Yesterday evening, the 29th December, was the anniversary of one of the most intensive bombing attacks on London, when on the 29th December 1940 a mix of high explosive and large numbers of incendiary bombs created significant destruction across the City. It was during this raid that the image of the dome of St. Paul’s Cathedral, rising above the smoke and flames of the surrounding destruction was symbolic of both the suffering of the City and the will to survive.

I have written about the raid in a couple of previous posts including The Second Great Fire of London and the St. Paul’s Watch, and for this week’s post I would like to bring you another perspective from the same night.

Of the many buildings that surrounded the Cathedral to the north along St. Paul’s Churchyard and Paternoster Row were the offices, factory and warehouses of Hitchcock, Williams & Co. I am not sure how best to describe the company, but at the time they were a form of Fashion House and drapery, manufacturing and selling a wide range of clothes, hats, fabrics, ribbons etc.

The firm was established in 1835 by George Hitchcock and a Mr Rogers, who would leave in 1843. George Williams who originally joined the company as an apprentice, became a Director with Hitchcock in 1853 when the partnership Hitchcock, Williams & Co was formed. Always based in St. Paul’s Churchyard, firstly at number 1, then at number 72, with the firm expanding to take in many of the surrounding buildings.

George Williams originally joined the business as an apprentice, and as well as becoming a partner with Hitchcock, received a knighthood from Queen Victoria for services, which included the inauguration of the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA) which was founded in a room of the company’s premises in St. Paul’s Churchyard.

The buildings of Hitchcock, Williams & Co. were destroyed during the raids of the 29th December 1940. A paragraph in the newspaper reports of the raid included a mention of the company:

“The historic room in which the Young Men’s Christian Association was started was among the places destroyed on Sunday night. With seven other buildings, the George Williams Room – named after the founder, the late Sir George Williams – was burned to ashes. It was situated in the premises of Messrs. Hitchcock, Williams and Co, manufacturers, warehousemen and shippers, of St. Paul’s Churchyard, and was originally one of the bedrooms used by the 140 assistants employed in the Hitchcock drapery business.”

Just after the war, a small book was published by the Company, titled “Operation Textiles – A City Warehouse in War-time”, written by H.A. Walden, an employee of the company.

It is a fascinating book and provides not just a detailed account of an individual business in the City of London, but also as being written at the time, by an employee, provides a view of how a typical City company operated.

The book includes a number of photos which show daily life in the company before the war, during preparations for war and the results of the raid of the 29th December.

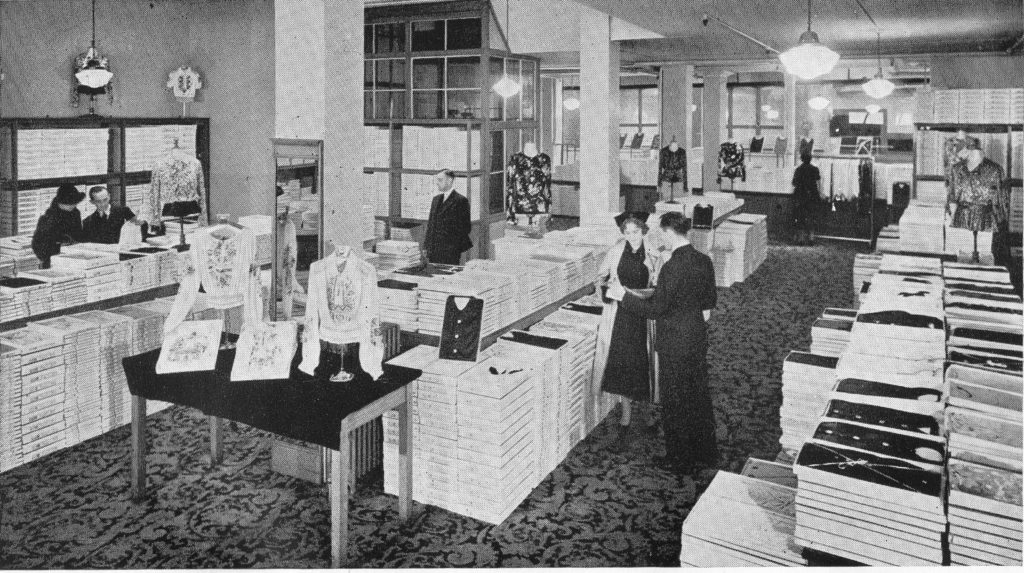

The following photo is titled “A Pre-Blitz View of our Blouse Department”:

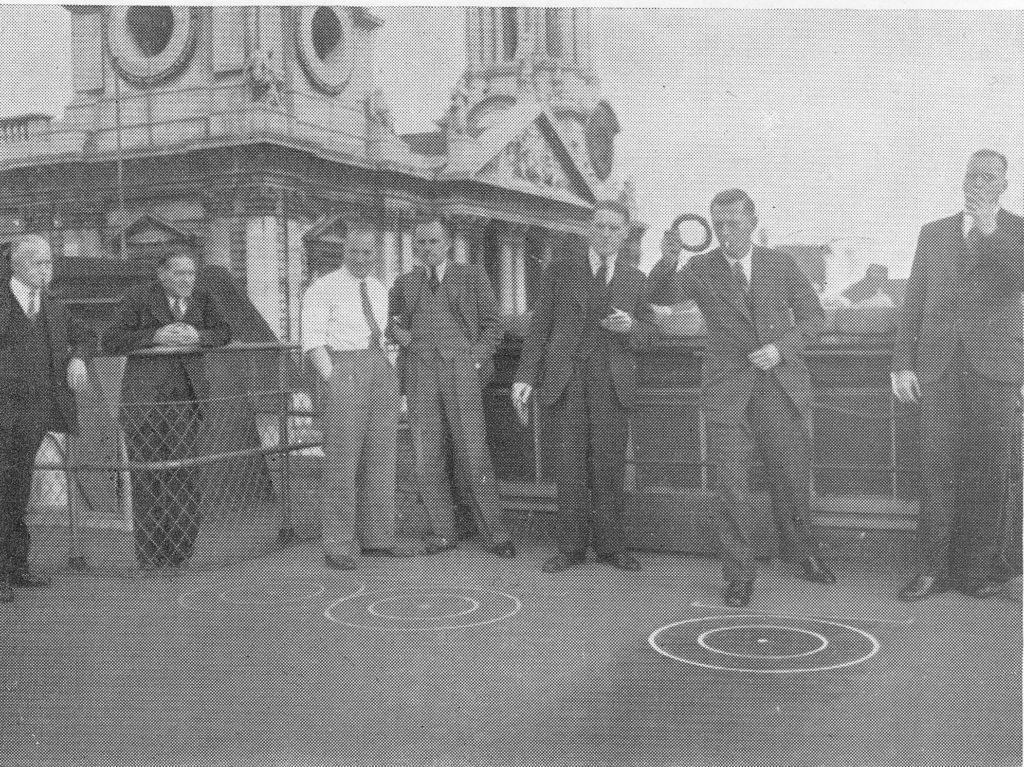

“Staff Quoit Competition” – This photo helps show exactly where the Hitchcock, Williams building was located with the main entrance to St. Paul’s Cathedral, facing Ludgate Hill, seen in the background.

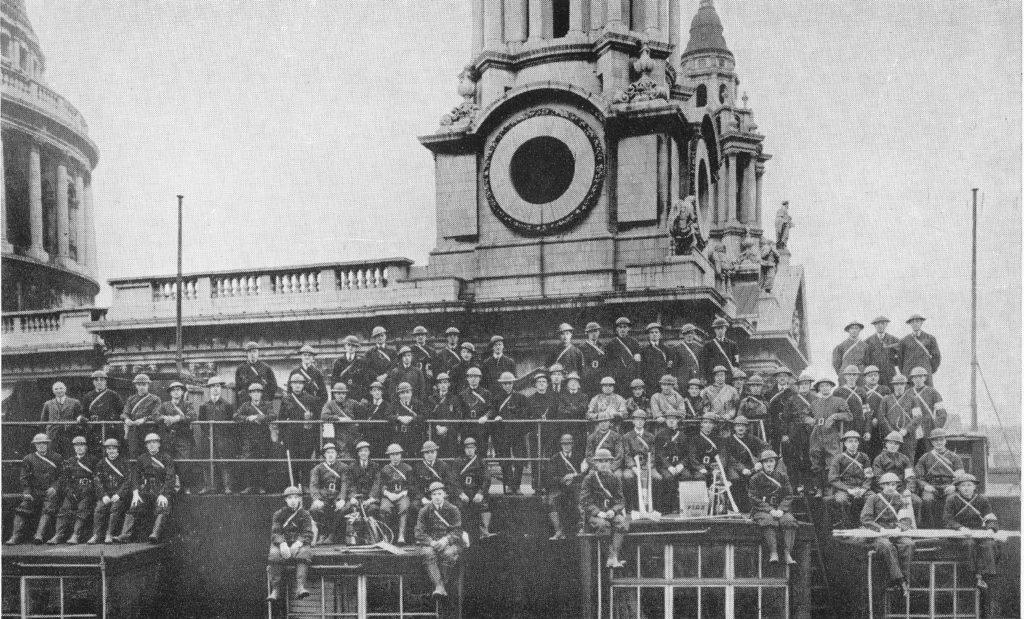

In fact St. Paul’s Cathedral features in the background of many of the photos in the book. The following photo taken in 1940 is titled “Our Firefighting And First Aid Units”:

In the following view of St. Paul’s Churchyard today, the buildings of Hitchcock Williams & Co occupied the majority of the space now occupied by the buildings, starting with the brick faced building on the right, where the old Temple Bar now stands and the majority of the space occupied by the taller building curving from right to left.

In the early stages of the war, building owners were encouraged to form their own fire fighting teams, and many City buildings were manned by employees of the company to help defend the building from what was expected to be attacks from explosive and incendiary bombs, although they were mainly equipped with buckets of sand and stirrup pumps, which were to prove of limited use on the night of the 29th December.

Preparations for war included not just the formation of fire fighting and first aid teams, but also protecting the building with sandbags as this photo titled “Sand Shifting Volunteers” demonstrates:

This photo titled “Stand Easy” shows part of a roof apparently lined with sandbags.

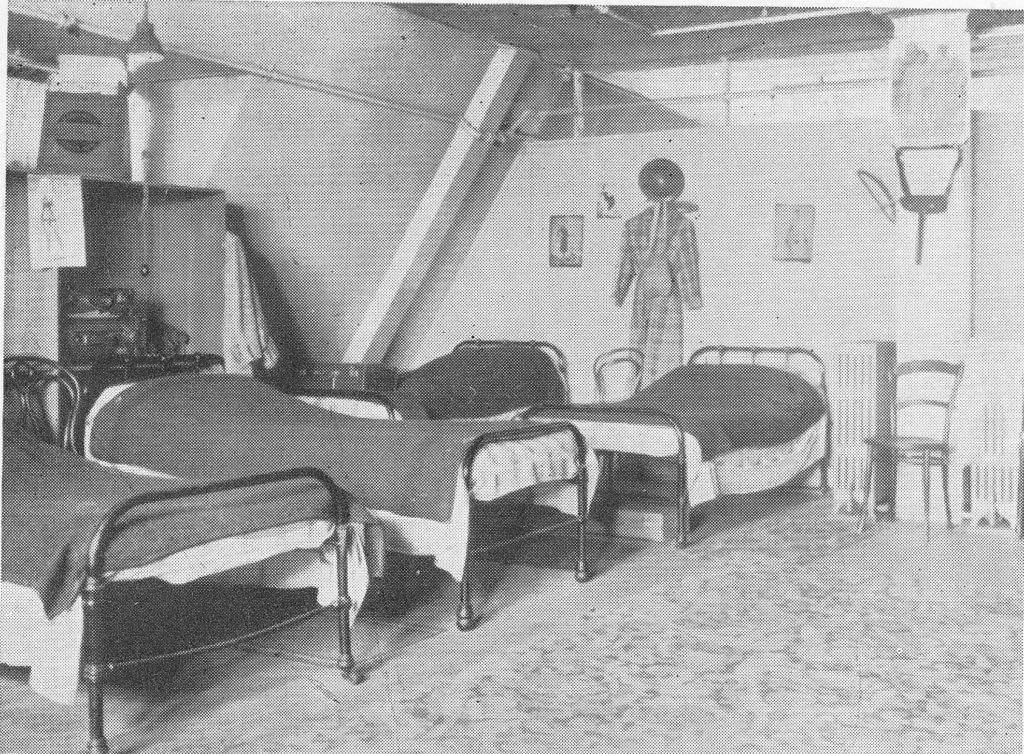

Hitchcock Williams & Co, as practiced by other large City companies, had a number of residential employees and during the war preparations included converting rooms to overnight shelters for residential staff and those assigned to fire watching shifts. This photo titled “Squeezin Hotel Bedroom” shows one of the converted rooms.

Judging by the preparations and planning detailed in the book, Hitchcock Williams & Co. was probably as well prepared as any City company at the start of the war, however such was the intensity of the raid on the 29th December 1940 that even with incredibly dedicated staff and detailed planning and preparations, they were insufficient to save the buildings in St. Paul’s Churchyard.

Rather than precis the events described in the chapter of the book that covers the 29th December, the following are the words written by H,A. Walden who was there on the night. The chapter has the perhaps rather understated title:

“The Great City Fire Blitz And How It Affected Our Personnel And Premises”

“It has been said, and written, that not since the Great Fire of 1666 has there been such a conflagration in the City of London as occurred on Sunday night, December 29th, 1940, the result of Nazi incendiary bombs. In this ‘blitzkrieg’ whole areas of the City became smoking ruins within a few hours. Narrow thoroughfares, old familiar places and historic landmarks, were obliterated. To write adequately of the scenes of destruction seems beyond the limit of one’s descriptive powers.

It was an awe-inspiring sight for those of us who witnessed it. St. Paul’s Cathedral, ringed by raging fires and falling masonry, its great dome superimposed and reddened all night by the reflected flames, seemed to take upon itself an even greater dignity, as it stood in the midst of this example of ‘Man’s inhumanity to man.’

Approaching the City from the South, I saw by the lurid sky that the fires must be near the Cathedral, and felt apprehension about our own premises. The journey on foot along Cannon Street, deserted but for firemen, was of a nightmare variety. Several big fires were in progress, particularly a large Queen Victoria Street block, the smoke and sparks of which filled the air. the sound of hostile planes roaring overhead and the hiss of great numbers of falling incendiary bombs, seemed more menacing than usual. Taking cover in various doorways en route, and reaching the Cathedral, I found that our near neighbours, Debenham and Company’s premises were almost gutted and Pawsons and Leaf’s roof alight in several places. The roadway was a mass of fallen masonry, and hose-pipes interlaced towards the brow of Ludgate Hill, where other fires were taking hold. Various buildings in Paternoster Row, Ivy Lane, Warwick Avenue and London House Yard were burning furious, and I shall not forget seeing the faces of some of our fire fighters in the glare, with every detail defined at a considerable distance. It should have been possible to read clearly by the light of the many fires.

Passing into the Warehouse, I learned that hundreds of firebombs had fallen in the near vicinity, some even on the Cathedral. Those which fell on our roof were effectively dealt with by our own squads, some of whom went out into the street to extinguish other incendiaries.

Here it must be recorded that many fires might have been avoided if other Warehouses and buildings nearby had had organised watchers and fire fighting staffs, such as our own. Perhaps, indeed, our premises would have been spared, for there appears to be little doubt that we became the eventual victims of other negligence, or lack of precaution.

In addition to our own fire fighters and first aid men on duty, there were about 80 other occupants of our basement shelters, comprising assistants of both sexes and domestic staff, most of whom were unaware of the close proximity of the fires or the danger outside. Soon word was received that our premises must be evacuated at once, and Mr. Lester instructed me to conduct the women members of the staff immediately to the Crypt of St. Paul’s , where arrangements had been made to receive them. They quietly collected their necessities and blankets, and with one or two excusable exceptions, the calm manner of their journey despite the sight of flames and sparks which greeted them upon coming out of doors at ground level, is worthy of very special mention. The men followed shortly afterwards. All were most kindly received by Canon and Mrs’ Cockin and other clergymen and helpers. We were given cocoa and made as comfortable as possible on pews and forms. The quiet atmosphere of the Crypt made it seem miles away from the outside world. It was the first visit for some of the staff, and one clergyman was soon answering questions from a young lady regarding the Duke of Wellington’s huge funeral carriage standing nearby. By this time, Wren’s Chapter House adjacent to our own premises, was ablaze, and our old building, 69/70 St. Paul’s Churchyard, despite the firemen’s efforts, had caught fire.

It was a hopeless fight from the start. memories of this old part of the House, with its Victorian outline, came crowding in. How it had witnessed so many of the Cathedral ceremonies! How, in happier days, over many years, it had been made colourful and bedecked with flags and bunting to welcome Royalty and others visiting the City and St. Paul’s, the personalities who had worked there and long since passed on – old friends who used to visit its departments – the present staff which manned them, and their reactions when on the morrow they would come and find the old place a ruin of twisted steel! The quiet, philosophic bearing of Mr. Hugh Williams and the Manager as they stood and watched the burning warehouse were an example to us all.

To define in praise the work of our fire fighters would be to limit the extent of their great service. Three times the Police instructed them to leave as the building was becoming dangerous; but they refused to go, and eventually Mr. Lester had personally to order and almost drag them away. Even then they asked to stay and continue the unequal struggle. Stirrup-pumps were futile weapons to deal with such a fire. many of our men were utterly exhausted when finally they withdrew.

As we feared, there was worse to follow. The flames of burning buildings in narrow Paternoster Row fanned by a strong wind contributed to the succumbing of the newer blocks of our premises, the rear portion of which was soon doomed – steel and concrete have their limitations. The task of the squads of regular and auxiliary firemen was hopeless and overwhelming. Water was at a low pressure because of its universal demand over a wide area. Many of us could neither rest nor remain in the Crypt, but came out at intervals to stand and stare, fascinated – and dejected – at the scene confronting us but a few yards away; we were even warmed by the heat of the blaze. It was eerie to see the hoses lit up by the flames. They resembled giant snakes sprawling across the roadways and pavements. Most of the staff had by now put down their blankets on the stone floor of the Crypt and endeavoured to obtain some sleep. My own blanket covered a flat gravestone, the inscription of which recorded the death in 1787 of Elias Jenkins, a former verger of the Cathedral. It was surprising that so many actually slept, particularly those who were shouldering the great responsibilities and anxieties of the future.

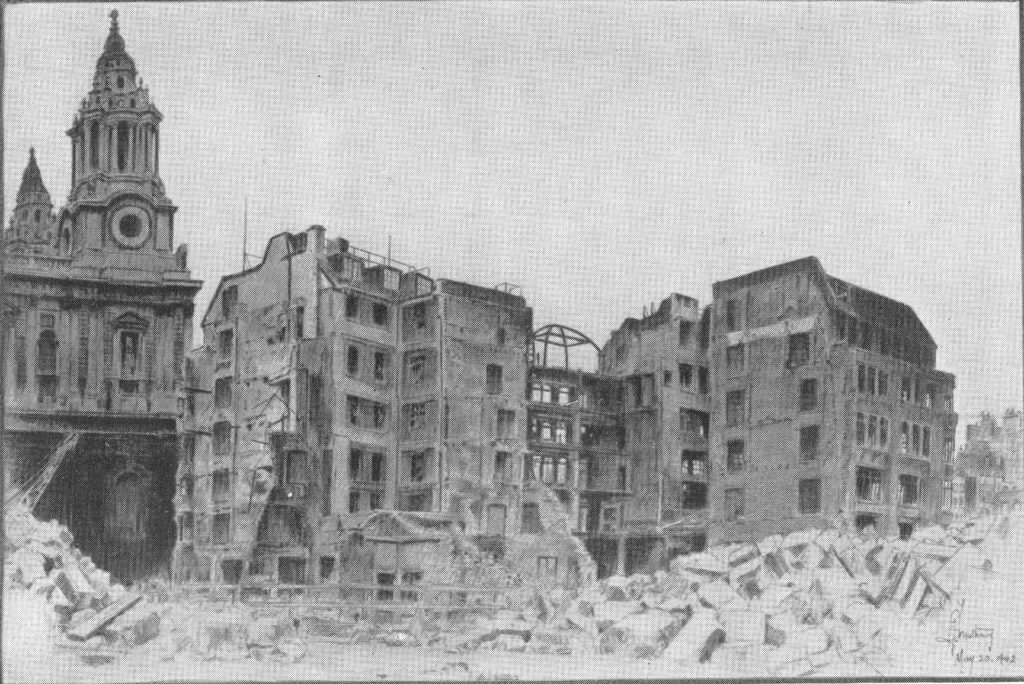

The following photo is titled “Our Old Building, December 29th, 1940”:

On the 29th December 2018 I took the book with me to St. Paul’s Churchyard to track down the location of a couple of the photos. The following photo is of the same view as the above. Part of the Chapter House can be seen on the right of both photos. This is the only building that was rebuilt after the war and remains to this day.

In the grey light of a chaotic dawn, with buildings still ablaze, breakfast was where one could find it. There was very little water, and it was a strange sight to see people walking about with kettles in their hands trying to obtain it. Most of the staff who had been there all night were now sent home. The Headquarters of the Firm were made temporarily at Messrs. Evans’ Restaurants (next to our own premises), which had, apart from water damage, escaped the fire. We record our grateful thanks and admiration of Miss Richards and Miss Sheer, of their staff, who literally took us in and fed us. They made tea and cooked under the most irksome conditions, and were indefatigable in their cheerful assistance. They had slept in our basements for many weeks previously.

Our staff assembled here on Monday morning, seeking advice and instruction. The addresses of all were registered, and, with a few exceptions they were told to return home and await orders. This went on for two or three days, and about a dozen of us occupied the Crypt for a second night. Parts of our building were still burning, and it was late on this second occasion that some of us had the unusual sight of the Dean of St. Paul’s in his shirtsleeves, surveying our premises from the Crypt door. With a smile he remarked, ‘It takes Hitchcock, Williams an awfully long time to burn’.

The Firm had by now sought and found temporary offices at Textile Exchange, in the Churchyard, overlooking our still smoldering premises. The main room of these offices became a meeting place for everyone seeking information or giving it. A small Counting House and Entering Room staff were occupied acknowledging all mail and dealing with inquiries and urgent affairs. Mr Lillycrop had, fortunately, before leaving our stricken building, removed some books containing our customers’ names and addresses, thus enabling us to inform some thousands of them by January 7th of the calamity which had befallen our premises. A great number of replies were received expressing sympathy and offering help in some form or another. These greatly heartened and encouraged the Firm and staff in their determination to carry on. One letter concluded with, ‘Heil Hitchcock’s! Damn Hitler’.

The following photo is titled “Our Paternoster Row Frontage (after December 29th, 1940)”:

The following photo is of roughly the same scene today. The above photo extends further to the right than the photo from today, however that part of the view is obscured by the building on the right.

The following photo is titled “One Of Our Departments After The Fire”:

The following photo is titled “Main Roof Damage”:

The following photo is titled “Our Warehouse After Hitler Passed”:

Many problems were now being dealt with, to give but a few – Where should we find premises to house our Departments? In what state were the hundreds of ledgers and account books in the strong room which had now been submerged in debris and 14 feet of water? Where to obtain new stocks with the ‘Limitation of Supplies Act’ in operation? The claims of many members of staff who had lost their personal possessions in the fire? Where to accommodate the previously ‘living in’ staff, of whom there were approximately 150, when they returned to business? Immediately on seeing the staff on Monday morning, Mr. Hugh Williams, the Manager and some of the buyers went to inspect various places with a view to securing the premises and were able to obtain possession of four warehouses in the West End, and two showrooms in Cannon Street. By January 13th all these premises were in occupation by the various Departments which began establishing stocks and dispatching goods, though handicapped by a complete lack of counter fixtures etc.

The floor space in those early days was but a shadow of our former capacity, and indeed still is.

In addition to the complete loss of our main premises, there were also completely destroyed our four factories and workrooms, maintenance workshops at Warwick Lane and resident quarters at Crown Court, with everything they contained. Only Soft Furnishing and Piece Goods Departments were re-established in the City, at Scott House, Cannon Street, but on May 10th 1941, this building was also totally destroyed by enemy action. These departments were eventually transferred to the rehabilitated first floor of what remained of our 72 St. Paul’s premises.

The problem of the flooded basements containing our strong room and in it all our books and records was a serious one. Pumps were installed and operated for several days before the water was cleared, and debris removed, to allow an examination to be made of the contents. The strong room was found to have been badly flooded, and the removal of sodden books and documents and the process of hand drying every page by our already augmented staff will not soon be forgotten. The drying and de-ciphering continued for many months, in many cases figures became obliterated by mildew setting in. The practical help given by our customers who, when remitting, forwarded copies of their own ledgers was of great assistance to us. Many were themselves in a similar case and the difficulties of reconciliation of indebtedness can be appreciated. One customer at Hull had his premises destroyed on three occasions. Our bankers placed their special drying rooms at our disposal for some important documents and books – even a laundry gave assistance through the medium of its special apparatus.

Many of our ‘living in’ assistants and fire fighters had lost most of their clothes and personal belongings and for a few days the Guildhall (also badly damaged) was besieged by claimants for compensation. Each was interviewed by the Relieving Officer, and, in most cases, a cash payment on account was made for immediate necessities. A comprehensive form, setting out personal losses had to be completed and returned within 30 days. The administration at the Guildhall was sympathetic and businesslike. There must have been thousands of claims made as a result of the night of December 29th, 1940.

For some time, members of the staff worked among the debris and basements, clearing and salvaging whatever possible. The builders erected scaffolding at certain points with a view to rendering first aid to that part of our remaining building which might be made habitable for business. Meanwhile in Paternoster Row the Royal Engineers and Pioneers were in full possession continuing their work of demolition of unsafe buildings and walls. What remained of the older portion of our building was finally demolished by explosive charges on February 7th, 1941. Despite great damage, it fell only after great reluctance. Paternoster Row and London House Yard remained closed thoroughfares for the rest of the war.

This scene of desolation in the area at the rear of our buildings was terrible. It could be likened to the result of an earthquake. Publishers, publicans, booksellers, scent makers, cafes, solicitors – in fact, all branches of the professions and industry suffered. Notices and papers strung along railings and ropes indicating location of new or temporary addresses could be compared with washing hanging on a line.

The salvaging, drying and storing of a quantity of packing paper and string provided extremely useful, as these commodities became scarcer in supply. Our artesian well which pumped water from a depth of 500 feet in sufficient quantity to supply all our needs, was rendered useless. The reserve tank, for three days’ supply had a capacity of 18,000 gallons and weighed 90 tons. This provided useful salvage and ‘tank-busters’ was no misnomer for the men who were eventually employed to dismantle it.

Finally, we were indeed thankful that no lives were lost, nor serious injury received by any of our staff. Despite the great material losses the Firm sustained they set an example to all in their determination to rise again, Phoenix like, from the flames. Meanwhile over the front entrance door, the sculptured stone figure of ‘Industry’, undamaged, still smiles serenely down on our undertaking.

What further symbol is needed for this great century old business?”

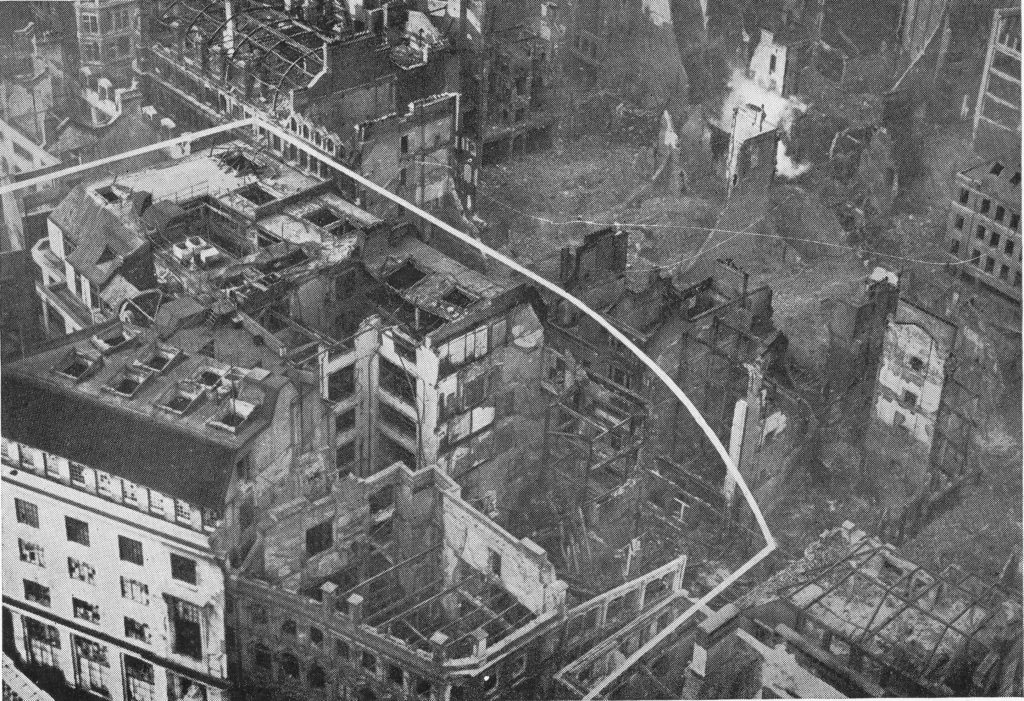

The following photo is titled “Our Block, December 1940”:

In the above photo, the white lines shows the boundary of the premises of Hitchcock Williams & Co and demonstrate the size and scale of their operation around St. Paul’s Churchyard and Paternoster Row. In the lower right corner, part of the shell of a building can be seen with a rather distinctive chimney with lighter colour lower section and darker upper section. This building is the Chapter House of St. Paul’s Cathedral.

My father took a series of photos from the Stone Gallery of St. Paul’s just after the war (I covered these in two posts here and here).

He did not take a photo that exactly covers the area of the Hitchcock Williams building, however he did take the following photo showing the Chapter House with the same distinctive chimney.

In the above photo, the area occupied by the buildings of Hitchcock Williams are to the left and have now been cleared. The round circles are the marks left from the siting of large water tanks that were built after the raid of the 29th December on cleared land. This was to address the problem of water availability and low water pressure as described in the account of the raid.

To help locate where Hitchcock Williams stood in the area around St. Paul’s today, this is a photo I took a couple of years ago when the Chapter House was being restored showing the same view as in my father’s photo above. The premises of Hitchcock Williams were to the left of the Chapter House.

Operation Textiles – A City Warehouse in War-time is a fascinating little book, not just for the account of the 29th December 1940, but also for the background as to how a company operated in the City of London covered in the rest of the book. It is amazing how the company tried to operate as normal in the first months of war, including sending sales representatives with samples to the Channel Islands – they just escaped on the last boat as the islands were being invaded.

The company also appears to have had a very paternalistic approach and was very male dominated as were the majority, if not all of City companies of the time. A photo in the book taken on the roof shows the buyers meeting. Of the 25 staff of buyers, only two were female.

Hitchcock Williams & Co rebuilt their operations during and after the war and continued trading, however changing tastes, foreign competition and the economic recession of the early 1980s all took their toll and Hitchcock Williams closed in 1984. The company had been trading for 149 years and when it closed a fifth generation Williams was a Director of the company.

The area around St. Paul’s Churchyard and Paternoster Row are very different today, having been rebuilt twice since the destruction of the 1940s. Nothing remains of the buildings of Hitchcock Williams, however it is intriguing to wonder if the remains of their 500 foot deep artesian well can still be found somewhere deep under the current incarnation of buildings – something for future archaeologists to wonder about.

To close, here is a poem from the book which describes what must have been the feelings of those who looked over the bombsites of buildings that had been a significant part of their lives:

City Street, 1942

Desolate and gaunt the ruined buildings brood,

And gargoyles from a long dead sculptor’s mood

Still peer, unseeing, grinning in the dust,

Athwart with twisted girders etched with rust,

Who looks unmoved upon these rubbled mounds

Which once knew friends, and heard familiar sounds?

Has compensating Nature spread its gown

Far from the Country to the heart of Town?

Where basements newly greet the sun and showers,

And nourished rockeries grow Summer flowers

My thoughts rebuild the place I used to know

And sadness comes unbid; my voice is low.

The photograph which is captioned, ‘Our firefighting and first aid units’ actually shows members of the St Paul’s Watch, presumably assembled on the roof of Hitchcock Williams & Co. I know this because my father-in-law, Philip Edward Bell, and his best friend, Peter Yates, both feature in this image. Both young men were students of architecture at The Regent Street Polytechnic at the time. They were recruited into the Watch because of their knowledge of architecture. Neither Philip nor Peter had any connection with the haberdashery or textile trade. It is interesting in so far as there was apparently some animosity between the Watch and the surrounding businesses who felt that they were having to play second fiddle to the protection of St Paul’s. This photograph indicates that there must have been some co-operation.

Judy, thanks, that is really interesting. The book implies they are all Hitchcock Williams staff, but obviously not correct. There are some other indications in the book of a common approach, the way they were welcomed into the Crypt perhaps, and also the comment about other companies not protecting their buildings which allowed fires to establish and spread. I found the same views in some of the documentation on the St. Paul’s Watch where they could see fires getting established on the roofs and within locked and empty buildings. Intriguing to wonder if the impact could have been significantly reduced if the majority of buildings were as prepared.

The excellent series of photos “London Night” features a view of the London House Yard second frontage of Hitchcock Williams & Co, with a long-forgotten City pub The Rose and Crown on the corner. I wonder if the pub was the “local” for HW staff.

If I may, here is a link to the photo series. It’s the third photo minimally titled “Street Corner” which shows the scene.

http://spitalfieldslife.com/2013/02/24/london-night/

It took me many weeks to pin down the street location of that photo. It’s the unique layout of the pavement and building frontages plus the detail available to us in the 1890s OS map series which nails it.

London House Yard was apparently named after the former mansion of the Bishop of London. It lay between Paternoster Row and St Paul’s Churchyard. A second pub/tavern along the alleyway, the Goose and Gridiron, was demolished in approx 1890 to make way for HW’s expansion; the tavern’s own history is worth a delve.

Thank you so much for the detail on HW & Co. We are indeed lucky to have so much of London’s rich history available on our screens every week as a result of your tireless effort. And what a fascinating district the St Paul’s area must have been to wander through before so much of it was laid waste.

on one night in the Blitz 27.000 bombs fell on the City and that is the memorial shown

I find the comments about people claiming compensation intriguing. I guess an awful lot of people were involved in administering red tape. Very necessary, but not an activity that gets much mention.

Brilliant article as usual, st Paul’s is still for me the most iconic building in London because of that very famous photo after the bombing, I still walk all around that area -if you could only turn the clock back .

Thanks keep them coming .

My mother aged 14 in 1939 started her first job as a post girl with this company. She had a uniform to wear as she took post around the city for the company and sorted incoming mail for various departments.

After the fire she went in to work for the FBI, in those days the Federation of British Industries (now the CBI) after taking herself to night classes to learn shorthand and typing.

She lived at home in Brixton and during the Blitz often had hair raising tales of lifts on backs of lorries to get to work when roads were bombed and buses couldn`t run.

Fascinating, poignant and very moving. Thank you.

Thank you,Admin, for all the very interesting and informative posts during 2018. Wishing you and all your readers a Happy and Peaceful New Year!

St Paul’s was not burned down. Could this have been due religious respect om the part of the German airmen?

What a wonderful endeavour! I was looking for pre war photos around the St Paul area. I am wondering if your father’s curiosity drove him to take all these wonderful photos or was he a professional photographer?

Hi Judith, he was just a very enthusiastic amateur photographer who also had a love of London.

Must have been amazing to have such a father. Amateur photographers there were/are many, but to be such chronicler takes a very particular mindset. Were you in any way aware of him being extraordinary? I am asking because as children we tend to take so much for granted.

Best wishes for 2019 and many thanks

I was very interested to see these photos of the destruction of the Hitchcock Williams’ warehouse as my great grandfather was director of a similar textile warehouse firm in Bread Street, a little way to the back of St Paul’s. It was called William Williams and occupied 6 warehouses in Bread Street and 6 in Watling Street. The latter was destroyed by fire on September 10th 1940, despite an up to the minute sprinkler system. The reserve warehouse in Milton Buildings had an air raid shelter for up to 180 people and was undamaged. After rebuilding, the firm survived another severe raid on the City on January 6th 1941 but on January 11th was finally destroyed again by yet more bombing. I believe the famous photo of the postman among the rubble of bombed buildings with St Paul’s in the background was in fact outside William Williams’ warehouses in Watling Street, (though the photo was posed.) The firm relocated to Chesham for a time and in 1944 moved to Aldersgate Street. Like so many family firms in London, it was left behind by changing patterns of trade and closed in 2006. It’s amazing to think now that for a hundred years that part of the City was occupied by drapers’ warehouses and the ‘Textile Distributing Trade’ where there are now powerful banks and finance houses.

I’m researching George Hitchcock on behalf of YMCA Exeter and this article is fascinating. I’m trying to trace an image of the portrait of Hitchcock given to him by his workforce during mid 19th century. Have you ever come across a portrait of him in your research? Thanks so much.

Great work , brilliant article, very interesting and informative post.

I have some volumes of the book ” Second World War ” – Winston Churchill , and in three volumes (1949, 1951,1954 ) there are a hand writing notes from the directors of “Hitchcock, Williams & Co” giving good wishes for Christmas and New Year

thasmylife@hotmail.com