Back in August 2015 I published some of my father’s photos where I needed help with identifying the location. This week’s post is about one of these locations, which I really should have known, however thanks to many readers it was quickly identified. The following photo was taken in Glamis Road in Wapping, looking towards the Prospect of Whitby pub which is framed by the bridge crossing the entrance to the Shadwell Basin from the River Thames.

The same view today is shown in the photo below. My father was much better at timing photos. When I took the photo below, it was a lovely sunny autumn day, but this meant I was looking into the sun so the lighting is not ideal to bring out the detail. Converting to black and white and adjusting the contrast did help slightly.

Glamis Road crosses the bridge to become Wapping Wall which passes the pub and then meets Garnett Street and Wapping High Street. The area was dominated by the London Docks which were still in operation when my father took the above photo in 1951. As can be seen in the 1951 photo there is still the control cabin for the bridge on the left and directly in front of the bridge on the pavement on the left looks to be some form of illuminated sign which perhaps was the warning sign when the bridge was about to open.

Today’s photo has one of my pet hates – the amount of clutter we have across the streets. Multiple poles with multiple signs. Not sure how long the new road layout has been in place, but I have seen these in place for years after the original change.

The bridge is across the eastern entry from the River Thames to Shadwell Basin which was the eastern end of the London Docks complex.

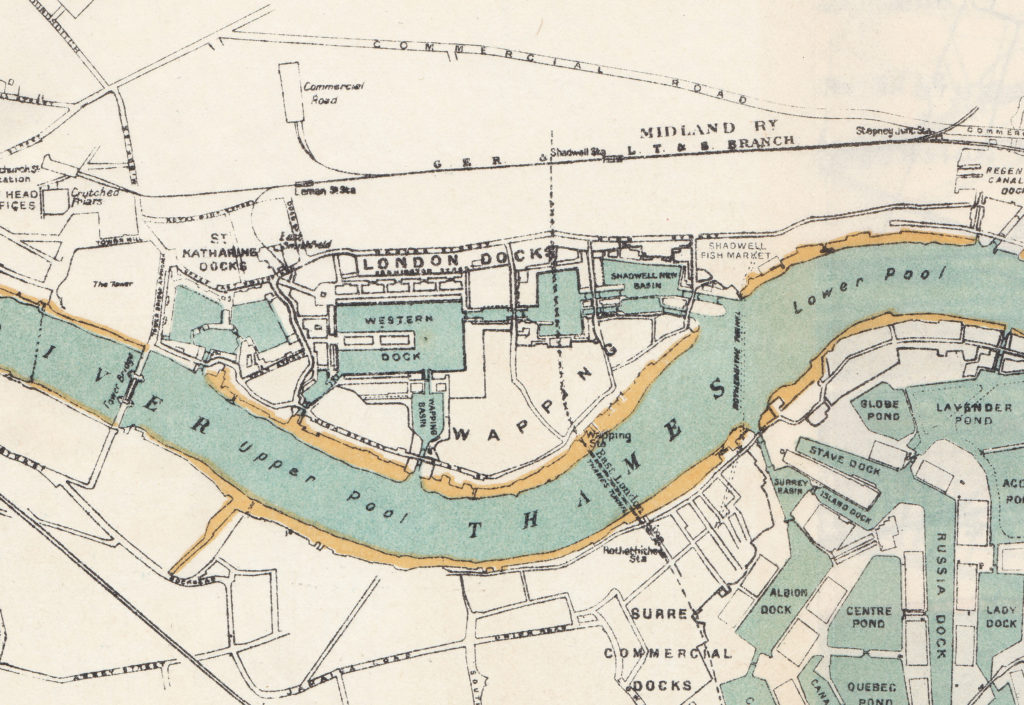

The map below shows the 19th century configuration of the London Docks and shows how much of Wapping these docks occupied at their fullest extent. Look at Shadwell Basin on the right of the London Docks and there are two channels providing access to and from the Thames. The only one of these channels still in existence is the upper channel and it is this channel that the bridge crosses.

The original part of the London Docks, the Western Docks opened in 1805 and specialised in wine, brandy, tobacco and rice. The docks were a success and over the next couple of decades expanded further east with the Shadwell Basin and eastern entry into the river being the completion of the London Docks complex.

The land on which the Shadwell Basin was built was originally the home of the Shadwell Waterworks Company which had commenced operation in 1669 to provide a water supply to the area east of the Tower of London. Soon after the opening of the Western Docks, the London Dock Company purchased the land and the Shadwell Waterworks Company which maintained operation until water supply was transferred to the East London Waterworks, which then allowed the Shadwell Basin to be built.

If you look above the two channels, the area that is now occupied by the King Edward VII Memorial Park was original the Shadwell Fish Market.

The London Docks closed in 1969 and over the following decades the majority of the docks were filled in. The Shadwell Basin is the only main dock section to survive.

The following photo is looking into Shadwell Basin today. The land on the left is between what was the two channels to the river and was Brussels Wharf, and was occupied by a large shed as can be seen in my father’s photo.

Looking from the bridge along the channel which leads to the Thames. At the end of the channel were the lock gates needed to protect the water level in the docks from the variations of the tidal river. It must have been quite a sight to see the shipping pass through here in the hours when the tide was right, particularly during the days of sail when entry to such a narrow dock entrance was down to mastering the flow of the river and wind. The entrance today is permanently blocked.

Last year, during my trip down the river in the Paddle Steamer Waverley I took the following photo from the river showing the entrance to Shadwell Basin. The bridge can just be seen above the entrance.

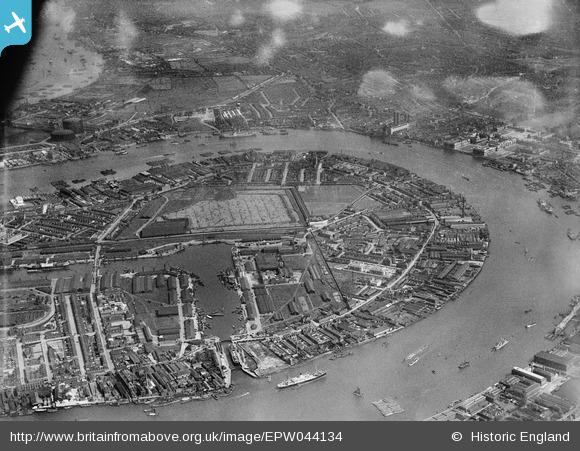

The Aerofilms archive provides the perspective needed to understand the layout of the docks. The following photo was taken on the 17th June 1948. Wapping is the land in the lower part of the photo with the Shadwell Basin in the lower centre with the entrance to the river leading to the left. The bridge can be seen with the road running up to where it bends to the right past the Prospect of Whitby.

If you look to the right of Shadwell Basin, there is a channel that leads into the next section of the London Docks on the right. There is a similar bridge over the channel, which is still in existence. This is in Garnet Street.

Back to the original wall and signage on the wall records the names of the Shadwell Basin and Brussels Wharf.

View from the other side of the bridge showing the large counterweight used to balance the road span as the bridge is raised or lowered.

Always on the lookout for murals, I was pleased to see this within a shelter adjacent to the bridge.

At the far end of my father’s original photo was the Prospect of Whitby which claims to be London’s oldest riverside pub dating from around 1520. The pub was originally called The Pelican and the alley and stairs down to the river at the side of the pub to the right are still named Pelican Stairs. The pub was also referred to as the Devil’s Tavern due to the reputation of the pub and the stairs as a haunt for smugglers and thieves. The name changed to the Prospect of Whitby in the late 18th century / early 19th century (I have found multiple years referenced as when the name changed) after a collier of the same name that berthed adjacent to the pub.

I suspect that the original pub may also have been a brewery, or there was an adjacent brewery. A number of newspaper articles reference the Pelican Brewery on Wapping Wall, for example the following from the Public Ledger and Daily Advertiser of the 18th May 1824:

“To Brewers, Publicans, Coopers, and Others, by Mr. Cockerell.

At the Pelican Brewery, Wapping Wall on Thursday, the 20th instant, at Eleven, Lots suitable to the Trade, Publicans, and Coopers, (in consequence of an agreed Dissolution of Partnership). About 550 Barrels of PORTER, STOUT and ALE; four capital Dray Horses, three Drays and Harness; about 850 casks, in Butts, Puncheons, Hog-heads, Barrels, and other, a quantity of Hops and other effects. may be viewed and tasted two days prior to the Sale.”

The area around the Prospect of Whitby must have been a scene of continuous coming and going of ships, cargo, sailors and passengers. There are also advertisements which indicate the type of trade carried on here. Again from the Public Ledger and Daily Advertiser of the 2nd December 1819 there is an advert for the new Brig Rolla which “carries 10 keels of coals at a light draft of water, sails fast, and shifts with all an end; adapted for the Mediterranean or Oporto Trade, or general purposes,; fitted for passengers, copper fastened and fitted with a busthead and quarter badges, also a high quarter deck.”

Researching the Prospect of Whitby provides a glimpse into the life of a docklands pub and landlord.

In June 1861, the landlord, a Mr Isaac who was also the Secretary of a Loan Society was in court to try to resolve a possible complex case of fraud where the recipient of a loan had disappeared, but leaving the person who requested the loan in Wapping to pay back the sum which he could not.

In 1858, the same Mr Isaac welcomed the officers of the East End district of the Ancient Order of Foresters to the Prospect of Whitby for the purpose of opening a new branch of the order. The account of the meeting states that a very large number of members from various courts were present, and there were several toasts given.

For many years in the 19th century, the Prospect of Whitby was part of a sculling regatta on the Thames which appears to have had a rather valuable prize money of a few hundred pounds. In October 1889 it was reported that “Weather of the most dispiriting description was associated with yesterday’s racing in connection with the regatta, which, as on Saturday, was decided on the ebb over the customary course between the Hermitage Wharf and the Prospect of Whitby, Wapping Wall.”

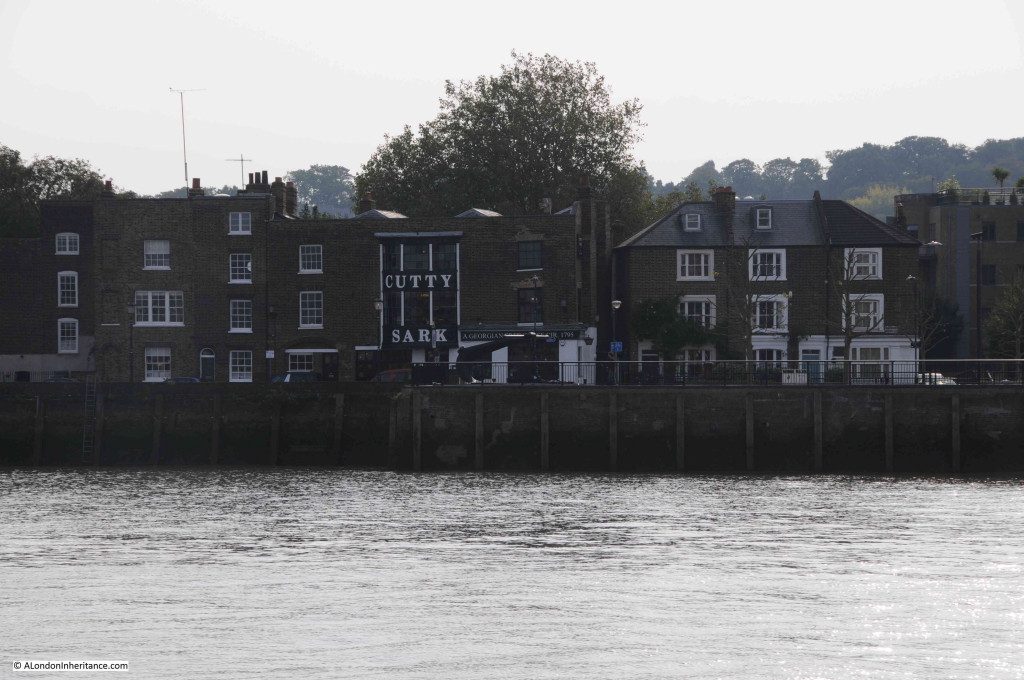

The Prospect of Whitby also claims Samuel Pepys, Charles Dickens, Whistler and Turner as customers. The Prospect of Whitby today:

Pelican Stairs running down the side of the Prospect of Whitby. Just imagine the stories of the number of people who must have passed down this alley on their way to and from ships on the river.

The Prospect of Whitby from the river with Pelican Stairs on the left.

The building immediately behind the Prospect of Whitby which can also be seen in my father’s and my photos of the bridge and pub, is the 1890 building of the London Hydraulic Power Company.

Once again, within the confines of a weekly post I have only just scratched the surface of the history of this area. Wapping is a fascinating area to walk, and rounding off with a drink in the Prospect of Whitby made for a perfect Autumn walk.