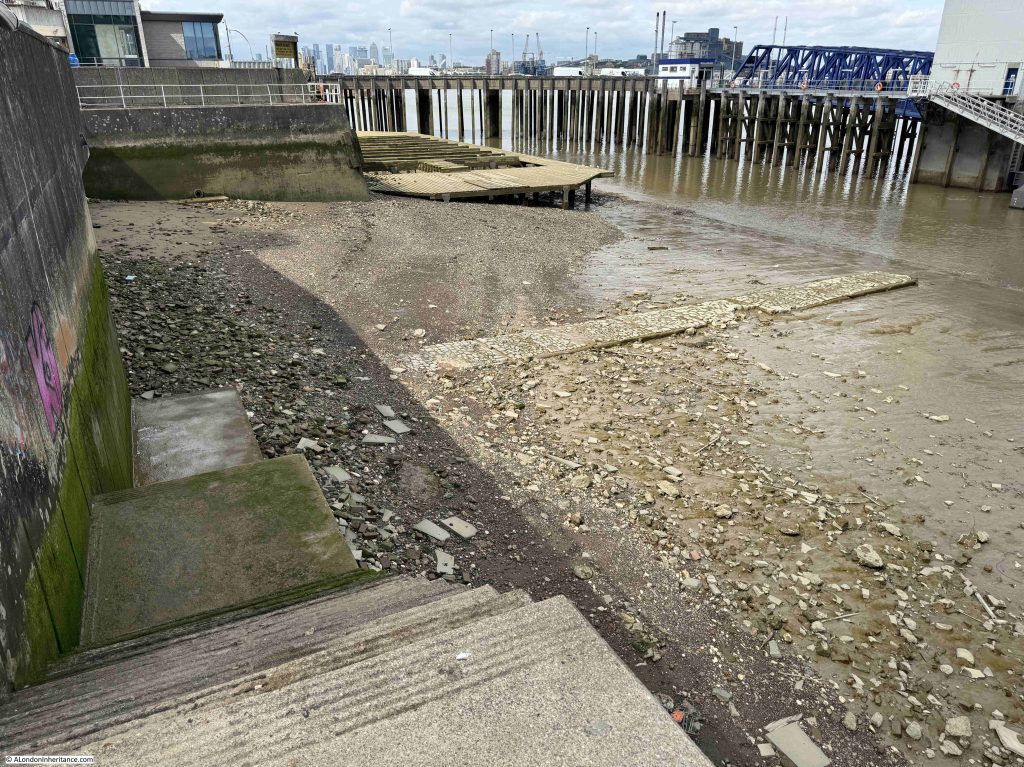

As an example, searching the Library for “Wapping”, there are a number of records, many are a brief abstract, but there are a number with a full, downloadable report.

One of the records is titled, and includes a PDF download of the full report “LAND AT THE HIGHWAY, WAPPING LANE, PENNINGTON STREET AND CHIGWELL HILL, (PARCEL 4) LONDON E1

AN ARCHAEOLOGICAL ASSESSMENT”.

This plot of land is unusual in Wapping in that it is still empty and surrounded by hoardings. It is between Tobacco Dock and The Highway, and is adjacent to the derelict Rose public house (if you have been on my Wapping walk, we walked past the site towards the end of the walk, heading up from Tobacco Dock to The Highway).

The document is a detailed, 524 page report on excavations at the site, including full background detail such as the geology and topography through to a large listing of all the finds.

The location of the empty and derelict land in Wapping (© OpenStreetMap contributors):

Back at the Search Data page, clicking on Data Catalogue brings up another screen, and at top left you will see “Filters” with below this a search box.

Searches can be detailed and specific, but just enter “Wapping” and on the right a whole range of search results are listed, 188 in total (although be careful as there are a number of other Wappings around the country, hence the need to explore how to make specific searches).

The first record covers: “An English cargo vessel which stranded near Flamborough Head in 1891 in fog”, nothing to do with London you might think, but clicking on the Resource Landing Page provides more details from the source, and the “Wapping” was a steam collier that carried coal to London and was known as an “up-river” or “flatiron” due to her low superstructure and with masts that could be lowered allowing the ship to pass under the many bridges of the Thames.

Interesting that a ship that carried coal along the east coast was also able to travel far up the Thames to deliver its cargo, including passing under bridges.

I have been tracing the remains of Civil War defences in Wapping, and a quick search for “Wapping Fort” found the following:

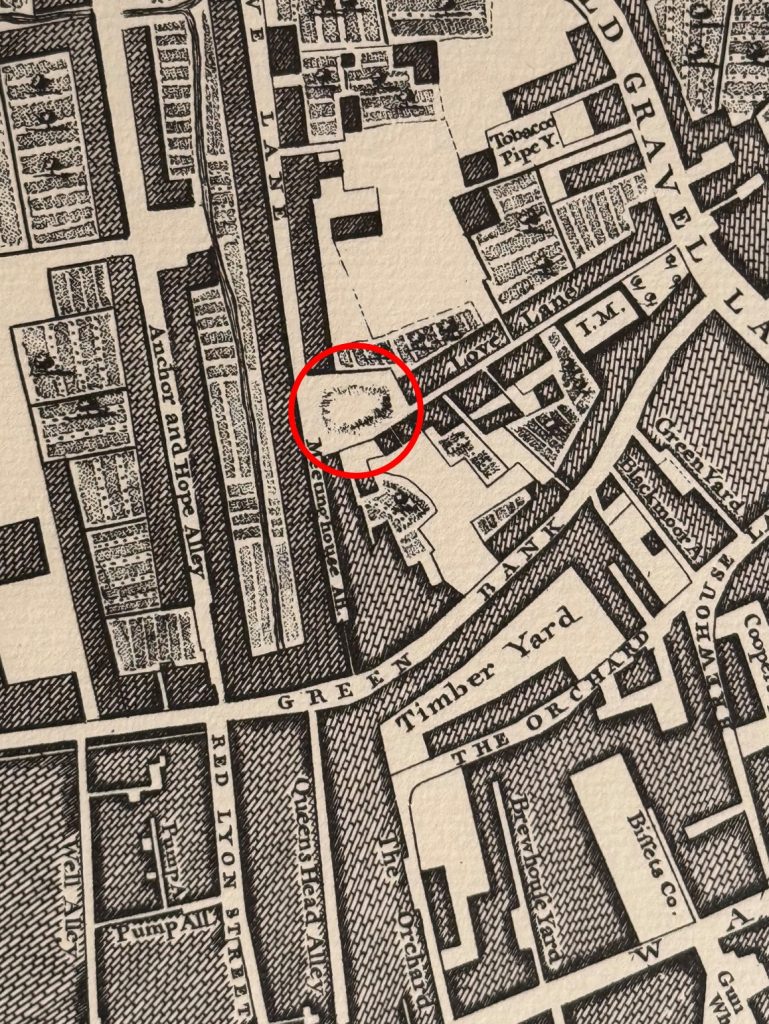

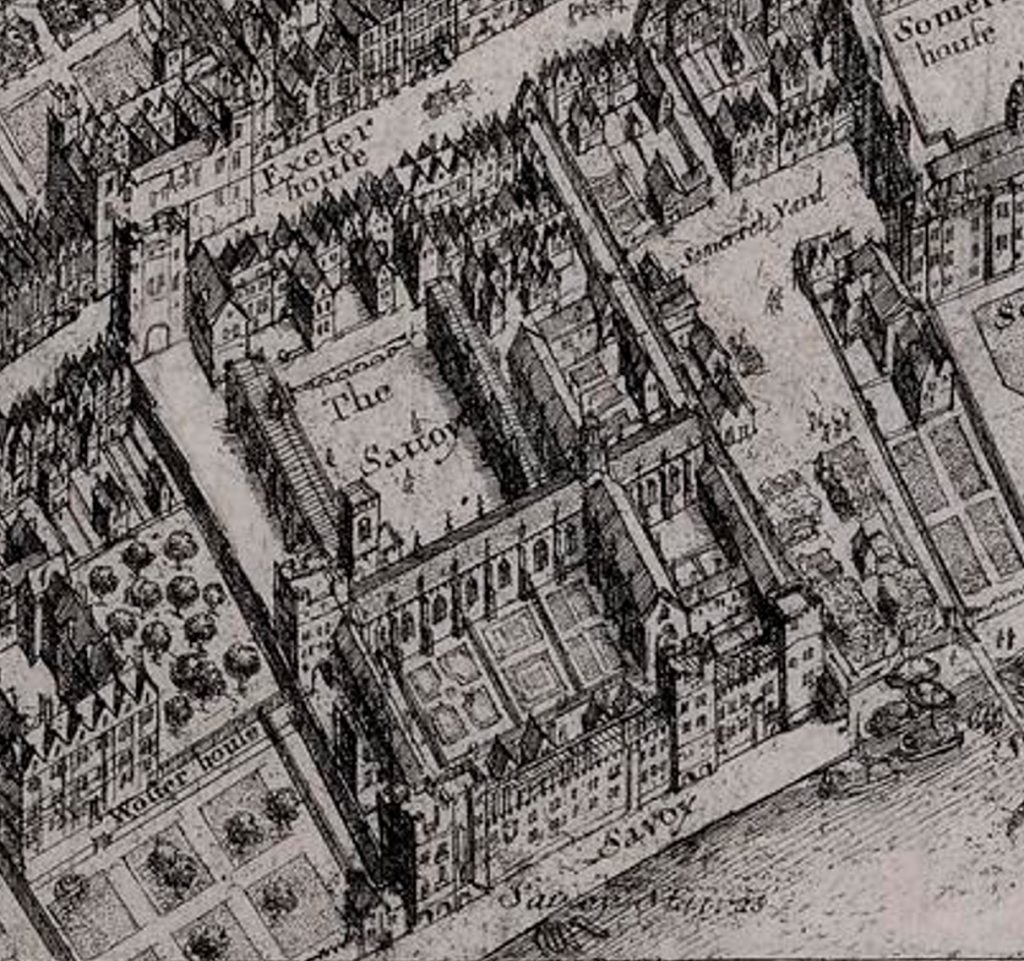

“Fort Number 1 of London’s Civil War defences was in Wapping, south of the Church of St Georges-in-the-East. The common Council resolution called for a bulwark and a half, with a battery at the north end of Gravel Lane, which is where Vertue showed it. Lithgow however refers to it as a seven-angled fort close by the houses and the River Thames Rocque’s map shows a mound on the generally accepted line of the ramparts at the junction of the present Watts Street and Reardon Streets, which would accord more with Lithgow’s location. Lithgow’s description is of a palisaded earth fort having 9 portholes with guns for each.”

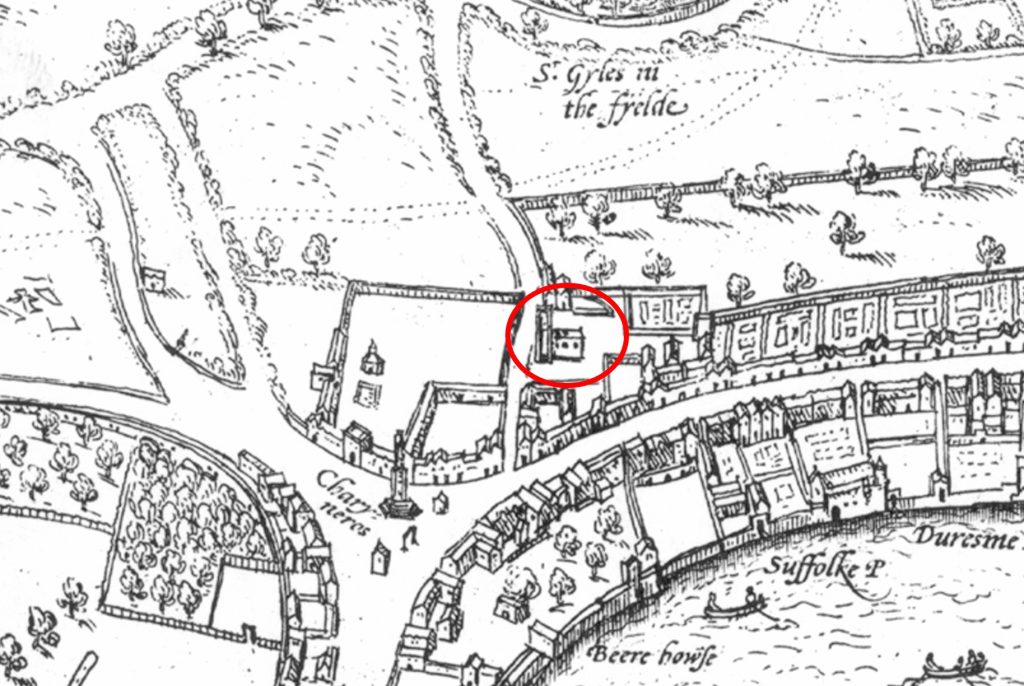

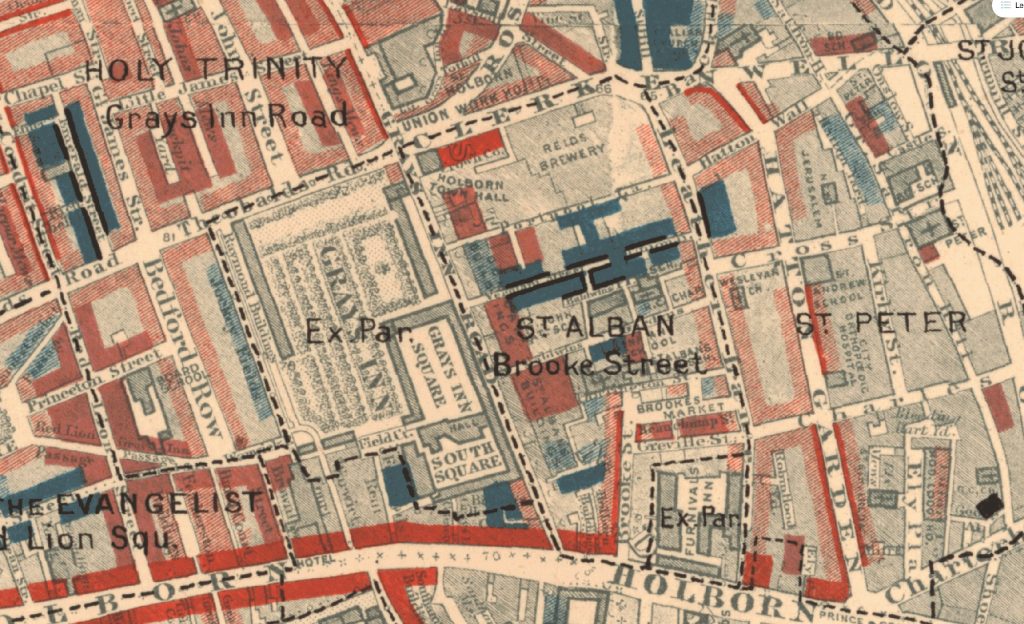

If we look at Rocque’s map, then we can see the mound quoted in the above reference to the Civil War fort in Wapping:

Which is roughly within the red circle in the map of the area today (© OpenStreetMap contributors):

Many of the records returned after a search do not contain details about the site, but can be a brief abstract and / or records of where the information can be found, however there is still plenty to be discovered, and the availability of the London Archaeologist archive at the ADS is a wonderful resource in its own right.

Where there is information in the ADS, such as the detailed reports on excavations, the potential location of a Civil War fort in Wapping, or the collier of the same name that had been designed to carry coals down the east coast, then through to central London, it all helps provide a greater understanding of the city.