St Mary Woolnoth is an unusual church. A short distance from the Bank, the church can be found at the junction of Lombard Street and King William Street. St Mary Woolnoth has one of the more unusual towers of the City churches, a Hawksmoor church, built after post Great Fire repairs to the medieval church failed, a church that survived the blitz, but 50 years earlier had almost been lost to the City and South London Railway.

The view of St Mary Woolnoth from the Bank junction.

The church occupies a small space, surrounded by City offices and from this perspective, the unusual tower is clearly viewed.

The current church was built between 1716 and 1727 by Nicholas Hawksmoor. The previous church had partly survived the Great Fire of 1666, but needed considerable repair. This work was carried out from 1670, but there were obviously problems repairing a medieval church which led to the decision for Hawksmoor’s replacement church in the early decades of the 18th century. The new church was part of the plan for 50 new churches, funded by a tax on coal.

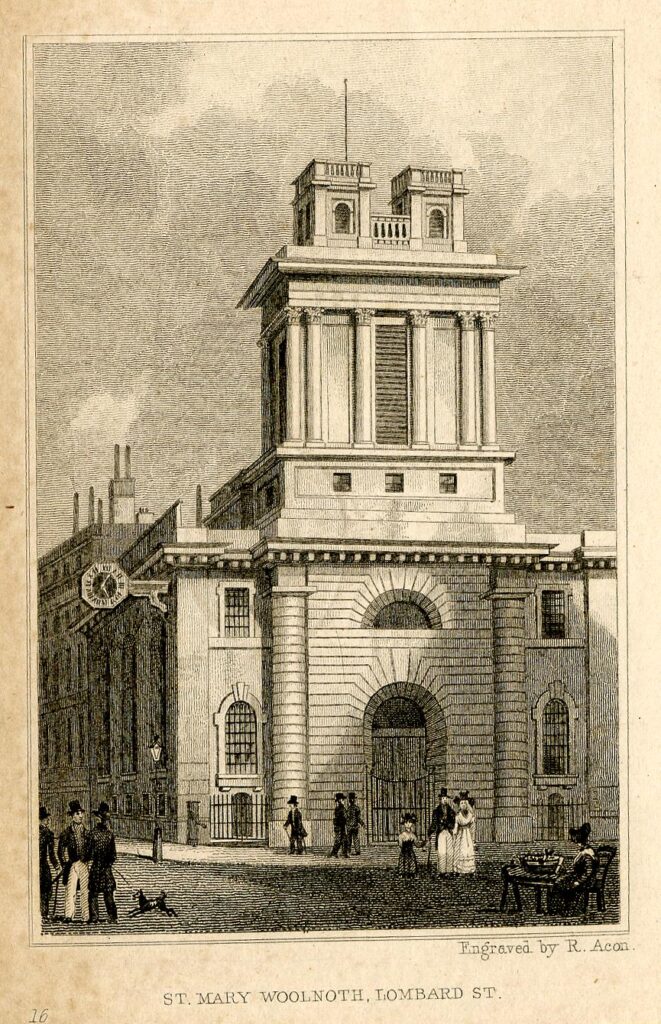

The tower is interesting. From the front it is substantial and broad, but look from the side and the tower is narrow. Four columns give the impression of two separate towers, this view being reinforced by the two small turrets rising at the top. The turrets are small versions of the square towers that would normally be expected on a City church.

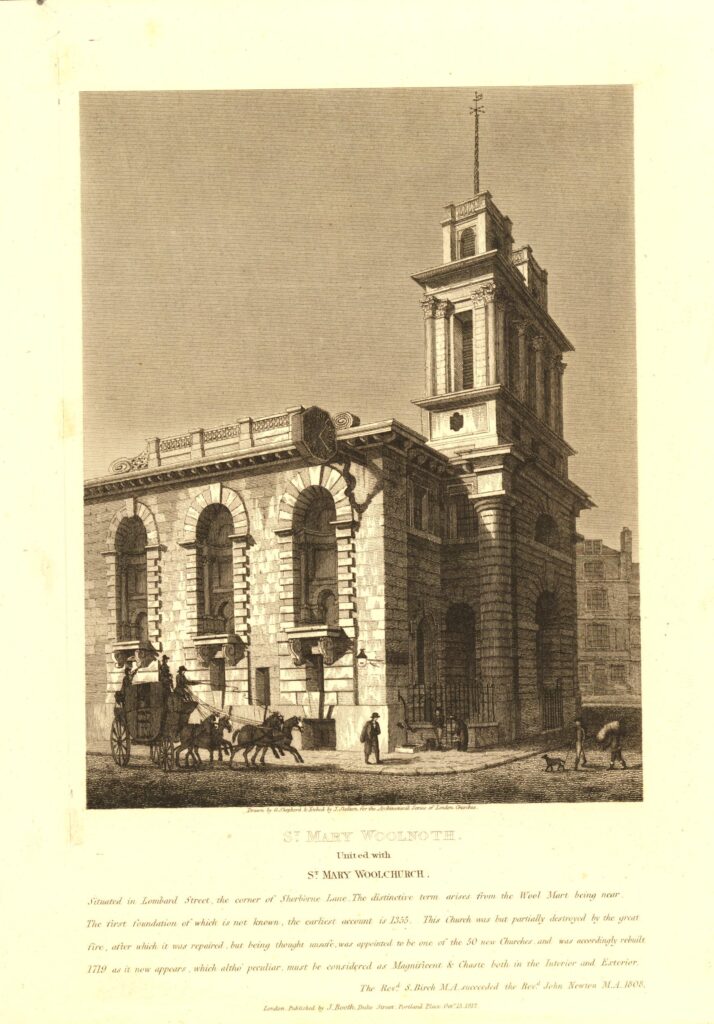

This print from 1838 shows St Mary Woolnoth when the tower of the church was still higher than the surrounding buildings. Note the clock on the left wall of the church, over hanging the street. The clock is still a feature of the church today.

As well as the tower, another feature of the church is one that almost led to its destruction. If you look along the King William Street side of the church, there is an ornate wall projecting out from the corner of the church, today being the location for a Starbucks. In the far arch of the wall can be found the entrance to a lift.

The City and South London Railway had opened in 1890. The railway had originally been planned to run from King William Street to the Elephant and Castle, however extensions were being quickly implemented and the line would eventually become the eastern branch of the Northern Line.

The City and South London Railway required space around the Bank in what was already a very congested area. The late 19th century was a time when a number of City churches were demolished as the population of the City had declined and there was no longer a sufficient congregation for what was still a number of churches that suited the Medieval City rather than the Victorian City.

Although proposals for the demolition of the church were put forward, a compromise was agreed, as detailed in the following report from the Standard on Friday November 23rd 1900:

“In 1893 the Railway Company obtained an Act for making a railway, and under that Act they scheduled the site of the church. Owing to the lack of means there was no opposition to the Act on the part of the churchwardens, and the only portion of the Act which affected the church was the clause relating to the removal of human remains which might be disturbed.

Nothing was done till 1896, when the Company obtained an Act to extend the period for the construction of the line. Opposition was then raised by the present Claimants and the Bill was opposed in both Houses, though in the protection of public monuments. the result was that in the Act a clause was inserted that the Company could not purchase any part of the church, but only portions of the land adjacent and under the church, and the clause provided that the arbitrator, in considering the compensation, should take into account the additional cost to the Company of this change to their plans.

in February 1897, the Company under their powers served notice on the Churchwardens, and shortly afterwards took possession of the church and carried on their works. These works had been in progress nearly three years, and all the Company had done was strictly within their rights. On the lands they had made approaches to the station, which was formed of the crypt of the church, and was 4ft above ground level. So far as the engineering went, it was a wonderful piece of work”.

It was indeed a wonderful piece of work. The church lost its crypt, which became part of the station infrastructure for the City and South London Railway, and the church above ground was strengthened with steel reinforcement.

Most importantly, it was a compromise which ensured this unique Hawksmoor church would survive.

The side of the church facing King William Street is now masked by what was the former Underground Station, designed by Sidney R.J. Smith and built between 1897 and 1898 as part of the works described in the Standard article above.

The Pevsner “London: The CIty Churches” does not think much of the facade, describing it as “a Hawksmoorish rusticated centrepiece, let down by mediocre flanking figures in low relief”.

The arch on the right provides access to a lift for step free access to the Northern Line platforms – the old City and South London Railway.

The churchwardens probably regarded the loss of the crypt as an extremely good result as only a few years earlier the church had to be closed because of the state of the crypt. This also sheds light on what an appalling state most City churches must have been in during the 19th century until their crypts were cleared. The following article explains:

“One of the oldest churches in the City of London has actually had to be closed in consequence of the effluvia arising from the dead bodies in the vault. This is St Mary Woolnoth. The congregation who worshiped there were not only annoyed, but made ill, and the clergyman, after the three services, generally went home with a sore throat. At times there would be no smell in the church, at others an intolerable odour came up in whiffs and gusts. It is computed that the remains of between seven and eight thousand bodies are massed together within a few feet of the floor”.

So the City and South London Railway fixed the problems with the crypt and the churchwardens received back a strengthened church, although now without a crypt.

The article mentions that the church is one of the oldest in the City. There appears to have been a church on the site in the 12th century. The church was rebuilt in 1438, and it was this church that was badly damaged in the Great Fire.

There are a number of explanations as to the name “Woolnoth”. Pevsner states that the name “probably commemorates an 11th century founder named Wulfnoth”. Wilberforce Jenkinson in London Churches Before The Great Fire (1917) links the name with the wool trade.

This print from 1812 also associates the name of the church with the wool trade stating that “the distinctive term arises from the Wool Mart being near”.

The side view of the church in the above print shows how narrow the tower is from the side, compared with the width of the front view.

Another view of the church from around 1830 with a good view of the clock.

The interior of St Mary Woolnoth is relatively compact, Three large columns on each corner support a square opening, above which there is a space with an arch shaped window on each side, with a chandelier hanging from the centre of the ceiling.

Surrounding the altar is some impressive woodwork, with two ornately carved columns supporting a canopy decorated with gilded cherubs.

View up to the roof. It was overcast on the day of my visit, and the windows do not let much natural light through to the church interior below.

The organ gallery and organ case above the entrance to the church. According to the Pevsner guide, the organ case dates from 1681, so perhaps it was part of the post Great Fire restoration of the medieval church, and was saved for use in Hawksmoor’s church.

In a corner of the church is a clock mechanism:

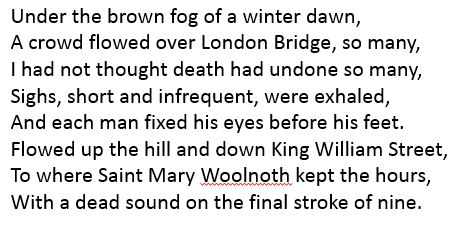

The mechanism is within a perspex cover, and just below is printed an extract from The Waste Land by TS Eliot:

Thomas Stearns Eliot was an American who moved to England in 1914 when he was 25 and became a UK citizen. In The Waste Land, Eliot is concerned about the state of Europe in the 1920s and the impact the modern world is having on the cultural, spiritual and moral state.

He worked in the City for a bank, so must have known the area well, and the description is of City workers flowing over London Bridge, up and down King William Street as they make their way to work, with the clock at St Mary Woolnoth reminding them of the time they needed to be in their offices.

Although written in the 1920s, it is a scene that could still be seen up until March of this year, and I suspect Eliot would be just as concerned today as he was then about the moral state of the world.

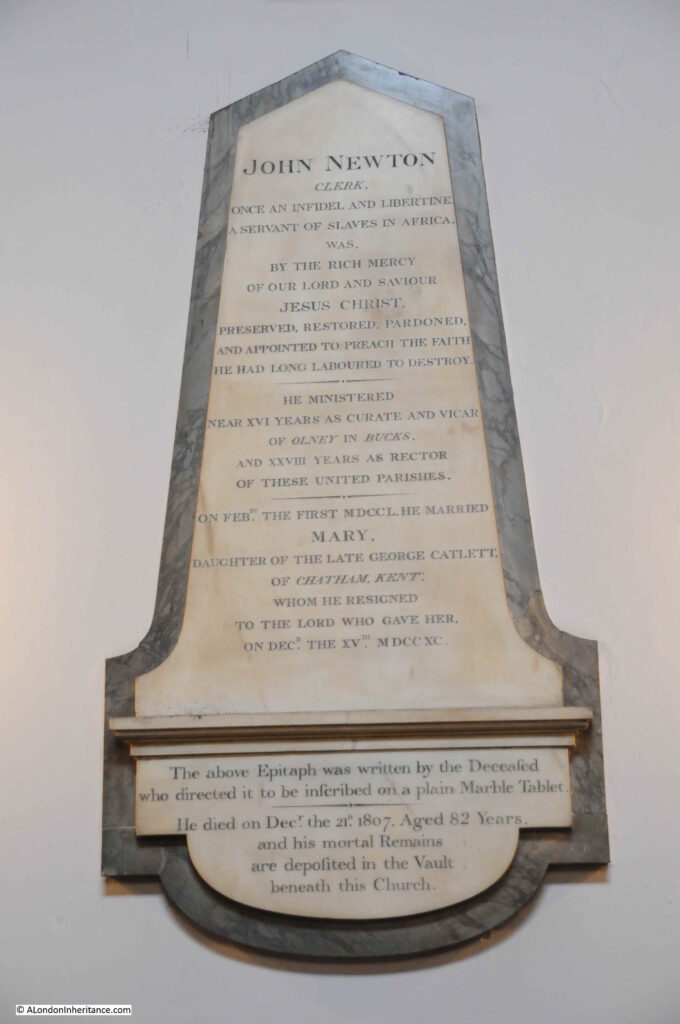

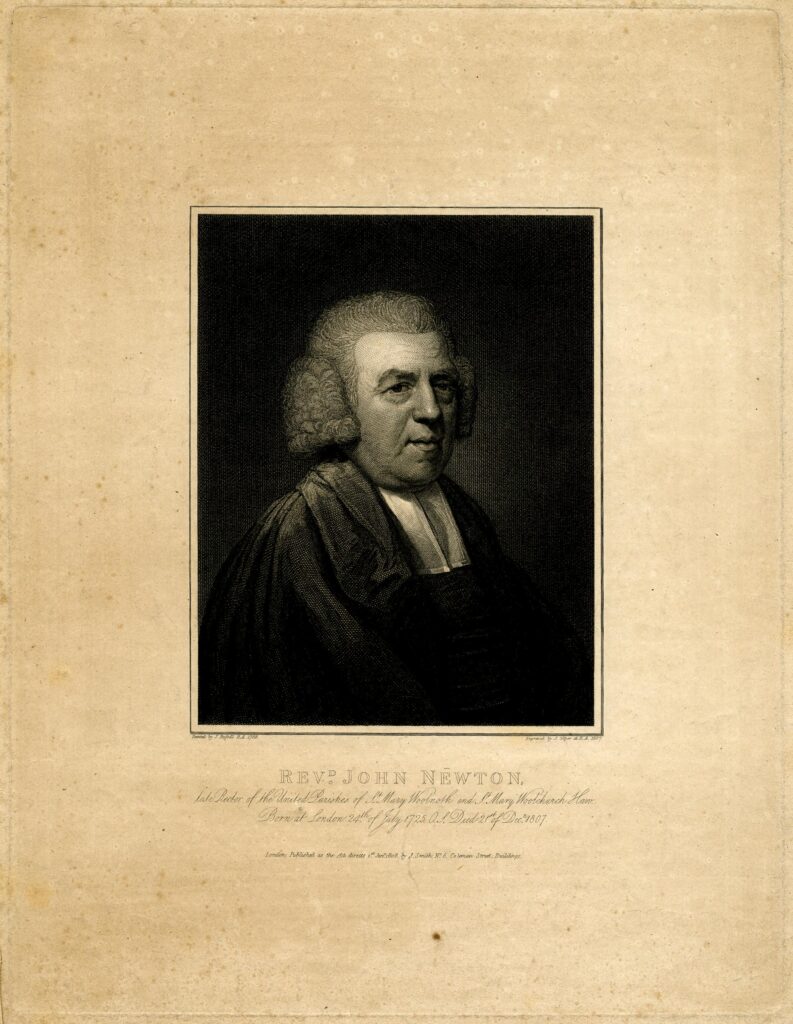

St Mary Woolnoth has a memorial to perhaps the most celebrated rector of the church, John Newton:

John Newton was born in Wapping in 1725, the son of a Master Mariner, so his life at sea was as good as guaranteed. His early career at sea was in the slave trade, working on slave ships, including three voyages as captain. In 1748 he converted to Christianity and from the same year worked as the Surveyor of Tides in Liverpool. During his time in Liverpool he studied theology and although considered a radical, finally found a position as curate at the church of Saints Peter and Paul in Olney, Buckinghamshire.

Whilst he was at Olney, he worked with the poet William Cowper on a collection of hymns which included Amazing Grace.

His time at St Mary Woolnoth started in 1780 when he became rector of the church. During his time at the church, he supported William Wilberforce, he published a pamphlet titled “Thoughts upon the African Slave Trade” in which he wrote about his time as a slave trader, wrote about his regret of his role and was outspoken in his condemnation of the slave trade.

He supported the Committee for the Abolition of the Slave Trade which had been formed in 1787, and the committee purchased copies of Newton’s pamphlet to be sent to every member of the House of Commons and the House of Lords

John Newton provided evidence to the parliamentary committee set up to examine the slave trade, and used his experience as a slave trader to speak about the appalling conditions of the trade.

The law to abolish the slave trade, the Abolition Act passed into law and soon after, in December 1807, John Newton died. He was buried in the crypt of St Mary Woolnoth, alongside his wife.

When the crypt was cleared for the construction of the Underground station, the bodies of John and his wife Mary were moved to the church in Olney where he had been churchwarden.

Newton’s pamphlet “Thoughts upon the African Slave Trade” provides a very clear account of the unbelievable cruelties of the trade and makes for a very harrowing and upsetting read.

The Cowper and Newton Museum in Olney can be found here, and they also have a copy of the pamphlet in PDF form which can be downloaded from the following link:

https://www.cowperandnewtonmuseum.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2012/01/thoughtsuponafri00newt.pdf

The Reverend John Newton:

St Mary Woolnoth is an important church. A church has been on the site since the 11th century. Architecturally, it is a fine example of Hawksmoor’s work. The church survived the arrival of the Underground railway and suffered minimal damage during the blitz.

Many millions of City workers must have looked up at St Mary Woolnoth’s clock on their way to and from work, and from John Newton we can learn first hand about the appalling cruelties of the slave trade.

Fantastic article as always. Thanks for everything you do- really appreciated!

Thank you very much for a great article on St Mary Woolnoth. I am particularly interested in this church as my Great Great Grandfather married there twice in 1848 and 1862. The prints show me a more accurate view of what the surrounding area was like at the time of the marriages .

“the line would eventually become the eastern branch of the Northern Line.” Or the City/Bank branch – not sure I’ve ever heard it called the eastern branch before! The church’s relationship to the commercial buildings immediately behind is interesting, especially the current buuding which retains fragments of its post war precedessor on show in the public passageway.

Forty years ago the site that is now Starbucks in King William Street was occupied by a British Rail booking office, handy for purchasing business travel or weekend tickets before the web world and one avoided having to go to a mainline station.

As strange a development story as one in likely to come upon. Thank you!

I miss London so much but I cannot travel during pandamic, so I have to wait like all other people. I live in Germany, Hamburg. When I sit at home, I try to get as much information about your wonderful city as I can get. Today I read this article about the church in the City. I knew the place, I was there some times and I took some photos. But I never heard something about the amazing story of the church. This is so important to know a bit more and I will enjoy my knowledge, -which I get thanks your article-, when I will be next time in London. Hope it is soon possible. I always plan some walks and now I added the church to my ‘City Walk’. Thank you so much and stay safe.

Marvellous, thanks. I always pop in for a few minutes if the doors are open. Lovely description of it in Nairn’s London.

Fascinating, thank you. In the 1980’s I worked in Lombard Street, and on occasion heard the bell strike 9. And it did have a dull sound on the final stroke. So, both an interesting observation by Eliot, and a characteristic metaphor for the start of the working day. At this time when the City is so quiet, perhaps I should check if the sound is the same.

Thanks as always. The interior is in a sad state and needs a lot of money spending on it. There were balconies on the sides which were removed in the 19th century with the fronts being ‘glued’ to the walls. Done I think by Butterfield who should have known better.

It would be wonderful if it could be restored to its former glory as Hawksmoor’s St George’s Bloomsbury has been.

Fascinating information about the faux balconies thank you: I had wondered about these when I visited! Much of the woodwork looks like it is in need of some love and care.

Another great article

Well done

I believe a site Originally of a pagan temple the origin of woolnoth might be attributed to the beam for

Weighing wool at st Mary,s woolchurch which I believe moved Or United with the subject church

Thanks again

David Ayres conservation officer for the ward of cripplegate

Splendid research!

Thank you for an interesting piece, as always. Somewhat confusingly, a plaque marking the site of the old King William Street Station is actually on the side of a building in Monument Street, some distance from St Mary Woolnoth, and this is where I understood the original station entrance to be, although the old ground level building is long demolished. I believe the line then ran below King Arthur Street. One of the rather primitive electric trains that ran on the City and South London Railway can be viewed in the London Transport Museum in Covent Garden

So relevant to the BLM at the moment. So good it wasn`t demolished for the railway. London becoming just another glass and steel city and from a distance so like any other modern city in the world. Great these gems are being preserved.

Over 50 years ago I worked for The London Assurance whose head office was in King William Street opposite St. Mary Woolnoth. I left the City many years ago and have wonderful memories of the church as I organised and sang in a small choir which performed there each Christmas. Two years ago I visited several City churches St. Mary Woolnoth included and was saddened to see the state of disrepair inside however it did give me a wonderful feeling. The post is so relevant to today and once we are able to travel safely again I am going once more to discover more of a Hawksmoor treasure.

Always interesting!

Do we have any further information on Eliot’s “dead sound on the stroke of nine”, which he himself glosses as being “a phenomenon that I have often noticed”? Perhaps there was some defect in the chiming mechanism? Maybe it is still there. I’ve never knowingly heard St Mary Woolnoth striking nine, or any other hour.

I really must drop in there if we ever make it back to working in the office again (I’m about five minutes away when I do go in). Thank you for doing all the research so I don’t have to!

A most interesting article. The church certainly has enjoyed a charmed life, not least when the new ticket hall for London Underground required a great steel ‘umbrella’ covering Bank junction and all approach roads which moved all below it and even damaged Mansion House. I used to encourage guests to sing a little phrase from Amazing Grace to help remind them of the history beneath their feet. The view from the church steps can explain London history from one spot.

Very interesting reading and enllighting.

In 1697, the owner of a coffee house, then at no. 16 Lombard Street, became a sidesman at St Mary Woolnoth. His name is known now in another context, he being Edward Lloyd.

Thank you for a really fascinating account of John Newton, who I knew nothing about before… and his connection to slavery and “Amazing Grace”.

I love this church, but have never explored it properly. It’s now on the ‘to-do’ list when getting about gets more easy.

And I really liked your quotation from “The Wasteland”. The line, “I had not thought death had undone so many” is a reference to Dante’s Inferno, I believe, and I always think of it when walking across London bridge, for some reason!

Thanks for another very interesting piece. I have rung the bells at St Mary Woolnoth though they are not run at present as one of the bells has a crack. If you look at this site you can see more about the bells and hear them ringing. http://london.lovesguide.com/tower.php?id=761

My ancestor, Katherine Barber married Robert Brandon in “St Mary Woolnoth with St. Mary Woolchurch Haw, London” on June 13th 1548. I would love to know what the original church looked like.

Most interesting article. Just one comment; Rev John Newton was Curate-in-charge of Olney Bucks, not churchwarden.

Fascinating to read this article and the comments from other folks. The other images do indeed give good impressions of life in those times.

My great-great-great-grandparents Joseph Rankin and Elizabeth Gleed were also married in this church on 25th May 1794.

Most research about my family refers to this church as St Mary Woolnoth with St Mary Woolchurch Haw and I understand that there were amalgamations of parishes in the 17th and 18th centuries.

However, St Mary Woolchurch Haw was destroyed in the Great Fire of 1666, never rebuilt, and I wonder why that extended name was used. Perhaps that combined name refers to the name of the parish where some of my other relatives were born.

Thank you for this interesting piece. I have been fascinated by this church for some time, since seeing a plate in David Watkin’s English Architecture (and subsequently enjoying descriptions Peter Ackroyd’s novel Hawksmoor), the exterior being so original and unusual. I was fortunate to be able to visit for the first time last week. It was a bright sunny day so the simplicity of the interior was well revealed. For a relatively small church and an awkward site it is remarkably powerful and I feel my experience of it will stay with me.

Hi, Thank you for your article! Very Formative!!

Do you have any information on the architecture of the facade on King William St, now above Starbucks where the ticket office used to be for the railway country. As I am currently trying to find who the Facade belongs to whether the church, the city, or the railway company now TFL for example.