The main aim of this blog is to trace the location of my father’s photos of London. He also took many photos across the country whilst out cycling between youth hostels in the late 1940s and early 1950s and I occasionally take a trip out of London to explore the location of these photos. For this week’s post I find the Chichester Market Cross, a link with London and the first fatal railway accident.

This is the Chichester Market Cross photographed in 1949.

The same view of Chichester Market Cross, 69 years later in 2018.

Market crosses were mainly built during the medieval period and often formed a hub for a market, with the Cross providing a location where transactions could be formerly validated. They also served other functions in the daily life of a town, for example as a central point for meetings, preaching, proclamation through both verbal announcements and the use of posters.

They came in many forms, from a basic cross through to the highly ornate structure that forms Chichester Market Cross. The complexity of the design was usually down to the level of funding available and the importance of the primary sponsor.

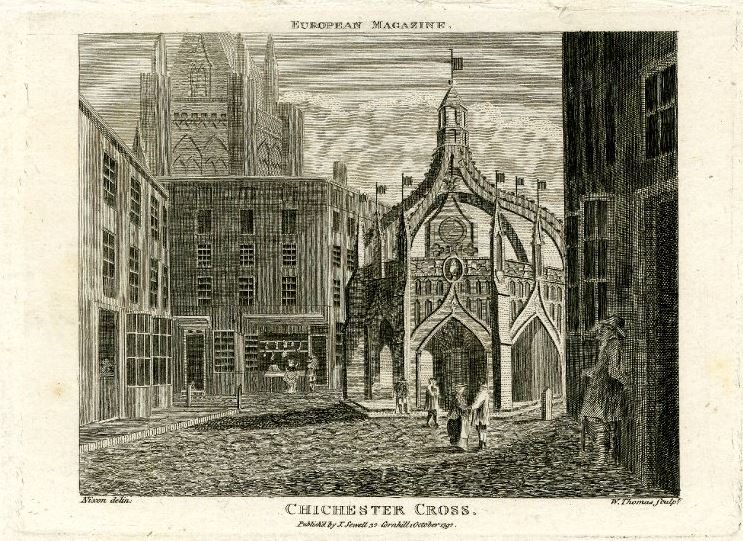

A view of the Chichester Market Cross in 1797 (©Trustees of the British Museum).

The Chichester Market Cross was constructed in 1501 and was funded by Bishop Edward Story who allowed the poorer residents of the town to trade basic goods without payment of a toll, provided they did so within the confines of the market cross.

The stone market cross we see today is not the first, it replaced a wooden structure that dated from the 14th century.

The market cross is much the same as when first built, however there has been damage to the decoration of the cross over the years, particularly during the Civil War. The market cross has been repaired over the years and in 1724 a belfry and clocks were added so the market provided a central reference for the time.

The Chichester Market Cross is Grade I listed, and the English Heritage listing states that the cross is believed to have originally stood in a large market place, rather than the small space within the town centre of today. Over the centuries, surrounding buildings have gradually encroached on the structure and taken up space allocated to the market, particularly after 1808 when the market moved location to find a larger space to serve the growing town.

The central location of the market cross is indicated by the names of the fours streets that radiate out from the market cross. They are North, East, South and West Streets with Chichester market cross sitting in the centre of a compass laid out in the streets.

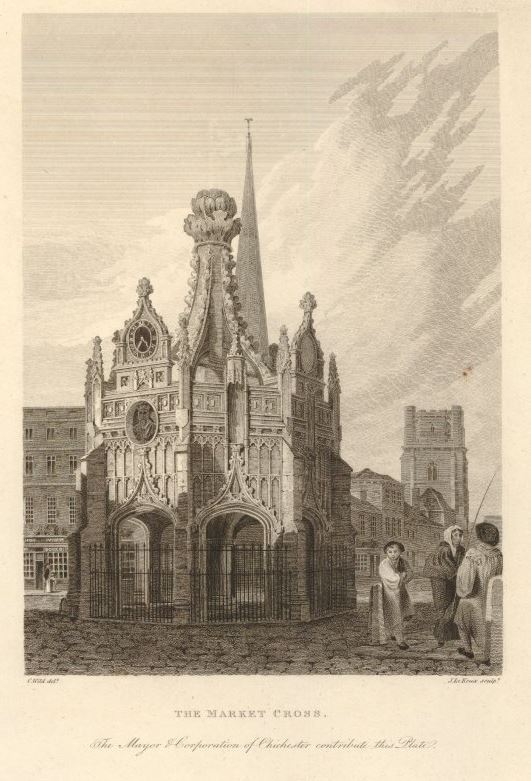

Another drawing of the market cross, with the spire of Chichester Cathedral in the background (©Trustees of the British Museum).

Chichester Cathedral is a magnificent building. It is believed to be built on an earlier Saxon church dedicated to St. Peter. Construction of the cathedral was down to a decree by the Council of London in 1075 that seats of Bishops should be in towns rather than villages. The local bishopric was based in the village of Selsey so in the early 12th century the construction of the new cathedral building commenced.

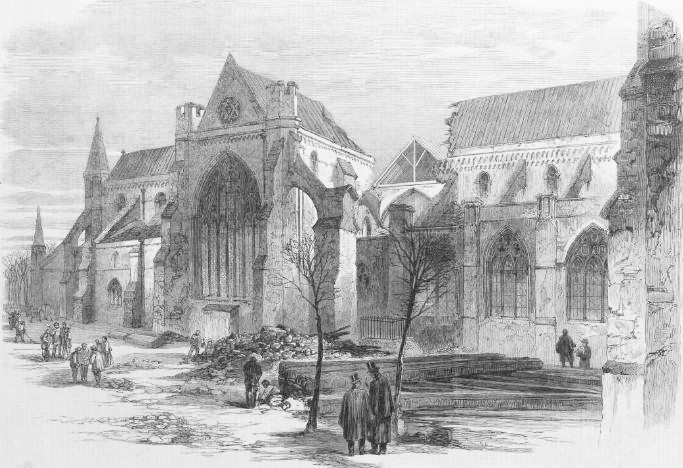

The majority of construction was completed by the early 15th century when around this time the spire was completed. Over the centuries the building has been through numerous renovations, additions and changes. Fires during the first centuries when construction was ongoing, and severe damage to the internal decoration during the Civil War, however the most significant event occurred in 1861 when the original central tower and spire collapsed.

Cracks had been observed in the piers supporting the tower and spire in the months preceding the collapse, and the Illustrated London News of the 2nd March 1861 recorded the events that led up to the collapse:

“After the usual Sunday services in the nave, which had been temporarily screened off, the church was taken possession of by workmen, who have, with but little intermission, pursued their task by night and day down to the hour of the final catastrophe. It soon became evident that the heart or core of the piers was rotten; the task of sustaining a weight on each pier exceeding 1400 tons thrust forward the facing on every side, and when the masonry was restrained in one place by props and shores the restraint caused it to bulge on the adjoining surfaces faster than it was possible to apply remedies. The terrific storm of wind on Wednesday night caused these difficulties to increase with alarming rapidity; but the efforts of sixty workmen appeared still to offer some possibility of ultimate success when, at three hours and a half past midnight they quitted the building.

On their return however, after less than three hours’ absence, it was found that the shores and braces exhibited many signs of suffering from the enormous strains to which they had been subjected. The force of men was increased, and various expedients to strengthen what was strained were put into requisition. The crushing and settlement of the south-west pier poured out, crushed to powder, and the workmen were cleared out of the building, and the noble spire left to its fate. Not more than a quarter of an hour later the tower and spire fell to the floor with but little noise, forming a mass of near 6,000 tons of ruin in the centre of the church, and carrying with it about 29ft in the length of the end of the nave, and the same of the transepts and choir.

The spire in its fall, at first inclined slightly to the south-west, and then sank gently into the centre of the building. The appearance of the fall has been compared to that of a large ship quietly but rapidly foundering at sea.”

The Illustrated London News quickly dispatched one of their artists to draw the following print of the collapsed tower and spire, and the severe damage to the building.

The spire was quickly rebuilt in 1866 by Sir George Gilbert Scott and reaches the height of 82 metres.

Entrance to Chichester Cathedral:

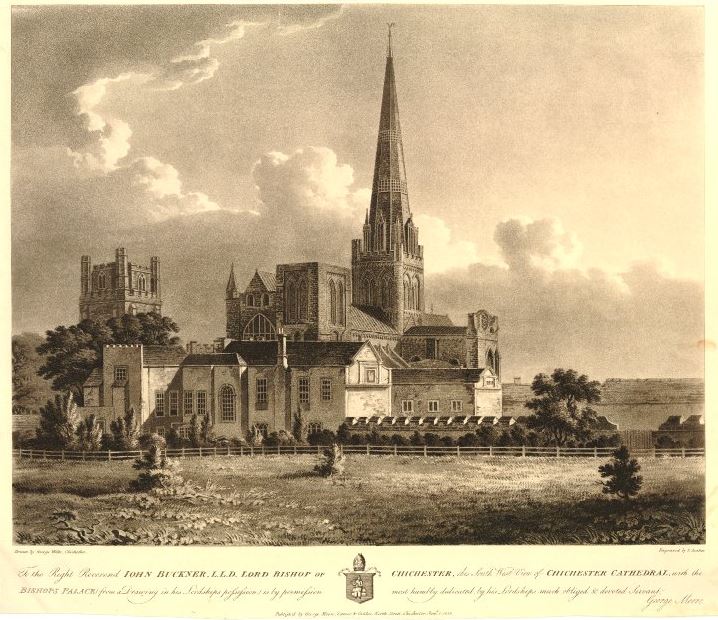

Surrounding buildings makes it difficult to get a good view of the cathedral, however this view from 1812 provides a good impression and shows the original tower and spire, confirming that the later 19th century rebuild is very similar to the original (©Trustees of the British Museum).

Chichester Cathedral is unusual for the location of the bells. In the above drawing, there is a large tower to the left of the cathedral building. This is the separate bell tower:

There is no firm date for the construction of the tower, however it appears to date from the early 15th century. There is no written explanation from the time as to why a separate bell tower was needed. One theory appears to be concerns that vibrations from the bells in the main tower could have caused damage to the tower and steeple, therefore a separate tower was constructed to house the bells.

Time to visit the interior of the cathedral. The view along the nave to the main entrance.

The screen separating the nave from the choir.

The choir.

As could be expected in a church of this age, numerous monuments, tombs, carvings and artworks can be found around the church.

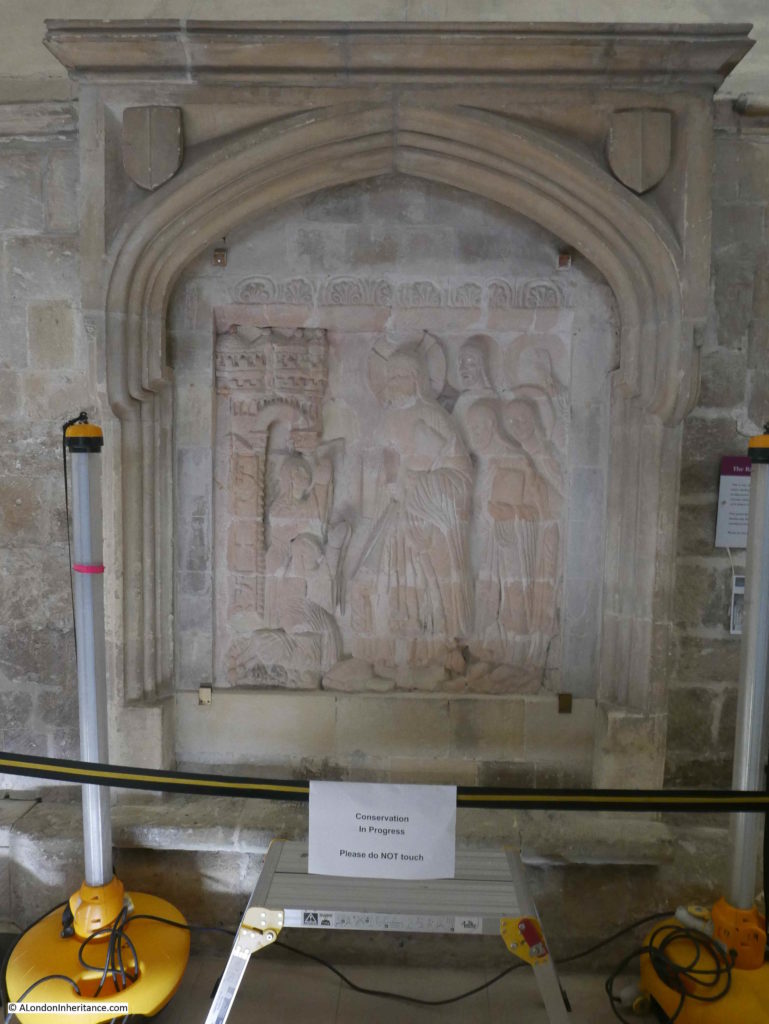

This is one of two carved panels, currently under restoration, depicting the raising of Lazarus. Dating from around 1125, they were concealed for many centuries, only being rediscovered in 1820 and installed in their current location.

There is one historical display that personally, I found the most interesting in its dimensional representation of layered buildings and time. Set into the floor is a clear panel with the interior space brilliantly lit.

Peer below the surface of the floor to find part of a Roman mosaic.

An adjacent information panel informs that this is a section of a second century mosaic belonging to part of a large Roman building that extended under the cathedral wall. Remains of part of the Roman city of Noviomagnus which lies about a metre below the surface of modern Chichester.

It is a brilliant way to display the mosaic. It demonstrates the physical layers of history in that the Roman city is below the current cathedral floor, as well as the layers of time, standing in the 21st century on the floor of a cathedral started in the 12th century, looking at the remains of a building from the 2nd century – it gets the imagination going.

There are many tombs around the cathedral, including that of Joan de Vere, daughter of Robert, Earl of Oxford who died in 1293.

In the south transept are a series of paintings on wood from the 16th century by Lambert Barnard, court painter to the Bishop of Chichester.

This is the Arundel Tomb with the figures of Richard Fitzalan, the 3rd Earl of Arundel and his second wife Eleanor “who by his will of 1375 were to be buried together without pomp in the chapter house of Lewes priory“. After the dissolution the tomb, along with some others now in Chichester, were moved from Lewes into the cathedral.

To understand one of the unique aspects of the Arundel Tomb, you need to look at the detail of the two figures:

The legs of Eleanor appear crossed and turning towards her husband. The right hand of Richard is across to Eleanor and they are holding hands. A sign close by the tomb informs that the hand holding was originally though to have been due to 19th century restoration, but recent research has confirmed that it is original.

This display of affection by a knight is highly unusual for the 14th century.

Close by there is a monument from several centuries later. This is the monument to William Huskisson.

The text underneath the statue provides some background:

“To the memory of William Huskisson, for ten years one of the representatives of this city in Parliament. This station he relinquished in 1823. When yielding to a sense of public duty he accepted the offer of being returned for Liverpool for which he was selected on account of the zeal and intelligence displayed by him in advancing the commercial prosperity of the empire. His death was occasioned by an accident near that town on the 15th of September 1830, and changed a scene of triumphant rejoicing into one of general mourning. At the urgent solicitation of his constituents he was interred in the cemetery there amid the unaffected sorrow of all classes of people.”

William Huskisson has the unfortunate distinction of being the first fatality from a railway accident in Great Britain. The following extract from “The Face of London” by Harold Clunn explains:

“Huskisson was killed by a locomotive at the ceremonial opening of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway on 15 September 1830. The procession of trains had left Liverpool, and at Parkside, the engines stopped for water. Contrary to instructions, the travellers left the carriages and stood upon the permanent way. Huskisson wanted to speak to the Duke of Wellington, and at that moment several engines were seen approaching along the rails between which he was standing. Everybody else made for the carriages, but Huskisson, who was slightly lame, fell back on the rails in front of the locomotive Dart, which ran over his leg; he was carried to hospital, where he died the same evening.”

The London connection is that there is also a statue of William Huskisson in Pimlico Gardens. The following photo is from my post on the area and shows Huskisson in a very similar style, looking more like a Roman senator than an English MP.

There must be a Roman theme as a statue of Huskisson was also commissioned for display in Liverpool. The following drawing from the Illustrated London News shows the Liverpool statue looking very similar to those in Pimlico and Chichester.

The text with the drawing provides a possible explanation in that the Liverpool statue was cast in Holland from a statue executed in Rome by Gibson (John Gibson, the sculptor born in Wales in 1790, and who provided works of the Duke of Devonshire and a statue of Queen Victoria for Buckingham Palace). So poor old Huskisson has ended up in all his public sculpture looking like a Roman Senator, although I suspect he will always be known as the victim of the first, fatal railway accident.

The interior of Chichester Cathedral is magnificent, however there is more to explore outside as the cathedral has extensive grounds surrounding the building.

Firstly a wonderful set of cloisters, walled on one side and perpendicular windows on the opposite side.

Alleys and lanes thread their way through the buildings in the cathedral grounds, and provide wonderful glimpses of the cathedral. This is St. Richard’s Walk. Hard to imagine the sight described in the Illustrated London News of the collapse of the tower and spire.

Canon Lane runs roughly east to west along the southern edge of the cathedral grounds. At each end of Canon Lane there is a substantial gatehouse.

This is the gatehouse leading from Canon Lane into South Street, one of the four main streets radiating out from the market cross.

The gatehouse as seen from South Street,

Chichester market cross is another of my father’s photos I can tick off, but by going to these locations they provide the perfect opportunity to explore the wider area and Chichester is a fantastic place to explore and I have only touched on the cross and cathedral.

The Roman mosaic on display beneath the floor of the cathedral was for me, the most fascinating. Seeing this type of feature always heightens my awareness that we are walking on layers of history and time. Southwark Cathedral has a very similar feature, as does All Hallows by the Tower.

I was told that Roman garb was ùsed by sculptors in past times to indicate statesman-like qualities. Pitt the Elder’s statue in the Guilhall is similarly dressed.

Another very interesting and well researched article. A really great series of work. Please keep it up.

Couple of points that might be of interest:

The effigy of earl of arundel and his wife is indeed very touching. The unusual depiction for the time has been the subject of much commentary including most famously a beautiful poem by Philip Larkin ” An Arundel Tomb”. As with most of Larkin’s work, well worth reading.

Depiction of famous figures as ancient Roman senators was quite common from the Rennaisance on ( see for example the statue of Dr Johnson in St Pauls Cathedral). Part of that great respect past generations had for the classical world.

Now the study of classics is no longer universal, depiction of relatively modern figures as roman senators looks more incongruous I guess.

Went there this summer while escorting the Father in Law on his annual holiday. Chichester Cathedral is bang up to date with a contactless donation machine.

I’ve never been to Chichester but learnt a lot from your blog. Thanks.

I read that Chichester Cathedral is the only English medieval cathedral that was visible from the sea. Presumably it didn’t pay to advertise your wealth to coastal pirates, whether Saxon or Viking. An example was Lindisfarne Priory which lost its prominence to Durham as a result.

The geology of much of the south of England is not very conducive to the construction of heavy buildings. Winchester Cathedral had enormous problems in its construction. A separate bell tower carrying very heavy metalwork could be buttressed more effectively. It didn’t work very well at Pisa though!

Always read your posts even if I don’t comment normally. But always appreciated. Thank you.

I think I can add something about the Market Cross. Local firms of solicitors realised that a lot of their correspondence was with each other so every morning at an appointed time representatives of each firm met under the Market Cross to exchange letters. This had been going on for many years when in the 1970’s there was a major postal strike. To overcome this and inspired by the example of the routine in Chichester, the idea of a document exchange was taken up commercially. To begin with it involved solicitors mostly, but expanded to other businesses and is still going strong.

Never been convinced that Huskisson was the first railway fatality. Surely some poor anonymous soul in the North East must have fallen victim on the Stockton & Darlington before 1830?

My first thought was that the Roman flooring doesn’t display much imagination. There is Roman tiling of a very similar design on display in St Albans. Presumably these were laid for normal domestic use, rather than meant as works of art.

Must pay a visit soon I used to work in Chichester many years ago I am a lot more knowledgeable thanks to your information, i would like to tie it in with a walk on stane st Roman rd.