This Sunday, I am continuing with my search for all the plaques commemorating events, people and places in the City of London. The plaques that have been the subject of previous posts can be found on the map at this link.

A mix of very different subjects this week, starting with:

Bethlehem Hospital

On the wall of the old Great Eastern Hotel on Liverpool Street, where the station is also located, is the following plaque marking the site of the first Bethlehem Hospital:

The Bethlehem Hospital (also know as Bethlem or Bedlam) was founded in 1247 when a Sheriff of London, Simon FitzMary donated a parcel of land to the Bishop of Bethlehem.

On this land was founded the Priory of St Mary of Bethlehem. As well as being a religious establishment, the priory also cared for the poor who were sick.

The hospital occupied a space of around 2 acres where Liverpool Street Station now stands. The Historic England record for the hospital states that it was “centred around a courtyard with a chapel in the middle, it had approximately 12 ‘cells’ for patients, a kitchen, staff accommodation and an exercise yard.”

The hospital was taken over by the City of London in 1346, and later in the 14th century and early 15th century, it seems to have gradually changed from being a hospital for the poor, to a hospital that treated “lunatics” – not that any realistic treatment was available.

The term lunatic was a catchall for anyone who had any form of mental illness, and the term would continue to be in use for centuries to come. As an example, in a previous post where I looked at 18th century Bills of Mortality, there were frequent deaths due to “lunatic”, and you were automatically assumed to have this condition if you committed suicide, for example with the following record from January 1716 “Hanged himself (being Lunatick) at St. Olaves Southwark”.

Conditions were harsh at Bethlehem Hospital, and it seems to have been more a place to keep people off the streets rather then to provide treatment, with those in the hospital frequently being restrained and chained.

By the middle of the 17th century, the site was considered too small, run down, and in a very crowded area, so in 1676 the Bethlehem Hospital moved to Moorfields.

The following image uses embedded code, not sure if it will display in the emails. If not, go to the home page of the website.

The image shows “Construction work in the extension to Liverpool Street Station by the Great Eastern Railway, 1894 on the foundations of the first Bethlem Hospital. © Historic England BL12561B”:

The following photo shows the plaque on the side of the building with the street Liverpool Street on the left:

The plaque is a reminder of the harsh treatment of people with conditions of which there was no understanding at the time.

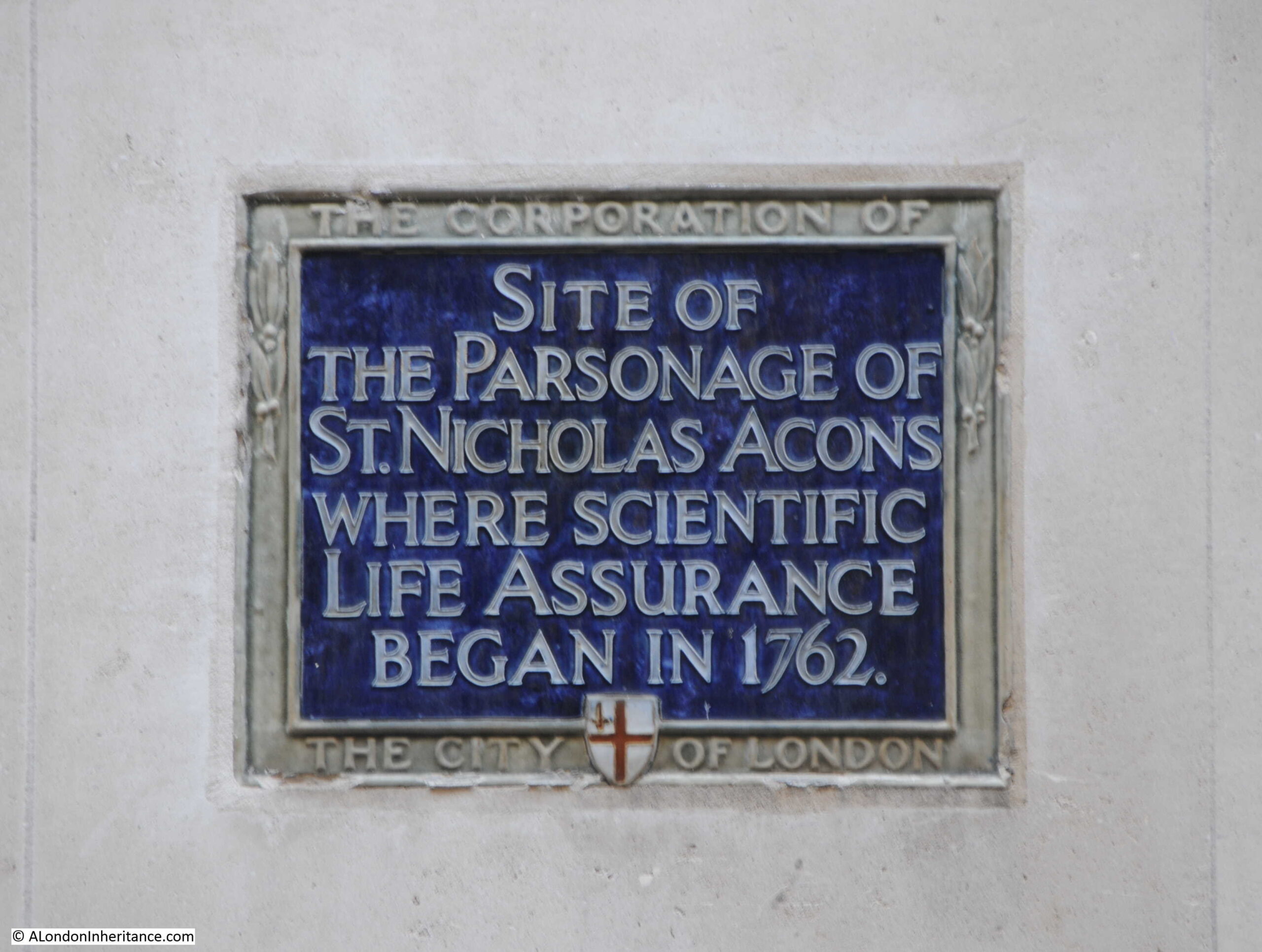

Parsonage of St. Nicholas Acons

In Nicholas Lane in the City of London is a plaque recording that Scientific Life Assurance began at the site in 1762.

Assurance is cover for something that will happen, whilst insurance is for something that may happen, and with life assurance, a payout is inevitable, as along with taxes, the only other certainty in life is death.

However the problem with life assurance is being able to calculate the profile of death in the population being covered. Basically, for how long will people be paying their premiums and when will payout be expected after their death.

Unless this could be fully understood, those offering life assurance ran the risk of making it so expensive that no one would buy the cover, or too cheap and the business running at a loss.

The first company to use a statistical approach to calculating life assurance premiums and payouts was the Society for Equitable Assurances on Lives and Survivorships, which was established in the parsonage of St. Nicholas Acons in 1762.

Work on a statistical approach to mortality had been underway before 1762, with Edmund Halley (after whom the comet is named), having created mortality tables in 1693. A mortality table is basically a table of ages, and for each age a probability is given of death before the next birthday, so for someone aged 45, it would show the probability that they would die before their 46th birthday.

The mathematician James Dodson took Halley’s work further, and although he had died before the founding of the Society for Equitable Assurances on Lives and Survivorships, the society took his work as the basis for their calculations of premiums and payments.

Edward Rowe Mores was instrumental in the use of Dodson’s work, and he was one of the group that founded the company. Mores was a typical 18th century scholar, as his interests ranged from mathematics, typography, history and statistics.

In establishing the company it was Mores who first used the term “actuary” for the person responsible for making the calculations of mortality, premiums and payouts.

The plaque can be seen on the wall in Nicholas Lane, near to Nicholas Passage:

The Society for Equitable Assurances on Lives and Survivorships was known for trying to be fair to its customers, and allocated some of their financial surplus back to their policy holders. The following from the London Evening Standard on the 6th of December, 1851 illustrates their approach:

“Society for Equitable Assurances on Lives and Survivorships, New Bridge-Street, Blackfriars. Instituted 1762.

At the end of every ten years two-thirds of the Surplus Funds of the Society are appropriated to the oldest 5000 Policies, and one-third is reserved as an accumulating fund.

At the last investigation – on the 31st December, 1849 – the Capital of the Society exceeded Eight Millions Sterling, invested in Three per Cents and on Mortgages.

The surplus amounted to £3,215,000, of which £2,113,000 were appropriated to the oldest 5000 Policies, and the remaining £1,102,000 were added to the reserves.”

The Society for Equitable Assurances on Lives and Survivorships eventually became Equitable Life, and the plaque records where the use of statistics were used in financial services, and where the profession of actuary was formalised.

I wrote about Bills of Mortality, and an earlier work by John Gaunt, published in 1676, who took an earlier statistical approach to mortality in my post Bills of Mortality – Death in early 18th Century London.

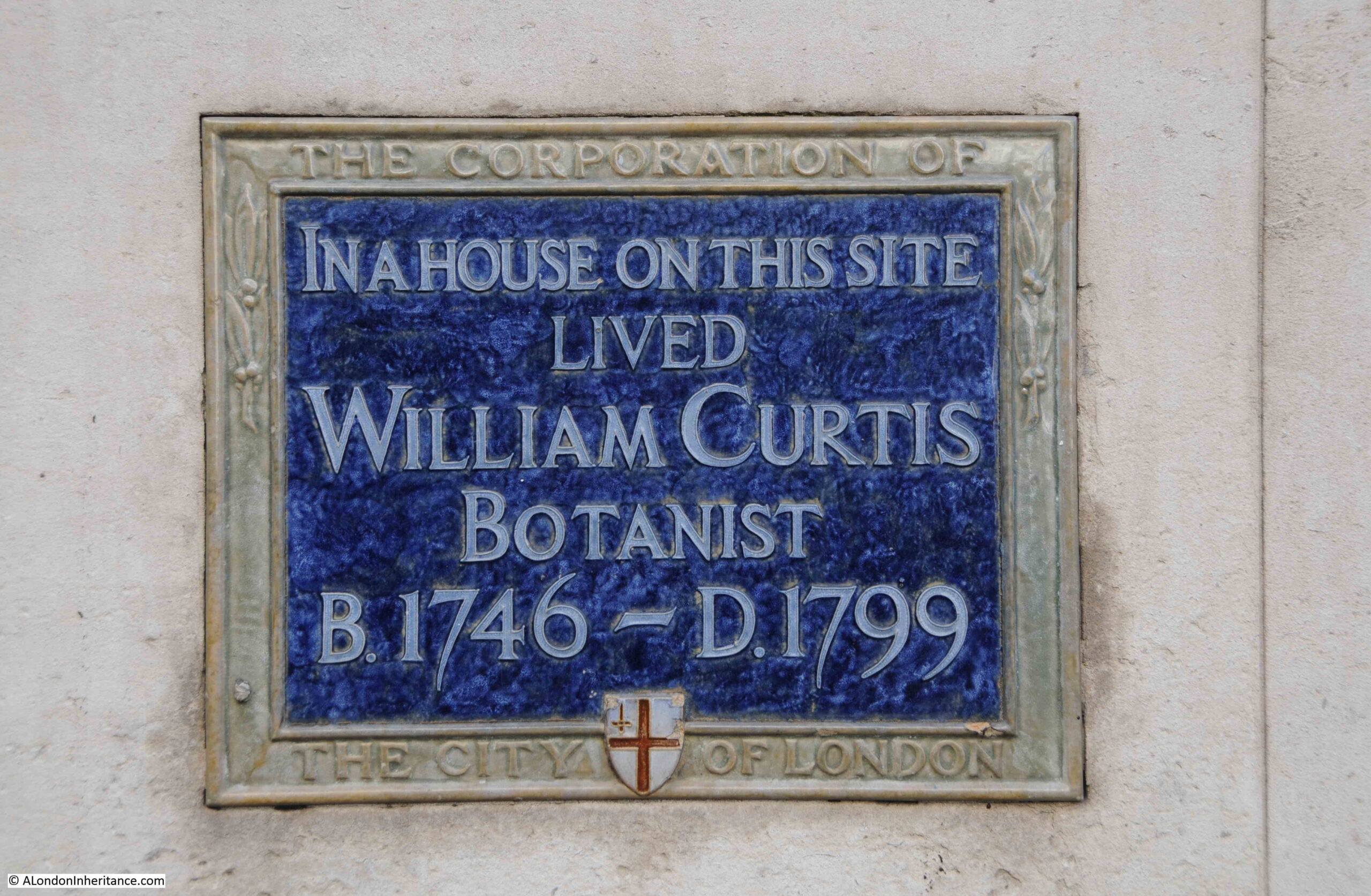

William Curtis, Botanist. Gracechurch Street

In Gracechurch Street there is a plaque recording that the botanist William Curtis lived in a house at the site of the plaque:

It is low down on the wall of a building at the southern end of Gracechurch Street, as can be seen at the bottom left of the following photo:

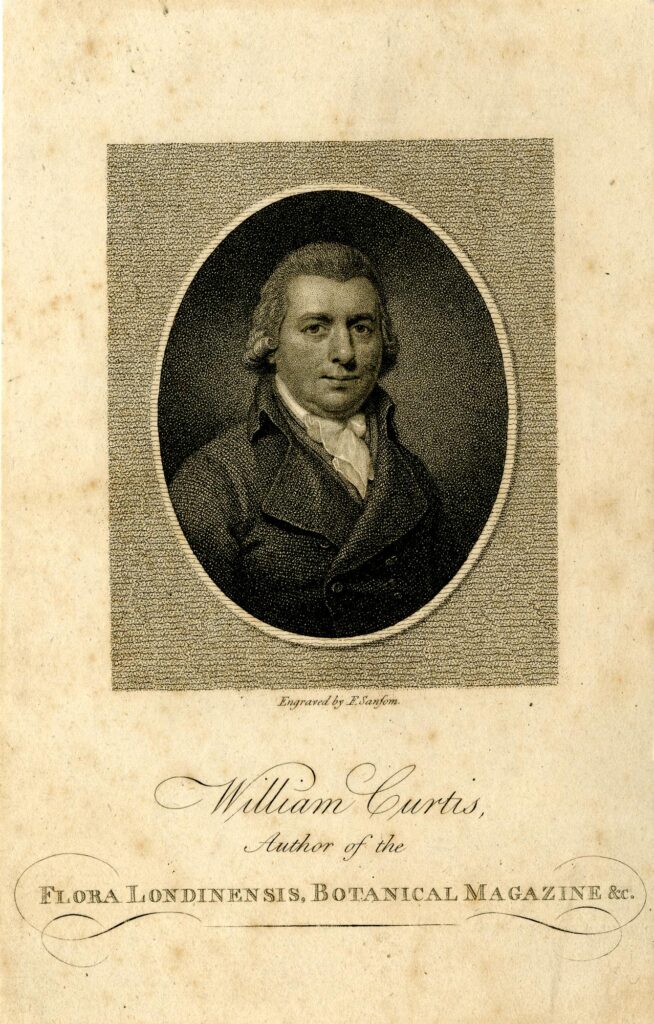

William Curtis was a Quaker, who was born in the town of Alton in Hampshire in 1746. He appears to have had an interest in the study of plants and insects from an early age, and after arriving in London he had a position as a Demonstrator of Botany at the Chelsea Physic Garden (see this post for my visit to the Chelsea garden).

Such was his success that he opened his own garden, the London Botanic Garden in Lambeth, where he is reported to have grown and exhibited in the order of 6,000 plants.

The 18th century was a time when plant collectors were bringing back specimens from across the world. Collectors such as Joseph Banks, who would become President of the Royal Society encouraged the activity.

This influx of foreign specimens did concern William Curtis though, who was worried that they would take over from indigenous species. This led him to publish a set of books that would make his name.

The six volume set was called Flora Londinensis, which had the following full title:

“Flora Londinensis, or, Plates and descriptions of such plants as grow wild in the environs of London : with their places of growth, and times of flowering, their several names according to Linnæus and other authors : with a particular description of each plant in Latin and English : to which are added, their several uses in medicine, agriculture, rural œconomy and other arts.”

The six volumes, published during the last quarter of the 18th century aimed to record all the plants to found within an area of roughly ten miles around London. Each plant was described and illustrated, such as the following example:

The above image is from the Biodiversity heritage Library, where the books are available for download and marked as “not in copyright”.

After publishing Flora Londinensis, William Curtis went on to publish The Botanical Magazine, which contained illustrations and descriptions of various plant species along with other botanical articles.

The magazine continued after his death in 1799 and is still published today by the Royal Botanic Gardens in Kew, as Curtis’s Botanical Magazine, and it is believed to be the oldest botanical magazine in the world, still in publication.

William Curtis:

His magazine made him very financially successful, and along with Flora Londinensis, and his work in London’s gardens, his place was secured in 18th century botanical history, and he is now remembered by the plaque in Gracechurch Street.

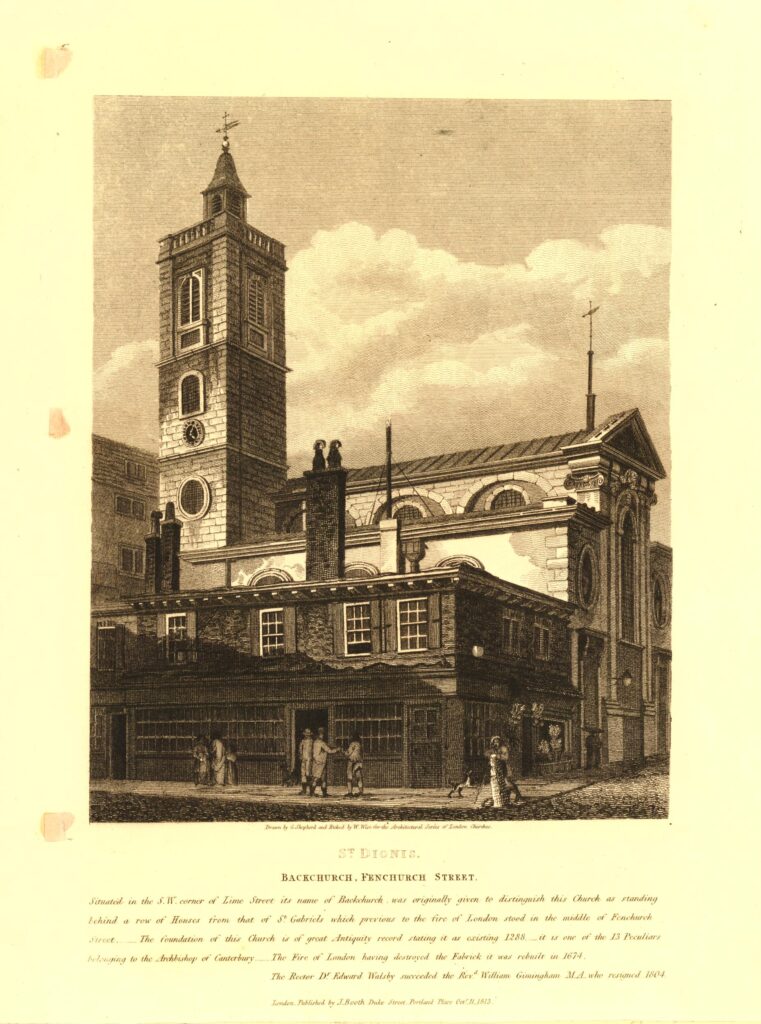

St. Dionis Backchurch

In Lime Street, there is a plaque recording the site of St. Dionis Backchurch:

St Dionis was Dionysus the Areopagite, who was a judge in Athens during the first century AD. He converted to Christianity and was said to have been a follower of St. Paul.

He is the patron saint of France, where he is also known as St. Denis, as a result of having converted the French to Christianity.

In the 1870s there were proposals for the demolition of a number of City churches. The local population was insufficient to justify so many churches, and the aim was to consolidate parishes and congregations.

Newspapers had lengthy articles about some of the churches, and the City Press on Saturday the 16th of September, 1871 had a full column on the history of St. Dionis Backchurch. The following is from the beginning of the article and provides an overview of its history:

“This parish is first mentioned in the records of the Corporation, Letter-book H, folio 105. John Fromond, in 1379, being charged before John Philpot, Lord Mayor, for stealing the dagger or knife called a ‘baselard’ from his girdle, for which charge, it being proven, he, the said John Fromond was adjudged the punishment of the pillory, and then to be banished from the City.

The foundation of the church is of great antiquity; Reginald de Standen was rector in 1283; he was succeeded by Richard Grimston in 1350. The church was newly built early in the reign of Henry VI., 1427-30, John Derby, Alderman, added a fair isle or chapel on the north side, in which he was buried in 1466. Lady Wych, widow of Sir Hugh Wych, who was Mayor of London in 1461, gave some other benefactions; John Bugg also contributed to the new work of restoration. The structure falling into decay, it was partially rebuilt in 1628 – 32, the middle isle of the same being laid in 1628 and a new turret and steeple were added in 1630, and in 1632 new frames were made for the bells. The church was destroyed in the Great Fire of 1666.

It was rebuilt, all but the tower, from the designs of Sir Chistopher Wren, and was finished in 1674; and about ten years afterwards it was found necessary to rebuild the tower, which was done under the direction of the great architect. The building consists of a nave and two aisles formed by Ionic columns, which support the entablature; and arched ceiling in which, under groined openings, small circular lights are introduced on either side. the length of the church is 66 feet, and the breadth about 70 feet; the tower is 90 feet high. At the west end is situated the organ gallery.”

The later half of the 19th century was a time of great change in the City of London. The City was growing rapidly in terms of global influence, trade and finance. Victorian architects wanted to build a City that reflected this, and in 1877 the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings was founded by William Morris to try and preserve many of the buildings at risk, including the church of St. Dionis Backchurch, however in their second annual meeting in 1878, they reported that:

“Amongst the objects the Committee had taken in hand was the preservation of the City churches, and in this respect they were able, to a certain extent, to report favourably, for, although St, Dionis Backchurch had been demolished, the interesting church of St. Mary-at-Hill, Eastcheap, has been saved, in spite of strenuous opposition.”

I wrote about the church of St. Mary-at-Hill in this post. Incredible to think that the church could have been demolished.

The following print of the church, dating from 1813, provides some detail as to the origin of “Backchurch” in the name as “given to distinguish this church as standing behind a row of houses from that of St. Gabriel’s, which previous to the fire of London, stood in the middle of Fenchurch Street” ( © The Trustees of the British Museum):

I wrote about the church of St. Gabriel Fenchurch, in this post. The description of the origins of the name again illustrates how many City churches they were, and how close together.

The plaque can be seen on the wall on the left, in Lime Street, a short distance north of the junction with Fenchurch Street:

As well as the plaque, in the above photo you can see one of the Lime hire bikes across the walkway. This was not how the bike was originally left, and it is interesting how much anger these seem to generate.

I have seen them left in some ridiculous places, blocking pavements, in the middle of the road etc. however whilst I was photographing the plaque, a cyclist arrived at the cycle stand. Saw the Lime bike in the rack, threw it angrily (along with some choice language) out onto the pavement (narrowly missing a pedestrian), putting his own bike in its place, and walking off.

All rather strange.

Crosskey’s Inn

In Gracechurch Street, at the entrance to Bell Inn Yard, is a plaque recording the location of the Crosskeys Inn:

In the 16th century City of London, there were four main locations where plays were performed. These were the Bell Savage off Ludgate Hill, the Bell at Bell Inn Yard (the location of the above plaque), the Bull off Bishopsgate Street, and the Crosskeys Inn.

Inn’s were perfect locations for the performance of plays. They frequently had a large yard which was normally used for the arrival and departure of coaches and wagons, but could also provide the space for actors and an audience.

They were places were people could congregate, and the Inns benefited from the sale of food and drink before, during and after a performance.

There has been some research that suggests that the Crosskeys were one of the few locations that put on plays inside rather than in the yard, however this is difficult to confirm.

Actors of the time were frequently grouped in a company that was financed by a wealthy sponsor, and the company took on the name of sponsor.

At the Crosskeys Inn, Lord Strange’s Men performed in 1589, when William Shakespeare may have been with the company. Lord Strange was Ferdinando Stanley, the 5th Earl of Derby, and after Stanley’s father died, and he became the Earl of Derby, they became known as the Earl of Derby’s Men.

The Lord Chamberlain’s Men are also believed to have played at the Crosskeys Inn in 1594.

The use of these inns for performances seems to have ended around 1593 and 1594, when they were banned following an appeal by the Lord Mayor to the Privy Council. This is believed to have been due to an increase in the plaque, and they moved out of the City to the Theatre in Shoreditch and the Globe on the south bank of the river.

It may also have been due to the rowdy behaviour that sometimes accompanied a play, which the City may well not have appreciated within their boundaries.

The Crosskeys Inn continued in use during the 17th century, until it was destroyed during the Great Fire of 1666.

What is confusing is why the plaque to the Crosskeys Inn is at the entrance to Bell Inn Yard.

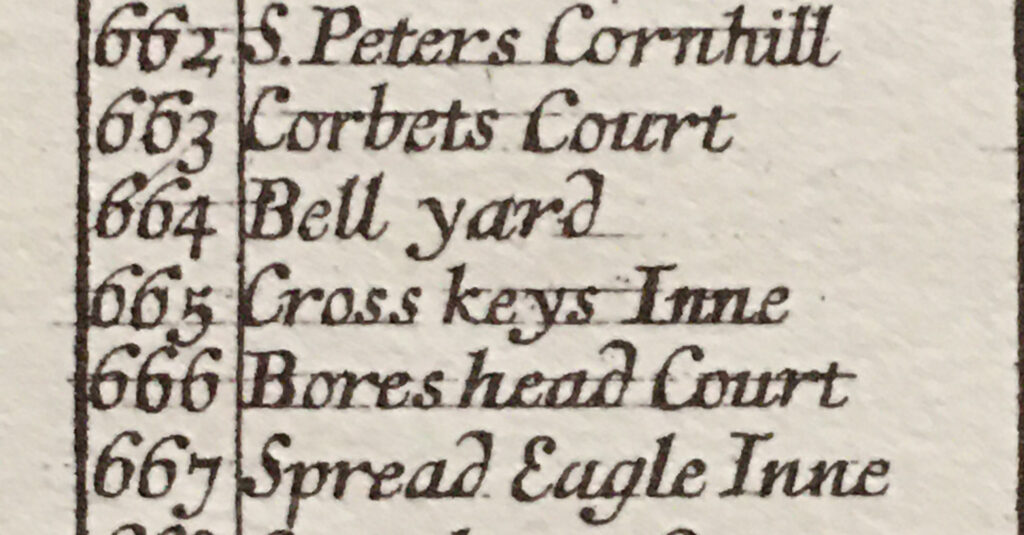

Morgan’s map of London from 1682 shows the location of the inn (the inn was rebuilt after the fire).

In the following map, the red circle is around the location of the Crosskeys Inn and the yellow circle around Bell Yard:

The key to Morgan’s map includes the number and location:

I have checked a number of maps, and tried to accurately align them along Gracechurch Street, and as far as I can tell, the Crosskeys Inn was located along the current Bell Inn Yard, and Bell Yard was just a bit further north and has been lost under the larger buildings that now line the west of the street.

The Crosskeys Inn was rebuilt after the Great Fire, and continued as one of the City’s busy coaching Inns. The name appears on Rocque’s map of 1746, and there are numerous newspaper reports referencing the inn.

It appears to have closed in 1850 and been demolished soon after. There is a newspaper report in the Illustrated London news on the 24th of May 1851, which referring to Gracechurch Street states:

“On the west side of that thoroughfare, and on the site of the old Cross Keys, an Inn from which the licence was withdrawn some twelve months ago”.

The newspaper report was about the collapse of a building which was under construction and covered a wide area along Gracechurch Street, including the site of the Crosskeys Inn.

The building using a frame of iron girders, collapsed when one of the girders snapped. There were around 80 workmen on the building, with many injured and 3 deaths.

So the plaque refers to the version of the Crosskeys that was part used for putting on plays in the later part of the 16th century. The inn was rebuilt and continued in use as a coaching inn to the mid 19th century.

The name Crosskeys comes from the arms of the papacy, where the crossed keys are St. Peter’s keys, and the keys to heaven.

Attribution: Coat of arms of the Holy See, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

And there is now a Wetherspoons on this part of Gracechurch Street called the Crosse Keys. It is in the former premises of the Hong Kong & Shanghai Banking Corporation, which was designed by W. Campbell Jones and dates from 1913.

It has a rather splendid interior and is well worth a look.

That is about 25 of the roughly 170 plaques within the City of London covered, so still a number to go.

Another brilliant post. Despite being one of the first City Guides, I have learnt so much from your blogs and look forward to them continuing ad infinitum. I hope you are rewarded by being given Freedom of the City! All good wishes,

I am confused I was of the opinion that the name cross keys when used in the name of an inn was a reference to its location at a crossroads particularly when in use as a coaching inn for the refreshment of horses and passengers alike, particularly in the 18th and 19th centuries before the wider establishment of the railways.

These posts of yours I find very interesting although never a resident I frequently visited the city particularly after meeting the lady who was to become my wife. She living in ealing w5 and working at Coutts bank in the strand. I used to enjoy my own walks of discovery over time until marriage and carrier moved us north.

While you are right in the distinction you make between Assurance (limited to policies on human life) and insurance (policies covering all other risks), being based on the certainty of a payment being made on the policy, the original distinction has become lost. Today the word assurance is used for all life policies, including those for a fixed term, eg. 10 years, (“term assurance”) where there is no certainty of a claim being made which should properly be called insurance.

So fascinating, thank you. I save your posts to enjoy on Monday at my desk – they’re a bright point at the start of my working week. I’m so stoked that there are so many dozens more of these plaques that you’ll be working your way through and using as starting points to tell us more about their locations and history. I’ve always been a West End boy and still work and socialise in W1 – but since I moved to Borough ten years ago and particularly when I took up running during lockdown, I’ve started to enjoy ferreting around the history of the square mile (and the wider area), just across the river from me. It’s – I think I can properly use the word ‘literally’ – an endless source of interest and I’m hugely grateful that you’re doing this legwork and research work for your readers. Please do keep it up! And thank you!

“This is believed to have been due to an increase in the plaque, ” I assume you mean plague