At the end of today’s post, there is another of my monthly features on research resources, as well as a London book, but before that, a search for the location of a lost London priory.

If you hear the word Blackfriars, you probably think of either the station, the bridge, or perhaps of the pub at the southern end of Queen Victoria Street:

You may also think of the religious institution after which the station, bridge and pub are named, a house of Dominican Friars, who became known as Black Friars after the black cape they would wrap around their body, an image which the figure on the pub seeks to illustrate.

Within the area known as Blackfriars, and at the end of Carter Lane, where the street meets Ludgate Broadway and Black Friars Lane, there is a plaque on the wall, seen to the right of the red truck in the following photo:

The plaque records that it is the site of the Priory of the Blackfriars, founded 1278:

However, the Priory was a large complex, so how does this plaque relate to the Priory, and what area did it cover in the streets between Carter Lane and Queen Victoria Street? That is the purpose of today’s post, but first a bit of background to the Black Friars.

The Dominican Order was founded by Saint Dominic, who was a Castilian Priest by the name of Dominic de Guzmán, in the early 13th century.

The order was founded to build a community of priests who would go out into the world to preach, and the Dominican’s are also known as the Order of Preachers. The early 13th century was a time when there were challenges to the established church across Europe, with the Albigensian heresy of the Cathars in the Languedoc area of southern France and a growing scepticism of the compatibility of faith and reason.

The Dominican approach to combating these challenges was to go out and preach, and to bring a learned, intellectual and rigorous approach to both theology and preaching.

The new order quickly expanded across Europe, and arrived in London in 1221, with Gilbert de Fresnay being the first friar.

Gilbert de Fresnay was charged with finding a site in London to establish their second English Priory (the first had already be established in Oxford). He had the support of Hubert de Burgh, the Earl of Kent, who purchased a plot of land in Holborn, on the western banks of the River Fleet, and by the Fleet Bridge (today the area of land between the church of St. Andrew and Shoe Lane, down to Farringdon Street).

Hubert de Burgh gave this land to the Dominican’s for their new Priory.

Although it was outside of the City walls, it was an important location as it was adjacent to the street that led from the west, over the Fleet, and into the City of London, and as I mentioned in this post on Churches at City Boundaries, it was a good place to cater to the spiritual needs of those travelling to and from the City, and to seek donations for the Order.

The Holborn Priory would serve the Dominican’s for around 50 years, but by the 1270s, the order wanted to move into the City of London and had been gradually acquiring land in the area we today call Blackfriars.

The area they were targeting for their new Priory was mainly comprised of several large properties, so they did not have the challenge of trying to buy up a dense area of streets and housing. The land to the south west of the City had large buildings such as Baynard’s Castle and Mountfitchet’s Tower.

The main problem was that the old City wall crossed through the area that the Dominican’s were after, and in a remarkable decision which involved the Mayor of London, the King and representatives from the Dominicans, agreement was reached on demolishing 225 yards of the existing City wall, and rebuilding it to the western boundary of the new priory, along the eastern bank of the River Fleet.

Construction of the new priory got underway, the friars moved from Holborn into the City, however it would be some decades into the early 14th century before their Priory was complete (and like all such buildings, it would be under almost continuous modification).

The Dominican priory would continue to be based in this area of the southwestern City until the middle 16th century, when the buildings and lands was surrendered to Henry VIII during the Dissolution, and in 1549 / 50 the priory site was sold to Thomas Cawardine.

The friars in their black capes over their white robes must have been a common sight in the area, and almost 500 years after the friary was closed, the area still goes by the name of Blackfriars.

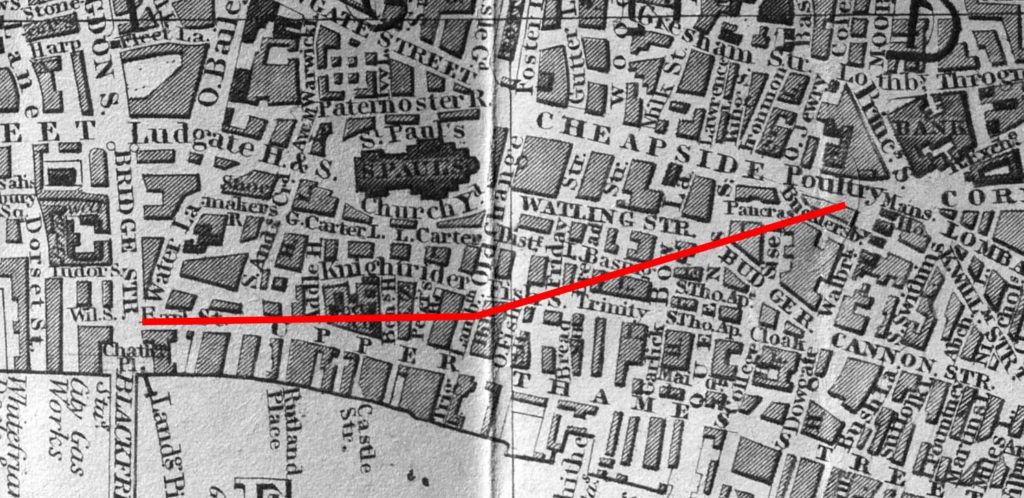

So where exactly was the Priory, and how much land did it cover?

A Dictionary of London (Harben, 1918), included a map of the Priory, overlaid on the early 20th century street plan. There are some small differences between this plan and some modern interpretations, based on 20th century archaeology, and I will point these out, however the Priory evolved over the almost 300 years that it occupied the site, so the purpose of many of the buildings would have changed, but the layout and key buildings in a Priory would have stayed the same, just improved and repaired over the years that the site was in use:

The blue plaque marking the site of the Priory of the Blackfriars, shown earlier in the post, is at the north western edge of the priory buildings. If you find Carter Lane along the top of the plan, with the Lady Chapel, where Carter Lane meets Water Lane (the street that today is Black Friars Lane), the plaque is on what would have been the northern wall of the Lady Chapel, above the L of Lady.

I am starting a walk around the site of the Priory at the southern end of Black Friars Lane, where it meets Queen Victoria Street. In the above plan, this is the space to lower left which leads up to what was Water Lane.

On the left of the following photo would have been gardens, workshops and a smithy, leading down to the relocated City wall and the River Fleet. On the right would have been the Kitchen Yard and the Parliament Hall or Chamber:

Note that in the early 20th century street plan shown in red in the above plan, Printing House Square is shown to the right, and behind the Parliament Hall.

The buildings around Printing House Square were where the offices and printing machinery of the Times newspaper were based after John Walter brought the King’s Printing House in Blackfriars in 1784.

Further up, we reach the junction with Playhouse Yard. Black Friars Lane continues up to Carter Lane. The buildings on the left appear rather strange as their depth has been reduced to provide space for the railway, which now allows the Thameslink trains to run into Blackfriars Station, the tracks are behind the wall on the left:

In the above photo, the turning on the right is into Play House Yard. The name comes from the Blackfriars Theatre that was on part of the site between 1596 and 1655. The theatre seems to have been mainly used during the winter months. The Globe and Rose theatres on the low lying south bank of the river would often be surrounded by muddy water following heavy rains and when the Thames breached the limited river bank defences then in place, so Blackfriars, on a rising slope above the Thames was a good alternative.

This is the view looking into Play House Yard, and here we are coming from the Kitchen Yard, crossing the Kitchen, and part of the Refectory (or Frater as shown in the above plan), with the southern part of the main cloister in the distance:

Offices are in the building on the left, and just a bit further to the left, behind the offices is Apothecaries’ Hall.

The Apothecaries’ moved into the old Guest House of the Priory, which became their Hall in 1632. The building was lost during the Great Fire of 1666, and the Apothecaries’ rebuilt their hall on the same site in 1670, with some rebuilding in 1786, from when the brick parts of the overall complex, facing the street in the above and below photos date from.

The Hall is Grade I listed, and according to the listing the Hall includes “slight medieval remains of Blackfriars’ Priory”. The Apothecaries’ Hall from Black Friars Lane:

The Porter’s Lodge of the Priory was located where the Apothecaries’ Hall meets Black Friars Lane, and from here a gallery provided a walking route down to the new location of the City Wall alongside the Fleet, where there was a small crossing over the Fleet.

In Play House Yard, looking back towards the entrance from Black Friars Lane, and the buildings around the Apothecaries’ Hall are directly in front. This is where the Guest Hall and Guest House were located. To the right was the southern side of the main Cloister:

To the right of the above photo is an alley by the name of Church Entry and which leads up to Carter Lane. It is here that we find the core of the Priory. In the following photo looking north along Church Entry, the eastern side of the main Cloister would have been on the left. To the right was a School House, then a Chapter House, and further along the alley, just past where the white wall juts in from the left, would have been the magnificent tower of the Priory’s church:

To the left of Church Entry was the Nave and the Choir was to the right, with the tower between. The name Church Entry for the alley is down to the alley being the entry point into the church, running north-south underneath the tower.

Along Church Entry is the entrance to a raised garden:

This open space was once part of the Preaching Nave of the Priory Church. After the Nave was demolished, the space was used as a churchyard for the parish of St. Ann, Blackfriars. Closed for burials in 1849, it is now a garden maintained by the City.

In the years when the Priory was in use, the Nave would have extended to the left of the following photo, and through the buildings that now occupy the space on the left. This would have been one of the most important parts of the Priory. In the plan of the Priory, it is labelled as the Preaching Nave, as this is where the friars would have fulfilled one of the Order’s main roles of preaching.

One of the major events early in the life of the Priory was the Priory’s role in the funeral of Eleanor of Castile. After the funeral of Eleanor at Westminster Abbey, there was one last act for her husband Edward I to attend to, and that was the burial of Eleanor’s heart at the Dominican Priory at Blackfriars on Tuesday the 19th of December, 1290.

The priory at Blackfriars was well known to Edward and Eleanor as the heart of their son Alfonso who had died in 1284 at the age of 10 had already been buried at Blackfriars, so Eleanor probably had been planning for her heart to be buried with that of her son. (for more on Eleanor of Castile, see my series of posts on the line of Eleanor Crosses and the journey from the place of her death, back to London, starting in this post),

It was also Edward I who had specified that the redirected City wall, along the River Fleet was to be built at the expense of the City. A decision which must have pleased the Friars.

There are very few records of life within the priory, and most recorded events come from the time of Henry VIII. In 1522, the visiting Emperor Charles V was put up by Henry VIII at the priory, and Henry VIII had a covered gallery constructed from the western edge of the priory across from the Porter’s Lodge down to Bridewell Bridge, which crossed the Fleet and gave access to Henry’s new palace at Bridewell, enabling Charles V to reach the palace from his lodging in the priory without getting wet if it rained.

The Gallery can just be seen on the left edge of the plan of the priory earlier in the post.

During Henry VIII’s divorce from Catherine of Aragon, Catherine was put on trial before the papal legate at the priory.

Where Church Entry meets Carter Lane:

Walking back to Play House Yard, I then turned east into Ireland Yard, as here we can see a small bit of stone wall that was possibly part of the medieval Priory.

Ireland Yard takes its name from the Ireland family. Early in the 17th century a William Ireland owned property here, and for some reason, the family gave their name to the street, which runs between Play House Yard and St. Andrew’s Hill.

A short distance along Ireland Yard, on the northern side are these brick walls with a gate and steps leading up to a raised open space:

Walk up the steps, look to the right and you will see the remains of a wall:

This fragment of a rubble wall is Grade II listed, and in the listing record it is stated that it is “Probably part of former Dominican Convent (Blackfriars)”.

The use of “probably” illustrates the problem of being really sure when describing the origins of small bits of a structure. If it is from the Priory, then it would possibly have formed the southern wall of the Provincial’s Hall.

The Provincial’s Hall had an upper floor so a strong wall would have been needed. The plan of the Priory states that over the hall was a Dorter (the sleeping area for the friars).

The open space at the top of the steps, looking back towards Ireland Yard is shown in the following photo. The Provincial’s Hall with the friars sleeping quarters ran across the southern part of this space, by the steps. To the right was the Chapter House, and it seems that the parish church of St. Ann may have used the Chapter House, with the churchyard occupying part of this space, as well as the space in Church Entry where the Nave of the Priory Church was located:

Continuing along Ireland Yard, and the next street running up to Carter Lane is Friar Street:

Friar Street marks the easterly limit of the buildings that made up the Priory. The Priory estate continued to the east with the Prior’s Garden which ran all the way to what is now St. Andrew’s Hill.

In the above photo, the eastern end of the Choir was to the left of the far end of the street, and where Friar Street meets Ireland Yard was the eastern end of the Provincial’s Hall. The Prior’s Gardens were to the right of the above photo.

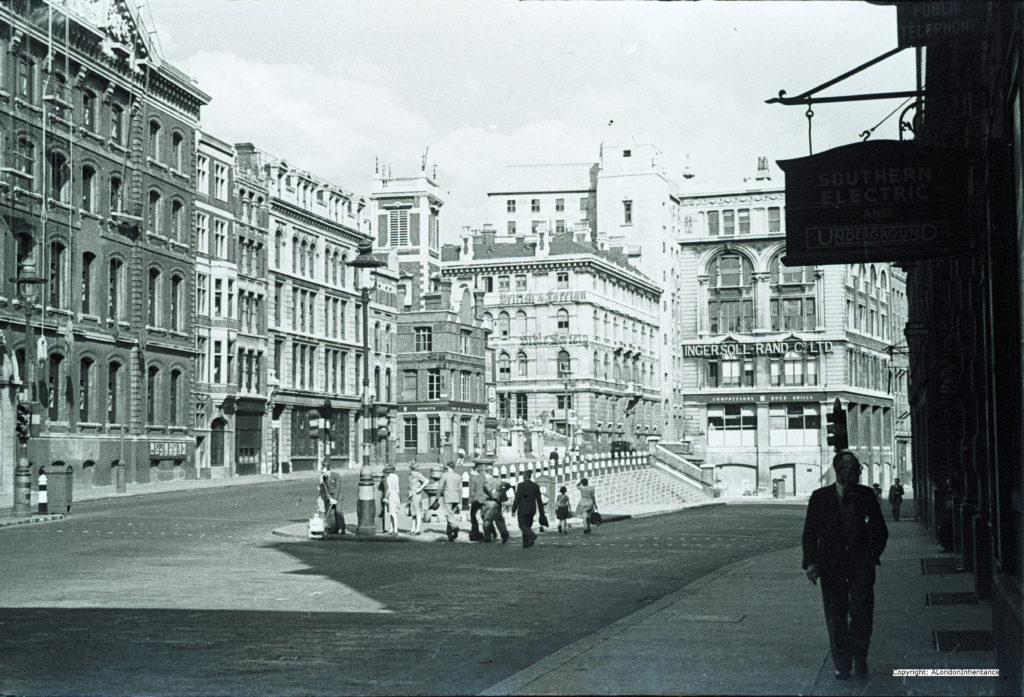

Continuing along Ireland Yard, and we come to St. Andrew’s Hill, a street that runs up from Queen Victoria Street to Carter Lane.

St. Andrew’s Hill was originally Puddle Dock Hill as the street ran down to Puddle Dock on the Thames, which was used by the Friars as their access to the river.

St. Andrew’s Hill / Puddle Dock Hill formed the eastern boundary of the Friary, and it was at the junction with Ireland Yard that the east gatehouse was located.

On the left of the entrance to Ireland Yard is the Cockpit pub. The current pub building is mainly from 1842, however a pub is alleged to have been here from the 16th century and the name is a reference to cock-fighting and the associated gambling that once took place here. It would have been a logical place for a pub, right next to the gatehouse to the old Friary estate.

There is a reference to the gatehouse on the plaque on the building to the right in the above photo. The plaque records that William Shakespeare purchased lodgings in the Blackfriars Gatehouse on the 19th of March, 1613:

Walking up to Carter Lane, and looking west from the north east corner of the Friary estate:

It is interesting how street patterns retain a memory from what was there in previous centuries.

In the above photo, the boundary wall of the Priory estate cut across the wider part of the road, then turned a short distance up the road to the right, before heading north west, where it met the City wall at the point where it had been redirected to the west to free up space for the Friary.

So in the above photo, where Carter Lane narrows is the point where the street ran within the Priory, with Priory buildings to the left, and the principal graveyard of the Priory to the right. The narrowing of Carter Lane my reflect that the narrow part ran within the Priory grounds..

At the western end of Carter Lane, I meet the junction with Ludgate Broadway and Black Friars Lane, and the following photo is looking back along Carter Lane. The impressive nave of the church was on the right, the principal graveyard was on the left. Behind me, gardens ran down to the rerouted City wall which then ran along the banks of the River Fleet, now New Bridge Street:

Whilst a single part of what may have been a rubble stone wall of the Priory remains above ground, there are still arcaeological remains below ground, however the majority of the Priory remains have been lost.

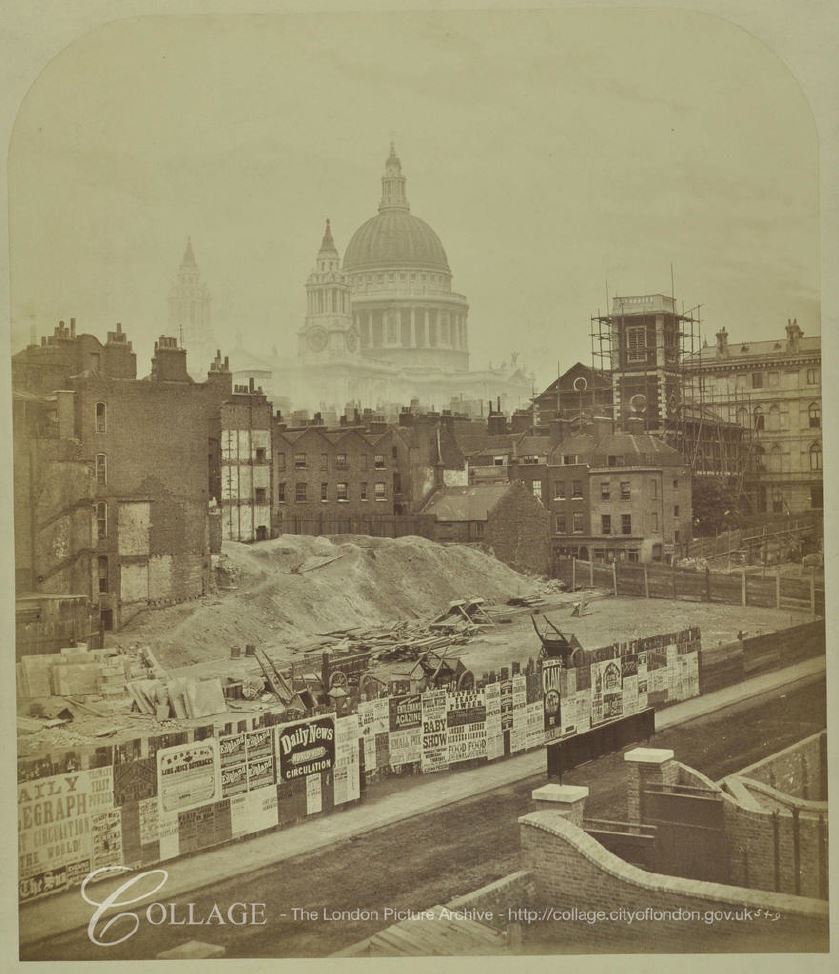

During the mid-19th century, John Wykeham Archer recorded a number of the surviving parts of the Priory in a series of prints. The following print dates from 1853 and shows the remains of a wall and base of a pillar underneath the Times printing office (all the following three prints are: © The Trustees of the British Museum. Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence.):

The following from 1855 shows the remains of an arch:

And the following print, also from 1855, shows the base of a tower. In the print above and that below, there are men looking as if they are breaking up the structure and carrying stones away in baskets. This must have been the fate of much of the old Priory with the stone being reused in other construction projects:

In a few decades time, it will be 500 years since the Dominican Order surrendered their Priory to Henry VIII, the site sold off and the area began the transformation to the place we see today.

The Priory occupied a large area, it required a significant rerouting of the City wall, and appears to have been an impressive place, with the central nave, choir and tower dominating the Priory.

It lasted for just under 300 years, but the name that came from the sight of the Friars in their black capes still resonates through the area today.

Resources – Mapping at the National Library of Scotland

And now for the second of my monthly additions to a post detailing some of the resources I use for research, and for this month there is a website that can easily lead to an evening of distraction as you explore the street layout of places from over 100 years ago.

The National Library of Scotland has an extensive range of maps which have been digitised and aligned with maps of today. These maps cover not only London, but much of the country, so for example, if you want to see the countryside and villages lost under Harlow new town, as they were at the end of the 19th century, or how much Lincoln has expanded from a country town to the city it is today, it is all there.

The website is at: https://maps.nls.uk/ where you will find the following page:

Click on Geo-referenced maps in the top row of options, and you will be taken to a map with an Ordnance Survey map overlaying a modern map.

From here you can zoom in and out and move the map with a mouse, and at bottom left there is a “Change transparency of overlay” slider where you can reveal the modern base map to help with locating a place before going back to the older map.

Above the slider, you can select a map. The OS Six Inch 1888-1915 is a good place to start, but clicking the down arrow to the right of the select a map box will bring up a list of other available maps. There are plenty to explore.

From the main page shown above you can also view a “Side by side viewer” which places an old and a modern map next to each other, and zooming in and out, or moving one of the maps synchronises with the other map.

There is much to explore at the site, and it is worthwhile spending some time exploring all the different features and options to get to know how the site work, or just zoom in on your current street or home town to see what was there at the end of the 19th century.

The National Library of Scotland have done a remarkable job with putting these maps on line, aligning with maps of today, and making the site so easy to use – a wonderful resource, not just for London, but the whole country.

What I Am Reading – Maritime Metropolis by Sarah Palmer

I also thought I would include in these resources additions to posts, a monthly book, and for this month it is a book that I have just purchased and am currently reading, Maritime Metropolis London and its Port, 1780-1914 by Sarah Palmer:

I have been hesitating to buy this book for some time as the published price of the book is £90, but finally purchased a copy as the subject to so close to my interest in the relationship between London and river and docks that made up the Port.

It is published by Cambridge University Press so could come under the category of an academic title, hence the price.

Many histories of London look at either the city or the port, almost in isolation, however the approach taken by Sarah Palmer in Maritime Metropolis is that the history of both are intertwined. London is a Port City and almost every aspect of the city’s development has been influenced by the port, and the port was able to develop because of London.

This is a view that I have long taken, and today, with the loss of the docks, London has in many ways lost its connection with the river, and the route to the world that the river provided.

It is also why London has in some ways lost its identity. It is no longer a port city, it is no longer home to the largest dock complex in the world, and the enormous volumes of trade that once passed through the city. Indeed up until the later part of the 20th century, ships taking goods to and from London has been a key part of the city’s function, and in the lives of the city’s residents, for almost its entire history.

If you want to understand the deep connection between London and its Port, then Maritime Metropolis is a comprehensive and very readable account.