Before exploring the London Telephone Box, an update on the walk exploring Islington’s place in the history of London’s water supply and some of the original buildings at New River Head, that I wrote about in a post a couple of week’s ago. I will be guiding on some of these walks and whilst most of walks have now sold out, the only walk that has tickets remaining is on Friday 10th September (PM). They can be booked here.

I cannot remember the last time I used a telephone box, or when I last saw anyone else using one. The mobile phone has effectively killed off the need to find a telephone box, yet they are still to be found across the city.

I have a number of photographic themes when walking London’s streets and for the last couple of years, London’s telephone boxes has been added to my theme list. So long a key part of the city’s street infrastructure, I wonder for how long they will survive.

The majority do not work, many have had their phone equipment removed, and many are not in a state that you would wish to stand in and make a call, even if they did work.

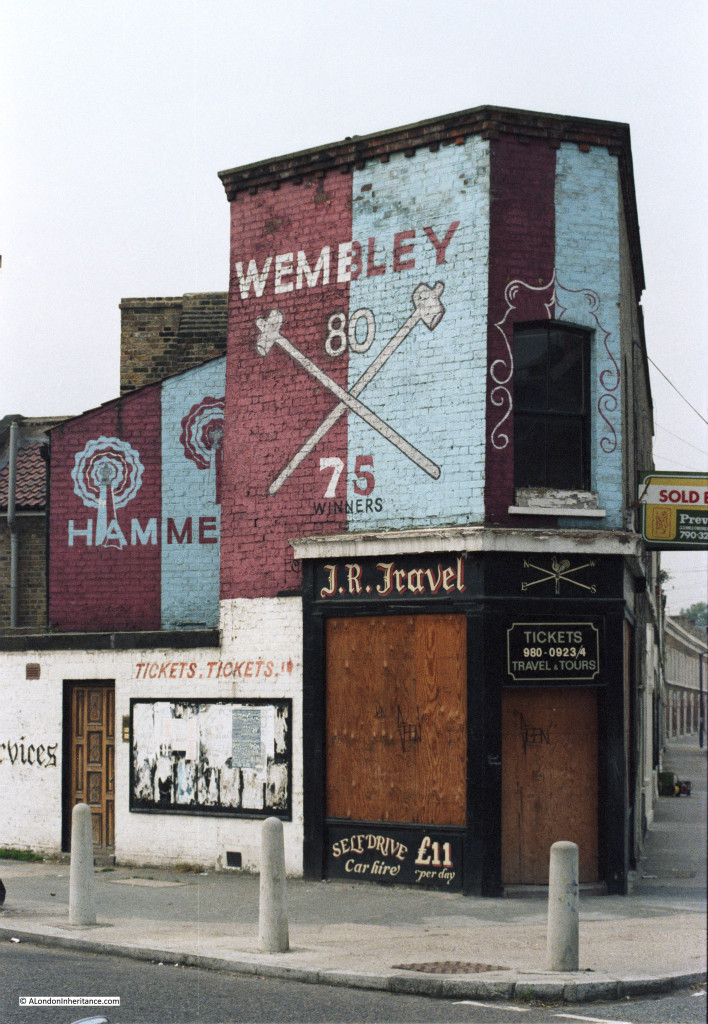

Some have found new uses. The most common being advertising as they are often in prime street locations, with full length advertising covering their windows.

The original red telephone box was designed by Sir Giles Gilbert Scott, a design he entered into a Post Office competition in 1924. The model K2 telephone box was the result, which first appeared on the streets of London in 1926. He would then update the design to the K6 which first appeared in 1934 and is the traditional red telephone box we see across the streets of the city.

There have been many modifications, and significant redesigns, the majority of these coming after the Post Office / British Telecom was privatised in the 1980s.

The technology in the phone box has changed over the years. I can just remember the manual method of paying for a call when you had to Press Button A to put coins into the phone to make a call, then if the call was not answered, Press Button B to return the coins.

Having the right change for a phone call was always a problem, and hearing the dreaded pips when the money was running out and you had no more change was a challenge for calls of more than a few minutes.

There are some 2,390 telephone boxes which have been listed by Historic England. The majority are Grade II, but some Grade II*. Historic England have a spreadsheet available for download here, which details the location of all listed telephone boxes.

I have to admit to finding telephone boxes rather scary. I know exactly why. As a young teenager I watched the short 1972 Spanish horror film La Cabina, or the telephone box on TV. It is why whenever I used a telephone box I would always keep my foot in the door, to keep it slightly open. The film is on Reddit, here.

So, still never letting a door shut me in a phone box, here are a selection of photos of London telephone boxes, starting with Charterhouse Square:

Grade II listed (the larger K6 models) telephone boxes at Smithfield Market:

One of the modern versions of the telephone box, also showing how so many of these are now used for advertising. This one is in Aldersgate Street:

Advertising is a potentially profitable business for the reuse of telephone boxes. They are in locations where they are easy to be seen, and where there is a high footfall, so they originally could be found when you wanted to make a call. These original reasons for locating a phone box also apply to sites where advertising works best, and as advertised on the phone box in the photo below, at the junction of London Wall and Moorgate, there is a company (Redphonebox Advertising) that specialises in this new use.

Perhaps the most photographed telephone box in London is this one in Great George Street / Parliament Square:

Before Covid, there would frequently be queues of tourists waiting to get their photo taken in a London red phone box with the Elizabeth Tower, or more probably Big Ben to those taking photos, in the background.

With the lack of tourists this phone box is now much quieter, and looking inside, even in such a prominent position, the telephone does not work, with the front panel being pulled away from the rear.

The following telephone boxes in Parliament Street are also a frequent destination for those wanting a photo with a phone box.

The following phone box is by the side of Grosvenor Road:

Internally, whilst the phone still has power, and the display reads BT Payphones, there is no chance of talking to anyone with the vandalised handset:

This view of the telephone box shows changing street furniture. The old, unused telephone box alongside a TfL cycle dock:

The above telephone box was made by Walter Macfarlane & Co, at their Saracen Foundry in Glasgow. It seems the company took on the manufacture of phone boxes in the late 1940s after their traditional markets started to disappear. The foundry closed, and the site demolished in 1967, however the company has left their mark on multiple telephone boxes across London:

Outside Pimlico Station:

Duncannon Street, looking towards Trafalgar Square and the National Gallery:

St Martins Lane, opposite the Duke of York’s theatre:

Great Newport Street:

The large blue plaque in the above photo records that the artist Joshua Reynolds lived there between 1753 and 1761.

Charing Cross Road, looking up towards the junction with Shaftsbury Avenue:

The telephone box in the following photo is in St Giles High Street with the church of St Giles in the Fields in the background. The door was left open, and at the time, it was not a phone box you would want to make a call from, even if it was working.

Shaftesbury Avenue:

Bloomsbury Street, opposite the Bloomsbury Street Hotel:

As with many telephone boxes across London, despite being in Bloomsbury Street, the phone box is used as a litter bin. The telephone equipment has been removed.

Outside the British Museum:

Telephone boxes have been converted to other uses. In Russell Square, two have been converted to a take away coffee shop:

Known as the Italian Tiramisu and Coffee Shop:

Walking further around Russell Square Gardens and there are another three, which according to the Historic England spreadsheet are Grade II listed:

At the entrance to Regent Square Gardens on Regent Square:

Looking inside the Regent Square Garden’s telephone box:

At the junction of Euston Road and North Gower Street:

Upper Street, Islington:

Across the road from the above phone box is the following:

Waterloo Place, looking up towards Piccadilly Circus:

The Strand, close to Charing Cross Station:

Opposite Charing Cross Station are these four telephone boxes:

They are usually more obvious, however the black hoardings to their right are slightly obscuring them.

Hard to imagine seeing a row of four, empty telephone boxes, however they were sited together in an area of frequent use. In a high footfall area, between the Strand, Charing Cross Station, Trafalgar Square and the theatres of the West End, they would have attracted a considerable number of users.

When I commuted into and out of London during the 1980s, train distruption would always lead to long queues at the phone boxes as the only means of communicating with those at home, or who you were to meet, that you would be late.

Later conversions of telephone boxes have tried to keep them relevant, however Internet access on a mobile phone renders WiFi from a phone box a failed model for their continued use.

These two telephone boxes are Grade II listed, so even if there are no customers who have an urgent need to make a telephone call from in front of St Paul’s Cathedral, they will probably be here long into the future:

In the triangle of land where St Martin’s le Grand meets Cheapside:

Telephone boxes advertising the time when cards as well as coins could be used to pay for a call:

Euston Road:

Outside St Pancras Station, with the sex work adverts that were once common across central London telephone boxes:

I titled this post the Death of the London Telephone Box, however that is not quite true. Many of them are listed so presumably will be around for years to come, and they are valuable assets as an advertising platform, however what they will not be used for is their original purpose of making telephone calls.

What is clear is that many are not maintained or cleaned. I have found very few that actually work. Many have had their equipment removed, others have been vandalised and many of the remainder are just dead.

I suspect the majority of people under the age of thirty have never used a telephone box, and find the concept of a fixed, wired phone rather antiquated.

They are a left over from a time when the only way to make a call when out on the streets was from a telephone box. When you needed to call for a lift home late at night, meet with friends, change an appointment, check on a place to meet, or just simply calling someone for a chat, the red telephone box was an essential part of street infrastructure.

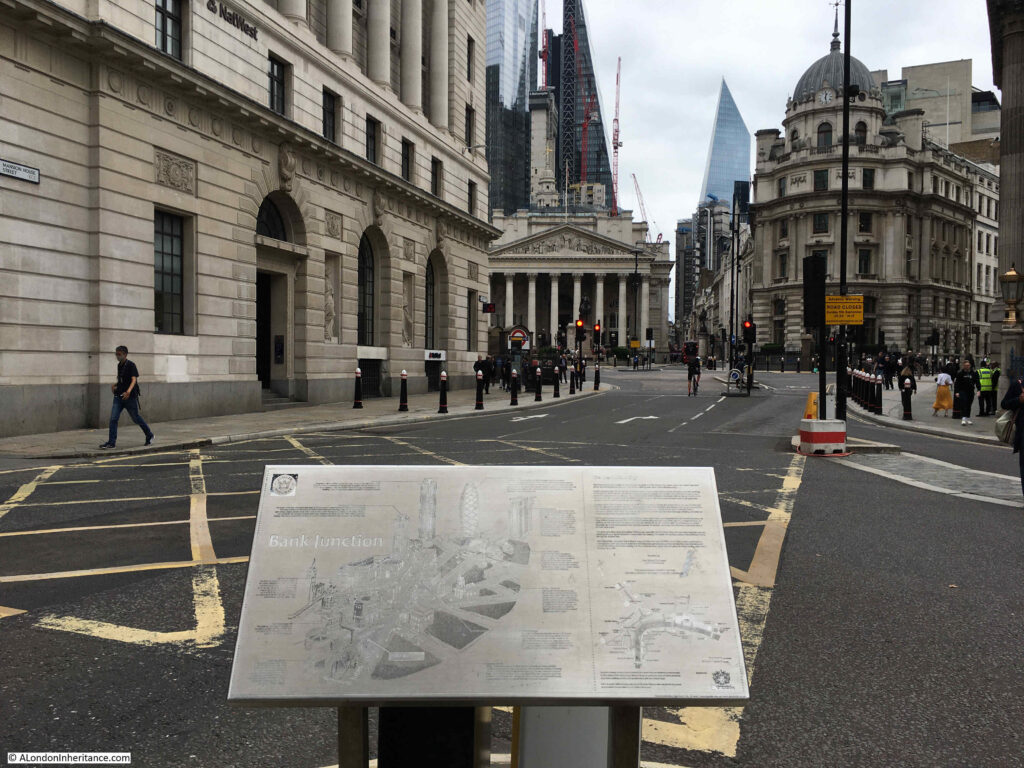

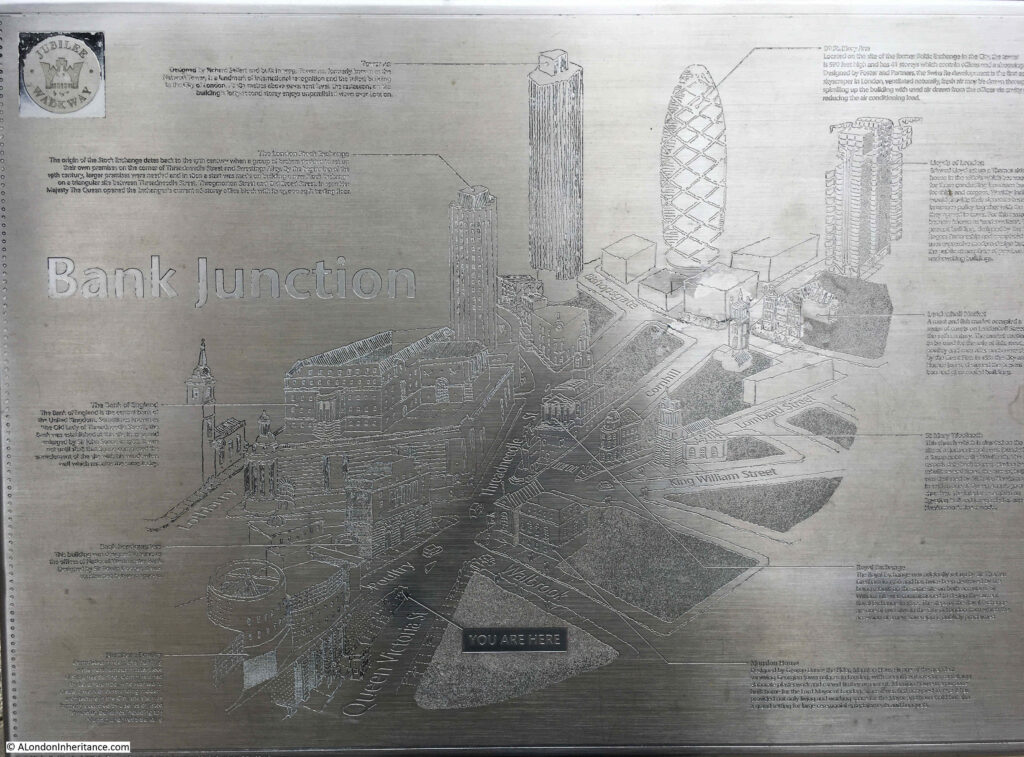

One of my other photographic themes is information panels, intended to show the passerby what can be seen in the area. I walked by this one a couple of weeks ago, close to the Bank junction:

The plaque was unveiled by the Queen in October 2002, and shows the City’s skyline as it was, just 19 years ago,

Thr highlighted buildings include the London Stock Exchange, Tower 42 (the old NatWest Tower), 30 St Mary Axe (the Gherkin) and the Lloyds of London building.

it is a strange location as none of these buildings can be seen from the location of the plaque. I cannot remember if it has been moved from a different location. The “You Are Here” label on the map implies it is in its original location.

Walking further into the Bank junction and only Tower 42 remains visible, although now partly obscured.

London’s streets will continuously change, as technologies change as do the buildings lining the streets.

As with the transition from telephone boxes to mobile phones, there seems to be another transition gradually underway with the introduction of low traffic neighbourhoods, closure of many city streets to vehicles, cycle lanes etc.

It will be interesting to see how this impacts the city’s recovery from the pandemic, Does it enhance the city, or restrict its viability as a place to work.

In future, will the car in a city be seen the same as a telephone box today, an essential in the past, irrelevant in the future?