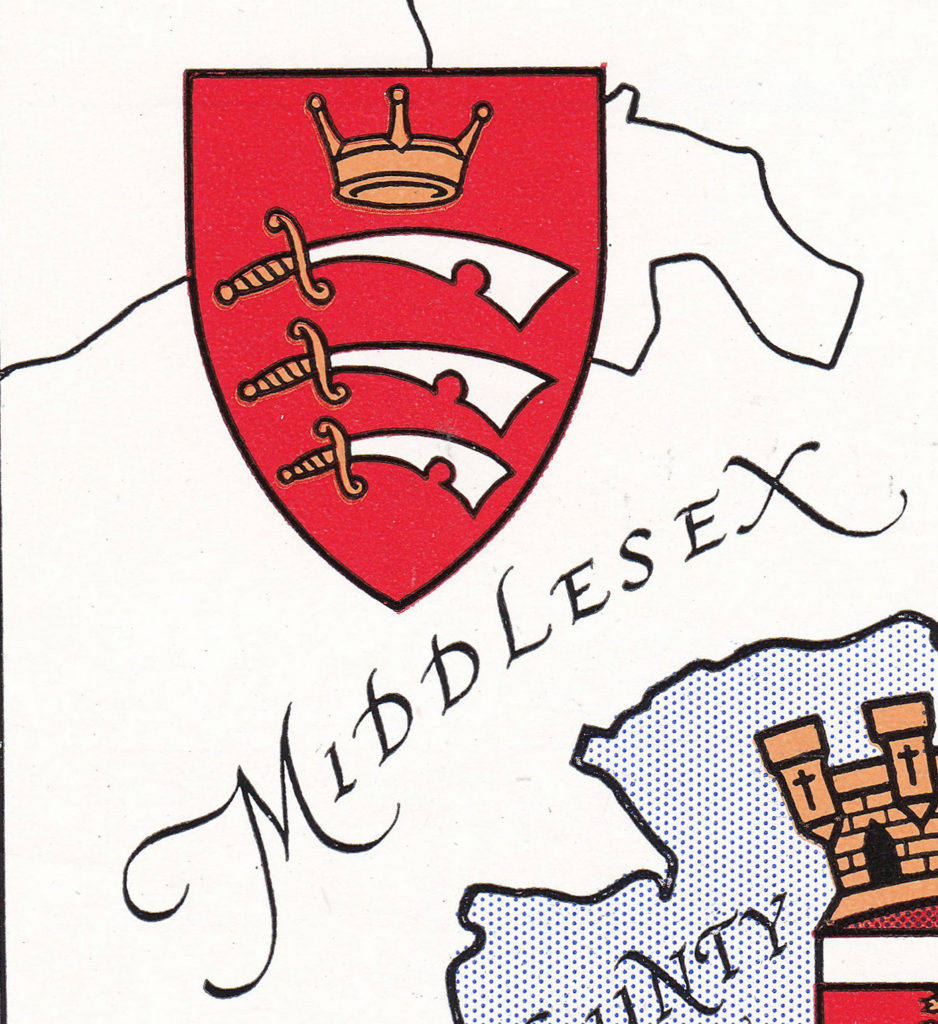

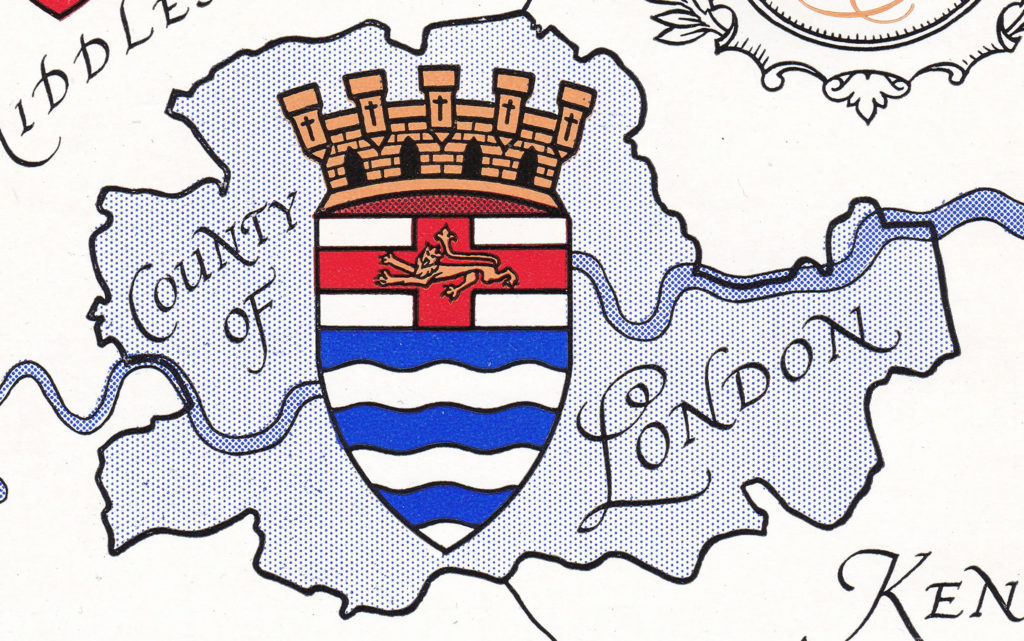

At the end of the last war there were a number of booklets published by different Government Departments – the Metropolitan Police, the Post Office, British Railways and some of the London Boroughs. My father seems to have purchased a number of these as they were published, and this week I want to feature one of the booklets published in 1946 by a London Borough, with the title “Bethnal Green’s Ordeal”.

The booklet was published by the Council of the Metropolitan Borough of Bethnal Green and is a very slim, fifteen page account of Bethnal Green during the war. Written by George F. Vale, who had previously written a pre-war book about Bethnal Green, so I assume was a local resident. The booklet covers 1939 to 1945, but starts with preparations in 1938.

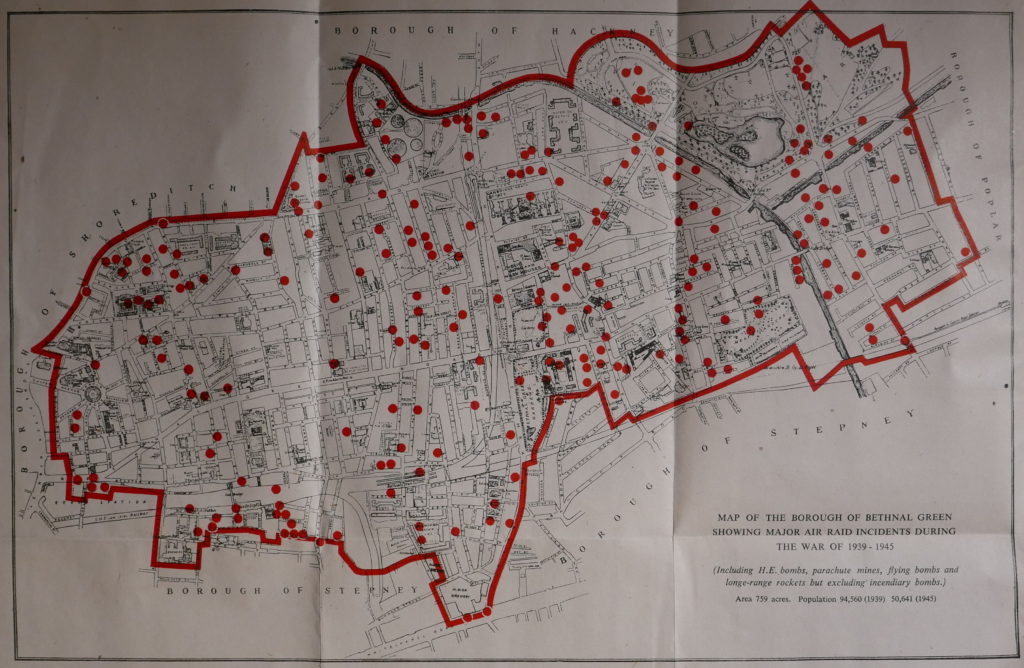

The booklet also includes a fold-out map showing the Borough of Bethnal Green with the location of major air raid incidents marked in red. Each dot represents a high explosive bomb, a parachute mine, flying bomb (V1) and long-range rocket (V2), but excludes incendiary bombs. (Click on the map to open a larger version)

Note in the bottom right hand corner the impact of the war on the population of Bethnal Green, with a population of 94,560 in 1939 falling almost by half to 50,641 in 1945.

Starting in 1938, we discover that 66,828 gas masks were issued to the residents of Bethnal Green on Wednesday and Thursday the 28th and 29th of September. This was followed by a period of comparative calm, until the war came to Bethnal Green with a vengance in August 1940:

“On Saturday night and in the early hours of Sunday morning, the 24th and 25th August 1940, the storm broke and we in Bethnal Green had some ideas of the dangers that lay ahead. Our baptism of fire consisted of several high explosive bombs each weighing 50 kilograms which were scattered over a fairly large area of the borough, extending almost in a line from The Queen Elizabeth Hospital in Hackney Road to Lessada Street, east of the Regent’s Canal in Roman Road.”

The raids continued through September between Saturday 7th September and the 24th of September 1940, when 95 high explosive bombs, two parachute mines and literally thousands of incendiary bombs fell on Bethnal Green.

“No part of the district escaped this terrible holocaust. Bethnal Green Hospital, The Queen Elizabeth Hospital, the Central Library, Columbia market, the Power Station in Bethnal Green Road, the Hadrian Estate, the Burnham Estate, the Vaughan Estate and the Bethnal Green Estate were all hit, whilst the parish church of St. Matthew’s and St. Paul’s Church in Gosset Street were totally destroyed. On that night too, Columbia Market, which contained a very large public shelter was the scene of a very distressing calamity when a 50 kilogram bomb, by a million to one chance, entered the shelter by means of a ventilating shaft and caused extensive casualties to those sheltering.”

Thirty eight people were killed by the bomb on the Columbia Market shelter.

The booklet provides details that help understand Bethnal Green at the time. For example, there were still a number of stables across the Borough, and one of these, the Great Eastern Stables in Hare Marsh was hit and several horses were trapped and needed to be put down.

The composition of road surfaces amplified the impact of incendiary bombs as many were still covered by wooden blocks: “On the night of December 11th 1940, more fires were gaining hold on Bethnal Green than ever before. The area at the west end of Bethnal Green Road was a sea of flames, the wooden blocks which surfaced the road themselves catching fire and burning through almost to the concrete underneath.”

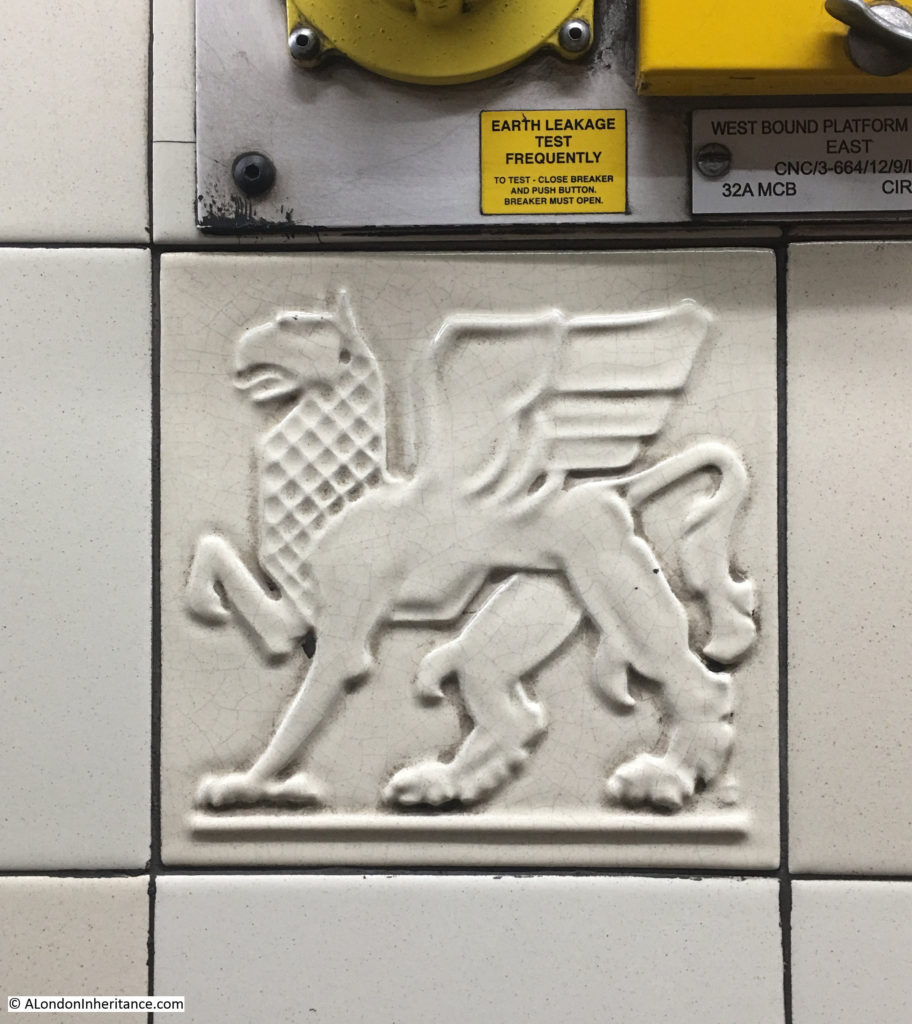

The booklet has a page covering the disaster at the Bethnal Green Underground Station. This was being used as a shelter and was one of the largest in London capable of accomodating 10,000 people.

The shelter was opened very rapidly in 1940 at the persistence of Herbert Morrison, the Minister of Home Security. The Sunday Mirror on the 6th October 1940 reported:

“The Man Who Gets Things Done – Herbert Morrison, new Minister of Home Security, beloved by Londoners, is the man who gets things done.

Standing on the platform of the uncompleted Bethnal Green Underground station, 65ft below ground yesterday, he asked L.P.T.B and local council officials why it was not being used as a shelter.

He was told there were certain technical difficulties. ‘Is there anything to stop the people using it right away?’ he queried brusquely. He was told there were not.

‘Then open it tonight’ said Herbert Morrison.

That is why several thousand men, women and children of the East End who last night found sanctuary in the station and tunnels – part of the new Tube extension not yet in use – bless the name of Britain’s ‘livest’ Cabinet Minister.

A.A. Shells were bursting in the sky during an alert when Mr Morrison and Admiral Sir Edward Evans arrived to inspect the station. Mr Morrison, after chatting with the experts, reached his decision about the opening of the station as a shelter in five minutes,

Council officials told him that everything was ready to make the shelter comfortable.

Someone said the pit in the concrete track should be boarded over. ‘Let them sleep on the track’ replied Morrison.

Mr Morrison said in an interview: ‘You can tell the people we are going to utilise every inch of shelter we can find and we’re going to do it quickly’

The booklet describes the Bethnal Green Underground shelter:

“It had a sheltering capacity of 10,000; the highest figure reached was 7,000 in 1940-1 and in the summer of 1944 during the flying bomb raids. The Tube played a great part in the life – at night and in times of danger – of a great number of people in Bethnal Green; particularly the old people and mothers with children. It was provided with a canteen, a sick bay with a trained nurse regularly in attendance, a visiting doctor, a concert hall capable of holding 300 people and a complete branch public library consisting of 4,000 volumes.”

The worst civilian disaster of the war happened at Bethnal Green Underground station on the 3rd March 1943. The booklet records:

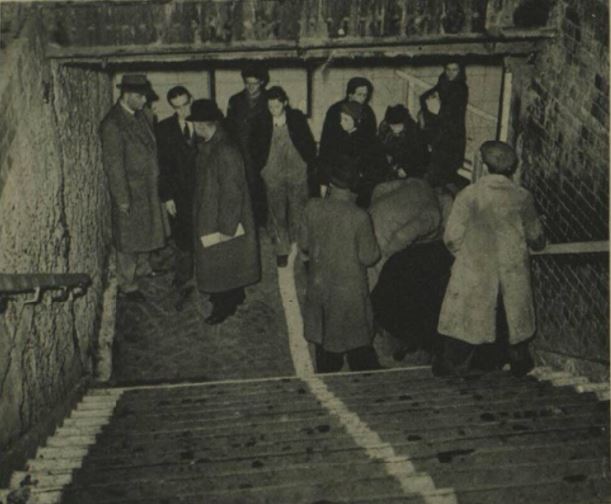

“On the night of the 3rd March the warning went at 8:17 p.m. and almost immediately hundreds of people were seen to be making for the shelter from all directions. It is estimated that in the first ten minutes after the sirens had sounded 1,500 people were admitted. Everything was normal and although the people were obviously anxious to get under cover there was no undue haste or panic, when suddenly, without any kind of preliminary warning, at 8.27 p.m. a salvo of rockets was discharged from a battery in Victoria Park. The shattering noise created by this operation undoubtedly caused the already anxious people to redouble their efforts to get into the shelter.

Unfortunately the reports of the guns were thought by many to be the sound of exploding bombs. At this critical moment it is said that a women, with a child, or a bundle, or perhaps both in her arms, fell on the stairs. So great was the pressure of the crowds behind her that in the matter of a few seconds there was a solid mass of bodies, piled up five or six deep, against which the people seeking admission and not knowing of the accident, still endeavoured to force an entrance.

On the instructions of the Home Secretary, Mr Herbert Morrison, a full enquiry into the circumstances of the accident was conducted by Mr. Laurence Rivers Dunne, M.C. one of the Magistrates of the Police courts of the Metropolis. The enquiry lasted from the 11th to the 17th March inclusive and in all eighty witnesses were examined. His final conclusions were:

(a) This disaster was caused by a number of people losing their self control at a particular unfortunate place and time.

(b) No forethought in the matter of structural design or practicable police supervision can be any real safeguard against the effects of a loss of self control by a crowd. The surest protection must always be that self control and practical common sense, the display of which has hitherto prevented the people of this country being the victims of countless similar disasters.”

The report appeared to put the blame on the people attempting to enter the shelter and their loss of control.

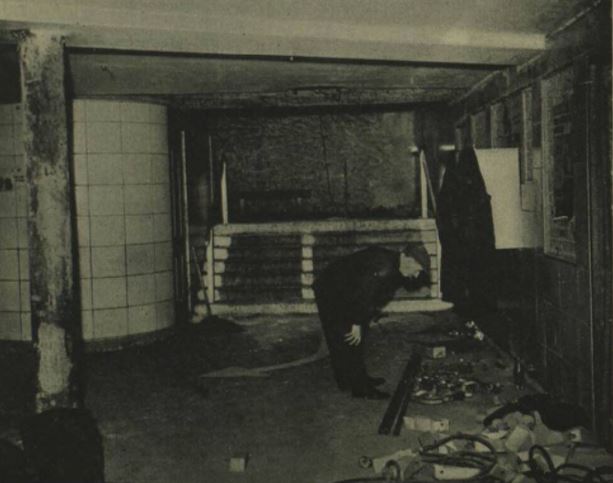

In reality, the entrance to the stairs down to the shelter were poorly lit, there was no central handrail and insufficient police or wardens to manage access to the shelter.

The Illustrated London News on the 13th March 1943 published an account of the tragedy and published photos of the entrance showing only side handrails and the general poor condition of the entrance.

It is easy to imagine how simple it would be for someone to stumble and fall in a crowd, and the impact that would have in such a confined entrance with no safety features.

The Illustrated London News report states that there were no bombs and no panic, and makes no mention of the salvo of rockets. An apparent contradiction to the report by Rivers Dunne, and despite the report stating that “No forethought in the matter of structural design ” could have avoided the tragedy, immediately after the tragedy, steps were taken to improve lighting, add handrails and barriers to shelter enhances, perhaps an acknowledgement of the contribution that the lack of these features had to the Bethnal Green tragedy.

173 people of all ages died on the 3rd March 1943 at the entrance to the Bethnal Green Underground shelter.

The entrance today – the woman fell at the bottom of the first flight of stairs:

A plaque recording the tragedy above the stairs:

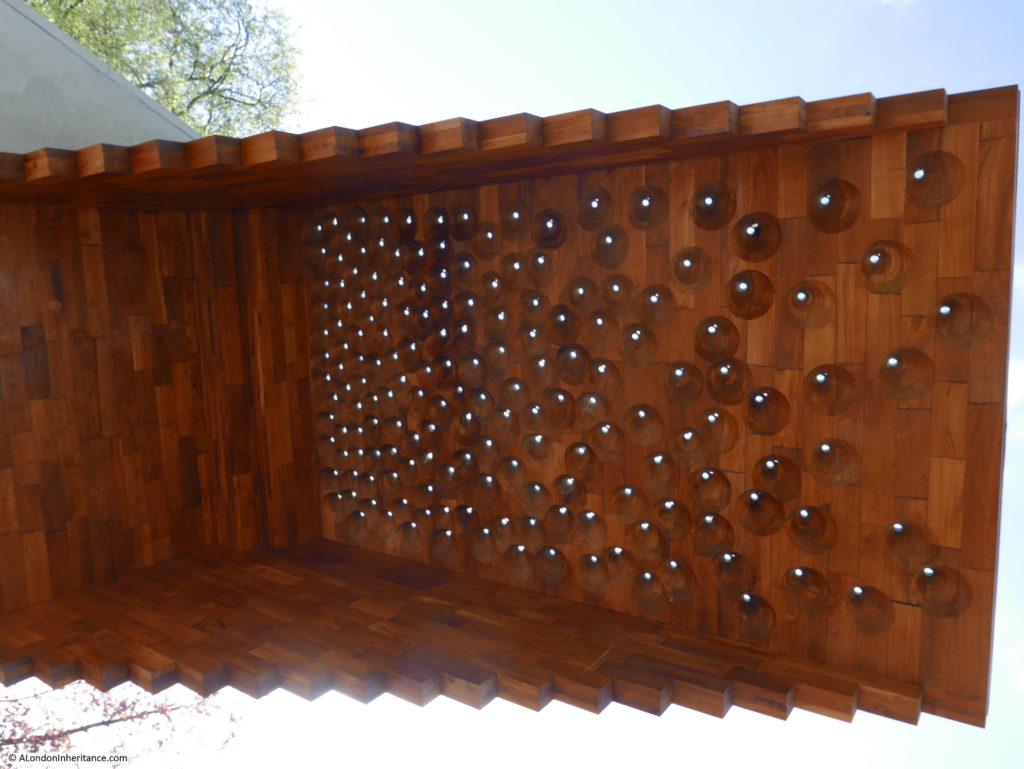

A memorial to the disaster was completed in December 2017:

The memorial is located by the entrance involved in the disaster and represents the stairs down from the street, with the names of those killed carved into the side of the memorial:

There are 173 small conical light shafts cut into the top of the memorial, and these are clustered closer together as the end wall is approached – representative of the way the tragedy unfolded:

The full names and age of those who perished are recorded on the upright support of the memorial. The repetition of the same surname, and the numbers of children involved shows the terrible impact that the tragedy must have had on individual family’s.

The memorial is a very fitting reminder of the tragedy at Bethnal Green Underground station in 1943.

One final comment on the tragedy comes again from the booklet and highlights the impact that war had on children:

“Some reference must be made to the work performed by the boys at the tragic Tube Shelter disaster. They helped with the injured and saw sights which probably no boy of such tender years has been called upon to experience. One boy was found by the Controller at the mortuary helping to unload the dead as they were brought from the scene of the disaster. The Controller said to him, ‘Don’t you feel somewhat upset by this?’ and the boy answered, ‘Well, Sir, I was sick when I first started, then I got over it, and anyway the job has got to be done.”

The remainder of 1943 and early 1944 was generally quiet in Bethnal Green, however Bethnal Green’s ordeal continued on the 13th June 1944 when a flying bomb fell in Grove Road. A total of twenty V1 flying bombs would fall on Bethnal Green.

These would be followed by the V2 rocket, with the first falling in Lessada Street in November 1944, the second in Parmiter Street in February 1945 and the final rocket just outside the borough boundary in Vallance Road in March 1945.

The booklet illustrates the effort needed by the Council and volunteers to respond to the bombing of Bethnal Green. The Borough Council had to arrange the clearance of 4,550 homes, providing storage space for the furniture from 1,350 and moving the furniture from 2,200 other homes to alternative accommodation.

Those too young to be conscripted into the armed forces were involved in a number of activities. Boys were used for multiple roles, acting as messengers, filling sand bags, installing blast walls at the London Chest Hospital, and it was the Scouts who erected the 5,000 bunks in the Bethnal Green Underground station shelter. Although evacuation of children from the city had started at the beginning of the war, the booklet records that a large number of children had drifted back to their homes and families in Bethnal Green. (This was also my father’s experience, as he only lasted three weeks after evacuation before returning home to the city).

The task of looking after and identification of so many dead civilians was a challenge for a single Borough. Of the 555 civilians killed during the war in Bethnal Green, there were 23 unidentified or unclaimed. These were buried in the communal grave at the City of London Cemetery, Manor Park.

Bethnal Green’s Ordeal also highlights the impact on the population of day to day precautions. For example, the black out came into full force on Friday 1st September 1939 and is recorded as being one of the war time restrictions that was the most difficult to bear. “It was easy to appreciate its importance during actual raids, but the hours of darkness were so many, especially during the long winter nights – many of which were raidless – that at times the depressing effects of the black-out were almost unbearable.”

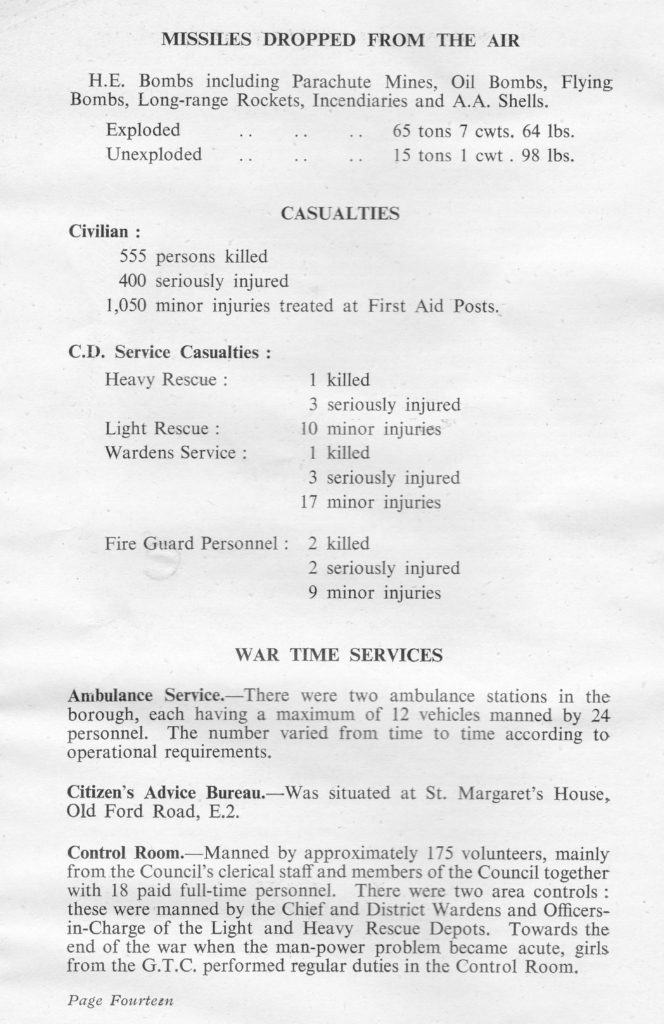

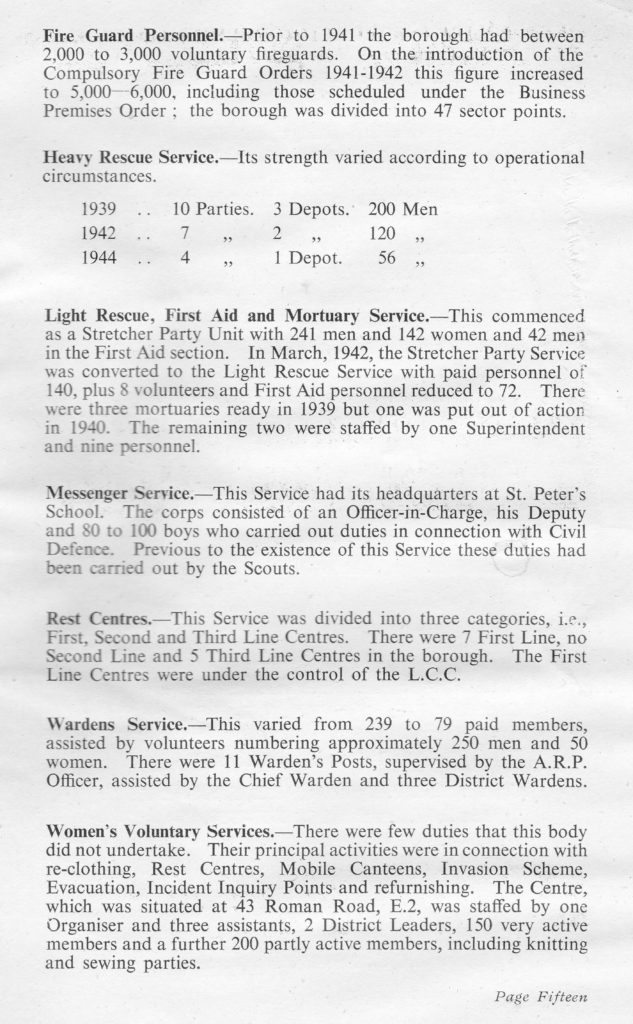

The booklet ends with two pages that provide some key statistics, and details of the organisations that developed within the borough to manage the impact of the war.

The memorial at the entrance to the Underground station is a reminder of the dreadful tragedy of one single event. The booklet is a reminder of the overall impact to one London Borough as summed up by the final paragraph in the booklet::

“Thus ends the story, perhaps rather fragmentary, of what an ordinary typical East End borough endured during the war years. It is hoped that it will serve as a reminder to the present generation and as a record for posterity of Bethnal Green’s Ordeal, 1939 – 1945.”