A couple of weeks ago, I finally managed to get to a place I have been wanting to visit for years. It took a bit of planning, but took me to a location that still has evidence of the City of London’s original jurisdiction over the River Thames.

To the west of Southend, on the borders with Leigh, and by Yantlet Creek on the Isle of Grain, there is a line across the River Thames which marked the limits of the City of London’s power. Where this line touched the shore, stone obelisks were set up to act as a physical marker.

These stone markers are still to be found, so I set out to visit both stones, and to explore the history of the City of London’s jurisdiction over the river, up to the estuary.

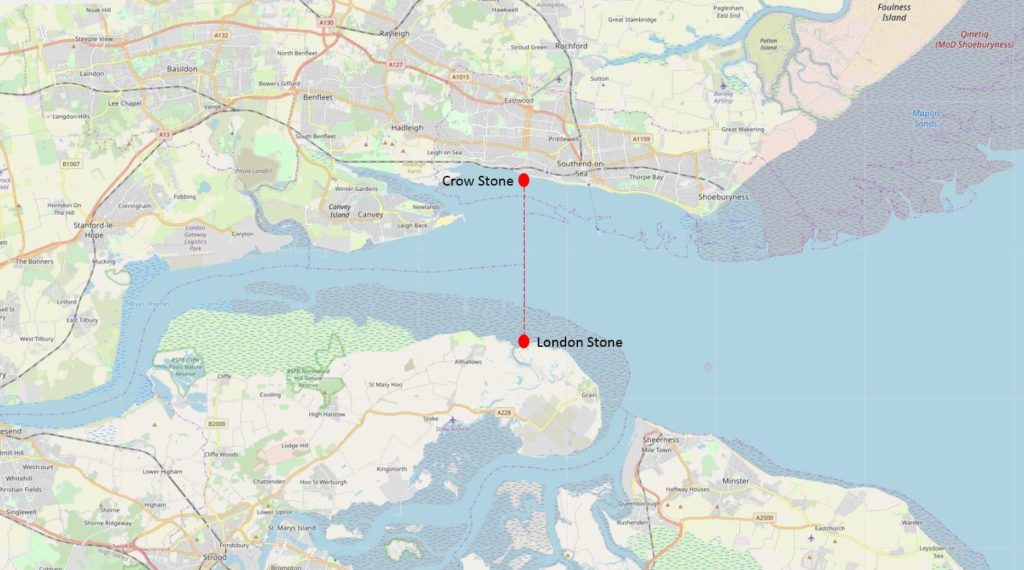

The following map shows the location of the stones and the imaginary line across the River Thames. Map extract (© OpenStreetMap contributors).

The City of London’s claim to the river this far out to the estuary, appears to date from around the late 12th century when the City of London purchased the right from Richard 1st in 1197.

This gave the City of London the ability to charge tolls, control activities such as fishing on the river and exercise other legal powers over river use, including navigation of the river. This control extended from the line between Southend and the Isle of Grain in the east, to Staines in the west. The City of London also tried to control part of the River Medway from where the southern end of Yantlet Creek reached the Medway, to Upnor on the boundary with Rochester.

The exact powers of the City and their ability to apply them to the River Thames and Medway were frequently in dispute, but the City continued till the 19th century to claim control, including renewing the stone markers as evidence of their rights.

My first visit was to the stone on the north bank of the River Thames.

The Crow Stone

The Crow Stone is easy to visit. To the west of Southend, on the boundary with Leigh on Sea and where the road that runs along the sea front turns inland at Chalkwell Avenue.

Walk over the embankment that forms the sea wall between beach and road, and providing you have timed the tide correctly, the Crow Stone can be seen a short distance out from the beach, and an easy walk over stones and gravel.

A short walk out to the stone, over a very firm layer of stone and gravel, with small pools of water the only indicators that this area was not long before, covered by the river.

The green algal growth on the Crow Stone shows the tidal range of the river.

It is very doubtful whether there were stone markers here dating back to the original purchase of the right by the City of London. The earliest tangible evidence is of a stone dating from 1755, although there may have been an earlier stone that had disappeared, prior to the mid 18th century replacement.

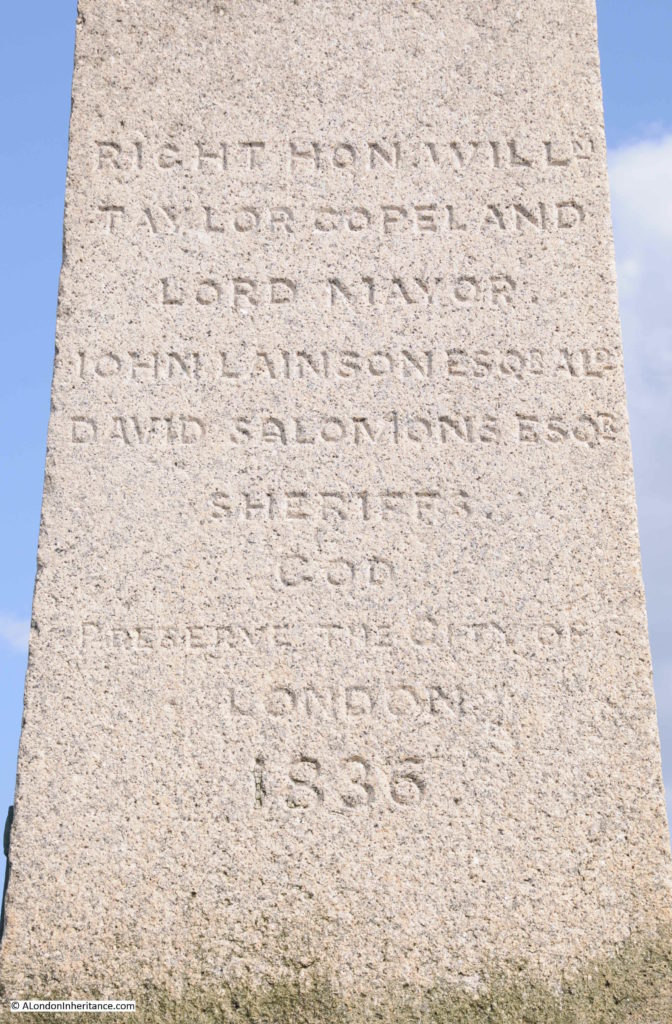

The current stone dates from the mid 1830s. The date on the stone is 1836, but a plaque on the stone erected by the Port of London Authority states 1837.

The view back towards land, showing the gradual rise in height as the shoreline reaches up to the land.

Carved on the Crow Stone are the names of the Lord Mayor, Alderman and Sheriff, although this adds further confusion as to the date the stone was erected, as the Lord Mayor named on the stone, William Taylor Copeland, was Lord Mayor in 1835.

The City of London, via the Lord Mayor and Alderman, would demonstrate their control of the river by visits to inspect the condition of the stones. These visits were major events, and the Illustrated London News describes a visit to the Crow Stone in 1849:

“CONSERVANCY OF THE RIVERS THAMES AND MEDWAY – The assertion of the Conservancy jurisdiction of the Lord Mayor over the River of Thames, and the Waters of Medway, or the View as it is technically termed, is a septennial custom attended with some interesting customs and celebrations, which falling due this year, has just contributed to the convivial memorabilia of the present Mayoralty.

This, by the way, is termed the Eastern Boundary of the jurisdiction, whilst the view from Kew to Staines is the western.

The jurisdiction appears to have been immemorially exercised over both the fisheries and navigation of a large portion of the Thames by the Mayor and Corporation of London; and we find an order dated 1405, issued from Sir John Woodcock, then Lord Mayor, enjoining the destruction of weirs and nets from Staines to the Medway, in consequence of the injury they did do the fishery and their obstruction to the navigation.

The portion of the river over which the jurisdiction of the River extended seems to have always been much the same. The offices of Meter and Conservator are asserted from Staines to the mouth of the Thames, by the formerly navigable creek of Yantlet, separating the Isle of Grain from the mainland of Kent, and on the north shore by the village of Leigh, in Essex, placed directly opposite and close to the lower extremity of Canvey island.”

These visits by the Mayor and Alderman seem to have been a good excuse for a party. The Illustrated London News goes on to describe the visit to the Crow Stone:

“THURSDAY, JULY 12, The company assembled on board the Meteor steamer, engaged for the occasion, moored off Brunswick Wharf, Blackwall. There were present the Lord Mayor and Lady Mayoress and a large party.

The steamer left Blackwall at about half-past eleven o’clock, and having received on board the Royal Marines band at Woolwich, the Meteor proceeded on her passage to Southend, the civic party being liberally welcomed with salutes and other respectful demonstrations.

At about three o’clock the Meteor arrived at Southend Pier, where the Lord Mayor, lady mayoress, and a large portion of the company landed. The Lord Mayor, attended by the Aldermen, the Town Clerk and Clerk of the Chamber, and some of the civic authorities, proceeded in carriages towards Leigh, nearly opposite to which the boundary stone is situated.

Here, by direction of his Lordship, the City colours and state sword were placed upon the stone, and after asserting his rights as Conservator of the River Thames, on behalf of the City of London, by prescription and usage from time immemorial, the Lord Mayor directed the Water Bailiff, as sub-conservator, to cause his name and the date of his visit to be inscribed on the boundary stone. The Lord Mayor then drank ‘God preserve the City of London’, the inscription on the ancient stone, and after distributing coin and wine to the spectators, the civic party returned to the steamer.

The stone itself was in the water, so that it had to be reached in boats. the scramble for the money was a rumbustious affair.”

The Lord Mayor’s order to the Water Bailiff to have his name and date of visit inscribed on the stone was carried out and the name of Sir James Duke (Lord Mayor between 1848 and 1849) can still be seen on the Crow Stone, along with the name of previous and following visits.

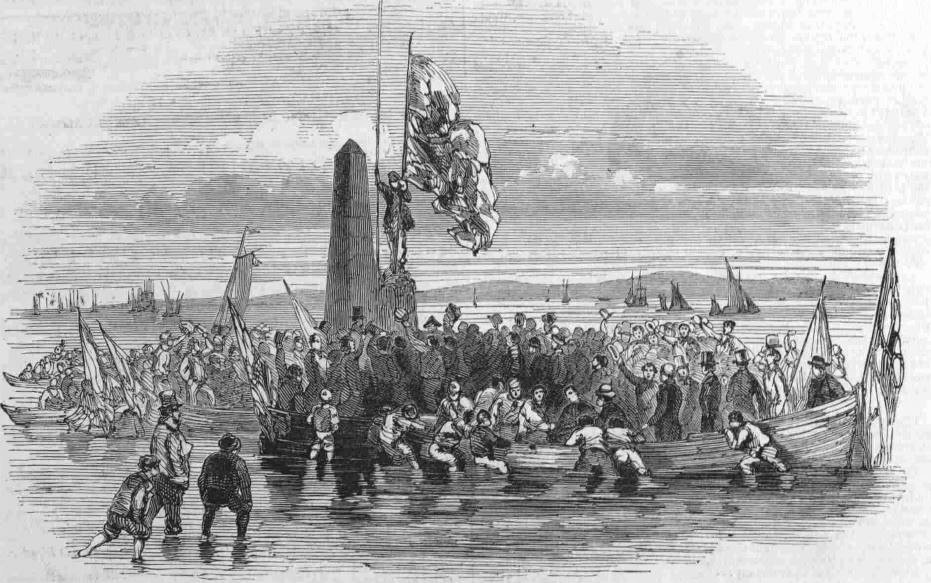

An illustration of the 1849 visit to the Crow Stone – it must have been quite a sight:

Note that in the above illustration, the man carrying what I assume to be the colours of the City of London is standing on a smaller pillar, adjacent to the Crow Stone, and it was this stone that I wanted to find next.

The earliest known boundary marker stone on the north bank of the Thames at Southend dates from 1755. It was removed from its original position next to the 1836 stone in 1950, when it was relocated to Priory Park in Southend, so that is where I headed to next.

The original Crow Stone:

This stone really does look like it has spent 200 years standing in the Thames Estuary, being battered by the wind and waves, and the daily movement of the tides.

The plaque on the current Crow Stone states this older version was erected on the 25th August 1755 by the Lord Mayor. The earliest written reference to the stone that I can find is from the Chelmsford Chronicle, dated the 18th July 1788, which carries a report of a body, sewn in a blanket, being found near the Crow Stone, washed up on the tide. It was assumed that the body was that of someone who had died on a ship and was buried at sea.

This report does confirm that the name Crow Stone was being used in the 18th century.

The stone in Priory Park has words carved into the stone, but these are very hard to read due to over 250 years of weathering, although as shown in the above photo, the cross from the coat of arms of the City of London is still clear, at the top of the stone.

Wording is carved onto multiple sides of the stone, and at the base of the stone is either evidence of repair work, or possibly the original fittings that held the stone onto a base.

So, Southend has two stones, one dating back to 1755, that mark the limit of the City of London’s jurisdiction over the River Thames. I next wanted to see the stone on the opposite side of the river.

The London Stone, Yantlet Creek

Marking the southern end of the line across the Thames from the Crow Stone is the London Stone by Yantlet Creek on the Isle of Grain.

The Isle of Grain is the eastern most section of the Hoo Peninsula in north Kent. The Isle was originally an island, with Yantlet Creek forming the western boundary. Parts of the creek have now silted up, so whilst difficult to get to (apart from the road on the southern edge of the peninsula), the Isle of Grain is not strictly an island.

The London Stone is not easy to get to. There are no footpaths to the stone, to the east of the stone is a large danger area as the land was once a military firing range. The south of the island has the remains of old power stations and new gas storage terminals.

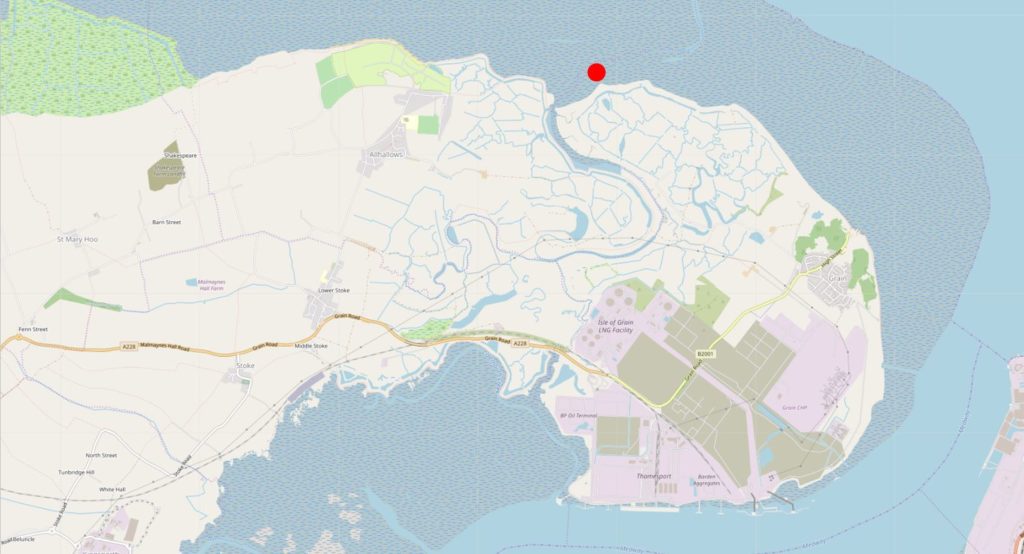

The only route that I could see that worked was from the west, then across Yantlet Creek at low tide. The following map shows the Hoo peninsula on the left, the Isle of Grain to the right, the red dot marks the location of the London Stone, and just to the left of the London Stone is Yantlet Creek. Map extract (© OpenStreetMap contributors)

Free time and tide times do not conspire to make life easy, so a couple of weeks ago I was on the edge of Yantlet Creek at 6:15 in the morning, ready to get across to the London Stone, and back again before the tide came in too far. The low tide was just before 7, so hopefully I had plenty of time to get across, look around the London Stone, and return before the water started to rise along Yantlet Creek.

The early 4 am start was well worth it – standing at the London Stone at 6:45 as the sun rose over the Thames Estuary, in such an isolated location, was rather magical.

As can be seen in the map at the start of the post, the Hoo Peninsula and the isle of Grain are very undeveloped, apart of the south of the isle where large gas storage holders can now be seen, and where coal fired power stations once operated.

The Yantlet Creek has long been a key point of reference on the River Thames, and there are numerous newspaper reports using Yantlet Creek as a reference for an event on the river, and the change in regulations that apply when crossing the line between Yantlet Creek and Southend.

For example, in April 1880, the Shipping and Mercantile Gazette had a report on the option for ships to change their navigation lights as they passed Yantlet Creek “Masters will not, probably, take advantage of the permission, when inward-bound, on reaching Yantlet Creek, at which point the river regulations come into force, of taking in their sea lanterns and exhibiting others”. The emphasis of the article was that whilst legally ships could switch to using lights with less visibility when passing Yantlet Creek, they would probably prefer to keep their sea lights on, which provided visibility of up to two miles – probably a wise move on a congested river at night.

Yantlet Creek was once a more significant feature than today, when it provided a navigable route between Thames and Medway, and turned the Isle of Grain into a true island.

The following map extract is from John Norden’s 1610 map of Essex. The map does show part of the northern coast of Kent along the Thames, and the Hoo Peninsula be seen, with Yantlet Creek running between Thames and Medway, cutting of the Grane Island from the rest of Kent.

The 1610 map also shows Alhalows, and it was from here that my walk to the London Stone commenced.

From the end of Avery Way there is a bridleway that runs up to the sea wall.

The bridleway runs over an area of flat pasture, with a herd of cows who look as if they are surprised to see someone at this time of the morning.

At the end of the bridleway, the land rises up to a footpath which runs along the top of the sea wall.

Although again, the cows do not seem happy to let me through.

Whilst the majority of the land is pasture, just before reaching the sea wall, there is a wide, water filled ditch with reeds that runs parallel to the sea wall.

Up on the sea wall, looking out to the estuary.

The Hoo peninsula and Isle of Grain are important habitats for birds. The RSPB has a reserve on the west of the peninsula at Cliffe Pools, and as I walked along the footpath, numerous birds flew up from the surrounding grassland, and there was the constant sound of birds on the mud flats of the estuary.

My first sight of the London Stone, to the left of the navigational marker at the entrance to Yantlet Creek.

Looking back over the Isle of Grain to large gas holders:

A better view of the London Stone as I get towards Yantlet Creek.

I like the above photo as it shows four ways in which the Thames Estuary has been used over the years. Closest is the navigational marker for the entrance to Yantlet Creek, further back is the London Stone.

Look between the London Stone and the navigation marker and you can just see the Shivering Sands, World War 2 sea fort. To the right of the navigational marker are the wind turbines of the Thanet wind farm. The photo also highlights the isolation of the London Stone.

As I walked around to the edge of the Yantlet Creek, it was starting to look worryingly wide.

In the grass adjacent to the creek is a stone with a rectangle where a plaque may once have been fixed.

I only found one reference to this in the wonderful Nature Girl blog, where there is a reference to this being a memorial to a young boy who drowned in the bay, and there having been a copper plaque on the stone.

A reminder that no matter how calm the estuary appears, this is always a dangerous place to venture.

The point where Yantlet Creek narrows and heads inland between the isle of Grain and the Hoo Peninsula:

It was here that I was able to find a way down the embankment, which was muddy, covered in seaweed and rather slippery, but I was able to cross over to the opposite shore.

It was still a short time to go before low tide and water was running out from Yantlet Creek towards the estuary. The above view also shows how deep the water will become when the tide comes in, and the flat nature of the mud flats mean that the tide can come in very rapidly and without too much warning.

The shore opposite was sand and stone, and provided a firm walking route to the London Stone, without having to leave the shore. The shore line curved round to what looked like a low peninsula with my destination at the tip.

The London Stone is a short distance out from the beach along which I had been walking. It had been built on a raised platform of stones, with a raised level of stones providing an easy walk out to the London Stone without having to venture into the surrounding mud.

Walking up to the London Stone. The obelisk is mounted on a square stone, which in turn sits on a plinth.

The view above is looking out over the Thames Estuary with the coast and buildings of Southend in the distance. It is just over 4 miles from here to Southend.

Most of the references I have read about the London Stone assume it is dated to 1856, and there is a very eroded date on the obelisk that looks like it could be 1856. There may also have been a previous stone marking the location. An article in the City Press from September 1858 provides some more background:

“THE NEW CONSERVANCY BOARD OF THE RIVER THAMES – During the past week, the Conservators of the River Thames visited the eastern limits of the Thames Conservancy and limits of the Port of London. The jurisdiction of the Conservancy extends to the eastward as far as the line drawn from Yantlet Creek , on the Kent shore, to Crow Stone, near Southend on the Essex shore, and the Port of London extends eastward as far as a line from near the North Foreland, on the Kentish shore, to the Naze of Harwich, on the Essex shore.

The ancient boundary stone near Yantlet Creek was found completely embedded in sand and shell. The Crow Stone on the Essex side, having been comparatively recently placed there, is a prominent object, and is discernible at a great distance.

It is the intention of the Conservators, we understand, to place a new stone on the site of the ancient stone at Yantlet.”

This article mentions the Thames Conservancy – this was the body who took over responsibility for the Thames from Staines to the Southend – Yantlet line from the City of London in 1857 under the Thames Conservancy Act. The article also mentions the Port of London, who have a far wider remit, extending much further out into the Thames Estuary – a responsibility carried out to this day by the Port of London Authority.

The article also mentions the ancient boundary stone being found embedded in sand and shell. I did wonder if it is still there, buried under the stones that support the London Stone we see today.

As with the Crow Stone, the London Stone has carved text, however erosion makes it almost impossible to read, however I suspect that it is a list of names from the City of London responsible for the erection of the new stone.

Supporting the obelisk, there is a square block of stone, with one side being carved with names. Despite at times being below the waterline, this block is easier to read, and contains a list of names of City Aldermen and Deputies. At the top of the list is the name of the Lord Mayor, Warren Stormes Hale, who was Lord Mayor of the City between 1864 / 1865.

The name of a Lord Mayor from 1864 / 5 adds further confusion to dating the London Stone, as we now have:

- References to the year 1856 as the date for the stone (for example English Heritage Research Report Series no. 16-2014)

- A newspaper article from 1858 stating that the ancient stone is covered and that a new stone is needed

- The name of a Lord Mayor from 1864/5 carved onto the base of the stone

So I am still not sure exactly when the London Stone was erected within a time range of 1856 to 1865.

Only the original Crow Stone at priory Park is Grade II listed. It appears the later Crow Stone and the London Stone are not protected, so over time they will gradually erode from the effects of weather and estuary water.

It really was a wonderful experience standing at the London Stone as the sun rose over the Thames Estuary, but it could have all been so very different.

Inner Thames Estuary Airport

The expansion of London’s airports has been rumbling on for decades, with an additional runway at Heathrow seeming to be the industry preferred selection, but one that was politically unacceptable.

The Thames Estuary has always been looked on as a potential site for a new airport. The estuary being just close enough to serve London, but remote enough to take away the noise of flights from over the city and suburbs, along with providing large areas of land for expansion.

One of the earliest was the 1970s proposal for an airport on Maplin Sands off the coast of Essex.

During his time as Mayor of London, Boris Johnson proposed and strongly supported the concept of an inner Thames Estuary Airport covering much of the isle of Grain, parts of the Hoo Peninsula, and the waters off the peninsula.

Plans were developed by the architect Sir Norman Foster, which proposed a massive airport in the estuary consisting of multiple runways, airport buildings and transport links to London and the rest of the national transport infrastructure. See illustrations of the airport here.

The illustrations show the airport, but the land on the rest of the peninsula appears untouched and ignore the amount of other infrastructure that would be required to serve the airport, and which would have obliterated the rest of the Hoo Peninsula.

I have added the outline of the airport to the following map. The red dot is the position of the London Stone, so where I was standing would have been in the middle of aircraft stands and gates, with multiple runways on either side. Map extract (© OpenStreetMap contributors)

Thankfully, the inner Thames Estuary Airport option was excluded from a shortlist of options by the 2014 Airports Commission report, chaired by Sir Howard Davies.

One of the reasons for excluding the airport given in the report was the rather pointed:

- There will be those who argue that the commission lacks ambition and imagination. We are ambitious for the right solution. The need for additional capacity is urgent. We need to focus on solutions which are deliverable, affordable, and set the right balance for the future of aviation in the UK

However given current politics, i would not be surprised if the proposal for an airport on the Isle of Grain and Hoo Peninsula gets resurrected.

Standing by the London Stone, as the sun rose, the distant sounds of the estuary, birds calling over land and water, it becomes very clear that an airport here would be a disaster.

I hope the following video provides an impression of this unique site.

The Crow Stone and London Stone are reminders of the City of London’s historical reach outside of the city, which as well as the Southend – Yantlet line also reaches out to Staines in the west, and included part of the River Medway. This post has been rather long, so I will cover the other stones at Upnor (River Medway) and Staines in future posts.

If you decide to visit the London Stone, then do so at your own risk and do not use this post as a guide – the estuary is a dangerous place.

Fascinating post and some excellent photos Many thanks.

A really wonderful post – the London Stone has been added to my ‘must visit’ list.

Crossing the Yantlet Creek looks decidedly tricky. Looking at the OS map and Google Earth, it appears that there is a proper crossing a mile or so upstream. Do you know if that’s accessible for those of us who are a bit less daring than you?

Thanks for the feedback Edward. There does indeed appear to be a proper crossing along the creek, however as far as I could tell, that is onto private land on the Isle of Grain, so I was not sure whether it would provide a route up to the London Stone.

Thanks. At least I know that if I do ever get across the creek, there is a way back, even if I have to talk my way out!

It’s always easier to exit via private land, what are they going to do? Keep you there!

I too was wondering if it would be possible to walk there via that direction. Has anyone tried it?

Hauntingly, atmospheric video at the end of a fascinating exploration of this bleakly beautiful area.

A fascinating read, in particular your journeys to the two stones, which must have taken very thorough research and planning, especially regarding tide times. I may get to see the north stone one day, but probably not the south stone! Top stuff…

Very interesting post , many thanks

What a marvellous description of the two stones which I’d never heard of. Many thanks Edward!

Brilliant. Thanks so much for all your posts. This was particularly good I hate to think of all hours of planning it must have taken – let alone the time to visit both places. Thanks again.

Something I never knew existed. Yes an airport here…..awful thought.

An interesting article. I have driven past the Crowe Stone many times so now know the reason why it is there & will go & take a closer look the next time I am in the area.

I may even consider searching out the London Stone as well

Absolutely fascinating read. Especially as a resident of Lower Upnor where we have the other Stone. The research you have done and the trouble you have been to get the photos too has my utmost respect. Would there be any objection to me sharing this article with my friends and local groups I know would be most interested? ( If I can work out the best way.)

Thanks again

Hi Lindsay – I was at the Upnor stones a couple of days ago, a lovely part of the world. Very happy for you to share the article.

I suppose Mr Johnson still thinks we can just build an airport over the SS “Richard Montgomery”?

Glad you’ve made me look it up: I hadn’t realised it had come up again in the House of Lords, just a couple of months ago.

https://www.theyworkforyou.com/lords/?id=2019-07-03a.1499.0

Look out for Crowstone beer on your travels (often at the Mayflower pub, Leigh on Sea)

http://leighonseabrewery.co.uk/

A great highlight on the damage that would be carried out by the building in this area by a 3rd airport.

As a young man living in the East End of London (Wapping) I had a Thames lighterman friend who would mention these boundaries, although I didn’t know that they were physically marked. Does anyone know what significance these boudaries would have to London lighterage?

If the Maplin Sands airport and seaport had been developed it would have saved the U.K. and especially the area round London of almost 50 years of political conflicts about how to airport development.

I live a stone’s throw — excuse the pun — away from Priory Park but never realised the original Crowstone was there – will have to take a look some day.

Very interesting. You might also like to read about the Ray and Benfleet Creek on the Benfleet Yacht Club website. The Crowstone is important here too! Look for the pdf under navigation charts at the bottom of the first page.

Reading this article when it was first published kind of spurred me on start a photographic project that I’d had in my head for a while… ever since, I have been documenting the Crowstone, its interactivity with the public, and the changing tides, seasons and weather. If anyone’s interested in seeing it, I’ve now made the work live on my website at https://www.markmassey.co.uk/the-crowstone – thank you for the inspiration!

The London Stone is ‘listed’ at grade II, I believe the designation was made in 2015.

I’m in some awe of our author as many times have I stood on the Western bank of Yantlet Creek and yearned to visit London Stone. Yet, not once have I had the nerve to test the mud for its supportive value. An incident East of Gillingham left me in no doubt of the dangers of being stuck in the mud against a rising tide.

Thank you for enabling me to visit the two stones ‘with you’ via your research and video. I was born in north Kent but had not heard of the London Stone until I read about it in Tom Chessyre’s visit to the stone on the Grain marshes on his walk along the Thames in his book From Source to Sea. An interesting book (not as funny as Bill Bryson!) but suits armchair travelling during these Lockdowns!

Does anyone know where the term “Crow” came from? Our local rag published a write up on the local Crow Stone at Chalkwell Essex and I wondered why it was called ‘Crow Stone’? Where did the Crow come from? Some say there was a tenement near by the London stone so they named it so? Some say a resting place for crows which seems daft as Ive not seen crows by the sea! lol.