To really understand London and the lives of Londoners, we need to look outside the city to see how London has influenced the development of so many other places, one prime example being Southend on Sea.

Southend on Sea is on the Thames Estuary, not quite the open sea, and very different to the river that passes through London.

The first settlement around Southend was to the north of the town at Prittlewell, probably dating from the 6th or 7th centuries.

There was gradual development over the centuries, but from the late 18th century development dramatically increased and Southend on Sea became a major seaside resort of the 19th and earlier 20th centuries.

Passenger ships from the heart of the City would ferry day visitors to Southend, and with the opening of two rail lines (Fenchurch Street to Southend Central in 1856 and Liverpool Street to Southend Victoria in 1889), large numbers of Londoners would make their way to experience a day on the coast and to walk along the pier.

Southend is only Southend because of London.

As this is a Bank Holiday weekend, it seemed appropriate to join the thousands of Londoners who have made the same journey over the years and take a trip out to Southend on Sea.

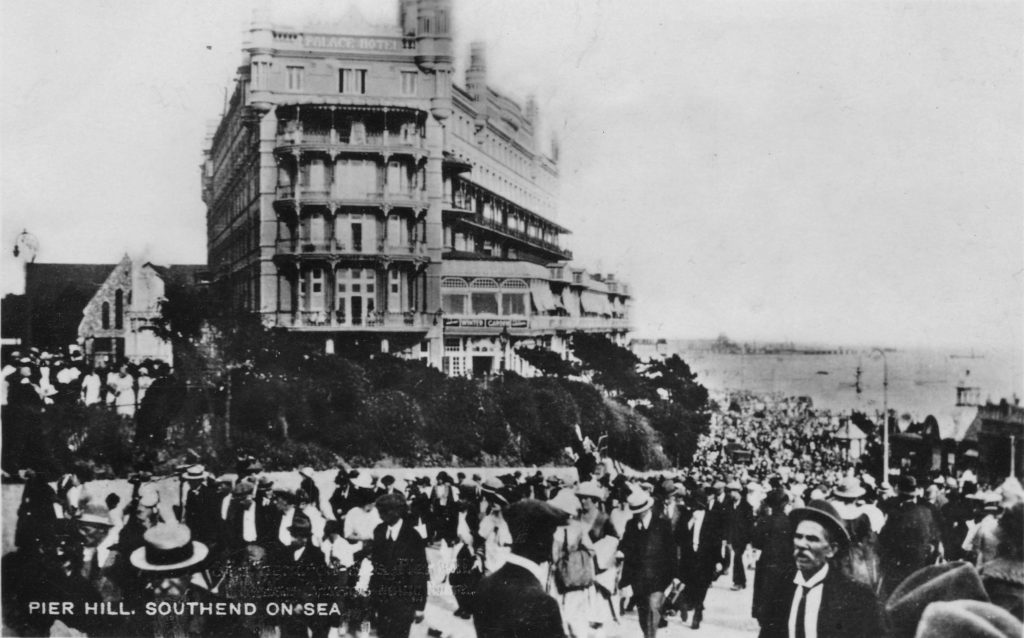

The above photo shows crowds streaming up Pier Hill. This leads from the pier and the parade along the sea front, up to the high street and the stations. It was probably taken towards the end of the day when day trippers were heading back to the stations for their journey back into London.

The Southend Standard from August 1910 provides a wonderful description of Southend on an August Bank Holiday:

“HOW SOUTHEND SPENT BANK HOLIDAY – Last year Bank Holiday was cold and wet, and holiday makers had a good deal of their enjoyment marred by cold winds and frequent showers. This year however, the Clerk of Weather changed his mind for once, and was in his most genial mood.

The sun shone from early morn to dewy eve; his somewhat warm attentions being tempered by a cool and steady breeze. Very early in the morning the incoming excursion trains began to unload their human cargoes; the railway stations, like gigantic hearts, beat at regular intervals and sent the human tides flowing outwards, to disperse themselves along the various arteries and veins of the town.

Such crowds there were too; everyone in their holiday rig; artisans and their wives, the poorer class of clerks, ‘Arry in fearsome ties, the latest cut of trousers, and bowler or straw hat stuck jauntily on one side; ‘Arriet in all the glory of purple velveteen, brown boots and large hat with sweeping ostrich feather; everybody and his uncle as the saying goes, was in the crowd that ceaselessly passed down the high street and spread itself along the front. By midday, the Parade was a sight worth seeing; right away from Westcliffe to Luna Park, the great mass of holiday making humanity moved to and fro and back again, like the tides of the estuary, merry laughter, jokes and greetings were everywhere. But it was down along the east front, in the afternoon that the holiday crowd was seen at its best, there the genus tripper was present in every variety.

The stalls which purveyed fearsome and wonderfully made American drinks did a roaring trade. Every fruit shop was the centre of a knot of customers and even the establishment whose claim to attention lay in the handing out of frizzling hot sausages and steaming mashed potatoes did a brisk trade.

From the shops at the commencement of the Parade to the gasworks every place did a roaring trade, they might have been huge magnets and the coins in the pockets of those outside made of steel, so quickly did the later pass over the counters, and from hand to hand.

The spaces of beach and sand which were left vacant were filled with hundreds of children and grown-ups, who sat about and enjoyed themselves to the full. In the pools left by the residing tide the youngsters had great sport, and with pail and spade and tucked-up clothes, splashed and dug to their hearts contents.

‘Arries and ‘Arriets, regardless of the dust and the heat, danced round piano organs in the East End style, which is only born and cannot be taught.

By six o’clock in the evening the human tides begin to return to the railway stations and crowd the trains again. Much singing and dancing was there, not quite so clear and steady as in the morning, but nevertheless all good humoured.”

The train companies would arrange special excursion trains from London to Southend for Bank Holiday weekends, and newspapers in advance of the weekend would carry advertisements detailing the times and prices for those wanting to leave the city for a day by the sea. Very different to today, where the Bank Holiday is often a time for closures and engineering works, rather than special trains heading to the coast.

Southend Pier has long been a central feature of a day by the sea. The original pier opened in 1830, and the iron pier that we can walk along today followed in 1889. The end of the pier was extended several times with the Prince George Extension opened in 1929 bringing the length of the pier to 1.34 miles.

The pier railway was opened in 1890, reaching the end of the pier in 1891.

In the following years, Southend Pier has been hit by ships and suffered a number of fires. At times it seemed that the pier would not be restored and might even be closed, but somehow it has continued to stay open, a train still runs the length of the pier, and the buildings at the pier-head have been restored.

Time for a Bank Holiday walk along the pier:

Once you start walking along the pier, the beauty of the estuary sky becomes apparent. The land on either side of the estuary almost blends with the water, and the wide open sky stretches from horizon to horizon.

Distance markers tell you how far along the pier you have walked – and how far you still have to go.

The Southend Pier Railway still runs the length of the pier.

The first 1830 version of the pier included a horse-drawn tramway, however this was replaced by an electric tramway in 1890 soon after completion of the iron pier.

There have been a number of different versions of the pier train over the years – this is the first version I remember, with the bowling alley in the background which once was the main building over the start of the pier.

Conditions on a warm August day are very different to the wind and rain the pier has to endure, sticking over a mile out into a flat estuary with no protection from everything that the weather can throw at the pier.

The pier therefore needs constant maintenance. Replacement of the wooden boards lining the walkway, painting of the railings, replacement and restoration of the iron supports of the pier.

Looking back along the pier from alongside the station at the pier-head.

End of the pier station and estuary sky.

Colour at the end of the pier.

The pier did comprise upper and lower decks at the pier-head. The lower decks are now closed off.

Pier head:

Looking back at the pier head:

The following photo from the Britain from Above archive is titled “The Royal Eagle Paddle Steamer alongside Southend Pier, Southend-on-Sea, from the south-east, 1939”

Note the two decks along the pier head, and the crowds of people on the pier and the ship.

The Royal Eagle ran regular day trips from the centre of London out to Southend, Margate and Ramsgate.

A typical advert for the service from May 1933 read:

“London’s Luxury Liners – Commencing 3rd June Daily (Fridays excepted) Royal Eagle for Southend, Margate & Ramsgate from Tower Pier at 9.20 a.m. Greenwich 9.50, North Woolwich 10.20.”

Day return fares during the week to Southend were 4 shillings and 5 shillings on Saturdays, Sundays and Bank Holidays.

If you wanted a slightly longer day at Southend, the Crested Eagle left Tower Pier at 9 a.m.

The mid section of the pier head as it was pre-war. Note also the end of the pier station, with two covered platforms for trains.

The very end of the pier:

The view back along the pier towards Southend from the end of the pier:

From our 2019 viewpoint, it is probably hard to understand just how much a day out at Southend meant to someone living in East London. The ability to escape from the daily pressures of trying to earn enough to feed and house your family must have been essential to make life worth living. Whilst researching through newspapers, I came across the following tragic example from 1921. Hopefully a very rare case, but it does highlight what a day out at Southend meant to an east Londoner:

“TRAGEDY OF BOY’S SUIT IN PAWN – LOSS OF HOLIDAY CAUSES MOTHER’S SUICIDE.

Worried because she could not raise the money necessary to get her boy’s Sunday suit out of pawn so that he could go to Southend on Bank Holiday, Ellen Woolf (44) of Mile End, committed suicide by swallowing carbolic acid.

It was said at the inquest that the woman had had 14 children, of whom eight were living, and the clothes had been pawned during the week in order to get food.

She had also had additional worries over a sick child and debt. The husband served in France during the war, and was badly wounded. Before and since, for over 20 years, he had sold newspapers in Leadenhall-street for a living.

Suicide while of unsound mind was the verdict.”

The verdict should really have drawn attention to the pressures she must have been under, as these must have been the root cause of her state of mind – I will never take a trip to Southend for granted again.

Southend has had to change and adapt to continue to attract visitors who want more that just a walk along the pier or the Parade. As the 1910 report stated, in 2019 it is still about money, and attracting the coin out of the visitors pocket.

On either side of the pier, along the sea front is Adventure Island – a dense cluster of rides and amusements.

The following photo from the Britain from Above archive shows the sunken gardens in 1928, this is the same space as shown in the above photo.

The old Marine Parade, or Golden Mile runs along the sea front to the east of the pier.

This was one of the places to go in the late 1970s with my first car on a Saturday night. Clubs such as Talk of the South (ToTS) were in the buildings on the left and customised cars would spend their time driving up and down the Golden Mile. Southend on a Saturday night was exciting when you are 17.

It was a very different scene in the early years of the 20th century:

Large amusement arcades now line the street:

There have been proposals over the years to demolish and rebuild large parts of the Golden Mile, but they never seem to move beyond the conceptual stage, so Southend’s brightly coloured and gloriously tacky eastern seafront continues into the 21st century.

At the end of the street is the Kursal, now a shadow of its former self.

Opened in 1894 with the main entrance buildings opening in 1901, the Kursal consisted of dining halls, billiard rooms, bars etc. in the main building, with a large fairground covering the land behind.

The Kursal has been through many changes in use and ownership. In 1910 it was renamed the Luna Park, as referenced in the newspaper article at the start of the post. It has been used for greyhound racing and in the 1970s, the main ballroom was a rather good live music venue.

Leaving the seafront and walking up Pier Hill we find this strategically placed souvenir shop:

The shop has been here for as long as I can remember, and it is on the route back to the High Street and train stations from the pier and sea front. Just the place to stop off and buy your last minute souvenir before returning on the train to London.

Southend is not all garish seaside buildings, there is some wonderful historic architecture. At the top of Pier Hill, turning to the west along the cliff top is the Royal Terrace.

At the far end, on the corner with the High Street, is the Royal Hotel and a line of late 18th century houses run along the street with superb views over the pier and estuary.

The terrace was built between 1791 and 1793. The “Royal” name of the terrace was given after the 1803 visit of Princess Caroline (the wife of the Prince Regent), who occupied numbers 7,8 and 9 – the houses in the centre of the photo below.

At the end of the Royal Terrace is the Cliff Lift, providing pedestrians with a route between the sea front and the top of the cliff if they want to avoid the walk.

In 1901, a moving walkway was installed on the site, replaced by the lift which was constructed in 1912.

The lift has undergone several refurbishments and updates since, the most recent being a £3 million upgrade in 2010.

For 50p you can be carried smoothly up to the Royal Terrace:

One final view across the estuary, where sand blends into mud, then water then sky, with a thin sliver of land across in Kent. Hard to believe that this is the the river that flows through central London, now over 4 miles wide between Southend and the Kent coasts.

Southend is only the Southend we see today because of London. A long heritage of being one of the main destinations for Summer weekends and Bank Holidays for those who lived in London.

Easy transport provided by passenger ships on the river and the opening of two railway lines to central London helped bring crowds out of London to spend their money in Southend. In the late 1920s and 1930 a new main road (now the A127) was opened between the Eastern Avenue at Romford and Southend, adding a dual carriageway from east London directly to Southend as visitors started the move from ship and train to car – a trend that would be accelerated in the post war years.

Tastes will continue to change and what people want from a day at the seaside will evolve, but I suspect that Southend will respond as it has done for two hundred years, and develop new ways to, as the 1910 article stated, remove the coin from the pocket of the visitor, but for me it will always be a place to get lost in the wonderful estuary sky.