Two apparently unconnected subjects for this week’s post. A Billingsgate excavation, and the London Docklands. What connects the two is that whilst sorting a box of papers this last week, I found leaflets handed out to visitors when it was possible to visit the archeological excavation in the old lorry park at Billingsgate Market, and the London Docklands Development Corporation Visitor Centre on the Isle of Dogs.

I had posted some photos of an excavation a few months ago, asking for help to confirm the location, and a number of readers suggested Billingsgate. I was really pleased to find the Billingsgate leaflet because it helped to confirm the location.

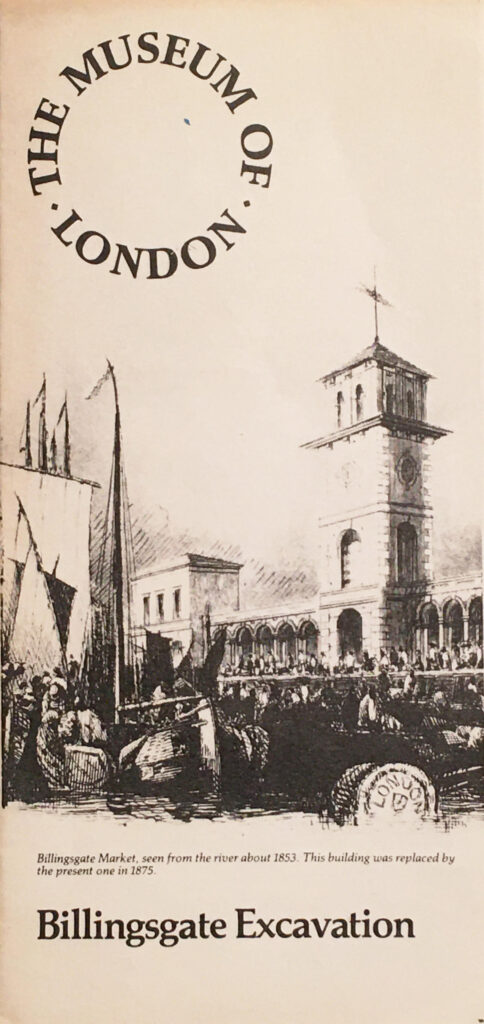

Billingsgate Excavation

Billingsgate fish market moved to a new location between the Isle of Dogs and Poplar in February 1982, and whilst the buildings of the fish market were to be retained, the adjacent lorry park was to be redeveloped with an office block. The lorry park was in a prime position between the River Thames and Lower Thames Street and offered a sizeable area for new offices.

Archeologically, the site of the lorry park was important. It had been built on the area of land that was once the shifting waterfront between land and river. The Thames has only relatively recently been channeled within concrete walls, many centuries ago, the river’s edge would have been marsh, inter-tidal land up to where the ground rises north of Lower Thames Street.

As the importance of the City as a trading port grew, the edge of the City expanded into the river, building quayside, docks and buildings from the Roman period onwards.

It was this advance of the waterfront that the excavation hoped to uncover below a tarmac lorry park.

In 1982, the Museum of London published a leaflet explaining the Billingsgate Excavations and it was this leaflet I found in a box of London guides and leaflets.

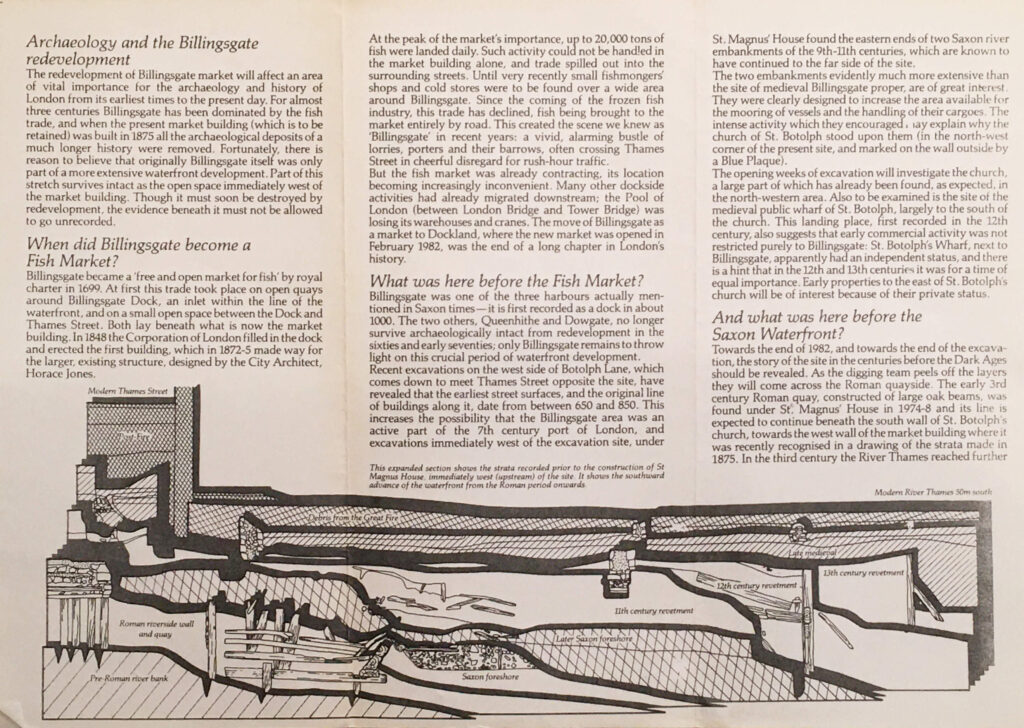

The leaflet was published during the early weeks of the excavation, and provided some background to the location and included a drawing showing the results from a previous nearby excavation at St Magnus House which had found evidence of the Thames waterfront as it expanded southwards from the Roman period to the 13th century. A continuation of this Roman to 13th century strata was expected to be found under the Billingsgate lorry park.

Long before the fish market, Billingsgate had been one of the three docks or harbours dating from the Saxon period, along with Queenhithe and Dowgate. These later two sites had been lost to archeological investigation due to development in the 1960s and early 1970s, so access to the Billingsgate lorry park was of considerable importance.

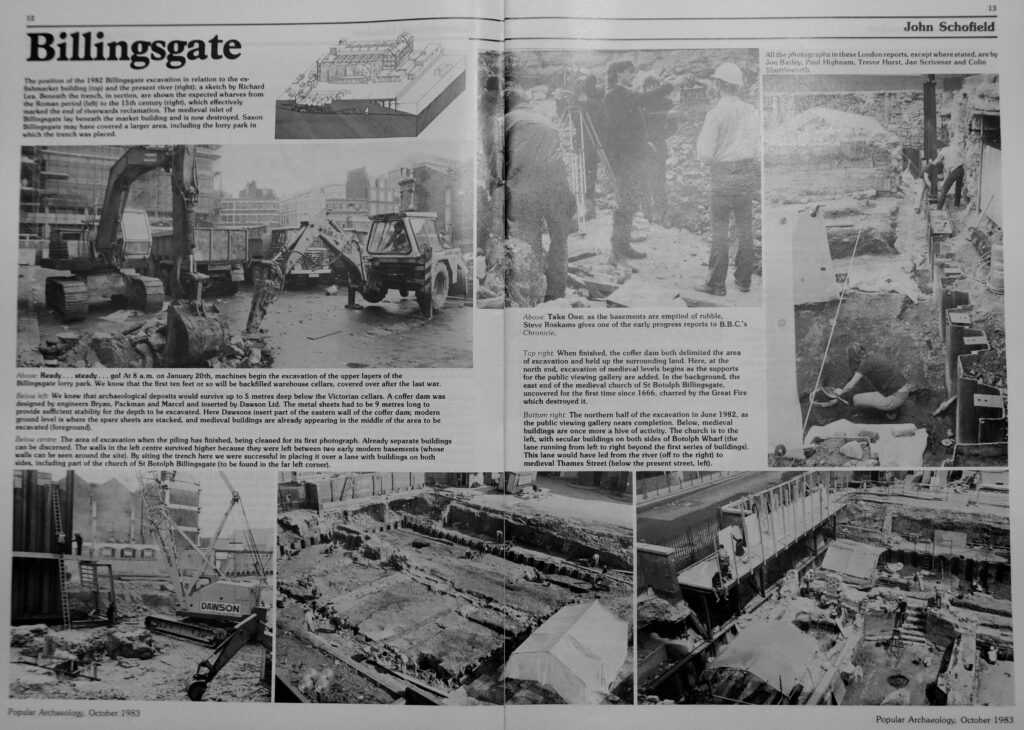

Preparation of the site began on the 20th January 1982 when the tarmac was removed, along with rubble found in the basements of the buildings beneath the tarmac. A cofferdam needed to be installed to shore up the sides of the site and prevent water entering the excavation at times of high tide. The waters of the Thames would still try and seep through the land the river had lost. The work to excavate the site began in March.

The leaflet explains the source of funding for the excavation, from the Corporation of the City of London, the Department of the Environment and from a number of private contributions. A reminder of the expense of such projects and the considerable challenges of raising funds for such important work, as when these sites have been lost, there will never again be a chance to explore the history of the site.

I had photographed the lorry park in 1980, when the market was still open. Rather a bland view when you consider what would be found below ground.

I took a number of photos of the excavations when I visited the site. When I originally scanned the negatives I was not sure of their location (I was not good at keeping records of the location of my photos), and I published a couple in a post a few months ago asking for help with the location. A number of readers suggested Billingsgate, and finding the leaflet helped jog my memory of visiting the site.

The Billingsgate excavation uncovered a significant amount of evidence of the waterfront as it developed, and the buildings that lined the river.

Excavation of the upper levels found evidence of the waterfront dating back to the 12th century, along with tenements that lined the river (extending into the Billingsgate lorry park from other tenements discovered during earlier excavations to the west). A small inlet from the river was also discovered under the lorry park.

The church of St Botolph Billingsgate was originally just north of the site, where Lower Thames Street is today, however part of the church did extend into the area of the lorry park, and evidence of the southern wall was found, along with two tiled floors from the church and a number of burials.

Numerous small finds were uncovered, including a rare 14th century buckle, a lead lion badge, which could have been a pilgrim’s badge and intact 17th century bottles.

A number of fabrics dating back to between the 12th and 14th centuries were found. These were made of undyed, natural fibres, the type that have been used for sacking, probably evidence of the transport of goods from ships at the inlet and Billingsgate waterfront.

The Billingsgate dock may have been used by larger ships that would have been used for cross channel trade. Documentary evidence from the 14th century implies that these ships were encouraged to use Billingsgate rather than navigate through London Bridge to Queenhithe.

If you look in the middle of the following photo, there appears to be a number of twigs and branches laid out to form a mat. This is wattle consolidation in front of the 12th century waterfront.

In the following photo, a three sided wooden long rectangular box like structure can be seen:

This is a wooden drain that dates to the 13th century, possibly around 1270. The drain extended for a length of 8.8 metres, parts also had the top covering, and the drain was in exceptionally good condition allowing the detail of construction to be examined.

The results of the Billingsgate and related excavations, were published in the 2018 book “London’s Waterfront 1100-1666: excavations in Thames Street, London, 1974-84” by John Schofield, Lyn Blackmore and Jacqui Pearce with Tony Dyson. The book is a detailed examination of London’s historic waterfront as it developed over the centuries.

The book is published by Archaeopress, and is available for download under Open Access.

The book includes a photo of the same drain that was in my photo, and as Archaeopress appears to state that the book comes with a Creative Commons licence, I have copied the photo from the book below.

The drain is exactly the same as in my photo, so final confirmation that my photos were of the Billingsgate excavation.

The Billingsgate excavation was a significant dig during the early 1980s. I found some of my old copies of Popular Archeology from the time, and there are a number of articles by John Schofield providing updates on the work.

The following photo shows how far down the excavation had reached when I photographed the site, however it would continue downwards to reach the timbers of the Saxon and Roman waterfront, showing just how far below the current surface of the City that these remains are found.

The excavation was initially scheduled to end in November 1982, however agreement with the developer allowed work to continue into 1983.

Excavation finally worked down through the Saxon waterfront to the substantial timbers of the Roman waterfront.

As well as providing comprehensive coverage of the excavation, told by those working on the site, it also shows how this type of work was carried out in the early 1980s, and “because the dig has extra funding from sponsors, the Museum of London can invest in computers for the first time”. Very early use of computer technology to record a large excavation.

When work completed, a large number of finds were ready for further investigation. Wood from the various waterfronts had been removed, and sections of wood cut out to allow the age of the tree and when it was cut down to be investigated.

The BBC Chronicle programme shows the pressures of City archeology, the pressure to complete by a date driven by the developer, negotiations for extensions and how work is planned to retrieve as much as possible within a limited period of time.

Today, the site is under the building at the western end of the old Billingsgate Market building, at the far end of the following photo.

The following photo shows a very different view from roughly where I was standing to take the 1980 photo of the old lorry park.

Finding the leaflet on the dig, along with reading the book and watching the Chronicle episode brought back a load of memories from visiting the site almost 40 years ago. An advert in Popular Archaeology of July 1982 states that the site was open for visitors every day of the week except for Monday, and admission to the viewing platform cost 50p for adults and 25p for children.

Preserving timbers exposed to the air, when they have been buried in waterlogged soil for centuries is a considerable problem, however it would have been really good if some section of the old Roman and Saxon waterfront could have been preserved in situ. It would have provided a really good demonstration of how the present City has been built on the layered centuries of previous development, and as the City has risen in height, so the Thames has been pushed back into the the confined channel that the river runs in today.

Another of my finds whilst sorting through a box of London papers was a reminder of a very different visit.

London Docklands – The Exceptional Place

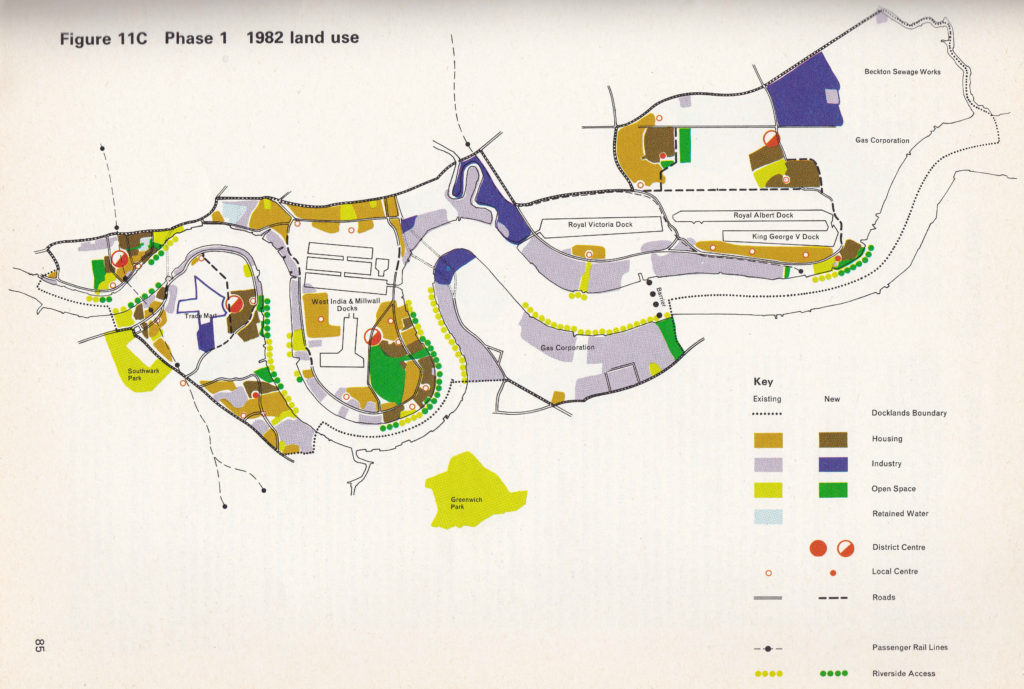

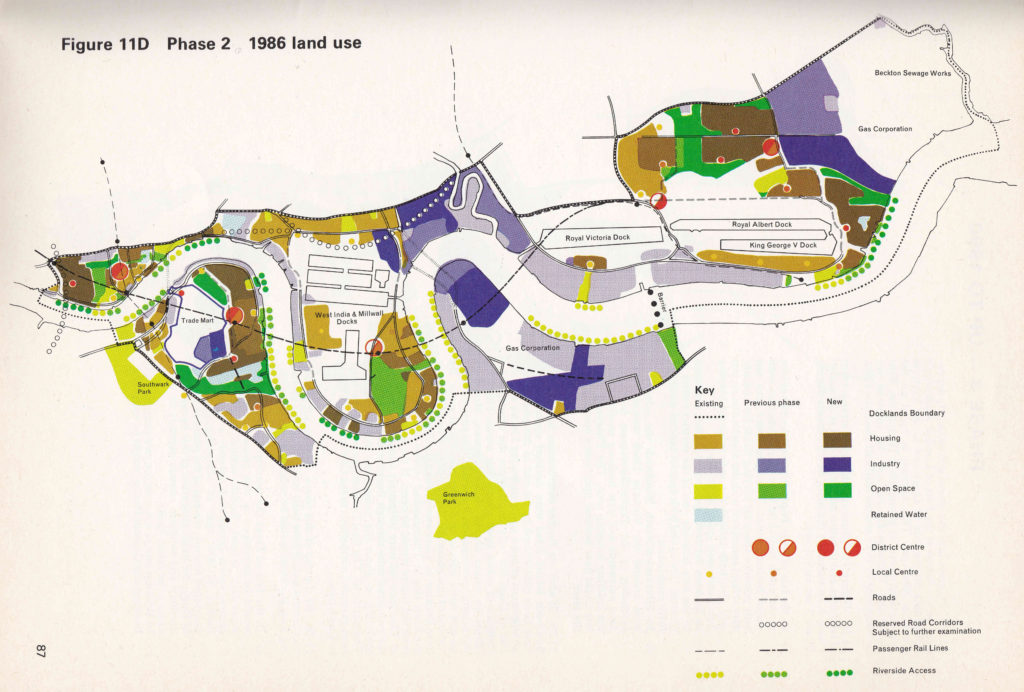

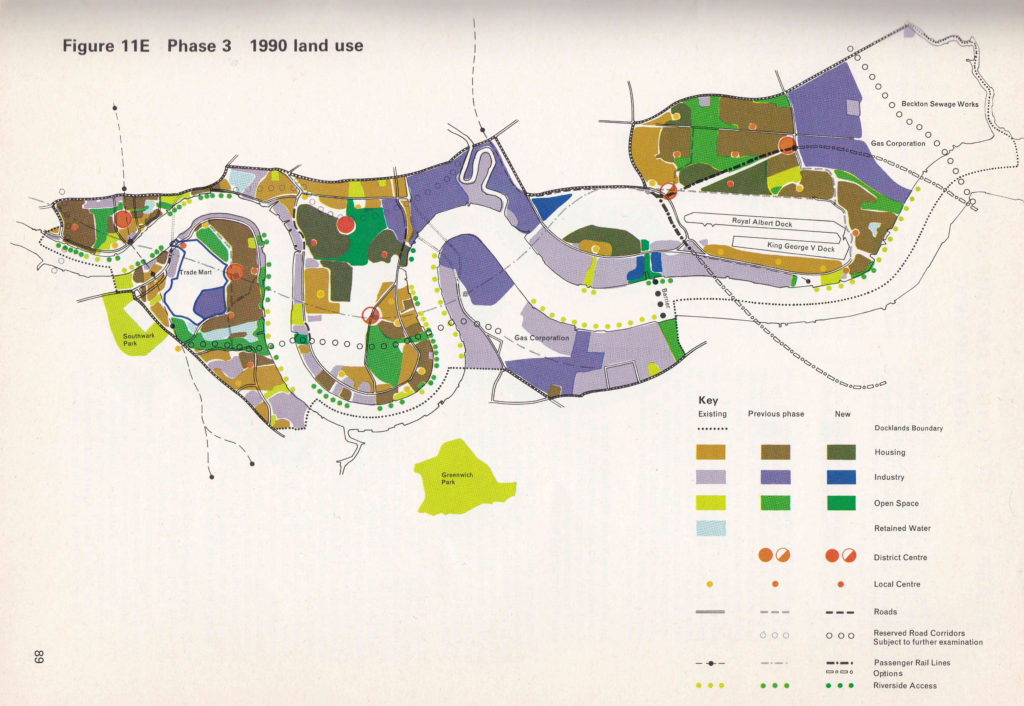

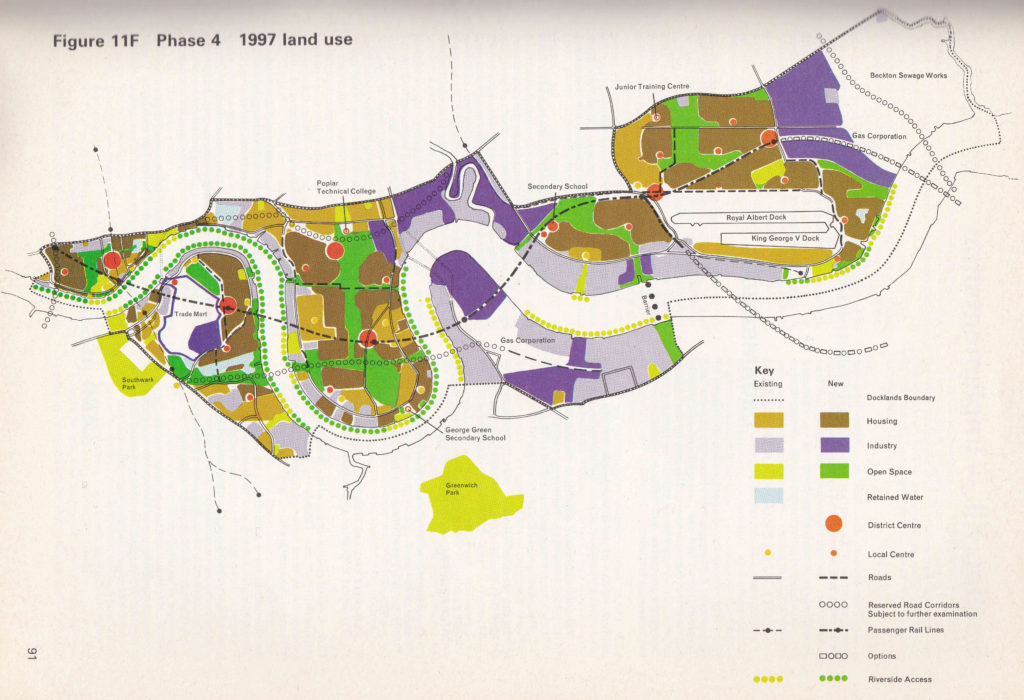

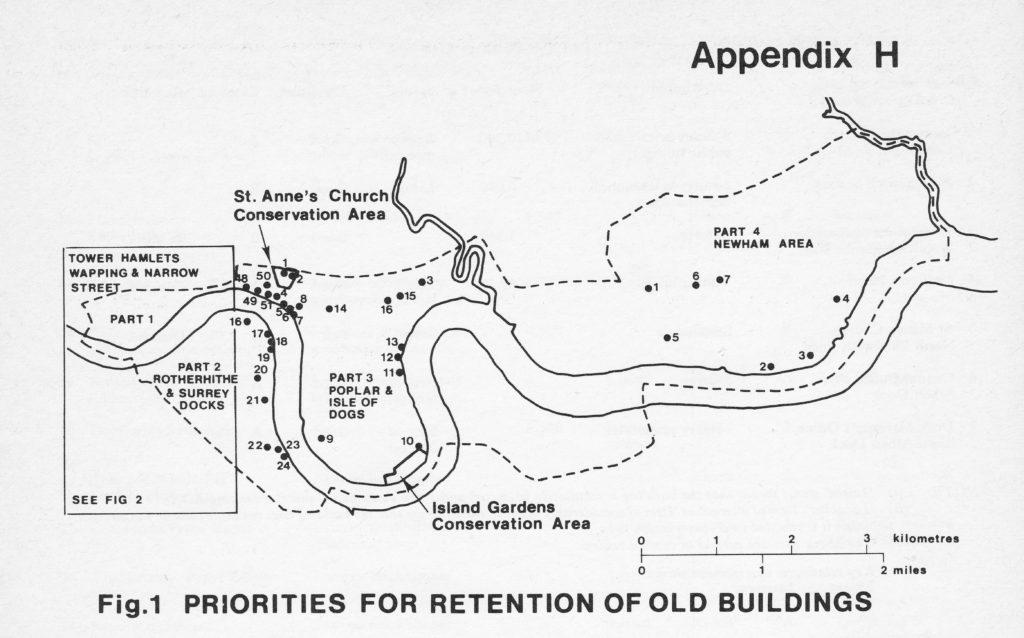

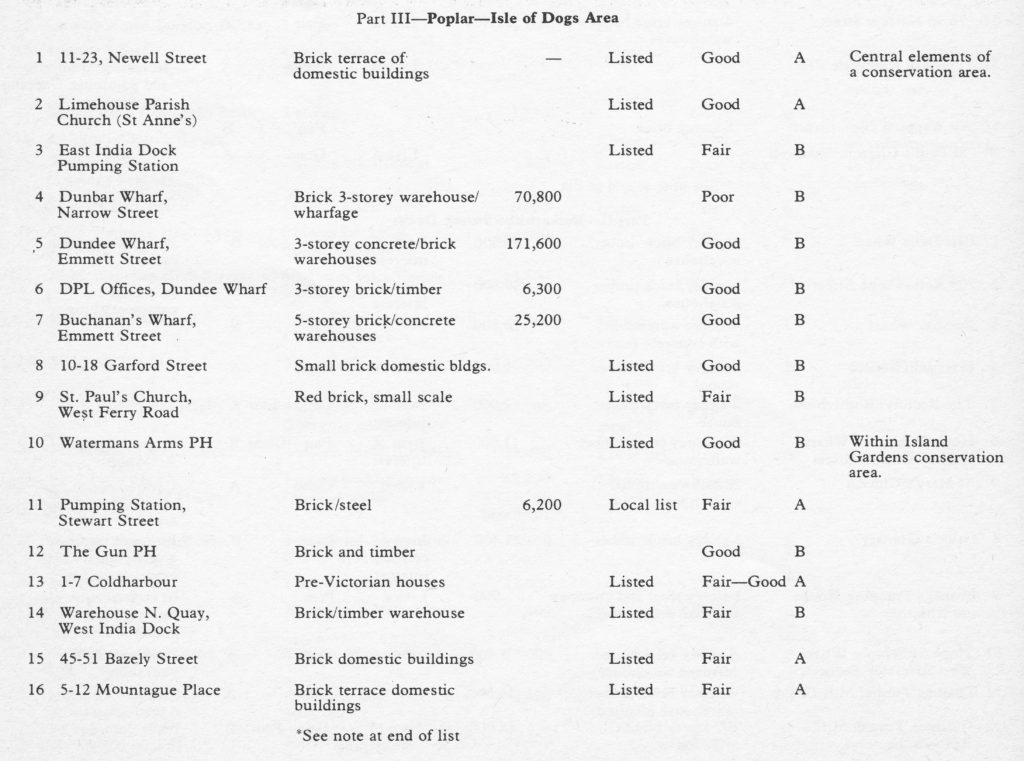

In the late 1980s / early 1990s, the redevelopment of the old docklands, around the Isle of Dogs and the Royal Docks further to the east was moving forward under the management of the London Docklands Development Corporation (the LDDC).

The LDDC opened a visitor centre at 3 Limeharbour on the Isle of Dogs, where a brochure on the London Docklands – The Exceptional Place was available:

The rear of the brochure, shows a train on the recently opened section of the Docklands Light Railway (DLR).

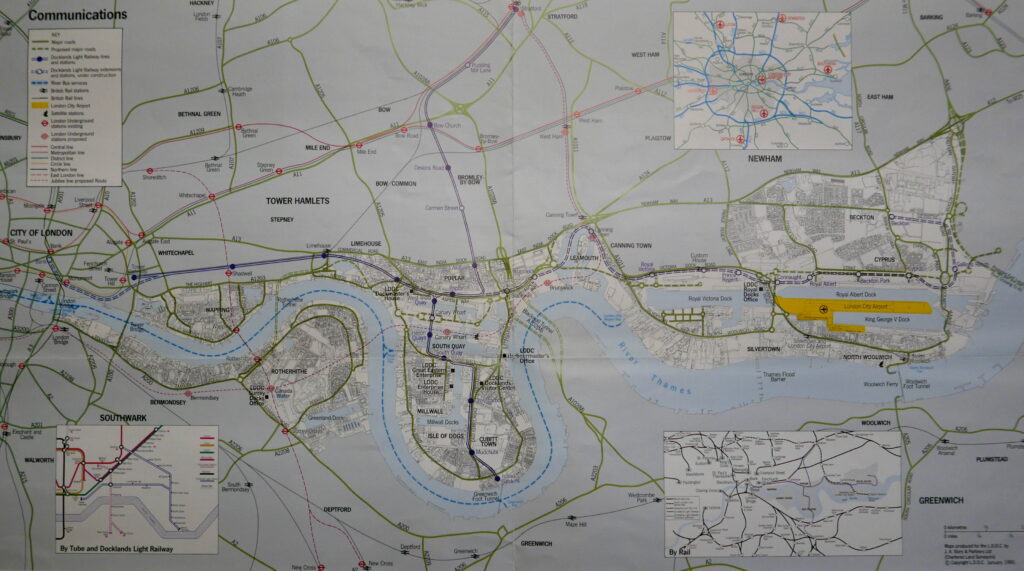

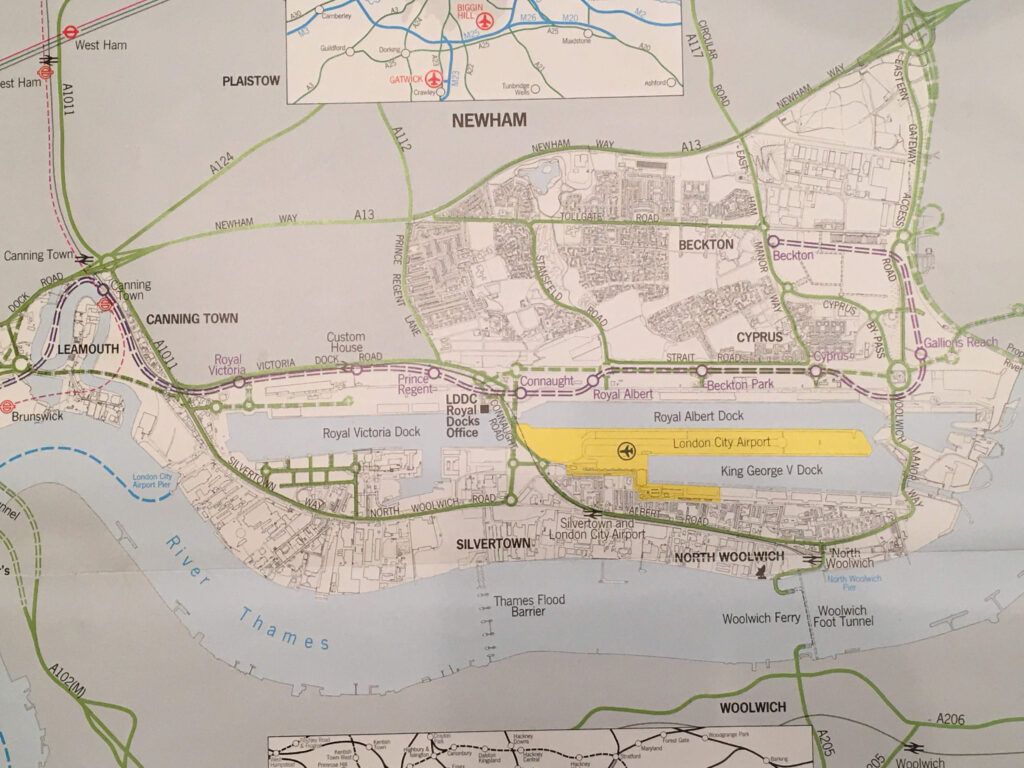

The brochure opens up to reveal a large map of the area, from the City of London in the west, to the edge of the Royal Docks in the east. Having a map is probably why I picked up and kept the brochure – anything with a map.

The focus of the map is on the transport links connecting the docklands to the City and the surrounding road network. Only recently this area of London had seemed a remote and derelict land and if the LDDC were to entice the investment needed, along with the businesses and people to relocate to the docklands, they had to demonstrate that travel was easy.

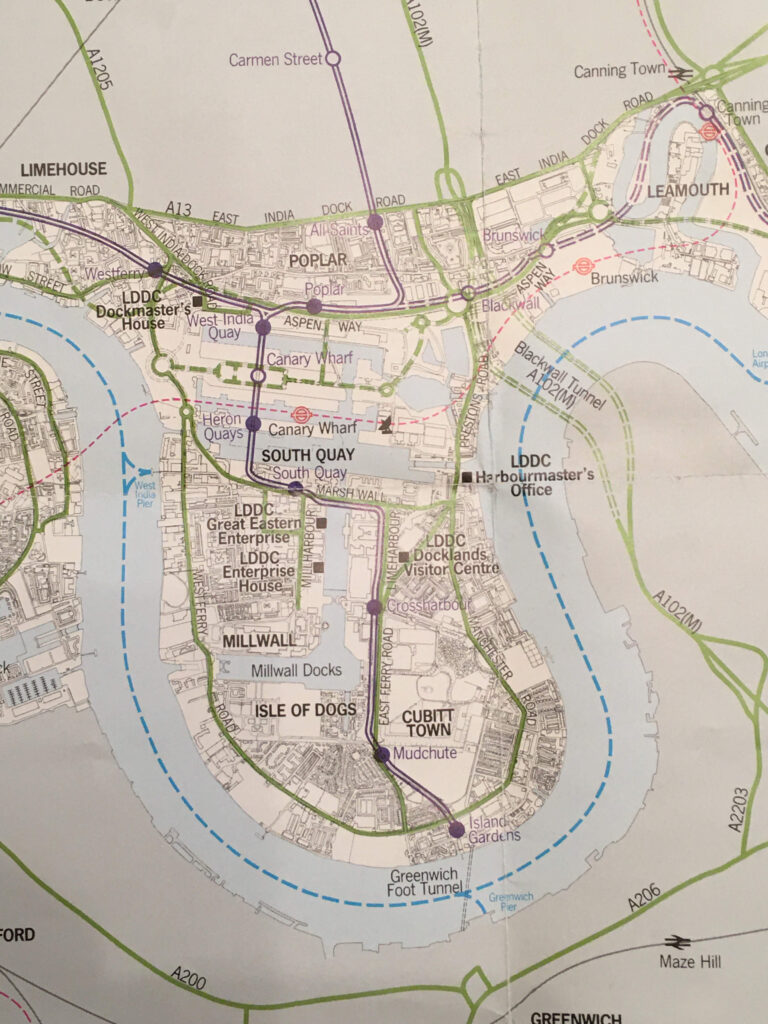

The map charts the growth of the Docklands Light Railway, and shows the extent of plans in 1990, along with some station changes to the DLR network we see today.

By 1990, the DLR extended from Tower Gateway in the City, to Stratford, and Island Gardens on the southern tip of the Isle of Dogs. The eastern route onwards from Poplar was shown as a dashed route to show that this section of the route was under construction.

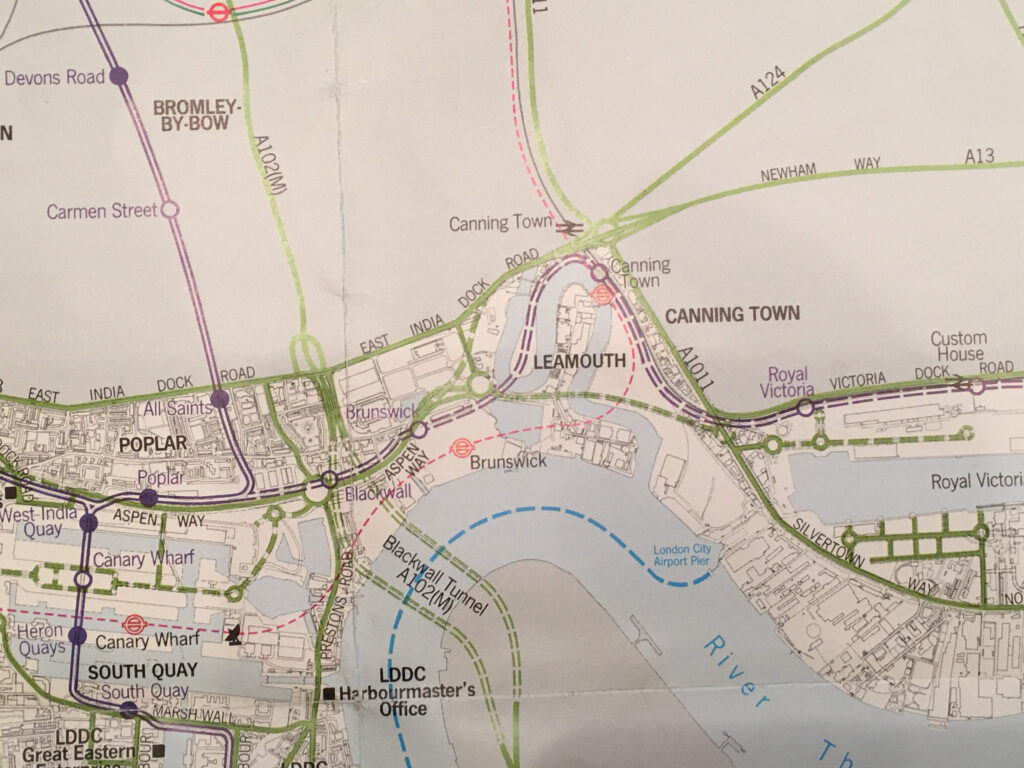

The following section shows the north eastern tip of the isle of Dogs and Leamouth, with the River Lea / Bow Creek curving around an area of land that has now been redeveloped as City Island.

The red dashed line shows the 1990 expectations for the planned Jubilee line extension, where the line would continue from Canary Wharf, to a new station called Brunswick, then to Canning Town and on to Stratford.

As built, the Jubilee line extension took a different route, and headed across the river to North Greenwich from Canary Wharf, before heading back across the river to Canning Town. Brunswick station would never be built.

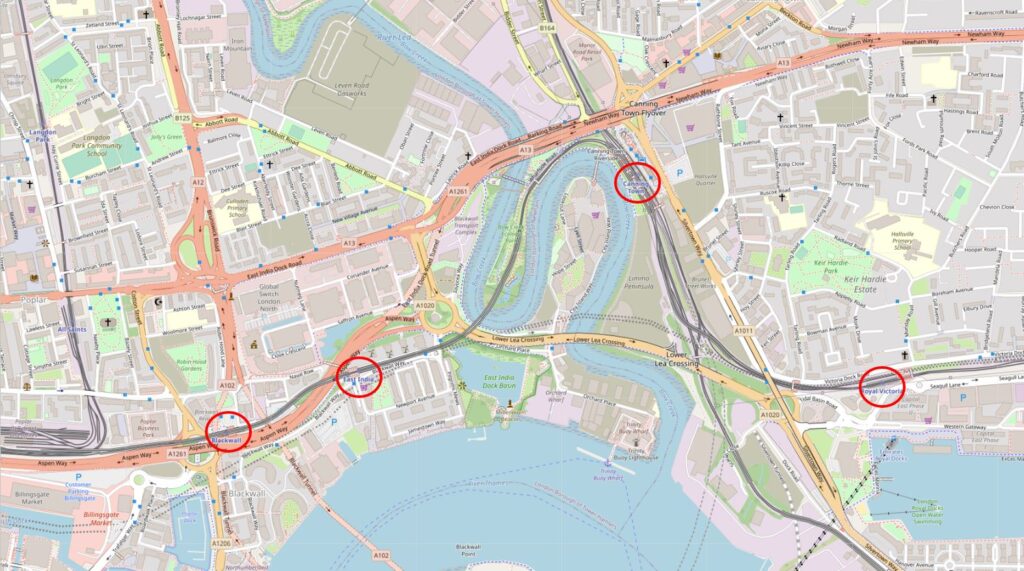

Comparing the planned to the built route of the DLR shows a similar loss of the name Brunswick for a station. In the 1990 plans, there was to be a Brunswick station on the DLR, however as built, this would be named East India. The following map marks the location of DLR stations today:

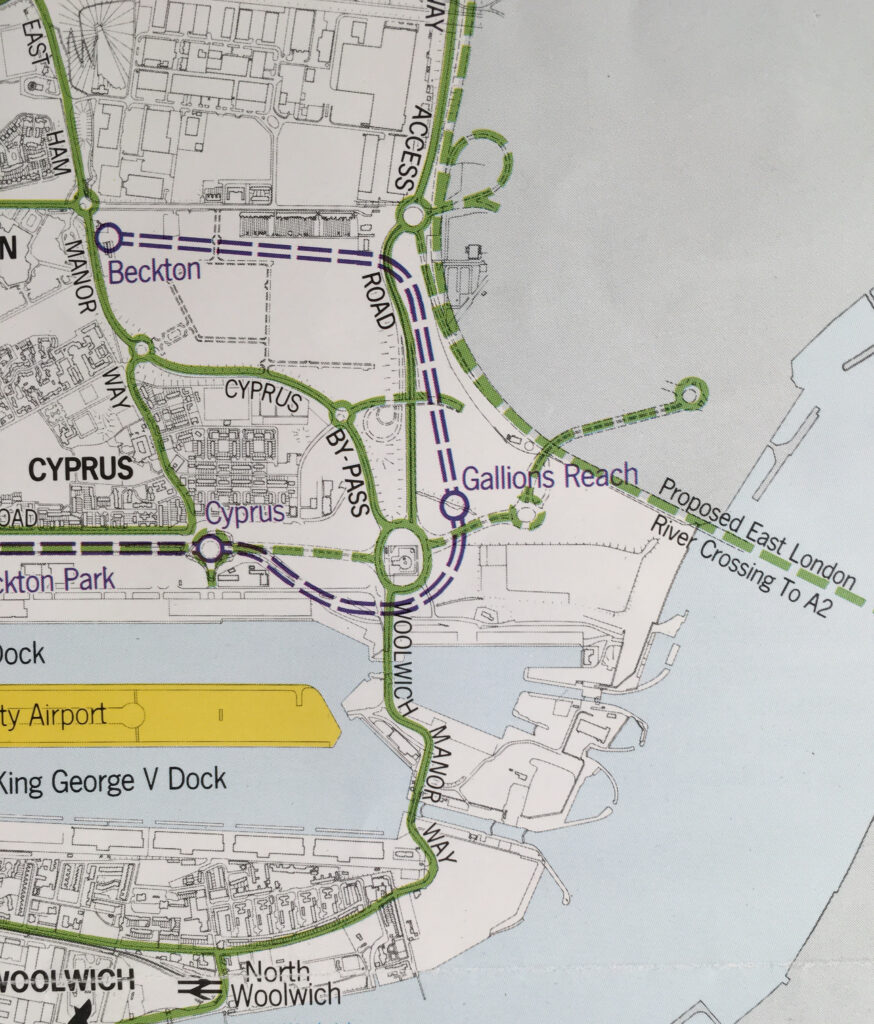

The route further east to Beckton shows the loss of a station. Connaught Station was planned between Prince Regent and Royal Albert stations, however when looking at the map, Connaught would have been so close to Royal Albert that it made little sense to build the station.

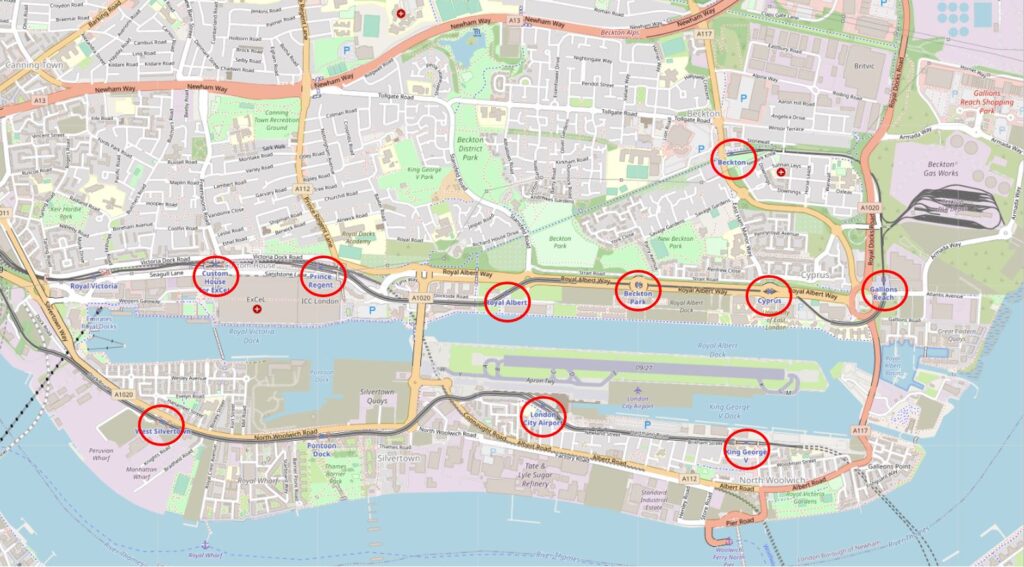

The yellow area in the above map is London City Airport, which had opened three years earlier in 1987. The map also shows the 1990 planned extension to the DLR, and the map below shows the line as built today.

The 1990 plan was for the line to run along the north of the Royal docks, however in the late 1990s and early 2000s, the line was further extended to Greenwich, Lewisham, City Airport and Woolwich.

The route south of the Royal Docks is shown on the 2020 map above, not on the 1990 map, and in the 1990 map, the line terminates at Island Gardens to the south of the Isle of Dogs, rather than crossing under the river and continuing on to Lewisham as it does today.

The map also identifies another element of transport infrastructure that has not been built – the East London River Crossing is shown on the eastern edge of the map from Gallions Reach, heading under the river towards the A2.

Ideas for this tunnel keep resurfacing, however it is not on Transport for London’s list of new river crossings for London, and I suspect given current financial conditions, the Silvertown Tunnel will be the only new river crossing built for a very long time.

Two very different topics, the only apparent connection being the leaflet and brochure coming from a box of London papers. There is though another connection – they both tell of the development of London. With Billingsgate we can discover the growth of London’s waterfront from the Roman timbers found many feet below the current surface level, through the Saxon and Medieval to a lorry park that served the old fish market.

In the London Docklands, development continues to this day, and the brochure records some of this and shows how the 1990 plans developed to the transport network we see today.

It is interesting to speculate whether archeologists in 2000 years time will discover any remains of the DLR and what they will make of a 20th century transport system.