Before taking a walk along Fleet Street, a quick update on last week’s post.

Thanks for all the feedback via comments, e-mail and Twitter, which demonstrated that you cannot believe everything that you read in the papers, even back in 1915. Readers identified the following statues as earlier than that of Florence Nightingale, so my list of the first statues of women (not royalty) in London is now as follows:

- Sarah Siddons, unveiled at Paddington Green in 1897. Sarah was an actor, also known as the most “famous tragedienne of the 18th century”

- Boudicca, unveiled at the western end of Westminster Bridge in 1902. Some discussion about Boudicca as she could be classed as “royal” which the 1915 papers excluded, however I will keep her on the list

- Margaret MacDonald, unveiled at Lincoln’s Inn Fields in 1914. Margaret was a social reformer, feminist and member of organisations such as the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies

-

Florence Nightingale, unveiled at Waterloo Place in 1915

So that would put Florence Nightingale’s statue as the 4th public statue of a women unveiled in London (excluding royalty, or perhaps 3rd if Boudicca is classed as royalty).

Leave a comment if you know of any others.

The other point of discussion was the initials on the 1861 lamp post next to the Guards’ memorial. The combination of letters appeared to be SGFCG. Possibilities included the names of Guards Regiments, or a royal link with Saxe-Coburg Gotha (the Prince Consort as Colonel of the Guards was at the unveiling).

I e-mailed the Guards’ Museum and their feedback was that they had not seen the initials of the three Foot Guards Regiments combined in such a way elsewhere, however the initials do appear to fit the Regiments as they were known in 1861 – Grenadier, Coldstream and Scots Fusilier Guards.

Thanks again for all the feedback – there is always so much to learn about the city’s history.

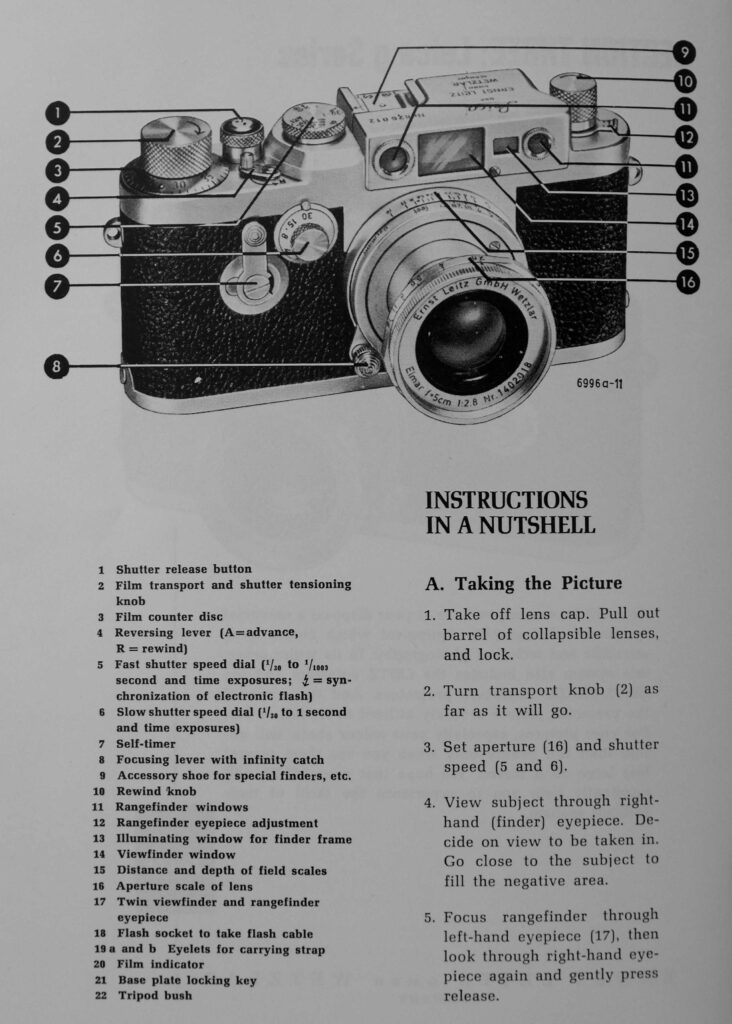

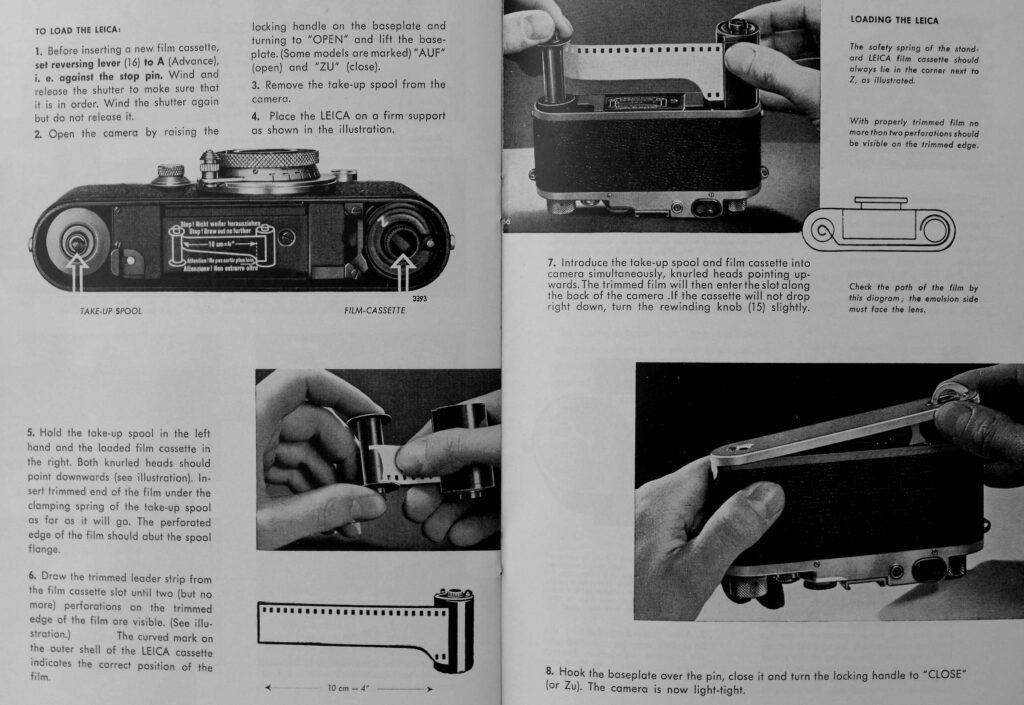

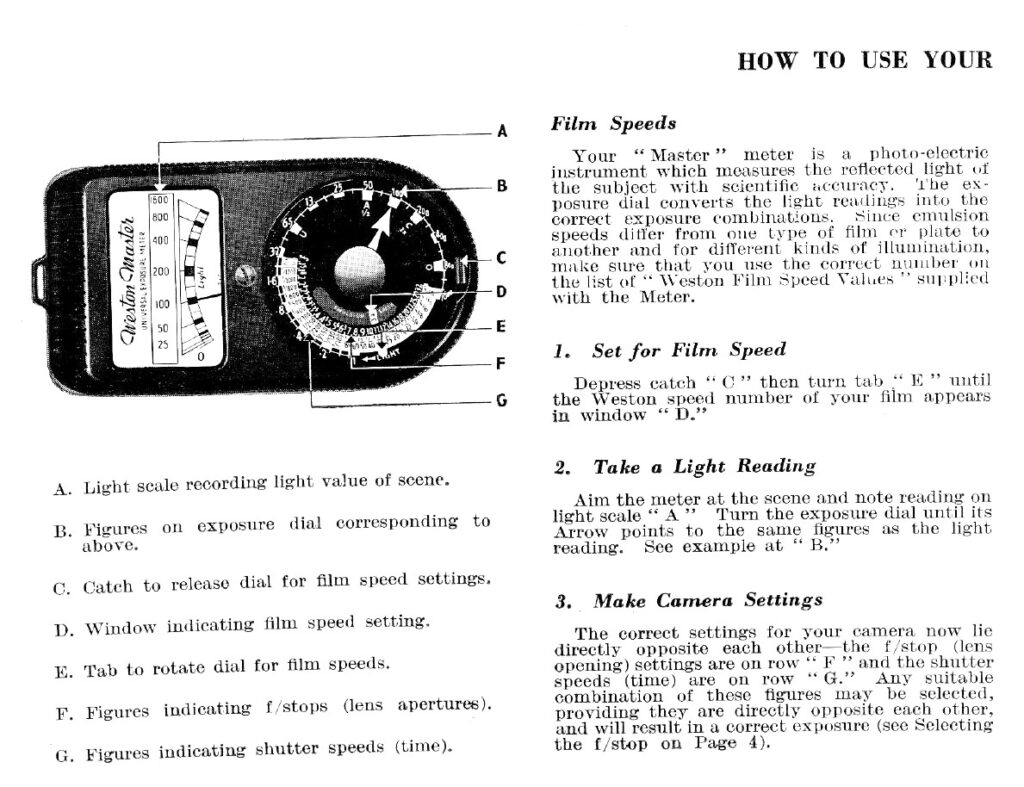

On to todays post. Last summer I took my father’s old Leica camera out for walk. The first time this 70 year old camera had been used in 40 years. To test the camera I had purchased a pack of Ilford black and white film, and as there were some spare, I decided to take my old film camera out, a Canon AE-1 which was my main camera for around 25 years, but last used in 2003.

The Canon AE-1 was a significant camera when it came out in 1976. I purchased mine in 1977 from a discount shop in Houndsditch in the City on Hire Purchase, spreading the cost over a year. It replaced a cheap Russian made Zenit camera which had a randomly sticking shutter as a feature.

The Canon AE-1 was a revolution at the time. The first camera to include a microprocessor, it included a light meter and once the desired speed had been set on the ring on the top of the camera, the aperture (how much light is let in through the lens) would be set automatically. It was also possible to set both speed and aperture manually.

Focus was still manual, via a focusing ring on the front of the included 50mm lens.

My Canon AE-1:

The camera was powered by a battery in the compartment to the left of the lens in the above photo. Having not used the camera for almost twenty years, my main concern was that on opening the compartment, I would be met by a corroded mess, however the battery, although flat, was in good condition, and after replacing with a new battery, the camera came back to life.

Inserting a new film was much easier than the Leica as the film did not need to be trimmed, simply pushing the end of the film into the take up spool and winding on until the rewind knob moved.

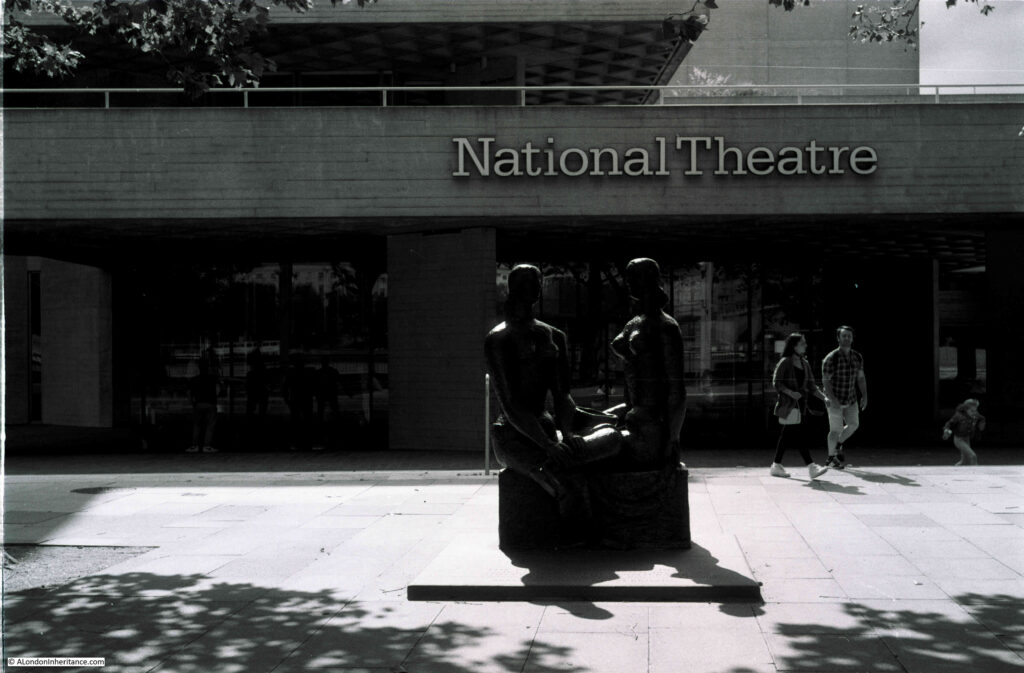

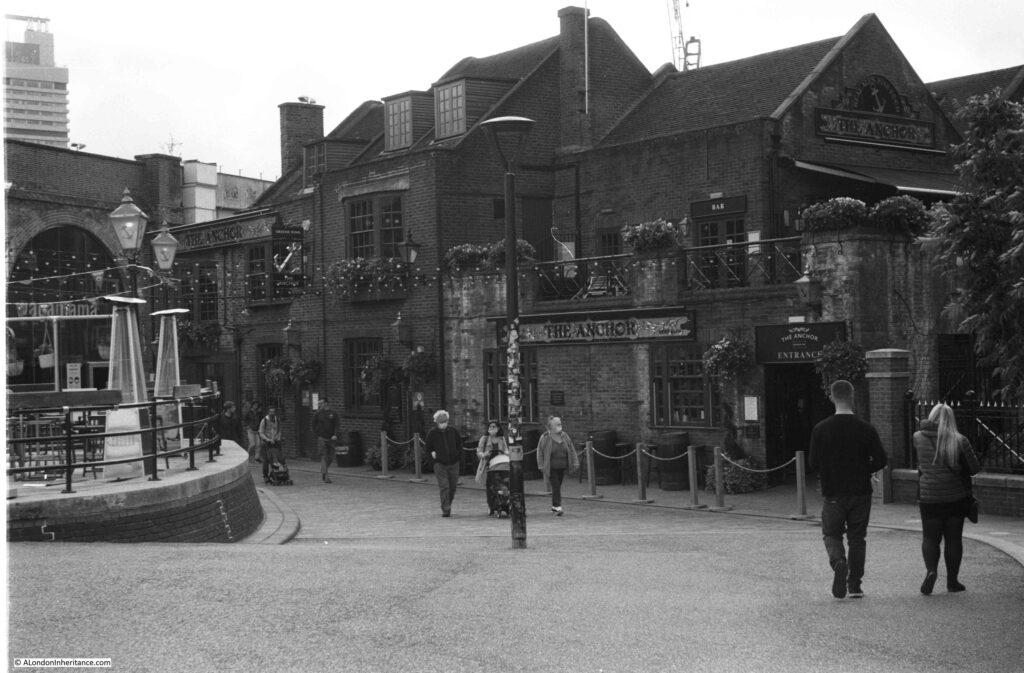

I took the camera for a walk along Fleet Street, hence the title of the post – Fleet Street in 32 Exposures. I was using a 36 exposure film, so lost some in initial testing to make sure the film was winding on correctly.

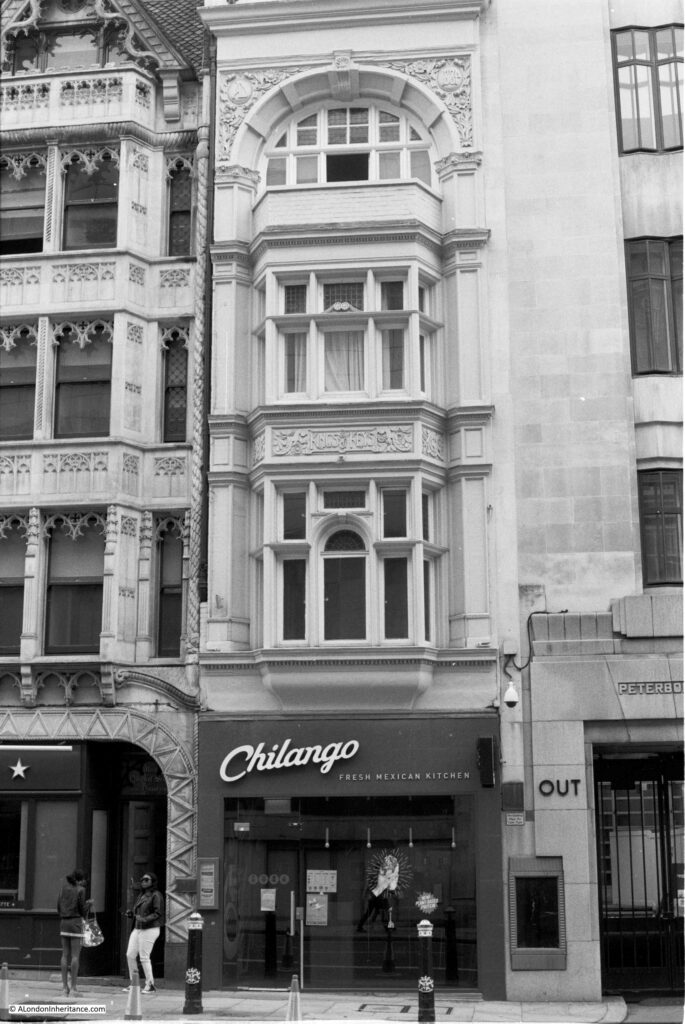

Fleet Street seemed a good choice, as the street is lined with fascinating buildings. Substantial buildings from when newspapers occupied much of the street, to tall, thin buildings which are evidence of the narrow plots of land that were once typical along this important street. Many of the buildings are also ornately decorated.

This will be a photographic look at the buildings rather than a historical walk. Fleet Street has so much history that it would take a few posts to cover.

So to start a black and white walk along Fleet Street. I started at the point where the Strand becomes Fleet Street and the Temple Bar memorial:

The Temple Bar memorial dates from 1880 and was designed by Sir Horace Jones. It marks the location of Wren’s Temple Bar which marked the ceremonial entrance to the City of London. The original Temple Bar now stands at the entrance to Paternoster Square from St Paul’s Churchyard.

Statues of Queen Victoria and the Prince of Wales are on either side of the monument, which is also heavily decorated and shows the Victorian fascination with the arts and sciences, with representations of these lining either side of the alcoves with the statues.

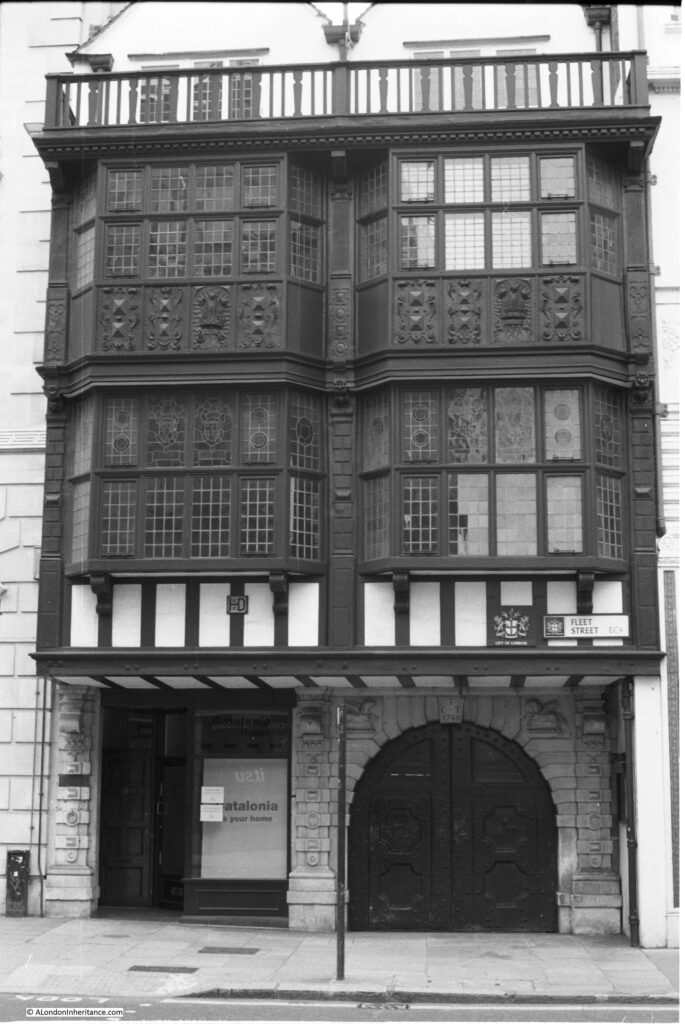

The Grade I listed Middle Temple Gatehouse which leads from Fleet Street into Middle Temple Lane. The building originally dates from 1684:

The Grade II* listed Inner Temple Gatehouse between Fleet Street and the Inner Temple location of Temple Church:

Cliffords Inn Passage and the entrance gate to Cliffords Inn:

The church of St Dunstan in the West:

The head office building of the private bank of C. Hoare & Co. Founded by Richard Hoare in 1672, the bank has been based here in Fleet Street since 1690:

Offices of publishing company DC Thomson, who still publish the Sunday Post and People’s Friend as well as the Beano. This is their London office, with their head offices being in Dundee (hence the Dundee Courier):

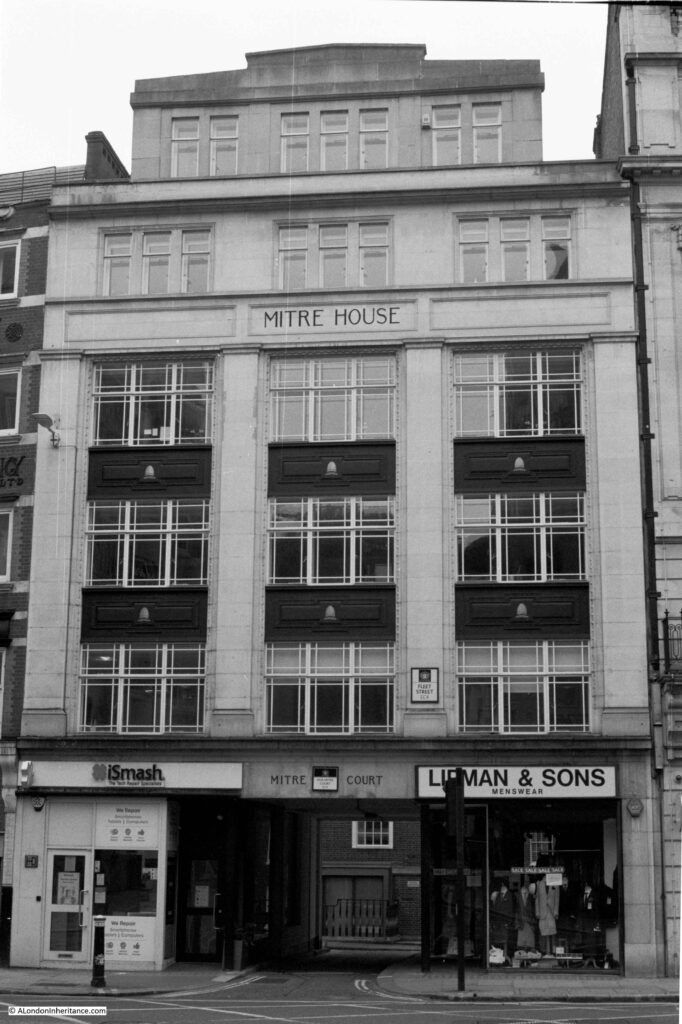

Mitre House, with the entrance to Mitre Court:

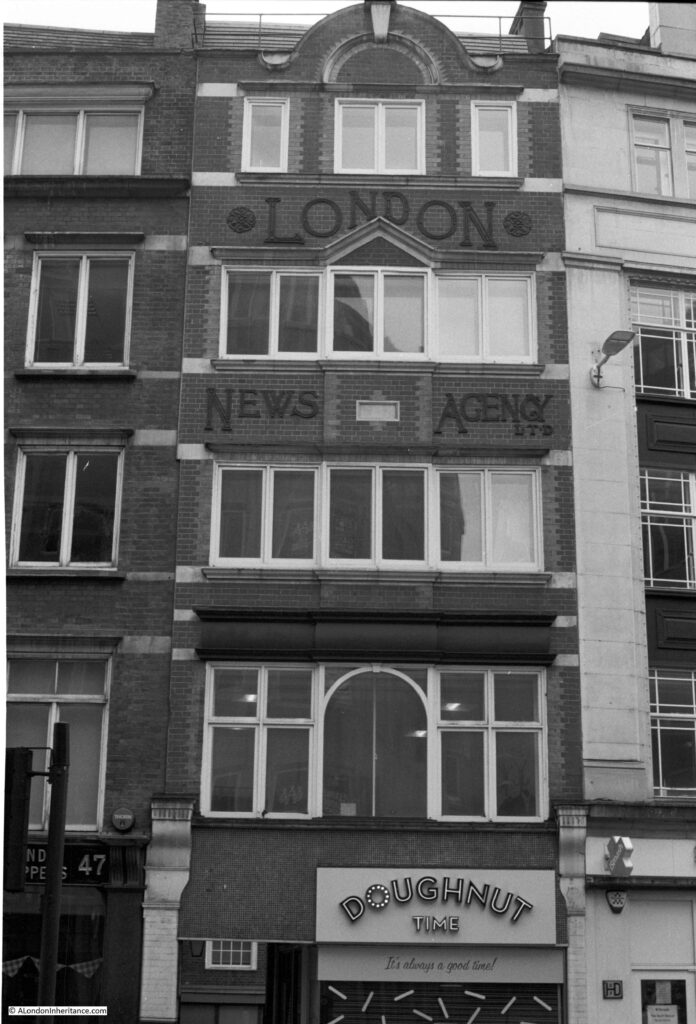

The original home of the London News Agency, also known as the Fleet Street News Agency. The business was here in Fleet Street from 1893 until 1972 when the business moved to Clerkenwell, where it was based until the agency closed in 1996.

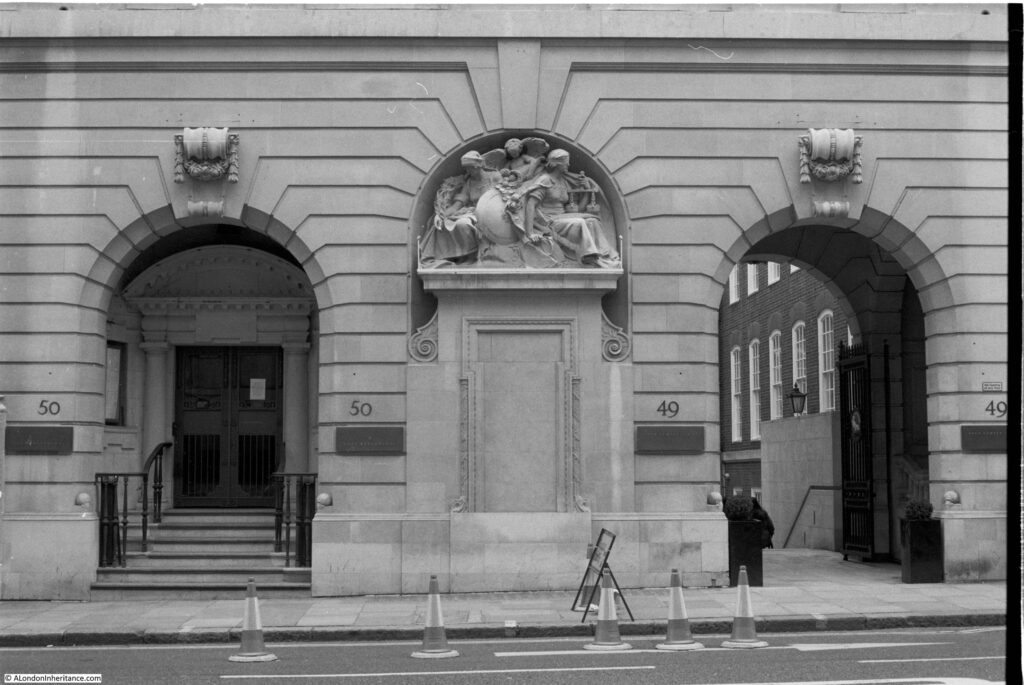

The entrance to 49 and 50 Fleet Street, a Grade II listed building that dates from 1911. Originally Barristers’ Chambers, in 2018 the building was converted into an extension to the Apex Temple Court Hotel.

The following photo is of 53 Fleet Street and is a good example of where black and white is the wrong film to capture the features of a building. The upper floors are decorated with dark red bricks with green bricks forming diamond patterns, which can just be seen in the photo. It looks much better in colour.

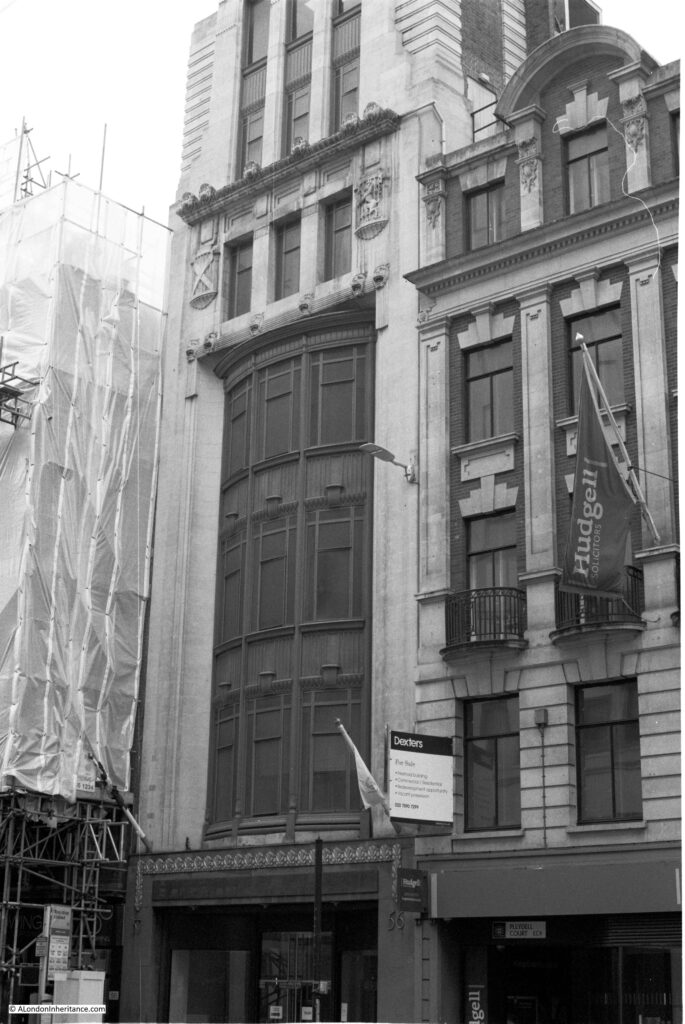

The following building is the Grade II listed former office of the Glasgow Herald built in 1927. The building is relatively thin and tall and the challenges with photographing the building using a fixed 50mm lens are apparent as I could not get in the top of the building without the front being at too oblique an angle.

The 1920’s Bouverie House, with entrance to St Dunstans Court at lower left:

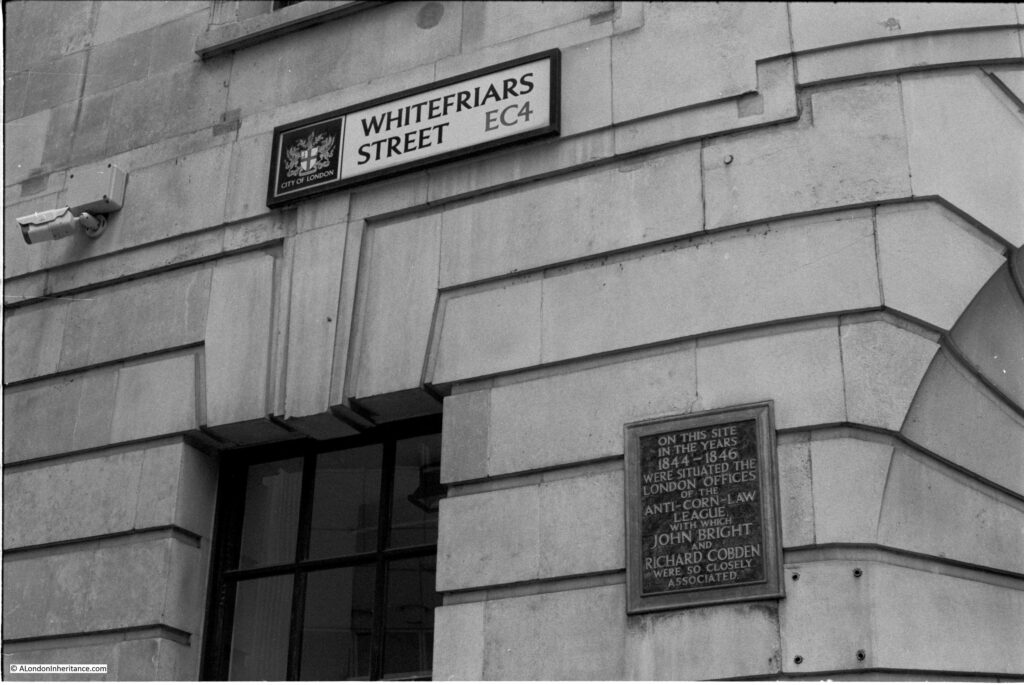

Almost opposite Bouverie House, Whitefriars Street leads off from Fleet Street. A plaque on the wall records that this was the location of the office of the Anti-Corn-Law League between 1844 and 1846.

A wider view of the building on the corner of Whitefriars Street and Fleet Street. The above plaque can be seen on the wall to the left of the corner entrance. The pub just to the right of the corner building is the Tipperary at 66 Fleet Street.

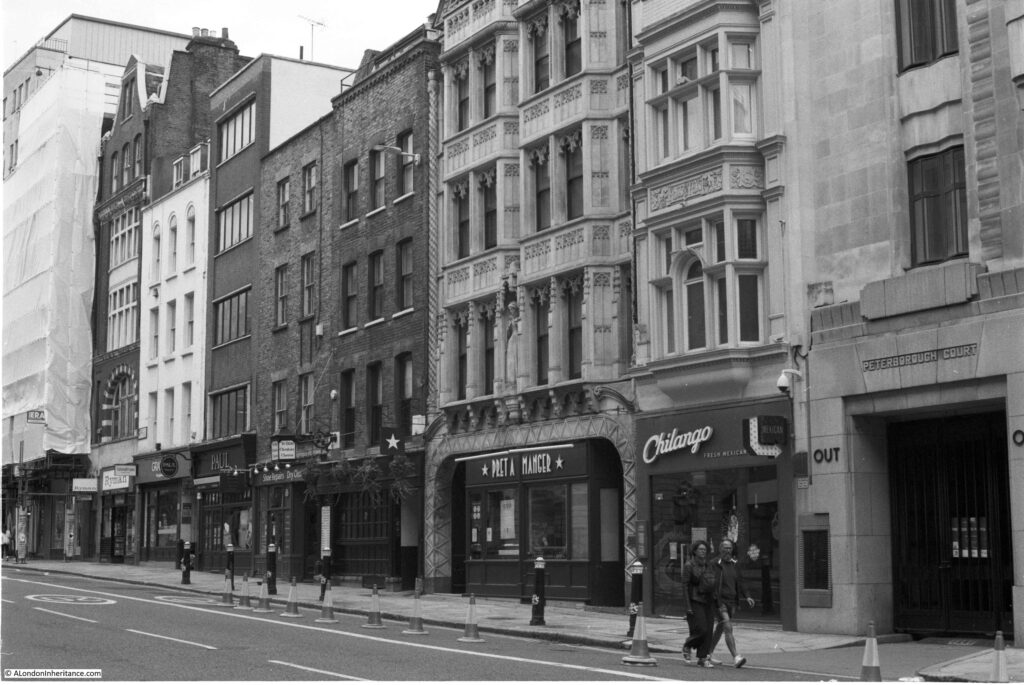

The following photo shows a view along the northern side of Fleet Street and highlights the mix of different building ages, materials and architectural styles that make this street so interesting. One of the oldest building on the street is in the centre of the view. The Cheshire Cheese pub dates from 1538 with the current building dating to 1667.

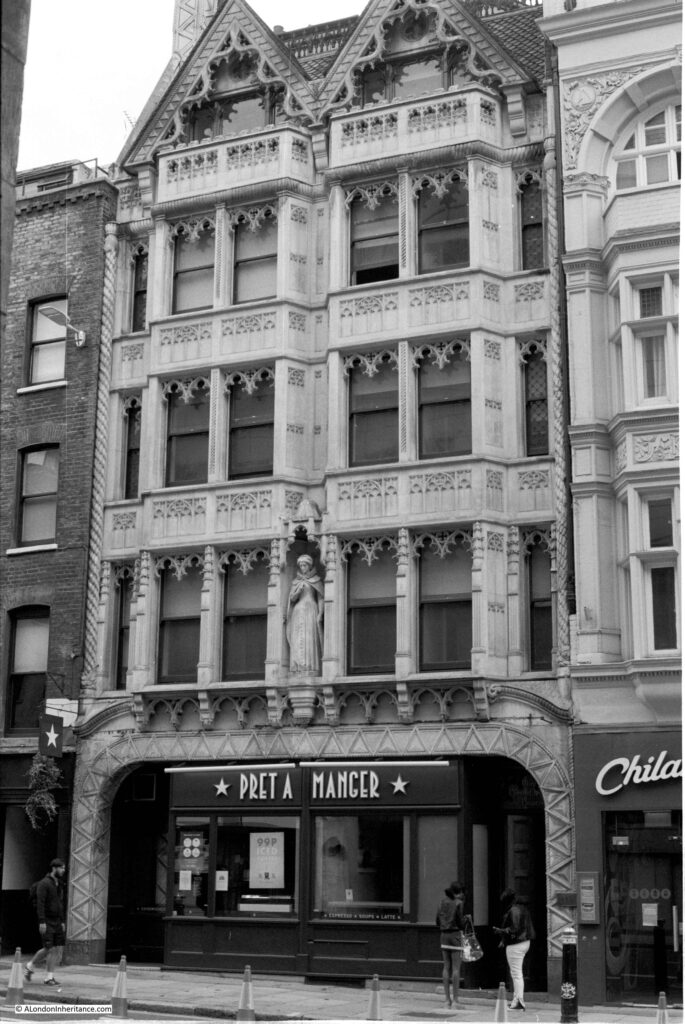

Next to the Cheshire Cheese is this rather ornate building which is currently home to a Pret on the ground floor. This is the Grade II listed, 143 and 144 Fleet Street. The statue in the centre of the first floor is of Mary, Queen of Scots.

The building in the above photo was constructed in 1905 for Sir John Tollemache Sinclair, a Scottish MP, and designed by the architect R.M. Roe. Whilst researching for the reason why the statue is on the building (Sinclair was a fan of Mary Queen of Scots), I found the following newspaper report from The Sphere on the 17th August 1946 which provides a description of the use of the building:

“Although at first glance, this life-size statue of Mary, Queen of Scots appears to be in an ecclesiastical setting, it is, in fact, situated above a chemist’s shop and a restaurant in one of the older and grimier buildings of Fleet Street. No. 143-144 Fleet Street, known as Mary, Queen of Scots House, contains a typical selection of Fleet Street tenants – newspaper offices, advertising agents and artists agents”

Next to the above building is a lost pub, the building in the following photo was once the Kings and Keys pub.

The name of the pub can still be seen carved in the decoration between the first and second floors.

The Kings and Keys closed in 2007, and in the days when Fleet Street newspapers had their local pub, this was the pub for the Daily Telegraph. Although the building dates from the late 19th century, a pub with the name Kings and Keys had long been on the site. A newspaper report from 1804 highlights the dangers for those travelling through London and stopping at a pub:

“Last week a young midshipman, from Dover, going to Oxford on a visit to his relations, stopped at the King and Keys, in Fleet-street, for refreshment, when a fellow-traveler, whom he had supported on the road, attempted to rob him of his box, containing his money and clothes, which was prevented by the waiter; the ungrateful villain unfortunately made his escape”.

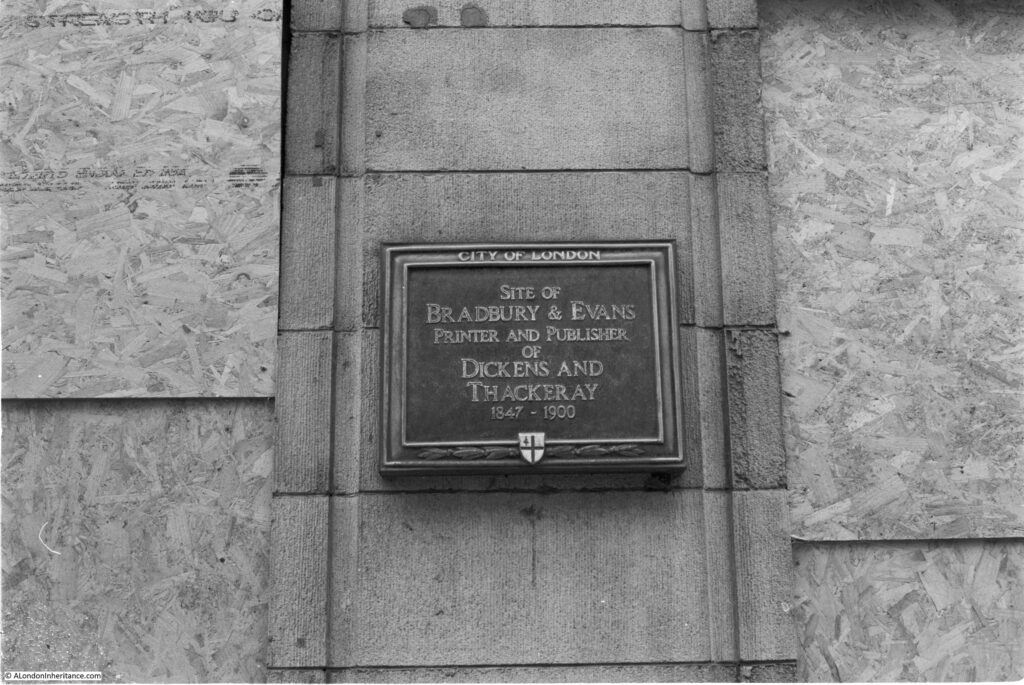

Across the road is a closed and boarded Sainsbury’s Local. One of the casualties of the lack of people travelling to work in Fleet Street during the lock-downs.

On the front of the above building is a plaque recording that it was the site of Bradbury and Evans, Printer and Publisher of Dickens and Thackeray between 1847 and 1900.

And to the left of the building is a memorial to T.P. O’Connor, Journalist and Parliamentarian 1848 to 1929 – “His pen could lay bare the bones of a book or the soul of a statesman in a few vivid lines”.

Next to the old Kings and Keys building is the old offices of the Daily Telegraph newspaper. Built for the newspaper in 1928 and now Grade II listed.

The building is a good example of the power and authority that the newspapers wanted to project when they were still the main source of news, before radio and television had become a mass market source of news.

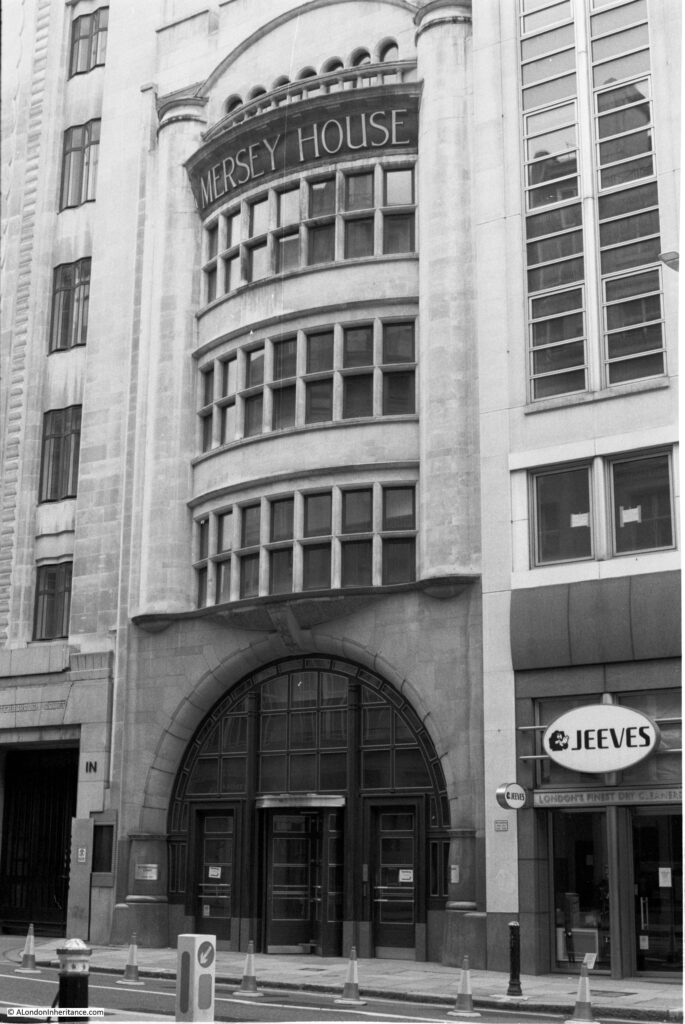

Next to the Telegraph building is Mersey House, built between 1904 and 1906:

Mersey House is yet another Grade II listed building, and was the London home of the Liverpool Daily Post (which is probably the source of the Mersey name after the River Mersey). The newspaper cannot have been using all the space in the building as in 1941 they were advertising:

“Do you want a London Office with a Central and Appropriate Address? Accommodation can be had in Mersey House, Fleet Street, E.C. 4 – Apply the Daily Post and Echo, Victoria Street, Liverpool”.

There are substantial stone clad buildings on many of the corners of Fleet Street. This is 130 Fleet Street on the corner with Shoe Lane:

And a typical bank building on the corner with Salisbury Court. The plaque to the right of the door records that “The Fleet Conduit Stood In This Street Providing Free Water 1388 to 1666”.

The majority of buildings that line Fleet Street are of stone, however there is one spectacular building of a very different design and using very different materials. The following photo shows the lower floors of the Grade II* listed Daily Express building dating from 1932.

The above photo shows the limitations of using a fixed lens. impossible to get the whole building in a single photo. These are the upper floors:

The art deco building was designed by architects H. O. Ellis & Clarke with engineer Sir Owen Williams. The materials used for the building could not be more different than the rest of Fleet Street.

Vitrolite (pigmented, structural glass) along with glass and chromium strips formed the façade of the building, to give the building a very modern, clean and functional appearance at the start of the 1930s.

Four years after completion, the building was used as an example in an article on “Architecture – the way we are going” in Reynolds’s Newspaper to demonstrate the battle of architectural ideas, and the type of design and materials that will be the future of office and industrial buildings

The building can really be appreciated when seen as a complete building, and the following postcard issued as construction was finishing, shows the building in all its glory:

On the opposite side of the street is the old building of the Reuters news agency, one of the last of the news agencies to leave Fleet Street in 2005. The following photo shows the main entrance to the building and according to Pevsner is recognisable as the work of the architect Sir Edward Lutyens by “the wide, deep entrance niche on the narrower Fleet Street front”. Above the door, in the round window is the bronze figure of Fame.

View looking down Fleet Street, with the dome of St Paul’s Cathedral in the distance:

The following photo is looking back up Fleet Street. in the centre of the road is one of the old police sentry boxes introduced during the early 1990s in response to the IRA bombing campaign in the City of London.

I have now come to Ludgate Circus, where Fleet Street meets Farringdon Street, and where the old river that gave the street its name once ran.

The clock on Ludgate House:

That is Fleet Street in 32 exposures, and it proved that my 44 year old camera is still working.

The Canon AE-1 was a joy to use. Taking photographs with a film camera does feel very satisfying. After each photo, the act of pulling the lever to wind the film feels like you have done something a bit more substantial than just the shutter click of a digital camera.

There is a story that Apple used the sound of the shutter on the Canon AE-1 as the sound when taking a photo on an iPhone – it does sound very similar, but I am not convinced.

Black and White photography is good for certain types of photo. It does bring out the texture in building materials, but I still have much to learn to use this type of film for the right type of photo (when using the Canon I mainly used colour film).

The fixed 50mm lens was also a problem with trying to photograph larger buildings in a confined space. In my early years of using the camera I could not afford any additional Canon lens, but did buy compatible Vivitar 28mm and 135mm lens which I need to find.

Fleet Street has such a rich collection of architectural styles, and the legacy that the newspapers have left on the street is still very clear. It is a fascinating street to walk.