A couple of months ago, I wrote the first post of a series in which I hope I will track down the roughly 170 City of London plaques. The plaques tell a small part of the City’s long history, however due to the limited size of the plaque, they often just provide a name, leaving the viewer to wonder what is actually being commemorated.

For today’s post, I take a look at another five, some of which have plenty of information, others need some digging.

City of London plaques record the churches, Guild and Livery Company Halls, infrastructure, key events and people that have contributed to the City’s history. The majority of people are men, there are very few plaques to women, so to start this week’s wander through the City of London, let me start with:

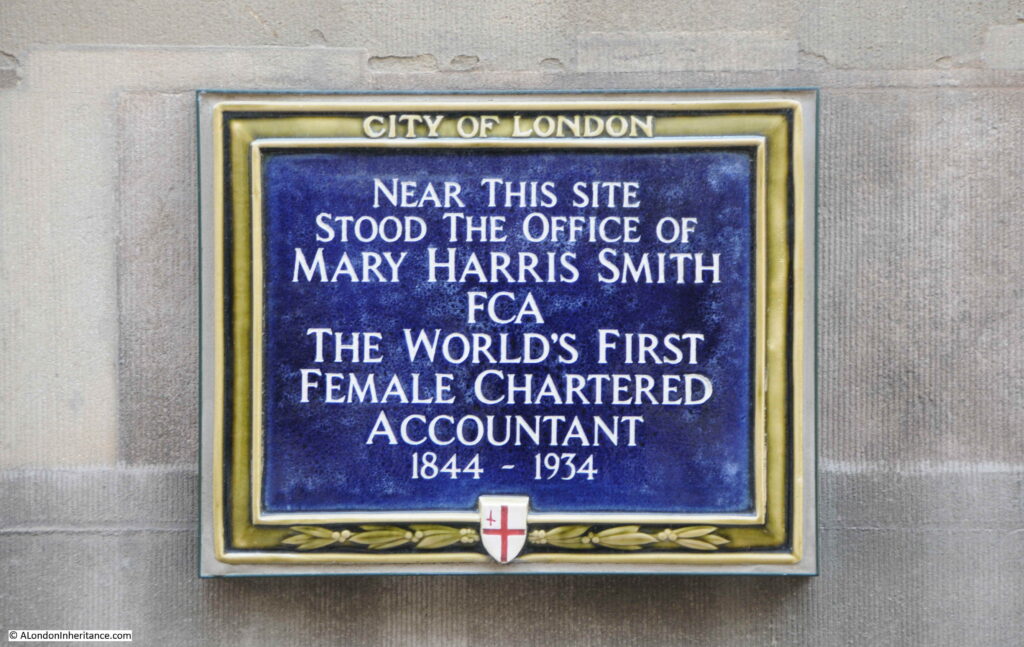

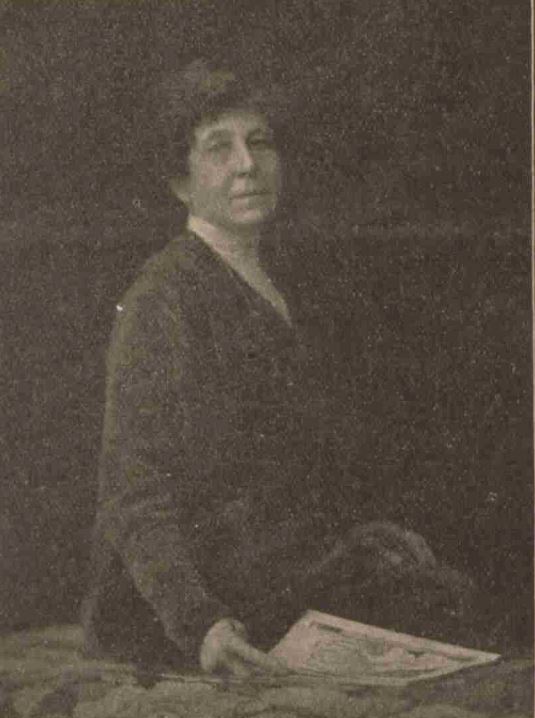

Mary Harris Smith FCA – The Worlds First Female Chartered Accountant

Walk north along Queen Victoria Street, and just before the junction with Poultry and the Bank, you will find number 1 Queen Victoria Street. Walk to the right of this building, along Bucklersbury, and on the side you will see one of the most recent of the City of London plaques. Arrowed in the following photo, as in the shade on a bright day:

This plaque is less than two years old, and was installed on the building in September 2020. It records Mary Harris Smith, the world’s first female Chartered Accountant:

The story of Mary Harris Smith is the story of many women who were struggling to gain recognition in male dominated professions.

Mary Harris Smith had been an accountant for many years, firstly working for a City firm before setting up her own practice in Queen Victoria Street in 1887.

Despite working as an accountant, she was repeatedly refused admission to the accountants professional body, the Institute of Chartered Accountants, either through the route of recognition of her years of work, or through taking the exams set by the Institute.

Whilst there was some support for her admission, the Institute’s solicitor advised the applications committee that the charter only used the male terms of he, him etc. to refer to members, and there was no support to change the charter.

Mary Harris Smith’s persistence eventually worked. She had been seeking the support of other City professionals, members of the Institute and MPs, and in 1919 she was finally admitted to her first professional body, the Incorporated Society of Accountants and Auditors.

The Journal and Express on the 6th of December 1919 recorded the event:

“AFTER 31 YEARS – At a recent meeting of the Council of the Incorporated Society of Accountants and Auditors it was resolved to admit Miss Mary Harris Smith to the Honorary Membership of the Society. Miss Harris Smith has been in public practice in the City of London since the date of the Society’s incorporation and first made application for admission to membership in the year 1886. After 31 years of waiting Miss Harris Smith has seen removed the last obstacle to the admission of women to the Society, and we think there will be general agreement in the profession with the compliment the Council have paid Miss Harris Smith by electing her to Honorary membership”.

Although now a member, the above article refers to her admission as being the “compliment the Council have paid Miss Harris Smith” rather then her right to membership through her ability and years of experience.

A year later, in 1920, she was admitted to the Institute of Chartered Accountants – the event which is commemorated on the plaque.

The Vote newspaper, (subtitled the Organ of the Women’s Freedom League) had been running a series of articles on women in the professions and on the 8th of February 1924 included an article on Women Accountants which featured Mary Harris Smith, who had been elected as a Fellow.

The article also mentions Ethel Watts, who was the first women to pass the Institute of Chartered Accountants exams and gain the ACA qualification:

“The Institute of Chartered Accountants has at present two women members. One of these, Miss Harris Smith, admitted a Fellow of the Institute in May, 1920, was the first woman accountant in public practice before the examination system was started, and has been engaged on highly skilled work for over 30 years.

The other, Miss Ethel Watts, B.A. passed her final examination early this year, and is the first woman to write ‘A.C.A.’ after her name. She served her articles with a Manchester firm, but took her Honours degree at London University. During the war, she became an administrative assistant at the Ministry of Food, and was at one time the private secretary to the Director of Oils and Fats in the Ministry.

She had intended to study law, but her work at the Ministry gave her an interest in business, so she turned to accountancy. In addition to these members, there are 30 women training under articles.”

No idea if there is a plaque to Ethel Watts in Manchester. If not, there should be.

Mary Harris Smith had waited a long time for professional recognition, she was 76 when finally becoming a member. Ill heath forced her to give up work in the late 1920s and she died in 1934.

Mary Harris Smith photographed around the time of her membership of the Institute of Chartered Accountants in 1920:

I can think of only two or three City of London plaques to women, and Mary Harris Smith is a very recent addition – hopefully the first of many more to come.

The next plaque is to one of the many men commemorated across the City:

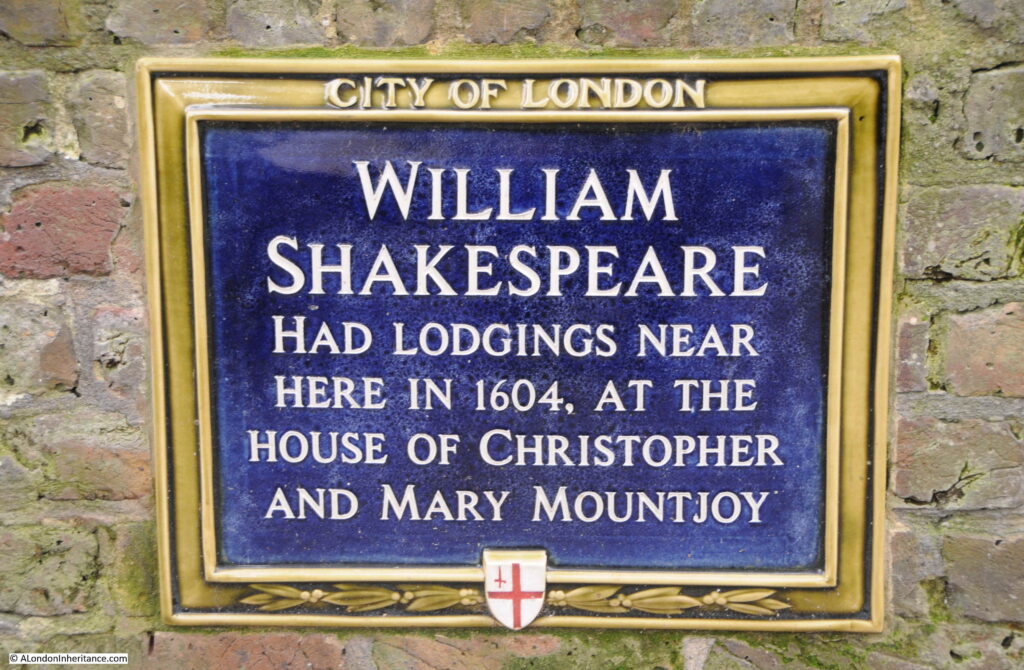

William Shakespeare and the Mountjoy Family.

If you start at the roundabout with the Museum of London in the Centre, and walk a short distance along London Wall, you will come to a small garden which is the site of the church of St Olave, a church that was destroyed in 1666 by the Great Fire.

On one of the low walls in the seating area, there is another of the City of London plaques, highlighted by the arrow:

The plaque records that “William Shakespeare had lodgings near here in 1604, at the house of Christopher and Mary Mountjoy“:

The discovery that William Shakespeare lived for a time at or near London Wall was made in the first decade of the 20th century. A Dr. Charles William Wallace who was Associate Professor of English Language and Literature at the University of Nebraska, had, along with his wife, spent their holidays in records offices searching for references to Shakespeare.

They found one set of documents from a legal case dating from May and June 1612, where Shakespeare had been a witness, and the documents included a very rare signature of Shakespeare.

The Illustrated London News on the 16th of February 1910 carried an article on the discovery, which included the core of the legal case:

“Christopher Montjoy or Mountjoy, a Huguenot refugee, living in Silver Street, with a wife and only child, Mary, carried on there the business of a tiremaker. The occupation would seem to have combined the making of Ladies head-dresses with the work of milliner.

In 1598 Mountjoy took as apprentice one Stephen Bellott, whose mother, a woman of Huguenot family, had married as a second husband an Englishman named Humphrey Fludd. Young Stephen Bellott proved an apt workman, and was much liked by his master and his master’s family.

The daughter, Mary Mountjoy, was attracted by her father’s apprentice, and her parents approved a marriage between the couple. But Stephen Bellott was no ardent wooer, and some pressure had to be brought to bear on him to ‘effect’ a match.

According to the evidence, ‘one Mr. Shakespeare laye in the house’ of the Mountjoy’s when their daughter’s engagement was under discussion. The statement suggests that Shakespeare lodged at the time with the Mountjoy’s, or, at any rate, that he was then staying there. Both parents appealed to Mr. Shakespeare to use his persuasions with the young man.

According to Shakespeare’s evidence, Mrs Mountjoy ‘did sollicitt and entreat’ him ‘to move and perswade’ Stephen Bellott to marry her daughter, and ‘ accordingly he did move and perswade’ him thereunto.

The young man regarded the proposal in a sternly practical light. He asserts that he yielded on specific conditions, namely that the young lady should receive from her father the sum of fifty pounds on her marriage, and the sum of two hundred pounds on her father’s death, together with ‘certaine house-hold stuff’ of substantial value.”

The marriage of Mary and Stephen took place on the 19th of November 1604 in St Olave’s, Silver Street, the site of the plaque.

Mrs Mountjoy died in 1606, and the relationship between Stephen Bellott and his father-in-law became very strained. He claimed that the “household stuff” that Mountjoy had given his daughter was old and worthless, and Mountjoy then denied he had ever made the promises to Bellott.

Bellott then took the case to court, trying to compel his father-in-law to comply with the terms of the alleged contract, and it was because of this that Shakespeare was a witness for the plaintiff.

In his signed deposition, Shakespeare stated that he had known both Mountjoy and Bellott for ten years, that Bellott did “well and honestly behave himself”, and that Mountjoy had promised a “marriage-portion” with his daughter, but he could not remember the amount.

The documents found by Dr. Wallace in the National Archives do not record the outcome of the case, and it seems to have been refered to another authority for judgement.

Dr. Wallace assumed that Shakespeare had lived with the Mountjoy’s from 1598 to 1604, which was the period of Bellott’s apprenticeship, although there is no evidence to confirm this. Dr. Wallace also made a number of claims, including that Shakespeare used the name Mountjoy as the French herald in Henry V from the name of the family he had been living with. Again, there is no evidence to confirm this.

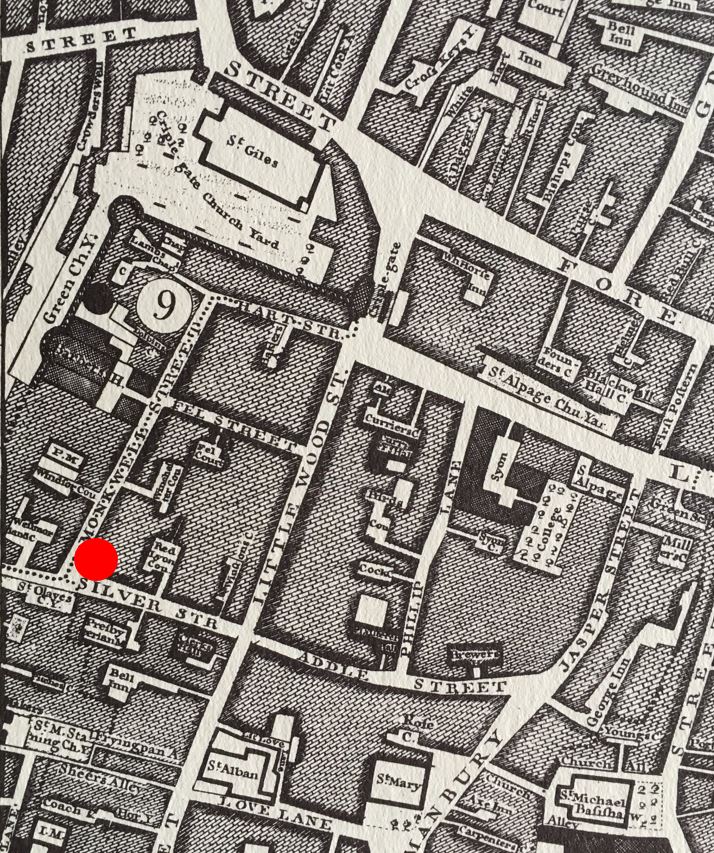

Mountjoy’s house was on the corner of Silver Street and Monkwell Street – two streets that disappeared during the rebuilding of the area following the bombing of the last war. The following map is from Roque’s 1746 map of London, and I have marked the location of the house with a red circle. Just below the red circle is St Olave’s cemetery, the site of the garden we can see today.

The location today of Mountjoy’s house is just slightly north of the location of the plaque, and is probably under the current route of the dual carriageway of London Wall.

A pub, the Coopers Arms was later built on the site of the house and in 1931 it was reported that the Coopers Arms had an old inscription commemorating Shakespeare’s stay.

The Coopers Arms – Silver Street to the right, Monkwell Street disappearing to the left. Strange to think that London Wall now runs through this scene.

Two plaques covering people who have lived or worked in the City. Now for one of the staple of City of London plaques – one of the City’s Guilds or Companies.

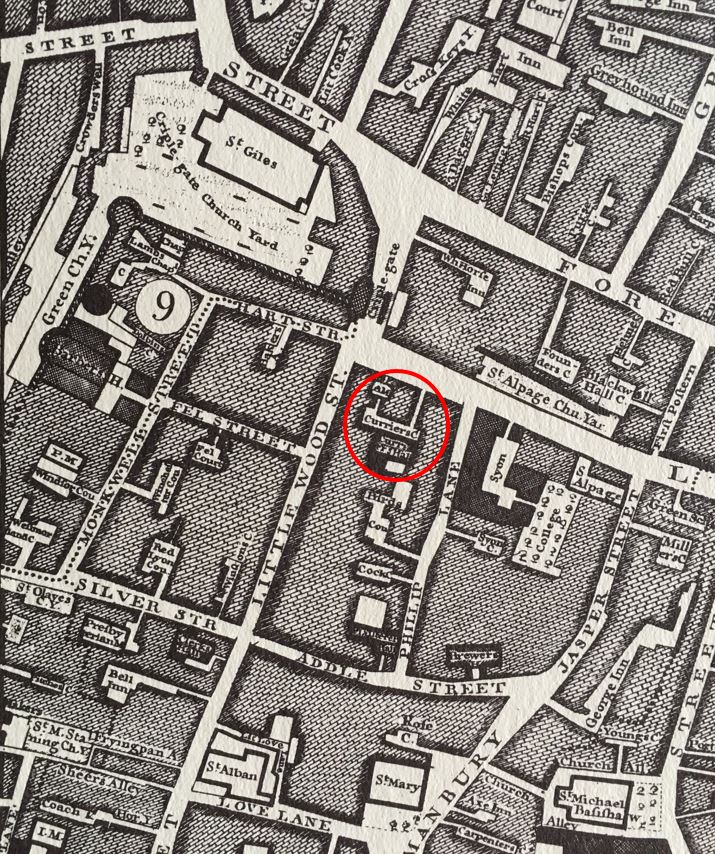

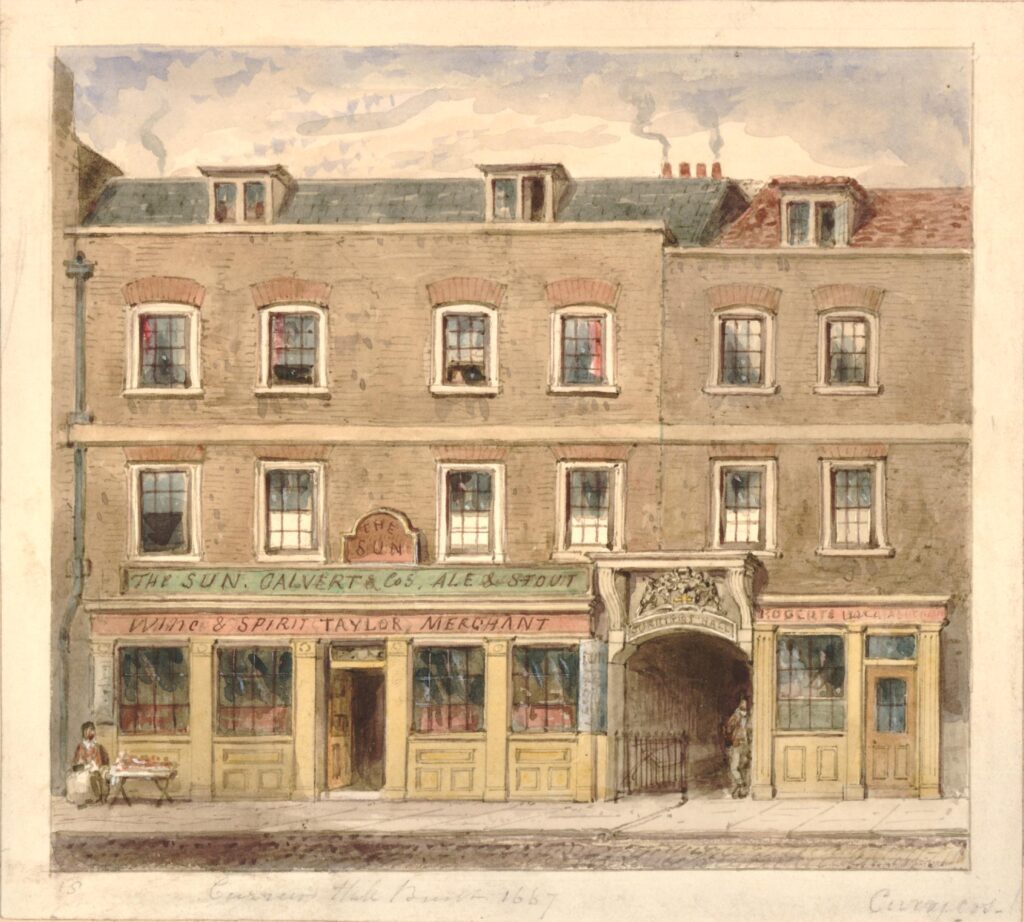

Curriers’ Hall

Not far from the Shakespear / Mountjoy plaque is one to mark the site of Curriers’ Hall. Walk a short distance east along London Wall, up Wood Street, and a short distance along is a pedestrianised walkway to the east, which has some remnants of the City Wall alongside.

Opposite the wall is the goods entrance to one of the new buildings that cover the area, and to the right of the entrance is a City plaque:

The plaque marks the nearby sites of Curriers’ Hall between 1583 and 1940:

A Currier was a leather worker. Currying leather was the process by which tanned skins were stretched and shaved into a fine finish to produce leather which was suitable for the production of leather goods, such as shoes.

The coat of arms of the Curriers’ shows arms rising at the top, with hands holding the tool of the Currier, the shaving knife which was scrapped across a skin, gradually reducing the thickness and producing a smooth finish to the material. The tool is also shown on the shield.

Curriers were originally part of the Cordwainers’ Guild, but an ordnance of 1272 brought about the separation of the professions by requiring that they should have separate working regulations.

Full self governance by the Curriers was achieved through a 1415 ordinance, with an extension of their powers through an Act of 1516, and the grant of a Charter on the 30th of April 1606.

The grant of a Charter was rather late, and was given “by prescription” where a company that had existed for a long time was assumed to have been granted a charter, but which had been lost.

The walkway shown in my photo of the plaque’s location was the original route of the street London Wall (see my post on the history of London Wall).

The location of the plaque is roughly where an entrance to a courtyard in front of the Curriers Hall would have been located.

The same extract from Roque’s 1746 map that I used for the Mountjoy’s house, also shows the location of the Curriers’ Hall, which I have ringed in the map below:

Halls of the City companies were often built back from the street, accessed via an alley from the street, into a courtyard with the hall. I assume this approach separated the hall from the busy street (see also my post on Monkwell Street and Barber Surgeons Hall).

The following print from the mid 1850s shows the alley leading from London Wall to Curriers’ Hall. I assume that the coat of arms of the Company are above the entrance (© The Trustees of the British Museum):

The last version of Curriers Hall was destroyed during the heavy bombing and fires that the area suffered in December 1940.

The Worshipful Company of Curriers still exist today. They do not have a hall, and use the halls of other City companies for their ceremonial events. As with other City companies, they do not have regulatory powers, and today support charitable activities in trades still involved in working leather, or where leather products are used, such as horse riding.

Another City Guild or Company that produced products that would have been used along with those of the Curriers is the:

Loriners’ Trade

Walk along Poultry, towards the Bank junction, and on the right is 1 Poultry. There is an access under the building just before reaching the Bank junction, called Bucklesbury Passage. Underneath the name sign for the passage is a plaque:

Stating “Site of the Loriners’ Trade 11th – 13th Centuries”:

I love the City of London plaques, however they are also rather frustrating. A casual passerby would have no idea what Loriners’ Trade means.

The Loriners were an old City Guild or Mistery, and were granted ordinances in 1260 / 1261 along with their rules of self government.

A Loriner is an example of how specific many of these skilled trades were, as a Loriner was a maker of bridle bits and other examples of metal work used for horses. The Loriner was also a maker of spurs, however spurs became a separate company before joining the Company of Blacksmiths in 1571.

The arms of the Loriners Company show three horse’s bits, along with three black metal bosses:

The plaque in Bucklesbury is unusual in that it is recording where the trade was carried out, rather than the location of a hall.

The Loriners’ did have a hall, which remained until the mid 19th century. The hall was located on London Wall, opposite Basinghall Street (not sure if there is a City plaque at the location of the hall – I need to check). Rocque’s map again is useful in confirming the location of the hall, as shown circled in the following extract:

By the end of the 19th century, the Loriners’ Company had very little involvement with any aspects of the old profession, and it was more a club for social and dining activities. This was common with many other City companies, as this article from the Evening News on the 21st of January 1914 implies:

“They endure, these old guilds, because of the dinner. The Loriners who have very little knowledge of the loriners’s trade. Gold and Wire Drawers who might essay in that delicate little job of drawing gold and silver wires. I know a Citizen and Fishmonger whose lore is not enough to help him in choosing a middle cut of salmon at the stores. Nevertheless, these Loriners and Fishmongers and Wire drawers still flourish, branch and root, dining as their ancestors dined.”

The Worshipful Company of Loriners is still in existence, and still dining, using some of the other City Company halls for their events, but is also involved in a wide range of charitable and educational activities.

My final location in this ramble through a number of the City of London’s plaques is not far away from the Loriners.

Walk through number 1 Poultry to Queen Victoria Street and walk up to the Mansion House, where on the Walbrook corner of the building is a plaque recording the location of:

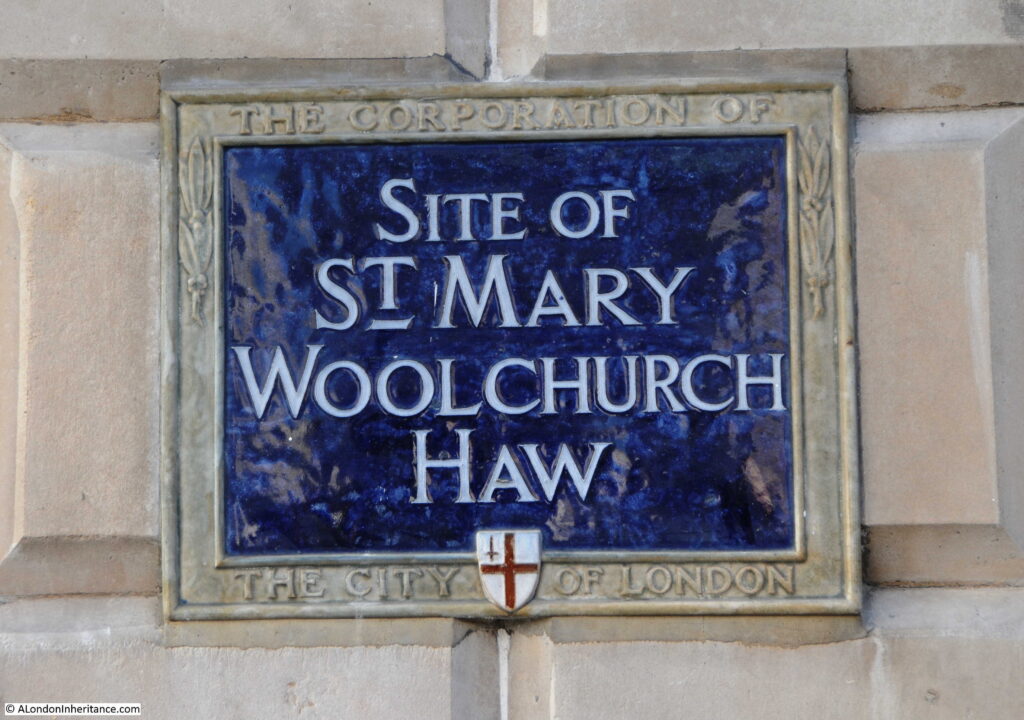

St Mary Woolchurch Haw

Tucked away on the corner of the Mansion House is a plaque, arrowed in the following photo:

Which records that the plaque marks the site of St Mary Woolchurch Haw:

St Mary Woolchurch Haw was one of the City’s churches that was destroyed during the 1666 Great Fire, and not rebuilt. It is remarkable how many churches were in the City before 1666. Many were not rebuilt. A further wave were lost during the late 19th century rebuild of much of the City, and a number were lost and not rebuilt during and after the last war, yet still whenever on a City street we are not far from a church.

The name of St Mary is interesting, but the plaque gives no further information. The dedication is to Mary Woolchurch a name which implies that the church was near to, or had some involvement with wool, but what does Haw mean?

To find out, I referred to the book I use most for learning about pre-1666 City churches – “London Churches Before The Great Fire”, by Wilberforce Jenkinson and published in 1917.

The section on St Mary Woolchurch Haw includes the following:

“St Mary Woolchurch formerly stood near the Stocks Market, which was on the site of the present Mansion House. Stow writes that it was so called ‘of a beam placed in the church yard, which was therefore called Wool Church Haw, of the Troanage, or weighing of Wool there used’

The church was built by Hubert de Ria in the time of William the Conqueror. The first rector whose name is recorded being William de Hynelond, 1349-50. The patronage was partly with the Crown and partly with the Convent of St John the Baptist, Colchester. The church was rebuilt in the 20th year of Henry VI.

John Tireman, rector in 1641, at the commencement of the Civil War was compelled to retire in consequence of his loyalty. john Bull was preacher during the Protectorate, and was afterwards Master of the Temple. The church was not rebuilt after the Fire, but the parish was annexed to that of St Mary Woolnoth”.

So a Haw was a form of beam which was used in the weighing of wool. The Victoria and Albert Museum have a Wool Weight which would have been used with a Haw (Source Link).

The wool weight in the above photo dates from between 1550 and 1600. As can be seen in the photo, the weight has a hole at the top, and through this would have been threaded a leather strap which allowed the weight to be hung on one end of a beam or Haw.

Weights were typically of 7, 14 and 28lbs. The one in the photo is 14lbs.

The beam was pivoted in the middle, with wool suspended at one end, and weights added to the other end of the beam. When the beam balanced, the weight of the wool could be read from the number and weights of the weights used.

The extract from the book mentions that “St Mary Woolchurch formerly stood near the Stocks Market“.

The Stocks Market dates from the 13th century with a charter issued by Edward I. The market was named after the only set of fixed stocks in the City which were used for punishments, such as when William Sperlynge was pilloried in the stocks for trying to sell rotten meat, which was burnt under his nose whilst he was held in the stocks.

The market gradually specialised and by the 15th century it was known as a meat and fish market.

The market was destroyed during the Great Fire of 1666, along with the church of St Mary Woolchurch Haw.

Although the church was not rebuilt, the market was, and expanded to included the land once occupied by the church. It became a general market, which as well as meat and fish, included fruit and vegetables and was one of the major markets of the City.

The following print from 1753 shows the market in operation (© The Trustees of the British Museum):

The church in the background of the above print with the dome and tower is St Stephen Walbrook. The large statue at the front of the Stocks Market is of Charles II, but it has a very interesting history.

The statue originally came from Italy and was an unfinished work showing the King of Poland, John Sobieski on his horse which was trampling on a Turk,

The statue had been brought to London by Sir Robert Vyner who was Lord Mayor of the City in 1675.

A Polish king would make no sense in a City market, and Robert Vyner had the head of the statue replaced with one of Charles II, and the head of the Turk was replaced by one of Oliver Cromwell (or possibly the original head was reworked).

The following side view of the statue gives a better idea of the modified statue. The rider does look like Charles II, however I am not sure whether the person underneath the horse looks like Oliver Cromwell, but this was probably not important. The statue was meant to show the triumph of the Monarchy over the Commonwealth created by the Civil War (© The Trustees of the British Museum).

When the statue was removed, it was given to a descendant of Sir Robert Vyner who apparently relocated it from the City to a family estate in Lincolnshire, from where it was later moved to Newby Hall in North Yorkshire, where the statue that was originally on the site of the Stocks Market, and what is now the Mansion House, can still be seen today:

Image credit / attribution: Chris Heaton / Statue at Newby Hall / CC BY-SA 2.0

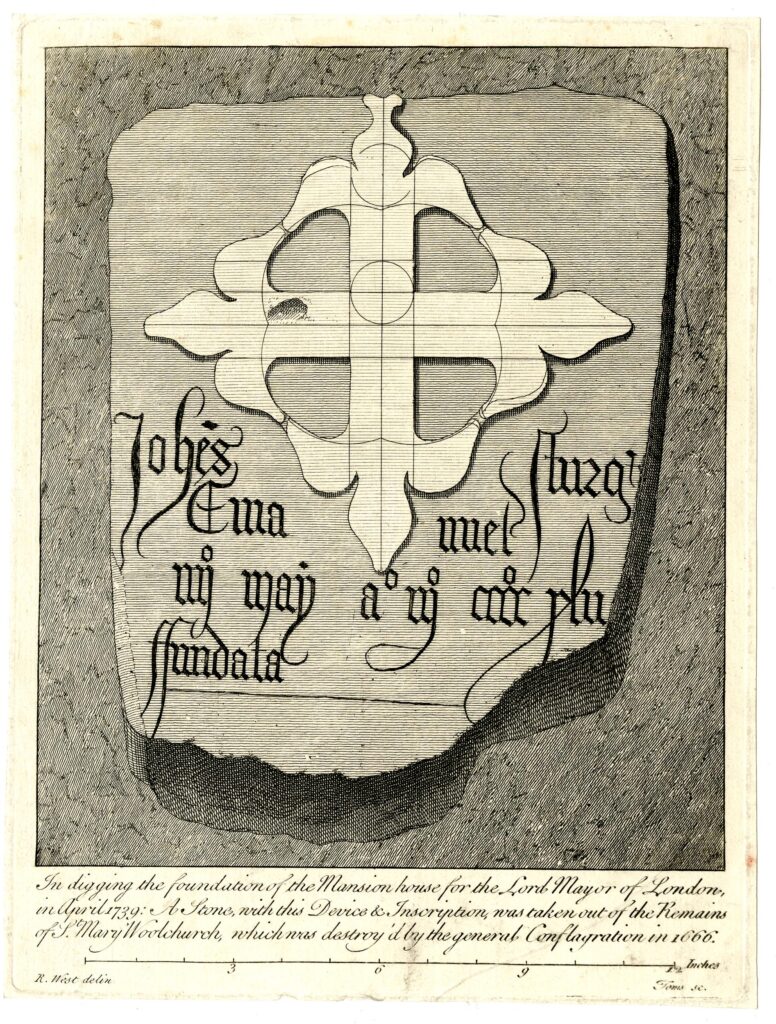

When the Mansion House was built in 1739 on the site of the Stocks Market, a stone believed to have come from the church was found in the new foundations (© The Trustees of the British Museum):

That is five more City of London plaques. They are fascinating as each one, although brief, opens up a whole volume of the City’s long history.

I also find it interesting how bits of London can be found scattered across the country. I have found numerous examples of these, with the statue of Charles II being the latest.

Now that Mary Harris Smith has a recent plaque, I hope that many more of the women who have been a part of the City’s history will also be getting their own plaques in the years to come.

I wonder if the derivation of the term ‘Loriner’ is Hungarian?

The Hungarian word for horse is Ló.

According to the OED, “loriner” or “lorimer” comes from French “lorenier” or “loremier” from Old French “lorain” from Latin “lorum” meaning a strap or thong which forms part of a horse’s harness.

The Hungarian “lo” seems to have a very different derivation.

I shall look for the Sobieski/ Charles II statue when I visit Newby Hall next week! Thank you for another fascinating piece.

“bits of London can be found scattered across the country” reminds me that the original Seven Dials column landed up on the Green in Weybridge, Surrey after it was removed from the vicinity of Covent Garden. The original pillar was installed in 1694, and removed in 1773. The current replica was commissioned in 1984 and installed in1989 by the Seven Dials Trust.

Coincidentally, the two locations are personally close to my heart – (a) where I went to school and (b) where I landed up living for many years. My heart is still in Seven Dials.

It’s a small world.

Thank you for another interesting read. An ancestor of mine, John West, 1641-1723 Scrivener and Benefactor of Christ’s Hospital, London lived and owned property near Stocks Market. I also would love to go and see the statue that once stood there.

The Lodger Shakespeare: His life on Silver Street by Charles Nicholl (2007) is a very readable account of life with the Mountjoys

Readers might be interested to know that Jan Sobieski, the Polish King and leader of the Polish Lithuanian Alliance led the largest ever cavalry charge during the Turkish siege of Vienna and saved the city from the Turks. Today, I believe, that there is an express train from Warsaw to Vienna called the, “Sobieski Express.” In the baggage train of the Turkish Army coffee beans and buns shaped in a half moon were discovered. Both coffee and the buns became popular with the Viennese and Maria Antonette, who was Austrian, introduced the bread buns to French high society after she became Queen of France. They are known now as crossants. There is a Polish vodka called, “Sobieski.” The commander of the Turkish Army was later strangled with a silk cord as was the Turkish custom at the time. The half moon is a symbol of Islam.

The date of the battle outside Vienna was in 1683 and Jan Sobieski was the third Polish King to have his name. The Polish Lithuanian Commonwealth fought with the Holy Roman Emprire in the Battle of Kahlenberg. Croissants not crossants.

Very interesting blog and also readers comments

Love blue plaques and take photos of them wherever I go and am a member on a facebook page. These plaques are lovely and ornate. I even have 2 replicas in my garden of my pet dogs who sadly passed away. Thank you for sharing.