Before heading to Christchurch Greyfriars, if you are interested in a walk exploring the history of Bankside, I have had one ticket returned from someone who cannot now attend the walk on Sunday 5th of June, and a couple of tickets are available for the walks later in July. The walk can be booked here.

I took the following photo in 1973, taken from Cheapside, looking towards the church of Christchurch Greyfriars using my very first camera, a simple Kodak Instamatic:

Not a very good photo, the Kodak Instamatic was a very simple camera. All the film was contained within a large cartridge, which included the exposed film. Pre-set focus and the only setting for exposure and speed were a single switch which could be moved either to sunny or cloudy. A very child friendly camera.

Roughly the same view, around 50 years later, in 2022:

Christchurch Greyfriars is an interesting, and distinctive church. A very different history to many other City churches.

It is distinctive, as whilst the tower of the church is intact, the body of the church is now a garden, with only one main side wall standing, and a short stub of the other sidewall. The rear wall is completely missing.

The church was destroyed during the night of the 29th December 1940, when much of the area surrounding, and to the north and south of St Paul’s Cathedral, was engulfed by the fires started by incendiary bombs. This was the raid that destroyed the area that would later be rebuilt as the Golden Lane and Barbican estates.

Christchurch Greyfriars was in one of my father’s photos taken from St Paul’s Cathedral just after the war, and can be seen in the following extract from one of the photos (the full series can be seen in this post, and this post):

As can be seen in the above photo, the church still retained its four walls. The church was destroyed by fire which burnt the contents of the church along with the roof, but left the walls standing.

In my 2022 photo you can count 5 windows in the remaining side wall. In the above photo, there are 6 windows (part of the 6th window on the right can just be seen to the left of the end wall of the church). There is also a two storey building which runs south from the end wall of the church.

The reason for these differences, and for the loss of the rear and southern side wall were changes in 1973 to allow the widening of King Edward Street, and the construction of a spur from Newgate Street into King Edward Street.

Christchurch Greyfriars was Grade I listed in 1950, however this protection appears to have been insufficient to prevent the demolition of much of the surviving walls.

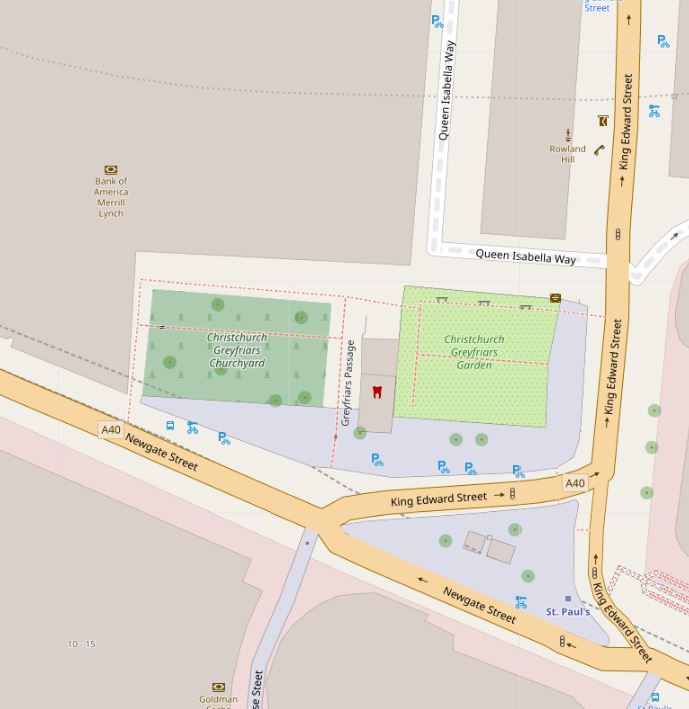

In the following map, Newgate Street runs from left to right, and the spur of King Edward Street can be seen cutting across where the two storey building was located. This, along with widening of King Edward Street, and the footpath along the street, resulted in the demolition of the end wall and shortening by one window of the north wall (© OpenStreetMap contributors).

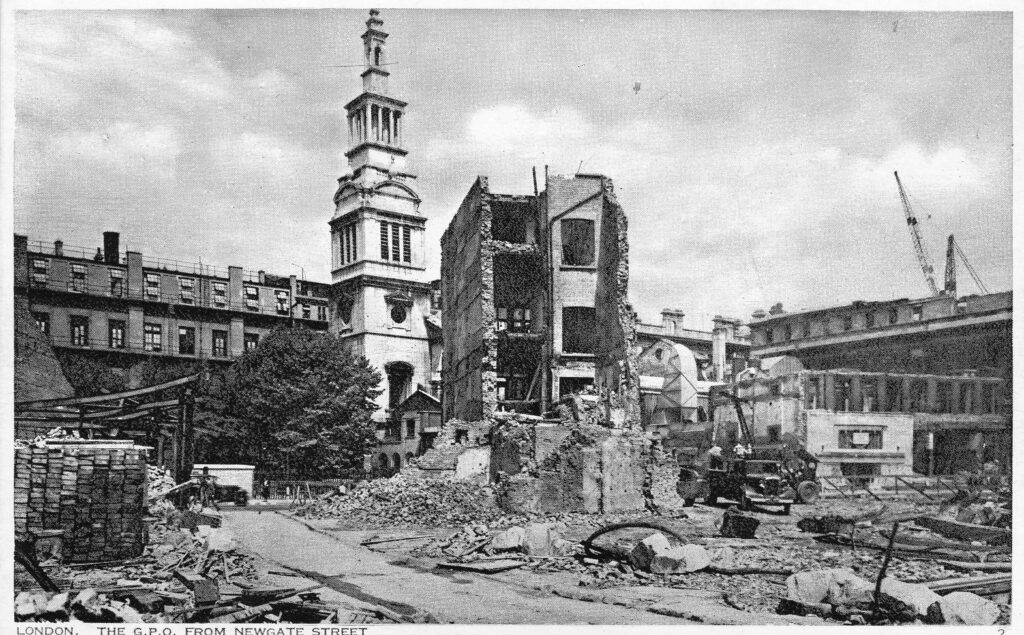

The church was included in the series of postcards “London under Fire”, issued during the war:

The church was also included in a couple of works by the artist Roland Vivian Pitchforth for the War Artists Advisory Committee. Both show the burnt out church with the surviving tower and walls:

And both show the two storey building to the south of the church where the slip road from Newgate Street to King Edward Street now runs:

Note that in the Imperial War Museum commentary for the above two prints, the focus in on the Post Office Buildings, one of which was the large building to the right of the church.

The Post Office, or British Telecom has had a long association with King Edward / Newgate Street, but has now moved away. In my 2022 photo there is a large building covered in white sheeting. This was the 1980s head office of British Telecom. It is now being converted into a mixed use development, and is unusual in the City in that the new building will retain the structural framework of the original rather than the usual full scale demolition and complete rebuild.

What has no doubt helped this approach is the height limitation around St Paul’s Cathedral so the usual high glass and steel tower was not an option.

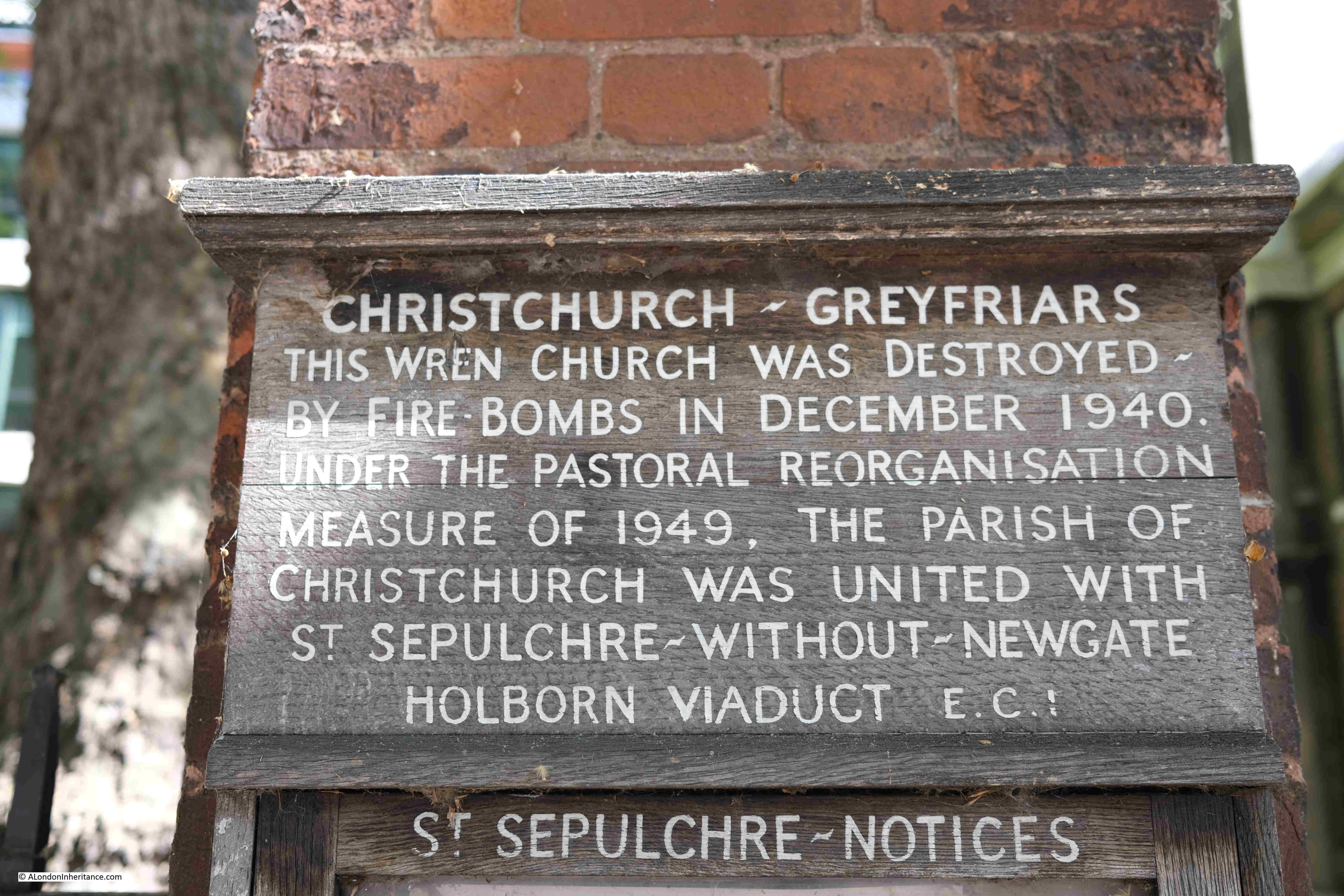

A sign close to the tower of the church confirms when and how Christchurch Greyfriars was destroyed (perhaps there should be a second plaque explaining how and why some of the walls disappeared).

The plaque also informs why there was no requirement to rebuild the church, as the old parish of the church was united with that of St Sepulchre-without-Newgate. The number of people living in the City had reached a point where there was an insufficient number of parishioners and regular church attendees to justify many of the old City churches.

A wooden font cover was rescued from the burning church on the 29th December 1940, and it can now be seen in the church of St Sepulchre.

To the west of the church is a small open space – the Christchurch Greyfriars churchyard:

This is not the traditional churchyard. William Morgan’s 1682 map of London provides a clue:

The church can be seen to the right of centre (although it is facing the wrong way), and to the left of the picture of the church, there is a rectangle labelled “Old Church”.

The original church was the church of a monastery established around 1228 on land to the north of the church by the Franciscan’s, or Greyfriars.

The first church on the site was built in the 13th century, demolished in 1306, and a new church built in 1325. This church was much larger than the church we see today, and as well as the space occupied by the current church ruins, also occupied the green space to the west of the church, hence the comment “Old Church” in the map extract.

The church attached to the monastery was of some size. According to “London Churches Before The Great Fire” (Wilberforce Jenkinson, 1917), the church was described as being “300 feet in length, in breadth 89 feet, and in height 64 feet”.

The book also states that “no other parish church contained the remains of so many of the great, there being there buried four queens, four duchesses, four countesses, one duke, two earls, eight barons, thirty-five knights, etc”.

The queens I can identify are:

- Queen Margaret, the second wife of King Edward I

- Queen Isabella, the wife of Edward II

- Queen Eleanor of Provence (just her heart so not sure if this really counts)

Cannot find who the fourth queen was, some sources reference Queen Joan of Scotland, however most sources state that she was buried in Perth.

Whether it was two and a bit queens, three or four, the church appears to have been a large and important church, as was the Franciscan monastery, with only St Paul’s Cathedral being greater in size.

The monastery was taken by the Crown during the Dissolution when Henry VIII took the properties of religious establishments across the country in the mid 16th century, and after a short period when the building was used for storage, the church became a local, although rather impressive, parish church.

“London Churches Before The Great Fire” records that Sir Martin Bowes, mayor of the City, sold all the ornate alabaster and marble monuments from the church for £50 in 1545.

Ornate memorials did continue after the church became a parish church, and the same book also records a memorial to Venetia, the wife of Sir Kenelm Digby who was buried in the church:

“Her husband tried to preserve her beauty by cosmetics and after her death had her bust of copper-gilt set up in the church. The bust was injured in the fire and was afterwards seen in a broker’s stall. She was painted by Vandyke.”

Bit of a lesson there on fame and beauty, that no matter how good looking, or famous, eventually we may all end up on the equivalent of a broker’s stall.

van Dyke’s portrait of Venetia, Lady Digby:

by Sir Anthony van Dyck

oil on canvas, circa 1633-1634

NPG 5727

© National Portrait Gallery, London. Creative Commons Reproduction

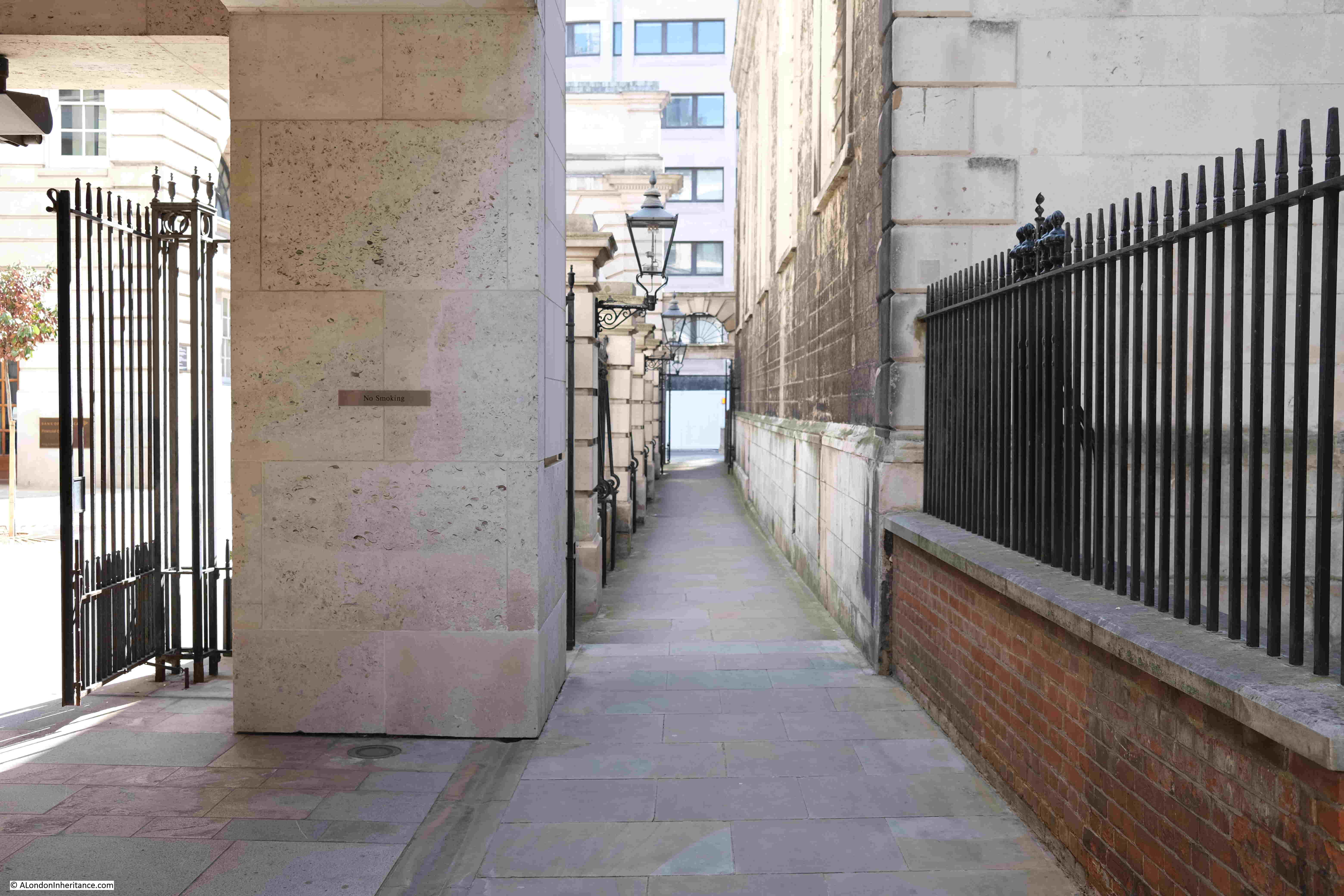

View down the alley between the remaining side wall to the north, and what were the old Post Office buildings:

The church was one of those lost during the Great Fire of London in 1666.

It was rebuilt by Wren between 1687 and 1704 on the foundations of the chancel of the original church. There was no need for a parish church to be the same size as the pre-fire church, and it was also expensive to rebuild with even the smaller church being one of Wren’s most expensive at a cost of over eleven thousand pounds.

It is remarkable just how many churches there were in the City of London. Today it seems as if you only need to walk a short distance to find another church but there were many more in previous centuries.

When Christchurch Greyfriars was rebuilt after the Great Fire, the church absorbed two smaller parishes, the parish of the wonderfully named St Nicholas in the Shambles, and that of St Ewin or Ewine. The churches for these two smaller, adjacent parishes were not rebuilt.

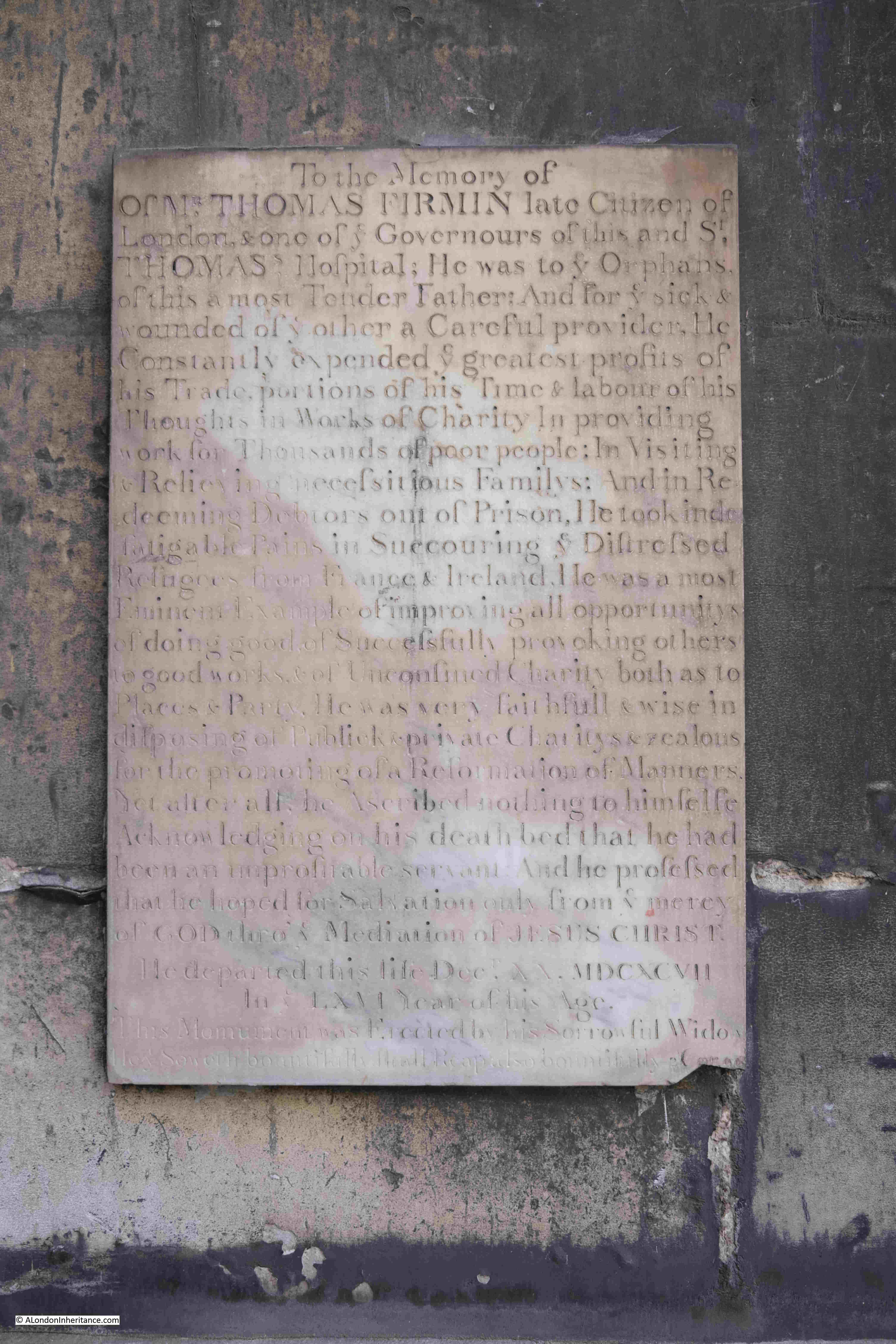

The base of the tower has a number of monuments which were rescued from the war damaged church:

After the church and the monastic buildings of the Franciscans were taken by the Crown, the buildings continued to have a close relationship.

There was always a need to provide help for London’s poor. There were many children throughout the city who did not have a father, or were part of a family that was struggling to feed them. In 1552 King Edward VI responded to this need by working with the mayor of the City to form a charitable organisation to provide for some of these children.

The result being that the old buildings of the Franciscans were taken over, donations were received, a Board of Governors set-up and in November 1552, Christ’s Hospital opened with an initial 380 pupils.

There is a sculpture on the southern side of the church of some of the children of Christ’s Hospital in their traditional school uniform:

Christchurch Greyfriars became the church for Christ’s Hospital.

The buildings of Christ’s Hospital were damaged during the Great Fire, rebuilt after, with a frontage designed by Wren.

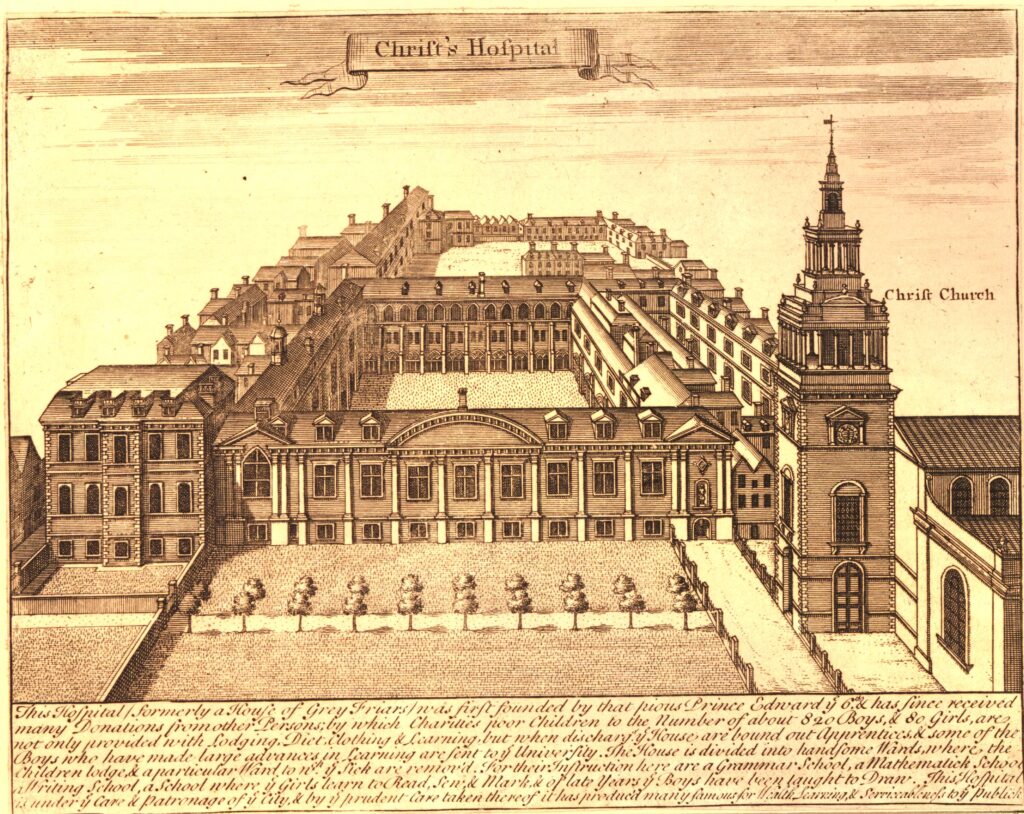

The following print from 1724 shows the church to the right, along with the impressive buildings of Christ’s Hospital (© The Trustees of the British Museum):

The text below the print provides some background on the school in the early 18th century:

“This Hospital, formerly a House of Grey Friars was first founded by that pious Prince Edward the 6th and has since received many donations from other persons by which Charities poor Children to the number of about 820 boys and 80 girls are not only provided with Lodging, Diet, Clothing and Learning, but when discharged of the House are bound out Apprentices and some of the Boys who have made large advances in Learning are sent to University. The House is divided into handsome Wards, where the Children lodge and a particular Ward where the sick are removed. For their instruction, here are a Grammar School, a Mathematick School a Writing School, a School where Girls learn to Read, Sew and Mark, and of late years, Boys have been taught to Draw. This Hospital is under the care and patronage of the City and by prudent care taken therefor it has produced many famous for Wealth, Learning and Servicableness to the public.”

Christ’s Hospital school left the site in 1902 and moved to Horsham in West Sussex where the school continues to this day.

View from next to the tower into the old body of the church:

View looking south towards St Paul’s where only one window and surrounding part of the southern wall remains:

What was the interior of the church was laid out as a rose garden in 1989, with a major update to the gardens in 2011. The configuration of this garden is intended to reflect the Wren church with the position of pews marked by the box edges and wooden towers where the old stone columns were located:

The northern wall of the church from what was the interior of the church:

If you return to my father’s photo of the church, you can see at the top corners of the church walls, there were stone pineapples. The ones rescued from the demolished walls can be found on the ground in the garden, next to the tower:

View along the centre of the church, pews would have been on either side with the small box hedges marking the edge of the pews:

A view of the tower of the church and part of the garden earlier in the year:

Christchurch Greyfriars is a survivor. Originally dating from the 13th century, it has survived being part of a Franciscan monastery, a charitable hospital / school, the Great Fire, the London Blitz and post war road construction and extension.

During many of these events, the church has shrunk in size, leaving the view we see today.

There was a campaign a number of years ago to rebuild the missing walls of the church, and for the church to become a memorial “to honour all Londoners who have been the victims of bombings in wartime and peacetime during the modern era”, however nothing seems to have come of this.

On a sunny spring or summer’s day, the gardens are a wonderful place to sit and contemplate the history of the church, surrounded by plants, flowers and bees.