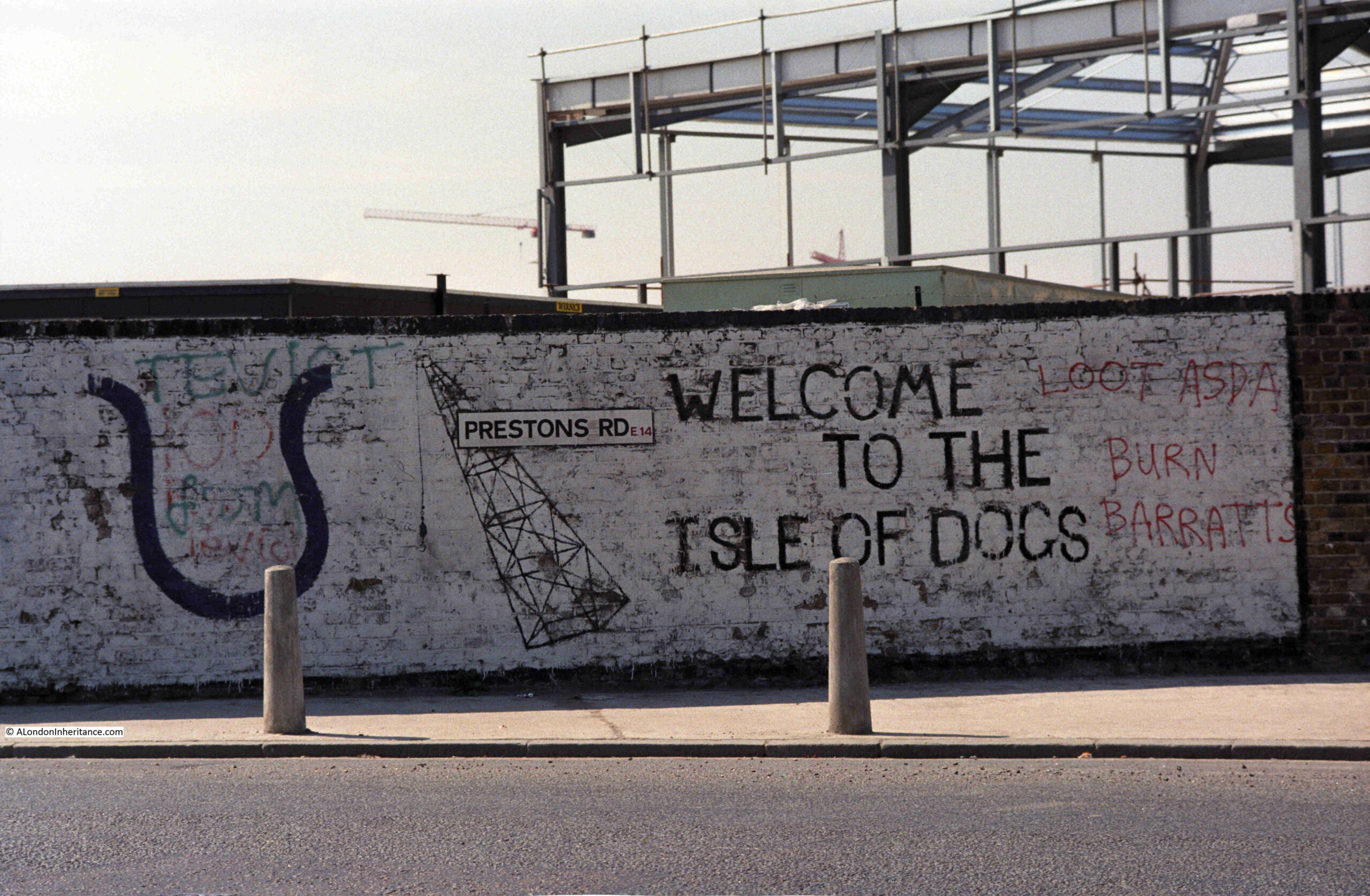

In 1986, my father photographed some graffiti on a wall in Prestons Road which runs from Poplar to the Isle of Dogs.

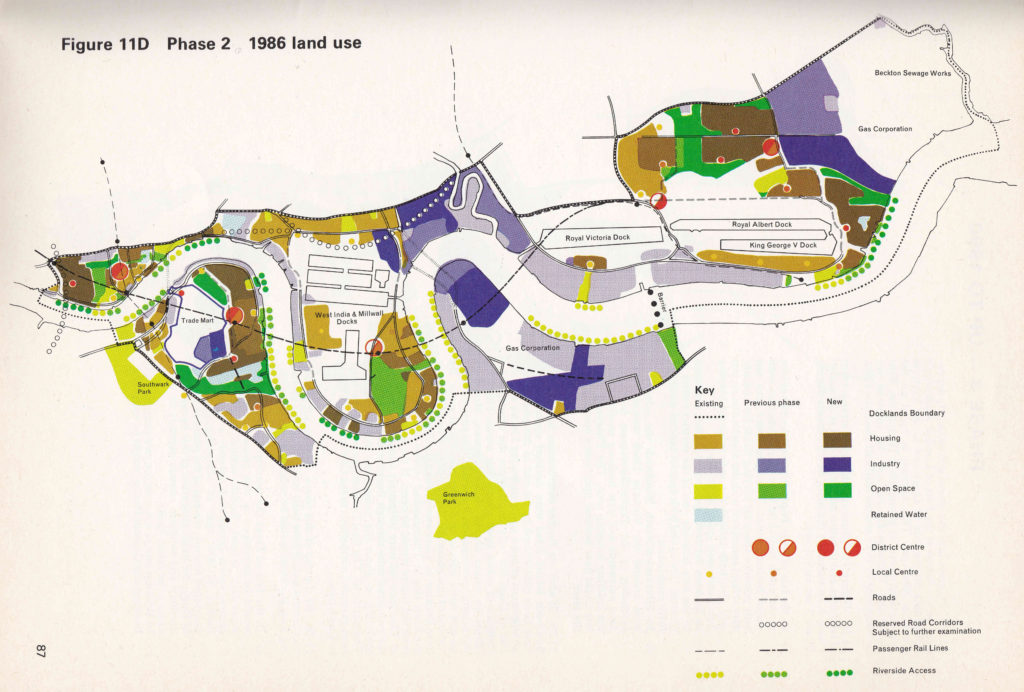

The 1980s were a traumatic time for the residents of the Isle of Dogs. The docks had closed and the developments that would lead to the office complex around Canary Wharf, as well as many new housing developments, were underway.

Much of this new development would not directly benefit local residents. Thousands of office jobs for those living outside of the Isle of Dogs, and new homes being built which were typically much more expensive than traditional homes in the area. Very little of the money being poured into new developments would find its way to the original residents.

The graffiti on the wall in Prestons Road reflects some of the anger and frustration felt as a result of the developments. Barratts the builders are mentioned on the right of the wall, along with Asda.

Whilst the build of a new Asda store could have been seen as a positive for residents, in reality it was one of the many cultural changes imposed, where centralised shopping would badly impact the trade of multiple small, often family owned shops.

The graffiti was on a wall in Prestons Road. This road runs from a junction with Poplar High Street down to the so called Blue Bridge, which crosses the east entrance to West India South Dock from the Thames.

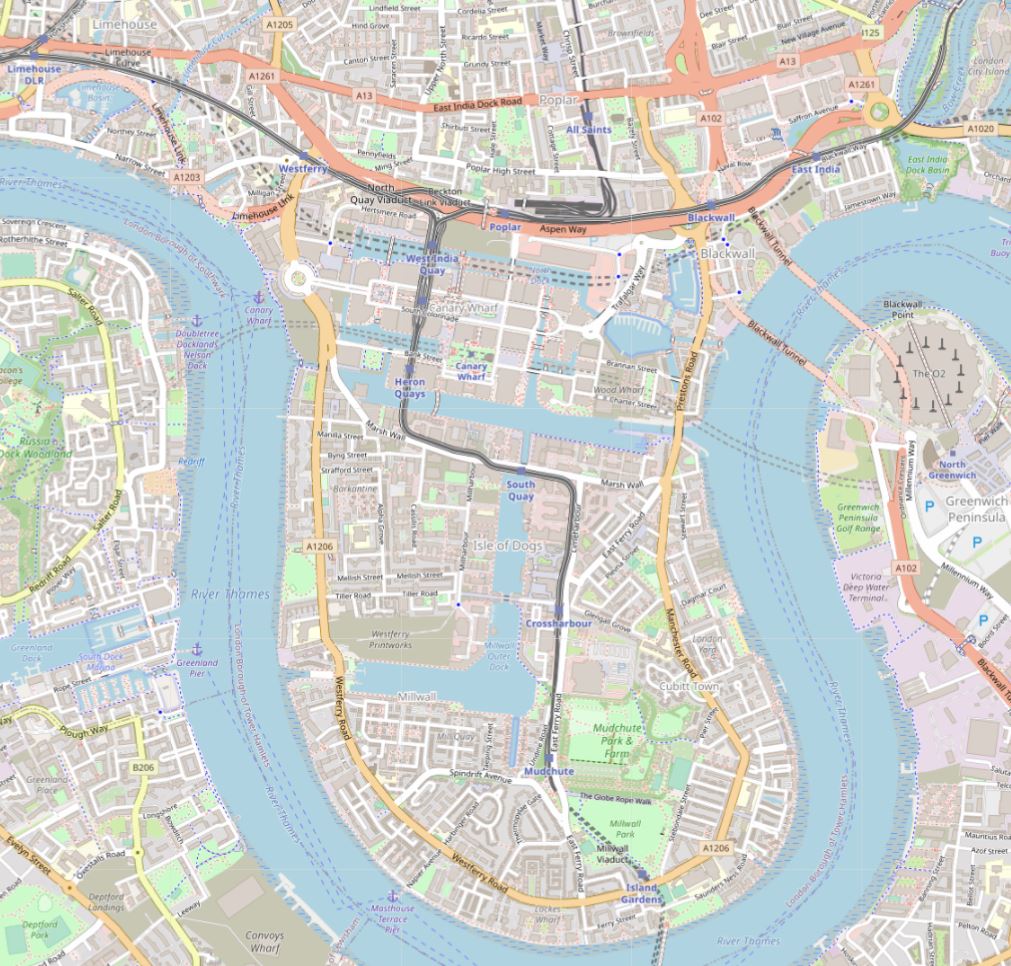

I have marked the two end points of Prestons Road in the following map. The road runs between these two points (© OpenStreetMap contributors):

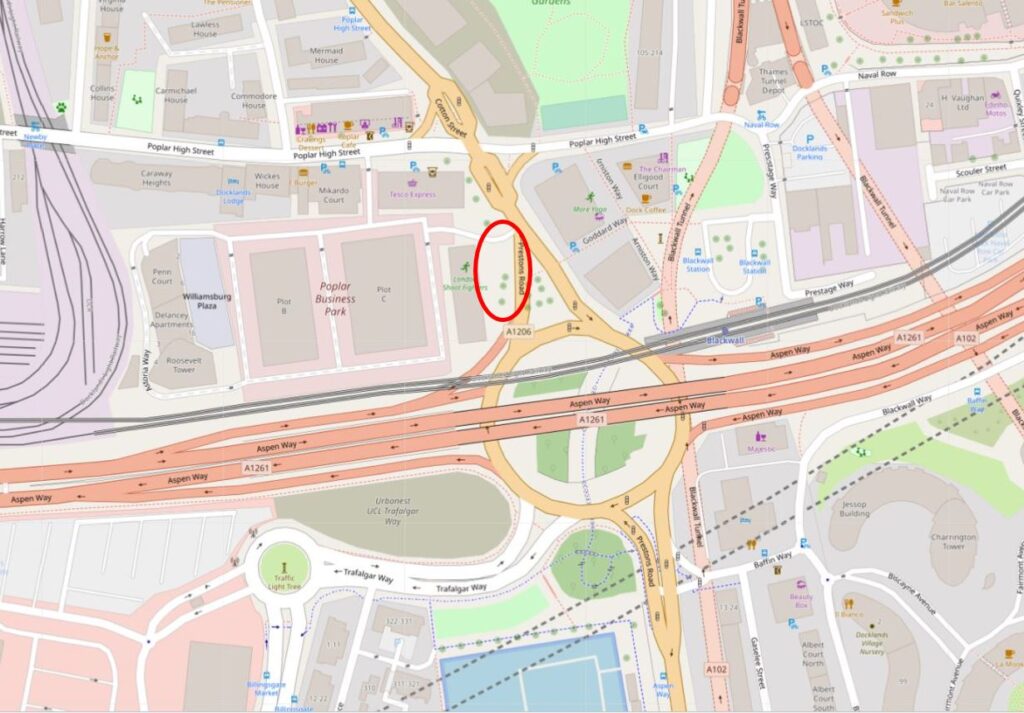

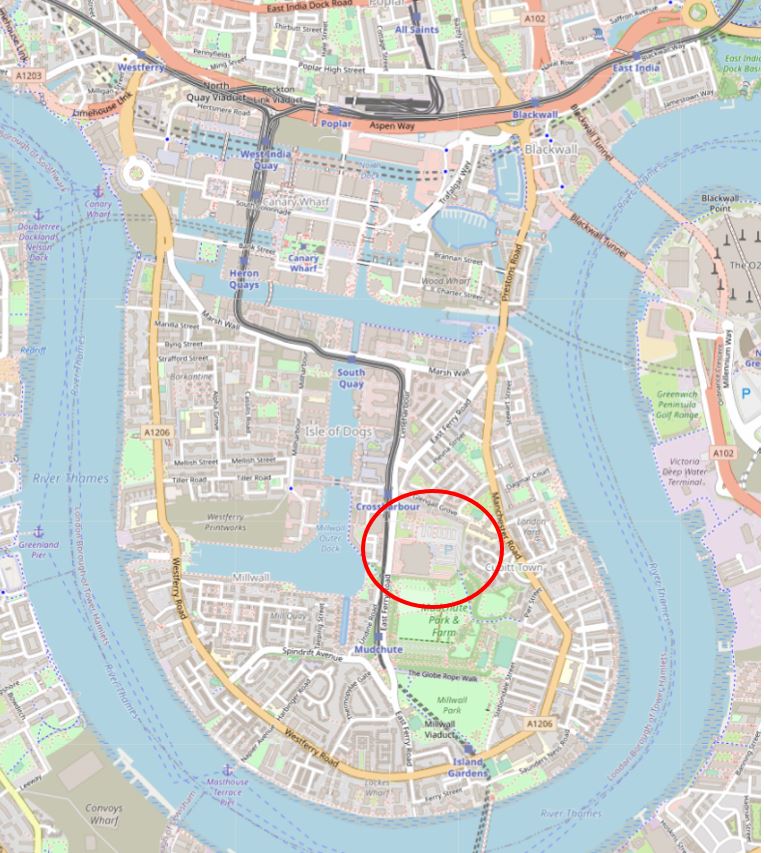

My father took the photo at the top of the post, and did not leave a record of the location. I do vaguely remember walking past the wall in the mid-1980s and that it was somewhere near the Poplar High Street end of Prestons Road, somewhere around the location highlighted by the red oval on the following map (© OpenStreetMap contributors):

I think I found the location when I went for a walk along Prestons Road, and I will explain later in the post, however before walking the road, some background to a road that has changed significantly in the last decades.

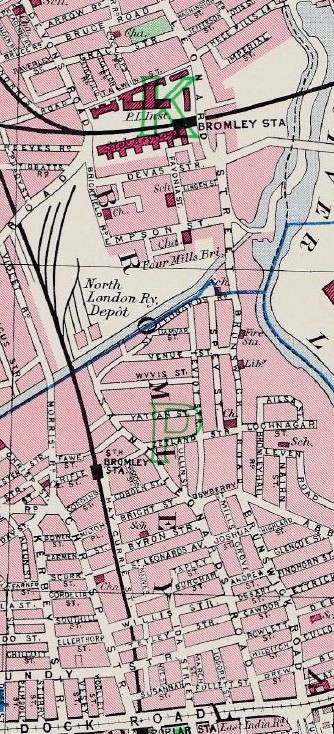

The most significant change to Prestons Road is in the northern part, up to the junction with Poplar High Street. Between the northern and southern sections of the road, it has been divided by a large roundabout and the dual carriageways of the A1261, or the Aspen Way, which is carried over the roundabout, as can be seen in the above map.

The A1261 provides a route between the A13 at the start of the East India Dock Road in the west, through to the Lower Lea Crossing in the east.

Construction of this road had significant impact on the area, and in some ways, reinforced the division between the Isle of Dogs and the rest of Poplar. The A1261 was built as part of the transformation of transport infrastructure surrounding development of the Docklands, which included other major projects such as the Limehouse Link Tunnel.

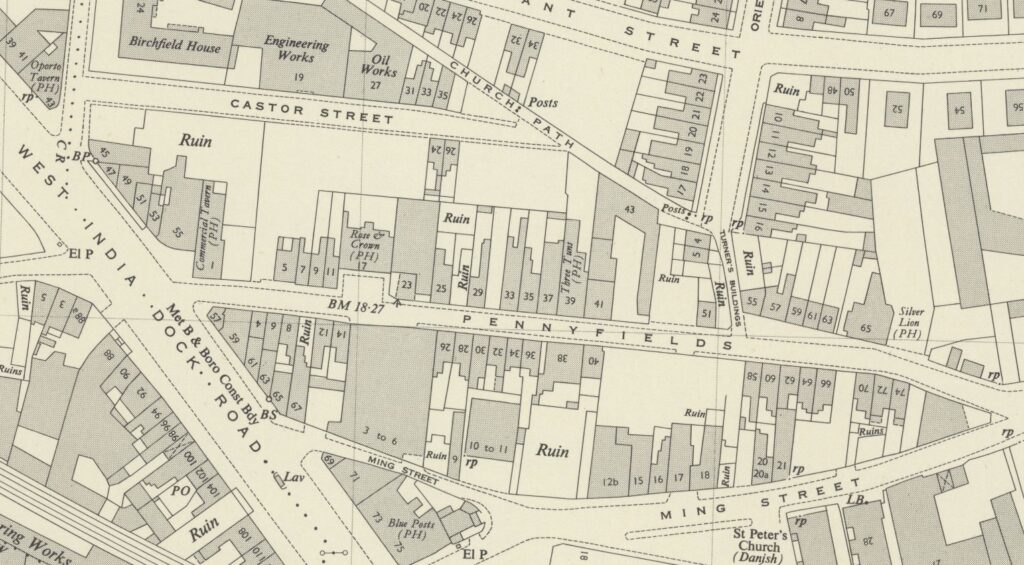

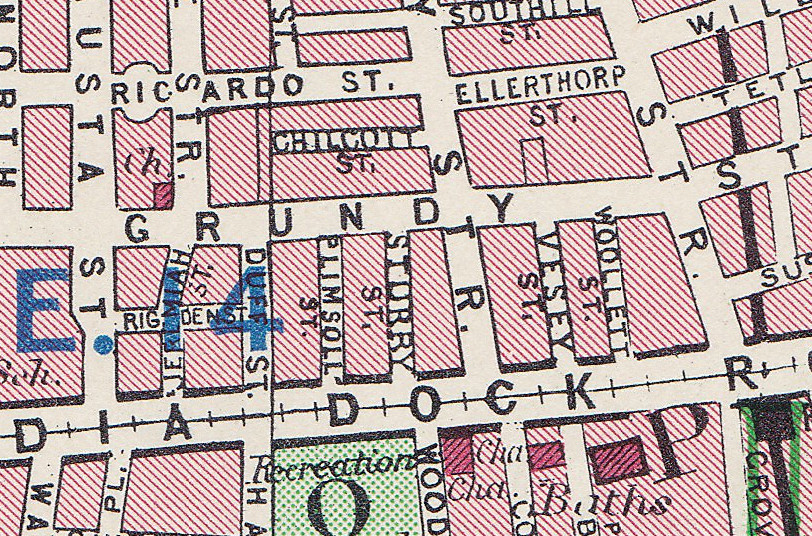

To illustrate the impact of this road, and the roundabout, the following map is from the 1950 edition of the Ordnance Survey, which covers roughly the same area as in the above map. The location of the roundabout is shown by the red circle (‘Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland“):

By comparing the two maps, it can be seen that the northern part of Prestons Road, up to Poplar High Street has changed to enable the entry and exit carriageways to the roundabout. Where Prestons Road once had a straight section down from Poplar High Street, it is now more angled to accommodate the roundabout. This will be relevant when searching for the location of the graffiti.

Taking a wider view of the area, we can see the Aspen Way running left to right at the very north of the Isle of Dogs. Just to the south, Billingsgate Market, and the office blocks around North Quay and the northern section of Canary Wharf reinforce the boundary created by the Aspen Way, leaving two main routes to the Isle of Dogs on the east and west of the peninsula – the eastern route being Prestons Road (© OpenStreetMap contributors).

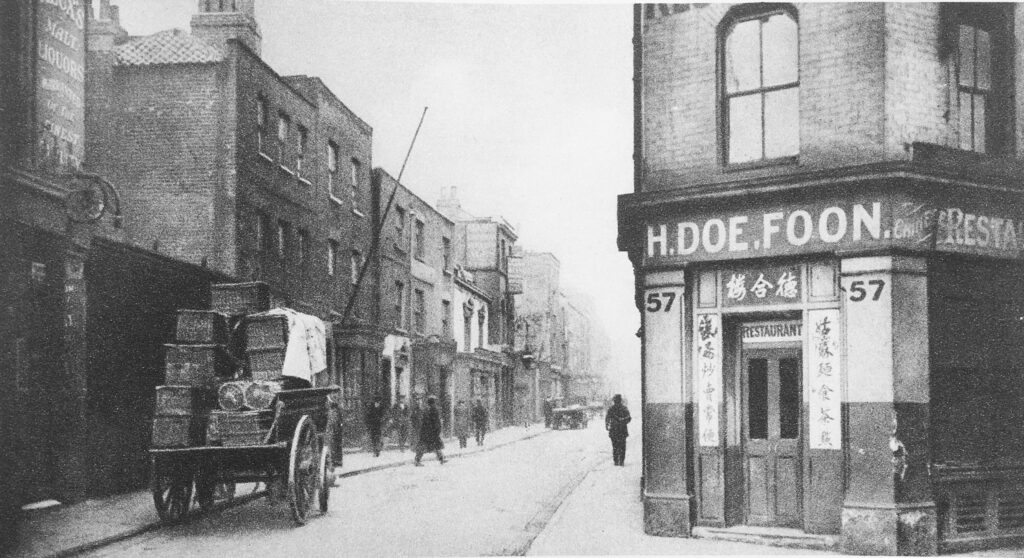

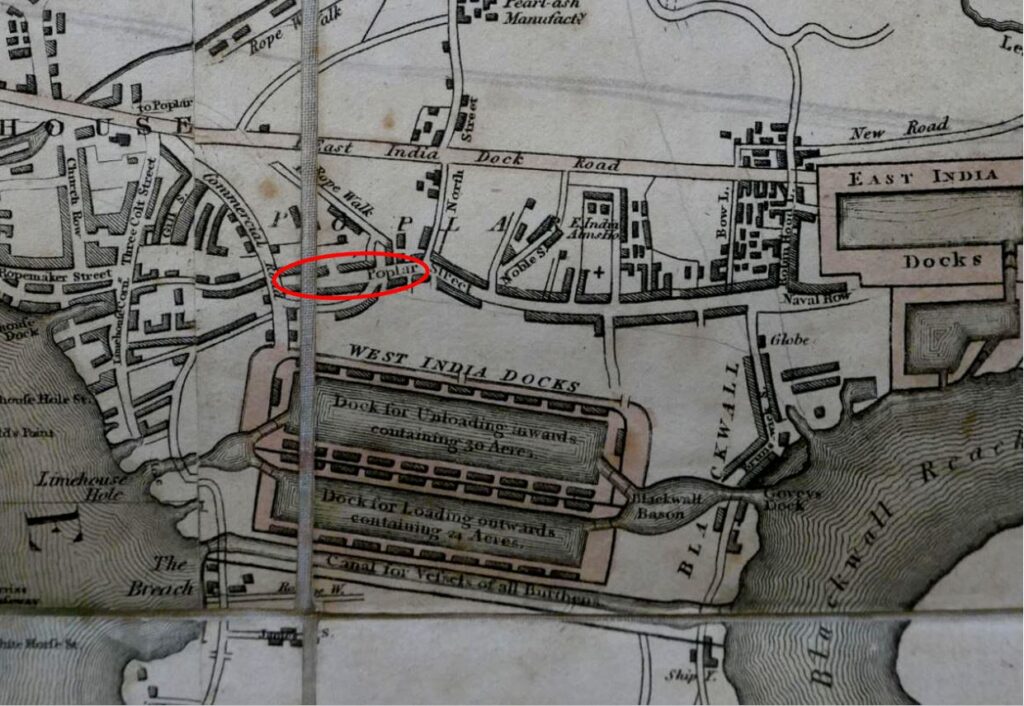

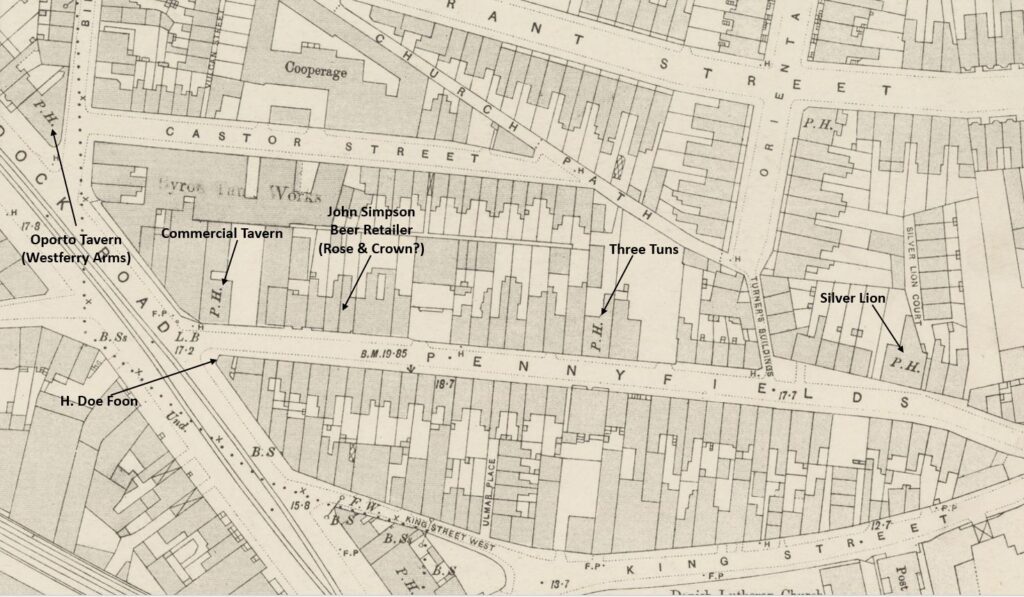

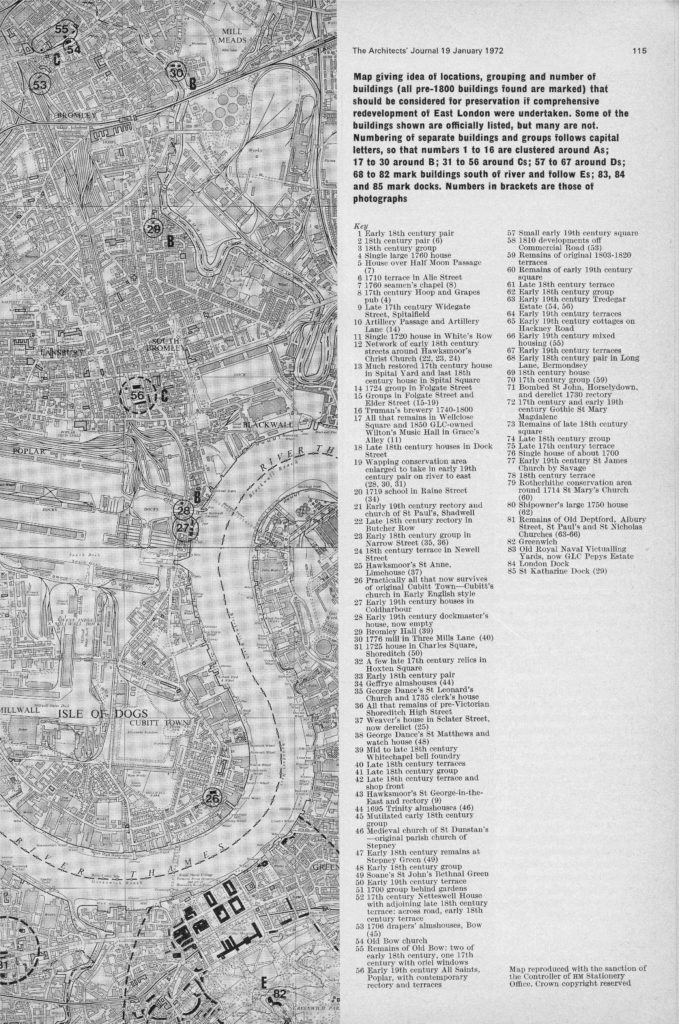

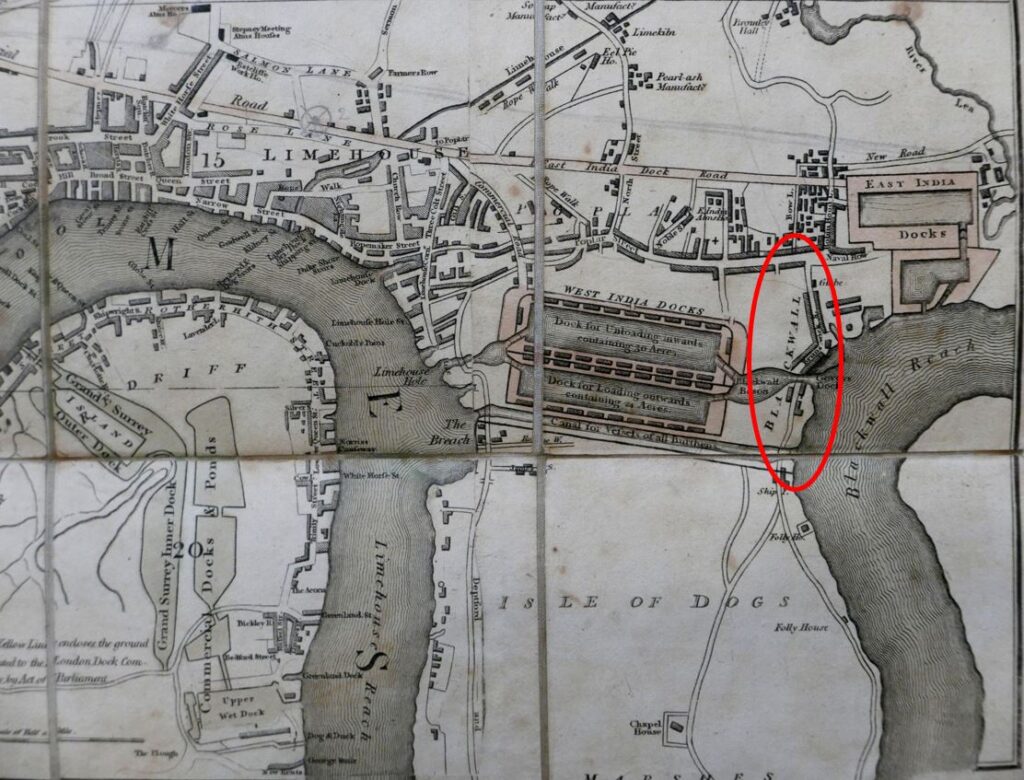

This boundary between the Isle of Dogs and Poplar has been long in the making. The following extract from Smith’s New Plan of London, dated 1816, shows that the construction of the West India Docks had created a barrier across the centre, leaving only the two roads either side of the peninsula:

In the above map, I have circled the location of Prestons Road, and whilst the southern section across the dock entrances was in place, the northern section had not been built. Instead, a turn to the right entered Brunswick Street.

I believe that the northern section of Prestons Road was built at the same time as the Poplar Docks which were located on the left of the section of the street just to the south of the roundabout.

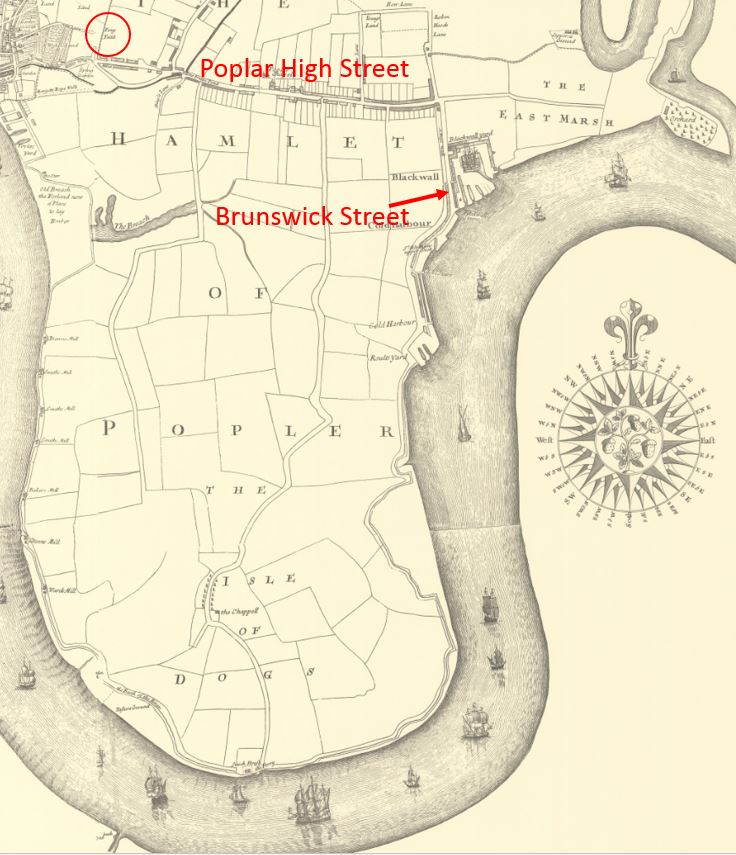

We must go back to the 18th century, to see the area before any of the docks were built to understand how the docks, and then Canary Wharf and the Aspen Way have created an apparent northern boundary to the Isle of Dogs.

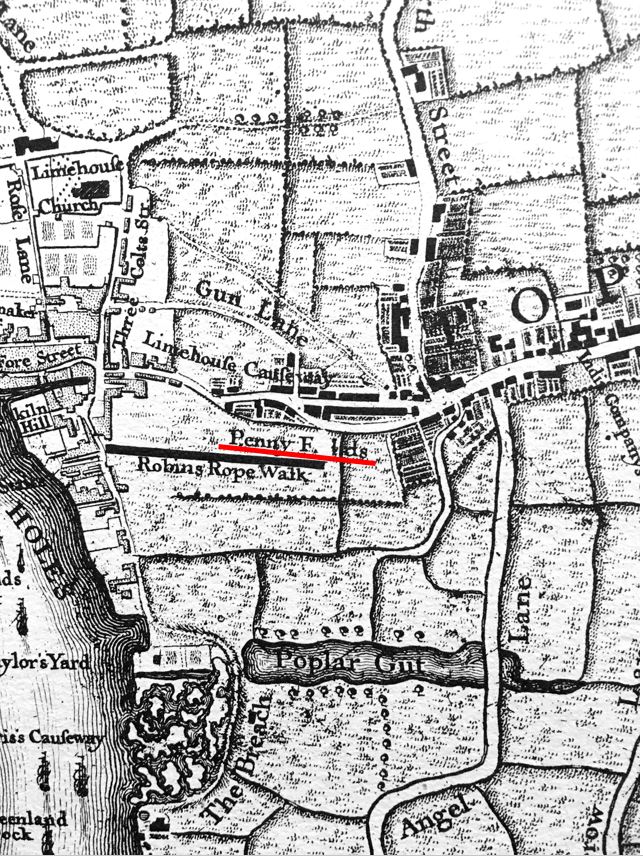

In the following map from 1703, we can see that the whole area was part of Poplar, with Poplar High Street already lined with buildings. To follow on from last week’s post, I have also circled a reference to Penny Fields to the left.

Brunswick Street is to the right, however rather than just east and west routes, up until the construction of the docks, there were to roads running down from Poplar High Street, including the central road which ran down to the ferry across the Thames to Greenwich, at the southern tip of the peninsula.

So today, when crossing under the Aspen Way, it feels like a boundary has been crossed, and we are entering the Isle of Dogs. Time to take a walk along Prestons Road:

The above photo was taken at the junction of Prestons Road with Poplar High Street.

For this post, I am using the spelling of the street as seen on the street name signs in 1986 and today. Many references to the street also refer to Preston’s, however to stay with the name signs, I will leave out the apostrophe.

The following photo is looking south from the junction in the above photo. The upper part of Prestons Road was angled slightly to the left when the roundabout was built. If I remember rightly, the wall with the graffiti was somewhere along the right side of the street.

A short distance down the street is a turn off to the right with Poplar Business Park at the end:

In the background of the 1986 photo, the frame of a building under construction can be seen. The majority of buildings to the south of Poplar High Street are relatively recent, and do not date back to the 1980s, however I wondered if the Poplar Business Park could be the building which was under construction when my father took the photo.

It is certainly in the right place, if my memory is correct that the wall was around here.

I looked for references to the Poplar Business Park to try and date the building, and found an advert from 1988 for “Moat Security Doors, Poplar Business Park, Prestons Road, Isle of Dogs, E14”, who sold iron gates to add security in front of a door, or as they advertised “Never be afraid to open your front door again”.

So the Poplar Business Park was in operation in 1988, so possibly safe to assume it was the building photographed under construction two years earlier. Interesting that whilst in the Poplar Business Park, they used Isle of Dogs in the address, despite being at the northern end of Prestons Road, very close to Poplar High Street.

If I am correct, the wall would have been to the left of the above photo, or perhaps to the left of the photo below which is looking up Prestons Road, with the side road to the Poplar Business Park being the street where the grey car is about to exit:

A very short distance to the south is where Prestons Road crosses under the A1261, the Aspen Way, a very significant set of new road infrastructure:

From the south, looking north, and the slip road to the east, up to the Aspen Way towards the City of London and one of the new road access points to Canary Wharf:

From the edge of the roundabout we can see some of the new residential towers that are becoming so common across this part of east London:

A full view of the routes that can be accessed via the roundabout that obliterated part of Prestons Road:

This is the view looking south along Prestons Road into the Isle of Dogs. I do not live there, so I am not really one to judge, but when walking the area, it is only along here that I feel I am entering the Isle of Dogs:

In the above photo, there is a tall brick wall, in shadow, on the right. This is the wall between the street and Poplar Docks, the construction of which I believe, resulted in the construction of this section of Prestons Road, as a road would have been needed along the boundary to serve entrances to the docks.

The following photo is of Poplar Dock today, looking west with two cranes remaining from when the dock was operational:

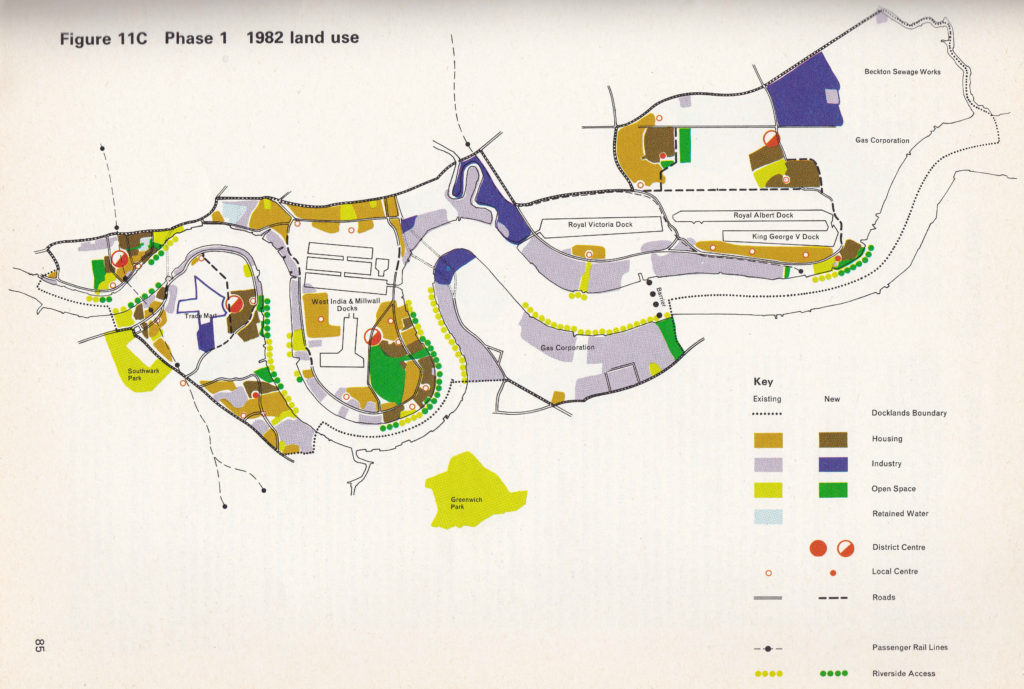

The site is now Poplar Dock Marina and is full with narrow boats and an assorted range of other smaller craft. Poplar Dock opened in 1851, however the site had originally been used from 1827 as a reservoir to balance water levels in the main West India Dock just to the west. In the 1840s the area was used as a timber pond before conversion to a dock.

Poplar Docks served a specific purpose, being known as a railway dock as the docks were almost fully ringed by railway tracks and depots of the railway companies.

Walking south along the street, and the area between the street and the river is full of new buildings, however there is a rather strange, flying saucer shaped building to be seen:

The building is one of the air vents and access points to the Blackwall Tunnel, which runs parallel (but deeper) to the northern section of Prestons Road.

Looking north towards the roundabout, and we can see the tall brick wall that once separated Poplar Dock from Prestons Road:

We now come to one of the crossings over the channels from the docks to the Thames:

This is the channel that ran from the Thames to Blackwall Basin, and then led into the West India Docks (see the extract from Smith’s New Plan of London, dated 1816 earlier in the post).

This is the view looking east along the channel towards the Blackwall Basin. The Canary Wharf complex has been built over much of the old West India Docks.

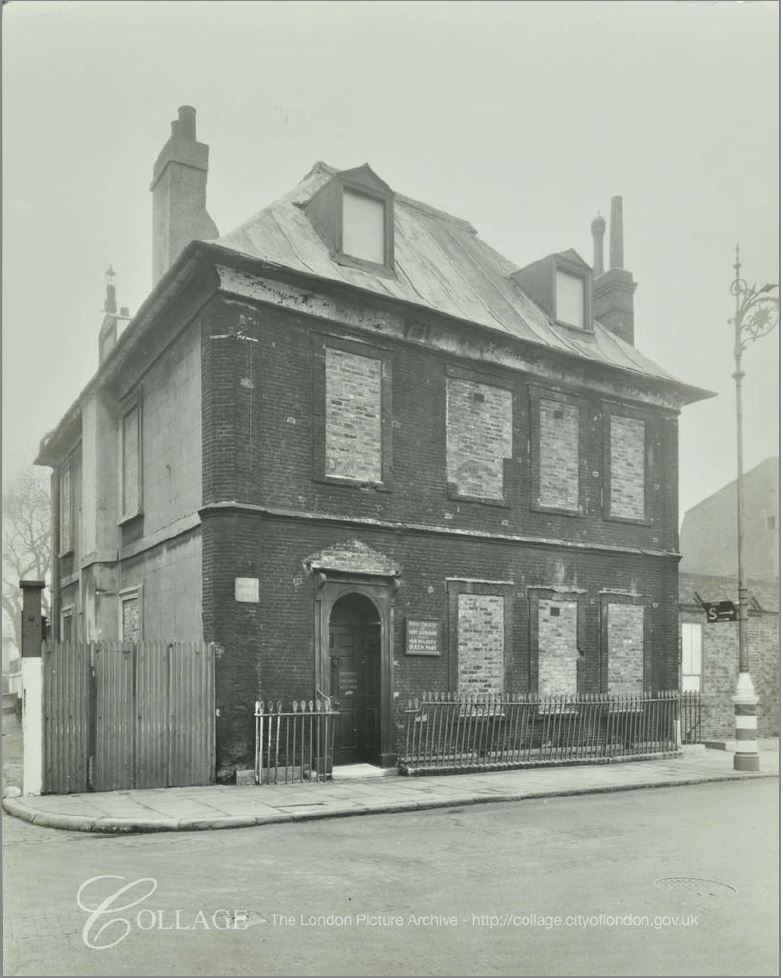

To the right of the above photo, behind the trees is the old Dockmaster’s House:

The Dockmaster’s House is named Bridge House and was built between 1819 and 1820 for the West India Dock Company’s Principal Dockmaster. The entrance to the house faces to the channel running between docks and river, however if you look on the right of the building, you will see large bay windows facing out towards the river. This was a deliberate part of the design by John Rennie as these windows, along with the house being on raised ground would provide a perfect view towards the river and the shipping about to enter or leave the docks.

A short distance further on and Prestons Road crosses another channel between docks and river. This is the channel between the West India South Dock and the Thames, and the view west provides a stunning view of some of the recent developments:

With the Docklands Light Railway crossing the old dock in the distance:

Original cranes remaining from when this was a working dock:

It is fascinating when standing here to imagine the many thousands of ships that have entered or exited through this channel, and where they had been coming from or going to.

Looking east where the channel meets the river.

The bridge that spans the channel in the above photos is the bridge that has taken on the name of the Blue Bridge.

Built during the late 1960s, the bridge is just the latest of a number that have spanned the channel.

I have never seen the bridge lift, but I was lucky enough to go under the bridge during a trip along the Thames on the Massey Shaw fireboat back in 2015:

The bridge marks the end of Prestons Road, continuing south, the road changes name to Manchester Road, all the way to the southern tip of the Isle of Dogs, where the road again changes name to Westferry Road, which then continues along the western side of the Isle of Dogs, all the way up to the West India Dock Road, which it joins opposite Pennyfields, explored in last week’s post.

The view heading south from the bridge:

On the right of the above photo, there is a row of terrace houses that run along a street slightly offset from what is now Manchester Road. This terrace marks the original route of Manchester Road up to an earlier incarnation of the bridge.

Having come to the end of my walk along Prestons Road, there was one last place I wanted to find.

Asda was part of the graffiti on the 1980s wall, so I wanted to find the store that would change the approach to shopping on the Isle of Dogs.

I have marked the location of the Asda store, with its surrounding car park on the following map (© OpenStreetMap contributors):

I walked along Manchester Road, then cut through Mudchute Park:

As usual, there is far too much for a weekly post, and I will return to the Isle of Dogs and places like Mudchute in future posts, however it was an area of land created by dumping the spoil when constructing and dredging Millwall Dock.

Now a large area of parkland, a city farm, and with a restored anti-aircraft gun, commemorating the Second World War when a number of these guns were based in the area, and the terrible suffering from bombing of those living on the Isle of Dogs:

An exit from Mudchute runs directly into the Asda car park, with the many new developments gradually taking over the Isle of Dogs in the background:

This was the change in shopping in the 1980s when many of the major stores opened up large “superstores” with car parks where you could drive and do a complete weekly shop without having to go to a number of separate shops.

Perhaps more convenient, but an approach that would result in the closure of so many individual, often family run shops.

The view across the car park to the Asda store:

The store gives away its 1980s heritage by the lack of lots of glass, which is typical of the majority of recent stores of this type.

The coming of Asda marked the early years of the developments that would dramatically change the Isle of Dogs, change that is continuing as the glass and steel towers continue to grow.

It would be great to know if I have the correct location for the wall with the graffiti.

If any past or current resident of the Isle of Dogs can confirm, or advise the correct location, I would be very grateful.

I assume the wall was just demolished as part of the development of the area, and the changes as a result of the new roundabout and the Aspen Way. A real shame that the wall was not kept, as part of the historical records of the changes to this fascinating part of London.