The Festival of Britain South Bank Exhibition occupied the site on the South Bank that I have been exploring in the last few posts. The South Bank Exhibition was the largest part of what was a national exhibition with events across London and the whole country. The Festival of Britain was very much a product of its time and attempted to provide visitors with a multi-layered view of Great Britain – the land and people, history, achievements in science, industry, art, design and architecture and a view of what the future held for a unified and confident people.

Whilst both London and the rest of Great Britain is now a very different place to 1951, researching the Festival of Britain in parallel to the EU Referendum brought home a number of common themes:

- what is Great Britain and who are the British

- Great Britain’s place in the world, and a focus on Europe or Empire

- the politics of the country and the influence of the press

In this post I will try to provide an overview of the Festival of Britain and in the next two posts take a walk around the South Bank site. This is a personal view and only very lightly scratches the surface of the politics and British society at the time, and the complex organisation of highly talented people who put together the Festival of Britain in a very short period of time and whilst the country was still recovering from the war.

The view of Britain portrayed at the Festival may today seem very dated, however it is still possible to recognise many of the views of Britain from the Festival and 1951 in the Britain of today. It is also possible to see how the vision of the future portrayed at the Festival has turned out very differently.

Again, I can only scratch the surface. There are a number of excellent books on the Festival of Britain and I have listed these at the end of the post.

Background to the Festival of Britain

The possibility of some sort of festival had been raised a number of times from the middle of the last war, however it was when Gerald Barry, the editor of the News Chronicle wrote an open letter in the paper to Stafford Cripps, the President of the Board of Trade that the idea started to gain support.

The initial idea was along the lines of pre-war International Exhibitions and similar to the 1851 Exhibition, however the cost of such an exhibition would have been considerable and given the country’s financial state in the immediate post war period, a much reduced festival was agreed by the government. The festival was to be a “Festival of Britain”. Commemorating the centenary of the 1851 festival, and also providing a much-needed boost to the population after years of war and the continuing rationing and austerity of the post war years. The Britain in the name of the title also demonstrated that the festival was to focus on the country of Great Britain rather than the Empire, which had been the subject of previous exhibitions and festivals.

The Labour MP Herbert Morrison was placed in charge of the planned festival. (His grandson, Peter Mandelson would later be responsible for the Millennium Dome).

Although Morrison intended the festival to be non-political, it was given the go-ahead by a Labour Government and many of the themes of the festival were aligned with the thinking and policies of the Labour Government at the time. The festival was not supported by many members of the Conservative Party, or by much of the right-wing press, mainly the newspapers owned by Lord Beaverbrook such as the Daily Express and the London Evening Standard.

Newspaper headlines were openly critical of the festival, for example complaining about the waste of resources when the country needed more housing and factories. Beaverbrook was also an Empire loyalist and would later oppose Britain’s application to join the European Economic Community the predecessor of the European Union.

The focus of the festival was Great Britain and its core theme was the idea of an ordinary people with deep historic roots that were closely tied to the land. An innovative people who had made use of the opportunities provided by a rich landscape and land to make significant contributions to civilisation through art, design, architecture, science and industry. The theme also put forward “two of the main qualities of the national character: on the one hand, realism and strength, on the other, fantasy, independence and imagination”.

Unlike previous exhibitions, the Festival of Britain would be a journey, taking the visitor on a journey from the earliest geology of the country, to the first human arrivals and the later waves of immigration that would build the British population. It did though show a very limited view of this journey. As well as there being hardly any mention of the Empire, the story of immigration to the country ended with the Norman invasion and did not cover later arrivals such as the Huguenots, or immigration from the rest of the Empire.

As well as the historic story of the land and the British people, the Festival of Britain would also be forward-looking. The festival would show how innovation and design, science and industry would build a far better future for the country and would show visitors how new ideas, products, design and scientific exploration would benefit them in the future after years of war and austerity.

The Festival of Britain was not just intended for the British public, it was also expected that the festival would help bring in tourists from across the world along with their much-needed foreign currency.

The South Bank Festival of Britain was the main location and continues to be the site most associated with the festival, however it was planned to be a festival across the whole of Great Britain, with the intention that every town and village would get involved and do something in the name of the festival. This may be a carnival, it could be to tidy up part of a town after the lack of maintenance and manpower during the war, it could also be planting trees – anything that would help celebrate the festival and involve the community.

Within London there were a number of main events:

- the main Festival exhibition on the South Bank

- a Festival of Science at the Science Museum in Kensington

- a Festival of Architecture at the new Lansbury Estate in Poplar, East London

- the Festival of Britain Pleasure Gardens at Battersea Park

The Pleasure Gardens at Battersea were considered an essential balance to the educational and informative tone of the rest of the festival, although the prevailing view at the time was that there was a genuine public thirst for knowledge. The popularity of educational broadcasts during the war, army educational initiatives and the number of people attending night schools all supported this view which also aligned with Labour policy of the time.

Outside of London there were major festival events that would focus on the strengths of the individual countries of Great Britain and would also ensure that the festival was available to the majority of the population of Great Britain. These included the:

- Belfast – Farm and Factory exhibition

- Glasgow – Industrial Power: Coal and Water exhibition

There was also a travelling exhibition on board a decommissioned aircraft carrier, the Campania which traveled the coast of Great Britain, visiting key coastal towns and cities.

There was also a land based travelling exhibition which went to Manchester, Leeds, Birmingham and Nottingham.

The arts were represented by events across the country, for example:

- Stratford – Shakespeare and his Histories

- Bournemouth – The Arts at Bournemouth

- Norwich – The Arts in a Country City

- Liverpool – The Port, the City and the Arts

- Llangollen – The National Eisteddfod

- Aberdeen – The Festival in Aberdeen

The Festival of Britain was fully intended to cover the whole country and involve as much of the population as possible.

The Lion and the Unicorn

The Lion and the Unicorn pavilion on the South Bank shows how the Festival of Britain wanted to portray the British people both within Great Britain and to visitors from abroad.

The South Bank Festival guidebook offers this introduction to the pavilion:

“The British people are something more than the sum of: men with ancestors, children in schools, families in homes and gardens, and patients in hospitals. They are, in addition, compositions of various particular habits, attitudes, instincts, qualities and characteristic moods. But these attributes, not being tangible, are hard to display, “in the round”, in an exhibition of tangible things.

Nevertheless, we should not like visitors – particularly those from overseas – to leave the South Bank without having seen, at least, some token and visible reminders of the British people’s native genius. So, this Pavilion offers one or two clues to their character”.

The attributes that the pavilion presented were:

Language and Literature: showing how the English language has grown from being used by a “huddle of British Islanders” to being used by 250 million people. How the English Bible, Chaucer, Shakespeare, T.S. Elliot, Defoe, Swift, Sterne, Carlyle, Dickens and Lewis Carole have used the English language to create works that have helped grow the usage of the language and embody the British character in their works.

This is another example of where the Festival avoided references to the Empire which probably did far more to spread the use of English than many of the literary works of the countries authors.

Eccentricities and Humours: a characteristic of the British people being their love of eccentric fantasy.

Skill of Hand and Eye: the long tradition of British craftsmanship demonstrated by old furniture, sporting guns, fishing tackle and tailoring and how British artists such as Gainsborough and Constable have expressed the British landscape, along with the applied arts such as textiles, china and wallpaper.

The Instinct of Liberty: where the British have a continuing impulse to develop and enlarge the opportunities for freedom of worship, freedom of government and personal freedom. Examples given being the Magna Charta, the freedom of the press, the Tolpuddle Martyrs, the suffragettes.

The Indefinable Character: Here the guidebook sums up the challenge of understanding what it means to be British. It suggests that after leaving the pavilion the visitor from overseas may “conclude that he is still not much the wiser about the British national character, it may console him to know that British people are themselves still very much in the dark about it”.

The name of the pavilion which attempted to define the British people is also the title of an essay written in 1941 by George Orwell which also seems to be putting forward many of the same views of Britain and the British people as the Festival.

The essay was written when, as the first sentence describes “As I write, highly civilized human beings are flying overhead, trying to kill me.”

The Festival of Britain described the British as a family, Orwell refers to the English and that they are different to the rest of the world and also the historical continuity (which was also a theme of the festival) which binds the English people:

“When you come back to England from any foreign country, you have immediately the sensation of breathing a different air. Even in the first few minutes dozens of small things conspire to give you this feeling. The beer is bitterer, the coins are heavier, the grass is greener, the advertisements are more blatant. The crowds in the big towns, with their mild knobby faces, their bad teeth and gentle manners, are different from a European crowd. Then the vastness of England swallows you up, and you lose for a while your feeling that the whole nation has a single identifiable character. Are there really such things as nations? Are we not forty-six million individuals, all different? And the diversity of it, the chaos! The clatter of clogs in the Lancashire mill towns, the to-and-fro of the lorries on the Great North Road, the queues outside the Labour Exchanges, the rattle of pin-tables in the Soho pubs, the old maids hiking to Holy Communion through the mists of the autumn morning – all these are not only fragments, but characteristic fragments, of the English scene. How can one make a pattern out of this muddle?

But talk to foreigners, read foreign books or newspapers, and you are brought back to the same thought. Yes, there is something distinctive and recognizable in English civilization. It is a culture as individual as that of Spain. It is somehow bound up with solid breakfasts and gloomy Sundays, smoky towns and winding roads, green fields and red pillar-boxes. It has a flavour of its own. Moreover it is continuous, it stretches into the future and the past, there is something in it that persists, as in a living creature. What can the England of 1940 have in common with the England of 1840? But then, what have you in common with the child of five whose photograph your mother keeps on the mantelpiece? Nothing, except that you happen to be the same person”.

But Orwell brings out the contradictory nature of the English people – the opposite of the Festival of Britain which after the experience of the war presented the view of the British as a family.

“And yet the gentleness of English civilization is mixed up with barbarities and anachronisms. Our criminal law is as out-of-date as the muskets in the Tower. Over against the Nazi Storm Trooper you have got to set that typically English figure, the hanging judge, some gouty old bully with his mind rooted in the nineteenth century, handing out savage sentences. In England people are still hanged by the neck and flogged with the cat o’ nine tails. Both of these punishments are obscene as well as cruel, but there has never been any genuinely popular outcry against them. People accept them (and Dartmoor, and Borstal) almost as they accept the weather. They are part of ‘the law’, which is assumed to be unalterable”.

and:

“England is a family with the wrong members in control. Almost entirely we are governed by the rich, and by people who step into positions of command by right of birth. Few if any of these people are consciously treacherous, some of them are not even fools, but as a class they are quite incapable of leading us to victory”.

and as part of the final section of the essay titled “The English Revolution”, Orwell states:

“An English Socialist government will transform the nation from top to bottom, but it will still bear all over it the unmistakable marks of our own civilization, the peculiar civilization which I discussed earlier in this book.

It will not be doctrinaire, nor even logical. It will abolish the House of Lords, but quite probably will not abolish the Monarchy. It will leave anachronisms and loose ends everywhere, the judge in his ridiculous horsehair wig and the lion and the unicorn on the soldier’s cap-buttons. It will not set up any explicit class dictatorship. It will group itself round the old Labour Party and its mass following will be in the trade unions, but it will draw into it most of the middle class and many of the younger sons of the bourgeoisie. Most of its directing brains will come from the new indeterminate class of skilled workers, technical experts, airmen, scientists, architects and journalists, the people who feel at home in the radio and ferro-concrete age. But it will never lose touch with the tradition of compromise and the belief in a law that is above the State. It will shoot traitors, but it will give them a solemn trial beforehand and occasionally it will acquit them. It will crush any open revolt promptly and cruelly, but it will interfere very little with the spoken and written word. Political parties with different names will still exist, revolutionary sects will still be publishing their newspapers and making as little impression as ever. It will disestablish the Church, but will not persecute religion. It will retain a vague reverence for the Christian moral code, and from time to time will refer to England as ‘a Christian country”.

Although some of Orwell’s statements, such as the abolition of the House of Lords has not happened, much of the above paragraphs does describe the post war Labour Government and the key people involved in the development of the Festival of Britain.

Whilst Orwell identifies the English as a family, but with the wrong members in control, a central aim of the Festival of Britain was also to show the British as a family – a family with differences, but with a core set of attributes as shown in the Lion and the Unicorn pavilion, and a family with a long, shared history and common roots from the pre-1066 Norman conquest.

The festival also stated that “Britain is a Christian Community” with the official book of the festival claiming that the Christian faith is inseparably a part of our history, and that it has strengthened all those endeavours which the festival has been built to display. There was no exhibit on the South Bank site to cover this element of the national character, however the church of St. John’s on Waterloo Road was designated as the Festival Church with daily services and events for the duration of the festival.

The festival film, Family Portrait by Humphrey Jennings for the Central Office of Information provides an insight into the story that the Festival of Britain aimed to portray about the British. It is well worth a watch to understand the thinking behind the festival.

The film can be found here. (Humphrey Jennings was an English documentary film maker who worked for the Ministry of Information during the war. He was also one of the founders of Mass Observation. The film Family Portrait was completed in 1950 ready for the festival of the following year, however Jennings died in 1950 after a cliff fall).

Designing the Festival

Orwell stated that “Most of its directing brains will come from the new indeterminate class of skilled workers, technical experts, airmen, scientists, architects and journalists, the people who feel at home in the radio and ferro-concrete age” and this was very true of the Festival of Britain.

Gerald Barry, the Festival’s director was a journalist and editor of the News Chronicle.

Gordon Russell who was the director of the Council of Industrial Design was responsible for how industrial design was represented in the festival. Huw Wheldon represented the Arts Council and the festival’s director of science and technology was Ian Cox from the Ministry of Information.

The festival team was made up of designers and architects who qualified during the 1930s and worked on wartime design projects (e.g. specialist camouflage techniques), temporary and travelling exhibitions such as the Army exhibition on the site of the bombed John Lewis store in Oxford Street, and members of groups such as the Modern Architecture Research Group.

Designers and architects such as Misha Black, Ralph Tubbs, Hugh Casson , james Holland and Abram Games who was responsible for the design of the Britannia and Compass symbol for the festival which was used across all festival locations and activities, not just at the South bank.

Abram Games symbol for the festival on the cover page of the guide-book to the South Bank:

Each of the main themes at the festival had a core team who were responsible for the architecture, the theme and the display design, for example, for the first part of the story “The Land”, the team responsible for the direction were Misha Black for Architecture, Ian Cox for the Theme and James Holland for the Display Design. Individual pavilions and sections then also had an architect, theme convener and display designer. This approach ensured that a common, consistent theme could be applied to the main parts of the story that the festival would tell, whilst individual sections would have their own specialist team.

Other people involved with the creative design of the Festival of Britain included Laurie Lee, the author of Cider with Rosie, who wrote much of the text to go with the exhibition. The textile and furniture designer Ernest Race designed the innovative Antelope chair which was used across the Festival of Britain site.

The architecture of the festival was mainly Modernist in style and meant to reflect the social democratic and egalitarian approach to how design would build a new Britain. This would be seen in the schools, hospitals and public buildings that would be built across the country.

There were many pieces of sculpture across the South Bank, including works by Barbara Hepworth and Henry Moore, along with major painted murals across the site, for example Seaside Family by Carl Giles at the Seaside display and Country Life by Edward Bawden in the Lion and the Unicorn pavilion. The intention of the festival was also to make sculpture and art in general more accessible to the general population.

A number of the buildings across the site needed specialist technical expertise to design, engineer and build buildings that were the first of their type. For example Ralph Tubbs was the architect of the Dome of Discovery, Freeman, Fox were the consulting engineers who helped to work out how to construct the building which at the time was the largest span (365 feet) in the world. The construction company Horseley Ironworks were responsible for the build of the Dome which again as a first for a building of this size and shape used aluminium.

In showing British contributions to civilisation, British architecture, design, art and engineering was core to the festival.

A Visit to the Festival on the South Bank

As described above, the festival would show that the British are a family with a deep-rooted history, the character of the British, and British contributions to science, architecture, design, engineering and art and this would all be covered on the South Bank.

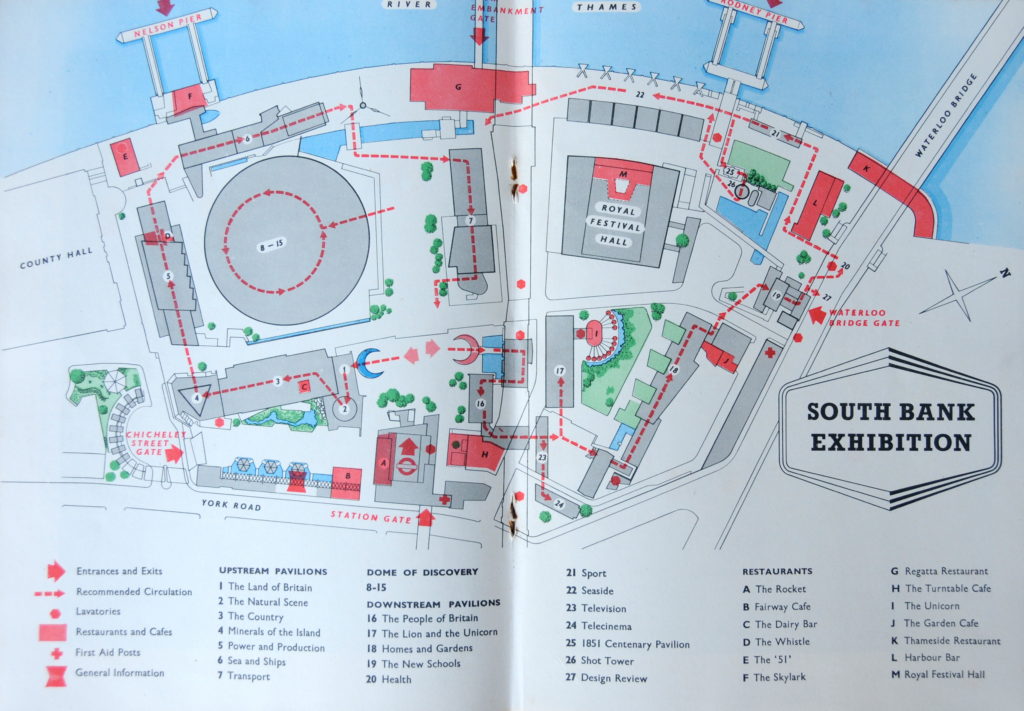

The map below shows the Festival site:

Covering the area enclosed by the river, Waterloo Bridge, County Hall and York Road with Hungerford Bridge cutting the site in two. the same area of land I covered in my last three posts on the South Bank.

Although the buildings appeared to be randomly placed, there was a structure to the site and a route around the festival that would tell a story to the visitor. The apparent random placement of buildings and pavilions helped to give the impression that the site was larger than it was. The area was relatively small for such a complex exhibition and the random placing of buildings meant the route around the exhibition was not obvious and also gave the opportunity for the visitor to discover hidden little parts of the exhibition and different views.

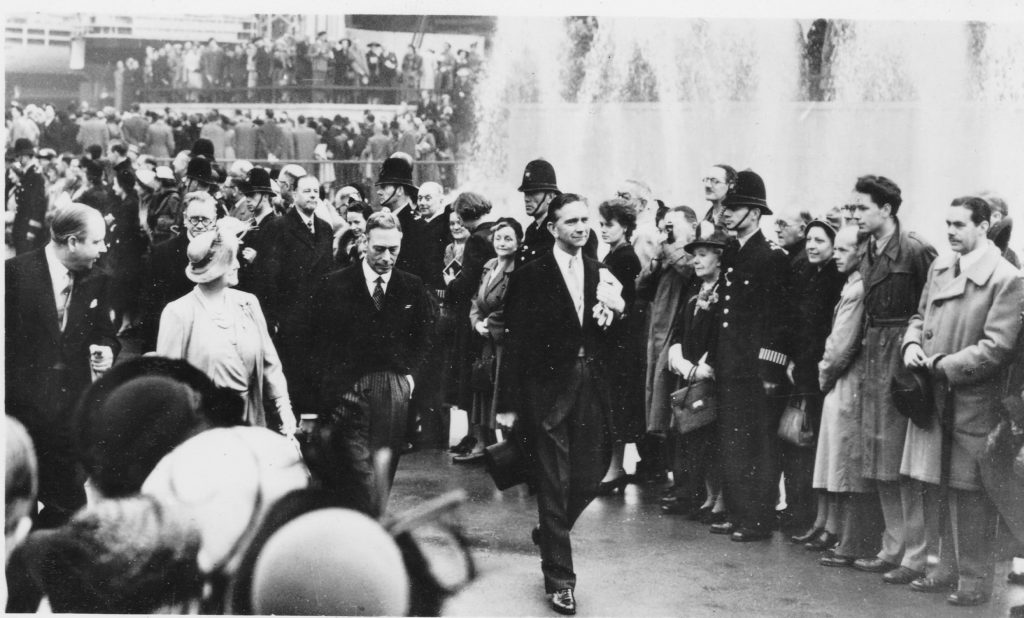

The official opening of the Festival of Britain was on the 3rd May 1951. A special service was held at St. Paul’s Cathedral and in the afternoon King George VI and Queen Elizabeth attended a ceremony of dedication at the Royal Festival Hall.

Postcards above and below showing the King and Queen at the festival site.

I do not know why, but my father did not take many photos of the festival, however a couple of his photos show the flags around St. Paul’s Cathedral for the Festival of Britain:

By the time the festival closed on the 30th September 1951, almost 8.5 million people had visited the South Bank site. The public enthusiasm and the support of the King and Queen for the festival resulted in the papers which had been so hostile before the opening of the festival, now being supportive.

The General Election on the 25th October 1951, soon after the festival closed, resulted in a Conservative Government led by Winston Churchill who had always been critical of the Festival of Britain. The decision was made that the festival site should be demolished as quickly as possible, including the major landmarks of the site, the Dome of Discovery and the Skylon – only the Royal Festival Hall would remain.

In my next two posts I will take a walk around the South Bank site following the suggested route from the guidebook to see the pavilions and what the site looks like today.

There are a number of excellent books on the subject of the Festival of Britain. Books I have read and recommend include:

- The Festival of Britain, A Land and its People by Harriet Atkinson

- The Autobiography of a Nation by Becky E. Conlin

- Festival of Britain – Twentieth Century Architecture 5. The Journal of the Twentieth Century Society

- A Tonic to the Nation by Bevis Hillier and Mary Banham

- The Lion and the Unicorn by Henrietta Goodden

- Festival of Britain Design by Paul Rennie published by the Antique Collectors’ Club

- Abram Games Design by Naomi Games and Brian Webb published by the Antique Collectors’ Club

Hello,

My father,Bill Ellis,was a carpenter involved in the construction of the Royal Festival Hall.He was really amazed that, before it was glazed,the trains on the bridge next to the Hall were inaudible, such was the level of sound-proofing even at that stage in construction.Unfortunately,I know little else of the construction,but I do remember enjoying a really wonderful day out with my family on a visit to the exhibition,once opened.I was 7 years old and thoroughly enjoyed the visit.

My mother worked on the turnstiles at the Festival Of Britain. Aged 10, I went every day and was lifted over the gates. I believe I might have been the only person who saw everything there!

Then aged seven I remember the steam locomotive built for the Government of India and Rowland Emmet’s

comic railway in Battersea Park. Did we travel by boat from South Bank to Battersea?