The next stage of the journey from the City of London to the Sea is from Greenwich to Barking Creek. This stretch of the river has lost a considerable amount of industrial and dock activity over the last 50 years. On the south bank of the river, the Greenwich Peninsula is the location of the Millennium Dome or as it is now called, the O2 Arena which, until recent years, was the only significant redevelopment on this stretch of the river, however the race to develop riverside apartment buildings is now extending down river from Greenwich.

The north bank has seen development along the Isle of Dogs with both residential and office buildings running up to Blackwall.

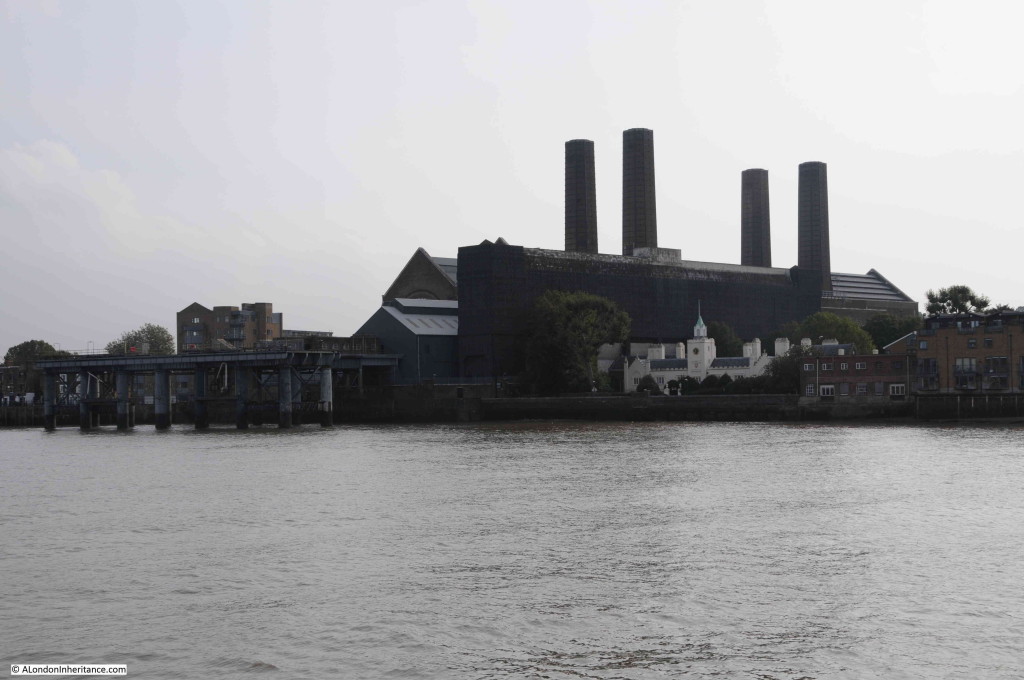

After leaving the Cutty Sark and the old Royal Naval College behind, there is an industrial intruder. The Greenwich Power Station was built between 1902 and 1910 to provide power (along with the Lots Road power station in Chelsea) for the London Tram and Underground networks. London Underground switched to the National Grid for power in 1998 since when Greenwich Power Station has held the role of a provider of emergency power to the London Underground. Initially coal fired, with the coal being delivered to the jetties on the river, the power station is now oil fired. There are plans to install new gas powered generators so the power station will remain a landmark on the Greenwich river bank for decades to come.

The white building in the shadow of the power station to the right, is the Grade 2 listed Trinity Hospital. Built between 1613 and 1617 with later additions and alterations (mainly from 1812), the building of these almshouses was funded by Henry Howard, Earl of Northampton.

Although not a member, the Earl of Northampton entrusted the management of the almshouses to the Mercers Company, who continue running the charity responsible for the almshouses to this day.

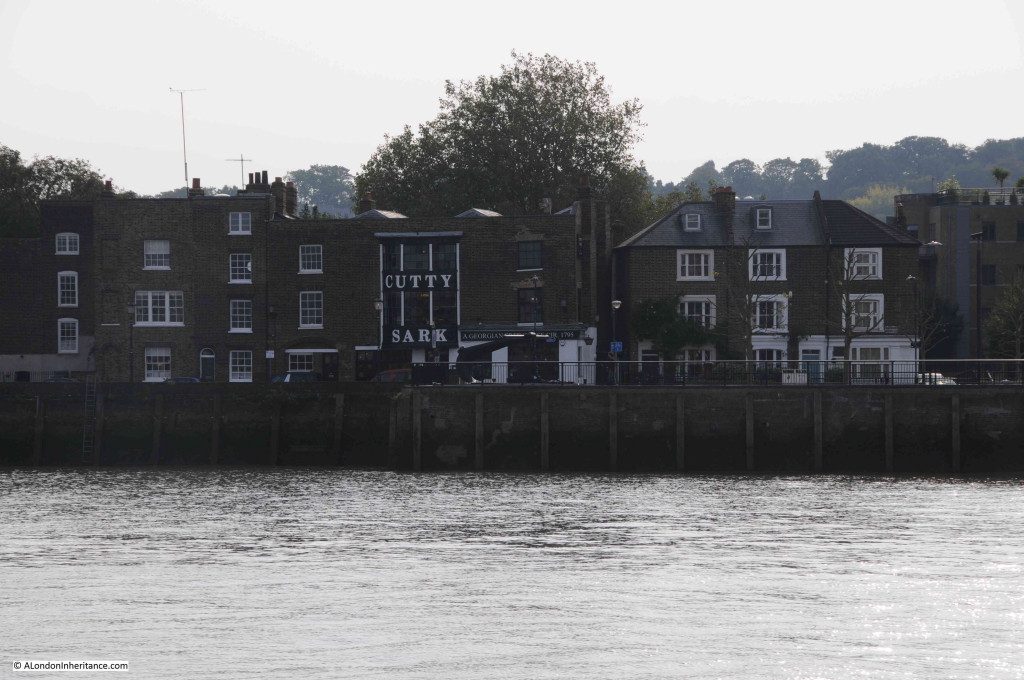

A short walk along the Thames from Greenwich Power Station is the Cutty Sark pub, a perfect place to sit outside and watch the river.

A short distance along the Greenwich Peninsula is Enderby’s Wharf, the latest housing development which I suspect will soon be replicated all the way to the O2. Enderby’s Wharf has an important industrial heritage. The wharf takes the name from Samual Enderby & Sons, a whaling company who developed the site. It was later the site of the company Glass, Elliot & Co, who built submarine cables at the site which were loaded onto cable ships from the wharf.

Part of the original equipment that carried cable from the factory, across to be loaded on the ships moored at the wharf remains at the site and can be seen in the photo below in front of the yellow crane.

Adjacent to Enderby Wharf is Morden Wharf, having been acquired by developers in 2012, it is a site that will also soon be redeveloped. I believe the name comes from the original owners of parcels of land along this stretch of the river, Morden College, who also owned part of Enderby Wharf.

I doubt you have ever wondered where the Thames tourist boats are taken for maintenance, but if you did, it is here, slightly further along from Morden Wharf. A rather novel form of dry dock for lifting the boats out of the water for servicing below the water line.

Almost reaching the northerly point of the Greenwich Peninsula the Millennium Dome / O2 Arena comes into view. After a rather controversial opening and original purpose, this is now a successful entertainment venue and is an interesting architectural structure, unique in London, however I have no idea what the building on the left adds to the area. Another recent building in London that looks bland and in the wrong location.

Rounding the northern end of the peninsula and the Emirates Air Line, or more commonly known as the Dangleway, comes into view. Opened in 2012 and operated by Transport for London, the route connects the Greenwich Peninsula with the Royal Victoria Dock area, close to the Excel exhibition centre.

On the north bank of the river is the original Trinity Buoy Wharf. Trinity House built their workshops here in 1803. The site was used for the construction and storage of buoys and provided moorings for the Trinity House ships that would collect and lay the buoys along the river and out to sea, from Southwold in Suffolk to Dungeness in Kent.

The site included extensive workshops and storage facilities including experimental lighthouses, the last to be built can still be seen today.

The site closed in 1988 and now hosts a range of facilities including rehearsal rooms, studio and gallery space.

Bow Creek is just to the right of the red lightship in the photo below and is where the River Lea enters the Thames at the end of its journey from the source at Leagrave, just north west of Luton.

It is good to see that there is still some manufacturing remaining on the banks of the river. Nuplex is a global company based in Australia and New Zealand manufacturing resins which are used in a wide variety of industrial coatings. The North Woolwich / Silvertown site is their UK manufacturing and service centre.

It is good to see that there is still some manufacturing remaining on the banks of the river. Nuplex is a global company based in Australia and New Zealand manufacturing resins which are used in a wide variety of industrial coatings. The North Woolwich / Silvertown site is their UK manufacturing and service centre.

The cranes in the background are along the old docks close to the Excel exhibition centre. Left in place to provide a reminder of how the area would have appeared prior to the closure of the docks.

On the north bank, adjacent to the old Royal Victoria Dock is the Millennium Mills building. A major flour milling operation throughout much of the 20th century. The “D” Grain Silo, the building in white on the right is a Grade 2 listed building.

This whole area, including the Millennium Mills is about to undergo redevelopment, although the Millennium Mills building will remain.

Looking back to the O2 and Canary Wharf with one of the Thames Clippers passing. The Thames today is very quiet, most of the time, only the occasional passenger or tourist boat to be seen.

The function of the river is now changing. For many centuries it brought goods to and from the docks and factories that lined the banks of the river. Now it is a relatively quiet waterway providing a scenic location for the new developments lining the river that are gradually moving downstream.

We now come to the Thames Barrier. The flooding along the Thames following the storm surge of 1953 resulted in a new strategy for how the land along the river could be protected from such serious flooding. Continually building higher and higher walls alongside the river would not be practical, for example without the Thames Barrier and to protect central London from the most serious storm surges, the walls along the Embankment would have to be many feet higher, to the top of the Victorian street lights, almost shutting of the view of the river from the walkways alongside.

The Thames Barrier provides two main functions, it prevents storm surges from reaching further up the river, and following periods of very heavy rain, it can prevent a high tide from moving up river thereby providing a space for the flood water moving downstream to occupy, before passing through the barrier at the next low tide.

The Thames Barrier and Flood Protection Act 1972 led to the construction of the barrier which became operational in 1982.

A walk along the Thames during a very high tide will demonstrate how essential the Thames Barrier is to the protection of London.

About to pass through the Thames Barrier:

About to pass through the Thames Barrier:

When I first had a trip down the river in 1978, construction of the Thames Barrier was well underway. The following are three of my photos from the time showing this major engineering project. Although similar, and larger, barriers had been constructed in the Netherlands, which had also suffered very badly in 1953, this was the first project of this type in the UK.

And what passing through the Thames Barrier looks like today.

Along this part of the river, the bank is lined with many relics of the river’s industrial past.

The Tate & Lyle sugar refinery in Silvertown is still in full operation despite recent problems with EU imposed taxes on imported sugar cane from outside the EU which is used by the Silvertown plant rather than sugar beet produced within the EU,

Delivery of the raw product to be processed is by ship to the sites’ own mooring where the cranes lift out the sugar cane into the two black hoppers for transport to the refinery.

Delivery by ship makes the Tate & Lyle sugar refinery the furthest point upstream for large commercial shipping.

Here is the old North Woolwich Pier. Before the free Woolwich Ferry came into operation, the Great Eastern Railway ran a passenger ferry across the river from this point. The brick building behind the pier is the old terminus building of the Great Eastern Railway.

Looking back towards the Woolwich Ferry. The two ferry terminal buildings on either side of the river. One of the ferries at the Woolwich terminal and two ferries moored in the background.

Passing North Woolwich, on the north bank of the river we now come to the old entrances to the Royal Docks. These were the last major docks to be built this far up the river and had the largest capacity of all the London docks at the time. The first, the Victoria Dock was opened in 1855, with the last, the King George V Dock opening in 1921. It was at this time that the cluster of docks (including the Royal Albert Dock which was opened in 1880) were given the name Royal Docks.

The Docks prospered until the growth of containerisation and in the size of ships meant that there was insufficient business for the docks and they finally closed in 1981.

Here we pass the original entrance to the King George V Dock.

And thanks to the Britain from Above web site we can see what this entrance looked like in 1946. The King George V Dock is to the left and the Royal Albert Dock is to the right. The land in-between the two docks is now occupied by London City Airport which opened in 1987. I flew from the airport a number of times in the late 1980s and it was remarkably fast and informal. On the planes (relatively small, propeller driven Dash 7s), the pilots would often leave their door open and if you could get the right seat you had a superb view of the London Docks on arrival and departure.

Next along is one of the two entrances to the basin that led in to the Royal Albert Dock. The channel leading from the river to the basin from this entrance has been completely filled in, with the entrance on the river providing a reminder that this was an entrance to one of the largest docks on the River Thames.

The other entrance to the basin that led to the Royal Albert Dock is still in existence and provides access to the Gallions Point Marina, which now occupies the basin between the river and the Royal Albert Dock.

Next along are the remains of what was once a very major industrial complex.

The Gas Light and Coke Company opened a plant here in 1870 to produce coal gas (along with a range of by-products) from coal. The site was chosen due to the large expanse of land and the deep water berthing available on the river for the colliers that would transport the coal to be processed.

The site supplied gas (or town gas as it was also called) for much of London north of the Thames. The discovery of large supplies of natural gas in the North Sea in the 1960s meant an end to town gas and the plant closed in 1970.

Only one of the many gas holders survives and can be seen to the left in the photo below. This is Number 8 gas holder, built between 1876 and 1879, the gas holder is 59m in diameter and was capable of holding 56,600 cubic meters of gas.

The piers in the river are all that remain of the large moorings on which the colliers would moor to unload their cargos of coal ready for processing into gas for the rest of London.

Further along are a second set of piers for another mooring.

The size of the site can be seen in the following photo from the Britain from Above web site, taken in 1931. The first set of piers on the photos above support the mooring to the left of the photo below, whilst the second photo are the moorings to the right.

The name for the area, Beckton, comes from the name of the Governor of the Gas Light and Coke Company at the time the plant was opened, Simon Adams Beck.

And so to the final point in the tour down the Thames for this post, Barking Creek.

Barking Creek is where the River Roding (which rises near Stansted Airport) reaches the Thames. The area nearest the river was also affected by the floods of 1953. The residents of Creekmouth, which is directly to the right of the entrance, had more than 3ft of water invade their homes.

Being downstream of the Thames Barrier, the creek requires its own protection and this is provided by the barrier shown in the photo below. The main barrier provides sufficient clearance to allow shipping to enter the creek and descends when there is a risk of flood water entering the creek.

That completes the Greenwich to Barking Creek stage of my exploration of the River Thames from City to Sea. Again, far too much history to cover, however I hope this has provided an introduction to this section of London’s river.

In my next post I will follow the Thames from Barking Creek to Southend.