I am fascinated by both London, and the impact that London has had on the wider country. Even some of the most remote parts of the surrounding counties have felt the threat of London’s continual growth, and the infrastructure needed to service the rapacious city. To find such a place, and to walk what has been called the country’s most dangerous footpath, took me to Wakering Stairs in Essex last Sunday morning at 7am, ready to walk the Broomway.

The Broomway is an ancient footpath, several hundred years old, that links mainland Essex at Great Wakering with Foulness Island.

Foulness is now mainly Ministry of Defence property, although it does have a small community living on the island. The MoD have built a bridge connecting with the mainland, however before the bridge was constructed, the only way for residents to get to and from the island was via a boat across one of the creeks and channels that surrounded the island, or via the Broomway.

The shore facing the wider Thames Estuary / extreme southern part of the North Sea is extremely flat and extends a considerable distance from land. This has resulted in a large area of flat sands that are either covered by water, or as exposed sand, mud and low lying water, depending on the tide.

The part of the shore close to land is comprised of a black organic mud, that is very sticky, can drag down someone who walks into this area, and is very difficult to get out of.

Further out, there are reasonably stable sands, however these still have their dangers. It is these sands that offer a route to travel between the mainland and Foulness when the tide allowed, and was marked by poles of Broom and was used for centuries as a route to and from Foulness.

I have long wanted to walk the Broomway. I am reasonably good at planning routes which involve the tide, walking over tidal mudflats etc. however the Broomway is not a route I would take without an expert guide.

Tom Bennett is qualified in a number of outdoor activities, and offers guided walks along the Broomway. These sell out quickly, but a number of months ago I was able to book a walk in October, not my preferred month due to the risks of autumn weather, but in the end, it turned out to be a perfect day’s walking.

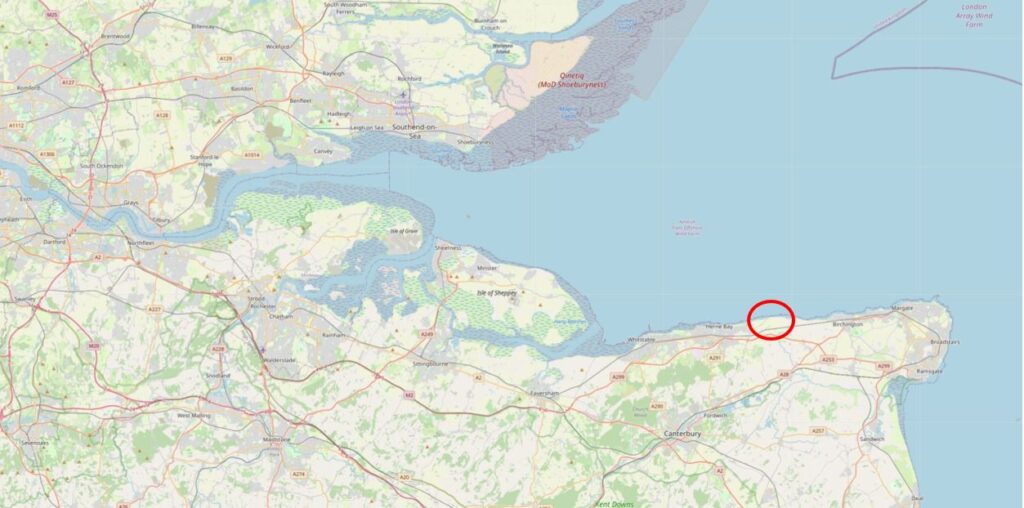

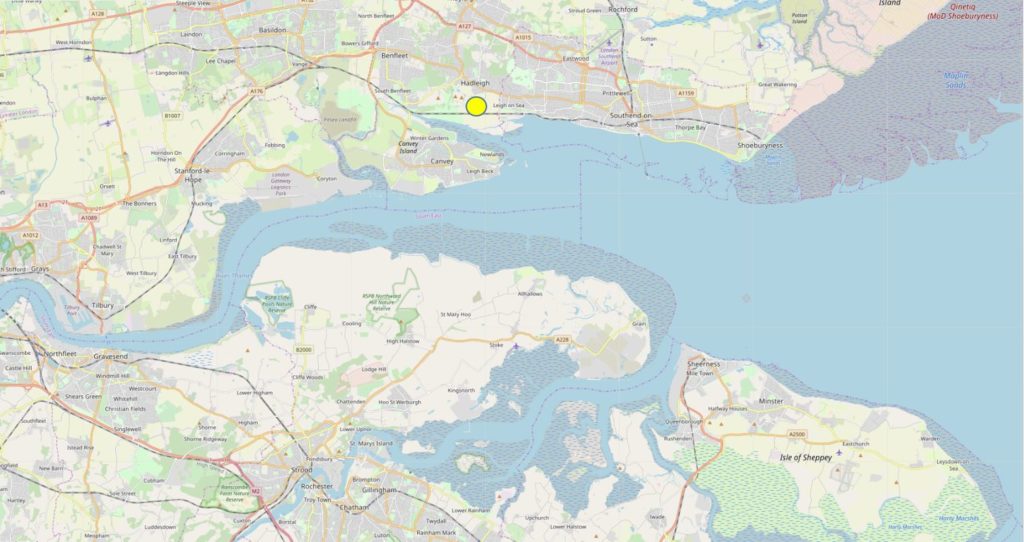

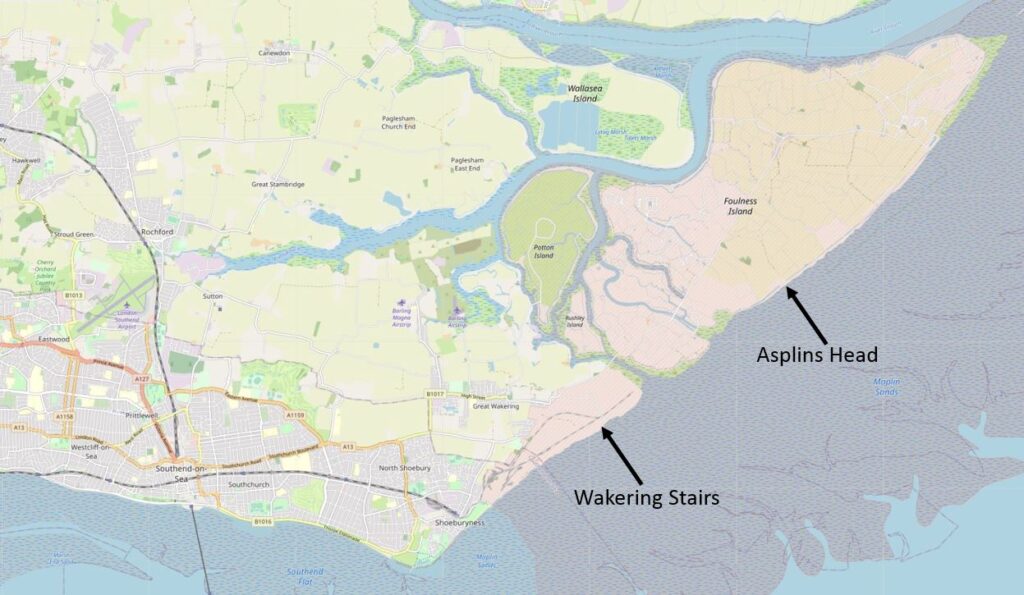

The route taken was between Wakering Stairs and Asplins Head, and the following map shows the location of these points, along with the location of Foulness, to the north-east of Southend (© OpenStreetMap contributors).

This is not the full route of the Broomway which originally went all the way along the easterly coast of Foulness, and there were a number of access points between the Broomway and the land.

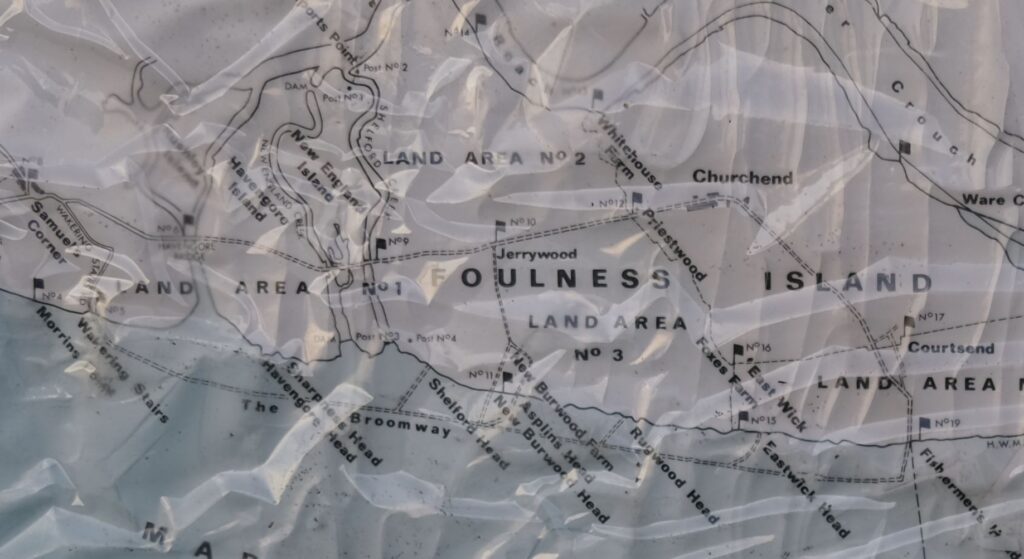

I photographed the map on an information panel at Wakering Stairs, where there are plenty of warnings about the dangers of the area. The map shows the Broomway running parallel, but a distance offshore, to Foulness, and also shows the full length of the path, and the points where it is relatively safe to travel through the dangerous areas of mud near land and reach Foulness.

The time needed to walk the whole footpath, and return along the same route is such that it is difficult to avoid the incoming tide, so the walk last Sunday covered half the route.

Standing at Wakering Stairs at seven in the morning, looking out over the mudflats is rather magical. The sun rising above the distant sea, the sounds of flocks of birds on, and flying above the mud flats:

In the above photo, on the right, where the sea meets the sky, the Redsands Maunsell Fort can be seen.

So what is the London connection?

Maplin Sands is the name of the large area of sands offshore Foulness, and in the early 1970s, it was Maplin Sands and Foulness that almost became London’s third airport.

In the 1960s, London had two main airports, Heathrow and Gatwick. Air travel was growing rapidly, and this growth was expected to continue well into the future, so the search began for the site of a new airport.

In 1968 the Roskill Commission, also known as the Commission on the Third London Airport was formed, with the aim of investigating options, and making a recommendation for the location of the new airport. The commission was named after High Court Judge Eustace Roskill.

The locations were narrowed down to four, Cubington in Buckinghamshire, Foulness in Essex, Nuthampstead in Hertfordshire and Thurleigh in Bedfordshire.

The commission published their report in 1971, with a recommendation that Cubington in Buckinghamshire should be the site of the third London airport. The commission turned down the Foulness option mainly due to issues with accessibility, as Foulness was on an isolated part of the Essex coast, with no current, or easy to implement transport options. The commission feared that if transport options could be put in place, they would still be too far from central London, and airlines would continue to prefer Heathrow and Gatwick.

The Government turned down this recommendation, and went for Foulness which had been put forward in a separate report by Professor Colin Buchanan, a dissenting member of the Roskill Commission.

The reasons for this decision were the avoidance of significant impact to countryside and people, there was pressure from well funded groups opposing Cubington. Essex County Council were in favour of Foulness, and it was seen as a way to regenerate the area around Southend.

In the 1972-73 Parliamentary Session, the Maplin Development Bill was introduced and the Maplin Development Authority was set-up, which would have the responsibility for the development of the land, which, as well as the airport, would include a deep water port and new town, along with the transport links needed to connect the new airport to London, and the rest of the country.

The airport was supported by the then Conservative Prime Minister, Edward Heath, however it would not last long, with only minimal works to test whether the Maplin Sands could be reclaimed for the construction of the airport.

In March 1974 the Labour Party took over in Government, and commenced a review into the airport. In july 1974 the review was published and Peter Shore, the Labour MP for Stepney and Poplar announced that the Foulness / Maplin Airport project would be abandoned.

Back to the Broomway, and the walk over what could have become the third London airport, started at 7:30 am. The walk left Wakering Stairs and headed out, away from the coastline, and the dangerous mud. The following view is out on the Broomway, looking back towards Wakering Stairs:

The above photo shows large expanse of sands and water with hardly any landmarks. The first we reached was a small patch of grass growing in isolation:

To the south, Foulness is separated from the mainland by the Havengore Creek. Today, there is a bridge over the creek which is part of the upgraded roads along Foulness used by the limited number of occupants, and primarily by the Ministry of Defence (MoD).

In the following photo the Havengore Bridge can be seen in the distance as we walk over the sands where the creek flows into the sea.

The island’s connection with the MoD starts in the mid 19th century when the War Office used sands to the south as an artillery range. The War Office tried to expand to the north and attempted to purchase Foulness Island from the Lord of the Manor, however he refused, although the War Office started to buy up any land or farms that became available.

When Alan Finch, the Lord of the Manor died in 1914, his half-brother inherited the estate and agreed to sell to the War Office, who then owned over two thirds of the island.

Since 1915, Foulness has effectively been a closed island. Mainly used by the MoD for weapons testing, but with a small community remaining and some farming.

The Essex Weekly News on the 18th of December 1914, described the island as:

“AN OLD WORLD PLACE – If Foulness island becomes simply a military area we shall see there after two thousand years an instance of how history repeats itself. The Romans selected Mersey Island further along the Essex shore as a military camp, and fortified it against invasions by Norsemen. Now another foe, equally barbarous again threatens us from the North Sea.

Foulness is very flat and scantily wooded, and but few farm houses and cottages are in view, although there is a population of about 480. The island was constituted a parish in 1550. The Parish Church erected in 1850 on the site of a series of wooden buildings, is dedicated to St Mary.

The nearest point on the mainland to Foulness is Great Wakering from whence as a spot known as “The Stairs” it is reached at low tide by a headway over the sands. Stubby tufts of broom stuck in the sand about thirty yards apart mark the way for the traveler. There have been some narrow escapes by those who have ventured along this wave-washed road; and indeed few experiences are more alarming than to find one-self along the ‘Broom-way’ as the road is called, a couple of miles from land in the dusk of a winter’s day with the tide beginning to race across the Maplins.”

Once out on the Broomway, it is easy to appreciate the risks whilst walking along this “wave-washed road”. You are separated from land by a dangerous area of mud. There are no visual reference points. The land is so flat that when the tide comes in, it does so rapidly. Not an incoming visible wave of water, rather a deceptive rise in the water level all around that cuts you off from the land.

The following view is looking out to sea from the Broomway. The sea is not visible, just an endless scene of sand and water until the horizon meets the sky:

And in the following photo, looking back to land from the Broomway, which is now a narrow strip on the horizon, with the “Black Grounds” of dangerous mud separating you from the safety of the land.

The military use of Foulness caused additional risk to those navigating the Broomway. The area was used for training and the test firing of guns and ammunition. This use continues to this day, and there are large warning signs at Wakering Stairs advising that “Do not approach any object or debris as it may explode and cause serious injury or kill”.

Newspaper reports illustrate the risk when the Broomway was in use by Foulness residents, as the following from the Southend Standard and Essex Weekly Advertiser on the 1st of December 1910 reports:

“FACING DEATH AT FOULNESS – EXCITING INCIDENT ON THE BROOMWAY: For a long time there have been many loud complaints from the people whose vocation causes them to use the road known as the Broomway from Wakering Stairs to Foulness Island, as to the serious danger which is caused by the gun practice from the Garrison at Shoeburyness.

On Tuesday last two people were driving across the Broomway when they had the narrowest of escapes from death, or serious disablement, by the bursting of a shell. They were in two traps, a few yards behind each other, and their attention was drawn to the gun firing which was going on from the Garrison. Naturally enough they felt no fear of danger, as the Broomway is on the edge of space allowed for practice is a mile or more away.

Several shots passed a safe distance away, but suddenly one great shell ploughed into the mud not more than thirty yards away and burst with a loud explosion. Vast quantities of mud and water were thrown out in all directions, and some of it, in great lumps, struck the two gentlemen who were driving, So great was the force of the explosion that a hole many feet long and deep, big enough to hold a wagon and team, was dug out. The horses were scared, and it was only with considerable difficulty that they could be prevented from bolting.”

The Broomway is only accessible from Wakering Stairs at the weekend as during the week, Foulness is still used for live firing.

Continuing the walk along the Broomway, and the most significant landmark on the sands comes into view. This is the Havengore Maypole:

It is known as the Havengore Maypole as it marks a channel into Havengore Creek much further to the coast, and was once held in place by cables extending from the top of the pole to moorings in the sands, one of which can be seen to the left of the pole on the following photo:

The Havengore Maypole is a significant marker in the wide expanse of featureless sand and water, however it was surprising how difficult it was to see from any distance. This is a problem with navigating the Broomway in that everything seems to blend into a featureless landscape, including the distant sea and land.

The weather on the day of my walk was really good. Clear skies, light wind and good visibility, however the Broomway is also at risk from sea fogs and mists which can roll in rapidly leaving a walker lost in a grey fog with no idea of the direction of travel.

There are stories of people being lost in fogs and walking out to sea rather than towards land.

The name Broomway comes from the use of sticks of Broom placed in the sands at regular intervals. By following these sticks, the traveler had confidence that they were on a safe route. They only then had the tide, fogs and the risk of an exploding shell to worry about.

There are very few of these markers left today, just the occasional base of a pole sticking out of the sands:

For centuries the Broomway was the main route between Foulness and the mainland. There is written evidence of its existence back to the 16th century, and it is probably much older.

It was used by all manner of means of transport. Coaches, pony and traps, bikes, walkers. Newspaper reports of travel along the Broomway mention that the Postman had one of the most dangerous jobs as he had to travel the Broomway on an almost daily basis.

Even at low tide the sands are covered by pools of water and there are a number of larger channels of water to cross:

Maplin Sands – Nothing but sand, water and sky, and somewhere in the distance is the sea with the returning tide:

After 5km of walking across the sands, we reached Asplins Head, the point where there is a causeway across the dangerous muds providing a safe route onto Foulness. The following photo shows the end of the causeway furthest from the land. It is a jumble of rocks and broken concrete.

If you look to the left half of the photo, where the sands meet the sky, you can make out a low wall. Apparently this enclosed an area that was used to test how fuel burnt with fuel being pumped into the space bounded by the wall and set on fire.

The view towards Foulness showing the length of the causeway:

The view from Foulness along the Asplins Head causeway. The low wall of the circular enclosure for fuel testing can be seen on the sands to the left:

Whilst the Broomway continues further than Asplins Head, continuing on the route at a reasonable walking pace, and being able to return to Wakering Stairs is a risk with the returning tide, so Asplins Head is as far as the walk took us along the Broomway.

After a short break, it was then a final 5km walk back along the Broomway to Wakering Stairs.

The Broomway is a fascinating walk. Despite the proximity of the MoD, and the use of the sands for weapons testing, Maplin Sands still feels very natural. Large flocks of wadding birds are further out on the sands, and the casts of lugworms are frequently seen on the sands.

The area had a lucky escape in the 1970s when plans to build the third London Airport on Foulness and Maplin Sands were cancelled.

The remote areas of the Thames Estuary have been the focus for a number of airport proposals over the decades. See my post on the Crow Stone, London Stone and an Estuary Airport for an example of the most recent proposals for an airport on the Isle of Grain and the Hoo Peninsula in north Kent.

Researching the history of the airport proposals, and at the time there was much support for an airport at Foulness, both within the local area, and from around London.

Two examples show very different reasons for supporting the proposals.

Toby Jessel, the MP for Twickenham was a vocal supporter of the Foulness airport. He had long been raising issues with the increasing number of flights at Heathrow, the disruption that noise caused to residents, and even the risk of an aircraft crash in heavily populated areas of London as the number of flights increased. He also saw Foulness as the option that would result in less damage to the countryside compared to the inland options.

There was also an article in the Stage and Television Today on the 19th of October 1972, which I found amusing as it relates to the opening of a club / disco in Southend that I frequented in the late 1970s – Talk of the South (better known as TOTS), and that its opening was down to the possibility of Foulness Airport:

“Southend, and more generally speaking the South of England, have been left out on a limb as it were as far as good cabaret facilities are concerned and it is fair to say that it was not without consideration of the new Foulness Airport, Britain’s new number one air terminal, that the idea of a delux cabaret club was formed.”

TOTS closed a couple of years ago, but it lasted for much longer than the airport proposals.

The Broomway is not a walk to take without the experience and skill needed to plan and navigate a path a long distance from shore, covering dangerous sands, and at risk of a rapidly incoming tide and changing weather conditions.

I booked my walk via Tom Bennett Outdoors, and his walks can be booked here.