There have been numerous studies over the years looking into how London should develop and that detail a vision and proposals for the future that are frequently very different to the past. Many of these proposals get no further than the written page, however it is fascinating to see how London could have developed into a very different city if some of these proposals had been implemented.

In the early 1970s, East London and the London Docklands were suffering from the closure of the docks, loss of industry and employment and the gradual exodus of people. The area had also never fully recovered from the significant damage of wartime bombing.

My posts on the 1973 Architects Journal issue covering East London have explored some of the original issues, and these can also be found in a strategic plan published in 1976 by the Docklands Joint Committee.

I found the 1976 publication documenting the strategic plan in a second-hand bookshop, having been originally from the Planning Resources Centre of Oxford Brookes University.

The front cover provides an indication of the type of change proposed for the London Docklands, from derelict docks and industrial buildings to housing and schools more likely to be found in the suburbs, rather than East London.

The 1970s were a decade of confusion in the development of the London Docklands.

Dock closure had started in 1967 and continued through to 1970 with the closure of the East India, St. Katherine’s, Surrey and London Docks. Although the West India and Millwall Docks would not close until the end of the decade, the future of these historic docks was clear due to their inability to support the rapidly increasing containerisation of goods passing through the docks. Development of docks at Tilbury, Southampton and Felixstowe were the future.

The area covered by the docks, the industries clustered around the docks, and the housing of those who lived and worked in East London was significant, running from Tower Bridge to Beckton where the River Roding entered the Thames.

The Conservative Secretary of State, Peter Walker was clear in his views that the task of development was outside the scope of local government, and as a result a firm of consultants, Travers Morgan were hired to investigate the possibilities for a comprehensive redevelopment of the area.

The proposals put forward by Travers Morgan in their 1973 report proposed a number of possible development scenarios which included office development, housing and even a water park, however their proposals had minimal input from those who still lived and worked in the London Docklands. The Travers Morgan report was opposed by the Trades Unions and local Labour authorities and the Joint Docklands Action Group was setup to coordinate opposition.

Labour took control of the Greater London Council (GLC) in 1973, and in the 1974 General Election, Labour formed a minority government. The Travers Morgan proposals were abandoned.

The Secretary of State for the Environment established the Docklands Joint Committee in January 1974. The objectives of the committee are summarised in the opening paragraph of their report:

“The overall objective of the strategy is: To use the opportunity provided by large areas of London’s Dockland becoming available for development to redress the housing, social, environmental, employment/economic and communications deficiencies of the Docklands area and the parent boroughs and thereby to provide the freedom for similar improvements throughout East and Inner London.”

The committee was comprised of representatives from the GLC and the London boroughs both north and south of the river that came within the overall boundaries of the docks (Newham, Tower Hamlets, Southwark, Greenwich and Lewisham). The Government also appointed representatives to the committee and community organisations were represented through the Docklands Forum who had two members on the committee.

The proposals produced by the Docklands Joint Committee were very different to those of the earlier Travers Morgan study. Travers Morgan had identified a future need for office space, along with housing and retail, however the proposals of the Docklands Joint Committee focused on what the existing inhabitants required and how their skills could best be used and therefore developed a future based on manufacturing and industry.

Another difference to the earlier Travis Morgan study was in the way that the Docklands Joint Committee aimed to involve and consult the local population of the docklands. Public meetings were arranged, a mobile exhibition of the proposals toured the area, and in the words of the preface to the proposals “every effort will be made to ensure that everyone affected has the chance to know what is being proposed, and why, and to make his or her views known.”

The Strategic Plan as a draft for public consultation was published in March 1976 with a request that comments should be sent by the 30th June 1976.

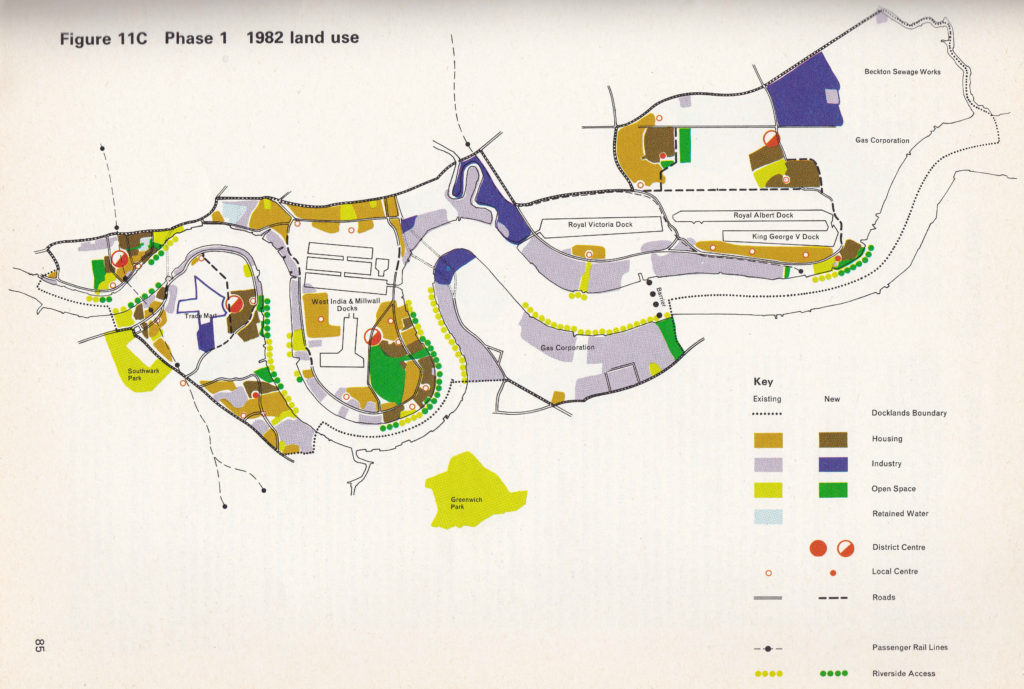

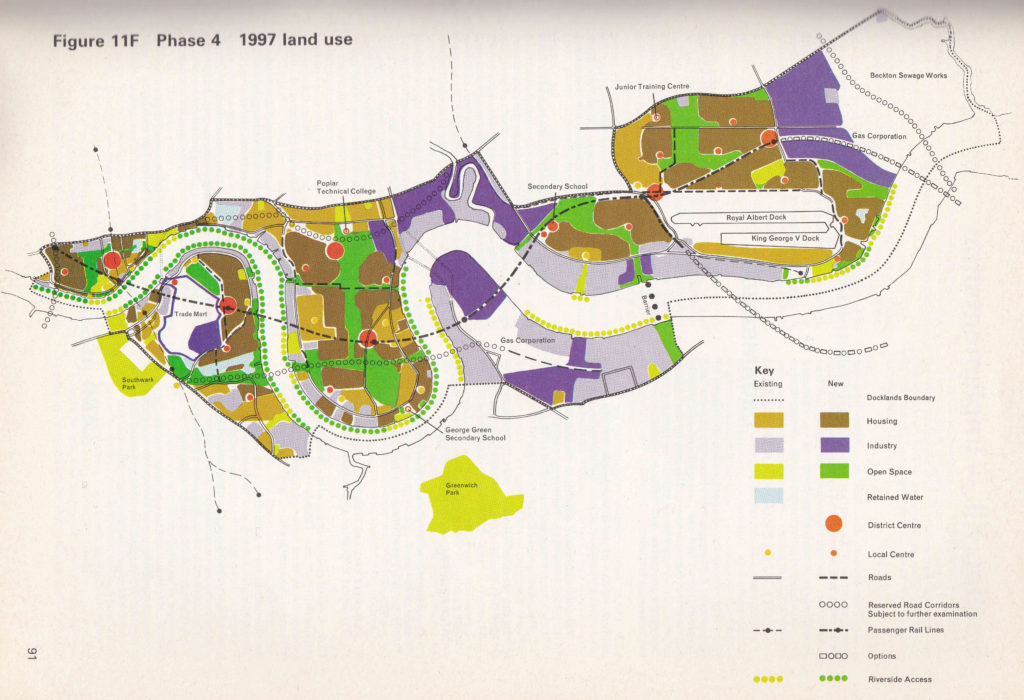

The plan was very comprehensive including the routing of roads, public transport, industry and housing. Four maps within the plan provided a summary of the Docklands Joint Committee’s recommendations for how land use across the docklands would transform over the coming years.

Docklands Development Phase 1 – Up To 1982

The first phase of docklands development would start to expand established district centres and new housing would be built in Wapping, around the Surrey Docks/Deptford area (expanding the existing Redriff estate) and new housing in the south-east quarter of the Isle of Dogs.

The development of large industrial zones would commence, centred on the Greenwich Peninsula and along the river to Woolwich, the areas around the River Lea and Beckton.

The targets of the district centres were:

- Wapping could have about 20,000 sq.ft of shopping, centred round a supermarket, together with a health centre, although this might be in temporary accommodation;

- On the Isle of Dogs the southern centre could have a shopping centre of about 60,000 sq.ft together with a health centre;

- Surrey Docks could also have roughly 60,000 sq.ft of shopping, centred around a large supermarket together with a health centre;

- The East Beckton centre could be the furthest developed, with around 60,000 sq.ft of shopping, a secondary school. health centre, and community centre

For transport, short-term improvements would be made to the North Woolwich and East London line along with improvements to bus services and existing roads.

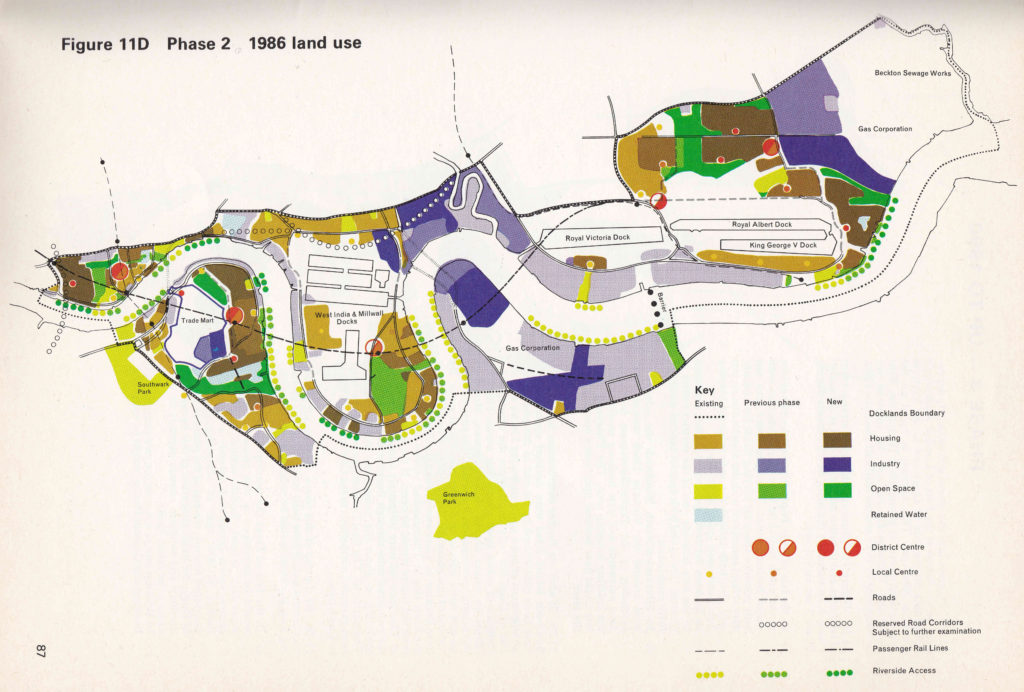

Docklands Development Phase 2 – Up To 1986

The second phase of docklands development continues the work of the first phase with expansion of housing in Wapping and the Isle of Dogs, with substantial new housing in Beckton. The plan proposed that by the end of phase 2 development across the Surrey Docks would be complete.

The plan was rather vague on new transport projects, however by the end of phase 2, the intention that a new underground line from Fenchurch Street Station would have been extended to Custom House. The strategy document described this new underground line as:

“New tube line (River line) – The Docklands Joint Committee have endorsed the proposed route from Fenchurch Street to Custom House but there are two alternative routes from Custom House to Thamesmead, shown dotted, which are to be further examined.”

In the map below, the River line is shown as a line of wide and narrow dashes out to just north of the Royal Victoria Dock. Other diagrams in the report show the two options for extending the route on to Thamesmead, one via Beckton and the other option via Woolwich Arsenal.

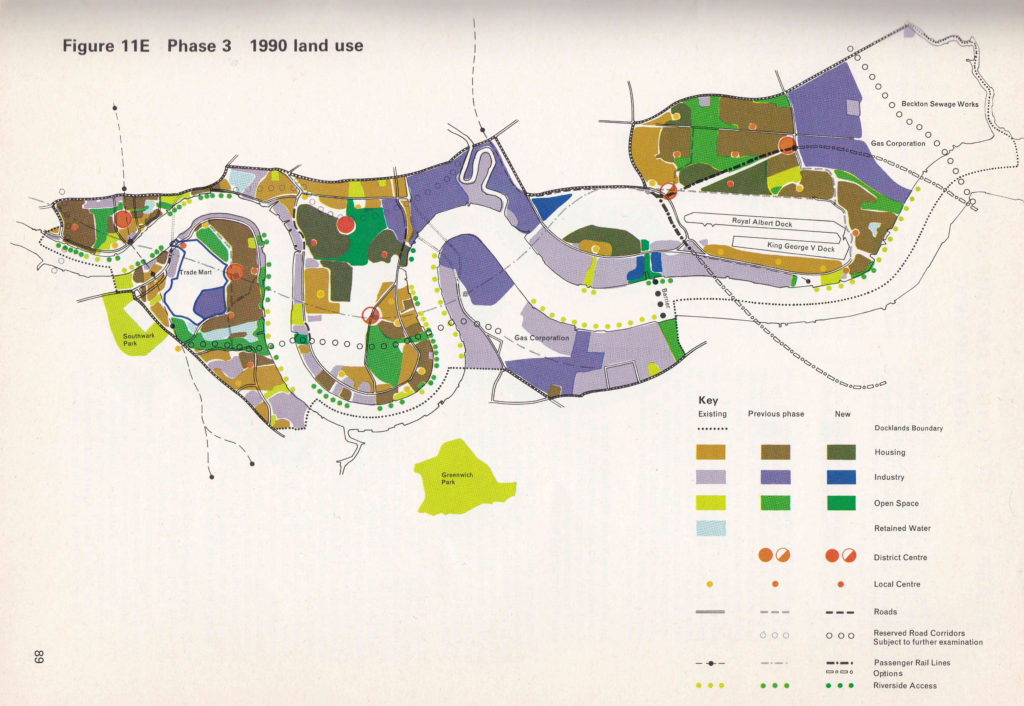

Docklands Development Phase 3 – Up To 1990

Phase 3 up to 1990 is where the major changes were implemented and would have resulted in a very different docklands to the area we see today.

Phase 3 included the filling in of the majority of the old docks, with the exception of the Royal Albert and King George V docks. The report does acknowledge that the ability to make these changes is very dependent on the future operations of the Port of London Authority on the Isle of Dogs and the Victoria Dock in Newham. This highlighted one of the key challenges for the Docklands Joint Committee in that they did not own any of the land across the docklands so the implementation of their proposals would be very dependent on large owners such as the Port of London Authority and the availability of significant funding.

Phase 3 aimed to address the lack of open space available to the residents of the Isle of Dogs and Poplar. In the north of the Isle of Dogs there is a new large area of green which the plan proposed as:

“The open space area not only provides space for playing fields for a secondary school associated with the district centre, but will also help relieve the deficiency of playing fields and open space in Poplar.”

Phase 3 would see the work in Beckton complete with new housing east of the district centre. In Silvertown and North Woolwich the release of land around the Victoria Dock would allow the extension of the Poplar and Silvertown industrial zones to the east.

For transport, phase 3 identified the possible route of a new road, the southern relief route (shown by the line of circles in the diagram below). The route shown would have involved two river crossings, complication by the need for opening bridges. The benefit of the route across the Isle of Dogs was, although dependent on the future of the Millwall Dock, it would pass mostly through vacant land. A disadvantage of the route was identified as the significant additional traffic the new road would feed into Tooley Street and the resulting addition to the congestion on the approach to Tower Bridge.

Docklands Development Phase 4 – Up To 1997

Phase 4 completed the development across the docklands, however still with options for train and road routes.

In the Isle of Dogs, there would be further additional housing, however the main feature is continuous open space from the north, through the centre of the peninsula, to link up with Mudchute in the south.

In the Silvertown and North Woolwich area, there would be additional housing and open space to occupy the area once covered by the Royal Victoria Dock.

The map shows the route reserved for the proposed road, and the two options for extension of the proposed River line on to Thamesmead.

The map for phase 4 shows how different the docklands would have been if the proposals of the Docklands Joint Committee had been implemented.

By completion, the allocation of the 5,500 acres within the Docklands area would have been:

- 1,600 acres for industry

- 1,600 for housing

- 600 acres of public open space and playing fields

- 600 acres for community services and transport

The remaining 1,100 acres was assumed to be still held by the Port of London Authority (the Royal Albert and King George Docks), the Gas Corporation at Greenwich and Beckton and the Thames Water Authority, also at Beckton.

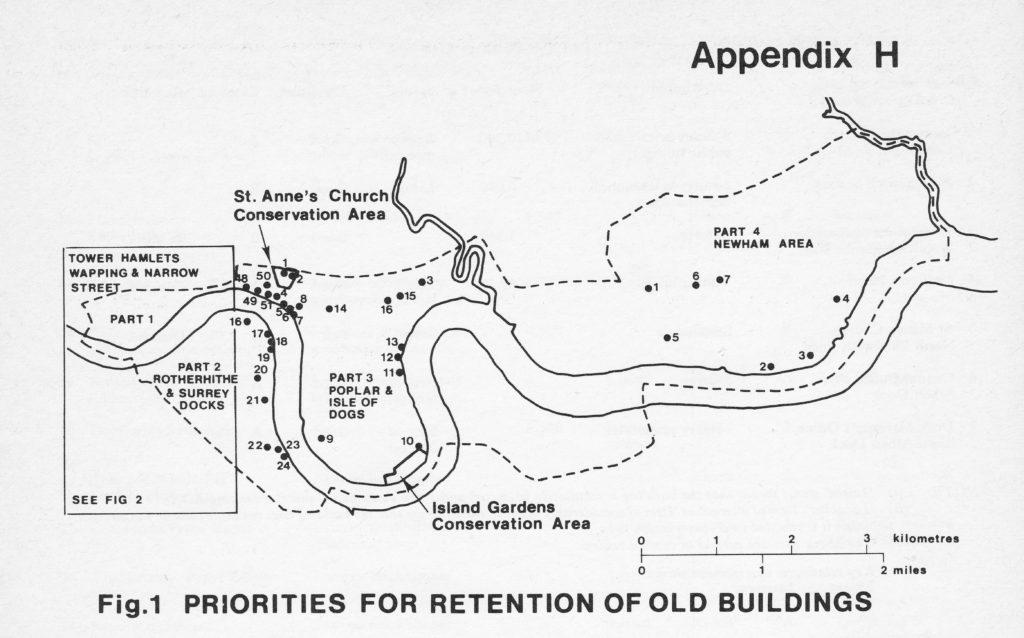

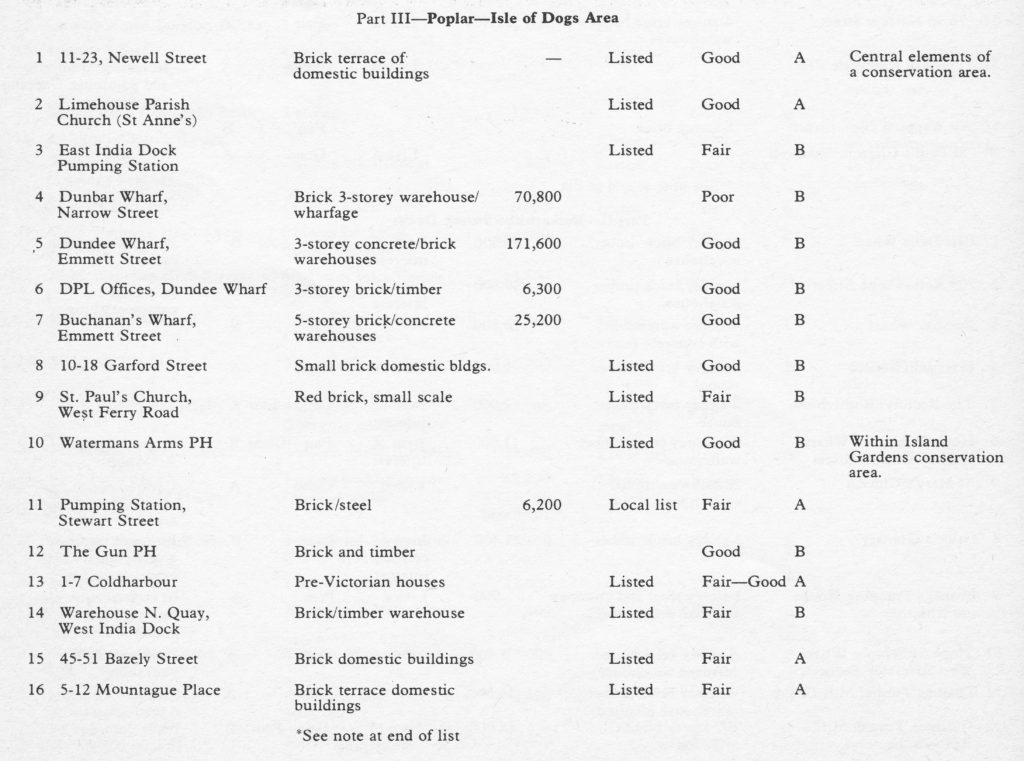

Although the report documented the considerable redevelopment of the whole Docklands area, the report also identified as a priority the need to retain many of the older buildings that could still be found across the area.

An appendix of the report listed 101 buildings that were a priority for retention. An extract from the appendix is shown below with one of the maps, and following a list of the buildings in the Poplar and Isle of Dogs area.

The number in the third column is the floor space, not a financial value.

The need in the report to list buildings that should be retained is similar to the 1973 Architects’ Journal on East London which also listed buildings across East London that were at risk. There was considerable concern that wholesale development of such a large area of land would include the destruction of many of the historic buildings that could be found across East London. Many of these had lost their original function which placed them at further risk.

Following publication, a number of problems were quickly identified with the proposals.

The emphasis on industrial and manufacturing space rather than office space did not align with the wider environment across the country with the gradual decline in manufacturing and the potential growth in financial services and wider service industries that was taking hold in London.

The Docklands Joint Committee had no real powers and no direct access to finance for the purchase of land and the implementation of the proposals. This was further complicated by the lack of local authority finance due to the economic conditions of the mid to late 1970s.

The Docklands Joint Committee was also intended to coordinate the response of the individual local authorities that covered the docklands, however all too often these local authorities acted in their own interest. Examples being the work of Tower Hamlets to relocate Billingsgate Market and to bring the News International print works to Wapping in the early 1980s.

The Docklands Joint Committee did try to bring in private finance late in the process, however this was opposed by some of the local action groups who did not agree to the use of private finance in the development of the area.

In the meantime, the people of the Docklands were getting more and more frustrated with the lack of action, endless studies and consultations, but no significant development. Jobs and people continued to leave the Docklands. When the Docklands Joint Committee report was published in 1976 the population of the Docklands was round 55,000 and by 1981 this had reduced to 39,000.

The House of Commons expenditure committee examined the work of the Docklands Joint Committee in 1979 and came to the conclusion that since the committee had been formed, very little had been done.

As well as coming in front of the House of Commons Expenditure Committee, 1979 was also the year of another event that would seal the fate of both the Docklands Joint Committee and their proposals when a Conservative Government was elected.

Michael Heseltine as the Secretary of State for the Environment created Urban Development Corporations, one of which would focus on the London Docklands as the London Docklands Development Corporation.

The objective of an Urban Development Corporation was stated in the Local Government, Planning and Land Act:

“Shall be to secure the regeneration of its area by bringing land and buildings into effective use, encouraging the development of existing and new industry and commerce, creating an attractive environment and ensuring that housing and social facilities are available to encourage people to live and work in the area.”

The Conservative ideology was also that private rather than public money would fund and drive much of the development of the Docklands.

Financial deregulation would also drive the demand for a new type of office space consisting of large open floor trading areas with the space to install the complex IT systems and their associated cabling that was a challenge in the more traditional buildings of the City of London.

The Docklands would change beyond recognition over the following years. The London Docklands Development Corporation published a glossy summary of their work in 1995 titled “London Docklands Today”. To emphasise the degree of change, the publication included a few before and after photos, including these of Nelson Dry Dock, Rotherhithe:

And these of the West India Docks in 1982 and 1993:

The Docklands area today continues to develop. The Isle of Dogs seems to be a continual building site, however it could have all been very different if the proposals of the Docklands Joint Committee were not now just an interesting footnote in the development of London.

Thank you for that. I think I interviewed all the ex-chairs of the Docklands Joint Committee who were still alive in the mid-1990s. Have no idea what happened to my notes, but I did, sort of, write some of it up. The archive material was not at LMA but in a store and inaccessible. A lot of stuff went to the Docklands Museum – several van loads and a lot left. No idea what has happened to that now. I think I have a copy of the Hestletine report somewhere. The interesting thing, for me, was why Greenwich Peninsula was removed from the DJC area and not put into the LDDC. That may, or may not, have been a good thing!!

https://www.amazon.co.uk/Beyond-Tower-History-East-London/dp/0300187750

I am working my way through this at present, an excellent piece of research and history. Haven’t got to the bit about the docks and the redevelopment but I am sure it will be fascinating.

I don’t know what other people think but it seems to me that the mid-70s plans would have made East London a far nicer place. Look at all that “green space”!

Dear London Inheritance

I work for Full Fat TV and we’re producing a series for Channel 5 about the River Thames with Tony Robinson. Who could I speak to about getting some of these images featured in this blog/entry?

I can be contacted at varsha.chauhan@fullfattv.co.uk

I look forward to hearing from you.

best wishes

Varsha

are you looking for comments on the Strategic Plan? As I said above its probably still possible to contact people involved in it. There should be a vast archive of comment and criticial papers – there were a number of organisations doing this. I helped Museum in Docklands acquire 3 van loads of archive material and there was much else. Many of the people who produced this documentation are still around.

are you looking for comments on the Strategic Plan? As I said above its probably still possible to contact people involved in it. There should be a vast archive of comment and criticial papers – there were a number of organisations doing this. I helped Museum in Docklands acquire 3 van loads of archive material and there was much else. Many of the people who produced this documentation are still around.

Hi Mary

It’s more the photographs in this blog. I’ll try the Museum in docklands. if you have a contact that would be great.

best wishes

Varsha

Hi Mary, thanks so much for saving those van loads for the Museum. I am currently trying to find out more about wapping in the mid 1980s regarding redevelopment and general life. I am off to the MoD in September, but do you recall anything about residents and full resident consultations etc? I know the isle of dogs had a more organised resistance, but wasn’t sure if this experience

Re the Docklands Forum and Joint Docklands Action Group – I think this is still at the MoD, but that the London Met Archives have the LDCC archive now with some bits in Tower Hamlets Local Museum.

No – sorry – all the people I knew there are gone. Good luck anyway

Email so I can reply privately

There is lots of material at the National Archives – if you would like help navigating it please ask

Most of it is in the AT 41 class – London Planning – but there a bits and pieces tucked away everywhere