At the end of the last war there were a number of booklets published by different Government Departments – the Metropolitan Police, the Post Office, British Railways and some of the London Boroughs. My father seems to have purchased a number of these as they were published, and this week I want to feature one of the booklets published in 1946 by a London Borough, with the title “Bethnal Green’s Ordeal”.

The booklet was published by the Council of the Metropolitan Borough of Bethnal Green and is a very slim, fifteen page account of Bethnal Green during the war. Written by George F. Vale, who had previously written a pre-war book about Bethnal Green, so I assume was a local resident. The booklet covers 1939 to 1945, but starts with preparations in 1938.

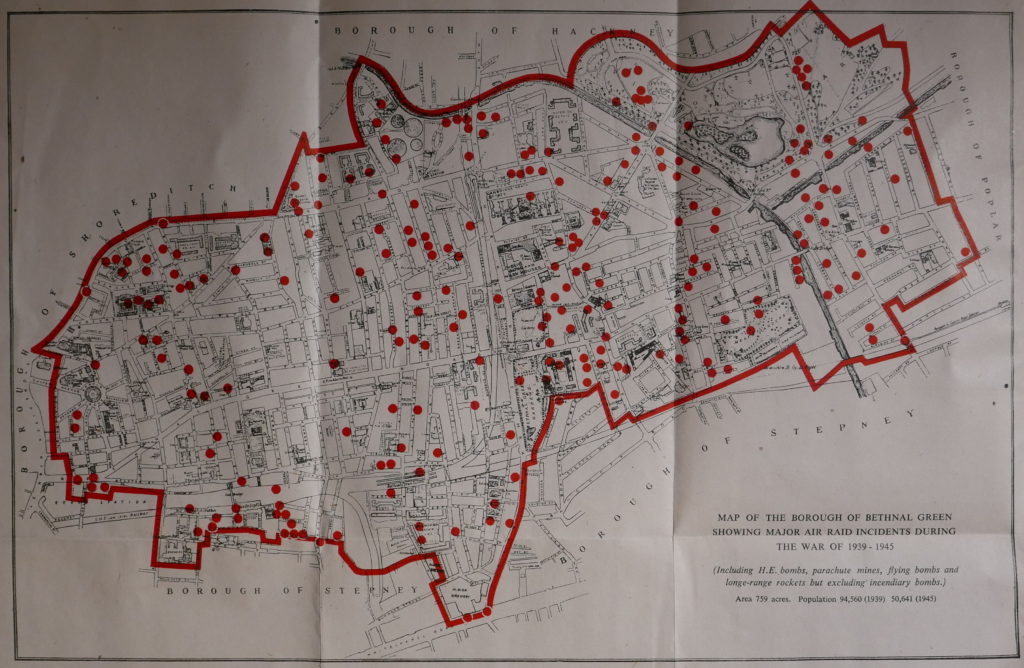

The booklet also includes a fold-out map showing the Borough of Bethnal Green with the location of major air raid incidents marked in red. Each dot represents a high explosive bomb, a parachute mine, flying bomb (V1) and long-range rocket (V2), but excludes incendiary bombs. (Click on the map to open a larger version)

Note in the bottom right hand corner the impact of the war on the population of Bethnal Green, with a population of 94,560 in 1939 falling almost by half to 50,641 in 1945.

Starting in 1938, we discover that 66,828 gas masks were issued to the residents of Bethnal Green on Wednesday and Thursday the 28th and 29th of September. This was followed by a period of comparative calm, until the war came to Bethnal Green with a vengance in August 1940:

“On Saturday night and in the early hours of Sunday morning, the 24th and 25th August 1940, the storm broke and we in Bethnal Green had some ideas of the dangers that lay ahead. Our baptism of fire consisted of several high explosive bombs each weighing 50 kilograms which were scattered over a fairly large area of the borough, extending almost in a line from The Queen Elizabeth Hospital in Hackney Road to Lessada Street, east of the Regent’s Canal in Roman Road.”

The raids continued through September between Saturday 7th September and the 24th of September 1940, when 95 high explosive bombs, two parachute mines and literally thousands of incendiary bombs fell on Bethnal Green.

“No part of the district escaped this terrible holocaust. Bethnal Green Hospital, The Queen Elizabeth Hospital, the Central Library, Columbia market, the Power Station in Bethnal Green Road, the Hadrian Estate, the Burnham Estate, the Vaughan Estate and the Bethnal Green Estate were all hit, whilst the parish church of St. Matthew’s and St. Paul’s Church in Gosset Street were totally destroyed. On that night too, Columbia Market, which contained a very large public shelter was the scene of a very distressing calamity when a 50 kilogram bomb, by a million to one chance, entered the shelter by means of a ventilating shaft and caused extensive casualties to those sheltering.”

Thirty eight people were killed by the bomb on the Columbia Market shelter.

The booklet provides details that help understand Bethnal Green at the time. For example, there were still a number of stables across the Borough, and one of these, the Great Eastern Stables in Hare Marsh was hit and several horses were trapped and needed to be put down.

The composition of road surfaces amplified the impact of incendiary bombs as many were still covered by wooden blocks: “On the night of December 11th 1940, more fires were gaining hold on Bethnal Green than ever before. The area at the west end of Bethnal Green Road was a sea of flames, the wooden blocks which surfaced the road themselves catching fire and burning through almost to the concrete underneath.”

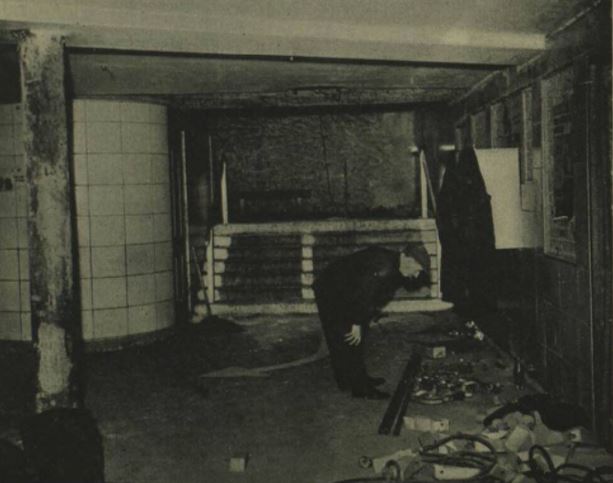

The booklet has a page covering the disaster at the Bethnal Green Underground Station. This was being used as a shelter and was one of the largest in London capable of accomodating 10,000 people.

The shelter was opened very rapidly in 1940 at the persistence of Herbert Morrison, the Minister of Home Security. The Sunday Mirror on the 6th October 1940 reported:

“The Man Who Gets Things Done – Herbert Morrison, new Minister of Home Security, beloved by Londoners, is the man who gets things done.

Standing on the platform of the uncompleted Bethnal Green Underground station, 65ft below ground yesterday, he asked L.P.T.B and local council officials why it was not being used as a shelter.

He was told there were certain technical difficulties. ‘Is there anything to stop the people using it right away?’ he queried brusquely. He was told there were not.

‘Then open it tonight’ said Herbert Morrison.

That is why several thousand men, women and children of the East End who last night found sanctuary in the station and tunnels – part of the new Tube extension not yet in use – bless the name of Britain’s ‘livest’ Cabinet Minister.

A.A. Shells were bursting in the sky during an alert when Mr Morrison and Admiral Sir Edward Evans arrived to inspect the station. Mr Morrison, after chatting with the experts, reached his decision about the opening of the station as a shelter in five minutes,

Council officials told him that everything was ready to make the shelter comfortable.

Someone said the pit in the concrete track should be boarded over. ‘Let them sleep on the track’ replied Morrison.

Mr Morrison said in an interview: ‘You can tell the people we are going to utilise every inch of shelter we can find and we’re going to do it quickly’

The booklet describes the Bethnal Green Underground shelter:

“It had a sheltering capacity of 10,000; the highest figure reached was 7,000 in 1940-1 and in the summer of 1944 during the flying bomb raids. The Tube played a great part in the life – at night and in times of danger – of a great number of people in Bethnal Green; particularly the old people and mothers with children. It was provided with a canteen, a sick bay with a trained nurse regularly in attendance, a visiting doctor, a concert hall capable of holding 300 people and a complete branch public library consisting of 4,000 volumes.”

The worst civilian disaster of the war happened at Bethnal Green Underground station on the 3rd March 1943. The booklet records:

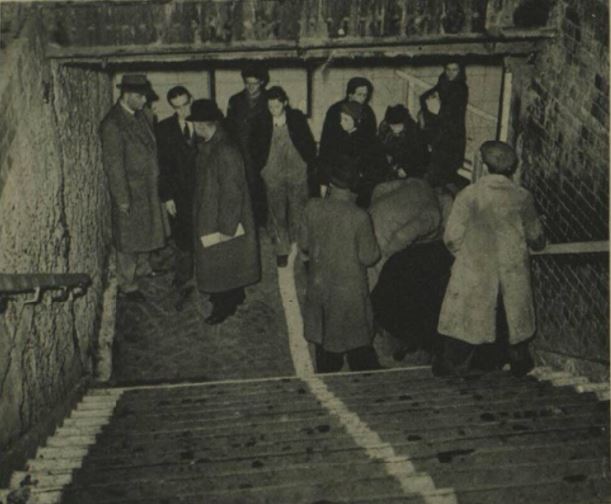

“On the night of the 3rd March the warning went at 8:17 p.m. and almost immediately hundreds of people were seen to be making for the shelter from all directions. It is estimated that in the first ten minutes after the sirens had sounded 1,500 people were admitted. Everything was normal and although the people were obviously anxious to get under cover there was no undue haste or panic, when suddenly, without any kind of preliminary warning, at 8.27 p.m. a salvo of rockets was discharged from a battery in Victoria Park. The shattering noise created by this operation undoubtedly caused the already anxious people to redouble their efforts to get into the shelter.

Unfortunately the reports of the guns were thought by many to be the sound of exploding bombs. At this critical moment it is said that a women, with a child, or a bundle, or perhaps both in her arms, fell on the stairs. So great was the pressure of the crowds behind her that in the matter of a few seconds there was a solid mass of bodies, piled up five or six deep, against which the people seeking admission and not knowing of the accident, still endeavoured to force an entrance.

On the instructions of the Home Secretary, Mr Herbert Morrison, a full enquiry into the circumstances of the accident was conducted by Mr. Laurence Rivers Dunne, M.C. one of the Magistrates of the Police courts of the Metropolis. The enquiry lasted from the 11th to the 17th March inclusive and in all eighty witnesses were examined. His final conclusions were:

(a) This disaster was caused by a number of people losing their self control at a particular unfortunate place and time.

(b) No forethought in the matter of structural design or practicable police supervision can be any real safeguard against the effects of a loss of self control by a crowd. The surest protection must always be that self control and practical common sense, the display of which has hitherto prevented the people of this country being the victims of countless similar disasters.”

The report appeared to put the blame on the people attempting to enter the shelter and their loss of control.

In reality, the entrance to the stairs down to the shelter were poorly lit, there was no central handrail and insufficient police or wardens to manage access to the shelter.

The Illustrated London News on the 13th March 1943 published an account of the tragedy and published photos of the entrance showing only side handrails and the general poor condition of the entrance.

It is easy to imagine how simple it would be for someone to stumble and fall in a crowd, and the impact that would have in such a confined entrance with no safety features.

The Illustrated London News report states that there were no bombs and no panic, and makes no mention of the salvo of rockets. An apparent contradiction to the report by Rivers Dunne, and despite the report stating that “No forethought in the matter of structural design ” could have avoided the tragedy, immediately after the tragedy, steps were taken to improve lighting, add handrails and barriers to shelter enhances, perhaps an acknowledgement of the contribution that the lack of these features had to the Bethnal Green tragedy.

173 people of all ages died on the 3rd March 1943 at the entrance to the Bethnal Green Underground shelter.

The entrance today – the woman fell at the bottom of the first flight of stairs:

A plaque recording the tragedy above the stairs:

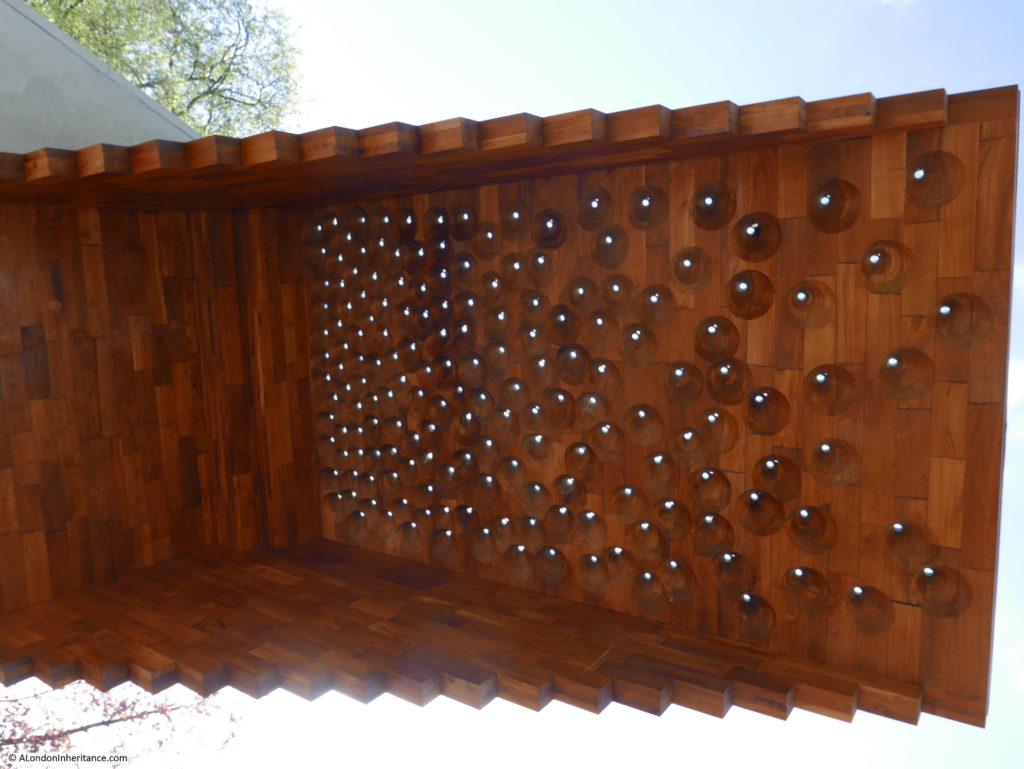

A memorial to the disaster was completed in December 2017:

The memorial is located by the entrance involved in the disaster and represents the stairs down from the street, with the names of those killed carved into the side of the memorial:

There are 173 small conical light shafts cut into the top of the memorial, and these are clustered closer together as the end wall is approached – representative of the way the tragedy unfolded:

The full names and age of those who perished are recorded on the upright support of the memorial. The repetition of the same surname, and the numbers of children involved shows the terrible impact that the tragedy must have had on individual family’s.

The memorial is a very fitting reminder of the tragedy at Bethnal Green Underground station in 1943.

One final comment on the tragedy comes again from the booklet and highlights the impact that war had on children:

“Some reference must be made to the work performed by the boys at the tragic Tube Shelter disaster. They helped with the injured and saw sights which probably no boy of such tender years has been called upon to experience. One boy was found by the Controller at the mortuary helping to unload the dead as they were brought from the scene of the disaster. The Controller said to him, ‘Don’t you feel somewhat upset by this?’ and the boy answered, ‘Well, Sir, I was sick when I first started, then I got over it, and anyway the job has got to be done.”

The remainder of 1943 and early 1944 was generally quiet in Bethnal Green, however Bethnal Green’s ordeal continued on the 13th June 1944 when a flying bomb fell in Grove Road. A total of twenty V1 flying bombs would fall on Bethnal Green.

These would be followed by the V2 rocket, with the first falling in Lessada Street in November 1944, the second in Parmiter Street in February 1945 and the final rocket just outside the borough boundary in Vallance Road in March 1945.

The booklet illustrates the effort needed by the Council and volunteers to respond to the bombing of Bethnal Green. The Borough Council had to arrange the clearance of 4,550 homes, providing storage space for the furniture from 1,350 and moving the furniture from 2,200 other homes to alternative accommodation.

Those too young to be conscripted into the armed forces were involved in a number of activities. Boys were used for multiple roles, acting as messengers, filling sand bags, installing blast walls at the London Chest Hospital, and it was the Scouts who erected the 5,000 bunks in the Bethnal Green Underground station shelter. Although evacuation of children from the city had started at the beginning of the war, the booklet records that a large number of children had drifted back to their homes and families in Bethnal Green. (This was also my father’s experience, as he only lasted three weeks after evacuation before returning home to the city).

The task of looking after and identification of so many dead civilians was a challenge for a single Borough. Of the 555 civilians killed during the war in Bethnal Green, there were 23 unidentified or unclaimed. These were buried in the communal grave at the City of London Cemetery, Manor Park.

Bethnal Green’s Ordeal also highlights the impact on the population of day to day precautions. For example, the black out came into full force on Friday 1st September 1939 and is recorded as being one of the war time restrictions that was the most difficult to bear. “It was easy to appreciate its importance during actual raids, but the hours of darkness were so many, especially during the long winter nights – many of which were raidless – that at times the depressing effects of the black-out were almost unbearable.”

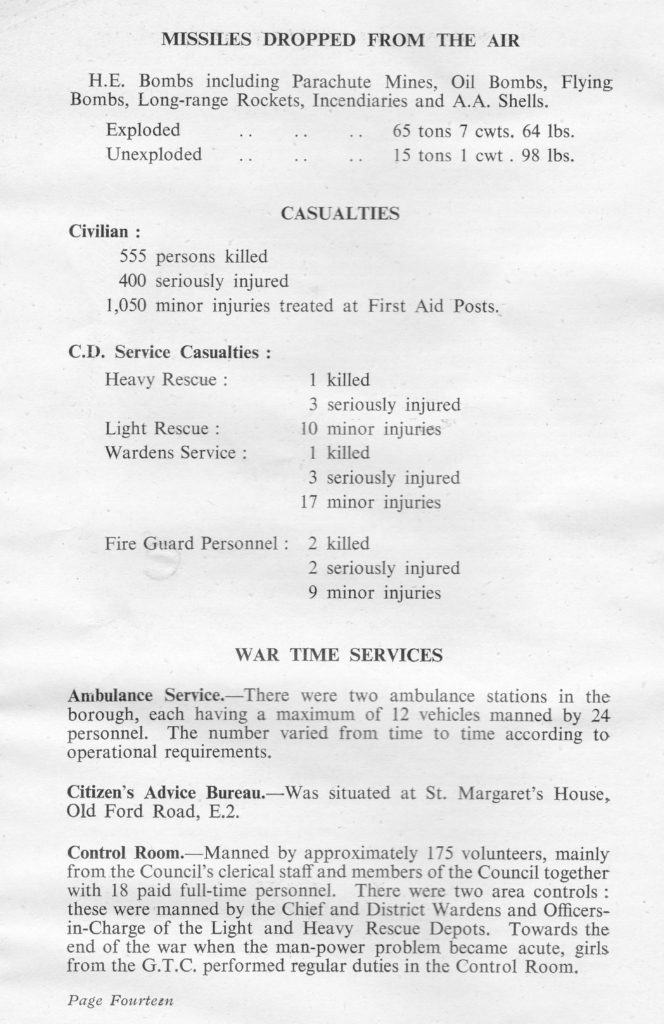

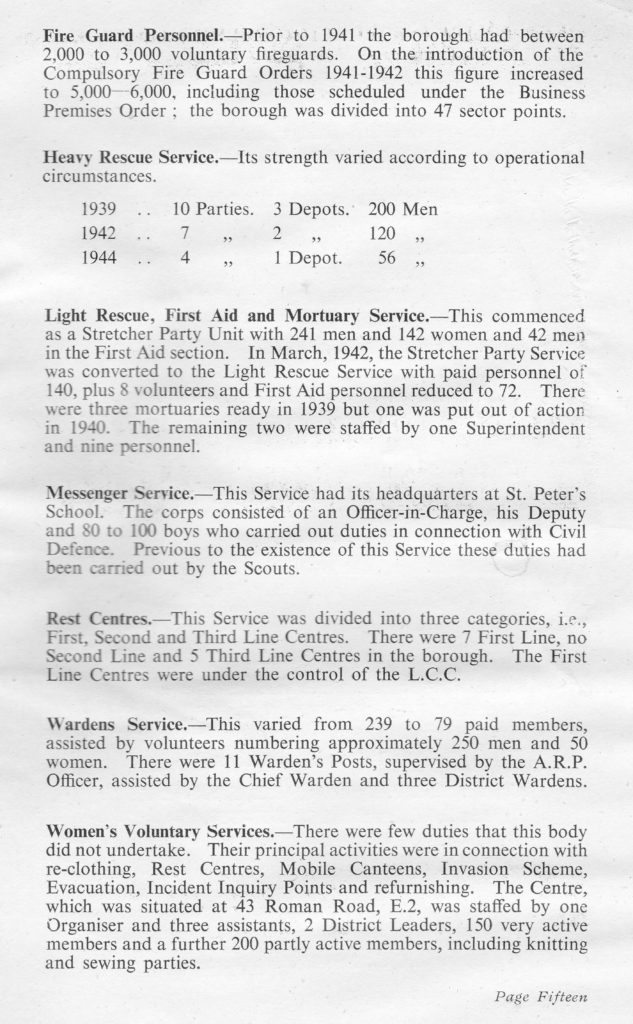

The booklet ends with two pages that provide some key statistics, and details of the organisations that developed within the borough to manage the impact of the war.

The memorial at the entrance to the Underground station is a reminder of the dreadful tragedy of one single event. The booklet is a reminder of the overall impact to one London Borough as summed up by the final paragraph in the booklet::

“Thus ends the story, perhaps rather fragmentary, of what an ordinary typical East End borough endured during the war years. It is hoped that it will serve as a reminder to the present generation and as a record for posterity of Bethnal Green’s Ordeal, 1939 – 1945.”

Another great article. Thank you.

Thanks

Thanks again for such an interesting piece.

It appears that George F. Vale was probably the Borough Librarian in Bethnal Green as someone of that name and occupation is listed in the 1939 Register, compiled when Identity cards were being issued in September of that year. He was born in 15 August 1890 and was living at 57 Broadwalk, Wanstead with his wife Annie when the register was compiled. He was also noted as ‘Civil Defence D.F.E.O.’

Anne, thanks for the information on George Vale. That would make sense, the perfect role for someone to author the book on Bethnal Green.

It seems George was born in Bethnal Green, his father died when he was young and he grew up in Mile End Old Town, moving out to Homerton later. He married in 1914 and had three daughters.

George and Annie were my Great Grandparents

You are correct Anne, George was indeed Chief Librarian of Bethnal Green. He was later made a Freeman of the City of London. He passed away in 1960 at home in Theydon Bois, where they had moved to after the war. Their daughters were Joan, Gwen & Enid – all have sadly passed away now. Gwen was my mother.

I hope you will be able to share other gems from your father’s archive. This really is wonderful stuff.

When I was a young traffic Police Officer, stationed at Bow Police Traffic garage I was told by one of the older officers that Bethnal Green tube station was haunted by the ghosts of those unfortunates that were killed there in the blitz. He said that when he was on foot duty one late evening in the Bethnal Green road, he was approached by a man in a great state of shock. The man told the officer that he had heard the sounds of children crying and men and women screaming, coming from the entrance to the tube station. The officer tried to get him to come back to the entrance but man refused and ran off. On the officers return to Bethnal Green nick, he enquired with his sergeant if he should report it. The sergeant told him that he had heard of many reports and not to bother.

In this age of the internet I found this …. https://secretldn.com/haunted-underground-stations/

There have been some ghostly goings on out in the East End, and there’s a truly sad history behind them. Workers at Bethnal Green station have heard children sobbing, women screaming, and the general sound of panic. Usually, this starts quietly and then rises to the sound of a cacophony, leaving anyone who hears it understandably terrified.

It can all be traced back to a dark night in March 1943. As one of the deepest stations in East London, Bethnal Green was doubling as an air raid shelter when the Luftwaffe circled for an attack. Hearing sirens, residents streamed down the steps into the supposed safety of the station. Tragedy struck when an anti-aircraft gun went off nearby, and started a panicked rush which led to a stampede. 173 people died in the ensuing crush, and the screams still echo around Bethnal Green today.

This has been another interesting read,Admin. So much so that we have put Bethnal Green Station on our ‘to be visited ‘ list. Do you or any of your followers know,if there was a similar information booklet published on the wartime experiences of Bermondsey?

Thank you for a very interesting article about Bethnal Green during the Second World War. My parental grandparents at the time lived in Viaduct Strret which is off the Bethnal Green Road and quite near Bethnal Green Station. Perhaps, they used the station when it was an air raid shelter.

In Victorian maps of London, a tunnel is shown going north from south of the viaduct from Liverpool Street to East Anglia towards Cambridge Heath Station. It appears in the Ordanance Survey map of 1895 going north under Mape Street much of which was demolished along with Viaduct Street to form Weavers Field Park. Has anybody any information about the tunnel which seems to have been forgotten?

An extremely interesting article, I visit this spot regularly as I visit the V&A children’s museum a lot and we always spend a moment at the memorial.

Do you know if leaflets were produced for other London areas? I have seen the large map that was used at Leytonstone Police station marking Luftwaffe hits from incendiary devices to V2 it is kept in store at the Vestry house museum……..once again thank you

@ Charles

There is a tunnel south of the viaduct, which appears to go under the viaduct in the direction of following under Mape Rd. However this is a dead end that stops at the viaduct.

Zooming in on the 1895 map below shows the following:

The area marked tunnel is on what appears to be sidings on the East London Railway. The sidings are in a cutting that continues into the tunnel under the tracks above that terminate at Spitalfields coal depot. The tunnel ends just before the viaduct and the short open section shows what appear to be the end of two siding tracks.

http://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=17&lat=51.5234&lon=-0.0631&layers=163&b=5

Apparently it was planned to extend to Cambridge Heath to connect with the Great Eastern railway to transfer coal from the GER to the ELR, but that never happened. Coal transfer being transferred by hoists at Spitalfields instead. These are shown on the 1913 OS map and also on the 1949 OS map, but for some reason, the 1949 map series doesn’t show tunnels!

http://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=18&lat=51.5223&lon=-0.0633&layers=173&b=1

Also see Wiki – East London Line

Many thanks for the information about the planned tunnel which was never built. On Victorian maps prior to 1895 it is shown going up to Cambridge Heath Station too.

If it had been built it could have served as an air raid shelter during the Second World War.

a very interesting and sad post, terrible what happened to all these people at Bethnal Green.

MY parents and grandparents–all from Bethnal Green–my Dad was an Air Raid Warden -Alfred William Wood at the start of WWII but then got called up to serve in the 8th army royal engineers in North Africa—my parents told me a few stories about the Blitz and my Mum had been evacuated in 1939 to Somerset with my 2 older sisters both small children–all my grandparents stayed in BG throughout the war—-I was born in Somerset Post war but remember the stories told to me about London and the Blitz–many family were from Bethnal green—thank you for this informative article—kind regards Sheila E Wood

Of admittedly minor importance, I have just received a copy of the front of the booklet since it was my uncle (my mum’s brother) who painted it. He was James Cordwell. His initials can be seen on the cover. Uncle Jim was an assistant borough surveyor who lived in Old Ford Road. His own father, Harry (Henry) Cordwell, a resident of Angela Street Columbia Road Bethnal Green died as a result of enemy action on Saturday 11th January 1941 aged 62.

Presumably George knew of James’ artistic ability.

An excellent and very interesting read.

David Purvis

I am Jim’s great-granddaughter, and he was a skilled artist. My grandma Marlene had many of his pieces, and it is saddening to have relatives lost by The Blitz.

From the USA,

Catherine

Can anyone please advise the location of 1 Bullen House , Bethnal Green please. According to my mothers WW2 ID Card ( Hilda Helen Smith nee Britton ) she was living there during 1945-6-7 & possibly her grandparents ( the Harwoods on her mothers side ) home as she was possibly caring for her infirm grandmother at this time. Any help would be greatly appreciated. Thanks .

John, Bullen House is alongside Collingwood Street in Bethnal Green. If you look for Collingwood Street on Google Maps and use street view, you can see the flats.

My grandfather had a clothing factory prior to, during and after the war. It was located at 283 Bethnal Green Road, suffered severe bomb damage and it had to be rebuilt.

On the map which accompanies the original text, there is no evidence of a bomb landing on the site – it was described as the penultimate flying bomb – and I wonder whether there might be anyone able to confirm this report.

Thank you.

Have you got the building no. correct?

The 1949 OS map shows a cinema at 281 – 285 Bethnal Green Road:

https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=19&lat=51.52655&lon=-0.06604&layers=170&b=1

Are you sure that 823 is the correct building no,?

The 1949 OS map shows 281 – 285 as a cenema

https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=19&lat=51.52655&lon=-0.06604&layers=170&b=1

Ignore the earlier double post – I did’t think the first one was posted and then I screwed up the building no. on the second!

I’ve looked around, and can’t find any reference to V2 hits at or near Bethnal Green Road. Only 2 V2s are shown / listed for the Bethnal Green area, and these are also shown on the LCC Bomb Damage Maps:

1 Centred on Totty Street and Lassada Street, south of Roman Road between Regents Canal and Grove Road. Showing prefabs on the 1949 map, the area was later cleared and became the green area that includes the Ecology Pavillion.

2 Bishops Road – between Bishops Road and Parmitter St. Again, the site was then then cleared and laid out with prefabs, before becoming blocks of flats. According to the LCC Maps, the centre of the hit is approximately where Charmeuse Court is today.

Both these hits are shown on the Bethnal Green map, but are not specifically identified as V2.

Looking at the LCC Bomb Damage Maps, along the Bethnal Green Road and facing the road, there are two major areas shown as Damaged Beyond Repair:

1 Between Satchwell Road and Turin St. Buildings affected were probably 187 – 225 according to the 1949 map. 181-185 and 227–235 are shown as just having general blast damage.

2 West area, near where BGRd begins. Mainly the two triangular areas shown on the map around Club Row, Cygnet St and the facing area between Cygnet St and Brick Lane. These are the cleared areas on the 1949 map. Strangely, the BG map doesn’t show any bomb hits on that area, but shows four just to the west. The LCC map shows little damage where the four bombs are shown.

BGRd appears to have been generally unscathed.

401 – 429 are classed by LCC as General Blast Damage – not structural, although on the 1949 map, 387-389, 405, 409-419 are missing, so presumed demolished and site cleared for whatever reason. The area behind these buildings suffered the most damage, especially between Canrobert St and Wolverton St. where two of the hits are shown on the BG map.

Thank you for your detailed reply.

However, I am concerned not with Bethnal Green Road, but round the corner in CAMBRIDGE HEATH ROAD, although I cannot see any damage on the map that was concerned with nos 283 and 295. The latter property was opposite one of the entrances to the Bethnal Green Undergound Station. #283 was opposite the Bethnal Green Library, a good and well-equipped reference library. #283 was also next to the London Electricity Board showroom and eventually became a “show house” for the various heating appliances available from the Board.

It, # 283, is now (2020) an hotel, or at least was last year when I went to take photos of it!.

Found it 🙂

There are three things that threw me:

1 I was specifically looking at Bethnal Green Road

2 The V2 hit wasn’t shown on the wrsonline V2 rocket map

3 Cambridge Heath Road is just over on the next LCC map and I missed it!

The LCC map shows the V2 hit as being near the Cambridge Heath Rd edge of Bethnal Green Gardens, approximately opposite no. 269 Cambridge Heath Rd (I don’t know how accurately the position is pinpointed).

The Bethnal Green map shows the red spot in on Bethnal Green Gardens at about the right place.

Whilst the 1895 map doesn’t show building nos., comparing the nos. shown on the 1949 map (253 for the pub on Birkbeck St.) to the next no. shown (283), each building on the 1895 map would match up if they are numbered in sequence. 267 and 269 are opposite the ‘A’ of Cambridge Rd on the 1895 map.:

https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=17&lat=51.52686&lon=-0.05503&layers=163&b=1

The LCC map shows the following damage:

297-303 – no damage

283-289 – Seriously Damaged doubtful if repairable

291+295 – Damaged beyond repair. Surprisingly, 293 (next to the alleyway) is shown as OK (unless it was missed out).

From 281 down to Birkbeck St., and the north side of Birkbeck St, all buildings are either shown as Damaged Beyond Repair or Total Destruction.

South of Birkbeck St, most of the area between Cambridge Heath Road and the two railway lines is shown as mostly major damage. The lower half of this being due to a V1 hit around Abingdon St.

Google Earth 1945 historical imagery shows the cleared areas, with what appears to be 283-289 and those near Bethnal Green Rd still standing.

Regarding no. 283 being a hotel, the hotel is actually no.287 and is shown as the Green Man pub on the OS maps. 283 appears to be two houses down from the hotel.

Details are take from current Google Streetview images (5/2019). I’m assuming original by what little I can see from the images.

Going south from Bethnal Green Road, the buildings are:

303 Dimi’s unisex salon – original

301 Offie & Toffee – original

299 Starbucks – original

297 Stephanie’s – original

295 Ladbrokes – original or rebuilt to look like the original?

293 Sainsburys – 291, 293 + alleyway combined in new building

289 New life Church – rebuild

287 City view hotel (was Green Man pub) – original 1882) building

285 house

283 house – rebuild?

Regarding 283, in your original comment, you said that 283 was rebuilt. Purely by looking at Streetview, that could well be the case as the front is different compared to its neighbour 285 which looks more like an original building.

Going by the 1895 map, it looks as though 283 and 285 were always houses as the map shows the front steps and gardens. Depending on the size of the factory, I suppose the building could have been used as a factory or the factory was an adjacent building.