Queen Victoria Street is probably one of those London streets that you only walk along if you are going to one of the buildings that line the street, or using it as a short cut between Blackfriars, Mansion House and Bank.

The majority of people who come into contact with the street, probably cross the street when walking between the Millennium Bridge and St Paul’s Cathedral.

I have written previous posts about some of the sites alongside Queen Victoria Street, however a couple of my photos from 1982 prompted a walk along the full length of the street, and an attempt to get a better understanding of how the street was built, as one of the 19th century’s major attempts to relieve congestion in the City and provide faster east – west travel.

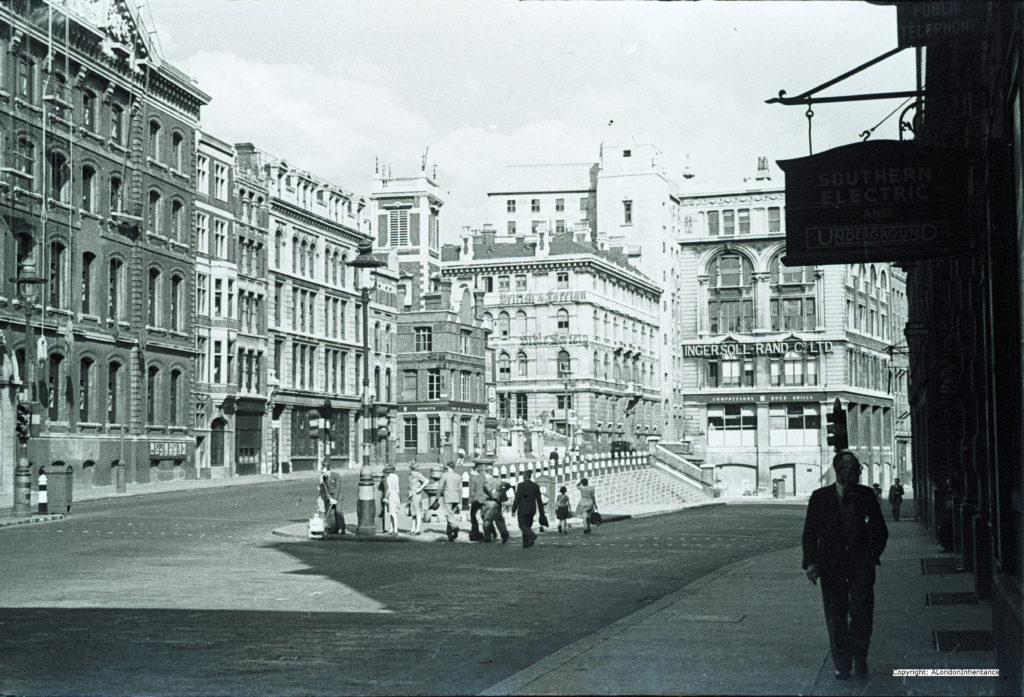

This was the view in 1982, looking up along Queen Victoria Street, with the decorative gates of the College of Arms on the left.

The same view in 2019 (although with some lighting difficulties due to the bright sun from the south).

In the 1982 photo, post war office blocks line the right side of the street, including the Salvation Army building closest to the camera. In the 2019 view, these buildings have been replaced with new buildings which show the change in architectural style that has predominated all recent City development, where a stone facade with windows has changed to a facade mainly of glass.

In the distance in 1982 is the office block that would later be replaced by 20 Fenchurch Street, the Walkie Talkie building seen in the 2019 photo.

The pavements on each site of the street have been widened and the letter box moved out further.

Looking down along Queen Victoria Street from roughly the same position, towards Blackfriars in 1982:

The same view in 2019 – not that much change really.

Opposite is the church of St Benet’s:

I explored this church a few years ago in my post on “The Lost Wharfs of Upper Thames Street and St. Benet’s Welsh Church” and also the excavations of Baynard’s Castle and Roman foundations just south of the church.

The church today:

Queen Victoria Street was built to provide a wide and direct route from the major junction at the Bank and Mansion House directly down to Blackfriars Bridge and the Embankment.

In the following map extract, Queen Victoria Street is the street running from the junction at upper right, down towards Blackfriars Station and Bridge at lower left (Map © OpenStreetMap contributors).

The construction of Queen Victoria Street resulted in the demolition of numerous buildings and streets. The book “A Dictionary of London” by Henry Harben (1918) provides a good description of the impact of the street:

“Construction recommended 1861 and provided for in Metropolitan Improvement Act, 1863. Opened 1871. Nearly two-thirds of a mile long.

Numerous courts and alleys, as well as streets of a larger extent, were swept away for its formation. Amongst those which had occupied the site previously were Five Foot Lane, Dove Court, Old Fish Street Hill, Lambeth Hill (part), Bennet’s Hill (part), St Peter’s Hill (part), Earl Street, Bristol Street, White Bear Alley, White Horse Court.

Considerable difficulties were experienced in the formation of the street owing to the steep gradients from Upper Thames Street to Cheapside. In some cases the existing streets had to be diverted in order to give additional length over which to distribute the differences in level. The net cost was over £1,000,000. Subways for gas and water were constructed under the street and house drains and sewers below these.”

There is no doubt that the new street was needed to support the ever-growing volume of traffic across the City, but all those lost names, although the remains of some can still be found. For example, Harben mentions Five Foot Lane. This is a name that in various spellings dates back to at least the fourteenth century with the first record of a Fynamoureslane. Later spellings included Finimore Lane, Fine Foote Lane, Fyve Foote Lane, Fyford Lane and Fye Foot Lane.

It is with this latter spelling that the lane can still be found – a narrow alley between new office blocks that leads from Queen Victoria Street down to Upper Thames Street.

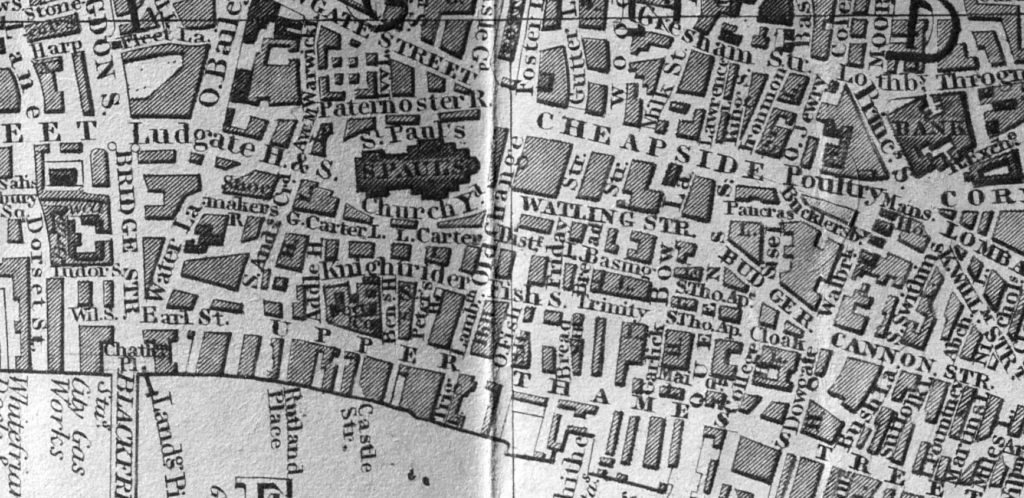

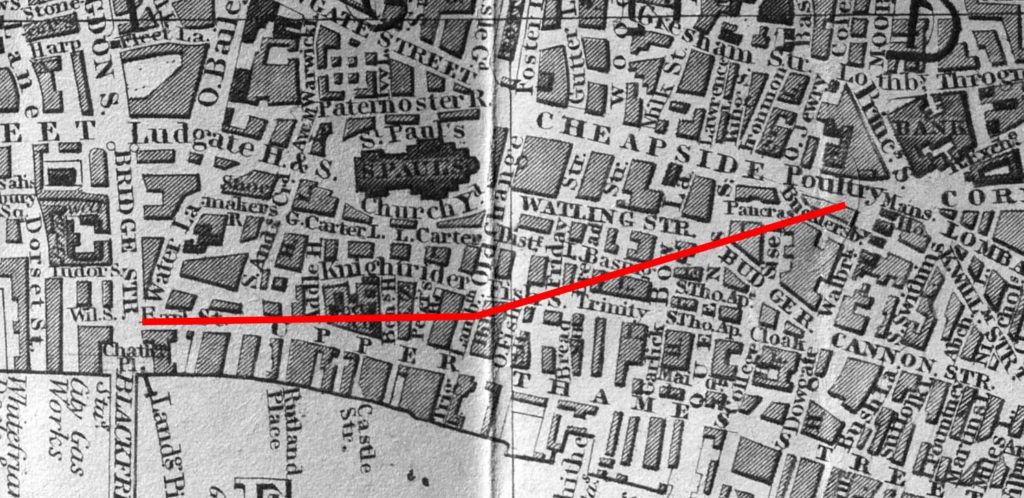

The following extract from the 1847 Reynolds’s Splendid New Map of London shows the area where Queen Victoria Street would later slice through the middle.

I have tried to show the approximate route of Queen Victoria Street by the red line in the following map:

The name of the new street, after Queen Victoria, was agreed in December 1869 when a meeting of the Metropolitan Board of Works were presented with a report recommending the name.

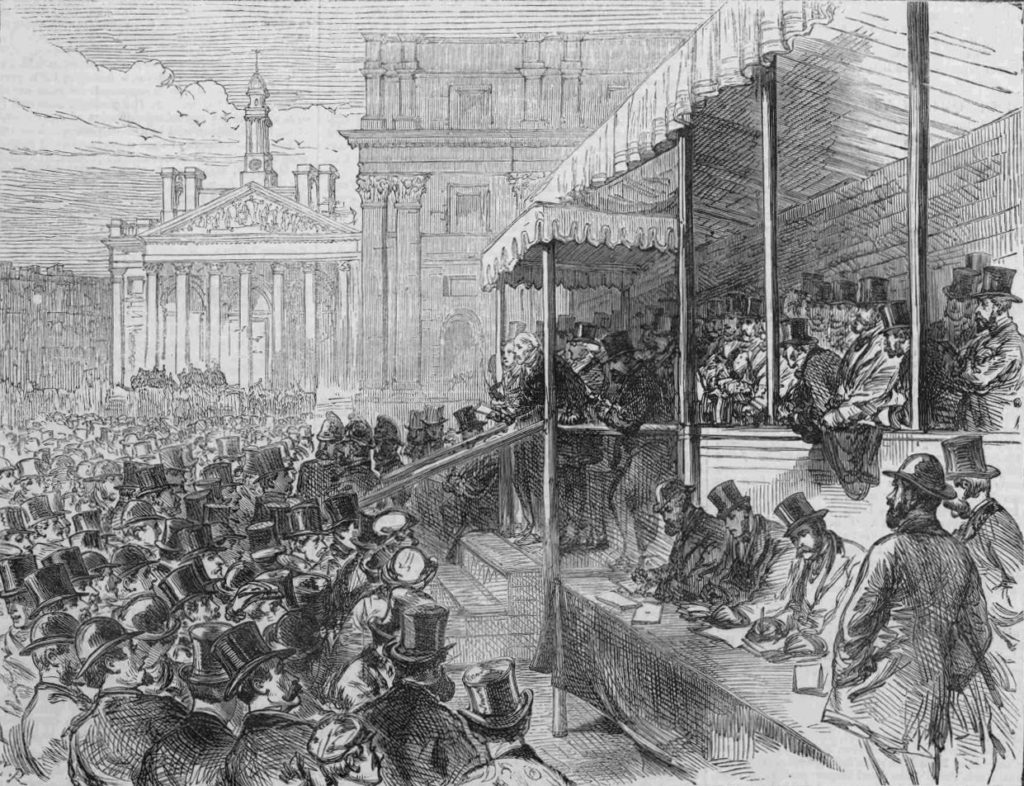

The Illustrated London News described the opening of Queen Victoria Street in November 1871:

“The ceremony of formally opening this new street, from Blackfriars Bridge to the Mansion House, was performed at half past three o’clock on Saturday afternoon. There was a procession of the officers and some members of the Metropolitan Board of Works and of the Corporation of the City headed by Colonel Hogg, Chairman of the Metropolitan Board, with the Lord Mayor, walking arm-in-arm, the Sheriffs of London and Middlesex, and several of the Parliamentary representatives of the metropolitan boroughs. These walked from Blackfriars, along the newly made roadway from New Earl-street to Bennet’s-hill, which has not hitherto been passable, and thence along the first-made portion of the new street to the Mansion House.

Having arrived at the hustings erected on the triangular space at the side of the Mansion House, Colonel Hogg and the Lord Mayor briefly addressed the persons there assembled, reminding them of the various City and Metropolitan improvements which had been accomplished during the last ten or fifteen years – the Thames Embankment, the Holborn Viaduct, the rebuilding of Blackfriars Bridge and Westminster Bridge, the opening of Southwark Bridge, the Metropolitan Meat Market, Southwark-street, Garrick-street, Burdett-street, Commercial-road, the removal of Middle-row Holborn, The opening of Hamilton-place, Park-lane, the laying out of Finsbury Park and Southwark Park.”

The above text highlights that Queen Victoria Street had been built and opened in sections, with the lower part down to Blackfriars being the final section (that shown in my photo above looking down towards Blackfriars)

The final paragraph also shows how much change there was in London during the later decades of the 19th century. It was the work during these decades which has shaped so much of the city we see today.

The opening ceremony next to the Mansion House:

It was a brilliant sunny day when I walked Queen Victoria Street – the type of day when even a Victorian street built as a major through route looks fantastic. There are also some fascinating buildings along the street, although only a few buildings date from before the creation of the street.

This building is the Faraday building, once one of the major hubs for international and national telephone circuits and operator services.

The Faraday building is interesting as it is the only building (as far as I am aware), that has components of the first, fully automatic, electromagnetic telephone exchange, carved onto the facade of the building. See my post on the Faraday building for views of these.

South of the Faraday building is this lovely building, currently occupied by the Church of Scientology.

The building at 146 Queen Victoria Street dates from 1866, so was probably built as part of the development of the new street, possibly one of the first new buildings alongside Queen Victoria Street.

The building was by the London architect Edward I’Anson in the classical, Italian style for the British and Foreign Bible Society. The building is grade II listed. I’Anson’s other London works included the Royal Exchange Buildings.

The next building south is one from well before the construction of the street. This is the church of St Andrew by the Wardrobe:

The church is at a higher level to the street. The extract from Harben mentioned one of the difficulties with construction of the streets being the steep gradient down to the river, and it is at places such as the church where this is still visible. The surrounding land could be leveled off towards the street, but this was obviously not possible with the church.

This end of Queen Victoria Street has always been a centre for Post Office / British Telecom infrastructure. The Faraday building being one of the first examples, and across the road is Baynard House, the 1970s brutalist offices and equipment building, built for British Telecom.

Baynard House is built on part of the site of Baynard Castle, hence the name.

Looking up along the facade of Baynard House:

The design of Baynard House included the post war concept of raised pedestrian walkways, separating pedestrians from streets and traffic. There is a rather underused walkway through Baynard House into Blackfriars Station.

In all the times I have used this route, I have not seen anyone walk to and from the station. It mainly seems to be used by smokers and those taking a break from the surrounding building.

Part of the walkway includes a large open space, with the rather intriguing state of the Seven Ages of Man, by Richard Kindersley from 1980.

The sculpture is based on the Shakespeare monologue from As You Like It, which begins with “All the world’s a stage” and then goes on to chart the stages of life from an infant to the point at the end of life where a person is “Sans teeth, sans eyes, sans taste, sans everything.”

Along the walkway there are views to Queen Victoria Street and down to the River Thames. The following photo is from the walkway looking along Castle Baynard Street.

The empty corridor leading up to Blackfriars Station:

The benefit of a raised walkway is that there are some different views than would be possible at street level. This photo looking across the junction of Queen Victoria Street and Puddle Dock, to St Andrew by the Wardrobe and St Paul’s Cathedral.

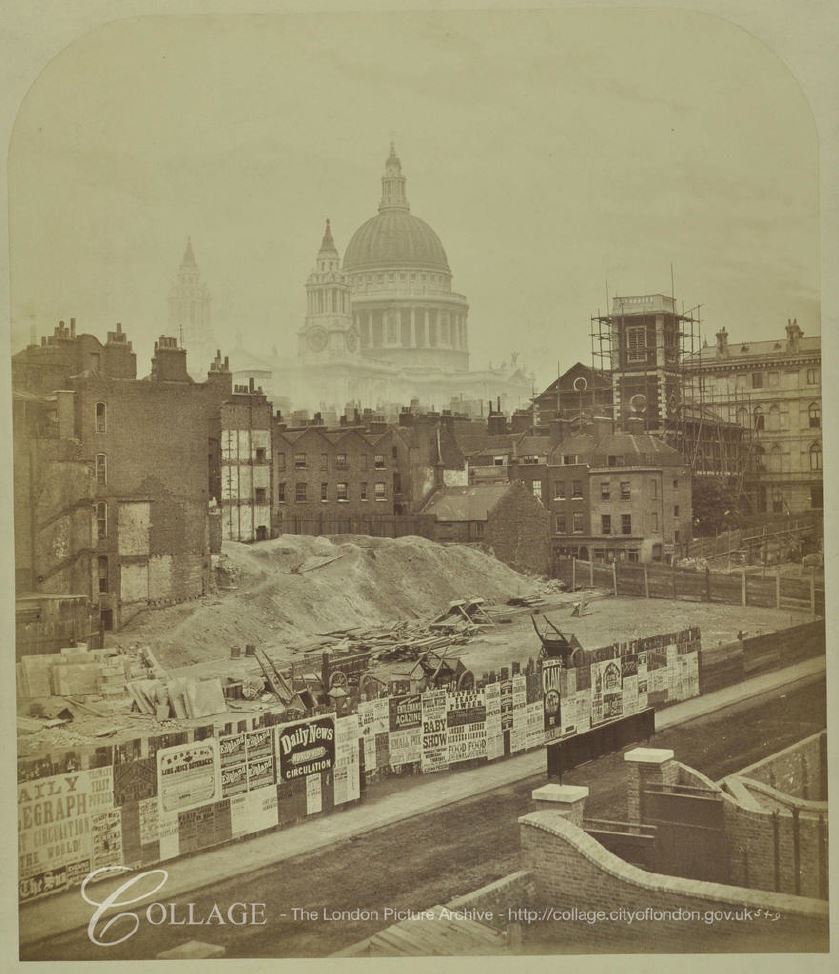

By chance, I found the following photo of the construction of Queen Victoria Street taken from a similar position. I should have been a bit further south, but there were no viewpoints, so the above photo is as close I could get.

Image credit: London Metropolitan Archives, City of London: catalogue ref: SC_PZ_CT_02_1067

From the photo it looks as if a narrow section of street was open (this may have been the original Earl Street), whilst the main part of Queen Victoria Street was constructed.

In front of the church tower are some of the original buildings at the lower end of St Andrew’s Hill. These would later be replaced by the brick building facing onto the new street shown in my photo from the walkway.

There have been some major changes in the southern end of Queen Victoria Street since the original construction. The following photo is one of my father’s photos which I featured in one of my early posts.

The photo shows the original southern end of Queen Victoria Street, with Upper Thames Street merging from the rights.

The following photo from the 2014 post shows the same scene.

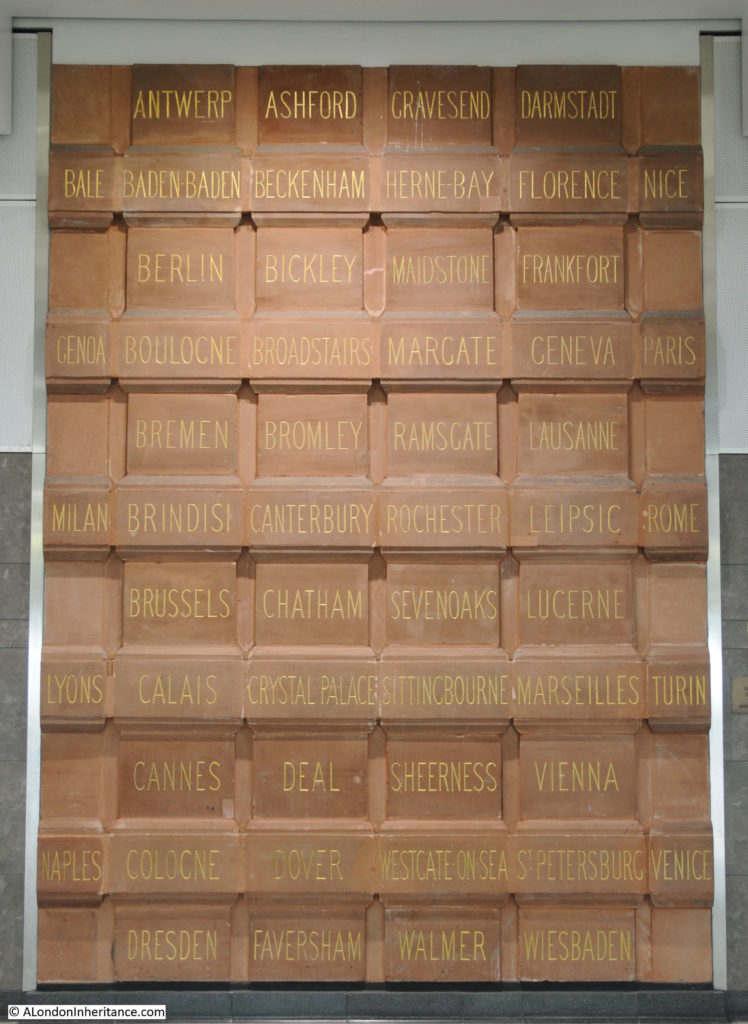

The pedestrian walkway ends up in Blackfriars station, but I had lots more to see in Queen Victoria Street, so it was down the stairs and back out onto the street, but not before admiring the destination panels from the original station.

These stone panels date from 1886, and were replaced in their current position after development work at the station.

The panels show continental destinations that were accessible from the station via a channel ferry. I love how very different destinations are next to each other: Herne Bay and Florence, Sheerness and Vienna, Westgate on Sea and St Petersburg.

Back out of the station and opposite the southern end of Queen Victoria Street.

Marked by one of my favourite central London pubs – the Black Friar:

The Black Friar was built around 1875, so not long after Queen Victoria Street opened. The pub was Grade II listed in 1972, which probably explains how the pub has survived the development of the area. The triangular shape of the building is down to an original street and the new street.

To the left of the pub is a short stub of a street leading to a dead-end. On maps this is currently named as Blackfriars Court, but was originally Water Lane. The plot of land originally extended further south to make a more rectangular plot, however Queen Victoria Street sliced through the lower part of this plot and created a triangular plot on which the Black Friar was built.

The Black Friar was not open yet, and I still had the northern part of Queen Victoria Street to walk, so I headed back to the location of my 1982 photos.

The edge of the College of Arms building appeared in my 1982, today much of the building was covered in sheeting to protect some restoration / building work.

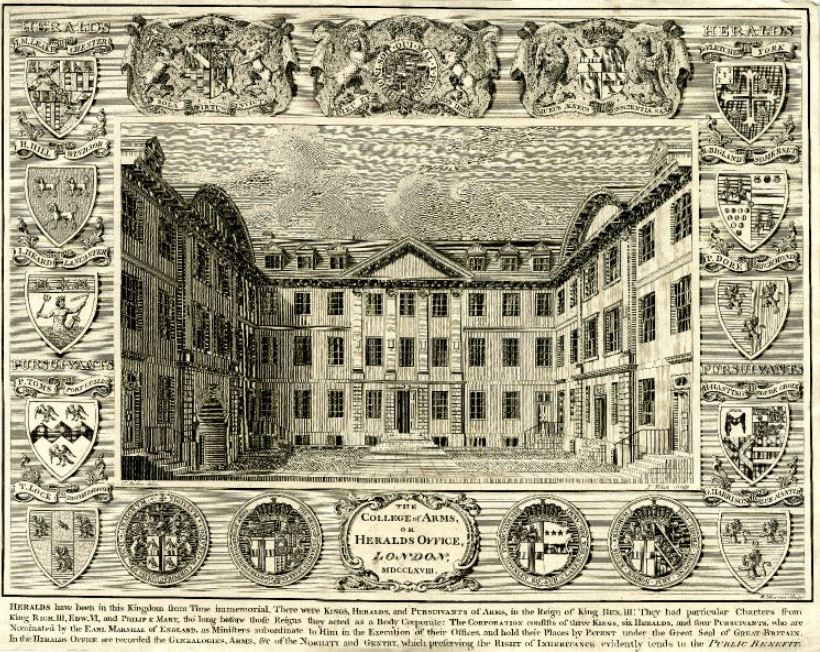

The College of Arms was also impacted by the construction of Queen Victoria Street. Initial proposals for the route of the street called for the demolition of the whole building, however protests by the College Heralds resulted in the route of the new street moving a bit further south.

However even with the new route, parts of the two wings of the College of Arms were demolished, and the building was remodeled as a three-sided building, with shorter wings down to the new Queen Victoria Street.

The College of Arms building dates from after the Great Fire of London when the original building was destroyed.

The following print from 1768 shows the building before the late 19th century changes.

A short distance to the north is the place where St Peter’s Hill crosses Queen Victoria Street. During the day this is a rather busy crossing being on the direct tourist and walking route from the Millennium footbridge across the Thames up to St Paul’s Cathedral.

The view looking north:

And the view looking south with the chimney of Tate Modern / Bankside Power Station just visible.

At the point where the southern approach of St Peter’s Hill reaches Queen Victoria Street, there are a pair of steel gates.

I had not realised this before, but there is a name carved into the lower section of the gates which identify them as the HSBC Gates – presumably after the company that paid for them.

They were designed by the artist Sir Anthony Caro and installed as part of the development of the walkway at the time of the build of the Millennium Bridge,

A 2012 report by the City of London, Streets and Walkways Sub-Committee identified a number of problems with the walkway between the Millennium Bridge and St Paul’s, and with maintaining the gates:

“Not originally designed and set out to deal with the numbers of people now using it,

this area has suffered a noticeable decline in the local environment since the

Millennium Bridge opened. The HSBC gates are often used for graffiti and urination

and require frequent cleaning and sticker removal.”

The point where St Peter’s Hill crosses Queen Victoria Street is probably the busiest point on the street.

Further north along the street is the church of St. Nicholas, Cole Abbey.

A church has been on the site since at least the 12th century. The church was badly damaged during 1940, along with much of the area south of St Paul’s Cathedral.

My father took the following photo in 1947 looking across Queen Victoria Street with the shell of the church (from my post on St Nicholas, Cole Abbey):

Across the road from the church are Cleary Garden’s:

The gardens are not built on the site of a lost church or churchyard, as so many other City gardens. They are built on the site of houses destroyed during the Blitz. The garden was created by a shoemaker called Joe Brandis who started the garden in the rubble of destroyed buildings.

The name comes from Fred Cleary who was Chairman of The Corporation of the City of London’s Trees, Gardens and Open Spaces Committee for three decades prior to his death in 1984.

Fred Cleary’s involvement with the City of London Corporation resulted in many of the gardens that we see across the City today. He was a firm supporter of the need to create and maintain green spaces across the City, and as with the garden’s that carry his name, made good use of the many bomb sites, some of which had already the foundation of a garden, such as that created by Joe Brandis.

I have now reached the junction of Queen Victoria Street and Cannon Street. The tower is that of the church St Mary Aldermary.

Street name sign and boundary markers. the one on the left is unusual in that it has the names of the church wardens engraved presumably from the date of the marker in 1886.

Crossing the road junction and looking back along Queen Victoria Street, and on the right, between the street and Cannon Street is the distinctive form of 30 Cannon Street.

30 Cannon Street dates from 1977 and was by the architectural partnership of Whinney, Son and Austen Hall.

The building fits into a triangular plot of land – probably that shape after the creation of Queen Victoria Street cut through the lower triangular section of what had been a rectangular plot of land.

The shape of the windows, the rows of windows leading to the curved section facing onto the street junction, and the brilliant white of the material all help make this a stunning post war building.

The panels surrounding the windows are made from glass fibre reinforced cement – the first building to use this material.

If you also look along the sides of the building, it appears to bow out towards the street. which is down to the 5 degree outward lean of each window section.

Floors 1 to 4 have the window arches at the top of each window, but look at the top floor and the arch is upside down with the side legs of the arch around each window facing upwards.

The building is Grade II listed, the justification being the design, usie of innovative materials and the way in which the building integrates with the remaining Victorian buildings around the junction – a justification with which I fully agree.

I have now reached the northern end of Queen Victoria Street, where the street runs up to the major junction by the Mansion House and Bank of England.

The building in the photo below is the City of London Magistrates Court with the address of 1 Queen Victoria Street, so the street starts here.

This was the location of the opening ceremony shown in the print earlier on in this post. In both photo and print, a corner of the Mansion House can just be seen.

And in the photo below I am at the very end of Queen Victoria Street, looking towards the heart of the City, and the major junction where Lombard Street, Cornhill, Threadneedle Street , Princes Street and Poultry all meet.

Standing here, the need for the construction of Queen Victoria Street becomes clear. The street provides a direct route from the heart of the City to the station at Blackfriars, and for traffic it also offers a quick route across the river via Blackfriars Bridge, and to the west along that other Victorian engineering marvel, the Embankment.

However it is also a sad loss of all the small streets and alleys that once covered this section of the City, and were swept away by Victorian improvements. Also the archaeological remains that may have been lost as I suspect the Victorians were more interested in getting the street completed, than investigating what lay below the ground.

Re The Salvation Army building at 101 Queen Victoria St.

The first international headquarters was established in 1880 in Whitechapel Road, and moved to Queen Victoria Street in 1881. Destroyed by fire during the Second World War, the IHQ building was rebuilt and opened by Queen Elizabeth, the Queen Mother, in November 1963. Following a brief residency at William Booth College, Denmark Hill, in the early years of the 21st century, the International Headquarters returned to its Queen Victoria Street site and the new building was opened by Her Royal Highness The Princess Royal in November 2004.

Queen Victoria Street has always rather perplexed me – the Blackfriars end with the appalling 70s architecture doesn’t seem to make any sense whilst further east it is easier to see how it fits in with older street planning. I recall walking along one Saturday morning in early 1977, just me on a practically deserted roadway that was undergoing massive re-building. On the other hand, I have always loved 30 Cannon Street and, if a bit lost, use it to orientate myself in the busy traffic. I would have loved to see the older streets that were swept away by the Victorian developers, especially Budge Row. Very pleased to see the stub of Water Lane, that ancient path. Was very busy studying old plans and maps of Blackfriars monastery this week – like you do, obvs – and you can see this quite clearly. Next time I am waiting at the lights there I will pop up and take a closer look.

Fascinating survey of, as you say, a somewhat neglected area, and of what you can find if you go looking. I’m interested in this because two of my great-grandparents lived in a tenement building in Sugar Loaf Court, off of Garlick Hill, one of the courtyards demolished for the new street. Not that it was a great loss I suspect, because looking at the 1861 census, my ancestors William and Louisa Newman and their family of three daughters were just one of many families living in two rooms of the same tenement – the City had many more working class families living in it in then. Thanks again for my Sunday morning read!

Thank you for another fascinating article about a road I’ve walked along but not, until now, taken too much notice of. And thank you for both post war photos and your photos from 1982 being included in your research as well as the current, modern-day, images.

Great Sunday evening read

Yet again a great Sunday read. So many old streets gone. Modern glass boxes set to dominate now and in the future.

It’s interesting to see the number of acutely angled buildings, resulting from the original plots being sliced up by the construction of the street, and how they are generally rather more attractively styled than the average building. One thing that has changed in the view of the west end of the street is that the north end of the railway bridge was lowered by around one metre in 1990, as the project to divert and lower the Thameslink/Holborn Viaduct route needed this drop to slightly ease the steep gradient on the new vertical alignment down to St Paul’s Thameslink station (renamed City Thameslink a year or two later). The bridge is still the same deck as in the first picture, despite appearances, having had new parapets attached at a later date.

As I recall, there are two pairs of HSBC gates, one larger pair by the road, and a smaller pair nearer the bridge. The 2012 reports also complains that they are an obstacle!

In the first photo, the building beyond the Salvation Army HQ is Walker House. A relic of the failed Slater Walker empire, towards the end of its life, 1990s, it was partially occupied by the Museum of London Archaeology Service, who had a habit of occupying buildings towards the end of their life. The basement was a finds store, photo studio and very dodgy drinking club, the name of which eludes me.

Roy,

You suggest that Walker House, which stood at 95 Q V St, was connected with Jim Slater’s failed empire. Actually, it was named after the unrelated textile merchanting company Walker and Rice, founded by my grandfather S.R.(‘Johnny’) Walker 1892-1989 and his brother-in law Billie Rice, after the First World War. As a Common Councillor, Johnny Walker persuaded the City Corporation to grant him a 99yr lease on the site and built Walker House in the early 1960s to house his company, with warehousing for cloth in the two basements, which provided easy loading access at the back on Lambeth Hill. I started work just off Cannon St in the late 1970s and we often saw men in warehouse coats emerging from the alley of Gt St Thomas Apostle next to Mansion House tube station carrying a sheaf of mink skins over their shoulder: clearly, trade in physical goods in the Square Mile continued for many years after W.War 2.

It is ironical that with the advent of computers in offices, most of those 1960s office buildings, built with low ceilings and central heating, have been demolished long before some Victorian structures nearby. The high ceilings of those grand old buildings can accommodate the installation of air conditioning systems to keep an office tolerably cool, even with modern office equipment humming on every desk. For the low ceiling’d 1960s buildings, the demolition ball is usually the only means of modernisation.

Interesting post. I worked at Walker & Rice in the office as a receptionist in around 1978. It was a great company to work for and I have happy memories of my time there.

A most interesting and well- researched article – thank you. I lived in No.146 from 1941 to 1963 – my parents were housekeepers there. The devastated areas were our playground. I was also articled to the Salvation Army HQ Architect Hubert Lidbetter and worked on its design. I have stories galore of the area in those days; I still practice and am a member of the Castle Baynard Ward Club.

Fascinating, my grandparents lived in 123 queen Victoria street, they were the cartakers of an office block, they lived on the top floor. Me and brother would go up there every year to stay with them, back in the 1950-60s, have many enjoyable memories of my time there, playing around upper Thames street and along the Thames (tide out) my grandfather was also the curator of St Benents church. He was also a fire watcher during the blitz, there is a photo of the building near them collapsing in flames in Queen Victoria street after a night of bombing. The bomb sight was where we used to play, got over run with wild cats in the end,

Back in 1954 – 1955 I worked for the Muldivo Company, which was located on Queen Victoria Street (I think that it was #48), a building which had survived the bombings. My Father worked at St. Paul’ s Cathedral , and I would walk to the Cathedral after work to drive home with him. I had moved to California before the reconstruction, and now know why members of the family told me that I would be most unhappy with the changes to the places that I knew so well.

Hello. This article was interesting and helpful. My great great uncle George E Stone visited London in August 1898 on his way to Arabia as a missionary. His tours were led by an Elliot Glenny from Barking. George visited the British and Foreign Bible Society Building. Elliot’s father Edward H. Glenny was associated with the North Africa Mission located on Linton Street in Barking. My lineage of Stones was from Great Bromley, arrived in the new world in1635 on the Ship Increase. I’m writing a biography of George, so thank you for the photos and information.

I stumbled on this page after accessing the 1921 census. My maternal great-aunt’s occupation is recorded as being a shorthand typist at a company, Goodrich Hamblyn Ltd., 11 Queen Victoria Street, London EC4.

This was a fascinating read, which I enjoyed immensely, thank-you.

Interesting. My great grandfather is down as being a “Marine Mechanical Engineer” at 11 Queen Victoria Street, EC…

Thank-you Steven, I did try to find out what type of business Goodrich Hamblyn was, without success.

Fascinating I could fill you in on Sweetings Restaurant est. 1889 In Albert Buildings Queen Victoria Street oldest fish restaurant in London. I’m currently writing a small book If you want to meet you know where we are