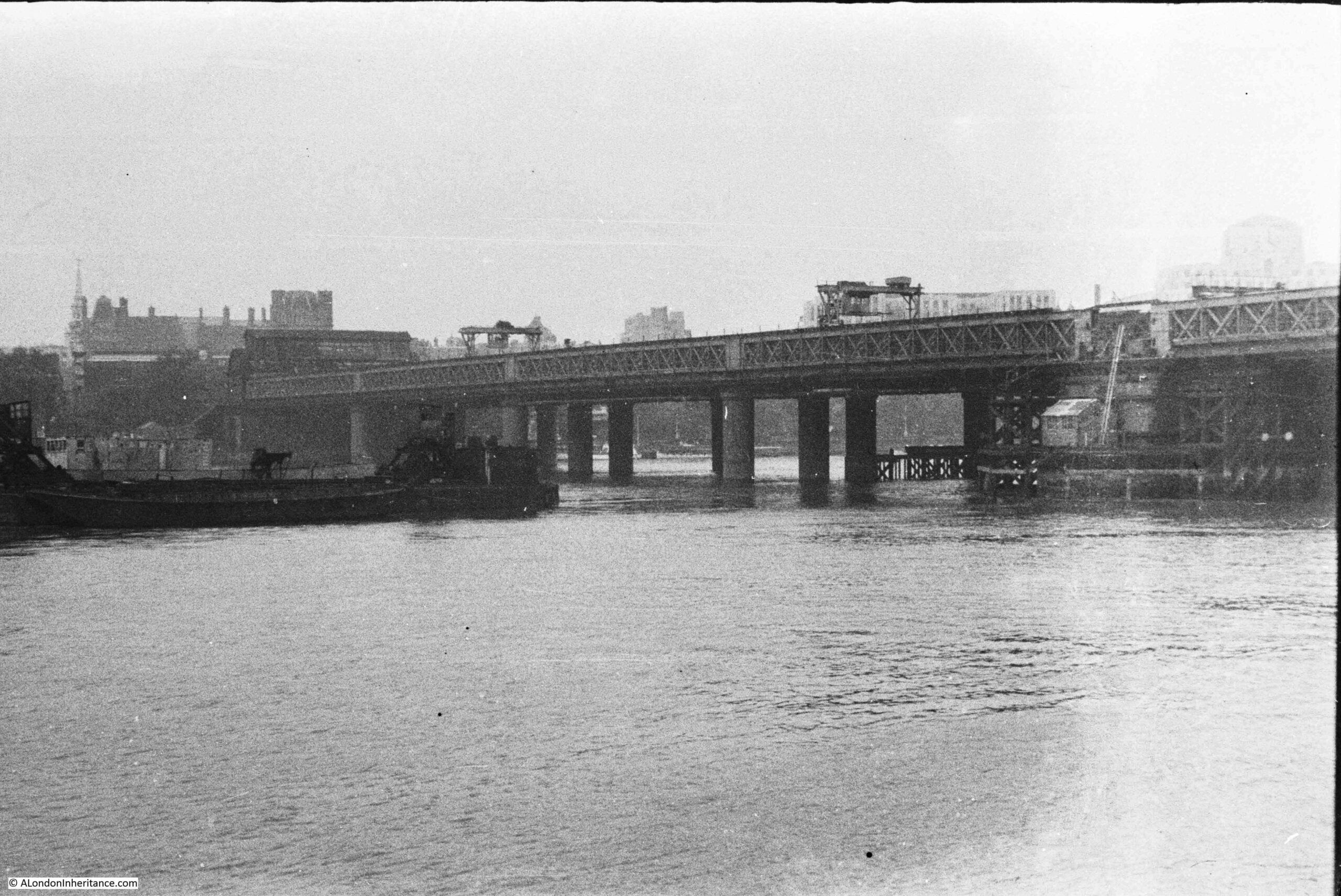

My father took the following photo of Hungerford Bridge from the south bank in 1947:

The same view in 2022:

The photos are seventy five years apart, and as could be expected the core of the bridge is much the same now as it was in 1947.

There are some minor differences. The brick structure above the pier on the right was missing in 1947, although its appearance today may suggest it is part of the original structure.

Two signal gantries can be seen above the tracks in 1947, and on the left of the bridge the entrance to Charing Cross Station can just be seen, where today, the 1991 office block, Embankment Place, above the station is the major feature at the end of the bridge.

The white structures along the length of the bridge in the 2022 photo support the Golden Jubilee Foot Bridge which was completed in 2002. There is a second foot bridge on the other side of the railway bridge, to an identical design.

These foot bridges replaced a single, narrow footbridge that originally ran along the far side of the bridge. It was not that pleasant a foot bridge, always had large pools of water across the walkway after rain, and was often not the route of choice after dark.

Hungerford Railway Bridge was opened in 1864. It was built by the Charing Cross Railway Company to provide a route into the new Charing Cross Station from across the river.

It was not the first bridge on the site, and investigating further reveals the source of the name, a failed market, the original bridge, and a very strange death.

Charing Cross Station was built on the site of the 17th century Hungerford Market, and the site had originally been home to Hungerford House, owned by Sir Edward Hungerford.

The Hungerford family name dates back to at least the 12th century with an early reference to one Everard de Hungerford. The family name came from the Berkshire town of Hungerford, and over the centuries, the family amassed a considerable amount of land and property and became very rich.

Many of the Hungerford’s had key roles in the governance of the country (in January 1377, Sir Thomas Hungerford was elected speaker of Parliament), and in national events (for example during the Civil War Sir Edward Hungerford was in command of the Parliamentary forces in Wiltshire, where it was reported that he carried out his responsibilities with an unpleasant zeal).

The first record of the Hungerford’s owning a house in the Strand was when Sir Walter Hungerford took up residence in 1422.

The Hungerford’s would own a house in the Strand until the late 17th century, when Sir Edward Hungerford (the nephew of the Civil War Hungerford of the same name) decided to try and create a market to rival the recently opened, nearby, Covent Garden Market.

An Act of Parliament in 1678 granted Sir Edward Hungerford permission to let some of the grounds occupied by Hungerford House for building leases and also to open a market on the site on Mondays, Wednesdays and Saturdays. The market opened in 1682.

Despite being in what seemed to be an ideal location, the market was not really a success. It was sold to Sir Christopher Wren and Sir Stephen Fox in 1685 and after their deaths, it was sold on to Henry Wise around the year 1717.

It would stay with Henry Wise and his descendants until 1830.

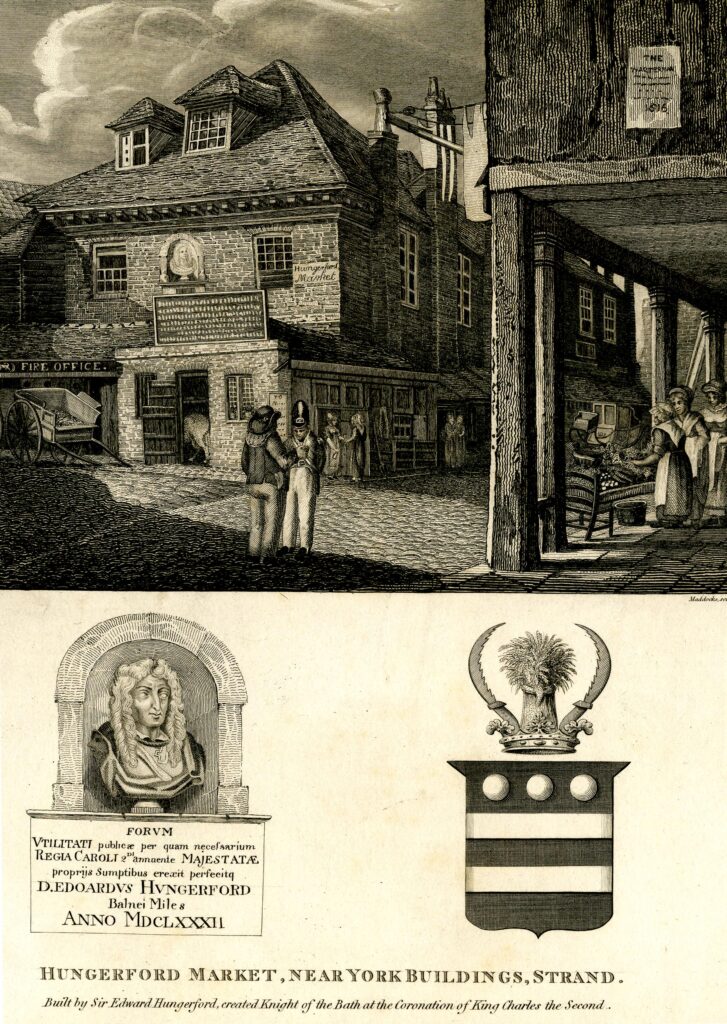

The following print from 1825 shows the original Hungerford Market:

The image at lower left shows the bust that is on the wall of the market building, and the text below names Edward Hungerford and confirms the opening date of 1682. The coat of arms on the right is that of the Hungerford family.

In the above drawing of the market, there is a sign on the building on the right about Watermen. The text below is too small to be readable. This is probably some reference to the stairs and access to the river at the far end of the market.

The following print from 1830 shows a busy market scene, with the River Thames visible in the gap between buildings in the distance.

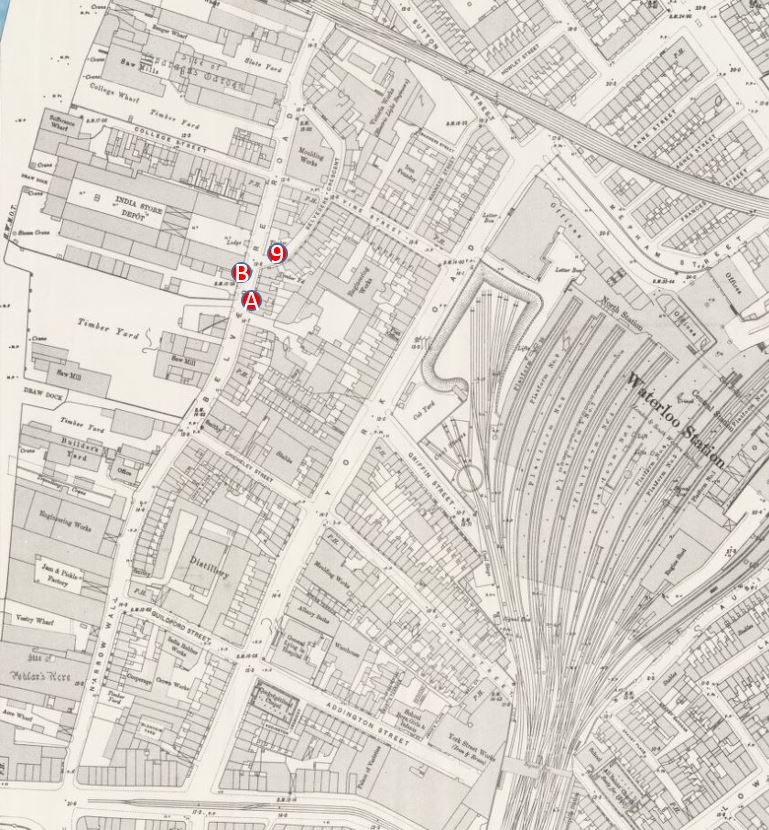

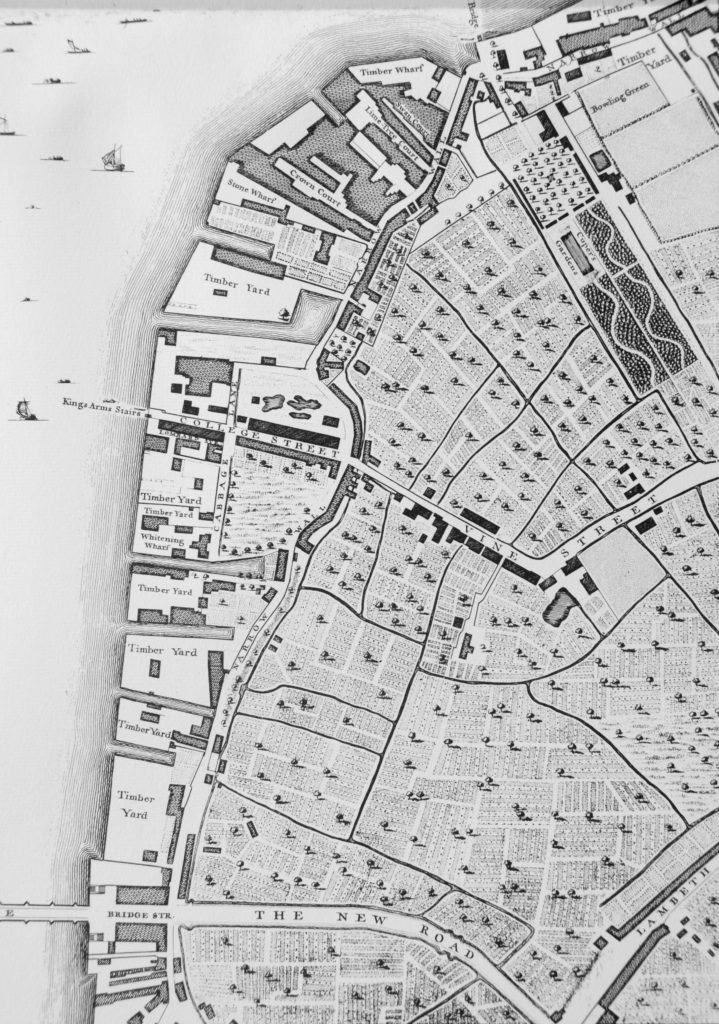

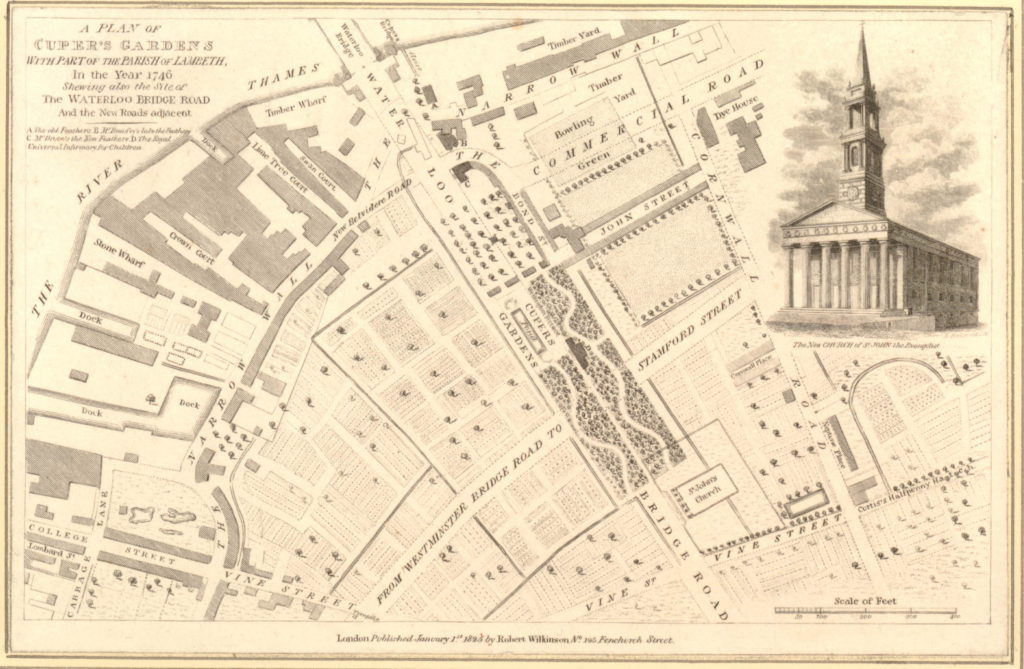

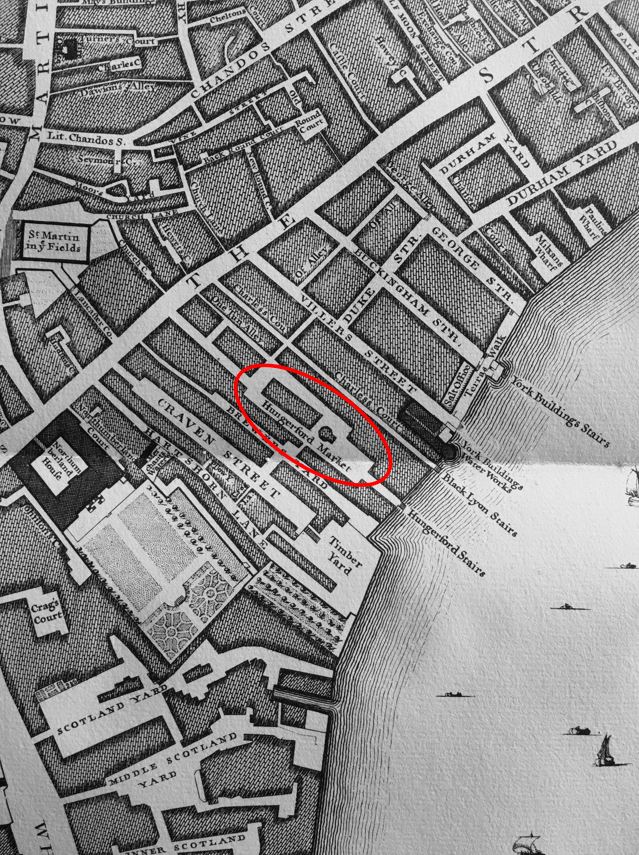

John Rocque’s map of 1746 shows the market between the Strand and the river, and shows Hungerford Stairs running down to the river:

As usual, to help with research, I checked newspapers for mentions of the old Hungerford Market. Papers of the 18th and 19th centuries record the numerous accidental and strange deaths that happened across London. I have read hundreds of these and one of the most unusual concerns a worker from Hungerford Market. This is a report from the Ipswich Journal on the 3rd of July, 1725:

“On Sunday Evening, an elderly Man that carried a Basket in Hungerford Market for his Livelihood, was drowned in an excessive Quantity of ‘Strip and go Naked’ alias ‘Strikefire’ alias ‘Gin’, at a notorious Brothel in the Strand; the poor miserable wretch expiring under too great a Dose of that stupefying Benediction.”

I have never heard of “Strip and go Naked” or “Strikefire” as a drink, and assume it was a form of Gin as this was the last alias.

It was with some trepidation that I put the name into Google, and the search results imply that it is now an American drink made out of beer, vodka and lemonade, also a cocktail made from beer, gin, vodka, lime juice, orange juice and grenadine.

Whatever it was in 1725, its description as a “stupefying Benediction” does sound rather appropriate.

18th century newspapers provide a view of the trades within Hungerford Market. These were in the paper for events such as bankruptcy so are not a complete list, but provide an indication: Wine Merchant, Butcher, Slaughter House, Oyster Merchant, Indigo Maker, Ironmonger, Coal Merchant.

As with any location which attracted people, there was also a public house – the Bull’s Head.

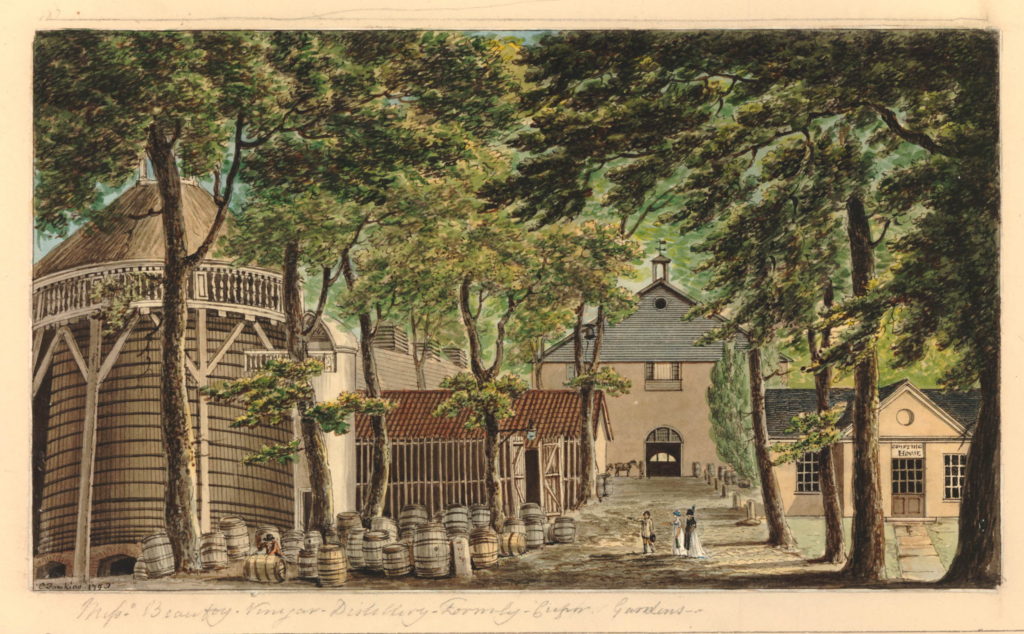

During the early decades of the 19th century, the market was becoming rather run down, dirty and surrounded by squalid housing.

The descendants of the Henry Wise, who had owned the building since 1717, sold the land and buildings to the Hungerford Market Company which had been formed in 1830.

The new company believed that by rebuilding, and providing a much improved market environment, the Hungerford Market could be just as big a success as Covent Garden and could also tempt some of the fish trade away from Billingsgate.

The new market buildings were much increased in size compared to the original market. New houses were built alongside, which included a number of pubs. The market buildings pushed the river embankment out by a further 150 feet and a set of stone stairs were constructed down to the river.

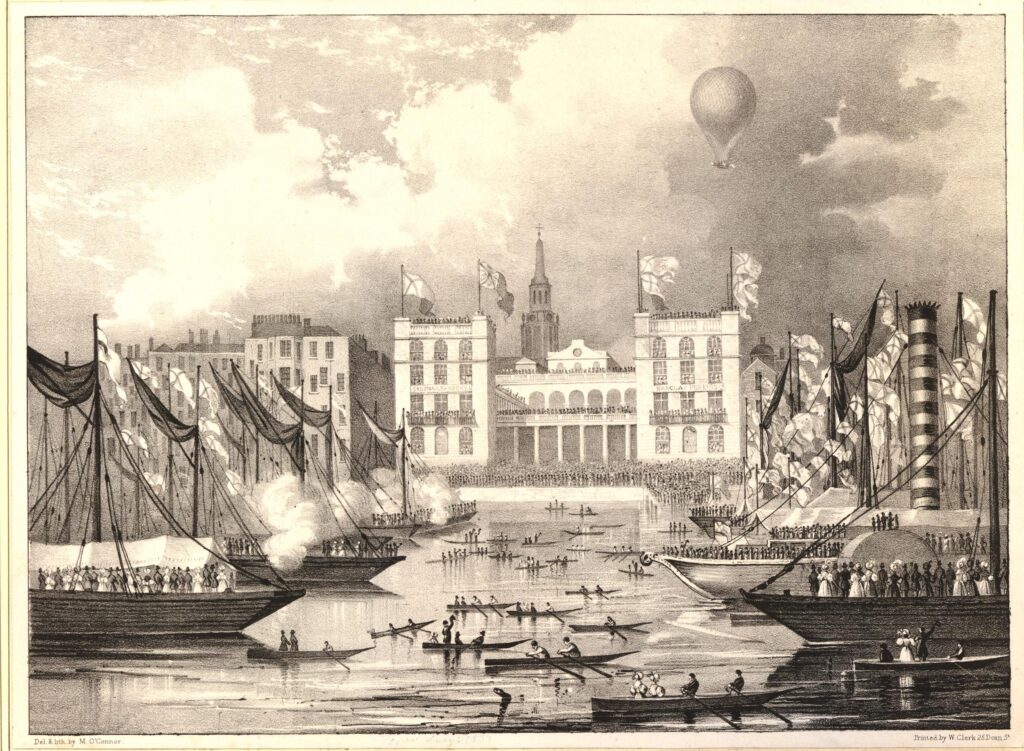

The following three prints of the opening ceremony on the 2nd of July, 1833, give an impression of the scale of the new market buildings and the grandeur of the opening, which was intended to give the market a considerable amount of publicity, and attract Londoners from as far afield as possible into the market.

The following print shows the view from the river, with crowds of people in front of the market and on boats on the river.

The opening of Hungerford Market was the place to be seen for the fashionable Londoner of 1833 as the following account from the Morning Advertiser on the 3rd of July, 1833 records:

“It having been announced that the opening of this splendid work was to take place yesterday at two o’clock in the afternoon, crowds began to assemble in the forenoon. By the specified hour, the concourse of people which thronged every part of the market, and all places adjoining, whence a view of what was going on could be had, was truly immense.

Of the numbers present it was impossible to form any conjecture which could be depended on. The large hall was most densely crowded with an assemblage of the most respectable kind, including much of the female beauty and fashion of this vast metropolis. The lower quadrangle was no less densely filled with an assemblage of the same class. The same may be said of the space appropriated to stalls and benches, underneath the colonnade. The quadrangle fronting the Strand, being open to all, was literally crammed with human beings. Indeed the open space in that particular part looked like a living mass of human beings.

The pavement on the south side of the magnificent building, which projects into the Thames, was so crowded with persons of all descriptions, that it was next to impossible to move from one part of it to another. The balconies at the top of the building, though a much higher price was demanded for admission to them, were filled with an assemblage of ladies and gentlemen. The view from these balconies was exceedingly interesting. It commanded an extensive prospect of the Surrey hills, and of a very considerable part of London, including a large portion of the Thames. Westminster and Waterloo Bridges were crowded with spectators, as were the tops of a great many houses in the neighbourhood of Hungerford-market.

The river was a most interesting scene; it was covered with boats, all as full as a regard to safety could justify. The coal barges in the neighbourhood of the market were so numerous and so close and so well filled that one could scarcely persuade himself they floated on water.

Taken altogether, we should say, it is very seldom indeed that so many human beings are congregated together.”

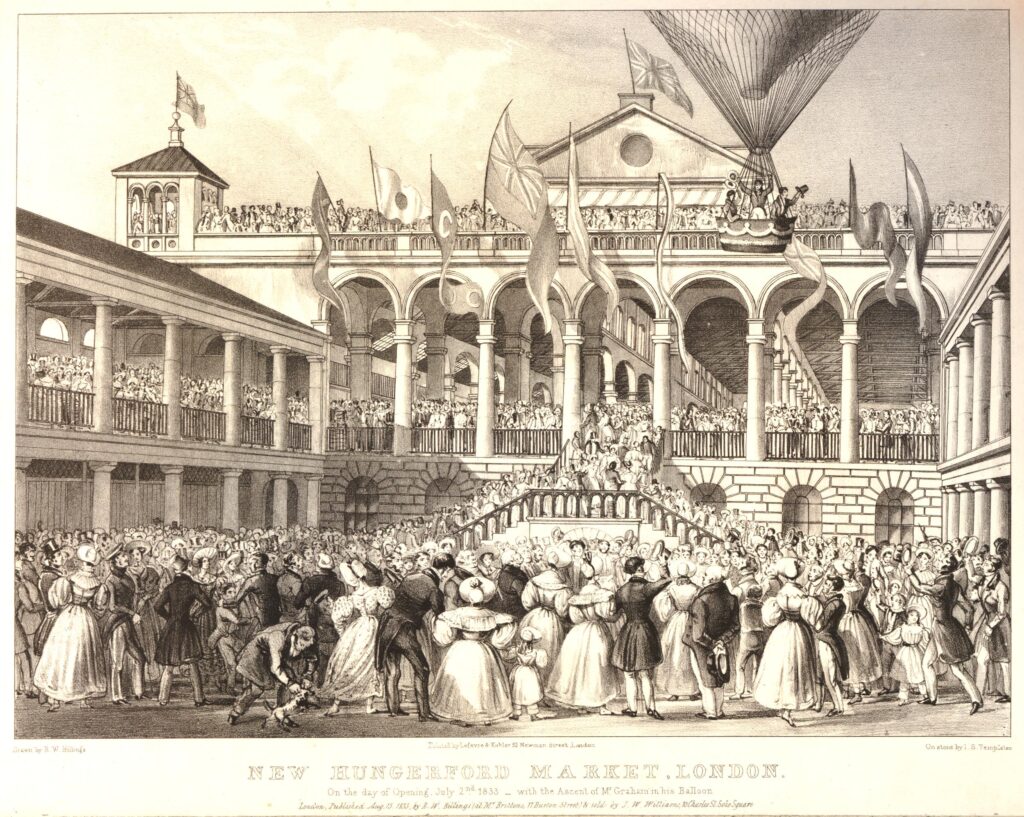

The following print shows the main attraction during the opening of Hungerford Market, a balloon ascent:

And the following print shows the balloon taking of from the quadrangle of Hungerford Market.

The balloon was piloted by George Graham, a prolific 19th century balloonist, who took two passengers with him in the basket.

The balloon took of at 4:30 in the afternoon. It went straight up for about sixty feet before heading in a south-easterly direction. Those in the basket waved their hats to cheers from the crowd as the balloon gained height.

By the time it had been up for 20 minutes it was described as being as small as a kite and after 30 minutes it was all but invisible, as it headed in the direction of Gravesend.

George Graham undertook many flights during the first half of the 19th century, and his wife was also a balloonist.

Margaret Graham was the first British woman to undertake a solo balloon flight, when in 1826 she took off from White Conduit Gardens in Islington, the location of her first flight with her husband just a couple of years before.

Individually, the couple would have a number of accidents. In one flight in 1838 George’s balloon hit a chimney on take off causing bricks to fall on an onlooker who died as a result. In a flight with his wife in 1851, the basket hit a rooftop just after launch causing him to fall from the basket and sustaining serious injuries.

In 1836, Margaret sustained serious injuries when during landing, her passenger stepped too early from the basket causing the balloon to rise, and Margaret to fall from a height.

In 1850 she suffered serious burns when a balloon caught fire.

George and Margaret had three daughters and the couple got them involved with ballooning. In 1850 Margaret flew with her three daughters causing something of a public outcry for taking all her children with her on what was considered a dangerous activity.

Despite having taken part in very many balloon flights Margaret died peacefully in her bed in 1880 at the age of 76.

Back to the opening of Hungerford Market, and in the evening there were fireworks and a ball was held which was “numerously and fashionably attended, and was kept up till a late hour with great spirit”.

The market buildings cost around £100,000 to build, and were expected to be a considerable success and rival Covent Garden and Billingsgate. At opening, all the market space had been rented out.

In the main hall, shops on the eastern side sold fruit and vegetables, butchers, selling meat, poultry and animal food took shops on the western side. There were large cellars and store rooms beneath the building and space for a large number of fish mongers. Space was provided for small traders with benches and stalls.

To try and tempt customers to the market, steam boats were run from east and west London along the Thames to the river stairs at the market. The market had one final trick to tempt what they called “the housewives of Lambeth and Southwark” to the market, and that was a bridge.

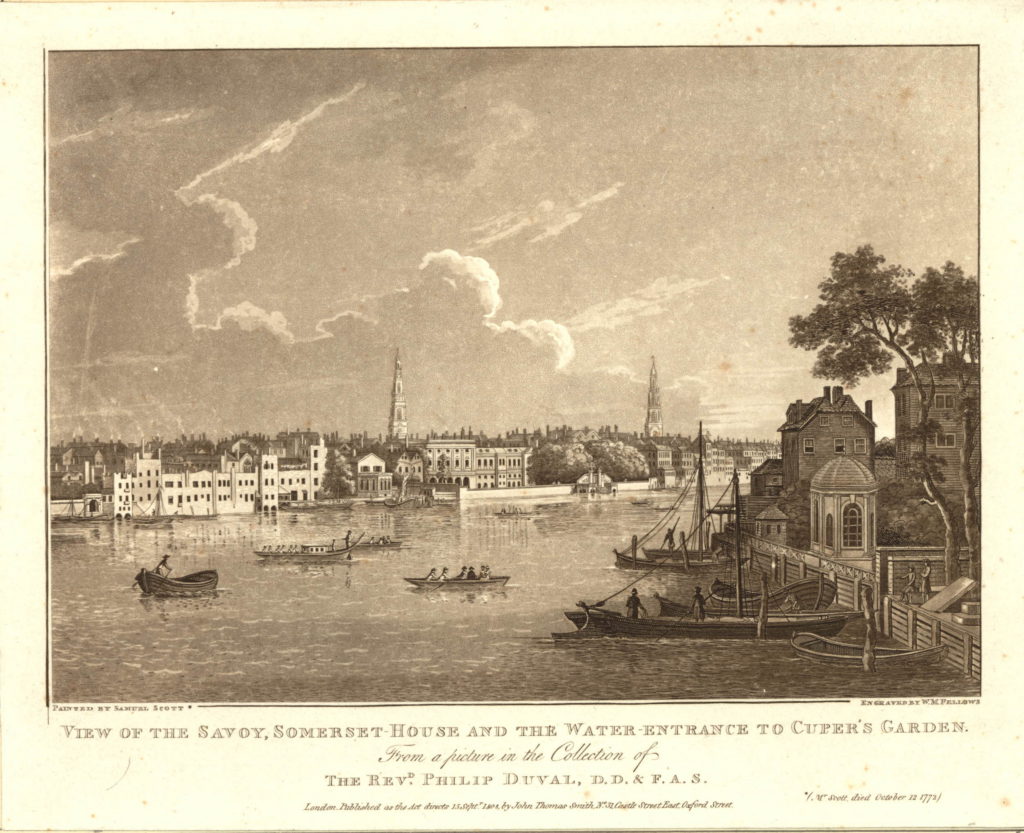

The above and below prints show the Hungerford Suspension Bridge which was opened to provide direct access to the market from the south bank of the river, and to provide another route over the river, as compared to cities such as Paris, London was believed to have too few bridges.

The bridge was designed by Sir Isambard K. Brunel and consisted of four individual chains running the length of the bridge, with two brick piers providing support for the chains.

The bridge was a considerable financial success. In their 1845 report for the first year of operation, the Directors recorded that tolls to cross the bridge raised £9,000 in a year. When the bridge was built it was expected that the daily traffic would be about 8,000 people, however after opening the bridge was attracting nearly 14,000 people.

The success of the bridge was such that the Board decided to pay the Directors £500 for their services to the company.

In a sign of what was to come, at the Board meeting in 1845, the Directors agreed to lease the bridge to the Central Terminus Rail Company for a fee of £186,000.

In the 1830s / 1840s, the area around Hungerford and Waterloo Bridges was being seen as a location for a railway terminus that would service the south east and south of the country, and connect into London Bridge – a subject way out of the scope of today’s post.

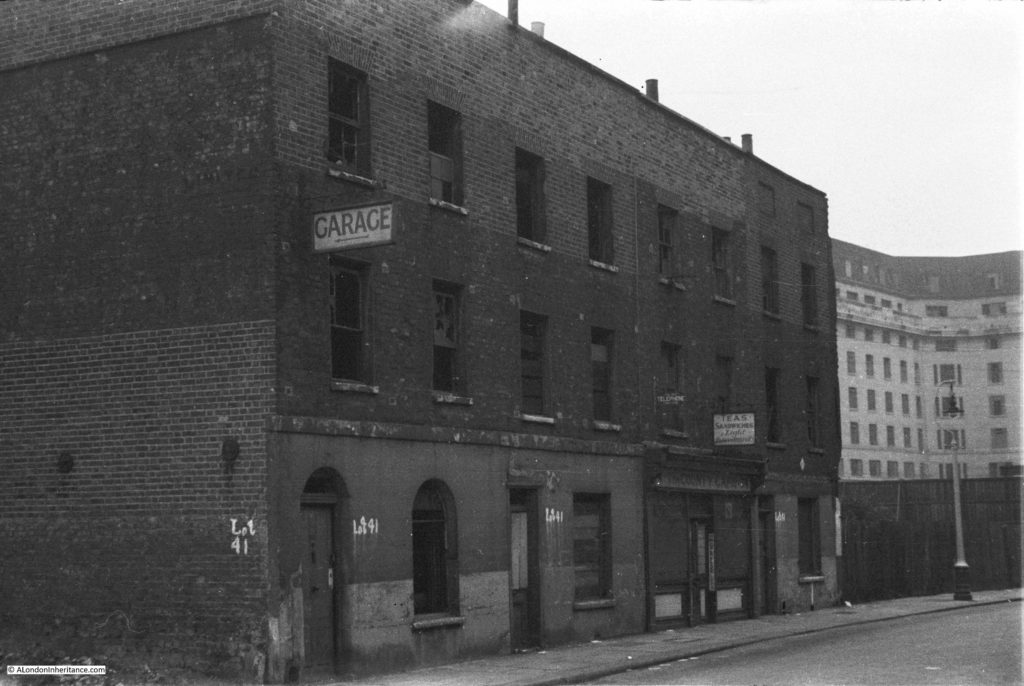

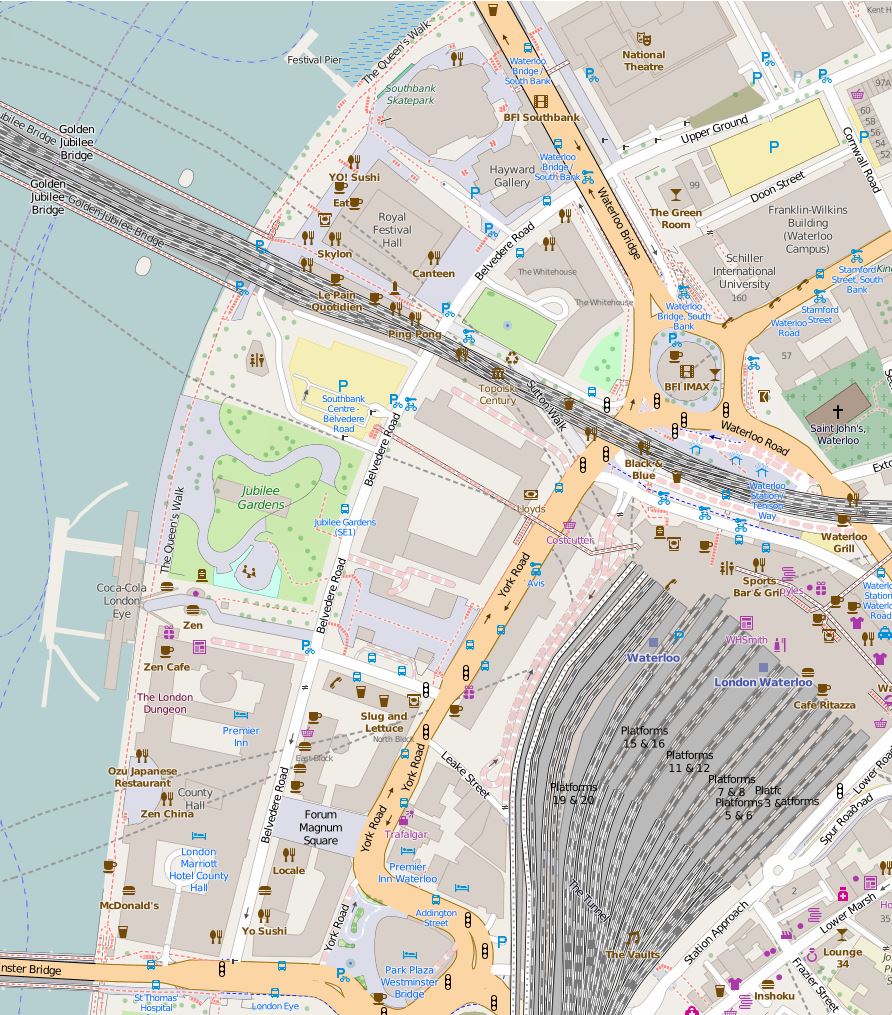

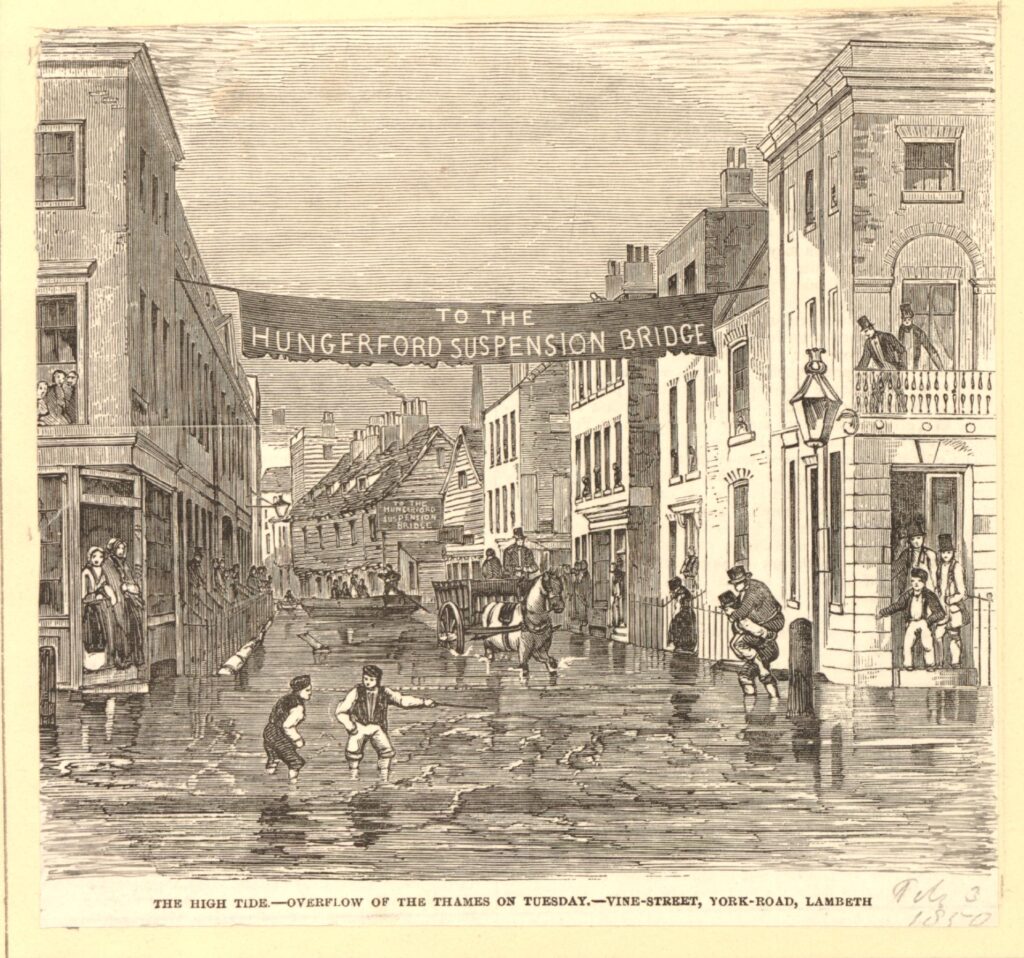

An interesting print from 1850 about flooding caused by a high tide shows some of the advertising for the Hungerford Bridge. The following print shows flooding in Vine Street which once ran where the Shell Centre building now stands on the South Bank, up to York Road. A large banner across the street directs people to the bridge, with another sign on the side of the terrace of houses towards the end of the street on the right:

The south bank, being part of low lying Lambeth Marsh was subject to frequent flooding at high tides as shown in the print.

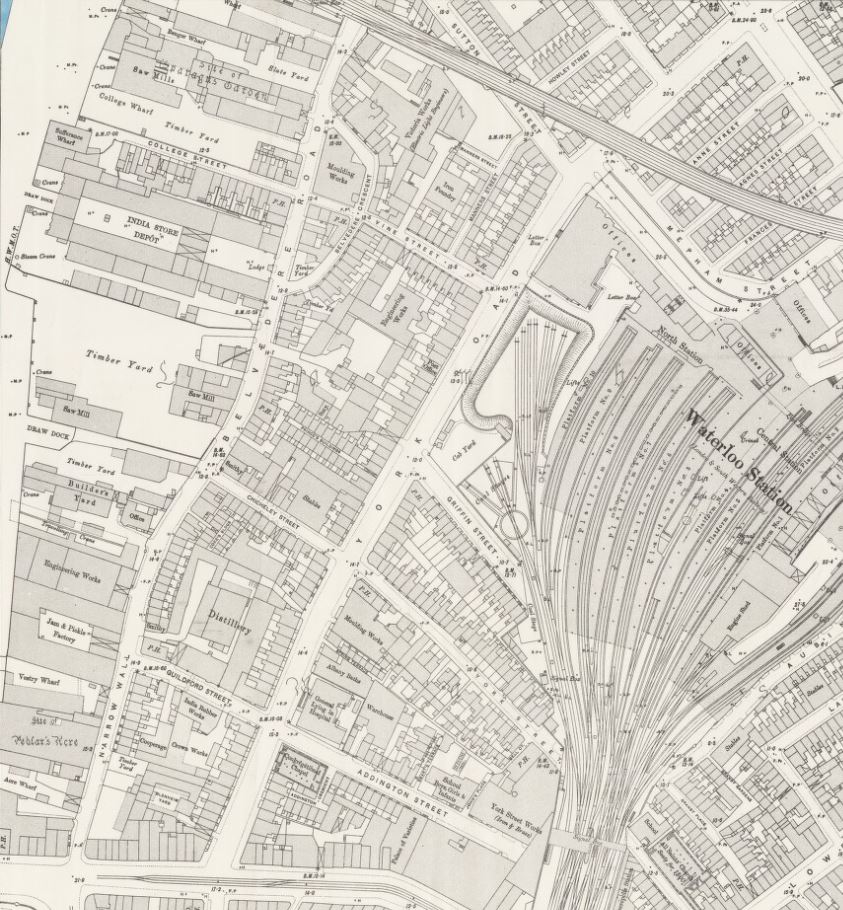

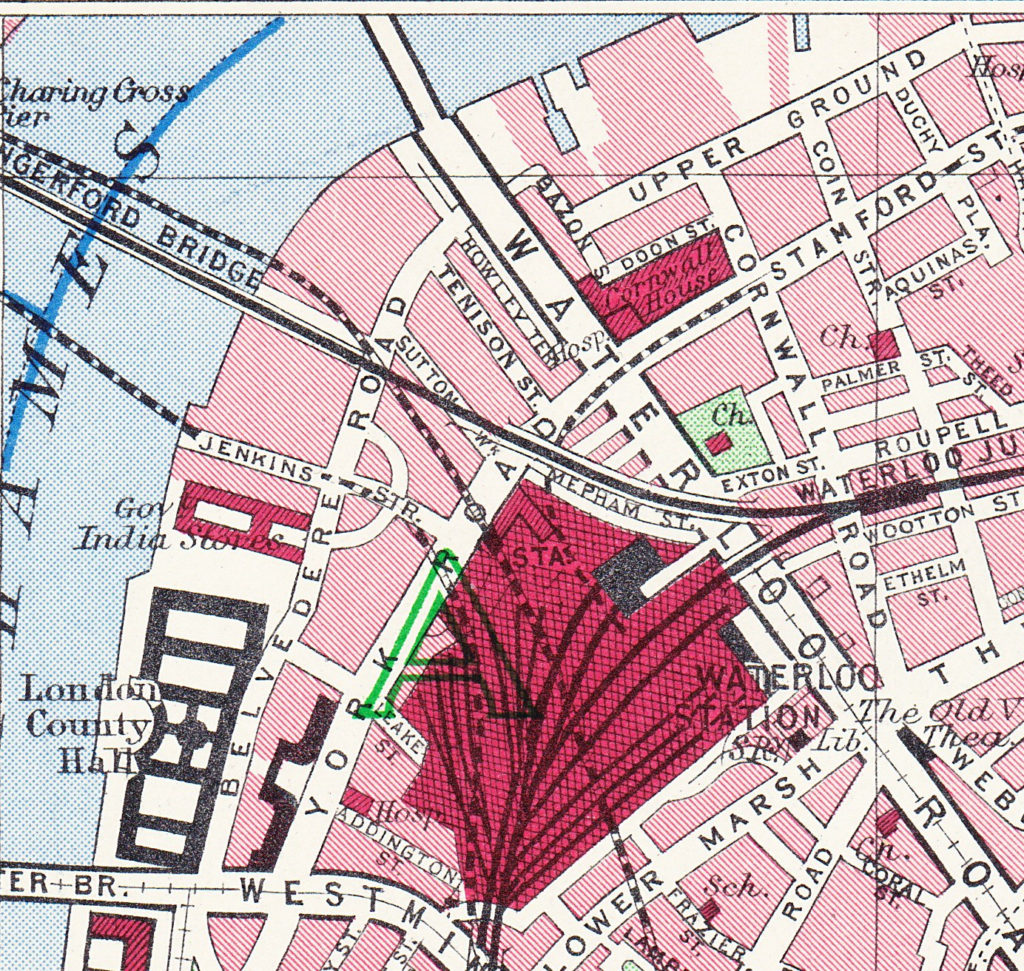

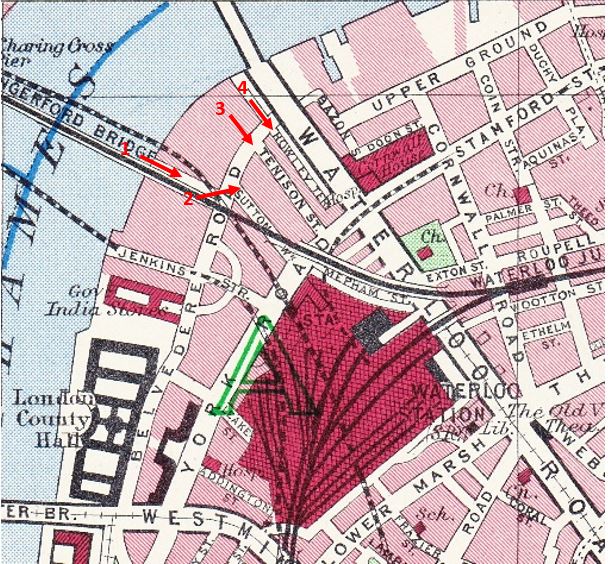

In the following extract from the 1894 Ordnance Survey map, I have ringed the location of Vine Street (‘Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland“):

Despite the optimistic opening, steam boats bringing customers from along the river and the bridge to tempt customers from south London, the market was not a success.

In 1851 a Hungerford Hall was built on part of the site for lectures and exhibitions, however this building burnt down during an accident when lighting gas lamps. The fire also caused damage to the main market hall.

The market would close by the end of the 1850s.

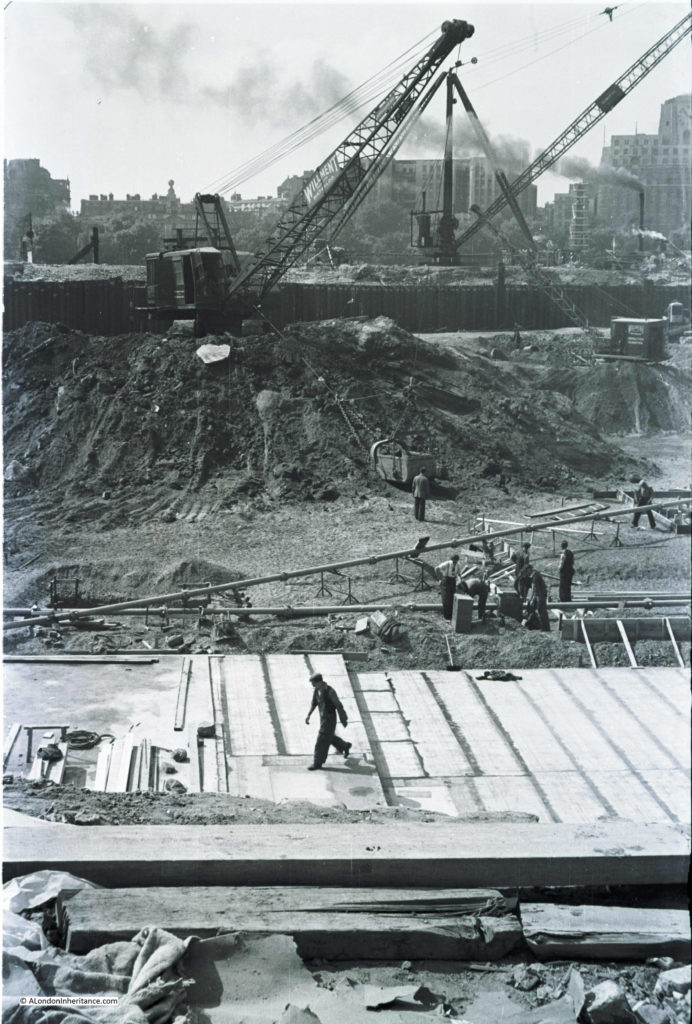

Plans for new railways and stations had been developing during the mid 19th century, and the entire site of the market was purchased by the Charing Cross Railway Company in order to construct Charing Cross Station.

The station would serve as a terminus of a route from the south of the river, therefore a new bridge was needed, and this resulted in the demolition of the original Hungerford Bridge. The railway bridge was approved by the 1859 Charing Cross Railway Act, and construction of the new bridge started in 1860.

Charing Cross Station (and therefore the bridge) opened on the 11th January 1864, and quickly became a busy rail route between south and north sides of the river.

Demolition of the bridge was not the end for parts of the original suspension bridge.

One of Brunel’s projects had been the Clifton Suspension Bridge. This had run into delays and financial problems and Sir John Hawkshaw and William Henry Barlow took over construction of the bridge as consultant engineers, working to complete the bridge.

They were aware of the demolition of the Hungerford Bridge, and to help with the financial difficulties in completing the Clifton Suspension Bridge, they purchased the chains and ironwork from the original Hungerford Bridge for £5,000.

Many of these chains still remain, and look out on a very different view than when they spanned the River Thames (see my post on the Clifton Suspension Bridge and my visit to the hidden chambers beneath the bridge in this post):

As well as some of the chains still being in use, the core of the piers from the first bridge were used in the construction of the piers for the new railway bridge.

The new Hungerford Railway Bridge initially provided a route for pedestrians across the river, with two footpaths on either side of the bridge. A toll of a half penny was charged up to 1878.

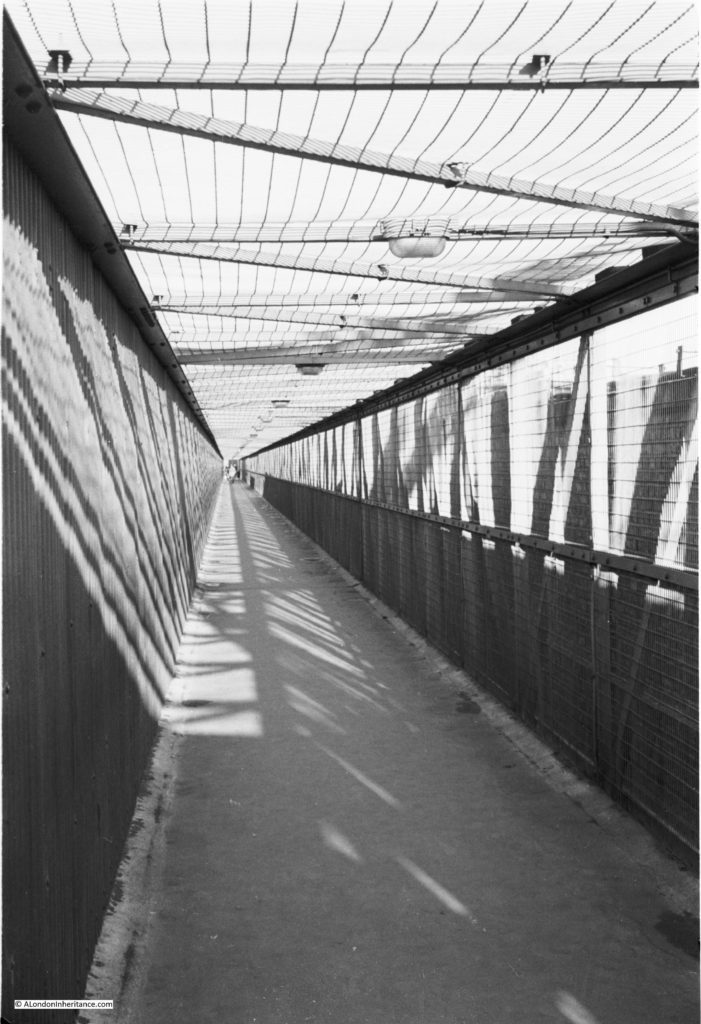

Initially the bridge provided four tracks across the river, however this was later widened to six tracks by the removal of the pedestrian routes, which were moved to a pedestrian way along the outside of the bridge.

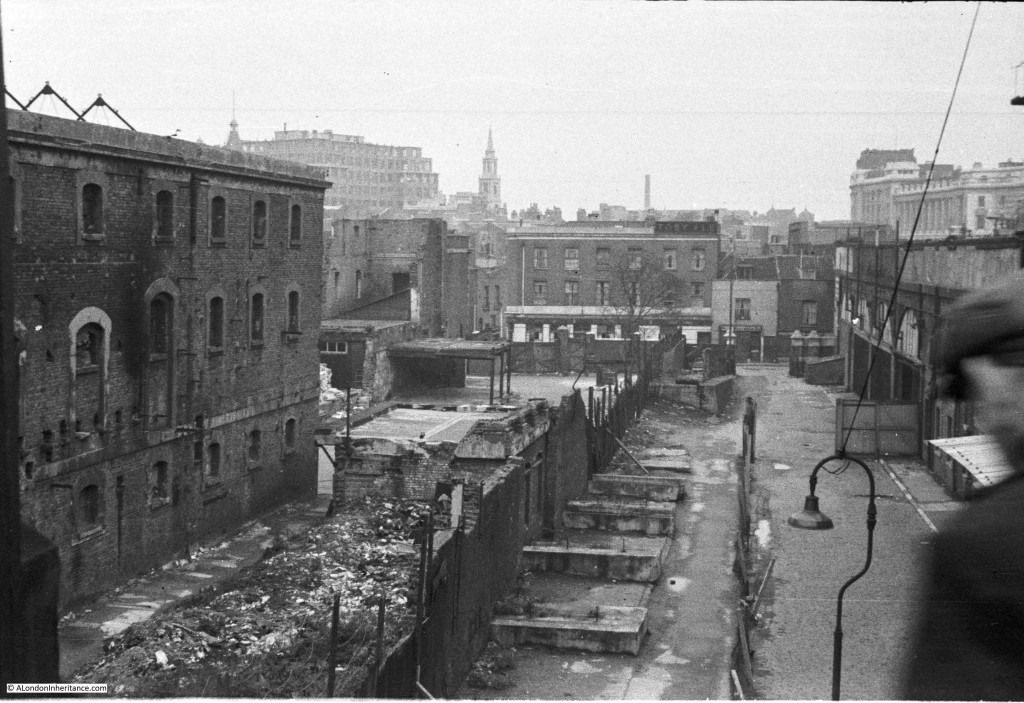

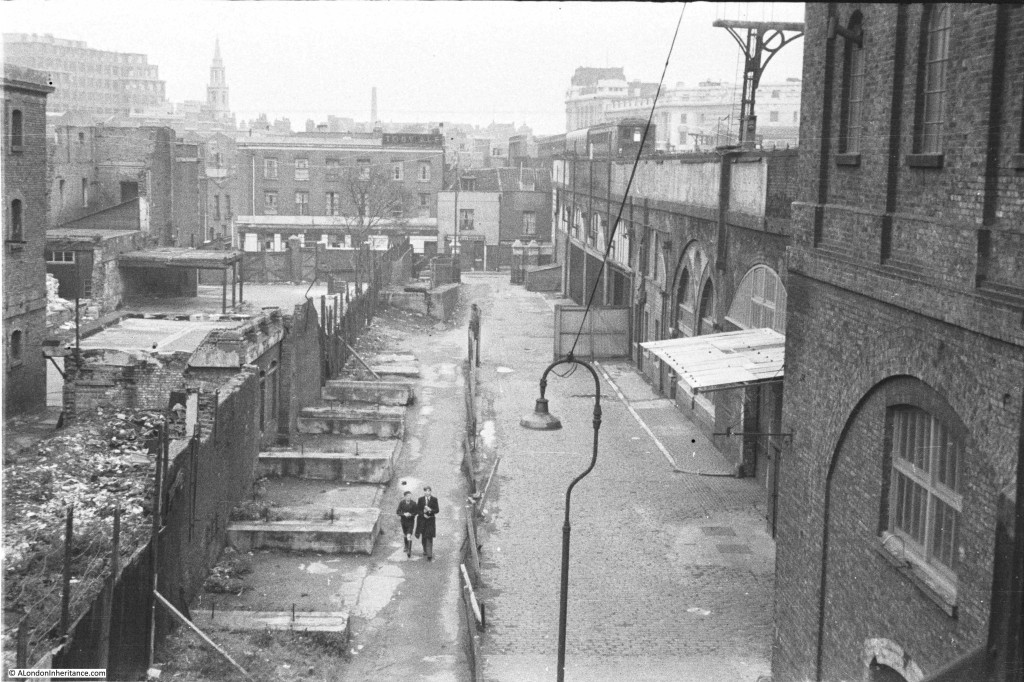

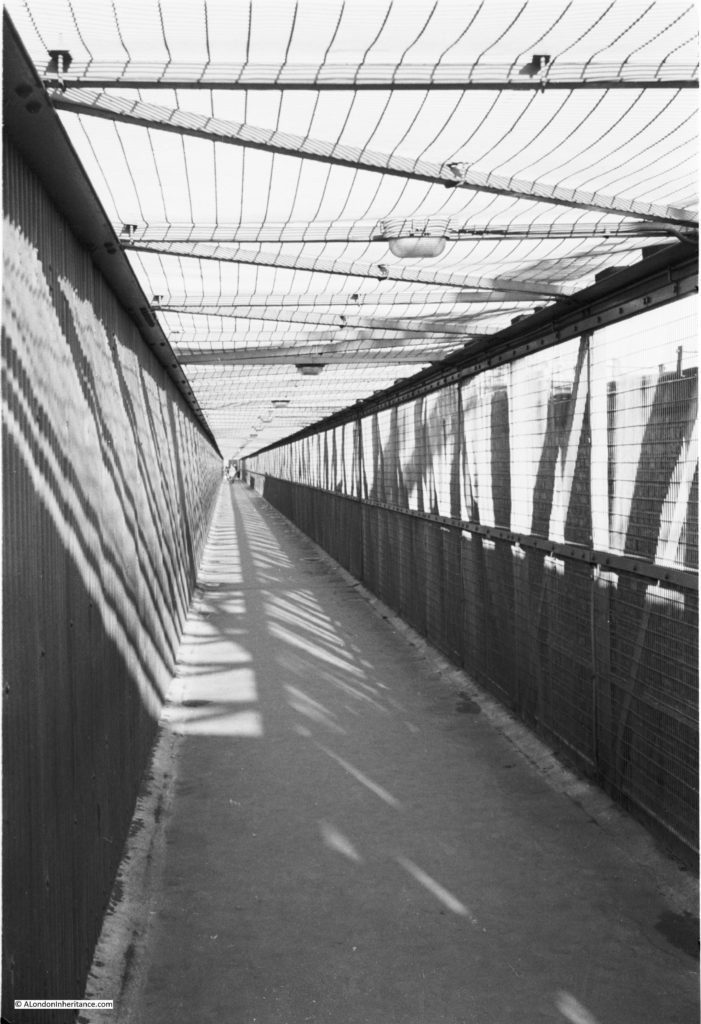

The pedestrian route alongside the bridge as it appeared in the early 1950s:

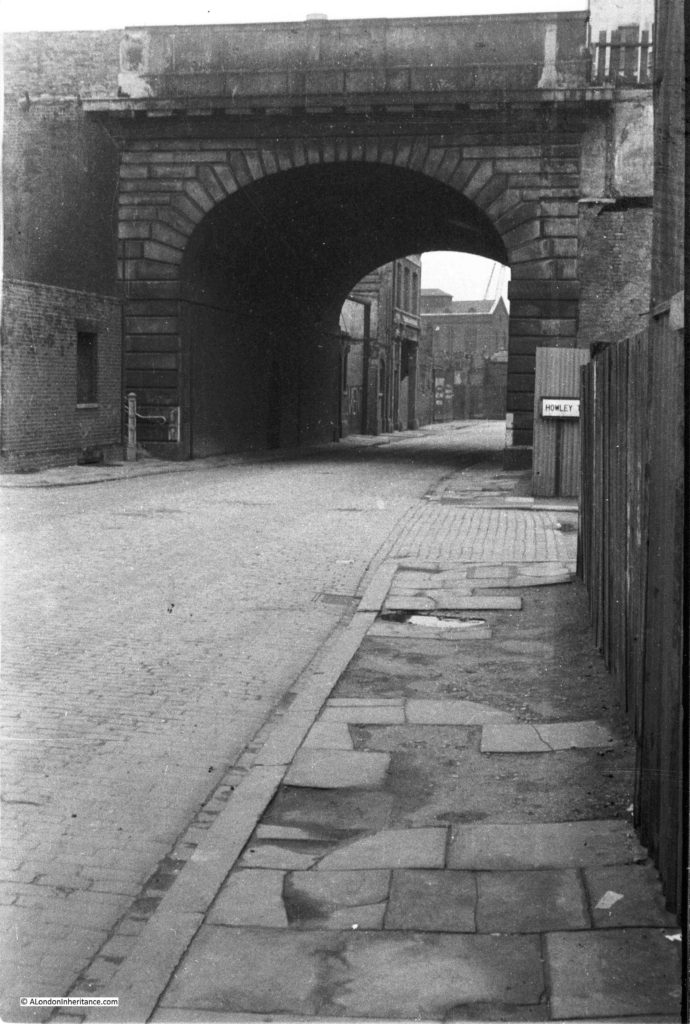

The entrance to Charing Cross Station as it appears today:

The ornate construction in the forecourt is a reconstruction (not a replica) of the Eleanor Cross that was located nearby and destroyed in 1647. The original Eleanor Cross was one of several built across the country in the late 13th century to mark the route when the body of Queen Eleanor was carried from Nottinghamshire for burial in Westminster Abbey.

Although the main market buildings were very slightly further back from the front of the above building, they were built on the site of part of the building, the station concourse and the platforms down to roughly where Villiers Street is today, with the steps extending down into the river. The later construction of the Embankment pushed further into the river

The following postcard shows Charing Cross Station as it appeared at the turn of the 19th / 20th century when the main building served the planned purpose of a hotel. Designed by Edward Middleton Barry in the French Renaissance style and which became one of the most fashionable hotels in London. Barry also designed the cross in the station forecourt:

Plans for the reconstruction of London after the war proposed demolishing bridges such as Hungerford Bridge and routing rail traffic in tunnels, however there was no way in which this could be financially justified and the plans did not progress further than a paper proposal.

Hungerford Bridge now stands as a reminder of a centuries old family name, who had a house off the Strand in the 15th century, a site which became a market and is now occupied by Charing Cross Station.

All prints in this post are from the British Museum collection and reproduced under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) license.