I am a couple of weeks late with this post, as it should have been towards the end of April to coincide with the opening on the 23rd of April, 1924, of the British Empire Exhibition at Wembley.

A look at the exhibition is interesting as it shows how much has changed in the space of one hundred years. Physical change at a place where London was expanding in the 1920s, change in Britain’s place in the world, and a change in attitudes.

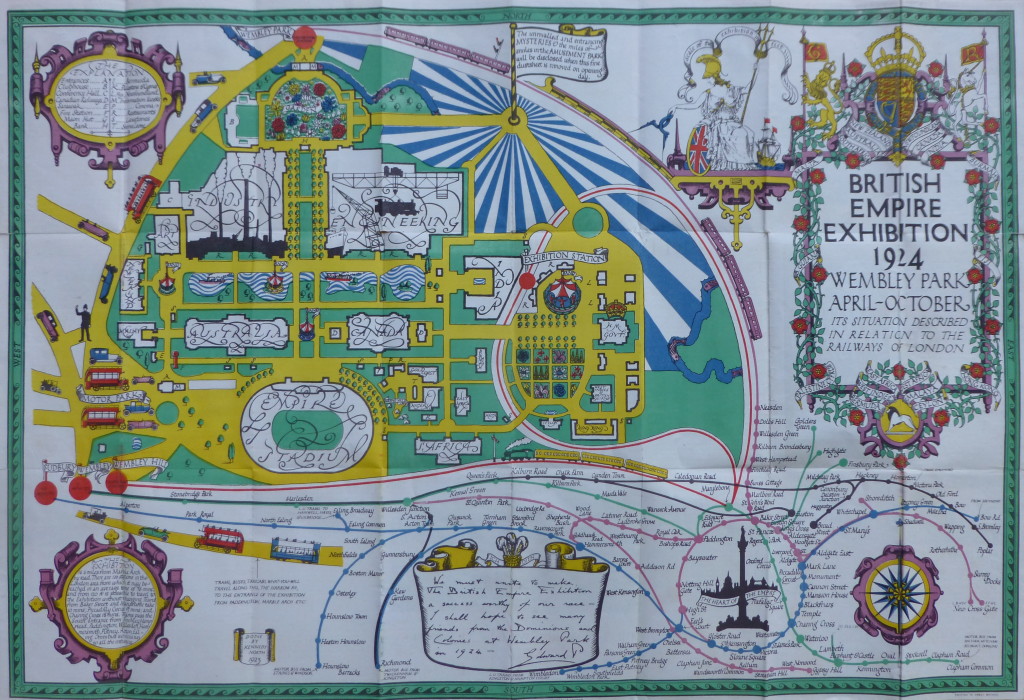

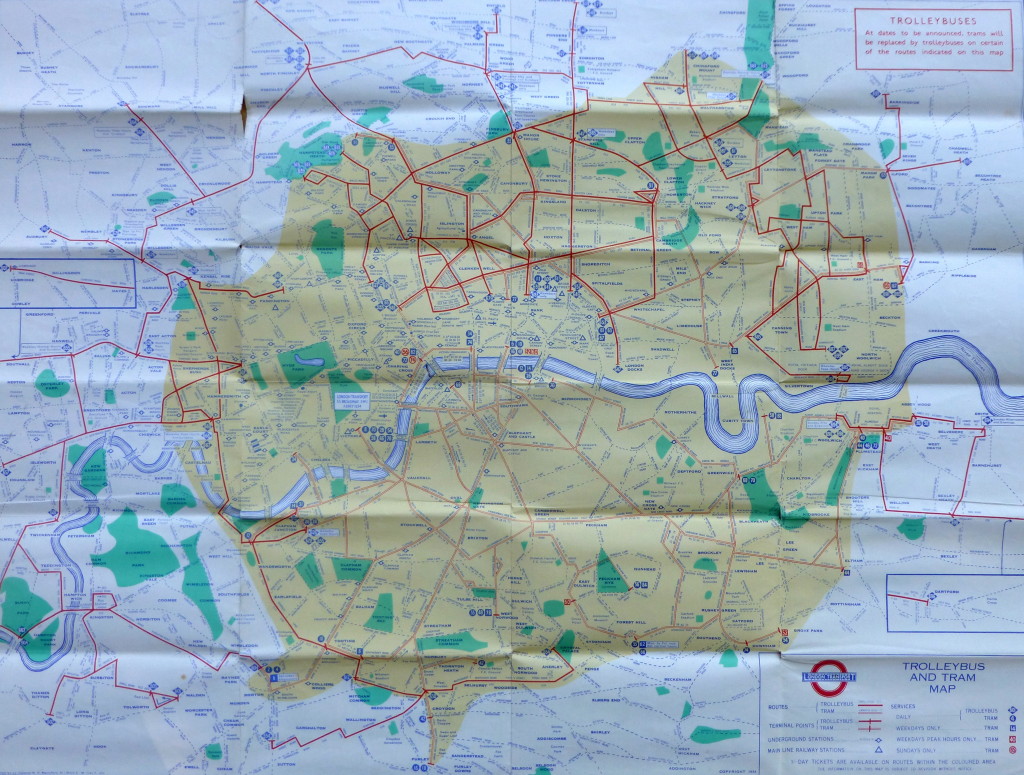

I have a copy of the plan of the exhibition site, and it is wonderful example of mid 1920s graphic design:

The plan was created by Stanley Kennedy North (a small box to lower left states “Done by Kennedy North 1923”).

Kennedy North was an interesting character who worked across a wide range of media including stained glass, maps and advertising posters.

The plan was created 10 years before Harry Beck’s innovative map of the London Underground, which still forms the basis of the map in use today, so Kennedy North portrayed the routes across London leading to Wembley Park in his own style, and across the lower part of the map are the routes and stations that will take the visitor to the stations in Wembley for the exhibition.

The text at the bottom left corner of the plan informs the visitor that “The Exhibition is 6 miles from Marble Arch by road. There are 120 stations in the London area from which it may be reached in an average time of 18 minutes, and from 120 it is possible to travel to the Exhibition without changing. Trains from Baker Street and Marylebone take 10 mins; Piccadilly Circus 15 mins; and Charing Cross 18 mins. Trams pass the South Entrance from Finchley, Hampstead, Paddington, Willesden, Hammersmith, Putney, Acton, Ealing. Omnibus services run to all the entrances”.

Wembley in the 1920s was an area transforming from a rural landscape to a built suburb of London, and many Londoners would probably not have known the area, or visited before, so the travel details in the plan with timings demonstrated how easy it was to reach the exhibition site.

The Wembley site was chosen in 1920, when the Government gave the go-ahead for the exhibition, and it would be built on the site of some pleasure gardens built in the 1890s Sir Edward Watkin.

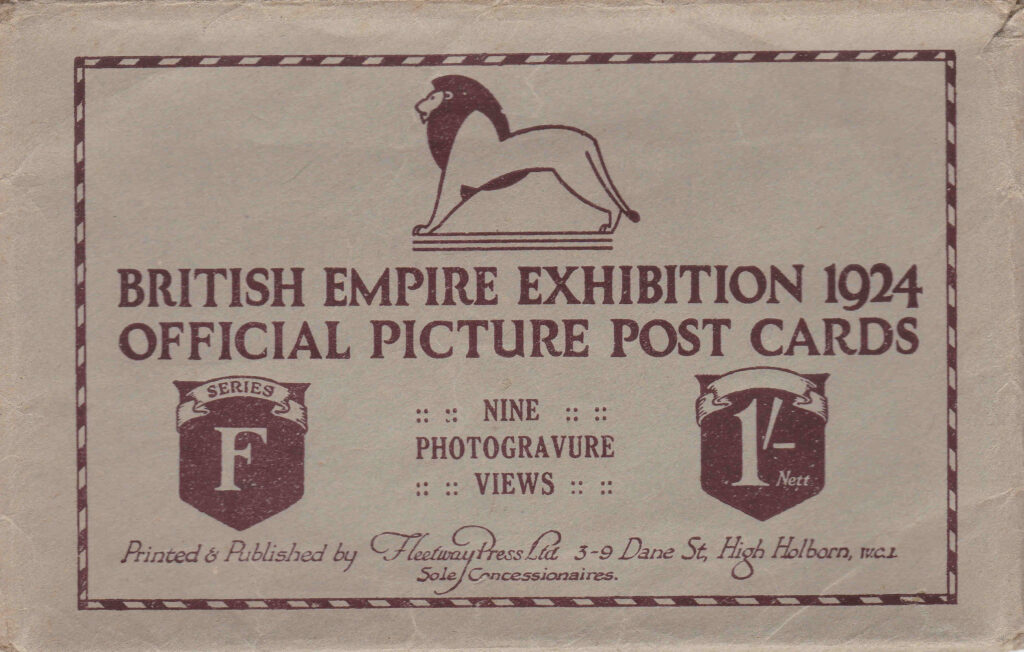

The focus of the 1924 exhibition was the new stadium, which had been built for the exhibition, and would be the site for the opening and closing ceremonies, as well as a wide range of events during the exhibition.

It was intended to demolish the stadium after the exhibition, however it was kept open afterwards and used for major football events, as well as hosting the 1948 Olympics.

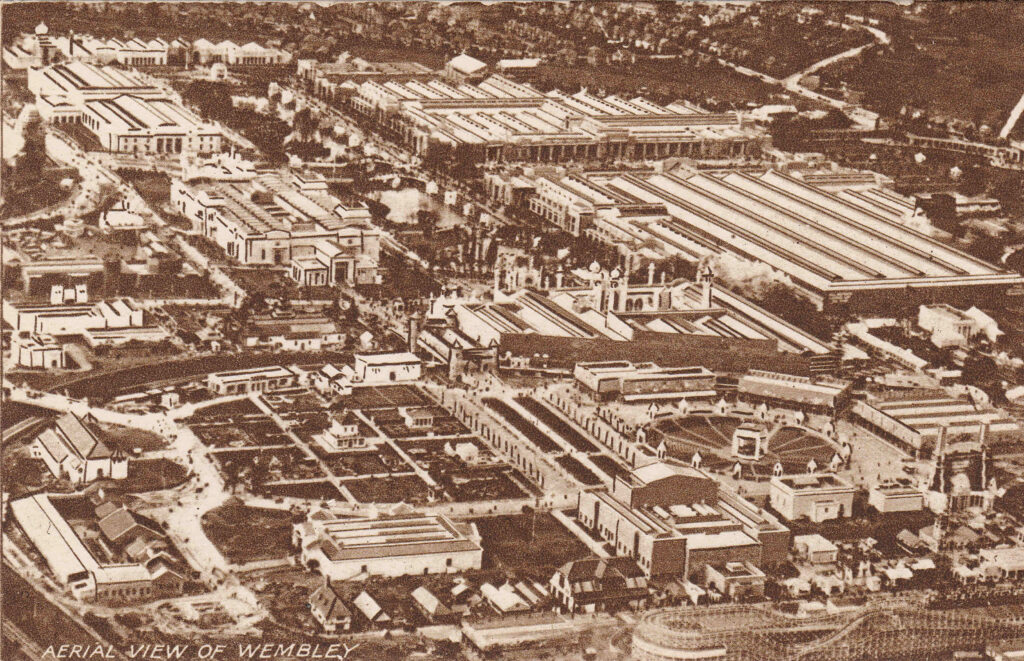

The Britain from Above website has a number of photos showing the site, with the stadium to the south, built alongside the railway, and the Empire Exhibition site around the east, west and running north of the stadium:

Source: https://www.britainfromabove.org.uk/image/EPW010737

The idea that the stadium was intended as a temporary structure may seem remarkable given the size and construction effort, however a glimpse of the overall site as shown in the above photo gives an indication of how much building work was required to complete the exhibition site.

This was also a time when Wembley was transforming from a rural landscape of fields, hedges. trees etc. into a fully built part of the wider London.

The following photo of the exhibition, looking to the east shows that fields were still surrounding much of the overall exhibition site. The tracks of the railway which would facilitate much of the development of the land can be seen to the right of the stadium, and along the northern edge of the site, splitting off at Neasden which would be at top right:

Source; https://www.britainfromabove.org.uk/image/EPW010844

Britain from Above dates the following photo of the stadium to 1923, and again it shows how rural Wembley was, one hundred years ago:

Source: https://www.britainfromabove.org.uk/image/EPW008545

This photo is looking north, with the very first stages of construction of the new stadium. The photo is dated 1922, and the trees in the photo appear to be in leaf, so if 1922 is correct, then the stadium would be built in less than a year which seems remarkable if the date is correct:

Source: https://www.britainfromabove.org.uk/image/EPW007831

The aim of the 1924 Empire Exhibition was to demonstrate and celebrate Britain’s place in the world, along with the British Empire which was portrayed as “Co-operation Between Brothers”.

The exhibition was opened on the 23rd of April, 1924 by King George V. Some excerpts from his opening speech serve to show some of the thinking behind the exhibition:

“The Exhibition may be said to reveal to us the whole Empire in little, containing within its 220 acres of ground a vivid model of the architecture, art, and industry of all the races which come under the British Flag.

It represents to the world a graphic illustration of that spririt of free and tolerant co-operation which has inspired peoples of different races, creeds, institutions, and ways of thought to unite in a single commonwealth, and to contribute their varying national gifts to one great end.

This Exhibition will enable us to take stock of the resources, actual and potential, of the Empire as a whole; to consider where these exist and how that can be best developed and utilised; to take counsel together how the peoples can co-operate to supply one another’s needs and to promote national well-being.

It stands for a co-ordination of our scientific knowledge and a common effort to overcome disease and to better the difficult conditions which still surround life in many parts of the Empire.”

The speech demonstrated a very paternalistic view of the Empire, and that the focus of the Empire was on the common good, but the sentence that “of all the races which come under the British Flag”, and the comment that the exhibition will “enable us to take stock of the resources, actual and potential, of the Empire as a whole”, demonstrate why the Empire was considered important to the country, and Britain’s place in the world.

Built to the north, and around the stadium were a whole series of buildings and pavilions, as well as a lake.

The buildings and pavilions were each dedicated to a specific country or region in the Empire, as well as two large buildings, one each for Industry and Engineering, and a smaller building for Art.

The size of the country buildings perhaps illustrates the relative importance at the time of each, with large buildings for Australia, Canada and India, and smaller buildings for South Africa, East Africa, the Gold Coast etc. down to Malta which appears to have had the smallest building on the site.

Each of these buildings featured displays from the country, customs, resources, products and people, and many of the country buildings included indigenous people demonstrating some of their local crafts. Looking at some of the film from the exhibition and it is hard to see these indigenous people as being just part of the exhibits on show to the visitors to the exhibition.

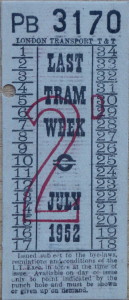

If you were a visitor to the 1924 British Empire Exhibition then you may have wanted to return home with a souvenir, and some of the most popular were a range of postcard packs showing various scenes from the exhibition.

I have a couple of these, and they show what it would have been like to walk around the exhibition, and to appreciate the substantial scale of the exhibition which had been built on a green field site in a couple of years.

The first shows the approach to the Empire Stadium as it was named for the exhibition, with the twin towers on either side of the main entrance. Of the two buildings in the lower part of the photo, the Australian pavilion is on the right, and that of Canada on the left:

The first game of football hosted by the Empire / Wembley Stadium was in the year before the exhibition, when the 1923 FA Cup Final was held between Bolton Wanderers and West Ham, and which Bolton went on to win 2 – 0. The stadium had only just been completed and there was some doubt whether it would be ready in time. The Football Association were though keen to stage the event in the new, large stadium.

The result was crowds of much higher numbers than the stadium could accommodate, and scenes of chaos before the match could be completed.

The stadium had been built for 127,000 people, however the numbers that crammed in to watch the final were anywhere between 200,000 and 300,000. There were too many to make an accurate count, and the higher number was the estimate by the Police.

Headlines from the following day given an indication of the problems at the stadium, for example, from The People (London, Sunday April 29th 1923):

“1,000 Casualties at the Cup Final, Mob Overruns the Ground, Barriers Stormed and Pitch Invaded, Unparalleled Scenes, 200,000 Crush into Space For 127,000, Mounted Police 40 Minutes Tussel, F.A, Disclaim Responsibility.

Scenes without parallel in the history of football occurred at Wembley Stadium yesterday when mob-law spoiled the match for the Cup between West Ham United and Bolton Wanderers, which the latter won by two clear goals.

Crowds swarmed onto the playing pitch and for some time perfect chaos reigned. It is estimated that about 1,000 people were treated for minor injuries. mounted police were sent for, and they had to be used to clear the ground, the players themselves doing their best to persuade the unruly spectators to give them sufficient space to play the game.

Eventually, after wild scenes, the teams managed to begin the match, but even then the crowd persisted in interrupting play, and at one period the game had to be suspended for 12 minutes while the pitch was again cleared.

Mr. F.J. Wall, Secretary of the F.A, made the following statement – The F.A. greatly regret the inconvenience caused to the spectators during the match, but can assure the public that the arrangements were not in their hands and that they cannot, therefore accept responsibility.”

The F.A, were indeed correct, as the responsibility for managing the stadium during the F.A. Cup Final had been transferred to the management of the British Empire Exhibition, who do not seem to have been prepared for such a large, public event being held at the site, much of which was still under construction.

The following photo is from the 1920’s books Wonderful London, and although it is not dated, it may show the 1923 FA Cup Final:

The crowds and numbers on the pitch are similar to the newspaper reports, and there seems to be little building around the stadium, which would have been the situation in April 1923, one year before opening of the Empire Exhibition.

The postcards continue to show the site in detail. The following photo is looking to the north west, and the two large buildings in the upper right corner are the Industry Pavilion (top) and the Engineering Pavilion (below and to the right):

Industry and Engineering focused on Britain’s expertise and capabilities in these areas, and a statement from the Gas Industry explains why they wanted to be at the exhibition:

“As you are doubtless all aware, the British Empire Exhibition will be opened at Wembley in April, and the Gas Industry felt it should do something worthy of the Exhibition and of itself on this occasion. The industry is arranging a suitable exhibit, and this Company is contributing its share in providing money for this purpose.

The main object of the British Empire Gas Exhibit will be to show the public the domestic and industrial applications for gas and educate them in all the ways in which gas can serve in the house and in business. I hope that those of you who visit Wembley will not omit to visit the Gas Exhibit in the Palace of Industry.”

With the inclusion of major exhibitions of Industry and Engineering, the 1924 Empire Exhibition was very similar to the 1851 Great Exhibition and the 1951 Festival of Britain.

It is one of the strange trends of the last 50 or so years, how industry and engineering have gone from being an important part of the country’s core capabilities and national pride, to be something that only really gets mentioned now when a factory closes.

Industry and engineering feature on TV in programmes such as Gregg Wallace Inside the Factory and programmes on projects such as Crossrail which often seem to focus on the created tension of “will X activity be finished on time”.

I suspect that much of this was down to the closure of so much industry during the 1970s an 1980s along with the transfer to foreign ownership of so many British industrial and engineering companies.

For a fascinating, but depressing read about how this happened, “The Slow Death of British Industry: A Sixty-Year Suicide 1952-2012” by Nicholas Comfort is excellent.

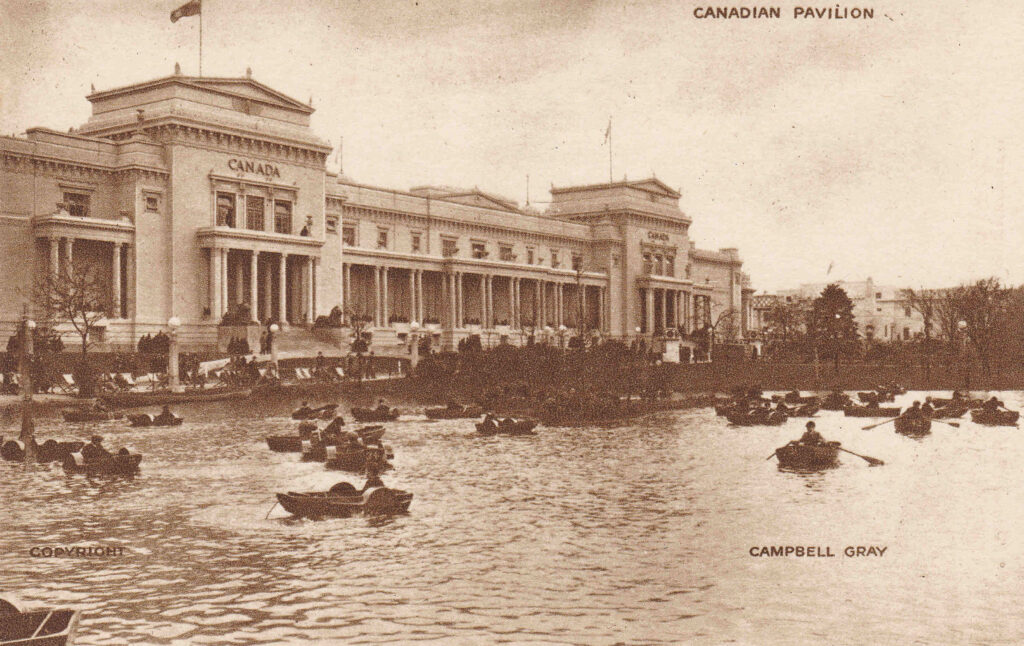

Back to a walk around the Wembley exhibition site, and this is the Canadian building:

The photo shows the scale of some of the buildings at the exhibition, and also shows the boating lake that was set between the Canadian and Australian buildings and those of Industry and Engineering.

Part of the Australian building on the right (Australia had the largest building of all the countries represented at the exhibition), and the building of Malaya on the right:

It was a common theme of 20th century exhibitions that they also had / needed an amusement park. For example, the 1951 Festival of Britain also had the Festival Gardens at Battersea.

The 1924 exhibition was no exception and the following photo shows the entrance to the amusement park:

What was in the amusement park was probably one of the final parts of the planning and build process, as the plan of the site, created the year before, shows the area covered in blue and white stripes, with a flag bearing the text “The unrivalled and entrancing mysteries and the miles of smiles in the amusement park will be disclosed when this fine dustsheet is removed on opening day”.

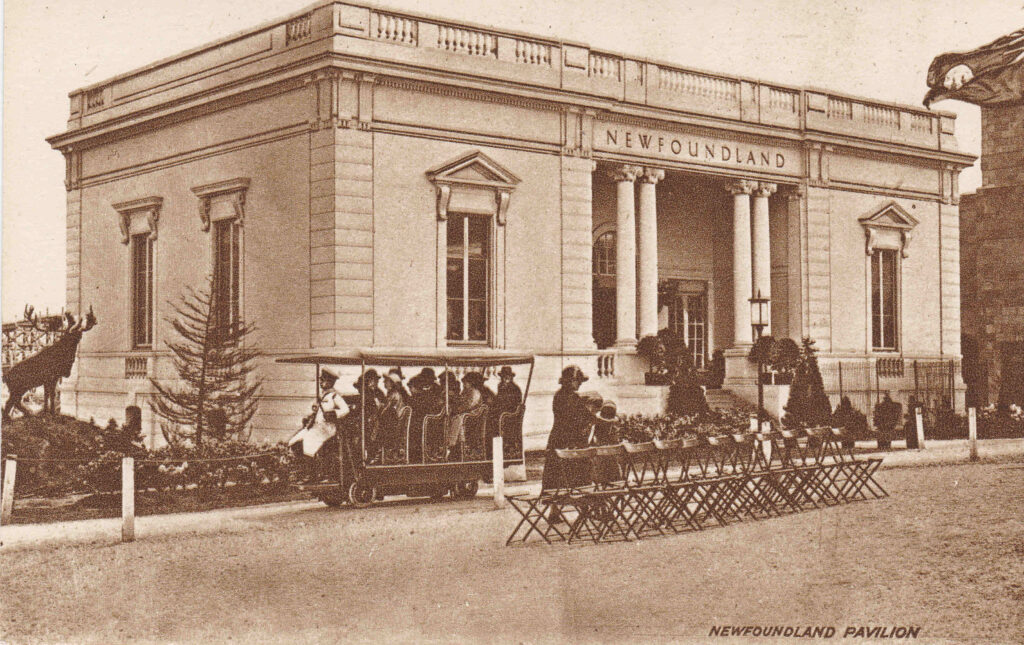

The Newfoundland (part of Canada) Pavilion:

The Burmese Pavilion:

Many of the country buildings, were constructed in the style of traditional architecture from the country concerned, as with the Burmese (now Myanmar) Pavilion shown in the photo above.

Another view of the boating lake:

The Indian Pavilion, along with Australia and Canada was one of the largest pavilions, and was built in the style of grand buildings in India:

The following postcard is labelled the Palace of Industry, however apart from what may be in the display cabinets, there does not seem to be much industry on display:

As well as exploring all the country pavilions, and then going to the amusement park, the stadium was the scene of major events throughout the time of the exhibition.

One such event that ran for a couple of weeks until the 1st of June, 1924 was titled “London Defended” and could be watched in the stadium every evening starting at 8:15pm.

London Defended consisted of: “Two hours of intense yet joyous excitement. Thrill follows thrill, with not one moment of dullness. deeds of daring that claim your admiration and hold you spellbound with the wonder of it, the skilful horsemanship of the Metropolitan Police, the dash and daring of the London Fire Brigade, the breathless exploits of the Royal Airforce, Massed Bands, counter marching to the flickering glow of 200 torches, London Scottish pipers and Highland Dancing; and then the Great Fire of London, giving a fitting finish to an amazing night of adventure”.

Who could resist that for 4 shillings for the best covered seat, down to 6 pence standing on the upper terraces or free on the lower terraces.

Another event featured “a spectacular chariot race”, with six Roman chariots racing abreast. The race was supported by “Hundreds of Performers, Troops of Wonderful Horses, Flocks of Clowns, Marvelous Acrobats, Daring Trick Riders, hers of Elephants, Performing Bears, High Wire Acts, Dare-Devil Raymond in 100 foot Land Dive, Roman Riding, etc. etc.”

In 1924, there was no public television service, the first public radio transmission had only started four years earlier in 1920, and films with sound were not widely available until 1927, also the majority of the population had not travelled outside the country, so this type of entertainment, and the pavilions at the exhibition, would have been a significant and exciting experience for the majority of people.

View along the lake:

The British Empire Exhibition was open between the hours of 10 am and 11 pm, with admission costing one shilling six pence for adults and nine pence for children.

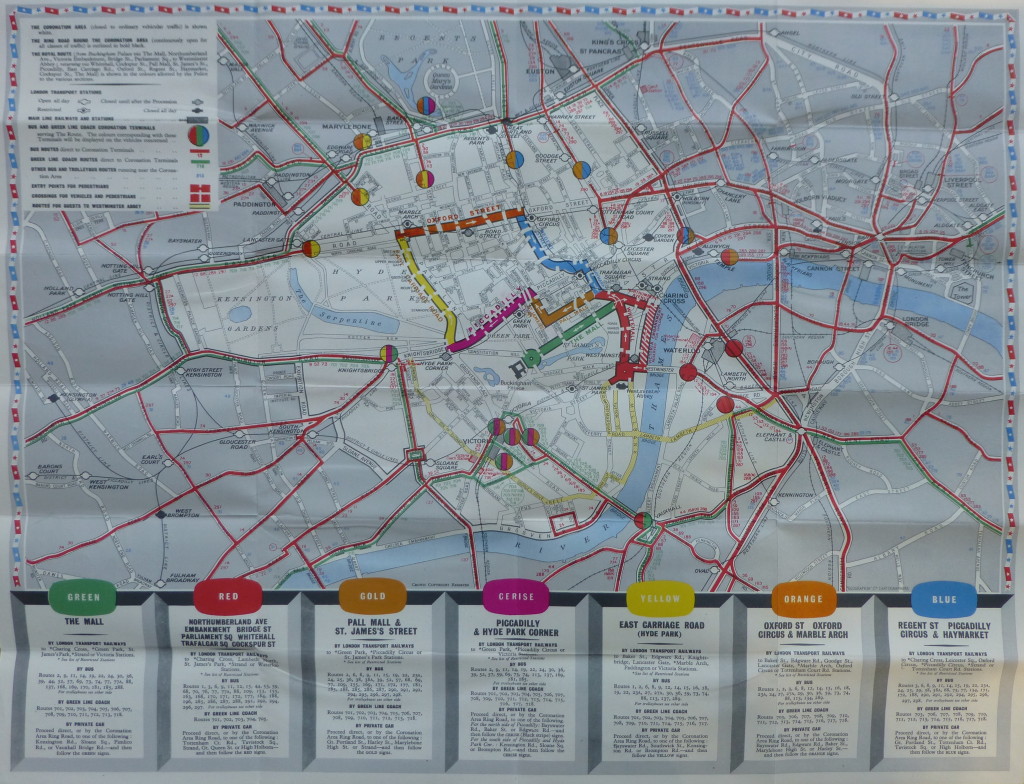

The exhibition was the first major event in London where I have seen specific mention of the car as a means of transport to the event. Publicity material for the exhibition stated “Visitors are advised to park their cars in the B.E.E. Official Car Park ONLY. Accommodation for 2,000 vehicles at popular prices”.

The 1920s were the start of wider car ownership, which would explode after the 2nd World War, and would influence planning for the city over the 20th century.

The Sarawak (a Malaysian state) Pavilion:

The South African Pavilion, which featured along the front a colonial architectural style of a long covered terrace and a colonnade:

The above photo also includes a rather strange means of transport that appears in a number of photos of the exhibition. Obviously motorised, with a driver in the front, and a row of covered seats behind.

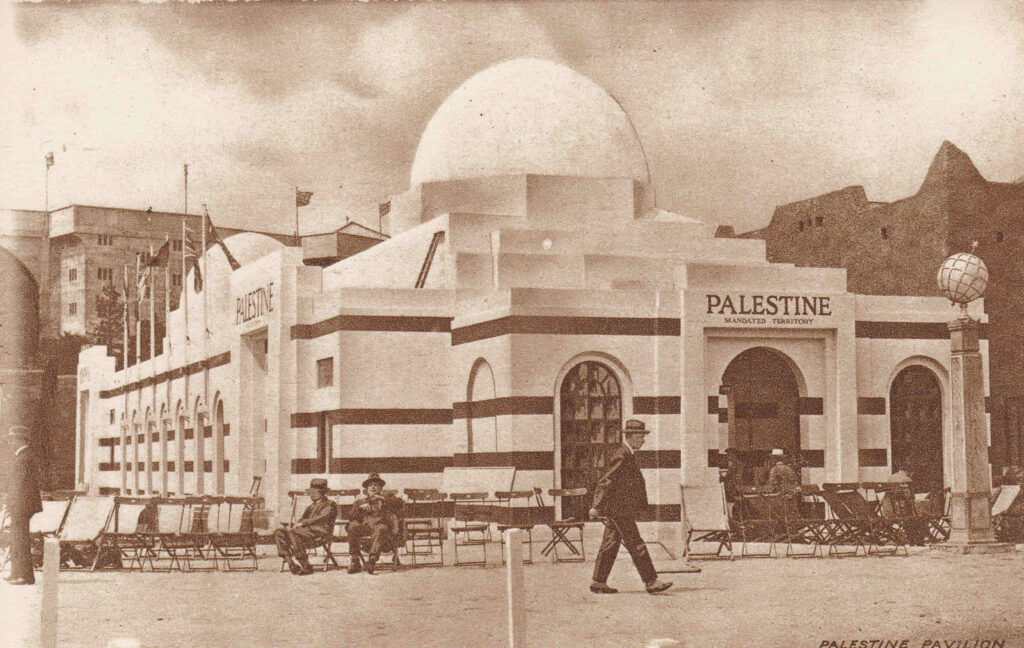

And a reminder of British involvement in the middle east – the Palestine Pavilion:

The New Zealand Pavilion:

The area between all the pavilions was landscaped, as shown in the following photo with the caption of Lake, Gardens and Indian Pavilion:

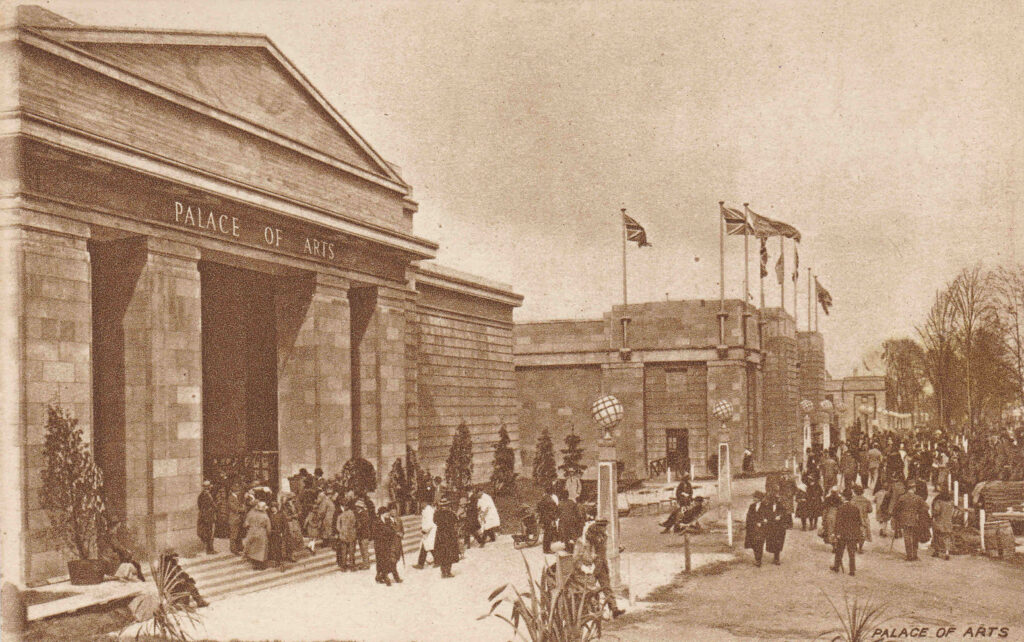

The Palace of Arts:

The Palace of Arts was divided into a number of rooms, including period rooms of 1750, 1815, 1852, 1888, and 1924, rooms covering the art of the theatre, watercolours, oil paintings, sculpture, modern oil paintings and art from India, Burma, Australia and Canada.

The guide to the Palace of Arts introduced the exhibition with “The British Empire Exhibition has for the first time made possible the assembling under one roof of the paintings of today, not only from the United Kingdom, but from every Dominion of the Crown. now first can be seen in one place how the Daughter Nations have developed their art from that English School which is represented so splendidly in the Retrospective Galleries.

All the Dominions were invited to send the best of their own choice, and if it be questioned that the space given to the painters of the past is small compared with the whole of the varied collection, the answer is that, in a living Empire, the art best worthy of study is the work of living men.”

The guide apologised for the lack of sculpture from the countries of the Empire, but explained that this was due to the difficulties and risk of transporting sculpture over such long distance.

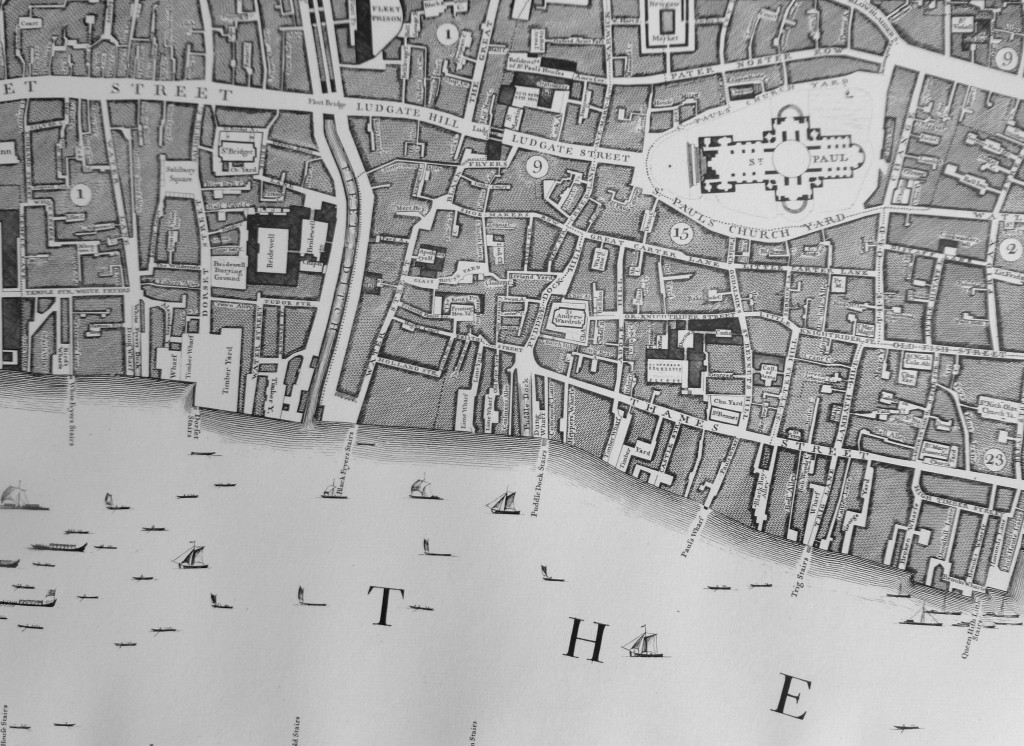

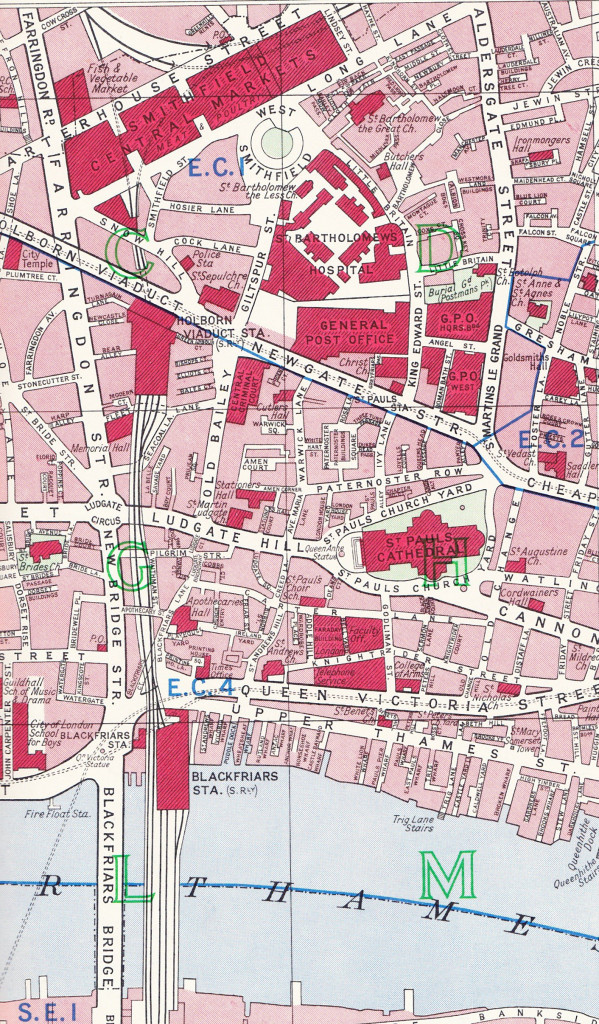

A rather strange part of the exhibition was a recreation of Old London Bridge, as shown in the following three photos:

The sign on the right of the photo, by the ramp is indicating that the station for trains to Marylebone can be found across the bridge.

I do not know what was used as the source for recreating London bridge, but it does not look like the majority of prints and drawing of the bridge.

Although the plan of the exhibition shown at the start of the post stated it was the British Empire Exhibition 1924, it actually ran over two years, and was open from the 23rd of April to the 1st of November 1924 and then from the 9th of May to the 31st of October 1925. The second year of opening was not originally planned, however the success of the exhibition led to the second year of opening.

The final closing ceremony on the last day of October 1925 was held in a very full stadium and was attended by the Duke of York (the future George VI) who gave the closing speech.

The ceremony suffered some very typical British weather as it was held in pouring rain, however the papers of the time reported that “In spite of the mist and the fog which enveloped the British Empire Exhibition today, thousands of people travelled to Wembley to attend the final scenes”.

The Duke of York closed the exhibition with the words “Further, the Exhibition, in its pavilions and by its spectacles in the Stadium has presented a picture of Empire which has kindled our imagination and stirred our pride in the Union Jack. In declaring the British Empire Exhibition closed, I am confident that its results will endure for the benefit of the British Empire and of its peaceful mission in the world.”

The British Empire Exhibition was considered a major success.

As well as the photos above, a number of films were made of the exhibition, a sample of which are below:

First, some remarkable colour film of London, building the site, the opening and the exhibition site (note that in the film it states that the closing ceremony was held 6 months later by the Prince of Wales. this was the closing ceremony for the first year, and a full ceremony was held as at the time it was not certain that the exhibition would open again in 1925. The decision to reopen would be taken in the following months):

A British Pathe film showing King George V and Queen Mary walking around the exhibition site:

The State Opening of the British Empire Exhibition, including a fly past by RAF byplanes:

Will It Be Ready In Time – film of the site during construction following concern about delays due to a strike by workers:

Film of one of the pageants held in the Empire / Wembley Stadium:

A variety of scenes from the exhibition:

I started the post with a comment that a look at the exhibition is interesting as it shows how much has changed in the space of one hundred years. Physical change at a place where London was expanding in the 1920s, change in Britain’s place in the world, and a change in attitudes, and I hope the above has shown how.

Wembley as a place is now so very different. A built up place, part of the wider London. The original Wembley Stadium, built for the 1924 exhibition was closed in 1999, demolished, and the stadium we see today opened in 2007.

The rest of the festival site is now full of apartment blocks, hotels, shops, and what is now the SSE Arena, was the Empire Pool Wembley, which was built over part of the artificial lake shown in some of the above photos, and completed in 1934.

Britain’s place in the world has changed dramatically. No longer an industrial and military power (of any size) and a lost empire.

And a change in attitudes from 1924, when you look at the paternalistic approach to the countries “under the British Flag” and the emphasis on resources, along with the sentence in the guide to the Palace of Art “how the Daughter Nations have developed their art from that English School“.

The 1924 exhibition did indicate some aspects of the future. it was the first major event which recognised the car as a significant means of personal transport, and it was the first time that the King’s voice had been heard via the radio, as the fledgling BBC had broadcast the opening ceremony.

The one thing that has not changed, as can be seen in the films, are the uniforms, carriages, and approach to Royalty.

The opening ceremony was probably one of the first big stadium opening events, and these continue, for example with the opening of the 2012 Olympics in Stratford.

I wonder how this will be looked at, one hundred years later in 2112.